The lucky crew

Title

The lucky crew

Description

Memoir including photographs of the crew and aircraft. Thomas Jones was a flight engineer on Stirling and Lancaster and completed 64 operations on two tours. Describes early life, joining the RAF, selection and training., crewing up and first posting to 622 Squadron flying Stirling at RAF Mildenhall in September 1943. Gives account of activities and operations on first tour. Squadron converted to Lancaster and he was then posted to 7 Squadron at RAF Oakington. On completion of second tour went to 1332 Heavy Conversion Unit Transport Command near Belfast, Norther Ireland. Lists crew with decorations which is followed by account by his son Peter Jones.

Creator

Spatial Coverage

Coverage

Language

Format

Thirty-three page printed document

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

BJonesTJJonesPWv1

Transcription

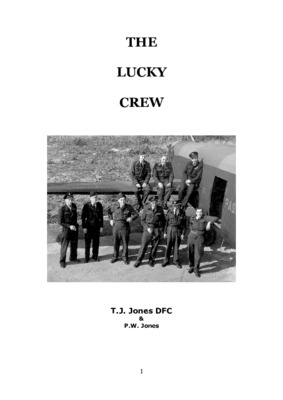

THE LUCKY CREW

[photograph]

T.J. Jones DFC & P.W. Jones

1

[page break]

Introduction

I, like many children born in the mid-fifties, grew up surrounded by reminders of World War Two. There were the L-shaped trenches, in a field, near my home, which had housed searchlights and anti-aircraft guns. There were also trees and telegraph poles with their fading white collars.

So it was that I would ask that question all little boys asked their Father in those days, “what did you do in the war, Dad”?

My Father would reply, modestly, that he had been a flight engineer on bombers. That was all he ever said no details, no bravado, no hint of heroism, or the horrors he had endured.

In time I learned that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but never discovered why.

That is how it was until his sad death on 28th January 2004.

My Mother and I were sorting out some of his papers, kept in an old wartime suitcase, when we came upon a small green notebook. This notebook was to unlock Dad’s story. For there were the memories he never told.

It would appear that he had put pen to paper in the 1990’s, some fifty years after the war. Reading that book, so shortly after his death, made me very sad. It also made me immensely proud of the modest Father I had known and loved for almost fifty years.

And what of the DFC, there was no mention of it. Did his natural modesty prevent him from recording why he was awarded it, or were the memories too painful?

The following pages tell his story.

Peter W Jones

[italics] When we first arrived the command “Attention” was followed by a noise like load of house-bricks falling of a lorry and a cry from the drill corporal

‘You dozy lot, wake up now. Bags of swank.’ At the passing-out parade six weeks later the same command produced a noise like a rifle shot. As we marched away along the promenade, rifles in line, heels crashing in unison, arms swinging shoulders high, we had what the corporal had wanted to see, Bags of swank!

I remember R.A.F. Cosford and the flight mechanics course. how young and eager we were, picking up the service slang and clichés. On arrival we were assigned to wooden huts with eight double-tier bunks down each side, a plain wooden table with two benches, andf a small stove in te middle of the hut.

The first week of every new entry was spent on fatigues. Peeling four feet high piles of vegetables. After every meal the floors and tables of the vast dining halls had to be cleaned and polished.

Guard duties, fetching carrying, pushing, scrubbing. We were at everyones beck and call, but it was fair, every new intake did it.

Wednesday afternoons were spent on field exercises. Prowling through muddy fields and woods, everything that involved mud and muck. Camouflage, grenade throwing, bayonet practice.

[page break]

Anti-gas procedure, groups of us standing in the gas chamber and being ordered to remove our respirators to prove that the room really was full of gas. Dashing out into the fresh air, coughing and spluttering, eyes streaming.

Wednesday nights were domestic nights and everyone was confined to barracks. Everything in the hut had to be cleaned and polished. Fire buckets and extinguishers, every inch of floor space to be polished and sparkling. Table and benches to be scrubbed. The last man coming out backwards the following morning polishing out the last foot prints ready for the flight commander’s inspection.i remember the precision of kit inspection. Each bed laid out with equipment, each piece in it’s correct place and every bed identical to the next.

The months of learning and cramming. Class-rooms and hangars, engines and airframes. Aero-dynamics, physics, mechanics. Hydraulics and pneumatics, fuel systems, carburation, airscrews, ignition systems and instruments. The form too. Maintenance manuals and periodicity talks. A seemingly endless number of subjects, all to be absorbed and remembered.

I remember the parades and the marching to and fro. The sound of a youthful tenor voice in one of the huts singing ‘Always.’ The bugle call at reveille and a P.T sergeant stamping down [italics]

“The Lucky Crew”

2

[page break]

[photograph]

The crew, left to right:

Fred Phillips RAAF, Dave Goodwin RNZAF, Stan Williamson RAAF

Clive Thurston RNZAF, Ron Wynne RAF, Joe Naylor RAF

Thomas Jones RAF, Steve Harper RAF.

This photograph was taken in September 1944 shortly after the crew completed their tour of 64 operations and left 7 Squadron. The aircraft they are standing in front of is Lancaster PA964 MG-K. This was last on the night of 6th October 1944 during a bombing raid on Scholven-Buer. The eight man crew, that night, were captured and held in Stalag Luft 7 at Bankau, from where they escaped in April 1945.

PA964 had survived 244 hours of operationsal flying, much of it in the hands of “The Lucky Crew”.

3

[page break]

FORWARD

Thomas Jones’s memoir gives a vivid description of life in a bomber squadron Pathfinder Fo9rce. The account of his experience as a Flight Engineer on operations in Stirling’s and Lancaster’s depicts the stresses, strains and comradeship of a bomber crew and the extent of a flight engineers tasks.

Very few crews survived as many as 64 bomber operations which Thomas Jones and crew achieved (my own contribution was 60 sorties) so his memoirs form an important contribution to the history of Bomber Command operations and it’s crews.

Wing Commander Philip Patrick MBE DFC

[622 Sqd. Crest] [7 Sqd. Crest]

Squadron crests reproduced by permission of the Secretary of State for Defence.

4

[page break]

I remember a happy childhood, firstly in central Birmingham then the southern district of Hall Green. I didn’t dislike school. My early teens were spent under the threat of war, which was declared when I was eighteen.

The blackout became a way of life for six long years. The nights spent in the air-raid shelter, my mother asking me to come away from the entrance where I was watching the havoc, into the deeper safety of that cold damp cell.

I recall the scream of falling bombs and the shudder of the earth on impact. The noise of the anti-aircraft guns firing a short distance away, like great iron doors slamming, and the hissing rush of the shells fading away as they sped up to the heavens and the German bombers. I remember my sister weeping quietly when it all got too much for her. The metallic tinkle of shell splinters as they rained down on roofs and road surfaces. The reflection of a hundred fires on the cloud as my city burned.

I was both fascinated and appalled at the effects of the nights bombing. On my way to work, at the BSA, in the early morning light I was stepping over the rubble of houses that had been hit by bombs during the night. Of one house a solitary wall left standing and on the bedroom mantelpiece a clock still showing the correct time. A house with no roof and a six-inch wide crack from eves to foundations, and not a window cracked. There was a double decker bus on Coventry Road, Small Heath, standing vertically on its bonnet.

I volunteered for aircrew duties in the RAF, the excitement and the boredom, the laughter and the comradeship the like of which is rarely experienced in civilian life. The songs and tunes of the period, each one associated with a particular time, a certain place or face.

Most of us who survived in one piece had an easy war compared to many others. No wounds, disfigurement or physical pain. No years of imprisonment torture disease, starvation and despair. That is why there is little pain for me to sit quietly, fifty years on, in that little room of memories going back down paths which divide and branch like blood vessels.

I was sent to RAF Cardington in September ’42, with its huge hangers where the great airships were built in the 1920s, for aircrew selection. I can easily recall the aircrew medical where everything was tested, examined, poked and prodded. There followed days of written, oral and aptitude tests. I remember the first time I entered the dining hall, the volume of the WAAF corporal’s voice reducing the occupants to silence, and the embarrassment on realising that the order to “put that bloody cigarette out” was directed at me. After four days home again to await my call-up papers, which I received a few weeks later.

