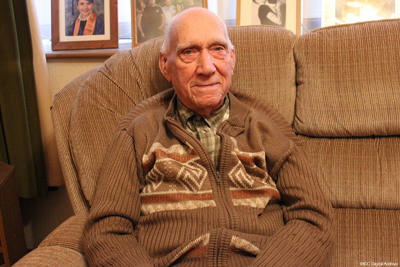

Interview with Louis Makens

Title

Interview with Louis Makens

Description

Louis Makens worked as a farm worker before the war but volunteered for aircrew. He discusses his training on Wellingtons and operations flying Stirlings with 196 Squadron including a crash landing, and glider towing. His Halifax was shot down 18/19 March 1944 on the way to Frankfurt. It was his seventh operation, but his first as a mid under gunner with 76 Squadron from RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor. He became a prisoner of war and discusses that as an extra gunner with a new crew, he only got to know his pilot David Joseph during captivity. He describes his capture and treatment and the conditions at Stalag Luft 6, the contents of Red Cross parcels, and the prisoners' attitude to the guards. He describes the conditions on the long march through Germany away from the advancing Russians. Eventually he found the advancing Allied army. After the war, he was remustered as a driver and was demobbed in 1946. He found employment with Stramit manufacturing strawboard building material.

Creator

Date

2017-01-17

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:42:22 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

AMakensL170117, PMakensL1701

Transcription

DK: Right. So this is David Kavanagh for the International Bomber Command Centre interviewing Louis Maken.

LM: No. No. No.

Other: Louis.

DK: Louis. Sorry. Sorry. Louis Makens.

LM: My grandson. He don’t like it.

DK: Misinformed. I was misinformed [laughs] 17th of January 2017. If I put that there.

LM: Yeah.

DK: If I keep looking down I’m not being rude I’m just making sure it’s still working. I’ve only been caught out by the technology once. It was a bit embarrassing.

LM: It wouldn’t take a lot to catch me out.

Other: No. It wouldn’t.

DK: Right. Ok. What I’m going to ask you first of all was going back now what were you doing immediately before the war?

LM: I worked on a farm.

DK: Ok.

LM: Market gardening and ordinary agriculture on a farm.

DK: Ok. So and then war started. What made you then want to join the RAF?

LM: We had, we were called up weren’t we? We had to register and I went for an interview and they gave me the choice of what you’d like to do and not being very smart I volunteered for air crew.

DK: Right.

LM: And went back to work and I suppose it must have been about a few months. Something like. I was about nineteen I got my call up papers saying to report to Uxbridge.

DK: Right.

LM: That was where they had done all the interviewing.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And they asked you silly, well not silly little questions I suppose but half multiplied by half. That was one of the questions on, at the interview. And another one was if the Suez Canal got blocked how would the transport, how would they get cargo around to England?

DK: Oh right.

LM: And which was a long way around.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: The Cape of Good Hope, wasn’t it? And from then on I just had my papers come in. Called up. Report to Uxbridge and then from Uxbridge I went to a place called Padgate. We were kitted out at Padgate and I actually volunteered wireless operator air gunner.

DK: Right.

LM: And I’d done Blackpool in 1942 and there were some old hangars there where we used to do Morse Code [coughs] Morse Code in and I had a spell there and they asked for straight air gunners which was a lot quicker course.

DK: Right.

LM: Why? I don’t know why I volunteered for that. I don’t know to this day. Anyway, I volunteered and I was taken off the course there and from then on I had a life of leisure.

DK: Right.

LM: I went to a place called Sutton Bridge. That was a fighter OT Unit.

DK: Yeah.

LM: General duties. From Sutton Bridge the whole squadron moved up to Dundee and under the Sidlaw Hills. And there was a Russian aircraft landed at the airfield at Dundee.

DK: Oh right.

LM: And the camouflage was really marvellous.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And that was where I was on general duties up there as well. What we were doing going around with little bits and pieces. Anything. Anything there was to do which you’d gather what general duties mean.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Everything. And then I was called to, I got my call up from —

DK: Just stepping back a bit you never found out what the Russian aircraft was doing there then.

LM: Yes. Molotov.

DK: Oh right. Ok.

LM: Molotov came over.

DK: Oh.

LM: I’m sorry about that I should have —

DK: Did you actually see him?

LM: Yeah. No I never. No. No.

DK: No. Oh right.

LM: Only saw the plane at a distance.

DK: Oh right.

LM: Oh yeah.

DK: Wow.

LM: And it was quite funny really because I wouldn’t have believed it. There was a Scottish lad worked with me and he said to me, ‘Louis,’ he said, ‘How would you like to my parents and just meet my parents and just have a cup of tea with them.’ They lived in Dundee.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I had to get him to interpret what they said. I [pause] Dundee was really broad and I felt a really Charlie because you had to say, ‘Sorry. What did you say?’ and I had, I had to say things like that. But from there on I got called back to a place called Sealand.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: And that’s where I met up with two lads who had already been the same thing as me further afield but they’d been on a wireless so they had decided to remuster as well. Quicker course. We’ll get in to action. Silly weren’t we?’ Anyway, Stan Gardiner was one of them and Harold Lambourn and how, I think Stan Gardener was a welterweight boxer. I didn’t realise that at the time.

DK: Oh right. Yeah.

LM: But I often wonder. We parted because they remustered as pilots.

DK: Right.

LM: And I remustered to straight air gunner. Well, while we were at Sealand we used to go with a Polish squadron and fly with a Polish squadron in Lysanders. Dive bombing for the ack ack training. And we used to fly up the Dee and almost looked up at the houses because you approached and then they’d quick climb and then dive on their guns.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But then I was posted to, from there I left them and I was posted to [home] house in London. That’s where we done the Lord’s Cricket Ground. Was it Lords or the Oval? One of those. And that’s where we’d done gas training and things like that and from there I was posted on to Bridlington and that’s where I done my gunnery, ITW for the second time.

DK: Right.

LM: And from there I was posted on to Stormy Downs.

DK: What did, what did the training involve then at ITW?

LM: At the ITW?

DK: Yeah.

LM: It was back to square one. You know what I mean by square one? Square bashing.

