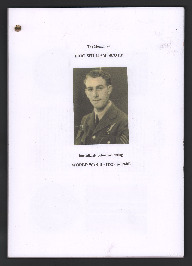

The memoir of Eric William Scott

Title

The memoir of Eric William Scott

Description

Text and numerous b/w photographs (some of which are also located in sub-collection albums) covering from immediately before and during World War II - (1939-1946). First page has colour photographs and description of prisoner of war medal. Continues with account of RAFVR training including time at the Air Crew Reception Centre, St John's Wood, London, initial training at Stratford-upon-Avon and elementary flying training at RAF Watchfield. Gives account of journey to the United States to continue training on the Arnold Scheme at Turner Field, Albany, Georgia, Callstrom Field, Arcadia Florida, Gunter Field, Montgomery Alabama and Craig Field, Selma, Alabama flying Stearman, BT-13 and Harvard. At the last location an accident brought an end to his pilot training and he continues as navigator/bomb aimer at Picton in Ontario Canada. Pages contain many photographs, exttracts from the cadet handbook and his logbook. On return to UK he did operational training a RAF Moreton in the Marsh where he crewed up. He got married just before posting to North Africa. Gives account of journey to join 205 Group in North Africa and of first tour on 142 Squadron where he flew 38 operations and of life in North Africa. After this he was posted as an instructor to an operational training unit in Qastina Palestine where he had an opportunity to visit Jerusalem, Haifa, Bethlehem and Tel Aviv. In June 1944 he agreed to do a second tour and was posted to 37 Squadron at Foggia in Italy. Gives account of operations including gardening in the Danube river. Gives account of final operation to Maribor marshalling yard in Yugoslavia where after attack by night fighter he baled out of his aircraft. Follows with account of capture by Croatian military. hand over to the Germans and journey to Stalag Luft 7, Upper Silesia and life in prisoner of war camp. Then underwent the long march back to Germany in the face of Russian advance. Concludes with repatriation and life after return to England.

Creator

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Coverage

Language

Format

Thirty-seven page printed document with text and photographs

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

BScottEWScottEWv1

Transcription

The Memoir of

ERIC WILLIAM SCOTT

[Photograph]

Immediately before and during

WORLD WAR II – (1939 to 1946)

[Page break]

ALLIED

EX-PRISONER OF WAR

MEDAL

[Photograph]

Obverse: The prominent feature of the front or obverse side of the medal is the strand of barbed wire which has entrapped a young bird, symbolic of freedom itself. These elements surmount a globe of the world indicative of the international parameters of the medal. The wording “International Prisoners of War” encircles the entire design.

Reverse: The haunting and vicious barb of the ever present wire is used symbolically to divide the reverse side of the medal into four elements, each bearing one of the words in the phrase “Intrepid against all adversity”.

Ribbon: One of the most distinctive medal ribbons yet designed, it is woven 32mm wide with an unusual feature in having a symbolised strand of white barbed wire 2mm wide placed centrally, this is bounded on either side by 4mm black bands representing the despair of the compound. These, in turn, are edged by two further white 2mm bands representative of the second and third fences of the compound, outside of these are 7mm bands of green, reminiscent of the fields of home and finally, both edges are comprised 2mm red bands symbolic of the burning faith of those who were interned.

[Photograph]

[Page break]

FOREWORD:

From the age of 14 1/2 years old – 1936 – I was employed by Clayton Dewandre Co. Ltd., of Lincoln. Initially my work included machine shop and fitting practices. During the latter part of 1938 I was accepted as a student apprentice and commenced work in the Research and Development Department as a student Technician. I attended evening college, on Monks Road, Lincoln, four nights each week studying for an ONC in Engineering.

When war was declared in September 1939 I was concentrating on the development of a twin piston air compressor, to provide air pressure for a new tank being developed at the Ministry of Defence at Chobham. I was involved in other projects too; new air/oil coolers for the Spitfire and Hurricane, power assisted controls for the same aircraft, radiators/coolers for army vehicles and tanks and new braking systems for vehicles and gun limbers.

In January 1941, having successfully completed my ONC Engineering Course, I decided that I would volunteer for the R.A.F. Because of my reserved occupation my only option was to try and be accepted for aircrew duties, which is what I wanted and would prevent Clayton Dewandre from blocking my acceptance.

R.A.F.V.R. TRAINING

I arrived at the RAF recruiting office in Saltergate, Lincoln, in February 1941. The necessary forms were completed, I was almost 19 years old at the time. Notification was received in March from the RAF to attend Cardington, Bedfordshire, for written, oral and medical examinations over a three-day period. These examinations did not prove difficult except for one oral question of “what route would I take if I flew from England to Turkey, without crossing belligerent countries?” My geography was never a strong point and I had to admit to the four officers of the board that I didn’t know.

However, I was accepted into the RAFVR as a Pilot under training (U/T Pilot) and sworn in along with approx. 50% of those attending at the time. My RAF number was 1425752 and a silver lapel badge showing RAFVR letters, with an eagle, was issued to each person.

The officer in charge of the intake of applicants explained that they had too many aspiring aircrew at the time, and because of the limited training facilities, we would now be on deferred service until notified. I returned to Clayton Dewandre and continued with development projects until call-up papers were received in August 1941. These instructed me to report to St. John’s Wood, London, adjacent to London Zoo! It was always known as A.C.R.C. (Air Crew Reception Centre).

[Page break]

[Photograph]

AIRCREW RECEPTION CENTRE

12/7 FLIGHT – LONDON – AUGUST 11TH 1941

[Page break]

We were billeted in large flats – six bunks to a room. I was “closeted” with five Scotsmen and for some days just couldn’t understand a word they were saying. What with shedding ones hair and other “foreign” phrases it was very difficult to communicate. However, they became very staunch friends during our initial training.

During our three weeks at A.C.R.C. we were re-examined medically, given all the necessary injections, inoculations, blood tests, etc., including a smallpox vaccination. Many of the recruits suffered quite a lot of pain from this intensive treatment, particularly from the vaccination. I was fortunate since, having been treated as a child, my reaction was minimal.

“Kitting out” was a major operation – large kit bag stuffed with spare boots, best blues, vest – airmen for the use of – underpants, numerous pairs of socks, four shirts with eight loose collars, two ties, two side caps, shoe cleaning brushes, button cleaning equipment, sewing wallet, gas masks and tin hat. We had to remove our civilian gear to the Wembley Warehouse and don our battledress equipment. Each side hat came complete with a detachable white flash which fitted around the front and was held in place by one of the turned-up peaks. This indicated that the wearer was aircrew under training. Whilst at the warehouse in Wembley we were instructed to pack our civilian attire and wrap it in brown paper, with the address clearly printed on the label provided. These were then dealt with by the RAF stores personnel.

Whilst at the A.C.R.C. we were divided into Flights of approximately fifty recruits and were drilled, drilled and drilled – every day – to “lick us into shape”.

Being a short person i.e. 5ft 6” I was always halfway down the flight rank. Those at the front and the rear were mainly ex-policemen. It meant that we shorties had to almost run to keep up with those in front and, to prevent those at the rear from treading on our heels. The corporal in charge eventually got the stride distance sorted out – R.A.F. Standard - which suited all concerned.

3

[Page break]

STRATFORD ON AVON

INTIAL TRAINING WING

[Photograph]

[Photograph]

PROMOTION TO L.A.C. NOVEMBER 3RD 1941

[Postcard]

[Page break]

INITIAL TRAINING WING, STRATFORD-ON-AVON :

AUGUST 1941 – NOVEMBER 1941

We were billeted in hotels commandeered by the MOD. I was in the Falcon Hotel – a very old building with sloping floors, small windows and creaking stairs and floorboards. Whilst at Stratford we had to do guard duty – two hours on – four off – from 6.0 pm to 6.0 am. During the winter months it was not very pleasant and the creaking/groaning of the swinging hotel signs were, initially, rather daunting particularly when coupled with the church clock chiming and listening for the officer and NCO of the guard watch coming round to try and catch us out.

