Interview with Alun Emlyn-Jones

Title

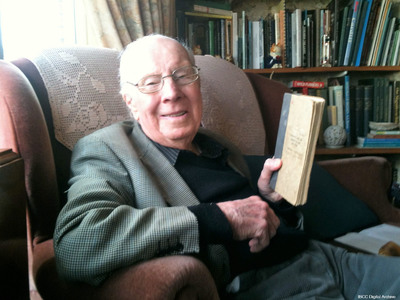

Interview with Alun Emlyn-Jones

Description

Alun Emlyn-Jones (known as Grem among his RAF colleagues) was raised in Cardiff and attended boarding schools in Oxfordshire. He was working at an office supplies manufacturer when he volunteered to serve in Bomber Command, hoping to avoid being called up to the infantry. Alun trained in Penarth and in East London, South Africa, and then worked as a bomb aimer. Alun talks of flying on the Anson and Whitley, and of being assigned to a Halifax crew. He describes a training flight accident at Garrowby Hill, Yorkshire in which his crewmates were killed. Alun, who was hospitalised at the time, was not on board the aircraft. He recalls his loneliness at being without a crew, and the unexplained animosity towards him from a senior officer. He talks of joining another aircrew and of adaptability being a part of the role of the bomb aimer, before reflecting on his feelings about the unjust dismissal of the crew’s pilot for lack of moral fibre. Alun recalls his transfer to RAF Transport Command in 1945 and talks of organising the erection of a memorial to his crew at Garrowby Hill. He mentions his pride at the memorial, and his attendance at annual commemorations there for many years. He goes on to reflect on his preference for the Halifax over other aircraft, his enjoyment of flying, and on the great friendship and comradeship among aircrews, describing a closeness which continued after the war. He also mentions his affection for the animals that he kept in his billet during the war. Alun recalls that he first returned to his pre-war job after the war, but later joined the Welsh Council on Alcoholism to help others and in support of his sister, whom he describes affectionately.

Creator

Date

2016-10-12

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

00:34:11 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AEmlynJonesA161012, PEmlynJonesA1601

Transcription

This interview is being conducted for the International Bomber Command Centre. The interviewer is Anne Roberts, the interviewee is Alun Emlyn-Jones. The interview is taking place at Mr Emlyn-Jones’s home in Cardiff, in Wales on the 12th of October 2016.

AR: Thank you Alun for agreeing to talk to me today.

AEJ: My pleasure.

AR: Also present at the interview is Julie Emlyn-Jones, Alun’s wife.

AEJ: That’s right.

AR: So Alun, could you tell me something about your early life?

AEJ: My early life? Well I was brought up in Cardiff, my parents - I was one of two children, my sister was six years older than me and I was the second one and I spent all my early life here really. Then at the age of ten I was sent away to school, I was banished to England for my education. I was very unhappy at school, it was a very difficult time for me, it was just emotional. I was a home boy, I wanted to stay at home I didn’t really want to go but I went to Summer Fields in Oxford to start with and that’s in my book under the title ‘Nightmare’ [laughing] and then I went on to Charterhouse, which was easier. And then, heaven knows what might have happened, I might have gone on to university and so on I suppose, but as a matter of fact I don’t think I was all that scholastically brilliant because I wasn’t working as much as I should have, but the war came to make my decision for me. So I was able then, my parents let me come home waiting for whatever should happen. When it came to, as you know if you volunteered, even if for a short while before you would have been called up you got the privilege of putting down preferences of where you would go, and I must say I wasn’t directed by anything more noble than the fact that I didn’t really want to slog through muddy trenches, so I decided on, you had to put one for each service. So I put my priority as aircrew in Bomber Command, my second one was the submarines and my one for the Army was in tanks, so the idea was that I was going to be carried wherever I was going [laughter] and in due course I was given my first choice and I went to Penarth, I’ve skipped a lot of my youth I’m afraid, went to Penarth to start training there. I’ve skipped a lot, you want to know more about my youth of course.

AR: No, whatever you want to tell us, it’s fine. So your training was in Penarth?

AEJ: We started our initial training, well we started, we met in Penarth before we were sent out to our stations, you know. We went to various places, all over the place. I spent a lot of time training in South Africa, went out on a troop ship, it took six weeks out and six weeks back, incredible, and did my training in a place called East London in South Africa and then came back in due course.

AR: And what did the training entail Alun?