DK: Oh right.

LM: But we did go in to, Bridlington had on the front there was a shooting range. A twelve bore shooting range. Clay pigeons.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I won the competition and won twelve shillings and sixpence. And there was —

DK: You obviously went into the right duties then as an air gunner.

LM: I came away the best shot of the lot. I suppose I must have been. But no. But cutting it short there at Bridlington and then Stormy Down. From Stormy Down we went to Stradishall.

DK: Yeah.

LM: First we were on Wellingtons and then Stradishall was conversion on to Stirlings.

DK: Right.

LM: Now, I think —

DK: Just stepping back can you remember what it was you were flying at Stradishall? Just —

LM: Stirlings at Stradishall. I’m trying to think where I’d done my OTU. I’m not so sure where the Wellington, when I’d done the OTU on. I went to so many places. I’m not sure if I could swear blind.

DK: No.

LM: Where the Wellingtons were stationed. Where we, they had so many of them.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But I finished up at Stradishall and that’s where we were crewed up and already crewed up and I happened to be the seventh member of the crew.

DK: Right.

LM: Which I was a top gunner. A mid-upper.

DK: How did the crewing up work?

LM: Just, I was just introduced to them.

DK: Right.

LM: They were already crewed up.

DK: Right.

LM: But as they —

DK: They needed a gunner.

LM: As a yeah. They had to have a top gunner.

DK: Yeah.

LM: For the start of the four engines. Then finished Stradishall. And that’s where I’d done the odd circuits and bumps and that sort of thing. And one particular night I was laying in bed and I heard this machine gun fire and it was a Focke Wulf had come back that night. I got up the next morning. A Focke Wulf had come back and shot one of our planes down doing circuits and bumps and the only one hurt or I think I’m sure the news was that he got killed and he was Canadian. And he was a screened pilot. What we called a screened pilot.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Was one who, you know —

DK: Already done a tour.

LM: Already done his tour and I think he was teaching us to land.

DK: And he was killed in a, back in the UK while training others.

LM: Yeah. A fighter come back with the bombers to wherever they were going to or from and must have picked up Stradishall and that was how. So the next night we had to go. I was on the next night on circuits and bumps and of course the warning was if there’s a bandit in the area all the ‘drome lights would go out.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And of course, what happened? All the lights went out didn’t they? And we were still stooging around, stooging around, stooging around, waiting for well we didn’t know what was going to happen. Everybody was on edge and all of a sudden the lights come on. It was a dummy run. So we were a bit relieved about that but then after my OTU there and the, and the conversion at Stradishall I was posted to 196 Squadron Witchford.

DK: Right. Ok.

LM: As the mid, mid-upper gunner.

DK: Still on Stirlings.

LM: Still on Stirlings.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Yeah.

DK: So what were your thoughts about the Stirling then when you first saw it and flew in it?

LM: Well, as we went to Stradishall they stood behind almost on the edge of the road where we went.

DK: Right.

LM: And they were massive and if you can imagine what a Wellington was like. Quite low down.

DK: Yeah.

LM: You could almost touch the nose. These Stirlings. They’re twenty two foot to the nose in the air. I have to be careful what I say if this is going down on there. But —

DK: We can edit the bits out later.

LM: Well, yeah. You’ll better cut this piece out because I think what happened our pilot who he’d been out in Rhodesia, flying out in Rhodesia and I think when he saw them he got a fright.

DK: Really?

LM: We had [laughs] we had some near misses. Or near tragedies. When you come in to land you’ve got your three lights. Red too low.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Green. Lovely. Amber too high. We would come in on no lights at all.

DK: Right.

LM: Nose down. And I just used to sit there like that. ‘Christ, what’s he doing?’ And I could have landed the plane quite easily because when you sit in that top turret a beautiful view and I used to sit on the beam like that and check, check, check and I could get that to a tee. I’m not boasting about how. I couldn’t fly a plane anyway. But the bomb aimer, the wireless operator he had his parachute like that every time we landed and we came in —

DK: Not giving the pilot confidence is it? Or having confidence in your pilot if he’s doing that.

LM: No. None whatsoever.

DK: No.

LM: We’d been to Skagerrak mine laying and we came in this night and I got caught sharp a bit. Get down a bit. Down a bit. A bit high. Came in. Bang. We hit the ground, smashed the undercarriage up.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Soared up unto the air and of course came down again and the undercarriage had gone because we went down on to one wing and slid, as luck would have it we went off the runway onto the grass. We never did land on the runway or take off on it. There was either run off at the end or whatever. Oh, you have got to watch what you put on there haven’t you? [laughs] He might be alive. I don’t know what happened. Later on I was, we didn’t, we went on, went from Witchford to Leicester East. Irby.

DK: Right. Just going back to Witchford can you remember how many operations you did from there?

LM: Altogether there was six.

DK: Right.

LM: That was the seventh one. Number seven on the night we got shot down.

DK: Right.

LM: And that was the first time on the first raid we’d done with, first I’d done with Halifaxes.

DK: Right. So when did you convert to the Halifax then?

LM: Well, I didn’t convert. I was just, we were made surplus.

DK: Right.

ILM: We went towing gliders and that sort of thing and eventually that was what they called we were transferred to what they called the AEAF. That’s the Allied Expeditionary Air Force so therefore they decided they didn’t want a top turret. Extra drag. Which you would get wouldn’t you?

DK: Yeah.

LM: With the top turret on so we were made redundant in a way.

DK: Right.

LM: And there were six of us were taken off 196 Squadron and we were posted to Marston Moor and from Marston Moor we were then sent up to Holme on Spalding Moor. They had then fitted a gun emplacement, a beam if you’d like to call it that underneath the plane.

DK: And that’s on the Halifaxes.

LM: That was on the Halifaxes.

DK: It was like a belly gun in effect.

LM: A mid-under they called it.

DK: Yeah. Right.

LM: It wasn’t a turret as such it was just a, it was a piece of metal stuck on the bottom as near as near as I can explain it.

DK: Right.

LM: You had a .5 between your legs.

DK: Was that something the squadron itself had done or was it an official —

LM: It was what they were trying to get.