During our stay at Stratford we were taught Morse code both sending and receiving, including Aldis lamps, navigation and the Dead Reckon Type with Mercators charts, maths, aircraft recognition, theory of flight, aero engine design and, of course, drilling!

Our working day commenced with reveille at 6.0am and breakfast at 7-7.30am and ended at 4.30pm (16.30 hours). Wednesday afternoon was for sport which I spent rowing on the Avon. I also had the opportunity of seeing a few shows at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre.

We sat our exams at the end of October 1941 and I was promoted from AC2 (the lowest Non-commissioned rank to LAC – (Leading Aircraftsman) on the 3rd November 1941. This entailed sewing a cloth badge showing an aircraft propellor onto the sleeves of our uniforms. Pay also increased from two shillings and sixpence per day to five shillings per day. I was suddenly rich beyond my wildest dreams.

FLYING TRAINING

The way was now open to commence flying training. Prior to going home on my first leave, we were issued with an additional kit bag containing an inner and outer flying suit – special flying socks, flying boots, silk, wool and gauntlet gloves and flying helmet with goggles. Taking all this gear home was quite a problem, the total kit comprising one large kit bag, one flying kit bag, upper and lower pack, side pouches, gas mask and tin hat.

One week after completing I.T. Wing training I was posted direct to RAF Watchfield, No. 3 E.F.T.S. The airfield was all grass and was mainly a beam approach training school flying Oxfords and Ansons. Supplementary to this was an Elementary Flying Training School with Tiger Moths and Biplanes made by DeHaviland [sic, and this was my destination. The weather that November was very cold and a few minutes in the air, with the open cockpit aircraft, froze our faces. The bulky fling suits were a necessity and the boots, lined with sheepskin, did manage to keep the circulation going in the feet.

My fling instructor was Lt. Bembridge, a Battle of Britain Pilot. He was very anxious to show me the aerobatic qualities of the Tiger Moth. Often, after landing, my face would be ashen and I felt very sick but I was never actually air sick. The

4

[Page break]

WATCHFIELD, NR SWINDON

[Postcard]

GYPSY 7 ENGINE – 200 H.P. MAXIMUM SPEED – 120 MPH

NOVEMBER 21ST – DECEMBER 1ST

Total hours flying 6 3/4 in which time

I passed out Solo

[Page break]

aircraft was very good to fly being light and responsive to control changes. It was, however, quite difficult to land because of its lightness and we rookies often found ourselves trying to “put the wheels down” whilst we were still ten feet or more above ground level. This, with the subsequent bouncing, was known as “walking it in”. Undercarriage repairs were required every day, but on completing the required flying exercises – see pilot’s log book – and after 6 hrs 10mins dual instruction I was allowed to go solo. It was a tremendous feeling and quite frightening to know that I was on my own and a safe take off and landing was my responsibility. There were other RAF men on the ground watching my progress and biting their nails. I cannot remember exactly but I think I completed three take offs and landings during the 00.35 minutes solo.

The time at No. 3 E.F.T.S. Watchfield was apparently an elimination period. Those who had gone solo, 8 hours allowed, were detained to go for further training to either Canada, America, South Africa, Rhodesia, or Australia on what was known as the Empire Air Training Scheme. Those cadets who needed a little extra flying training, but showed promise, were posted to other E.F.T.S. schools in the UK whilst the remainder had to re-muster as navigators, wireless operators or air gunners.

The Empire Air Training Scheme was initiated because of enemy action and weather conditions severely limiting flying training courses in the UK therefore preventing the flow of trained aircrew, with operational service, at the rate required.

Generally, the country providing the training paid for new airfields to be built and a large proportion of the training costs. This included the U.S.A.

THE ARNOLD SCHEME – UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Following a brief period of leave from Watchfield in December 1941, I was instructed to report to Heaton Park, Manchester. The weather was atrocious with rain and fog. Approximately 3,000 cadets congregated at that venue and we had to “hang around” until our names and numbers were called when we went to a billeting clerk to be told who we were to stay with and the address.

John Player and myself were given the same billet – a Mrs. Pimlett – the address escapes my memory. On arrival we were met by a middle-aged lady in best “bib and tucker”, complete with carnation. She welcomed us into her home, showed us our room and explained that she was going to a wedding. She then invited us to go to the evening reception and wrote down the address.

After a bath and general “tidy up” and, with best blues donned, buttons shining and boots polished, John and I went to the address given.

We were truly welcomed by the wedding party and enjoyed the evening with them, eventually returning home with Mrs. Pimlott.

We learned that our landlady had an invalid husband and she financed their living by taking in sewing of pre-cut garments and of course now by providing a billet for such

5

[Page break]

[Photograph]

Mid-Atlantic on board the ‘Montcalm’

12th January 1942

[Photograph]

Our only company across the Atlantic the ‘Volendam’

[Photograph]

Moncton Railway Station

Canada

[Page break]

as John and I. The sewing side was almost slave labour and she had to work all day and well into the evening to obtain a meagre income.

John and I departed Manchester for Glasgow on January 6th and embarked on the S.S. Montcalm. This ship had been an armed merchantman before being converted into a troop ship. A 4” naval gun was mounted at the stern and this ship was, we were told, of 13,000 ton capacity. We set sail on January 8th 1942 with a sister ship names Volendam which also had RAF cadets on board, and in convoy with other ships and destroyer escorts. After leaving Glasgow we called at Milford Haven and then nosed out into the Atlantic. The weather, after two days at sea, became very stormy and the ship pitched and rolled to an uncomfortable degree. Many men were sea sick and food was definitely out of order. John and I lived on arrowroot biscuits and lemonade for eight of the fourteen day voyage to Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada.

During the very story crossing we were called upon to carry out various duties and mine was submarine watch! I couldn’t have recognised a periscope if I had seen one and in any event, the waves and ship movement were such that just staying upright was enough without looking for submarines.

Although I had been allocated a hammock for sleeping purposes, I just could not get into one, and kept falling out the opposite side so swapped for a bunk – even though the ship’s movement was intensified by a fixed bunk.

Because of the atrocious weather conditions our destroyer and convoy of ships disappeared after five days out into the Atlantic. The Volendrum went out of sight after a further two days sailing.

Eleven days after leaving Glasgow the bad weather gradually abated and we started eating Navy food again on the mess deck, but it was necessary to hang on to the plates to prevent them sliding off the end of the table.

After thirteen days at sea we were thrilled to see the bright lights of Moncton appear on the horizon.

The first things I saw after docking were large stalks of bananas – my favourite fruit – which I had not seen since 1939/40. I bought a complete stalk and shared them with John – they were delicious.

The temperature in Moncton was well below zero and a good covering of snow was evident. The cold could easily cause frost bite but it was a dry cold and providing that we were well covered, including ear flaps, a good walk would generate a pleasant glow.

The barrack blocks were well above RAF standards as also was the food.

We were at Moncton for only a few days whilst the “powers that be” allocated the 3,000 cadets from the Montcalm to the various training establishments in the U.S.A. and Canada.

6

[Page break]

[Photograph]

Canadian Prairies in January 1942

[Photograph]

Albany, Georgia, USA

Looking down Main Street – January 1942

[Photograph]

Our barrack hut – No 5 – 9th Feb 1942

[Photograph]

British Cadets marching back from Retreat Turner Field, Albany

[Photograph]

Right

Our black waiters at Turner Field Albany, Georgia

[Page break]

Our train journey commenced late January – destination: Turner Field, Albany, Georgia, USA, and lasted for five days. We slept in bunks which hinged down from above the windows. The Canadian prairies and Northern States of the USA were thick with snow – see photographs.

The train stopped for a short time at Grand Central Station, New York and also at the AMTRAC main station of Washington DC. We travelled south through Virginia, North and South Carolina and Georgia and the weather became warm and pleasant.

TURNER FIELD, ALBANY, GEORGIA

Our stay at Turner Field was only for approximately two weeks during which time we were introduced to the American Army Air Corp disciplines and daily routines.