AEJ: Well I suppose we did a lot of flying, Ansons and aircraft like that and then we graduated I think to Whitleys and it was on Whitleys that I was flying with my first crew at the conversion unit. At that point, at the conversion unit we moved to Halifax, the Halifax which we were going to fly during operations. And that’s what we did, so we flew in the Halifax on a regular basis from RAF Rufforth on the flat plain of York and then one day, my crew, well I had my appendix out, that was a very important thing for me. I had an appendix attack. I was able to get home, or it happened somewhere where I could be at home and I had my appendix attack and I had my appendix out in a local nursing home in Cardiff. I wrote to my skipper Stanley Bright ‘I do worry about one thing’ I said, ‘because this has caused me to leave you now and you may not be able to wait for me’. He said ‘don’t worry a bit, the weather’s clamped, we’re doing very little flying, you’re going to be back in a few weeks and that’ll be fine’ And that was the last I heard of him, from him. They were flying from Rufforth on one of their training trips, conversion trips while I had my appendix, they had taken off but they were In, I think, 10/10ths cloud and they were doing simply something like, a simple exercise, I think something like circuits and bumps, you know landing, taking off, landing, taking off, all that sort of thing and I think they got slightly off track in this dense cloud and didn’t realise, because we didn’t have the sophistication with radar that they have now and didn’t realise that the hill, called Garrowby Hill was between them and the ground and they flew into the hill. They killed a passing truck driver and the plane hit the road near Cot Nab Farm, top of Garrowby Hill and disintegrated in the fields and they were all killed. So suddenly I was left, an odd bod with no crew and ah, had to wait to see what would happen. But of course that caused quite a lot of delay in when I started flying and so on as you can see from my logbook, and eventually I was adopted by a crew whose bomb aimer had been taken, borrowed by another crew, and when he was borrowed he was killed. So they ended up as a crew without a bomb aimer and I was a bomb aimer without a crew and they asked me if I would like to join them which of course I was, I was delighted to because that period of just hanging about, just going wandering about the station, not belonging to anybody was a very difficult time, a very, very difficult time. What I couldn’t understand was the attitude of the, I don’t know who he was, one of the senior officers. I couldn’t understand his sort of antagonism to me. He just interviewed me and wanted to know what I was doing and things like that, and then he said ‘get out’. I couldn’t understand that but later, I think I saw that he had been unaware of me not being killed at the time and included me in the list of those who had died that day and I think that he was feeling guilty about that and took it out on me. There was no other reason, I had no personal contact with him that otherwise could have caused that but that made me feel even more isolated really and I just wandered round very lonely and hopeless for quite a while until my new crew adopted me.

AR: And then you flew a number of missions?

AEJ: Well first of all we had a lovely pilot, he was a great guy, Danny and he’d done 13 ops and crashed with a full bomb load. He broke his back and he’d nevertheless come back to flying again and he adopted us and I had great admiration for him, I think we all did. But I of course, as a bomb aimer it was only over the target that I was in charge really and the rest of the time I did odd jobs. I was assistant pilot, I was assistant navigator and all the bits and pieces that went with it, you know helping the wireless operator and anything they could find for an odd job man really. I used to sit next to Danny on take off and as he pulled the heavy aircraft off the ground he would come out in an absolute sweat and I knew he was in pain. After he’d done six or seven ops or whatever it was, one day we were actually out on the dispersal point waiting to take off and he called us together and he said ‘it’s no good I can’t fly, my back is playing up so badly I’ll kill us all’. And I just said to him, because I thought it would be true, ‘don’t worry Danny they’ll understand’. Well they didn’t. The Wing Commander came out in his Hillman and he treated Danny as though Danny was a traitor of some sort. It was dreadful. He said ‘King get into my car’ and then he turned to us and he said ‘I’m sorry your pilot is LMF - lacking in moral fibre’. I thought that was terribly cruel and we asked if we could have an interview with the Wing Commander, which he granted and I was the spokesman and I went in on behalf of the others, with them, and said ‘we want you to know sir that we have great admiration for Flying Officer King and I told him about his broken back, he ought to have known that from the records, and how he’d carried on despite that and how I could see how much pain it gave him when pulling the aircraft back and that in the end he decided that to save us all, he wouldn’t fly. He said ‘your comments are noted gentlemen’ and that was that. Danny was banished from the airfield and we never saw him again.

AR: How did that make you feel, you and your other crew members?

AEJ: Oh very badly about that, very badly. Then my third pilot came into it and took us over and we went on eventually and completed our tour. Well actually they did the full 30 ops and because I had missed one, the one they were on, actually the first one that I’d missed was the Nuremberg trip where we lost more aircraft than any other raid. Because I’d missed that I was officially granted my tour on 29 ops, that was that. That was how that ended and then I got on to Transport Command and so on and I was [emphasis] going to be posted to Japan and that really frightened me. I’d heard such awful stories about prisoners of war in Japan and I thought that was going to be dreadful and I said to then Wing Commander, I don’t know if it was the same one or not, ‘I wonder if I could have a training job of some sort for a while?’. He said ‘you ought to be honoured to be chosen for Japan’. I could have done without the honour. Anyway, the awful thing, but nevertheless, it saved my bacon, what was it, the atom bomb? Yes the atom bomb, because of that the war became over, the war with Japan finished and thankfully for me, I was saved the task of going out there. Then I went on to Transport Command and did various things and I flew quite a lot really but that was the end of my active [unclear]

AR: Where were you in the transport corps Alun?