DK: Yeah.

LM: We were getting so many attacks from below.

DK: Right.

LM: Because as you know you can’t see below your own height can you?

DK: Yeah.

LM: It’s very difficult to see. You can see upwards but you can’t see below your own horizon.

DK: And were you aware at the time that a lot of the attacks by the Germans were from underneath?

LM: It was known.

DK: It was known.

LM: It was well known.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Oh yes. Yeah. That was well known. That was the idea of fetching this gun underneath.

DK: Right.

LM: And the Germans knew very well that we were [pause] well no protection underneath at all coming up from —

DK: So, you’re now with 76 Squadron at this point.

LM: That was 76 Squadron.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Yeah.

DK: So, you’re now in the, in the belly.

LM: That’s it.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Well, I had never met my crew that I flew on that night with.

DK: Right.

LM: We went to briefing. We went, we’d done a little bit of training on it. There weren’t all that much more training to do. It was only sort of getting used to a .5 and that sort of thing and a fair old go on that.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And the first time I actually met my crew was when I was a prisoner of war.

DK: Oh right.

LM: Well, after I’d been shot down I should say.

DK: Right. So you only did the one operation [unclear]

LM: That was the very first one.

DK: And you were shot down.

LM: We were shot down the very first night. There was six of us went and I think there were three of us allocated to go that night.

DK: Right.

LM: March the 18th 1944. I should have been at a wedding.

DK: Can you recall where the operation was to?

LM: Yes. Oh yeah. Frankfurt.

DK: Frankfurt. Ok.

LM: Yeah. Frankfurt. And we were about twenty, twenty minutes from the target.

DK: Right.

LM: And everything was quiet. Not a very good thing in a way and we hadn’t crossed any borders as such for anti-aircraft or anything like that and every now and again the pilot would just call up and say, ‘Are you alright?’ And so forth, ‘Gunner.’ So forth. And the next thing I knew there was a blaze of bullets, well incendiaries, you couldn’t see the bullets. Incendiaries. And I sat in the turret like that you see facing the rear and the bullets came through, went between my legs. Almost. I was stood. They went between my legs. Well, there was the pilot looking out the front. There was the navigator [pause] could have been I suppose. The bomb aimer should have been in the, in the astrodome looking out. Top gunner in the top turret. The only two of us who saw the bullets were myself and the rear gunner.

DK: And this was from a German aircraft presumably.

HLM: That was [laughs] that’s hard to say.

DK: Oh right.

LM: I don’t know. We never saw the plane. It was head on.

DK: Right [unclear]

LM: So was it one of ours?

DK: Ah.

LM: Well, I’ll never know.

DK: No.

LM: I don’t think so.

DK: No.

LM: But they were fairly heavy. It weren’t small machine gun fire so it could well have been a night fighter. And when you think that no one up front saw the tracers at all.

DK: Were they an experienced crew do you know? Or —

LM: Were they —?

DK: Were they an experienced crew that you —

LM: They’d done, they’d done seven nights. They’d already done seven operations.

DK: Right. Ok [unclear]

LM: Yeah. And four that night.

DK: Right.

LM: Yeah. Yeah. They weren’t over experienced. Like I was I suppose. But, but they hadn’t, they, I sometimes think how ever I got away with being missed in that dustbin when you think of the midair of that aircraft wing as mid —

DK: Yeah.

LM: Fuselage.

DK: It’s, you’re in there then.

LM: That’s right. That little bit underneath.

DK: Yeah. Do you know what other damage was done to the aircraft then? Or —

LM: Well, we caught on fire.

DK: Right.

LM: Yeah. They hit the inboard. The inboard starboard engine and I thought well that’s all right. With the old extinguishers put the flames out. Anyway, we went on a little while and there was quite a, it was getting quite light then because we were on fire and the pilot, David Josephs was my pilot. Never knew him at the time.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But I found out later on and he said, ‘Prepare to bale out.’ Which is the first thing, isn’t it? So I opened my hatch up and just stood there. Kept on the intercom. Kept on oxygen and the top gunner he’d already got out of his turret and he came down and opened the back hatch.

DK: Right.

LM: And he must have thought because it was quite light because of the flames and so forth and he thought, I think he thought I’d been hit because I was still in the turret and standing up. He came back and he went to get a hold of me like that and I went, ‘Ok. I’m alright. I’m alright. I’m ok.’ Well, the pilot hadn’t told us to bale out then. But he did eventually say, ‘Right. Well, better get out. Bale out.’ So that was myself and the top gunner. We went to the back hatch and when you go out you have to roll out otherwise you’re likely to hit the tailplane or the fin.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Which is easily done. So it was quite comical in a way. It must have been a comedy act. We stood near the hatch or laid near the hatch arguing who was going out first. I’d, I’d seen it happen. People who baled out and they’d extinguished the flames, the [unclear] switch or something like that.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And put the flames out and they’d flown back.

DK: Right.

LM: I thought I’m not going to be, I’m not going to be here on my own so we, Spider went out first and I toddled out behind him. But I went out with my arms folded like that because when I put my parachute on you don’t wear it all, you sort of have it beside you.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: So I quick put on my hooks.

DK: So you [unclear] then

LM: Clipped them on the hooks.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: And I think what happened you’re supposed to leave, lose speed count up to seven because you’re travelling at a hundred and something, a hundred and eighty mile an hour. The first thing I knew, bang. The parachute had, whether the slipstream caught my hands and my parachute, must have pulled the parachute, the rip cord.

DK: Yeah.

LM: The next thing I knew that was bang. Oh, the pain, the jerk on your neck. People don’t realise it’s a —

DK: As the parachute opened.

LM: Oh yeah.

DK: Yeah.

LM: It almost feels like you break, you know.

DK: So is it is it a chest ‘chute you’ve got then?

LM: Yeah. Chest.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Chest it was. No seated ones then. We always carried them and just stuck them in the little hole at the side of the, of your turret.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And anyway, I don’t know how long it was coming down but when I looked down I thought, oh shite. Water. I thought I can’t be over water. That’s one thing I always dreaded. Coming down in the, in the sea. And what it was the plane was on fire and that had gone down and there was snow on the ground and little hillocks that looked like waves.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: And [unclear] It just looked like a patchwork of little waves. Anyway, the lower I got they disappeared. Anyway, I hit, the next thing I knew I was laying on my back groaning. I can remember now as if it was yesterday I laid there and thought oh, oh. I sort of shook myself up and of course up I got and I tried to pull the parachute in and got caught on a tree.