We were housed in two-storey barrack huts – see photographs – each room housed two cadets and the standard of comfort was very good. The base had its own band and this marched round the camp at 06.30 hours at Reveille, at which time we had to don our shorts and ‘T’ shirts for thirty minutes of P.E., always starting and finishing with press-ups. With this rigorous daily routine we quickly regained our fitness. Each cadet was weighed by a dietician and allocated a “weight” table in the dining room and, by that means, the calorie intake was controlled. I was on an underweight table, weighing in at just eight stone. This table had lots of rich foods and unlimited bottles of milk. Needless to say, my weight remained the same but I did justice to the food!

During our visits to the dining room we were instructed that we must only sit on the first two inches of the chair. Why this stupid rule existed I do not know, also our backs had to be upright at all times, i.e. sat to attention. At 18.00 hours we were marched to the parade ground for the last post and lowering the Stars and Stripes, at which time we had to sing the American National Anthem.

CARLSTROM FIELD, ARCARDIA, FLORIDA

Our stay at Turner Field ended with the transfer of John Player, Stan Gage and myself, along with approximately thirty American and British Cadets, in total, to Carlstrom Field, Arcadia, Florida. Arcadia was only a few miles from Sarasota and Fort Myers. Miami was approximately 200 miles further south.

Carlstrom Field had been a civilian pilot training base operated by Sembery Riddle Co. All staff were civilians except those responsible for discipline and routine flying checks. The civilians were taught on Piper Cubs whereas service personnel were trained on the American Military Primary Trainer, the Boeing PT.17 Stearman. This aircraft, although a biplane, could not be compared with the Tiger Moth. It was much heavier, more powerful, had a Wright Cyclone radial engine and, to our horror, had wheel brakes, the control of these brakes were by treadles attached to the rudder bars. This resulted in numerous ground loops with Cadets landing the aircraft in a tense condition and, inadvertently pressing down on one or more of the rudder bar brake treadles. Consequently, the maintenance staff were kept very busy repairing damaged wings.

7

[Page break]

[Picture]

[Page break]

ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE CADET’S HANDBOOK

LATERAL CONTROL

Ailerons – The ailerons, which are the surfaces used for lateral control of the airplane (wing down or up) are situated on the outer, trailing edge of the wing and are used for rolling the airplane ….

[Pictures]

LONGITUDINAL CONTROL

The Elevators – are horizontal, movable control surfaces located, on conventional aircraft, on the tail group, controlled by forward or back pressure on the stick and are used for obtaining longitudinal control (up and down).

[Pictures]

NB: Handbook still complete and in good condition

[Page break]

FRONT COVER FROM CADET’S HANDBOOK

[Picture]

[Picture]

CARLSTROM FIELD – 1941

Compared with the photo to the left, Carlstrom Field – 1941, as pictured above, may with all conservatism, be termed the ideal training ground for fledgling pilots.

Constructed at a cost of over a million dollars, the new Carlstrom Field facilities offer the utmost in providing for the student pilot’s health of mind and body. Moreover, every piece of flight equipment is the finest available, insuring insofar as is humanly possible, the student’s rapid advancement as a steady, dependable pilot.

The instructors at RAI have been chosen with extreme care and trained at RAI’s Instructors’ Courses to the end that you may be taught to fly by an aviator who is one of the best in the game.

It is a matter of tradition and record, substantiated by the rosters of Military and Commercial aviation, that pilots trained at Carlstrom Field have gone forth as some of the most capable in aviation’s history.

[Page break]

My instructor was a Mr. R.L. Priest, a very patient man. We were all issued with a book which gave a detailed account of how to carry out various manoeuvres including aerobatics. I was allowed to fly solo on the 24th March 1942 – see Certificate in Cadets Handbook – after being checked by Mr. Jane. Further checks were made at 20, 40 and 60 hours, and if satisfactory the specified stages of the Primary Training were complete.

During our stay at Arcadia we were allowed off base – “open post” from 4.0pm Saturday until 10.0pm Sunday. After exploring Arcadia – only one day necessary – we ventured further afield to Sarasota and Fort Myers. Before being able to hire a car we had to obtain a licence from the local Sheriff which meant driving him round the block.

Eight of us shared one car. Those who had driven before and held British Licences went first and those, such as myself, hung back. However, after five cadets had taken the Sheriff round he said “Okay boys, let’s give you your licences”, so we all qualified.

John Player, Stan and I generally went into either Sarasota or Fort Myers during “Open Post” staying at the cheapest guest house we could find. Our pay was only five shillings, plus two shillings and six pence flying pay, plus six pence colonial allowance per day, i.e. eight shillings per day. The rate of exchange was 4.50 dollars to the pound. The American cadet pay was 10 dollars per day.

We met many good and generous hosts during our breaks from camp but we were amazed by the number of people (males) who wore Stetson and spurred boots, without a horse in sight!

Sarasota had a very large caravan trailer area, mainly used by Americans going south to escape the winter snows and cold weather in the north. The weather generally was very pleasant during our stay at Carlstrom but the extreme humidity made life rather uncomfortable and it was common practice to shower at least once during the night.

During our training, one of the flying exercises was pylon eighties which taught the cadet to allow for wind drift. This meant selecting a field and flying the aircraft with the wing tip held on one of the intersections, then flying diagonally across the field so the wing tip again intersected with the opposite corner of the rectangular field.

I am certain that almost all cadets were guilty of taking empty Coca Cola bottles up on this exercise and, choosing a field with cows, we would drop one after another of these bottles causing almost a stampede. The bottles gave a loud whistle during their descent. Many farmers waved their fists and tried to get our aircraft number on these occasions.

It was during my stay at Carlstrom that I heard the black staff – generally dining room and similar duties – join together after evening meal and last post, singing blues songs. They were very impressive and this practice among them was experienced by me at all of the other bases to which I was posted.

8

[Page break]

[Photograph]

The first batch of mail from home

Carlstrom Field, Florida

[Photograph]

Taken in the air, showing P.T. 17 flying above another aircraft – Carlstrom Field.

[Photograph]

Indian Children of Seminole Tribe, The Everglades, Florida

[Photograph]

Eric (left) & John – relaxing in Florida

[Photograph]

Home of the Stewart Family

[Photograph]

Dexter Ave. Montgomery

(Pop’s Car)

[Photograph]

Cameron Stewart at The Lake

[Page break]

Four day’s leave was granted at the end of our Primary Training. John and I decided to try and hitch to Miami. Our first lift, given by an insurance collector, took us a good 150 miles to Fort Lauderdale, calling in the Everglades at Indian settlements for their premiums. We met and spoke to the Seminole Tribe families and were permitted to take photographs of their children. A second lift took us into Miami where we checked in at a hotel. We didn’t expect to arrive in Miami on the same day as we left Arcadia.

During an evening meal we were approached by a middle-aged man from another table who enquired who we were and what we were doing in the USA. He asked us where we were staying and promptly said he would ring and cancel out room because we could stay in his hotel without any payment and this included all meals. He introduced us to his wife and friends and told us that he had emigrated to America after World War I and was from Sheffield. It was our good fortune to have been in the right place at the right time!

GUNTER FIELD, MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA

We returned to Arcadia after our leave to be posted to Gunter Field, Montgomery, Alabama for our Basic Flying Training.

Gunter Field was approximately six miles from Montgomery – the capital of Alabama and between the two was Kilby prison. During our first few weeks at the base it was noted that the electric lights dipped intermittently on quite a regular basis. We later learned that it was caused by the Electric Chair at the prison – very disconcerting to know that a prisoner was being executed when the voltage dropped.

Our aircraft for basic training was the BT.13 monoplane with fixed undercarriage. The exercises taught were virtually identical to those covered during Primary Training, except that we were not allowed to carry out snap rolls as they tended to twist the plane and fuselage. See Pilot’s log book for details of flying exercises. This part of our training concentrated more on instrument flying and cross-country daylight and night exercises.