AEJ: I can’t remember but I’ve got it in my logbook which is there. Yes I’ll have to look it up.

AR: After the war finished, what did you do then?

AEJ: Well, I had been, before the war, before I got called up, working with a little firm called Copy [unclear] Ltd at Treforest Trading Estate, near here, where we made carbon paper and typewriter ribbons. Before the war, as a young man I was pressing green buttons to make a machine go, red buttons to stop it, and things like that and when I came back they said ‘you’d better go in the sales department’, so I spent a lot of time writing sales letters. Which suited me because I like writing so that suited me very well. What was I going to say now, I’ve forgotten.

AR: Well you were talking to me about after the war. Tell me when you did all the work to create a memorial to your crew at Garrowby Hill.

AEJ: Yes, that’s the memorial there. We go up every year. Julie was able to take the service, bless her, as a, what is it for your church, you are a?

JEJ: That’s not part of it.

AEJ: I wanted to say it.

JEJ: I’m an elder.

AEJ: That’s it - I can’t remember things. She’s an elder at the church, so she is able to take the service, which she does wonderfully and we have, very often, and we’re hoping for the same number this time, about 40 people gathered on the hilltop for that occasion. So we do that every year on Armistice Sunday.

AR: And it was you who got the memorial put up?

AEJ: We did, we arranged that, or I did I suppose, well we both did, didn’t we? Yes we both did. We arranged it. We got very friendly with the people who did it, they did a lovely job as you will see. We’ve got the aircraft on the top and it’s a beautiful memorial. They come every time, the people who made it and I think he’s very proud of it and we’re very proud of what he did, it was a great job. That’s what we do every Armistice Sunday. We’ve done, how many? Huge number. A very big number anyway of these, for years and years and years.

AR: And you still keep in touch with - ?

AEJ: It was the seventieth we stopped at, no that was something else wasn’t it?

JEJ: Yes.

AR: And you’ve kept in touch until recently with your old colleagues from the war?

AEJ: I suppose I haven’t really. I’ve lost contact now.

AR: Alan can you tell me about going up to see the memorial and how you feel about Bomber Command being recognised now?

AEJ: Oh very thrilled, very thrilled, yes. Of course we had a lot of fighter boys here and they turned the tables really at that vital moment, but all the boys at St Athans were in fact killed. Every one that we knew, we knew well. My sister was a very attractive girl, and very vivacious, and she had a circle of friends wherever we went and she knew a lot of the pilots. We used to go and stay locally at Porthcawl at the Seabank Hotel and a lot of the pilots from Battle of Britain were there and they all died, sadly. But I think I’m wrong about not having any contact with my crew but my memory, it’s been shot to pieces. [pause] Nobby, Wilf, Geoff Taverner, yes. My bombing leader, Geoff Taverner, he lives in Newport so although we didn’t fly together, he was the bombing leader for my 51 Squadron and I see him quite regularly. He got the DFC actually. And I, incidentally, have just been awarded the medal Chevalier de la Legion D’honneur because quite a lot of my trips were in support of the French and a friend of mine over there, [unclear] Thomas, he said ‘you really ought to apply for the Chevalier Award because I’m sure, knowing your record that you would qualify’. And I did and I was. And Geoff as well, Geoff Taverner. We had a very moving occasion in Cardiff for that. It was rather lovely and the family were able to be there and it was fantastic really.

AR: Congratulations, that’s wonderful.

AEJ: It’s a nice title to have. It’s a wonderful medal, very, very handsome.

AR: That’s lovely to hear. So after the war Alun, life continued and you were working in Cardiff?

AEJ: That’s right and then I got to feel that, it was pure chance really. I wanted to help the people. Because there was a tendency to have a drink problem in my family, on my mother’s side, one of my uncles had a problem and my sister and I both inherited it. And I thought, when I heard about this job, an organisation was being formed in Cardiff, the Council on Alcoholism, if I could get in on that I would be able to help others as well as myself. I applied. My sister, however continued to drink although she was married and she had two children and a loyal husband and she didn’t mean to do these things but she couldn’t stop, you know. She was wonderfully talented, a very gifted and bright girl who drove cars at great speed. She was a tremendous character but she couldn’t quite come to terms with this and I was worried about her and it was because of her, as much as anything, that I thought if I join, if I get in on this job, I’ll learn enough to help her properly and she died the very day I was appointed. But I was appointed, and having put my shoulder to the wheel, as it were, I thought that’s what I’ll continue to do and it became my life’s work. I built up a hostel for people with the problem in Cardiff, Dyfrig House and then moved on and did Emlyn House in Newport. And then we moved on, out into the nearby valleys and did a third one, the Brynnal [?] and then my daughters, two of my four daughters, decided that this was for them so they came in, Rhoda and Lucy and played their very significant role and Lucy became the Director of the Gwent Alcohol Project and Rhoda was in charge of the Community Alcohol and Drugs Team and so we made it a family business [laughter] .