DK: Right.

LM: Right on the edge of a wood. As I went to pull the parachute in I thought, oh Christ there’s someone there. One of my old crew. So I sort of called out. No answer. It was just somebody falling in.

DK: Yeah.

LM: It wasn’t a crew at all. It was a piece of grass that was just doing that with the back light, the back sight of the flaming plane where it had gone down on the horizon.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Was casting this little piece of grass going along. I could imagine someone pulling a parachute in.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Anyway, I couldn’t get the parachute off the tree. I tried to get it down and I had to leave. What I’d done I just curled up under a hedge and I don’t know where the hell [pause] escape kit. Lost it. I had it, you had it park it on the side of your leg and it must have come out as I was upside down or —

DK: What would have been in the escape kit you’d got [unclear] ?

LM: Oh, you’d got a map.

DK: Right.

LM: Chocolate. One or two. Quite little bits of ration material.

DK: Right.

LM: A compass, etcetera but I lost them and so I curled up under a hedge and I had to sleep until it was daybreak. And I got up the next morning and when I woke up and I thought now sun is coming up in the east. If I go towards the sun I might make my way to France. But I wasn’t anywhere near France, was I? [laughs] Not really. I wouldn’t have met, I don’t think I would have, I don’t know. But anyway, I knew I wanted to go east because of the sun coming up and Germany here, France going in that direction sort of business and I thought if I make my way that way I might be able to come up against somebody but I went and I travelled for a day and never saw anybody. The next day I was walking what do you do? I covered my, took my boots and covered them up. I was lucky in a way digressing a little bit normally you know the old flying boot we used to have?

DK: Yeah.

LM: The old fleecy lined things.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Huge things. Well, I hadn’t. My equipment hadn’t arrived at 76 Squadron so I borrowed the squadron leader’s equipment. His flying boots. And we had, I had an electrically heated suit.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Because it was cold. We are talking about twenty two frost and I had an electrically heated suit. That’s your socks and just a jacket and I had his size elevens flying boots. Normally your flying boots fly off which they will do quite easily. That just shows the force of the parachute opening doesn’t it?

DK: Yeah.

LM: And how I kept them on I can only imagine I had electrically heated socks inside them. That’s how I think, the only way I can think I kept those shoes or flying boots three times the size of mine.

DK: So they were wedged in there with the sock.

LM: They must have been fairly —

DK: Yeah.

LM: No end of people. That’s the, my pilot lost his.

DK: Yeah.

LM: He was walking about with a, when I saw him last, the first time I met him he had got pieces of rag wrapped around his feet and that was one of the problems. Getting frostbite.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I think I got a little bit of frostbite on that ear and it’s still there. But lucky I didn’t get any more and no one else did. Anyway, I eventually I got, I did walk into two, I’d compare them with our Home Guard.

DK: Right.

LM: Two old boys walking over a bridge and where the village was, God knows, I have no idea and these two old lads walked towards me and all of a sudden they walked towards, crossed the road towards me like that and he pulled out a big revolver and I, that’s it. So I put my hands up. ‘Flieger. Flieger.’ And they took me back to their headquarters all dolled out with Hitlerites and all that sort of thing on the wall and they weren’t very, they didn’t seem too bad. They were the oldest of people and they took me to their little headquarters and then they had to get the Army to come and pick me up and they took me to another, somewhere else. Got above, it was only a walk from somewhere else to there. Well then, they sent in ex-RAF. The Luftwaffe.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Two of them came and picked me up and I was a little bit lucky in a way because we were walking along. They didn’t bother too much about whether you’d got hit or not. The Germans didn’t care. If somebody hit you with a hammer even. We was walking along and it was a Hitler Youth I think. Something in that region. He came up, he said, a lot of them spoke good English. He said, ‘Did you raid Cologne? Were you on a raid on Cologne?’ I said, ‘No. No. No. No.’ I said, ‘This was my first raid. First time.’ Well, it was a lie because I’d already got the 1939 43 Star on my tunic.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And he didn’t think nothing. He couldn’t have been, he couldn’t have fathomed that one out because well he probably didn’t know what they, what it was anyway.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And he just went away because Cologne was awful one wasn’t it? That was an awful thing.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And eventually they took me to their barracks and they were good. They gave me, the Germans, they gave me a lovely piece of black bread and jam. I’d had one taste of it and I threw it across the bloody cell. I thought, oh Christ and I couldn’t eat it. I just could not eat it. Which I learned different later on. Well, I went and laid on this old bunk of a bed sort of thing and the next thing I knew there was a boot in my back and they, then they brought the pilot. They’d got the pilot.

DK: Right.

LM: And one, I think that was the rear gunner. They’d picked them up as well. And that’s the first time I had met my pilot.

DK: Bizarre.

LM: And we were on our own until we got on with the crew itself.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But for some reason David Josephs, name spelled Joseph, J O S E P and do you remember Keith Josephs?

DK: The politician?

LM: Yes.

DK: Oh yes. Yes.

LM: He was the dead spit.

DK: Oh Right. Oh.

LM: Exact. Exact. Well he palled, why I don’t know.

DK: Yeah.

LM: He palled up with me.

DK: Right.

LM: Not his crew.

DK: Did you think he was related then or —

LM: Well, I would have swore blind he was. He never said. We never spoke about private life. We never told each other what we’d done, or what we did or what we hadn’t done or anything like that. It was just you met them and that was it.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Like when we left we never left any, I often wish I had have done. Kept in touch perhaps with two of the lads I escaped with. I would have loved to have known what happened to them.

DK: No.

LM: But you don’t. You’re so keen to just carry on. Carry on. Carry on regardless of what goes on around you really. It’s —

DK: So were you then sent to a proper prisoner of war camp at that point?