And so in October to RAF Padgate with hours spent waiting in different rooms during induction. Being issued with my identity discs and service number, to be memorised and will be remembered for the rest of my life. Ask the service number of any ex-service man who enlisted all those years ago and he will recite it without the slightest hint of hesitation.

I remember the outstretched arms laden with clothing and equipment in the kitting out stores. The WAAF’s singing “Jealousy” in the station cinema as the little white ball bounced along the words on the screen. I recall the train journey to the Initial Training Wing (ITW) at Redcar on October 17th ‘42, and especially Mrs.Thatcher of 4 Richmond Road. Ken Battersby, Chas’ Curl and myself were billeted with her for six weeks and she looked after us like a mother hen. She made sure we were correctly dressed each morning when we went out on parade. She treated us as though we were her own sons.

The wind was icy on the sea front as we learned foot and rifle drill, fumbling with numbed fingers at the rifle bolt and rear sight. We did route marches and assault courses

5

[page break]

in full battle order, reaching the finish gasping for breath, with a supposedly wounded man across our shoulders.

I learned on the rifle range that a 303 when fired from the shoulder didn’t produce the crack as when heard from a distance. It produced a heavy numbing thud inside the head. The following day it would only take the sudden rustle of a newspaper to set the ears ringing again.

When we first arrived the command “attention” was followed by a noise like a load of house bricks falling off a lorry and a cry from the drill corporal “you dozy lot, wake up now, bags of swank”. At the passing out parade, six weeks later the same command produced a noise like a rifle shot. As we marched away along the promenade, rifles in line, heals crashing in unison, arms swinging shoulder high, we had what the corporal had wanted to see, “bags of swank”.

It was then to RAF Cosford in early December and the flight mechanics course. How young and eager we were, picking up the service slang and clichés. On arrival we were assigned to wooden huts with eight double tier bunks down each side, a plain wooden table with benches, and a small stove in the middle of the floor.

The first week of every entry was spent on fatigues. Peeling four-foot high piles of vegetables. After every meal the floors and tables of the vast dining halls had to be cleaned and polished. Guard duties, fetching and carrying, polishing and scrubbing. We were at everyone’s beck and call, but it was fair, every new intake did it.

Wednesday afternoons were spent on field exercises. Crawling through muddy fields and woods, everything involved mud and muck. Camouflage, grenade throwing, bayonet practice. Anti-gas procedure, groups of us standing in the gas chamber, and being given the order to remove our respirators to prove that the room really was full of gas, dashing out into the fresh air, coughing and spluttering, eyes streaming.

Wednesday nights were domestic nights and everyone was confined to barracks. Everything in the hut had to be cleaned and polished. Fire buckets and extinguishers, every inch of the floor space to be polished and sparkling, table and benches to be scrubbed. The last man coming out backwards the following morning polishing out the last footprints ready for the flight commander’s inspection. I remember the precision of kit inspection. Each bed laid out with equipment, each piece in its correct place and every bed identical to the next.

There were months of learning and cramming. Classrooms and hangers, engines and airframes. Aerodynamics, physics, mechanics. Hydraulics and pneumatics, fuel systems and carburation, airscrews, ignition systems and instruments. Maintenance manuals and countless other books. A seemingly endless number of subjects, all to be absorbed and remembered.

There were also the parades and the marching to and fro. The bugle calls at reveille and the PT sergeant stamping down the wooden floor of the hut banging each bunk with a pick-axe handle, shouting at the top of his voice “parade in fifteen minutes, last man out is on a week’s jankers”. And there was the dreaded Trade Test Board at the end of it all, and the feeling of great achievement on making the grade.

The next step on the ladder was to RAF St.Athan in April ’43 and the flight engineers course. Was it to be Stirling’s, Lancaster’s or Halifax’s? Oh youth and innocence, it was all great fun with little thought of the future.

We were billeted in the same type of wooden huts as at Cosford and did the same fatigues during the first week. Most of us had been together since ITW, a lot of us only eighteen, not many over twenty. The Scots lads, Tommy McMeachan, John Mullens, Jimmy

6

[page break]

Cruicshank and John Gartland all killed. Taffy Lightfoot and Roy Eames died over Bremen. Bill Curry shot down and killed whilst still training. There was also Albert Stocker, Arnold Hearne and Jack Walker. How many blurred faces on the edge of memory survived?

I was selected to train on the Short Stirling, the biggest of the four engine bombers of the time, eighty-seven feet long and twenty-eight feet high with the tail up. It had a fourteen tank fuel system with inter-wing and inter-engine balance cocks. Hercules XVI sleeve-valve engines with two speed superchargers and epicyclical reduction gears. The SU carburettors were the size of a car engine. The Stirling was renowned for being the electrician’s nightmare with its miles of electric wiring

There wasn’t a single subject or component part of the Stirling that we weren’t lectured on. After the intensive Trade Test Board examination I remember the brevets and chevrons being sewn on our tunics, the regulation button stick length from the shoulder seam. The young faces didn’t seem to match the rank and many of them wouldn’t survive to wear the flight sergeants crown.

[photograph]

Tom Jones, aged 22

RAF St. Athan, August 1943

And so, in July 1943, to 1657 Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) at RAF Stradishall to be crewed up and to fly the aircraft we had been trained on. We were billeted in empty married quarters and reasonably comfortable but we soon discovered that they were directly in line with the main runway. All night long crews were practising circuits and landings and every few minutes an aircraft would roar overhead at fifty feet.

There is still another three weeks classroom work to do but now our instructors are not civilian technicians but veritable gods in our eyes, men who had completed a tour of thirty operations. There was no bravado about them but their eyes and faces showed a wealth of experience from which we were to benefit. When they lectured us we hung on their every word.

We were encouraged to visit the flight offices in our spare time, to get in as many flying hours as we could before being crewed up. I remember my first flight as a passenger. The pilot was a Canadian, flight sergeant Moore, who was still undergoing training. I’d always had the impression that an aircraft, once off the ground, flew straight

7

[page break]

and level. How wrong I was! We reached the dispersal and this great black monster and I climbed aboard with the crew, I had a few misgivings. Would I be airsick, would the height affect me? Some people couldn’t climb a ladder, and I had never been higher than the inside of a bedroom window.

We taxied to the runway, hesitated and then began the mad dash toward the other end. The aircraft’s thirty tons lifted off the runway and promptly began to sway from side to side and up and down, the wings actually flapped! The engines were nodding as if in mutual agreement on some topic of conversation. Looking down the fuselage toward the rear turret I could see the whole structure was twisting back and forth. I looked out of the window, a patchwork of fields, tiny houses and on our port quarter the airfield with its three intersecting runways. The height didn’t bother me at all but the continuous movement did. After ten minutes I quietly disgraced myself by being airsick. I, subsequently, flew over 300 hours before my stomach finally settled down.

Later, on the squadron, it became the practice for the ground crew to provide me with an empty tin every time we flew, daring me to make a mess in their spotless aircraft. This saved me from bankruptcy as squadron lore dictated that anyone sick on the floor of an aircraft had to pay the groundcrew to clean it up.

I was talking with a group of engineers in the mess, when an Australian flight sergeant pilot approached asking for me. He introduced himself as Fred Phillips and said that I was to be his engineer. A former insurance clerk from East St. Kilda, Melbourne and twenty years old. He was destined to be awarded the DFC before he reached twenty-one and awarded Bar for his DFC before his twenty second birthday. He introduced me to the rest of the crew. Dave Goodwin navigator, and Clive “thirsty” Thurston bomb-aimer, both New Zealanders. The gunners were Ron Wynne from Hyde Cheshire and Joe Naylor, known as John by everyone, from the village of Wymondham near Melton Mowbray. The wireless operator was another Australian, Stan Williamson from Punchbowl, Sydney.

Our first flight as a crew, on August 29th 1943, was a familiarisation, getting the feel of the aircraft. There were circuits and landings, during daylight and the same at night, over and over again until the different drills and check became automatic. We did three and two engined procedures, cross country flights and bombing practice. We flew 34 hours together, at RAF Stradishall, and were granted “fit for operations”. In my log book was entered my certificate, qualified to fly as flight engineer in Short Stirling’s Mk I and III.