AR: That’s wonderful.

AEJ: I think over the years we were able to help quite a lot of people. The hostel in Cardiff for example, Dyfrig House, we had a Day Centre and a workshop, we had crafts that people could make and all sorts of things as well as having accommodation and support, so there was a lot happening.

AR: Wonderful. Is there anything else Alun you can remember about your - going back to the RAF, your time in Bomber Command, anything else you would like to tell us about what it was like to fly on the Halifaxes?

AEJ: Well I liked the Halifax. The Halifax of course was overshadowed a bit by the Lancaster, in the same way really as the Spitfire outshone the Hurricane. The Hurricane did a very fine job nevertheless and the same applied to the Halifax. It was eclipsed by the glamour of the Lancaster. But I liked it, on a practical basis it had much more room inside so you could move around more easily. Also, which I think is a very important point, it was easier to bail out of [laughter] . It was a good sturdy workhorse and I got very fond of it yes. It just didn’t get the glamour and people always think of Lancasters, they don’t think of Halifaxes. Of course before that, there was the Stirling, after the two-engined ones. I didn’t fly in those, I think I got one trip once but not an operational trip and of course before that we were on Whitleys. We were flying Whitleys. Yes I liked the Halifax very much indeed. I enjoyed flying actually. I mean compared with my friends who are in civilian airlines who drew thousands and thousands and thousands of hours, the whole war I think my total was seven hundred and fifty but seven hundred and fifty hours we packed a lot of stuff into it. I find it such a privilege really to work with crews like that. We became great friends, that’s the thing, it wasn’t just that we were working together, we became great friends. You know we went out together as well and met socially when we could. Oh it was tremendous comradeship. I deem myself very fortunate indeed to have had that opportunity and of course to have survived because the expectation of life was only six weeks, and so to have survived was extraordinary good fortune. We were losing boys all the time. You know, ‘so and so bought it’ that was the expression, ‘so and so bought it’ so you know one of the people we knew well hadn’t come back, they had crashed or been shot down. I mean on one daylight (sortie) I remember seeing lots of aircraft going down. Later, this particular man, lives in Cardiff so I see him quite often because I’ve got a group called 51 Squadron and Friends. The group meets quite regularly and I saw this aircraft just below me, being shot down and it turned out to be his so I was able to tell him I’d actually seen him shot down. He was then captured by the Germans but they treated him with respect. Another of my friends who was shot down in the First War was put into Pfaffenwald which was dreadful and he had a dreadful time there but then the Luftwaffe itself said ‘you shouldn’t have this man there, he should be in a proper prison, so he was transferred, that surely saved his life although he died young in the end, but that was a separate matter. But er, yes there was great comradeship. I’ve rambled on enough I think.

AR: Not at all, it’s been fascinating.

AEJ: Thank you so much.

AR: No thank you, thank you Alun very much for giving us the time.

AEJ: It’s was my pleasure. I just wonder how many things I’ve missed out.

AR: Alun we’re going to carry on now. Can you tell me a little bit about your nickname?

AEJ: Actually of course so many of my compatriots from Wales were called Taffy and I suppose I would have been but in fact Grem fitted in very well and I got called Grem all the way through my Air Force career. That’s because it’s short for Gremlin and Gremlin was the little creature who used to disturb our instruments in the aircraft, imaginary one I need hardly say [laughter] . It was short for that and it also rhymes with my name Emlyn, Alun Emlyn. So for those two reasons I got called Grem and enjoyed that nickname and I’m still called Grem by some people. Geoff Taverner my colleague and one time bombing leader from Newport, he still calls me Grem for example, so it’s very nice to have that.

AR: And animals played an important part for you.

AEJ: Yes, well when we were stationed at one place I picked up a goat, a little goat. He was a dear little thing and he used to live in my billet and used to greet me with licking my face at night and things like that but then he got bigger and bigger and bigger and I had to think of something to do with him so we asked a local farmer if he, no we didn’t, we found a spot at a water tower in the village and he would have shelter and he was on a long lead and we had him there for quite a while and then one time he got away from his lead and went all round the village eating the tops off people’s plants. That became rather unpopular so I gave him to the local farmer on the strict [emphasis] understanding he would be used for breeding and not be killed. So I hope that’s what happened, I hope he had a happy life. Then we had our dog, Jimmy, I picked Jimmy up somehow and Jimmy sort of lived constantly with us and was a great guy. I can’t remember what happened to Jimmy in the end.