LM: I was taken back. Now this is the bit that really peeved me at one time because I often think of it. They took me back to Frankfurt.

DK: Right.

LM: And I saw Frankfurt’s Railway Station what they were doing to Germany that we were doing or we were getting over in London and I thought the very same thing. There was people on the station with a, one particular person there was a woman with a little child and they’d got a basket, a linen basket like that between them.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And I suppose they were trying to get out. Mind you that was two days after they’d been bombed quite a bit then day and night you see. We were full incendiary. That was all we carried that night was incendiaries.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But that, then I’d done solitary confinement. They put you in solitary there and there was a raid on that night and that [pause] we had all sort of a, there was solitary confinement and there was a blind you could almost it was like a slab of blind and the light, you could even see the lights flashing through this sort of one of these old plated blinds sort of things.

DK: But flashes of the explosions.

LM: Yeah. Of the, of the raid.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Yeah. And I was there three days and they asked you all sorts of questions and a corporal he must, think he was a corporal he looked like it to me. Got a couple of stripes of some sort and he came down and he interviewed so forth to this. He’d got a big list where I’d come from. You only say what you know. Or you’re supposed to say name, rank and [pause] name, rank and whatever.

DK: I was going to ask that. If I could just take you back a bit did you have training as to what to do if you were caught as a —

LM: None whatsoever. We were —

DK: Ok [laughs]

LM: We were just told the general thing. Name, rank and number.

LM: It was a general thing. Name, rank and that’s all.

DK: So you had no other training if you ever were captured.

LM: No. No. that’s all we, never even had trained parachute jumping. Never had. Never had a [pause] The art is the falling over and rolling over you see.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Well, I hit the ground straight legged.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And I think that’s why I knocked myself out. I think that’s the reason. I must have hit the ground straight legged.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Instead of doubling up and falling over.

DK: Yeah. And rolling. Yeah.

LM: Which is the correct way.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I knew the way but you can’t tell how far off the ground you are you see.

DK: At night. Yeah.

LM: And the last fifteen feet or the last little bit was like jumping off the wreck and like jumping off a fifteen foot wall when you hit the ground quite hard.

DK: Yeah.

LM: So that was part and parcel. They’d never done, I don’t know if it was the pilot’s fault or not. I don’t know ‘til this day if he should have made his crew take part in —

DK: Training. Yeah.

LM: Escaping or whatever or what to say what not to say. No one else did. We never had any training of that at all.

DK: And, and dinghy practice. Did you ever have any of that?

LM: No. we were, I did learn to swim.

DK: Right.

LM: At Blackpool and if we could swim a width.

DK: Right.

LM: That’s all you had to do.

DK: So you had no training on what to do if you crashed on water, baling out or — [unclear]

LM: No, we had none.

DK: No.

LM: I think some did.

DK: Yeah.

LM: We had no training whatsoever.

DK: Wow.

LM: Never had. They just, all they told us was when you go out to roll over the hatch.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Rather than the other way.

DK: Avoiding the —

LM: I had seen a lad. He had knocked his teeth out. He’d hit the tailplane. But apart from that we didn’t. It was —

DK: Yeah.

LM: The discipline I suppose we were treated very leniently.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Because when I I thought I was going to get out of a church parade so when I joined up they say religion. I said none. I thought I’ll get out of church parade doing this and they put atheist on my dog tags.

DK: Oh right.

LM: So they were on until the day I lost them.

DK: Oh right. Can I just take you back then to Frankfurt? You were interrogated there after three days.

LM: Yes.

DK: Solitary confinement, so you’ve only given name, rank and serial number and that. What happened after? Next after that?

LM: They don’t [pause] they will keep you there and keep asking you questions and they showed me a list. I thought good God. They could have shown, they could have told me much more than I knew. I couldn’t. I couldn’t. If I’d have wanted I couldn’t have told them anything.

DK: So their intelligence then on the aircraft, the squadron —

LM: They knew every airfield. They knew every airfield and what there was. They got this map of every, almost every airfield in this country.

DK: Wow. Did they know who was based there on these airfields?

LM: They knew the squadrons as well. They’d got the squadrons down. My old squadron 196.

DK: Yeah.

LM: That was down there. I may have shown that because I thought 196 I just and the realised then that —

DK: Yeah.

LM: You don’t think that they’re using you know on the spur of the moment. I thought 196 and Witchford.

DK: So they had all that intelligence. Did they have names at all as to who the commanding officers were?

LM: No idea.

DK: No. No.

LM: No. I don’t. What on the German side you mean?

DK: On the other side. Yeah.

LM: No. I wouldn’t. No. No. There was the treatment we got in the prison camp we can’t grumble.

DK: Right.

LM: I mean we went over there.

DK: Can you remember which prison camp it was?

LM: Yeah. After leaving, after leaving Frankfurt.

DK: Yeah.

LM: On the old cattle trucks and we were going along and I thought oh whatever is that smell? Christ. And there was a lot of us in this cattle truck. I didn’t realise at the time it was an American and he had been, he must have been loose a little bit for a while before he got caught because he’d got frost bite and his foot had got gangrene and I’d never smelled anything like it. He sat with his shoe off and he was like that and I realised then what he’d got. And his foot was absolutely. I don’t know what it was like inside the sock but he’d obviously got frost bite and it had turned to gangrene.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And we called at a place called Sagan. That’s Stalag Luft 3.

DK: So it’s Stalag Luft 3.

LM: That’s the officers.

DK: Yeah.

LM: That’s the officer’s camp.

DK: Right.

LM: Stopped at the officers off or whatever there was to get off there and from there on we travelled through Poland by train and I can’t tell to this day how long so I weren’t one of those who made notes of where we were, what we’d done, it was just one of those things. You accepted what had happened and eventually arrived at a place called [pause] up in Lithuania [pause] Sally, what was the name of it?

Other: I weren’t there grandad.

LM: Anyrate, it was not, not all that far away from, now when you get to my age that happens you know. You lose your train of thought a little bit don’t you?

DK: I do now [laughs]

Other: Yes. So do I [laughs]

LM: But no, I —

DK: So it was a camp in Lithuania.

LM: Stalag Luft, no, Stalag Luft 6.