On September 2nd ’43 we were posted to 622 squadron, at RAF Mildenhall. On arrival we spotted our first operational aircraft. It was parked in front of the flying control tower after landing from an operation the previous night. As we approach we could see it was punctured with jagged holes and the rear turret was a mass of battered twisted metal. Dried blood everywhere, a glove, a tuft of hair and a piece of jawbone with teeth still attached lay on the turret floor.

That night in the mess we asked how long it took to complete a tour of thirty operations. No one had ever known a crew that had finished a tour. I realised that we had reached the point where we were expected to pay, in kind, the cost of our training.

When we made up our beds that night no thought was given to who the previous occupant had been. We quickly learned that close friendships were not formed with other crews. A passing joke or a civil word sufficed. New faces appeared, sometimes for a few days, or a week or two, to disappear and be replaced by others. Their passing marked by a visit from the committee of adjustment to clear out their lockers and return personal property to next of kin. Their names rarely mentioned again. Morale gained nothing from speculation. Had it been quick as with a direct hit with flak, or a scrambling dash to get out

8

[page break]

of a blazing aircraft? A human torch falling to earth with mouth wide, in a silent scream of pain and horror? Forget it quickly! Do not dwell.

I remember there was always laughter and high spirits in the mess, we learned to laugh about flak and fighters, searchlights and crashes. If a pilot bragged about his good landings no one disagreed with him. Inevitably the day came when he misjudged it and bounced down the runway like a kangaroo. His life was made a misery for the next week. Every time he entered the mess all the pilots present deferred to him and wished they possessed his skill. Stories of silly mishaps did the rounds.

An aircraft on its take-off run had reached 85 knots when the pilot cleared his throat. The engineer, thinking he had asked for wheels up selected same and they finished up on their belly astride the railway lines two hundred yards beyond the runways end. This escapade earned an unofficial commendation on the mess notice board.

Flying whilst suffering with a head cold was discouraged as it led to sinus and inner ear problems. One lad had to report sick with a heavy cold and immediately a rumour was circulating that he knew the squadron was about to attack Berlin or Essen and was reporting sick to get out of it. This sort of thing happened all the time, but it was never vindictive, the victim enjoying the joke as much as anyone.

On an operational squadron the learning still went on, each of us learning something of the others jobs and duties. Ditching and parachute drills were carried out regularly when we weren’t flying, timing ourselves to see how many seconds it took us to get out. Bombing practice; cross country exercises in atrocious weather when visibility was less than the length of the runway. Flying in rain, snow and icing conditions.

There was also fighter affiliation, to practice the corkscrew. With the guns the bombers only defence against fighters, it was essential that we practice this manoeuvre with the help of Fighter Command. I recall the Spitfire’s curving arc of attack and the rear gunners call to “corkscrew port, go”. The horizon almost vertical, then swiftly up and to starboard over the cockpit canopy. Everyone hanging on tightly to the front edge of their seats, so as not to hit the roof. The feeling of weightlessness as the aircraft plunged away in a steep diving turn, the earth in front of the windscreen rotating clockwise as we lost height, the call “roll her, roll her”. The pilot pulling back on the stick to put us into a steep climbing turns to starboard. Again the mad dance of earth and sky, the gravitational forces pressing the body down and draining blood from the head; the cheeks and the mouth falling open. The relief as the fighter breaks off the attack, the earth and sky sliding back into place as we level off and assume course, and await the next attack.

It was during fighter affiliation that we discovered how manoeuvrable the giant Stirling was in flight. It was more agile than some aircraft a quarter of its size. However, it was a beast when manoeuvring on the ground.

Our first operation had been to lay sea-mines in the Katigat, a solo aircraft operation with a naval officer on board to trigger the mines. The next night Hannover, having to divert to RAF Tangmere on return due to flak damage to number 7 fuel tank. Two nights later mine laying in the Skaggerak; then Hannover again, Kassel, Ludwigshafen and Berlin. On these first op.’s we came back only three times on all four engines.

My station, when flying in Stirling’s, was at the front main spar of the wings where it passed through the fuselage, and I consequently saw little of what went on outside. The view from the astrodome was limited so when things were running smoothly I would go forward to the cockpit for ten minutes or so to have a look out.

I shall never forget the cloudscapes, climbing through thousands of feet of dark grey nothingness to emerge into a vivid blue sky with a floor of dazzling white stretching to the

9

[page break]

horizon in all directions. Flying along great canyons between the cliffs of cumulus. There was also nimbus, the cloud most respected by all airmen, with its anvil shaped head towering to altitudes we could never hope to reach. Flying through nimbus had us hanging on grimly as the aircraft is flung around by the air currents, us fearing that the wings would be torn off. There were continuous lightening flashes. The propeller arcs alive like Catherine wheels, and lightening cracking back and forth along the wireless aerials and guns. The tremendous energy generate4d within nimbus clouds is unnerving when experienced for the first time.

the sunsets were always beautiful with the changing colours of the clouds. From the brilliance of polished brass, to rose, pink, bronze, purple, and finally to black. All within a short time, but always warm. Dawns were different, they were cold. During the long boring flight home the first greying in the east would silhouette the swaying tail of the aircraft. The horizon slivers of grey-green light.even the first rays of the sun were always cold.

622 Squadron converted to Lancaster’s in November 1943. While the pilots and engineers were lectured by the engineer leader, two pilots were seconded to a Lancaster squadron for a few hours flying instruction then returned to instruct us. Flying in Lancaster’s meant that my station was next to the pilot. Five hours of training flights and we were away again. my logbook made up, qualified to fly as flight engineer in Lancaster Mk’s I and III.

Our bombing sorties took us to Berlin again, Schweinfurt, and twice to Stuttgart. By now we were one of the most experienced crews on the squadron and were selected to train for the elite Pathfinder Force.

We were sent to the Navigation Training Unit at RAF Warboys in March ’44. The bomb-aimer did a course on H2S equipment while I attended lectures on the bomb-site and bomb aiming. During our free evenings the navigator, Dave Goodwin, taught me how to use the bubble sextant and we spent several clear nights picking out the constellations and their stars. Dheneb, Altair, Betelgeux, Alderbaran, Arcturus, and a dozen more. From then on I had to take the sextant shots from the astrodome. We also attended lectures on pyrotechnics and target marking techniques. After nine hours of flying and six practice bombs on the range we were posted to 7 Squadron at RAF Oakington, near Cambridge, on April 2nd.

On arrival we discovered that the squadron C/Owing Commander Rampling had just been killed during a night raid. He was replaced by Wing Commander Guy Lockhart, aged just 27. He was killed four weeks later and replaced by Reggie Cox.

As a Pathfinder crew we were expected to complete two tours of thirty op.’s each with no rest period. Main force procedure was one tour of thirty op’s, six months rest as an instructor, then recall for another tour.

10

[page break]

[photograph]

The pilot would inform us “we are on the order of battle” and the butterflies in the stomach would begin to flutter their wings. They were always there, at the beginning because we didn’t know what to expect, and on subsequent op.’s because we did know. In those days it was a sign of weakness to admit fear but you could tell it was there. Normally quiet lads would chatter incessantly while the extrovert would withdraw inside himself. Others developed little quirks that they never had until their names were on the order of battle.

We would go out to the aircraft to carry out our inspections etc. then to the mess for lunch, but a ban on drinks at the bar. The aircraft would be take [sic] up for a night flying test to iron out any last minute snags. If it was a late briefing a couple of hours in bed, spreading a white towel over the blanket at the foot of the bed to indicate you require waking.

We would be woken with a torch shining on the face, a hand shaking the shoulder, and a voice saying “it’s time to get up”. Sitting on the edge of the bed, head sagging, desperately trying to wake up fully; while someone fumbles about in the dark, cursing, seeking the light switch. Little is said as we walk to the ablutions to wash and visit the toilets. A call of nature during a flak barrage could cause extreme embarrassment.