AR: Did Jimmy wait for you when you came back from - ?

AEJ: Yes Jimmy used to be there. Wherever we’d been and wherever he’d been in the meantime , he was always waiting on the tarmac when we got back and he lived in my billet with me. So we had a bit of a menagerie really. I can’t remember what happened to Jimmy, pity we can’t ask [laughter]. So there we are and of course when we searched for the spot to put the memorial for the first crew at Garrowby Hill, a lot of research went into that. We had a local archivist, he worked very hard at it all. We met a girl, a woman then, as a girl she’d been stationed in that area where the crash took place and through personal contact we were able to be sure [emphasis] that where we put the memorial was exactly where the crash took place, so that was very helpful. But the trouble is Anne now, for me is that my memory is shot to pieces and I can’t remember clearly. I can’t , even though a few moments ago I had it clearly in my mind I can’t remember everything that I was told unless I wrote it down.

AR: Thank you Alun, what you’ve been able to tell us has been marvellous.

AEJ: Well you’ve been very kind and I’ve know it’s not been adequate.

AR: It’s been wonderful and it will be a great addition to the archive. Thank you very much.

AR: Thank you Alun for agreeing to talk to me today.

AEJ: My pleasure.

AR: Also present at the interview is Julie Emlyn-Jones, Alun’s wife.

AEJ: That’s right.

AR: So Alun, could you tell me something about your early life?

AEJ: My early life? Well I was brought up in Cardiff, my parents - I was one of two children, my sister was six years older than me and I was the second one and I spent all my early life here really. Then at the age of ten I was sent away to school, I was banished to England for my education. I was very unhappy at school, it was a very difficult time for me, it was just emotional. I was a home boy, I wanted to stay at home I didn’t really want to go but I went to Summer Fields in Oxford to start with and that’s in my book under the title ‘Nightmare’ [laughing] and then I went on to Charterhouse, which was easier. And then, heaven knows what might have happened, I might have gone on to university and so on I suppose, but as a matter of fact I don’t think I was all that scholastically brilliant because I wasn’t working as much as I should have, but the war came to make my decision for me. So I was able then, my parents let me come home waiting for whatever should happen. When it came to, as you know if you volunteered, even if for a short while before you would have been called up you got the privilege of putting down preferences of where you would go, and I must say I wasn’t directed by anything more noble than the fact that I didn’t really want to slog through muddy trenches, so I decided on, you had to put one for each service. So I put my priority as aircrew in Bomber Command, my second one was the submarines and my one for the Army was in tanks, so the idea was that I was going to be carried wherever I was going [laughter] and in due course I was given my first choice and I went to Penarth, I’ve skipped a lot of my youth I’m afraid, went to Penarth to start training there. I’ve skipped a lot, you want to know more about my youth of course.

AR: No, whatever you want to tell us, it’s fine. So your training was in Penarth?

AEJ: We started our initial training, well we started, we met in Penarth before we were sent out to our stations, you know. We went to various places, all over the place. I spent a lot of time training in South Africa, went out on a troop ship, it took six weeks out and six weeks back, incredible, and did my training in a place called East London in South Africa and then came back in due course.

AR: And what did the training entail Alun?

AEJ: Well I suppose we did a lot of flying, Ansons and aircraft like that and then we graduated I think to Whitleys and it was on Whitleys that I was flying with my first crew at the conversion unit. At that point, at the conversion unit we moved to Halifax, the Halifax which we were going to fly during operations. And that’s what we did, so we flew in the Halifax on a regular basis from RAF Rufforth on the flat plain of York and then one day, my crew, well I had my appendix out, that was a very important thing for me. I had an appendix attack. I was able to get home, or it happened somewhere where I could be at home and I had my appendix attack and I had my appendix out in a local nursing home in Cardiff. I wrote to my skipper Stanley Bright ‘I do worry about one thing’ I said, ‘because this has caused me to leave you now and you may not be able to wait for me’. He said ‘don’t worry a bit, the weather’s clamped, we’re doing very little flying, you’re going to be back in a few weeks and that’ll be fine’ And that was the last I heard of him, from him. They were flying from Rufforth on one of their training trips, conversion trips while I had my appendix, they had taken off but they were In, I think, 10/10ths cloud and they were doing simply something like, a simple exercise, I think something like circuits and bumps, you know landing, taking off, landing, taking off, all that sort of thing and I think they got slightly off track in this dense cloud and didn’t realise, because we didn’t have the sophistication with radar that they have now and didn’t realise that the hill, called Garrowby Hill was between them and the ground and they flew into the hill. They killed a passing truck driver and the plane hit the road near Cot Nab Farm, top of Garrowby Hill and disintegrated in the fields and they were all killed. So suddenly I was left, an odd bod with no crew and ah, had to wait to see what would happen. But of course that caused quite a lot of delay in when I started flying and so on as you can see from my logbook, and eventually I was adopted by a crew whose bomb aimer had been taken, borrowed by another crew, and when he was borrowed he was killed. So they ended up as a crew without a bomb aimer and I was a bomb aimer without a crew and they asked me if I would like to join them which of course I was, I was delighted to because that period of just hanging about, just going wandering about the station, not belonging to anybody was a very difficult time, a very, very difficult time. What I couldn’t understand was the attitude of the, I don’t know who he was, one of the senior officers. I couldn’t understand his sort of antagonism to me. He just interviewed me and wanted to know what I was doing and things like that, and then he said ‘get out’. I couldn’t understand that but later, I think I saw that he had been unaware of me not being killed at the time and included me in the list of those who had died that day and I think that he was feeling guilty about that and took it out on me. There was no other reason, I had no personal contact with him that otherwise could have caused that but that made me feel even more isolated really and I just wandered round very lonely and hopeless for quite a while until my new crew adopted me.