DK: Stalag Luft 6. Right.

LM: Up in Lithuania.

DK: Right.

LM: That’s right.

DK: Ok. Ok.

LM: Anyway, with the name Twy, I think it was [Twycross] or something like that. We were the furthest north of any camp.

DK: I was going to say that’s someway east isn’t it you were?

LM: Yeah. We were right up near the Russians.

DK: Russians. Yeah.

LM: Because it was a bit [pause] Dixey Dean. A great footballer wasn’t he?

DK: Yeah.

LM: He was our camp leader.

DK: Oh right.

LM: Yeah. Dixie Dean.

DK: Did you get to know him well?

LM: No. No.

DK: No.

LM: Oh no. Didn’t. Well, I knew him.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But he didn’t converse with very [pause] He could speak fluent German.

DK: Right.

LM: Been a prisoner of war for a long while and he used to go to Sagan the officer’s camp and converse with the Germans there on the conditions of camp and all that.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Because he knew the Geneva Convention backwards.

DK: Oh right.

LM: And when we could, 19th June 1944 when, the Second Front —

DK: Yeah.

LM: Now, they knew that in the camp but no one said.

DK: So, it was a decoy then.

LM: They wouldn’t let us know.

DK: No. Right.

LM: They knew that Dean and his escape, whatever they were radio, they’d got a radio because they used to come around and give us the news each night. Someone would come around and just and sometimes a German would do that.

DK: Yeah.

LM: The old goon would.

DK: So how big was the camp there? How many prisoners were there roughly.

LM: I don’t know but I’d hazard a guess. In our camp compound alone there would be one, two, three, four, five, six, sixteen, six, eight. Oh, three or four hundred if not more.

DK: Right.

LM: Yes. They were all officers. All NCOs.

DK: NCOs. Yeah.

LM: And then —

DK: And what were you in? Were you in sort of cabins or Nissen huts or —

LM: One long, one long hut.

DK: One long hut.

LM: There were bunks.

DK: Right.

LM: And if the weather was nice and we were going on parade and roll call then some of the lads would play up and they would nip up or make a count wrong. We reckoned they could only, they could only count in fives the Germans. So we said they could only count in their fives and the lads would play up a bit. But if it was raining.

DK: Yeah.

LM: We used to put a head out the end of the pit and they would come along and count you and we behaved ourselves then.

DK: Right.

LM: But there was a case where we came, we could, later on it must have been getting towards August we could hear the Russians from where we were.

DK: Right.

LM: The tales we heard about what happened to the Russian guards and the German guards when they got taken by the opposite side.

DK: Yeah.

LM: They didn’t take prisoners.

DK: No.

LM: They didn’t take either side. They didn’t touch the prisoners but the guards they shot them. So there was no love lost between them.

DK: No. So —

LM: Well eventually, yeah —

DK: As I say could you briefly describe what the camp looked like? Presumably you’d got barbed wire as a —

LM: Yeah.

DK: Watch towers and —

LM: Yeah. You had the old, I’ve got a couple of paintings upstairs that a fella had done in the prison camp.

DK: Right. Right. So it’s a compound thing.

LM: It was a big, what it amounted to was, was a big area.

DK: Right.

LM: And your huts one, two, three, four. Long huts. About must have been more than twenty yards I suppose all tiered both sides. You had an odd table in the middle and around the outside of that was your walking area.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Always had that. Then you had a warning wire. They called it a warning wire. That was just a little board that ran along. You mustn’t put your foot over that otherwise they would shoot you.

DK: Yeah.

LM: If you put your foot over the warning wire. Then you had your barbed wire.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And then the goons were up in their —

LM: In towers.

LM: Towers.

DK: And you were just watched the whole time.

LM: Oh yes. Yeah. Yeah.

DK: So, what, what did you do to pass the time because days must have —

LM: Walk around the, we weren’t allowed to go out. Now, early on they were allowed to go out as working parties but there were so many RAF tried to escape.

DK: Right.

LM: Escape. And they stopped it. We weren’t allowed outside the camp. Once you were in there you didn’t come out until they wanted to move you which they did us. From the Russians you see.

DK: Right.

LM: And no, we weren’t allowed outside the camp.

DK: And —

LM: It was —

DK: And with the restraints there would have been were you treated well then? Or treated [unclear]

LM: In the camp there was no hard [pause] no. But I don’t think I would say I was treated badly. We went over there to kill them but to me we were treated fairly. Geneva Convention. They abided by that.

DK: And what was the food you got then?

LM: Well, that, now that’s sauerkraut.

DK: Right.

LM: And there was an American parcel and an English parcel. Now, the English parcels, well obviously England was struggling to even feed their own people, weren’t they? So they weren’t the serviceability of the package wasn’t very good because we would get in the British parcel or English parcel we would get condensed milk.

DK: Right.

LM: Well, that weren’t, that wouldn’t keep. But the American parcels were in a nice cardboard box and we’d get oh quite a little bit of chocolate etcetera etcetera and you know different things in there.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And used to tide us over. You’d only get a parcel between perhaps four or five or six or seven of you.

DK: And are these parcels that have gone through the Red Cross then?

LM: Yeah.

DK: So they were done, made up in Britain or America by the International Red Cross.

LM: They were already sent. Yeah.

DK: Somehow —

LM: They were the Red Cross. Yeah.

DK: Right.

LM: But they used to puncture them before they came. They couldn’t empty them but they could puncture the tins before they came in.

DK: Right.

LM: And this went on until when we, we knew the Russians weren’t far away. We could hear gunfire in the distance and we were told this and that, this and that. And then eventually they said we would have, they were going to move us out of the camp to another camp. So we deserved what we got in a way because there used to be what they called in the American parcel it was called klim. It was a lovely powdered milk. It was milk spelled backwards.

DK: Oh right. Yes.

LM: See. That was called klim. Milk spelled backwards.

DK: Yeah.

LM: We had, when you said did they treat us alright we weren’t badly treated as such at all but the food weren’t, it was a bit sparce. I mean we got a loaf of bread and that was black bread between seven.

DK: Right.

LM: And no argument as one would cut it up in seven pieces and you just had a slither of a loaf. No argument at all about how big yours was and how small it was or whatever.