The pre-flight meal is usually something recommended by the aviation medicine people. A fried greasy dish, which is always disastrous for someone like me with an already queasy stomach, or baked beans which create gas and excruciating stomach pains as the atmospheric pressure falls as we climb to our cruising altitude.

I remember the pre-flight briefings and the walk past the armed guard at the door. The long room filled with trestle tables and benches, each one occupied by a crew. At the end a low stage and almost the entire wall covered by a huge map of Europe, for security reasons behind drawn curtains. A thick swathe of tobacco smoke hangs in the air. Everyone stands as the C/O arrives and the ritual begins.

The curtains covering the wall map are withdrawn and the target announced. A low murmur of voices rises from the assembled crews. Red tapes pinned to the map mark the route from base to the target and back, doglegged to squeeze between the ominous red patches which denote heavily defended areas, avoiding all but one, the target.

The intelligence officer is the first to take the stage with the latest information on the target, factories and products, railway yards etc. The state of the defences and positions of the night fighter stations along the route.

The navigation officer holds the stage for the longest period of time, going over the route. Times of take-off and set course, time and position of course changes rendezvous

11

[page break]

with the aircraft of other groups. “H” hour and the type of markers used, Parramatta, Newhaven or Wanganui. Codes, colours etc. and the inevitable time check. Each leader, in turn, taking the stage to divulge information relative to his section. Bomb aimers, gunners, engineers and wireless.

The Met. man with his charts, cloud information and prospects in the target area. Barometric pressures, temperatures, icing conditions and weather at base on return. The latter always bringing a burst of sardonic laughter from the crews but it was usually taken in good part, even on occasions eliciting a wry smile from the met. man himself.

The whole proceedings coming to a close with a few words from the C/O on the importance of a successful attack.

At a table at the other end of the room the adjutant is accepting the pocket contents of the crews. Wallets, loose change, last letters, even used bus and cinema tickets. All are placed in separate drawstring linen bags and tagged with the owners name rank and number, to be reclaimed on return. It never occurred to me to write a last letter. Was I that confident or thoughtless? On reflection, it must have been the latter.

The walk to the locker room is quiet and leisurely, different to the atmosphere in side. A noisy confusion of men and equipment, loud jocular remarks and laughter sounding a little forced. “Can I have your fried breakfast if you don’t come back?” “Yes, but what makes you think that you are coming back?” It all sounds so cruel and heartless now, but no one ever took exception to this type of banter.

While the gunners get into their heavy outer flying clothes, the rest of us don Mae West and parachute harness, pick up flying helmet, parachute pack and gloves. A WAAF driver would come to the door and shout “crew transport”.

All the WAAF’s I ever met were very efficient and went out of their way to be helpful and pleasant. Most of them could, with a smile, deflate the ego of a too adventurous lad, much to the delight of all present.

Several waiting crews clamber aboard with much scuffling of flying boots, and we begin the journey round the perimeter track to the dispersal points. There is a marked decrease in laughter and conversation now. The coach arrives at the first dispersal, “G-George” calls the driver, and a crew disembark under the nose of their aircraft. With a few mutters of good luck they slouch away. We drive on to “A-Able” and then us “O-Oboe”. We climb out of the coach, and with a wave from the WAAF driver, it draws away. This is when the butterflies in the stomach are at their worst. I pick up my gear and walk with the crew to the tail of the aircraft.

There is no ground crew to be seen. At any other time they would be laughing and joking with us, but not now. They will remain in their rough dispersal hut until we climb aboard before they emerge to prime the engines when we start up. No rules of security will be breached by them asking the name of the target, although they will have a good idea from the fuel and bomb load. They have seen it all with so many crews before we joined the squadron.

Aerodromes, in pictures and films, are mostly depicted as idyllic places. And so they are in Summer, the heat rising in shimmering waves over vast flat areas of grass and wild flowers and everything alive with birdsong. They rarely show the same scene in late autumn or winter, when the grass surrounding the dispersal has been churned up by vehicles into a sea of mud; which in the January frost is turned into ankle breaking ruts. These are the conditions ground crew work in, no protection against driving rain snow and bitter winds; the engine fitters and mechanics working fifteen or twenty feet above the ground on swaying gantries. They grumble and curse but all aircrew have great confidence

12

[page break]

in their skill and dedication. They take great pride in maintaining the cleanest and most efficient aircraft on the squadron, and woe betide anyone that bends it. The aircraft belongs to them, the aircrew only borrow it.

While the rest of the crew stood talking I would start my pre-flight checks. Tail unit control surfaces and tail wheel. Up the port side checking fuselage and wing surfaces, all engine cowlings in place and secure, pitot head cover removed. Examine undercarriage struts and also extensions for oil leaks. Trolley acc’. plugged in, tyres for damage and creep. Check bomb load and target indicators. Down the starboard side to the main door, static vent plugs removed. Inside now. How many times have I felt my way up and down the fuselage with eyes tightly closed so that I could locate every component in the dark? I had to be able to find every fire axe, extinguisher, field dressing and the morphia, portable oxygen bottle, intercom, and oxygen connections. As well as being able to put my hand on every hydraulic, pneumatic and electrical component, know what it did, how it worked, and what in-flight repairs I could carry out. I would also check fuel contents and oxygen supply. These careful checks were meticulously carried out prior to every flight. It was the drill and the ground crew accepted that it did not reflect on their efficiency.

I rejoin the crew outside. There is nothing to do now but wait, and still forty minutes to go before we climb aboard. We smoke one cigarette after another. Everyone wants to be off and to get the job done. We all want to be able to do something, anything, but wait. The airfield is strangely silent, save for the feint whining of a three-ton truck on the perimeter track over a mile away. A rook can be heard crowing in a distant copse.

A car turns into the dispersal and pulls up under the wing. The Wing Commander alights and has a word with the pilot. Satisfied that all is well he wishes us good luck and drives on to the next dispersal. At intervals other cars arrive with the section leaders, each checking that there are no snags. Then the Padre and Medical Officer arrive. The M/O offers us caffeine and airsickness capsules. And all the time the butterflies in the stomach keep up their constant flutter.

Ten minutes to go and time for the rear gunner to get into his turret. With so much bulky clothing he needs help to get in, so one of us pushes him in on his back feet first. We stand outside his turret talking to him through the clear-vision panel.

A few stutters then a steady roar follow the distant whine of a starter motor as an aircraft begins to start up. The pilot checks his watch and says, “time to go”. We say “see you later” to the rear gunner and make our way to the main door, throw in our gear, and climb the ladder in turn, the last man aboard stowing the ladder and securing the door.

There follows the uphill walk to the cockpit, leaning forward against the angle of the floor. Then the overpowering petrol fumes as we climb over the main spar in the centre section. On reaching our seats the pilot and I continue our checks. Flying controls free and working full range, undercarriage warning lights showing green. Brake pressure ok. Propeller pitch, fully fine. Number two fuel tanks on. Radiator flaps to override, superchargers in moderate gear.

The ground crew has appeared, two men climbing precariously up the undercarriage struts into the nacelles where the Ki-gas pumps are situated. With the pilot operating the ignition switches and starter buttons, and myself the slow running idle cut-off switches and throttle levers we start the engines in sequence from port outer to starboard outer. Trolley acc’ plug disconnected and jettisoned, ground flight switch to flight. A short period with engines at 1200 revs to allow them to warm up, then run up each in turn to full power, checking rpm, boost pressure setting and magneto levels. I select bomb-doors closed, a last look around the cockpit instruments and “ok, chocks away”.

13

[page break]

On receiving the hand signal a man on each side of the aircraft runs forward to drag away the heavy wooden chocks at the end of their ropes. With a hiss of released brakes and a burst of power from the engines we are guided out of the dispersal to join the squadron, the ground crew turning their backs to the gale of dust and flying debris.

A squadron of Lancaster’s taxing out to take off is an impressive sight. Each aircraft weighing twenty-eight tons they move round the perimeter track, nose to tail, like great ducks. With up to a hundred Merlin engines roaring and breaks [sic] hissing and squealing they taxi past at up to 30mph. The noise laden air vibrates against the face and the ground trembles.