My instructor was an ex-British Cadet from an earlier course, P/Officer Rogers. He was a good instructor and I enjoyed flying with him. Formation flying – three aircraft in ‘V’ formation could be somewhat traumatic at times, wing tips had to be placed and maintained between the wing and tail plane of the lead aircraft and not more than one wing length at the side. With air turbulence, particularly during afternoon flying, it was very dodgy. We also had to carry out low-level formation flying, as low as fifty feet. On one occasion, when flying along the Goosa River, the instructor in the lead aircraft was so low that water spray splattered us in the wing planes and a man who was fishing was so startled as we swept up the river, that he jumped in. Landing in formation was also very precarious. The lead aircraft pilot signalled by hand how many rotations of the main flap he was applying – we had to apply a higher number of rotations to ensure that we didn’t over-shoot him. On one occasion, I was rapidly rotating the flap handle when it came off its spindle. I had to make a rapid break from the formation. On another occasion an oil pipe in the engine nacelle fractured, spraying the windscreen and blocking all forward vision. Again it was a

9

[Page break]

[Photograph]

[Page break]

case of breaking formation and a hasty return to base, landing with only side vision! See large photographs of BT.13 – I am flying the nearest aircraft)

My Basic Training concluded on the 2nd July 1942. Durin my stay at Gunter Field, the first anniversary of Pearl Harbour was “celebrated”. The three American services decided to hold a parade in all major cities. The British contingent at Gunter were instructed by the O.C. RAF to take part. A Union Jack Flag was obtained and had to be paraded and escorted at the side of the Stars and Stripes. The first time they brought the British Flag onto the parade ground it was upside down. We were all issued with rifles – many months since we had carried out rifle drill, and even though it was July, with temperatures in the 90 degree F. region, we had to wear RAF Blue uniform. When we took these out of our kit bags the buttons were green and it took quite some time to bring them to parade ground condition.

Following the march through Montgomery, John and I made for the ice warehouse where we could buy a water melon to quench our thirst. It was at this point that an American youth came to us and suggested we should return home with him for lime drinks. He said his parents were across the road and they would drive us home. The youth was Cameron Stewart and his parents, Vannie and Pop. John and I went to the Stewart’s house and into the country on the Goosa river, almost every open post after that day. Very often Pop would pick us up to save us getting the bus into Montgomery. At that time Pop was co-owner of a gents outfitter’s shop. Their house was typical of those in the Southern States with Clapboard outer skin and very much like a plasterboard inner lining. All rooms were air conditioned and the freezer size, huge. All windows and door frames were wire netted to keep out the flies and mosquitoes.

The American hospitality was really rather marvellous, lines of cars would be parked outside the base on “open Post” and cadets were picked up at random and entertained by families for the weekend. Pop and Vannie’s hospitality continued when John and I were posted for Advanced Training to Craig Field, Selma, Alabama – a round trip of 100 miles from Montgomery – which Pop drove every weekend to pick us up.

This was the final stage to our graduation and the Advanced Trainer was the AT.6 Harvard, a high performance aircraft within the 200 mph bracket.

My instructor on this aircraft was P/O Percival and he allowed me to go solo after 2hrs.35 mins dual instruction. My stay at Craig Field was very short. During circuits and landings at an auxiliary airfield I was involved in an accident with another aircraft on the landing strip. The other aircraft was occupied by an American instructor who had disregarded all the ground rules for taxi-ing after landing and had decided to taxi to the take off point along the same route on which he had landed. I had chosen this line of approach to land and as the aircraft had already covered most of the landing length when I approached I did not see him reverse his tracks before I touched down. With a rear wheel it is not possible to see ahead after landing, until zigzagging when taxi-ing. Both aircraft collided.

Although there was a control aircraft on the airfield my instructor advised me that I wouldn’t receive any support from the American controller as he was a good friend of

10

[Page break]

EXTRACT FROM PILOT’S FLYING LOG BOOK

[Photograph]

[Page break]

[Photograph]

Telegram from mum on my 20th birthday – 10th March 1942

Also received telegrams from Jessie Brown, sister Dora Dickerson and sister Ethel Dixon (all telegrams still preserved in their original envelopes)

[Photograph]

PICTON, ONTARIO, CANADA

1942

[Photograph]

Approaching Canada’s Horseshoe Falls

[Page break]

[Photograph]

[Page break]

the instructor. Three American Officers checked my ability to fly the aircraft and at no time was my flying criticised. However, there had to be a scapegoat and that was me.

REMUSTERING – CANADA

On leaving Criag Field I was sent to Ottawa, Canada to appear before a board of officers who controlled the training of RAF cadets both in the USA and Canada.

During my interview we discussed the events of my accident and I was asked what I thought my next stage of training should be. I requested that I be considered for posting to an advanced flying school in Canada to complete my pilot training, having now achieved 130 hours in American aircraft.

I was instructed to report to a Group Captain on the board the following day for their decision. On attending this appointment I was told that they would agree to my request but I must also give written agreement that I would convert to twin-engine aircraft and stay in Canada for at least one year as an instructor. After much thought I declined their offer and opted to be retrained as a Navigator/Bomb Aimer at a school in Picton, Ontario. As my navigational training had already been concluded in America it was only a matter of a few night cross-country exercises to complete this part of my course, plus the written exams. The bombing and gunnery aspects were completely new, including theory and practice.

I graduated at the end of November 1942 and during my stay at Picton I had the opportunity of flying over and photographing the Niagara Falls. I was also able to make two visits to the Falls.

Other places visited were Hamilton and Toronto, the latter was visited on a number of occasions. It was at Picton that I met up again with Carl Hurlington and Jimmy Milichip both of whom had been sent back for retraining from pilot courses in Canada. Carl and I stayed together up to squadron allocation in North Africa.

RETURN TO THE U.K.

We embarked at New York, along with 30,000 other servicemen, on the Queen Elizabeth I – two weeks before Christmas 1942. The journey to Greenock (Glasgow) took four days and there were no escorts as it was considered that the ship could out-run the ‘U’ boats.

Only one cooked meal was served each day and every individual was given a ticket which showed which mess and meal time, which was part of the 24 hour serving. Supplementary food could be purchased from the various shops on board [sic] It was an uneventful journey and quite the opposite to the out-going one.

On arrival in Glasgow we were held for three days on board before it was our turn to be ferried ashore, after which we entrained for the RAF centre at Harrogate.

11

[Page break]

[Newspaper cutting]

Last week saw the departure of another contingent of British Pilot Officers, lads who had, many of them, passed through stages of their training at Maxwell and Gunter Fields, at Selma’s Craig and Dothan’s Napier, and have since been stationed as instructors at various points in the Southeast. Many of these chaps will remember Montgomery as the site of their “getting acquainted” with America, and many of them have formed ties with our town which will endure long after this present war is history.

When, some twenty months ago, Montgomery was invaded by the British, our capitulation was prompt. We fell before their onslaught like a Sicilian village before our own advancing troops. Into hundreds of Montgomery homes these cadets of the RAF were invited, perhaps a little doubtfully, but most of them quickly established themselves as wholesome lads, a little different in surface mannerisms and speech, but actually very like American boys, and very happy to find a friendly welcome in a strange land.

What began as a gesture of Montgomery’s hospitality developed, often, into fast friendships, and many Montgomery homes became “home from home” for youths from Yorkshire and Wales, Londoners and Scottish lads. RAF blue was a common sight on Montgomery’s streets. And, as the training program progressed, RAF men who had trained here began to take part in the raids over France and Germany and in other theatres of war. Montgomery is represented on these RAF sweeps over enemy territory just as it is represented in the actions of our Flying Fortresses.

Now the sight of an RAF uniform has become a rarity. With the exception of those who sleep on the hill above Montgomery, the RAF trainees have taken their wings and gone to the combat areas. They write back to Montgomery as if writing home, and Montgomery has a warm place in their hearts. Almost without exception they want to return in happier times to revisit this heart of the deep south.