DK: I suppose you had to get on with your fellow prisoners then.

LM: Oh yes. Yes. Because you could soon lose your old temper. I’ve seen that happen but not not very often. Not very often because when well I suppose in a way we were very, everybody was an individual in their way because we weren’t like the Army as such. We didn’t mix like the Army did because you were a crew on a crew.

DK: Yeah.

LM: You just kept your crew. You had somebody look after you when you went in for your meals and so forth in the sergeant’s mess and that sort of thing. But then we had, they told us we were going to evacuate to a port. We had to walk to a port called Memel. That was in the Baltic.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Well, we could hear the Russians firing and so forth and whatever was happening and we decided we couldn’t take all this stuff with us because we’d got quite, as we came out of the camp they were crafty in a way because before we came out of the camp we thought well we’ll not, we won’t leave anything. What people can eat or do so we had Oleo margarine and they were tins about that big. Quite a lot we had of that. And we stood them up and we were throwing these tins at each other. Had the bloody tins stood up. And there was also this klim milk. Now that was really you mixed that up and it would make, you could make a real nice cream of it.

DK: Right.

LM: So we thought we’re not leaving that. So what we’d done I don’t know whether you’d call it carbolic soap. What they used to call Sunlight? You know the old, what they used to wash.

DK: Yeah.

LM: The old ladies used to wash with. We grated that up. We put that in with the milk and we left it there and I reckon the Germans must have, they must have tried that and instead of them getting a nice cream there was this powdered milk. This powdered milk all mixed in with the little grated —

DK: Just soap.

LM: We even powdered up.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Just like the milk so they really couldn’t say look at it and think I ain’t very keen on this. So I, we did pay for it later on. And anyway they marched us to this port called, it was Memel and had to go down in a coal ship. We had to go down this hatch and you left all your, whatever equipment you’d got you had to leave that on the deck.

DK: Yeah.

LM: So we said, ‘We’re not going down there. Not going down a bloody hole in a ship and go through the Baltic.’ They said, ‘If you don’t go down we’ll put the hoses on you.’ And they threatened to hose us with the, they’d got these hoses on deck and so forth so we did actually go down in to the hold of the ship. But there weren’t room to sit. Not to lay down especially. You could just squat.

DK: Yeah.

LM: The trouble was that some of the lads all they had to escape was a ladder, a vertical ladder to this little sort of porthole and some of the lads got a bit of diarrhoea as well because it wasn’t long before the food sort of affected people.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And if they wanted to go to the toilet which a lot did. They couldn’t stomach, some people couldn’t stomach this sauerkraut and things like that so they did have to go to the toilet pretty regular. I was one of the opposite. Absolutely. And anyway, we went to go down in to the ship and away we go and they had what they called the old [unclear] and that was for the mines.

DK: Right.

LM: To ships against mines. We’d already mined that with, with these acoustic they were quite a huge mine. About, they’d be about fifteen foot long.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Twelve, thirteen, fifteen long what we used to drop and that was a bit of a risk because you had to —

DK: So you would actually drop mines in to the Baltic.

LM: Yes. Yeah.

DK: And were now —

LM: I hadn’t dropped them in to the Baltic but I had elsewhere.

DK: Yeah.

LM: The RAF had.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: And they would [pause] they would, that was a bit of a hazardous old job because you had to come down almost to zero feet. You cut your, you dropped your flaps just to sort of give you a bit of buoyancy and you cut your speed down as low as possible. Just above stalling speed. You’d be down to perhaps a hundred and twenty mile an hour and only about two or three hundred feet high.

DK: Yeah.

LM: So if you were lucky you didn’t go over a flak ship but if you did then they could just blow you to smithereens. So that was, people used to say that used to count as a half an op.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But it alright maybe it weren’t because you used to go there, come back and never see a thing.

DK: But you were still on an operation.

LM: You were lucky, you were lucky if you to just get by and —

DK: Yeah.

LM: And never even have anybody fire at you but no, we I suppose the prison camp weren’t too bad and we’d done three seventy odd hours on that boat and you were allowed up on deck one at a time so you could just imagine how long, I don’t know how many I wouldn’t like to say hazard a guess how many were down in the hold of that ship. Hundreds of us. Sitting there. And we came to a place called Swinemünde.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: You’ve heard of Swinemünde have you?

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Have you? Nuremburg was laying there. One of their battle cruisers?

DK: Right.

LM: They took us off the ship and we went, had to get in these cattle trucks and the barbed wire was across the centre of the carriage. You had a half a door, half a door where the prisoners could get in. The other half was for the guards to get in.

DK: Right.

LM: And we had to take our shoes off but what have we got and put them through the barbed wire into the side where the guards were. And then the Germans used to pee in them at night if they didn’t want to get out, couldn’t get out. They used to use them as a toilet.

DK: Wonderful.

LM: And while we were there there was a raid on or supposedly. It weren’t really a raid I don’t think because I learned afterwards that was only one plane and they put a smokescreen over the whole docks and the Nuremberg opened fire on that. It was an American plane, broad daylight and the cattle trucks you could see daylight appear between the wood. Those guns exploding, the vibration we weren’t all that far away from Nuremberg itself.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And so anyway that’s when they took us out from there. They took us across down to a place called [pause] it was quite a way we went. I don’t know the name of the place really. I couldn’t say because they were the same as us. They did block, there were no names on villages or anything like that.

DK: Yeah.

LM: We eventually arrived at our destination and I never heard this. I can honestly say I never heard it. Some of the lads who wrote, if you read the book called, “The Last Escape” they said the Germans, they could tell. They could hear them sharpening their swords, their bayonets. But I didn’t hear it. To be truthful I never heard any. Maybe if I’d heard it I wouldn’t have paid much attention to it anyway. So they unloaded us from the trucks and then made us line up in fives and I’d got this kit bag. As luck would have it I’d got my kit bag. When I got off the boat I’d got this kit bag with my name on and I grabbed that and so I carried that with me and whatever stuff you could carry on your own.

DK: Yeah.