A small farm cottage on the edge of the airfield is occupied by a young married couple who always stand at their garden gate with a child in their arms as we go by. All the crews return the little girl’s wave, the gunners raising and lowering their guns. Over fifty years later I can still see that little face, surrounded by light curls, laughing, in spite of the noise and clamour.

As we pass the flying control tower, with the silent watching figures on the surrounding balcony, we glimpse the duty controller whose voice we hear over the radio.

I apply twenty-five degrees of flap, then, close the jettison valves and all balance cocks. Elevator trim two degrees nose heavy.

We join the queue at the end of the runway, moving up like cars in a traffic jam as aircraft take off. A burst of power to the engines, now and then, to prevent the plugs oiling up on the rich fuel mixture. A close watch on the temperature, as the engines quickly overheat at idle revs.

The butterflies in the stomach are beginning to subside now there is something to occupy the mind.

The aircraft in front of us is well down the runway as we turn onto the threshold, line up and come to a stop. The green Aldis signal light, at the chequered caravan, dazzles as the final checks are completed. Fuel boost pumps on. Barometric pressure set on the altimeter. Engine temperature and pressure ok. Radiator flaps to automatic. Compasses set to runway bearing. Cockpit windows closed.

The pilot settles himself comfortably in his seat and says, “right, all set” and opens the throttles to 2,000 revs. The cockpit becomes a vibrating Bedlam of noise, the aircraft straining against the brakes. From the corner of my eye I glimpse the fluttering white hankies of the off duty WAAFs who always assemble to wave each aircraft off.

With a sharp hiss the brakes are off, and we begin to roll forward. Steadily the pilot advances the throttles, jiggling them to keep the nose straight. The nose dips as the tail comes up, revealing the runway lights tapering almost to a point 2,000 yards ahead. “They are yours,” says the pilot, who now has rudder control, and I take over the throttle levers. Smoothly up through the gate and on to full power, 3,000 revs and 12lbs. boost. The noise of the four Merlin’s at full power is deafening and normal speech is impossible, even shouting through cupped hands directly into an ear is useless. The rumble of the wheels, felt rather than heard, is added to the world of noise. Halfway down the runway, and the gap between the two end runway lights grows at an alarming rate. 80 knots, then 90. The wheel rumble fades slightly as the wings begin to flex on the increasing cushion of air, the tyres skipping in long hops. 105 knots. The pilot crouches forward in concentration, eases the stick back and with a final bounce we are airborne. The runway lights flash by thirty feet below and we are clear of the boundary hedge. I lift the undercarriage selection levers and as the wheels start to retract two reds replace the two green lights on the indicator. With a slight clunck [sic] the wheels are up and the two reds wink out.

14

[page break]

Speed builds quickly as the pilot holds the nose down. At 165 knots he asks for climbing power and I adjust pitch and throttle levers to give 2,600 revs plus 6lbs boost as we climb away into the growing dusk. At 5,000 feet I lift flaps, the pilot correcting trim as the nose drops.

After the exhilaration of take-off the necessary chatter, over the intercom, dies away and everyone settles down to their individual routines.

I start to fill in my log, a time consuming process with the engine and aircraft details to record. With a full fuel load of 2,154 gallons, an engineer’s calculations must be accurate to within ten gallons; checked against remaining fuel on return to base. Gauges are only used to check for leaks.

After setting course on time over base we cross the coast at Cromer on the shoulder of Norfolk, still climbing. The gunners test their guns into the sea and after a short stuttering burst the smell of cordite wafts into the fuselage.

At ten thousand feet I turn on the oxygen supply. There is a chill in the air now as the temperature continues to fall. At near freezing on the ground it will be about minus twenty-five degrees at 18,000 feet.

Boost pressure and the rate of climb begin to fall off and I reach out to select full supercharge. There is a distinct clunck from all four engines as the higher gear is engaged and with the renewed surge of power we continue to climb.

“We’ll be crossing the enemy coast in three minutes” reports the navigator, and ten miles ahead there’s the reception committee. When we reach that position the pretty red twinkles in the sky will be flashes and explosions, near misses heard above the constant roar of the engines. The blast buffeting the aircraft and sending shell splinters through the thin skin of wings and fuselage.

We begin to weave and stars trace a figure of eight above the cockpit canopy. It’s like being on a big dipper and will continue until we cross the coast on our way home. The coastal flak is left behind and on reaching optimal height I reset revs and boost to cruising power, each engine reducing its fuel consumption to about forty-three gallons an hour.

Apart from the stars and the green glow of the instruments the night is black. The pilot, sat inches from my left shoulder is just a dark shadow. Our eyes straining to see the elusive faint blur that will indicate the presence of another aircraft. If it can be seen it is too close for safety and will have to be watched continuously to avoid collision. We’ll move away if it is ahead of us, many gunners open fire at anything creeping up astern of them, friend or foe.

Suspended three and a half miles above the earth it is possible to fly to Berlin and back without seeing another aircraft or feeling their slipstreams, although there could be several hundred in the stream. Another time the sky would be full of them.

To starboard and ahead a line of fighter flares light up the sky with a misty yellow glow, like someone running along a corridor switching lights on as they go. Immediately the guns are trained to port, the dark side, from where the attack will come. We drone forever along the wall of light, silhouetted, waiting for the hail of tracer. As we pass the last flare darkness closes in again, but the fighters are still with us.

Far ahead a green flare bursts and hangs in the sky, red stars dripping from it at six[1]second intervals. Placed by leading pathfinders the flare marks an accurate turning point for the main force. Ten minutes on the final leg from this point will bring them to the target area. The navigator confirms its accuracy as we round it.

16

[page break]

I check the engine instruments and fuel status. Nothing can be seen ahead, everything is black, and the navigator starts the countdown to “H” hour.

The bomb aimer turns his bombsight on, ensures the bombs are fused, and checks the selector and distribution boards. He feeds the necessary information into the bombsights ‘magic box’ and checks the responses to various settings. Dead on time the Blind Illuminators release their flares, row on row, as if each one is placed on the squares on a chessboard. A great floating carpet of light exposes the ground far below.

Still no defences to be seen, but they will be there loaded and aimed. Lying low and not giving anything away until they know we are certain of our position.

The Primary Markers will be making their run-in now, their bomb aimers searching for the aiming point. The target indicator bursts, releasing its contents which form a giant Christmas tree of the most brilliant red as they fall. A second pass as the Master Bomber closely circles the indicator to assess its accuracy. Finally over the RT comes his verdict “hello tonnage, the reds are ok, bomb the reds”. The complete marking process has taken about three minutes from the first illuminator flare being dropped to permission to bomb. Almost immediately the leading main force aircraft are over and sticks of high explosive and incendiary bombs are falling across the target.

By now the defences have opened fire and the sky directly ahead has become a wall of bursting shells and weaving searchlights.

We enter the flak barrage and the familiar sound of shell splinters ripping through the fuselage can be heard.

Two hundred feet below us an aircraft, with a wing on fire, lazily turns over and goes into a spin. Its crew will be fighting for their lives against the centrifugal force pinning them in their seats. No parachutes appear. We look away as they hurtle to earth and a sure end. Who were they, did we know them. Will we be next?

The target is now a bubbling carpet of fires and bursting bombs. From below light flak is coming up in a trelliswork of slow graceful curves; string upon string of balls of coloured light, deceptively beautiful until they reach you and flash by like the most deadly lightening.

Above and ahead an aircraft is caught in the intersection of three blinding searchlight beams, twisting, turning and diving as it’s clobbered by its own personal barrage.

The flak gets more intense as we get nearer the aiming point. The bomb aimer crouches over the bombsight to assess the rate at which we are approaching the target. Start the run too early and we are vulnerable in straight level flight for longer than necessary.

As the bomb doors are opened the aircraft stops weaving and begins to shudder as the slipstream enters the bomb bay and batters at the doors. The aiming point appears half way down the long arm of the graticule and the primary red indicator is burning itself out and beginning to fade. The bomb aimer can be heard over the intercom guiding the pilot onto the target; “left, left steady, right, steady, steady”. The aiming point creeps agonisingly along the graticule to the cross section. “Now”, his thumb presses down hard on the release button, “bombs gone”. Each bomb is felt as it leaves the aircraft, and there is an upward surge as the 4,000lb ‘cookie’ goes along with the green target indicator. The bomb aimer will look through the clear vision panel in the front bomb bay bulkhead to check that all our bombs have gone. The bomb doors close as he climbs back to the cockpit.