“I know you’re glad to be going home’ someone remarked to a departing officer The officer hesitated. “Well yes, of course But I shall be back…definitely”

Written by ‘Pop’ Stewart for the Montgomery Advertiser

[Photograph]

Receipt for diamond engagement ring

[Photograph]

Jessie Brown 1942

Below: Sister Eva outside No. 4 William Street, Lincoln

[Photograph]

[Page break]

I was eventually interviewed by Leslie Ames the cricketer, who decided that because of the extent of my pilot training I should be a better asset to the RAF by being posted to a Wellington Operational Training Unit acting as Bomb Aimer, second pilot and supplementary navigator. I wasn’t sure how I could cope with it all but I agreed to his suggestion. – The following day I was given Christmas leave.

At this point in my memoirs I must introduce Jessie Brown. I met Jessie during the brief time that she worked at Clayton Dewandre and we began to go out together between my attendance at evening college and also at weekends. This was the period between my acceptance for the RAFVR and actually reporting for training.

Before leaving Lincoln we agreed that if either of us met someone else we were quite free to go out with them. However, both Jessie and I corresponded on a regular basis during my stay in this country and also during my time in America and Canada. Also we spent my leaves together. When I returned from Canada we decided that our relationship was very special to us, even though we had not known or been together very long. It was during my Christmas leave that we decided to become engaged. We went to Gravesend to see my sister Eva who was in the ATS and was stationed there. She was a telephonist on a Heavy Ack, Ack Gun Site but managed a short spell off duty so we went for a meal together and shared all our news. We travelled back to London and stayed in a rather cold and drab hotel off Regent Street for the night and went to a jewellers called Hinds to buy an engagement ring. Jessie chose a white gold ring with five diamonds. The assistant in the shop gave her a diary and this diary and the receipt for the ring are together in our memorabilia. At the same time, whilst on leave, we decided that if I was again posted abroad we would marry before I left.

Imagine my surprise when on arrival at Moreton-in-Marsh O.T. Unit we were told that, on completion of our training we would be posted to 205 Group British North Africa Forces. This news meant very hurried preparation for our wedding to take place at the end of March beginning of April. With the very limited facilities available and rationing of food, clothes, etc., the planning of such an event was very difficult and celebrations had to be extremely limited. The flying weather conditions during the first three months of 1943 were atrocious and our wedding date had to be postponed on two occasions but everyone was very understanding about these changes of plan. However, it did make life rather difficult for Jessie and others trying to make final arrangements.

The first and most important stage of OTU training was to “crew up” with other members of aircrew who it was thought could work as a team. I was a member of a crew made up of Pilot – Cyril Pearce – also a 42H class member in the USA but at different air bases – Jock Taylor (Scottish) navigator – Jock had joined straight from college and was the youngest crew member; Jack Morvel – WOP/AG and hailed from Bury – said he dyed to live but now lived to die – very encouraging and jovial character; Ted Peters – London – rear gunner.. [sic] Ted was a bit of a loner but we always encouraged him to join us in our out-of-base activities, mainly in Moreton, which at that time was just packed with airmen. Our crew was all NCO, and we knitted together very well. Most of our training was night flying on long cross-country exercises – Bulls Eyes – going from cities in England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland, carrying out various laid down routines such as infra-red simulated bombing of docks,

12

[Page break]

[Photograph]

19th April 1943 – St. Swithin’s Church, Lincoln

Carl Harlington, Enid Scott, Eric Scott, Jessie Brown, Eva Scott, James Brown

[Picture]

[Page break]

factories etc., which would record on camera for accuracy. On some occasions the cloud base was so thick and low that we never saw the ground from take off to landing and all navigation was done by dead reckoning and Astro-shots. Our accuracy in locating “targets” and turning points were very hit and miss, hence the postponement in completing our training. Some crews were lost during this period, either crashing in the Welsh or Scottish mountains or from the mechanical failure of the aircraft. It was also during this final part of our training we had to “stand to” for participating in a 1,000 bomber raid on Germany. I never found out the intended target because it was cancelled prior to briefing.

Our training completed – not without a few hair-raising experiences, we eventually went home on “embarkation” leave.

Jessie and I were married at St. Swithins Church on 19th April 1943 and our reception was in the ‘Gym’ room of the Rose and Crown Inn at the junction of William and Dale Street, Lincoln. We really appreciated the number of local people who helped us and we didn’t seem to miss out on anything with regard to food. Carl Harlington, who was also at Moreton and who hailed from Thorne, Nr. Doncaster, was my best man, but he was the only RAF person present, though one or two others were invited.

Jessie and I spent our wedding night at my sister Mary’s house in St. Hughe’s Street, Lincoln and the following day we travelled by train to Stratford upon Avon where we stayed in a B & B which we found on arrival – address : Sheep Street. After three days we returned to Lincoln as my leave was completed.

On my return to OTU I found that Cyril Pearce had also married during his leave, to a WAAF – Doreen – who was stationed at Gloucester. They married on the Saturday and we on the Monday.

Our final stage at Moreton was to “pick up” a new Wellington aircraft from a dispersal airfield near Gloucester and fly it on a number of exercises to ensure that everything functioned satisfactorily before taking it out to North Africa. As this exercise usually absorbed three weeks of our time, Cyril and I arranged for Doreen and Jessie to join us at Moreton for a week, I.e. the last week prior to departure. We stayed at the “Wylwyn Café” which also let rooms. One of the events which stays in my mind was our visit to the circus at Moreton. We all went along including Jock Prentice – another pilot who had also been married during his leave and whose wife had joined him at Moreton. The circus acts were extremely poor but what topped the lot was the smell – particularly when they let the lions into the “arena”. One can imagine the shouts and comments which ensued from a few hundred airmen!

We learned during this last week at Moreton that Doreen was AWOL from Gloucester, so Jessie and Jock’s wife loaned her civilian clothes to wear to hide the fact that she was a service woman, bearing in mind that the Service Police were well represented at Moreton and the surrounding area. The final day arrived when we had to say goodbye to our wives and walk to the airfield knowing that we would be flying that day, 27th May 1943 on the first leg of our journey to North Africa – which was from Moreton to Portreath in Cornwall.

13

[Page break]

OPERATIONAL TRAINING UNIT

MORETON-IN-MARSH

[Picture]

[Picture]

[Page break]

We stayed overnight at Portreath and on 28th May at 6.30am took off and set a course to go around the tip of France, across the Bay of Biscay, momentarily seeing the coast of Portugal and Spain and crossed the Moroccan coast at Casablanca. We then corrected course for our overnight destination at Ras-el-ma. On landing, at approximately 3.30pm British time, i.e. a nine hour flight, we were relieved to open the hatch and climb out. The air temperature suddenly hit us as we stepped onto the ground and we were surrounded by black people (local) in strange uniforms and cloaks and even stranger rifles and other firearms. This was the guard for our aircraft. RAF Ground Personnel took us to report in, and then to the “canteen” (tent) for our meal before going to our billet to make our bed for the night. During the late afternoon, Cyril and I changed the engine coolers to the tropical type as instructed at Moreton. We took our tropical khaki uniforms, with the “long shorts” as issued and our Blue kit had also been changed to khaki to “merge” with the desert sand.

On 29th we set course for Blida near Algeria which was the Headquarters of 205 Group. This took us across the Atlas mountain range which was a truly magnificent sight. This flight was only of four hours duration.

My only significant memory at Ras-el-ma was when we started the engines to fly to Blida. It was my job to prime the engines and then give Cyril the “thumbs-up” to crank them and, if they didn’t fire straight away I gave another pump on the primer which was at the Nacelle. Normally three pumps were required to get the engine – a Hercules Radical – to fire. No-one told us that in warmer climates two pumps were adequate and consequently flames poured out of the exhaust and burned my hair, eyebrows and singed my eyelashes. The smell was terrible but luckily I was not injured in any way. The second engine was started with two pumps and yours truly stood well back.

On landing at Blida we were told that we would be staying there the following day. This station’s billets were ex-Foreign Legion and the beds were curved upwards towards the centre from top to bottom. Here we encountered for the first time the French Loo!! We never thought we would manage to cope with it but practice makes perfect!