AR: And then you flew a number of missions?

AEJ: Well first of all we had a lovely pilot, he was a great guy, Danny and he’d done 13 ops and crashed with a full bomb load. He broke his back and he’d nevertheless come back to flying again and he adopted us and I had great admiration for him, I think we all did. But I of course, as a bomb aimer it was only over the target that I was in charge really and the rest of the time I did odd jobs. I was assistant pilot, I was assistant navigator and all the bits and pieces that went with it, you know helping the wireless operator and anything they could find for an odd job man really. I used to sit next to Danny on take off and as he pulled the heavy aircraft off the ground he would come out in an absolute sweat and I knew he was in pain. After he’d done six or seven ops or whatever it was, one day we were actually out on the dispersal point waiting to take off and he called us together and he said ‘it’s no good I can’t fly, my back is playing up so badly I’ll kill us all’. And I just said to him, because I thought it would be true, ‘don’t worry Danny they’ll understand’. Well they didn’t. The Wing Commander came out in his Hillman and he treated Danny as though Danny was a traitor of some sort. It was dreadful. He said ‘King get into my car’ and then he turned to us and he said ‘I’m sorry your pilot is LMF - lacking in moral fibre’. I thought that was terribly cruel and we asked if we could have an interview with the Wing Commander, which he granted and I was the spokesman and I went in on behalf of the others, with them, and said ‘we want you to know sir that we have great admiration for Flying Officer King and I told him about his broken back, he ought to have known that from the records, and how he’d carried on despite that and how I could see how much pain it gave him when pulling the aircraft back and that in the end he decided that to save us all, he wouldn’t fly. He said ‘your comments are noted gentlemen’ and that was that. Danny was banished from the airfield and we never saw him again.

AR: How did that make you feel, you and your other crew members?

AEJ: Oh very badly about that, very badly. Then my third pilot came into it and took us over and we went on eventually and completed our tour. Well actually they did the full 30 ops and because I had missed one, the one they were on, actually the first one that I’d missed was the Nuremberg trip where we lost more aircraft than any other raid. Because I’d missed that I was officially granted my tour on 29 ops, that was that. That was how that ended and then I got on to Transport Command and so on and I was [emphasis] going to be posted to Japan and that really frightened me. I’d heard such awful stories about prisoners of war in Japan and I thought that was going to be dreadful and I said to then Wing Commander, I don’t know if it was the same one or not, ‘I wonder if I could have a training job of some sort for a while?’. He said ‘you ought to be honoured to be chosen for Japan’. I could have done without the honour. Anyway, the awful thing, but nevertheless, it saved my bacon, what was it, the atom bomb? Yes the atom bomb, because of that the war became over, the war with Japan finished and thankfully for me, I was saved the task of going out there. Then I went on to Transport Command and did various things and I flew quite a lot really but that was the end of my active [unclear]

AR: Where were you in the transport corps Alun?

AEJ: I can’t remember but I’ve got it in my logbook which is there. Yes I’ll have to look it up.

AR: After the war finished, what did you do then?

AEJ: Well, I had been, before the war, before I got called up, working with a little firm called Copy [unclear] Ltd at Treforest Trading Estate, near here, where we made carbon paper and typewriter ribbons. Before the war, as a young man I was pressing green buttons to make a machine go, red buttons to stop it, and things like that and when I came back they said ‘you’d better go in the sales department’, so I spent a lot of time writing sales letters. Which suited me because I like writing so that suited me very well. What was I going to say now, I’ve forgotten.

AR: Well you were talking to me about after the war. Tell me when you did all the work to create a memorial to your crew at Garrowby Hill.

AEJ: Yes, that’s the memorial there. We go up every year. Julie was able to take the service, bless her, as a, what is it for your church, you are a?

JEJ: That’s not part of it.

AEJ: I wanted to say it.

JEJ: I’m an elder.