16

[page break]

We begin to weave again. Some seconds later the voice of the Master Bomber comes over the RT, “bomb the greens”. The knowledge that we have paved the way for hundreds of tons of bombs is pushed to the back of our minds.

After the confines of concentration on the bomb run I become aware again of what is happening around us. The world is a mad man’s worst nightmare of colour, noise and explosions. The photoflashes dropped with each bomb load create a continuous flicker like summer lightening. Undersides of aircraft reflect the red glow of the firestorm more the three miles below. We seem to hang motionless under a ghostly grey dome of light. Light enough to see the bombs in gaping bomb bays, and see them tumble past from higher aircraft. Bursting shells surrounds us, bursting too rapidly to count. The only sign of progress across the target area is the lazy slipping backward of thinning balls of smoke as the flak ceaselessly hammers at us. After what seems an eternity, but in reality about eight minutes, the flak begins to abate and darkness closes in again as the target slowly falls astern.

The pilot calls up each crewmember in turn checking for casualties. I connect a portable oxygen bottle and walk the length of the fuselage checking for damage; Ron the mid-upper gunner complains that the light from my dimmed torch is reflecting on the Perspex of his turret and attracting night fighters. I reply that if there is a hole in the floor I want to see it before I drop through. On the next op’ he’ll make the same complaint and I will give the same reply, it has become a ritual performed every time we leave the target area.

Regaining my seat I reset engine power to lower our airspeed to 155 knots. This will increase the flying time of our homeward journey but will economise on fuel at our reduced weight.

I soon begin to feel hungry but know if I eat the sickly-sweet Fry’s Chocolate Cream bar I’ll bring it up again in minutes. The small tins of orange or tomato juice are frozen solid; it’s probably just as well with the constant weaving. I will resort to sucking one of the barley sugar sweets I keep in my pocket to get some saliva back into my dry mouth and throat. What would I do for a cigarette?

A burst of tracer stitches its way across the darkness a short distance away on the starboard beam. Seconds later a twinkling star, level with our wingtip, gets bigger and longer like a comet. Some one’s luck has just run out. The small comet becomes a wild blaze and begins to curve downwards, followed by a plume of red as it hits the ground.

Our eyes feel tired and gritty as we peer into the night, the journey endless. There follows hour after hour with no sensation of speed or progress, broken up by taking regular sextant shots from the astrodome for the navigator, and doing constant calculations of fuel consumption to relieve the monotony. In the back of all our minds is the thought that an unseen fighter may have our blip on his radar screen and is creeping up on us from behind and below.

“The coast is coming up,” says the navigator “we can start letting down now”. I reduce the engine power and the altimeter starts to unwind. There is a faint horizon to the east but we will be safely over the sea when day breaks. Below 10,000 feet I turn off the oxygen supply and unclip my mask, which has been chafing for hours. We weave through the coastal flak belt and a measure of safety is reached, skimming at fifty feet above the grey heaving mass of the North Sea.

A line of cliffs appear on the horizon and with a nod the pilot eases the stick back and we clear the cliff top with feet to spare.

17

[page break]

Almost dead ahead, in the early morning light, a solitary figure follows a horse and harrow. Hearing our approach he moves to the horses head to take the bridle, the horse stamping its forelegs and flinging its head high. As we hammer past at little more than hedge height the figure raises an arm. Is it a friendly wave or a clenched fist on behalf of the terrified horse? We will never know, nor will we know how many times he has done that this morning as hundreds of aircraft follow the same track home.

The horizon tilts as we turn onto the final course for base, gain a little height, and the spire of All Saints church, Longstanton, begins to come into view. We join the circuit at 1,200 feet and request permission to land. From the control tower the friendly voice of the duty controller is clear, “hello, O-oboe, you are clear to pancake, runway 040, wind 026, 7 knots”.

On the up wind leg. Pitch fully fine, 25° of flap, fuel boost pumps on, brake pressure ok. We reduce speed and altitude as we turn to port on the cross wind leg. Downwind now, and an airspeed of 135 knots. Wheels down and the two red lights appear on the indicator panel, to be replaced by two greens as the undercarriage locks down. As we enter the funnel at 800 feet, the runway stretching out ahead and below; my stomach registering the rate of descent. At 500 feet the pilot applies full flap and I begin to call out the airspeed and altitude. We cross the boundary hedge at 10 feet and 110 knots. The pilot checks back on the stick to round out as I pull the throttle levers right back to the stops. With a scream and two puffs of smoke from the tyres we are down and rumbling along the runway, the engines popping and muttering quietly until I return them to idle speed as we clear the runway.

We taxi to the dispersal point and the waiting ground crew guides us into position, and with the chocks in place the pilot and I go through the shut- down procedure. As the last propeller comes to a jerky stop a deathly silence descends. We push our flying helmets back off our heads and sit for a few seconds listening to the faint whine of the instrument gyros slowing down. There is a feeling of great weariness, of being totally drained.

The rest of the crew is already out of the aircraft; we join them and light a cigarette, the first drag harsh to the dry throat. Our legs and inner ears trying to adapt to the firm ground again. One of the ground crew, at my shoulder, enquires about damage. He seems to be speaking from twenty feet away, his voice weak and distant after the roar of the last seven hours.

Transport arrives, and after leaving our gear at the locker room we carry on for interrogation. Just inside the room is a smiling WAAF dispensing strong sweet tea, from a large urn; and beside her the padre with a large box of cigarettes and a bottle of rum with which to top up our mugs. While waiting for a table to be vacated I take the opportunity to complete my log by calculating the air and track miles per gallon of fuel. I arrive at the figure 0.9mpg. We occupy a table as a crew leaves and the intelligence officer reaches for a fresh report sheet. We go through the trip from take-off to landing. He needs to record our timing, bombing accuracy and concentration. Enemy defences and fighter opposition. Times and positions of aircraft we witnessed go down. When we can tell him no more we leave and walk slowly to the mess for a meal.

I remember the fresh smell of damp earth and mown grass and the chill breeze on my face after the hours of wearing a stuffy oxygen mask.

In the mess the cheery WAAF’s behind the serving hatch ask us if we had a good trip, we would reply “yes thanks, piece of cake”. If you came back it was always a piece of cake.

18

[page break]

Breakfast was two slices of Spam, a fried egg and lots of dry bread. I always had to force my breakfast down. All I wanted to do was sleep, but I knew that once in bed I wouldn’t be able to for some time. I would lay there unwinding, listening to everyone else restlessly tossing and turning. When sleep did come it wasn’t a gentle drifting away but a sudden cutting off of thoughts and feelings, like a door slamming shut.

Later that same morning, at the Flight Office, we would learn that we were on that night’s order of battle and the butterflies in the stomach would begin their fluttering all over again.

And so it went on Dortmund, Rennes, Aachen, Berlin, Lille, Duisburg, Amien, Hamburg, Kiel, Stuttgart, Emden and many, many more.

[photograph]

I have a vivid memory of our last operation, on September 10th 1944. We had returned from an attack on German positions at Le Havre at 7am, and were on the order of battle to go again that afternoon. Just before take-off we were informed that this was to be our final op’ and we were being stood down.

On our return we approached base in a long shallow dive to beat up the airfield. At 200 knots we thundered along the runway at zero feet to pull up hard at the far end, the g forces pulling down the flesh of our cheeks and the lower lids from our eyes. This manoeuvre was strictly forbidden; but surely everyone must have felt on return from their last op’ the same jubilation and relief as the tension fell away. We had been a crew for a year, had flown 450 hours together and completed 64 operations without a rest period. We had done it, beaten the odds, and joined an exclusive club.

After landing, and a mild rebuke from the tower who must have understood, the grins on the faces of the ground crew were as broad as our own. Our backs were pounded until they were sore; few crews survived that many missions together.