We went into Algeria the next day and saw oranges growing on the trees in the streets, experienced our first Arab Souk and the way of “hard bargaining” before purchasing anything. We had received some pay in Francs before going into town but, apart from buying “lunch” and coffee I can’t recall paying for anything else.

On 31st May we once again took off and set course for Kairouan, Tunisia. It was a three hour flight and we landed at 3.0 pm, having had to circle for thirty minutes because of exploding oil drums at the “airfield” which had been “touched-off” by the heat of the sun.

Kairouan was a number of white buildings just a mile or so from the airfield. This airfield had previously been a cornfield and the stubble was very much still in evidence. Steel, interlocking tracking – made in USA – had been laid on top of the stubble to form the runway and of course it became very hot and was the main cause

14

[Page break]

[Photograph]

[Page break]

of tyre bursts, of which there were many. The accommodation was all tented as was the various messes, because the squadrons were a mobile unit. The two Wellington Squadrons – 142 and 150 which had been sent from Waltham, Lincolnshire had been giving tactical night bombing support to the 1st Army which had landed at Bone. The “Desert” Wellington Squadrons who were now also based around were 104, 40, 37 and 70 and further support was provided by a squadron of Liberators, South African manned, and one of Halifax’s. These night bomber squadrons formed 205 Group and could produce between 80 and 100 aircraft for a night’s operation.

FIRST OPERATIONAL TOUR – 142 SQUADRON

I flew my first operation with Sergeant Cox, his B/A was sick. He had completed two thirds of his tour and Jock Taylor and I shared his tent. The target was a small island occupied by the Italians and from which they could attack our shipping. It was only lightly defended from air attacks and it was an “easy” target. This operation was one June 9th and the island, Pantelaria. (see log book).

We didn’t fly again until the 19th June when we flew as a complete crew – the target was Messina. This target was just the opposite to my first trip and we learned very quickly how to shorten the bombing run to a minimum and weave to avoid the AA shells which, on all major targets, proved to be very accurate. Sergeant Cox and his crew failed to return on this trip, which came as quite a shock to Jock and myself, reminding us that we were very vulnerable.

We continued to attack targets in Sicily and the area in Italy near to Sicily, in readiness for the invasion which took place on the night of July 9th when we were told to stay over our targets for at least thirty minutes dropping one bomb at a time and attracting the searchlights which we must then machine gun. Jack Morvel went into the front turret for this time over the target, which for us was Syracuse. Major targets such as Naples, Leghorn, Salerno, Pisa and all the airfields, were heavily defended by both AA guns and fighter cover. We had a few close shaves and there were a number of occasions when the AA shells exploded and splattered our aircraft and the cordite passed through the fuselage. On one particular trip over Naples when we become coned in the searchlights, Cyril had to throw the aircraft around to try and escape because the gun-fire was uncomfortably close. Jack Morvel was hanging onto flares in the tricel shute ready to release them when I warned him what was going to happen. The sudden, almost vertical bank that Cyril made caused Jack to lose balance and he fell into the side of the Elsan toilet which promptly broke loose and emptied its contents all over him. He wasn’t ‘flavour of the month’ for days after and had to replace his uniform battle dress. We did however manage to locate and bomb the target and return home – but had to make a second bombing run.

Our first tour was completed – thirty eight operations – by a visit to the Civitavecchia marshalling yards on October 3rd 1943, i.e. June 9th had started a four month period.

During that time I wrote and received many letters from home and received parcels with a variety of contents. We were entertained by professional artists on make-shift stages in the open air – names such as Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Dorothy Lamour, Charlie Chester and others. Members of the War Cabinet made visits to the Group

15

[Page break]

142 SQUADRON, NORTH AFRICA – JUNE 1943

[Photograph]

From left to right : Ted Peters, Eric Scott, Jack Morval, Jock Taylor, Cyril Pearce

[Photograph]

from left: Ted Peters and J Prentice with two crew who were killed over Naples July 1943

Our camp near Kairouan, Tunisia

[Photograph]

[Page break]

and told us what was and was not happening and why. We complained about the rations – mainly melted bully beef and biscuits, and the cigarettes that were issued. They changed the cigarette packets from ‘V’ to Woodbines, the contents remained the same, terrible. Fortunately we could purchase various other true brands from the Sergeant’s Mess.

We made several visits to Sousse, Hammamet and other smaller coastal places for a dip in the Mediterranean.

The lovely white walled city of Koirouan was a myth, it smelled to ‘high heaven’ and we couldn’t go to the Souk unless there were five or six of us together. The Arabs were definitely objectionable, probably because we were very tight in our bargaining at “tent level”. They did however win the “top award” when they took a tent whilst five men were asleep inside!! It was quite a shock to the occupants when they awoke.

Water allowances were very limited. The daily ration for a tent of five was a five gallon drum. This had to be for washing ourselves, our clothes and for drinking. The drinking water was kept in a hole just outside the tent, using a brown pot jug which kept the water at an acceptable temperature.

The air temperatures were very high during the day but were pleasantly cool at night after sunset. It was not possible to touch metal exposed to the sun after 10.0am and it was common practice to fry an egg on a metal plate in the sun. Our wash basin was an upturned tin hat with the inside removed and fitted into the tail fin of a bomb. Other improvisations such as making a comfortable bed frame and raising it from the ground away from dung beetles, scorpions, etc. were introduced within days of arrival or were “bought” with cigs, chocolate, etc., from crews who had completed their tour and were leaving.

Flies were a big nuisance, settling on food and spreading disease. Gyppy Tummy and Dysentery were experienced by virtually everyone and ‘having the runs’ was no fun at all.

Jock Taylor went down with yellow jaundice and was in the hospital tent for at least a week. He perspired considerably and every day his shirts were encrusted with salt from the body. His feet were also very odorous – but he did consent to leave his socks off during non-flying hours!

We had to be very careful not to get sunburn as this was a chargeable offence if it prevented anyone from flying.

Our posting to Tunis arrived and we were to stay at the transit camp for further instructions, presumably to await either air or sea transport to the U.K. During our stay in Tunis we met ‘Poni’ (the only name we knew him by). He was Maltese and his mother and sister, together with himself and his horses escaped from Malta because of the siege and came to Tunis where he continued to earn his living as a jockey, with his horses pulling a ‘cart’ on two wheels around the local race tracks. They appeared to be a wealthy family and he took us around Tunis for dinners in local hotels and objected then we insisted on paying for an occasional meal.

16

[Page break]

PALESTINE – MAY 1944

[Photograph]

Y.M.C.E. Building – Jerusalem

Right: The British War Cemetery

[Photograph]

[Photograph]

‘Mount of Olives’

[Photograph]

‘Garden of Gethsemane’

[Page break]

We also visited Carthage, the construction of which astounded us, with the running water and drainage system. This ancient city is a must to visit for anyone travelling in the area.

We had a severe shock when our posting came through. Only Jock Taylor was returning to the UK because of his jaundice, the rest of us were to fly to Cairo by Dakota, have leave and then proceed to Palestine where a new Operational Training Unit was being opened to instruct RAF personnel coming through from Rhodesia, South Africa and other Empire Training countries, prior to joining 205 Group.

We flew from Tunis across the Sahara Desert, visiting Tobruk on the way and landed at Cairo airport. We were taken to Heliopolis, a large transit camp about five miles out of Cairo and were incarcerated there for three weeks.

Cairo was visited almost daily. We had lots of back pay to draw upon and we visited a number of shows and night clubs. Jack Morvel blotted our copy book on one occasion when a troop of dancers were caterpillering off stage and he promptly dashed onto the stage and joined the end of the line. We had to leave but we had seen the show at half price. The Arabs in Cairo had to be watched very closely. They would steal anything, even the wealthy merchants from the Souk area couldn’t be trusted.

Eventually we left Cairo by a train which had wooden lattice seats, for two days of journeying to Tel-Aviv. Our bums were numb by the time we arrived! Upholstered seating was out because of the bugs which abounded in the Middle East and all bed legs had to the placed in tins partially filled with paraffin to prevent the bugs getting into bed with you!