AEJ: That’s it - I can’t remember things. She’s an elder at the church, so she is able to take the service, which she does wonderfully and we have, very often, and we’re hoping for the same number this time, about 40 people gathered on the hilltop for that occasion. So we do that every year on Armistice Sunday.

AR: And it was you who got the memorial put up?

AEJ: We did, we arranged that, or I did I suppose, well we both did, didn’t we? Yes we both did. We arranged it. We got very friendly with the people who did it, they did a lovely job as you will see. We’ve got the aircraft on the top and it’s a beautiful memorial. They come every time, the people who made it and I think he’s very proud of it and we’re very proud of what he did, it was a great job. That’s what we do every Armistice Sunday. We’ve done, how many? Huge number. A very big number anyway of these, for years and years and years.

AR: And you still keep in touch with - ?

AEJ: It was the seventieth we stopped at, no that was something else wasn’t it?

JEJ: Yes.

AR: And you’ve kept in touch until recently with your old colleagues from the war?

AEJ: I suppose I haven’t really. I’ve lost contact now.

AR: Alan can you tell me about going up to see the memorial and how you feel about Bomber Command being recognised now?

AEJ: Oh very thrilled, very thrilled, yes. Of course we had a lot of fighter boys here and they turned the tables really at that vital moment, but all the boys at St Athans were in fact killed. Every one that we knew, we knew well. My sister was a very attractive girl, and very vivacious, and she had a circle of friends wherever we went and she knew a lot of the pilots. We used to go and stay locally at Porthcawl at the Seabank Hotel and a lot of the pilots from Battle of Britain were there and they all died, sadly. But I think I’m wrong about not having any contact with my crew but my memory, it’s been shot to pieces. [pause] Nobby, Wilf, Geoff Taverner, yes. My bombing leader, Geoff Taverner, he lives in Newport so although we didn’t fly together, he was the bombing leader for my 51 Squadron and I see him quite regularly. He got the DFC actually. And I, incidentally, have just been awarded the medal Chevalier de la Legion D’honneur because quite a lot of my trips were in support of the French and a friend of mine over there, [unclear] Thomas, he said ‘you really ought to apply for the Chevalier Award because I’m sure, knowing your record that you would qualify’. And I did and I was. And Geoff as well, Geoff Taverner. We had a very moving occasion in Cardiff for that. It was rather lovely and the family were able to be there and it was fantastic really.

AR: Congratulations, that’s wonderful.

AEJ: It’s a nice title to have. It’s a wonderful medal, very, very handsome.

AR: That’s lovely to hear. So after the war Alun, life continued and you were working in Cardiff?

AEJ: That’s right and then I got to feel that, it was pure chance really. I wanted to help the people. Because there was a tendency to have a drink problem in my family, on my mother’s side, one of my uncles had a problem and my sister and I both inherited it. And I thought, when I heard about this job, an organisation was being formed in Cardiff, the Council on Alcoholism, if I could get in on that I would be able to help others as well as myself. I applied. My sister, however continued to drink although she was married and she had two children and a loyal husband and she didn’t mean to do these things but she couldn’t stop, you know. She was wonderfully talented, a very gifted and bright girl who drove cars at great speed. She was a tremendous character but she couldn’t quite come to terms with this and I was worried about her and it was because of her, as much as anything, that I thought if I join, if I get in on this job, I’ll learn enough to help her properly and she died the very day I was appointed. But I was appointed, and having put my shoulder to the wheel, as it were, I thought that’s what I’ll continue to do and it became my life’s work. I built up a hostel for people with the problem in Cardiff, Dyfrig House and then moved on and did Emlyn House in Newport. And then we moved on, out into the nearby valleys and did a third one, the Brynnal [?] and then my daughters, two of my four daughters, decided that this was for them so they came in, Rhoda and Lucy and played their very significant role and Lucy became the Director of the Gwent Alcohol Project and Rhoda was in charge of the Community Alcohol and Drugs Team and so we made it a family business [laughter] .

AR: That’s wonderful.

AEJ: I think over the years we were able to help quite a lot of people. The hostel in Cardiff for example, Dyfrig House, we had a Day Centre and a workshop, we had crafts that people could make and all sorts of things as well as having accommodation and support, so there was a lot happening.

AR: Wonderful. Is there anything else Alun you can remember about your - going back to the RAF, your time in Bomber Command, anything else you would like to tell us about what it was like to fly on the Halifaxes?