19

[page break]

We celebrated that night with the ground crew at The Hoops Inn at Longstanton. The night was at our expense as a token of our appreciation. It was well worth the two days of hangover.

We had flown Op’s all Summer. I seem to remember many crews adopting a diet of beer, cherries and strawberries, the latter cadged from the land-girl’s at Chiver’s orchards at Histon. This was also the time of the great beer shortage, the only time in the history of England when crews were drinking it faster than it could be brewed. When not flying of course.

These were the days and times of such as Jonnie Denis, James Frazer-Barron, Alan Craig, Brian Frow, Tubby Baker, Ted Pearmaine, Eddie Edwards, Robbie Roberts, Brian Foster, Gerry South, Flash McCullough and so on. Remarkable days and remarkable men, I wonder what became of them.

Great times we had together. We were like brothers sharing our last cigarette or sixpence. Off duty rank meant nothing and we were all on first name terms, but we all knew where to draw the line between respect and over familiarity. Life was one big round of merriment, pranks and youthful high spirits; but once aboard the aircraft we were as sober as judges. Drills and checks were carried out to the letter and nothing ever left to chance. At no time was there idle chatter over the intercom, not even when we were flying for pleasure.

[photograph]

High spirits

Op’s were never discussed at any time during the twelve months we flew together. After an op’ we came out of the interrogation room and that mission was never talked about again, ever. What was there to say? They were all the same, the noise, the fighters, and the flak; and always the cold.

As I sit here, fifty years on, I can remember events clearly but can’t put the name of the target to them; and yet others spring to mind straight away.

Normally the navigator sees nothing outside the aircraft from take-off to landing. On our first German target the pilot called him forward to see what a target looked like. He stood in the cockpit for a few seconds then raised his eyes to the sky in front of us. His only words were “bloody hell”! And my reaction? I distinctly remember thinking, ridiculously; “they are trying to kill us”.

20

[page break]

On one Berlin trip we were forced down by ice from 19,000 feet to 8,000 feet. We had to throw out all the ammunition and any non-essential items to try and lighten the aircraft. Waiting for the order to abandon aircraft, I remember clearly saying quietly “don’t cry Mom when you get the telegram”. Luckily we ran out of the icing area at 8,500 feet and managed to get back to base so late that they had given up on us. I don’t know what I would have said to the crew if my microphone had been switched on at that particular time. I think that was the closest we ever got to meeting our maker.

I think we had been to Berlin when we had to land at the first airfield we came to on the way back. The three engines still running had cut out through lack of fuel ten feet above the runway coming in to West Malling. The aircraft landed very heavily, the undercarriage gave way and we slid along the runway causing serious damage. With our bumps and bruises, we had to return to Mildenhall by train via London. We got some very odd looks in London and on the train as the only clothes we had was our flying gear.

I later discovered that this 746 aircraft Op’ was the last in which Stirlings (which we were flying) were used over Germany.

Leaving Karlsruhe we were attacked by night fighters and during the twisting and turning of evasive action the navigator lost our precise position. After flying on a rough course for some time he found out where we were when we flew alone over Strasbourg and into a heavy barrage of accurate predicted flak. The next morning we went out to the aircraft, and starting at the tail, counted eighty-seven holes between the rear and the mid[1]upper turret before we decided to stop counting. The rest of the aircraft and wings were equally peppered with jagged holes. We had used up a little more luck from our reserve.

I recall one occasion returning from a daylight op’ with a full bomb load and bouncing badly on landing. “Round again” shouted the pilot and I opened the throttles to full power. We roared across the grass at an angle to the runway directly toward the Longstanton church. The pilot coaxed every inch of height from the aircraft as the church loomed closer every second and flashed beneath us with inches to spare. Looking down I saw the villagers scattering. A child standing in the lane staring up at us screaming with fright at our sudden appearance and deafening noise. A woman wearing an apron, running to scoop up the child in her bare arms and racing to safety. Farm animals stampeding in the nearby fields. It all registered on the mind in the second or two we were over the village. After landing the rear gunner said, jokingly, that if we had warned him he could have leaned out of his turret and removed the steeples weather vane as a souvenir.

We once endured the long weary drag of nine hours to Stettin, in Poland. The navigator recording, over the target, an air temperature of minus forty-nine degrees. The inside of our aircraft feeling little warmer. That night must have been the coldest of my life.

We were half heartedly shot at over Sweden. As Sweden was a neutral country it had no need for the blackout suffered by Europe and so I saw for the first time an illuminated city from the air. It looked like a giant dew covered spiders web.

We were coned by searchlights several times and came back with the scars to prove it, the shell splinter holes and the night fighters trade marks.

On a raid to Stuttgart the main door lock broke and the door opened over Germany. It was eventually closed and secured with parachute cord. On return to base we discovered that a couple of incendiaries had failed to release over the target, but as soon as the bomb doors were opened they fell out and immediately burst into flames directly under the aircraft. Our mad scramble to get out of the aircraft was slowed somewhat by the knots in the cord securing the door. The ground crew were quick to push the aircraft away from the fire.

21

[page break]

Another engineer once told me that we were known as the lucky crew, usually last back and rarely on more than three engines. As a marker crew we occasionally had to fly over a target a second time to re-mark it. Fred Phillips was the Deputy Master Bomber on about fifteen sorties, and Master Bomber on three. This meant we had to stay over the target for up to twenty minutes as he directed the raid giving instructions to markers and main force over the radio, this could be picked up by the Nazi direction finding equipment which could then set the night fighters onto us. This was always a very risky time. It helped to be lucky and we seemed to have had more than our fare [sic] share.

A few days after our last op’ we were posted to RAF Backla on the shores of the Moray Firth, from where we were posted our separate ways. We wished each other luck, shook hands and parted, never to meet again.

[photograph]

“The Lucky Crew” RAF Oakington September 1944

Never to meet again.

In late November ’44 I was posted to RAF Nutts Corner, near Belfast. 1332 Heavy Conversion Unit, Transport Command was stationed there and I took a course on York C1 aircraft. Back to the classroom again. After passing the ground school exams I was told that I was to join the permanent staff back on Stirling’s. It appeared that a Stirling had taken off on an exercise and completely vanished with its crew. My operational experience on Stirling’s made me the obvious choice as a replacement engineer. My hopes of travelling the world vanished at the stroke of a pen; I simply had to do as I was ordered.

My new duties were to fly as engineer with a pilot instructor and student pilot who was converting from other types of aircraft, many of them flying boats that didn’t have an undercarriage. A lot of the student pilots were foreign. They were all very enthusiastic and

22

[page break]

eager to convert to Stirling’s, their occasional over enthusiasm and language difficulties made for an interesting time. It was disconcerting to be on the final approach with wheels up and red flares going up like a firework display from the caravan on the threshold. On touching the pilots arm and pointing to the undercarriage selector lever he would grin happily and give a thumbs-up sign, quite prepared to continue his approach and execute the perfect belly landing. The only course of action was for me to open the throttles wide and force an overshoot, then try and impress on him the error of his ways.

My nights and weekends were spent in Belfast with “Tommy” Thompson, “Mac” MacDonald and Roy Baker visiting the Four Hundred Club and the Grand Central Hotel.

Mr and Mrs Cree of Cliftonville Circus invited me to spend Christmas ’44 with them; I was treated like a member of their family. A wonderful thing to do for a lad so far from home at Christmas.

I remember watching an incident involving my pal Roy Baker. A Stirling was coming in to land when a tyre burst, the undercarriage collapsed as the aircraft went into a ground loop at over 100 knots. When it came to a halt all the crew emerged from various escape hatches except Roy, the engineer. He was still inside diligently carrying out his emergency drill, turning fuel cocks off, electric’s off, closing engine cooling grills etc. He finally emerged with a self-satisfied look on his face, then realised that both wings had been torn off, complete with engines and fuel tanks, and were at least quarter of a mile away. He was cheered when he later entered the mess.

Nothing ever eclipsed the beauty of Northern Ireland from the air, with it’s patchwork of fields of brown and straw yellow and the most brilliant green, it looked truly beautiful.