Our destination from Tel-Aviv was 77 OTU Qastina. The station was only partially complete when we arrives and we were the first “instructors” to enter the station. The Sergeant’s Mess had not been completed at that stage and our aircraft had not arrived.

We spent Christmas 1943 on the Station. The accommodation was brick built blocks with three persons to a room. We had good beds, good showers new ‘mossie’ nets and plenty of storage room. The temperatures were quite moderate and we had to wear our Blues during the early part of the year.

Most of the construction work was being done by Arabs with RAF supervision. They would only work when they needed money and would arrive on their donkey, hobble the two front legs and report for duty – all very slowly. Occasionally we would unhobble a donkey, slap it on the rump and then at the end of the day watch the face of the owner then he found it was missing. They always dramatised everything that happened to them.

The airfield had been built on a small plain which was also the grazing area for local village animals. This resulted in considerable difficulties controlling aircraft movements because the Arabs would drive their sheep, camels, etc., across the airfield and runways at random. We tried to discourage them by rounding up their animals,

17

[Page break]

BETHLEHEM

A Judean Home

[Photograph]

Mother of Pearl Workers

[Photograph]

TEL-AVIV

Boulevard Rothschild

[Photograph]

Habimah Theatre

[Photograph]

HAIFA

The Road to Mount Carmel

[Photograph]

Technicum

[Photograph]

[Page break]

putting them into a compound and then insisting that they pay a ‘fine’ to get them back. The local Mokta (Mayor) visited us frequently and we prevailed upon him to stop the villagers from crossing the airfield. The climax came when a Defiant hit a camel which was crossing the runway. Unfortunately the aircraft was a write-off and we didn’t think much of the camel steaks either!

Eventually we were able to educate the Arabs to keep off the runways and, if they needed to cross, to wait for a green Aldis from the control tower. The Arab women could carry very heavy weights on their heads and this was demonstrated when two of them dropped bales of compressed straw onto the runway – we had to use the 15 cwt Chevrolet to drag them clear.

Whilst in Palestine we took the opportunity to visit the sights mentioned in the Bible. Jerusalem, Gol-Gotha, Haifa, Sea of Galilee, Bethlehem. The Jewish people were not kindly disposed to us. It was the period when ships with European immigrants were being turned away and would-be leaders were conducting terrorist activities. It was necessary to always be on the alert against attack.

Our main entertainment was either visiting Tel-Aviv for the day, being invited to the Polish Armoured Division near Ramalah, or having a dance in the Sergeant’s mess. The ATS and WAAFs were brought in by truck for these occasions.

When a course of ‘pupils’ passed out, one per month, they would invite their instructors to join them in the mess to celebrate the occasion. Many did ‘pass out’ but it was quite an event each month and I never needed rocking off to sleep on such nights.

The only other significant occasion I remember was P/O Izzard who was being taught to fly on one engine. I was also in the aircraft instructing a bomb-aimer. The screen pilot asked his ‘pupil’ to unfeather the port engine and return to normal power but unfortunately he feathered the starboard engine. We were too low to recover any power and the screen pilot had to crash land the Wellington in open country. Luckily no-one was injured but the aircraft was written off.

A week later I went for the weekend to The King David Hotel, Jerusalem. When I woke up the next morning my hair from ear to ear was on the pillow. I thought that someone had played a prank on me but soon discovered that my hair was still falling out. On my return to Qastina I reported to the M.O. who sent me to Tel-Aviv hospital. The Specialist went into raptures because he had not previously seen such a perfectly defined Alopecia profile of hair loss – just in line with the medical book. He brought into his consulting room both junior doctors and nurses but my question was what could he do about it and how quickly would it grow. The response was quite negative, I was told it would re-grow but over a period of months. The cause – delayed shock from the crash landing.

During the early part of my stay at Qastina I was sent to Ballah, down the Red Sea, on a Bombing Leaders and Instructor’s course. We worked fourteen hours every day either in the classroom or flying. We had to cram a three month course into two weeks. Immediately on arrival we were given a smallpox vaccination, apparently it

18

[Page break]

[Picture]

[Page break]

had broken out in the area. Fortunately for me it didn’t take. They tried three times but then gave me an exemption certification. The course was very enlightening – our tutor being a Squadron Leader and ex Oxford University Professor. I came second in the course with a 96% pass, beaten by a New Zealand Maori with 98% - a man with considerable retentive abilities.

I continued to teach at 77 O.T. Unit, Qastina, until the end of June 1944 when I agreed to team up with Brian Jeffares a NZ pilot to return for a second tour of operations, based at Foggia, Italy.

My other recollections during the stay in Palestine were the frogs and toads. Thousands of them came out after dark and made such a fearful noise when we walked across the grass verges and tarmac roads they just squelched under our shoes. The other was the cheapness of fruit. We had a plywood tea chest, normal size, which we would half fill on a bi-weekly basis. This would cost around five shillings. Huge grapefruit was stacked at the side of the roads, like sugar beet, and left to rot because of the lack of transportation to send them to other countries.

Jack Morval and I were, on one occasion, invited out to a meal with an Arab family by a Palestinian Policeman. Quite an experience. We sat on mats around a large dish full of mutton portions, including eyes, of which everyone present had to eat at least one. This was not pleasant but I did manage to swallow one with my own eyes closed! The Arab family were upper-class and very good hosts and could speak quite good English. I was under the impression that the Palestinian Policeman dined with them on a regular basis.

19

[Page break]

205 GROU – FOGGIA, ITALY 1944

[Photograph]

Our Crew see dots:: Brian Jeffries (NZ) Jack (Canada) Snowy Ayton (NZ) Eric Scott (UK) Jack Nichols (UK)

[Page break]

SECOND TOUR OF OPERATION – 205 GROUP

Our Crew:

P/O Brian Jeffares New Zealand Pilot

W/O Snowy Ayton New Zealand Rear Gunner

F/Sgt Jock Nicholls Scotland W/O Air gunner

F/O Jack Canada Navigator

F/Sgt Eric Scott England Bomb/Aimer

We left as passengers in a Dakota bound for Capodichino airfield, Naples, on 23rd July 1944. Our first touch down for refuelling was Benghazi, then further stops at Tripoli, Bari and finally Naples. Flying time was 11hrs 50 minutes but the duration of the overall journey was fourteen hours. (See Log book).

We were allocated to 37 Squadron of 205 Group flying MK X Wellingtons but these were now fitted with the MK X1V bomb sights, another Barnes Wallis invention and considerably superior and more accurate than the old MK IX. It worked on a gyroscopic principle so that if the aircraft banked the sight only rotated half the amount, thus keeping the sighting vertical. This enabled short bombing runs to be made with great accuracy and gave profound relief to the crew as this period was the time most likely to be hit by Anti-Aircraft fire and coned by searchlights.

Following two days of air tests to acquaint ourselves with the locality and hazards we were listed for our first operation to an aerodrome in the South of France. A trip of almost nine hours duration. We had two bombs ‘hung up’ and I had to chop out a section of the ‘cat walk’ above the station concerned and then release them manually over the sea.

Over the next twelve days we completed seven operations, two of which were to the Ploesti oil refinery complex near Bucharest. This was the third most heavily defended target in Europe with many searchlights, light and heavy AA guns and, I have since learned, a ratio of two fighters to every bomber.

Our losses were very high in 205 Group, around 10%, but not nearly as much as the Americans who followed us on daylight operations. They lost well over 100 aircraft each day.