AEJ: Well I liked the Halifax. The Halifax of course was overshadowed a bit by the Lancaster, in the same way really as the Spitfire outshone the Hurricane. The Hurricane did a very fine job nevertheless and the same applied to the Halifax. It was eclipsed by the glamour of the Lancaster. But I liked it, on a practical basis it had much more room inside so you could move around more easily. Also, which I think is a very important point, it was easier to bail out of [laughter] . It was a good sturdy workhorse and I got very fond of it yes. It just didn’t get the glamour and people always think of Lancasters, they don’t think of Halifaxes. Of course before that, there was the Stirling, after the two-engined ones. I didn’t fly in those, I think I got one trip once but not an operational trip and of course before that we were on Whitleys. We were flying Whitleys. Yes I liked the Halifax very much indeed. I enjoyed flying actually. I mean compared with my friends who are in civilian airlines who drew thousands and thousands and thousands of hours, the whole war I think my total was seven hundred and fifty but seven hundred and fifty hours we packed a lot of stuff into it. I find it such a privilege really to work with crews like that. We became great friends, that’s the thing, it wasn’t just that we were working together, we became great friends. You know we went out together as well and met socially when we could. Oh it was tremendous comradeship. I deem myself very fortunate indeed to have had that opportunity and of course to have survived because the expectation of life was only six weeks, and so to have survived was extraordinary good fortune. We were losing boys all the time. You know, ‘so and so bought it’ that was the expression, ‘so and so bought it’ so you know one of the people we knew well hadn’t come back, they had crashed or been shot down. I mean on one daylight (sortie) I remember seeing lots of aircraft going down. Later, this particular man, lives in Cardiff so I see him quite often because I’ve got a group called 51 Squadron and Friends. The group meets quite regularly and I saw this aircraft just below me, being shot down and it turned out to be his so I was able to tell him I’d actually seen him shot down. He was then captured by the Germans but they treated him with respect. Another of my friends who was shot down in the First War was put into Pfaffenwald which was dreadful and he had a dreadful time there but then the Luftwaffe itself said ‘you shouldn’t have this man there, he should be in a proper prison, so he was transferred, that surely saved his life although he died young in the end, but that was a separate matter. But er, yes there was great comradeship. I’ve rambled on enough I think.

AR: Not at all, it’s been fascinating.

AEJ: Thank you so much.

AR: No thank you, thank you Alun very much for giving us the time.

AEJ: It’s was my pleasure. I just wonder how many things I’ve missed out.

AR: Alun we’re going to carry on now. Can you tell me a little bit about your nickname?

AEJ: Actually of course so many of my compatriots from Wales were called Taffy and I suppose I would have been but in fact Grem fitted in very well and I got called Grem all the way through my Air Force career. That’s because it’s short for Gremlin and Gremlin was the little creature who used to disturb our instruments in the aircraft, imaginary one I need hardly say [laughter] . It was short for that and it also rhymes with my name Emlyn, Alun Emlyn. So for those two reasons I got called Grem and enjoyed that nickname and I’m still called Grem by some people. Geoff Taverner my colleague and one time bombing leader from Newport, he still calls me Grem for example, so it’s very nice to have that.

AR: And animals played an important part for you.

AEJ: Yes, well when we were stationed at one place I picked up a goat, a little goat. He was a dear little thing and he used to live in my billet and used to greet me with licking my face at night and things like that but then he got bigger and bigger and bigger and I had to think of something to do with him so we asked a local farmer if he, no we didn’t, we found a spot at a water tower in the village and he would have shelter and he was on a long lead and we had him there for quite a while and then one time he got away from his lead and went all round the village eating the tops off people’s plants. That became rather unpopular so I gave him to the local farmer on the strict [emphasis] understanding he would be used for breeding and not be killed. So I hope that’s what happened, I hope he had a happy life. Then we had our dog, Jimmy, I picked Jimmy up somehow and Jimmy sort of lived constantly with us and was a great guy. I can’t remember what happened to Jimmy in the end.

AR: Did Jimmy wait for you when you came back from - ?

AEJ: Yes Jimmy used to be there. Wherever we’d been and wherever he’d been in the meantime , he was always waiting on the tarmac when we got back and he lived in my billet with me. So we had a bit of a menagerie really. I can’t remember what happened to Jimmy, pity we can’t ask [laughter]. So there we are and of course when we searched for the spot to put the memorial for the first crew at Garrowby Hill, a lot of research went into that. We had a local archivist, he worked very hard at it all. We met a girl, a woman then, as a girl she’d been stationed in that area where the crash took place and through personal contact we were able to be sure [emphasis] that where we put the memorial was exactly where the crash took place, so that was very helpful. But the trouble is Anne now, for me is that my memory is shot to pieces and I can’t remember clearly. I can’t , even though a few moments ago I had it clearly in my mind I can’t remember everything that I was told unless I wrote it down.

AR: Thank you Alun, what you’ve been able to tell us has been marvellous.

AEJ: Well you’ve been very kind and I’ve know it’s not been adequate.

AR: It’s been wonderful and it will be a great addition to the archive. Thank you very much.

Collection

Citation

Anne Roberts, “Interview with Alun Emlyn-Jones,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed November 8, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/8832.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.