A few weeks later the unit moved to RAF Riccall, just south of York. The ageing Stirling’s were taken out of service and replaced with, American built, Consolidated Liberators. These were the last aircraft I flew in as engineer. I was taken off flying duties and made Adjutant of the Flight Engineers Ground School. Of my service in the Royal Air Force this was the job I had least enthusiasm for, sitting behind a deck [sic].

[photograph]

Tom & Ivy Jones 1946

Whilst at Riccall I met Ivy Ridsdale, a Yorkshire lass, at Christie’s Dance Hall in Selby. We would be married in February ’46

In November the unit moved to RAF Dishforth, which meant a seventy mile round trip on a bicycle to visit Ivy at her home in Hambleton, near Selby.

23

[page break]

After an interview at Group Headquarters in York I received my final posting to RAF Bramcote. On arrival I was made Station Armaments Officer. Another desk job.

Eventually I was sent to RAF Uxbridge. After a brief medical and signing a few papers I stood holding a cardboard box containing a suit and hat. My four years service with the RAF Volunteer Reserve was at an end. I have never regretted it. I learned a lot and did things I would never have had the opportunity to do in civilian life. Overall, I enjoyed it thoroughly. I have not met again or heard from any of the crew I flew with on Op.’s, perhaps none of them survived the rest of the war. I would love to know if they did, but to meet them again? I think not. I didn’t fly with a group of men in the autumn of their years; they must remain young as I remember them then. Besides, time and people change, we might not even like each other now.

At briefings the aiming point had always been designated as factories, oil installations, docks, railway yards and the like. Residential areas near the targets were never mentioned, but they were there; and the thousands of people who lived in them. The fact that we were personally responsible for the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians has lived with us all our lives.

Some unfortunates, through no fault of their own, reached the point where they could no longer carry on. Irrespective of how many Op.’s they had completed they were deemed lacking in moral fibre. I never knew or heard of any member of aircrew that had anything but sympathy to them.

I remember some of the lads who had a tough time. The empty sleeves, and trouser legs of the amputees. There were lads with no faces. Noses and ears no more than shrivelled buttons, and heavy newly grafted eyelids. Their mouths little more than a slit in a face rebuilt with shining tightly stretched skin grafts. Some had hands shrivelled and clawed like eagle’s talons. They sought no sympathy or favours but carried on doing a job they could manage. When they went drinking with us their laughter was as hearty as ever, their spirit unbroken and no sign of bitterness.

I have tried to put to the back of my mind the countless times I saw aircraft shot down and the lives of their young crew snuffed out in agonising seconds. But try as I might the images remain as graphic as if it only happened last year.

As a crew we were detailed to attend the burials of crew that had got back to base, only to crash on landing. A cruel fate, so near yet so far. After the service in the village cemetery, we saluted each open grave in turn. I cannot count the number of times we did this.

What made us do it time after time? Was it patriotism? Was it the pride in volunteering being greater than the butterflies in the stomach? Was it the fear of letting down the crew, or of the life long stigma of lacking in moral fibre? Perhaps it was one or all of these. Who knows? And what do I have to show for it? My discharge papers and identity discs, my flying log book, a few medal ribbons and a thousand memories.

24

[page break]

[photograph]

Letter from George VI

[photograph]

Tom and Ivy Jones 2002 and Distinguished Flying Cross

[photograph]

Thomas John Jones DFC

April 19th 1921 – January 28th 2004

Epilogue

My sweet short life is over, my eyes no longer see,

No country walks, or Christmas trees, no pretty girls for me,

I’ve got the chop, I’ve had it, my nightly op’s are done.

But in a hundred years I’ll still be twenty-one.

R. W. Gilbert

One of Dad’s favourite poems.

25

[page break]

Decorations

24/12/43 PHILLIPS, Frederick Augustus, PO (Aus409939) RAAF 622sqn This officer has taken part in several sorties and has displayed a high degree of skill and determination. One night in Nov 1943, he piloted an aircraft detailed to attack Ludwigshafen. Whilst over the target area his aircraft was hit by shrapnel. The petrol tanks were damaged and the petrol supply could not be regulated. Nevertheless, PO Phillips by skilfully using the engines, flew the aircraft back to this country. Some nights later, whilst over Berlin, one engine of his aircraft became u/s. On return flight considerable hight [sic] was lost and ammunition was jettisoned in an effort to lighten the aircraft.. In the face of heavy odds, PO Phillips succeeded in reaching base. This officer has displayed great keenness and devotion to duty.

Awarded DFC.

14/11/44 PHILLIPS, Frederick Augustus. Flt Lt (Aus409939) RAAF 7sqn Flight Lieutenant Phillips has a splendid record of operations. At all times he has set a fine example of leadership, coolness and unfailing devotion to duty which has been a source of inspiration to the squadron.

This officer has consistently displayed fine flying spirit and cheerful determination in the face of the most adverse circumstances.

Awarder Bar to the DFC Lon Gaz 14/11/44

14/11/44 NAYLOR, Joseph William 1817796 Flight Sergeant, No 7 sqn Air Gunner.

FS Naylor has completed 53 operational sorties, including 44 with the Pathfinder Force of which 34 have been as marker. This NCO is a rear gunner in a marker crew which has carried out extremely successful day and night sorties with this squadron and has proved himself to be an exceptionally good aircrew member. Throughout his career, he has shown courage and tenacity of a high order and in the face of danger has displayed outstanding fearlessness.

Awarded DFM Lon Gaz 14/11/44

Flt. Lt. GOODWIN, David Graham, Lon Gaz 14/11/44 awarded DFC

F.O JONES, Thomas John, Lon Gaz 12/12/44 awarded DFC

F.O. THURSTON, Harry Clive Edgar, Lon Gaz 14/11/44 awarded DFC

F.O. WILLIAMSON Stanley, Lon Gaz 14/11/44 awarded DFC

P.O. WYNNE, Ronald, Lon Gaz 12/12/44 awarded DFC

26

[page break]

I can’t actually put a time or place on my earliest recollection of my father; I do have a lot of pleasant early memories. Cycle rides with me sitting on a seat on Dad’s crossbar. Trips on steam trains to see my Nan in Birmingham, which would include a visit to Dudley zoo. Days out in York with a look in Precious’s toy shop, which usually resulted in a new car or truck to add to my ever growing collection.

I recall that Dad was always at work. When I was small he worked as an engineer at Rostron’s Paper Mill in Selby. There he regularly worked six and a half days a week, cycling to work in all weathers.

He always had time for me though, and would spend hours with me reading the likes of Treasure Island, Gulliver’s Travels, Moby Dick and Black Beauty. He would also make me things, like my railway layout with its tunnels and buildings.

When I went to school, he would help me with my homework. I can still remember all about the Kenyan coffee trade, thanks to him. He also sent [sic] hours, in vain, trying to teach me to draw, sadly his artistic genes where ]sic] not passed down to me.

He had endless patience, and would never ever cut corners on any job or project he tackled. Maybe that was thanks to his RAF training.

He was a very skilled engineer and model maker, producing scale working models of stationary steam engines and balsa wood models of aircraft. His last project was of a Hawker Hurricane, with a three foot wingspan, which he gave to the boy who lived next door.

[photograph]

Fully working twin cylinder stationary steam engine made by Dad in the 1970s

27

[page break]

When he retired he turned his hand to art producing many beautifully detailed sketches and water colours.

[drawing]

Lioness, sketched by Dad in May 1979

One of his other passions, after he retired, was taking long walks with his dog accompanied by his three friends. My Mother used to refer to them as “Last of the Summer Wine” after the TV program of the same name.

Dad was a very generous man. My mother told me an amusing story of Dad buying her two bunches of flowers, but only giving her one bunch. It transpired that he had gone into the local chemists, where the girl behind the counter had commented how pretty the flowers were. So Dad being Dad, gave her one of the bunches.

Dad’s health started to decline when he was in his late seventies, which curtailed his walks, but he remained active at home, spending hours in his shed.

Sadly he died on the very snowy night of January 28th 2004 from lung cancer.

There are so many things I wish I had said to him when he was alive, and now so many questions I would like to ask.

And what of the other crew members?