Our first operation on Ploesti was quite reasonable and we were not coned, although the gun fire was accurate and the smell of cordite in the plane was quite unmistakeable we came out unscathed. The next attack was quite the opposite. We approached the target at 15,000 feet and were at least three miles away from the aiming point when a master searchlight came straight onto us, followed by at least five others. We corkscrewed, dived and did every manoeuvre possible but could not get rid of them. We were then down to 8,000 feet and being hit by light and heavy AA fire. We did the shortest bombing run ever and then continued to take avoiding action, losing height all the time. We levelled out at 700 feet, at last free of the defences and about seven miles from the target. We saw a number of aircraft being shot down and much air to air firing by observing tracer fire. We knew that some of the fires on the ground were dummies and that some of the ground explosions were to make us think that

20

[Page break]

[Drawing]

[Page break]

more aircraft were crashing than was the case. However, our losses on that occasion were high.

Following the Ploesti trips two crews in our Group refused to go on any further operations. They were court martialled and accused of ‘lack of moral fibre’, lost their rank and brevet and sent to detention. I often wondered whether the court of officers presiding had ever been to Ploesti or any similar targets. It was a very frightening experience especially with such a small force of aircraft.

We pressed on, operating through August, September and into October. Being an experienced crew we were sometimes called upon to carry out Path-finding, when we had to locate the target using flares, in Chandelier then make a second run to drop target markers of either Red or Green, then a third run to drop our bombs. Not very healthy and also we were not equipped with ‘H2S’ or ‘G’, blind target identification aids, as fitted to all four-engined aircraft operating from the UK.

Some of our operations involved dropping mines on the Danube which prevented, delayed, or damaged barges being towed with German supplies to their front lines in Hungary, it particularly restricted the supply of oil to their forces in Italy and Germany.

Dropping mines was known as ‘Gardening’ and each crew were given a ‘Bed’ or stretch of the river in which the mines must be delivered. Naval officers briefed and de-briefed us on these occasions. We usually carried four mines. When about 100 miles from the target and depending upon the terrain, we would drop to between 600/700 feet to be under the Radar beams. As the river came into view, bearing in mind that it was always a full moon situation, we would drop to 200 feet. On identifying our Bed we would further reduce height, sometimes to 100 feet before releasing the mines. This ensured that the mines would not break up on impact with the water.

Inevitably there was much light gunfire from the banks and also rocket launches on barges in the river. The rockets whistled past the aircraft but we were never hit by either of the defences and we didn’t waste time getting away.

One of our squadron crew was shot down over the river on one mine laying trip but they managed to ditch, swim to the bank and three weeks later arrived back on the squadron. We wanted to know why it took them so long!

With the Russian advance, guns and fighter aircraft became even more concentrated and targets more difficult to attack, consequently our losses also increased because of this.

About the middle of October, Wing Commander Langton, our C/O sent for our crew and told us that the Group was converting to Liberators. He said that our tour of operations would be completed in the next week or so and that we would then return to the UK. It was not worth the expense of us converting for a few operations. The following day I filled in the necessary forms to apply for a commission as I considered that this would be more beneficial to me on my return than a Warrant Officer rank

21

[Page break]

[Photograph]

Beside the main road from Bucharest to the famous oil town of Ploiesti, lies the beautifully tended Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery. While British Defence Attaché in Romania (1979-82) the author became curious to know how the 80 British and Commonwealth airmen, who lie in this peaceful place, met their deaths between May and August 1944.

He discovered that they were from the RAF’s 205 Group which, flying from airfields in the Foggia Plain of Italy, was the night bomber component of the Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force. They had lost their lives during the sustained day and night offensive against the Romanian oil industry and its distribution network, the transportation system supporting the German front in Moldavia and the mining of the Danube.

The cost to the Group, against these well-defended objectives – rated third after Berlin and the Ruhr - was 254 aircrew. 154 lost their lives, 73 became prisoners, while 27 evaded capture and returned to Allied lines after many adventures. 46 Bombers were lost.

Patrick Macdonald’s account of these operations is based on the contemporary official reports and intelligence assessments fleshed out by the recollections of many of the men who were there from all corners of the Commonwealth.

‘…a riveting story, well organised and well told… Patrick Macdonald’s book convincingly justifies his assertion that this bomber offensive, though little publicised at the time was no side show when set against other events nearer to the main arena of the war and for those who took part in it.’

British Army Review

[Page break]

which was imminent. I was interviewed the following day by Wing Commander Langton who said that he would forward a recommendation to Group HQ without delay.

On the 17th October we carried out what we thought would be our final operation on a marshalling yard in Yugoslavia. However, on the afternoon of the 21st we were asked to fill in for a crew whose pilot had reported sick. The target was Maribor marshalling yards in Yugoslavia. Everything went wrong on that day. The aircraft was an old MKIII and one engine was ‘playing up’ when we checked it out in the afternoon. When we went to take off the engine was still showing high mag. drop. Further work was carried out but eventually we took off fifteen minutes late and with a slower than normal aircraft. Our arrival on target was at least twenty minutes behind schedule and, of course, we were on our own. After dropping our bombs we turned for home and tried to do a bit more catching up. On approaching the Yugoslavian mountains we were attacked by a German fighter from below. No-one saw it as it was in a blind position. The damage was mainly to the petrol tank on the starboard side, so I switched both engines to that tank to save fuel.

Despite the fact that we dog-legged, changed height and changed our position every few minutes, we were again attacked about fifteen minutes later and on this occasion the aircraft went out of control. Brian gave the order to abandon the aircraft. I opened the front lower entry/escape hatch, saw Jock and Jack the navigator go forward, then picked up Brian’s parachute and gave it to him, meanwhile he was trying to slow the descent of the aircraft which was quite considerable. On trying to clip on my own ‘chute I could only feel a clip on the left side – the right hand clip seemed to be flattened. Being dark I couldn’t see what had happened. There was very little time to ponder the problem because we were over the mountains which I could see from the side window. My only chance of survival was to jump and hope that the canopy shrouds would not entangle so that the ‘chute would open.

I said a very quick prayer asking God to give me a safe landing and then swung out of the forward hatch. I then felt for the rip cord handle and pulled it. Almost immediately there was a very load crack and I was jerked into a floating situation. At the same time I saw our aircraft explode on the ground. Not being sure of my ‘angle of dangle’ I was not ready when I hit the ground with considerable force. My face hit a boulder on the mountain side – I’ve never looked so good since. It was pouring with rain and numerous dogs were barking, presumably because of the exploding aircraft.

HOSTAGE/PRISONER OF WAR

The first thing I did after releasing my parachute was to thank God for my life, and also prayed that somehow Jessie and the family would know that I was safe.

After wrapping myself in my parachute for warmth and protection from the rain I went to sleep.

The tolling of a church clock and the barking of dogs woke me at daybreak. The rain had ceased and looking around I realised that I was about one third of the way up the mountain and it was mainly boulders and scree around and below me. My face was

22

[Page break]

[Photograph]

[Page break]

stiff and sore and coated with dried blood on one side. I collected my parachute into a manageable ball and then examined the harness. The right hand clip was torn away and the remaining metal, near the harness, was very distorted. It was apparent that either a bullet or shell from the fighter had hit the clip and torn it away. The thought of such a ‘close call’ made me shiver and I was thankful for my safe deliverance. I hid my parachute between a boulder and the ground on the face away from the valley.

There was a farmhouse near the bottom of the mountain in a concealed position. I watched the activity at the house for at least three hours. The farmer came out of the house with his dog, followed by a woman who assumed to be his wife. Later, a girl who was probably about twelve years old and a boy 8-10 years started to do tasks around the farmhouse. By this time the chimney was smoking. Looking at my watch I saw it was around 10.0 am when they all returned to the house. At 11.0 am I decided that the family were harmless and that I would approach them for assistance to try and contact Tito’s Partisans.

I didn’t have any problems negotiating the descent and arrived at the farmhouse unseen. The lady opened the door to my knocking and audibly gasped. I explained who I was with gestures and she called her husband. When asking them for help I tried to explain that my parachute could be retrieved and given to them in return. The man came with me and helped to bring my parachute down to the house. I offered him a cigarette and, with the ‘hot end’ I burnt a piece of the canopy as a keepsake. What I didn’t realise was that the farmer had sent his son the alert the military authorities.

On the boy’s return the farmer motioned me to follow his son, giving me the impression that he would guide me to the Partisans.