LM: You, or somebody sorted out later on and they loaned us, took off, we come, they lined us in fives. The same old thing again and these, all the guards at that particular time that started off were young Naval lads.

DK: Right.

LM: And we reckoned they came off that they were coming from a Naval dockyard just to see. To escort us to this camp Stalag Luft 4B.

DK: Right.

LM: Not far from Stettin. Well, everybody had got their kit and I stood like that and with the kit bag down the front and this German lad came along and I’ve still got a wound, a star there I think. One of them, he stuck a bayonet in you see. He said, ‘Pick it up. Pick it up.’ So I looked at him and that’s where he stuck the bayonet. As luck would have it it went in to my finger and it came up against my belt. An old hessian sort of RAF belt. Oh. And they had to pick it up and hold it there while we were just waiting. Then they they all —

DK: Your hand’s bleeding presumably at this point.

LM: Very little.

DK: Oh right.

LM: Hardly any blood.

DK: Right.

LM: I reckon it just went right to the bone.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Quite painful. I’ve got a little scar there now which, which you can see some left me a little bit of a scar there. They’re still there today. And they started, we had to march off and it weren’t a march at all. We had to run. Well just imagine they started on the lads up the front and while they carried their kit they kept —

DK: Yeah.

LM: Jabbing. Jabbing. Jabbing, and one lad had over seventy bayonet wounds we counted on him when we got the other end and until they’d dropped their kit they kept sticking the bayonet in and so of course we being quite tail enders we were, it was like steeple chase. And then of course then they got on to us and we, when we started off we’d some little bits and odds and pieces what we’d accumulated.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Picked up here and there. When we got to the camp we’d got absolutely nothing. I’d got a shirt on, trousers, shoes and that was my lot.

DK: And everything else had been lost up the road.

LM: Everything we had to drop.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And they had machine guns all lined up beside this sort of, more or less an old cart track we had to run up and some bright erb at the back was firing a rifle or a, I believe it was the officer with a, with a revolver and we never stopped. Nobody stopped to find out who it was. We just had to run and we actually thought not combined but individually I think ninety nine percent of us thought we would run into a hole. A pit. We did. I did. I thought we was going to be shot because they’d already done that. That had already happened to prisoners. They’d took them and shot them and we again we thought this is what was happening. No one said that to each other. Never said it to each other but afterwards when we got to camp people said, ‘Christ,’ he said, ‘Well, I began to think that’s what was happening.’

DK: Yeah.

LM: And people did but they never spread it because no way would there have been any escape because they’d got machine guns lined up each side of this old dirt track and when we got to the other end I mean that was just, we were just covered in dust. It was in August so it was the middle of the summer.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And there was a fella who used to sleep right next door to me. His name was [Mcilwain]. I’ll never forget him. Well, in, while we were in the camp there was a little Pole and he was watching the Americans at the game of baseball when it was, we played it with a softball. And he was stood around here like that and one of the lads had a whack at the ball and it threw out and it hit him in the teeth and knocked his teeth out. He was a little Pole. Quite a small lad. And when we got the other end of the camp I was with [McIlwain] and [McIlwain] got hit with a rifle butt. And when we got, when we eventually got to the camp this little Pole said, ‘Cor,’ he said, ‘I was knackered.’ The language you used to pick up there. ‘I was knackered,’ he said. ‘But when I saw [McIlwain] get hit with a rifle butt,’ he said, ‘He just went like that and carried on he said, ‘I could have run on for miles.’ So, I mean there was a lot of, there was a lot of —

DK: Humour.

LM: Fun.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I mean, it was a place where you could see the funny side of it but not when, it wasn’t all that funny but later on when you look back.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And anyway, we were at that camp and then we stopped there until February 1945 and then —

DK: How were you treated in the second camp once you got there?

LM: Not badly. Not badly. All our huts were off the ground there. They were better huts.

DK: Right.

LM: And you went up a corridor in the middle and your rooms were off each side. Two, four. Two, four, six, eight, ten, twelve, fourteen. Sixteen in a hut.

DK: Right.

LM: Two there. Two here on each side of the door and they had a tortoise stove and David [Dewlis?] was on the bunk above me and I slept in the bottom one and the lad on the next bunk to me was a New Zealander.

DK: Yeah.

LM: A lovely lad. Long Tom we called him. He was Long Tom. He was about six foot three and he used to sing the Maori’s farewell and a little tear would run down his cheek. Oh yeah. He decided that, he didn’t make a habit of singing it but every now he would sing that little old song. I know the words to that right off. Oh yeah.

DK: I’m quite conscious we’ve been talking for an hour. Do you want to take a break or something.?

LM: I don’t mind. Yes. Yeah. Lovely.

DK: Yeah. Shall we just stop there for a moment?

Other: Yeah. That’s fine.

DK: It’s just I’m rather conscious.

[recording paused]

LM: Fine. Yeah. Yeah. Lovely.

DK: Ok. So I’ll put that back there again. So just to be — talking about the cold weather and the movements.

Other: Yeah.

DK: And prisoners. So just to recap then it’s, it’s February 1945 and you’re in the second —

LM: ’45. Yeah.

DK: And you’re in the second camp and they’re not treating you too badly. What’s happened then?

LM: January. February. They said that due to unforeseen circumstances, they didn’t say why, or why or not, or not we’d got to go. We’d got to move out of the camp and they were going to march us out of the camp. I think we were then what was there, there was somebody else interfering or something was happening and we had to move camp. That was up near Stettin we were and we could see vapour trails. While we were there vapour trails used to go up and we thought they were taking the weather. Apparently, what we were watching was the V-1s and V-2s take off.

DK: Right.

LM: Didn’t know that at the time but going back a little bit I remember a JU88 was fitted with jet engines before ours.

DK: Right.

LM: They had a jet engine fitted to a JU88. No. Yeah 88 not the 87. That was a Stuka.

DK: Right. Yeah.

LM: But the, the eighty eight, yeah. And we weren’t —

DK: You saw one of those fly by then did you?

LM: You could hear them.

DK: Hear them. Right. Yeah.

LM: And see.

DK: Yeah.

LM: You could see them when they came over and you would think that sounds unusual for an aircraft engine and —

DK: Yeah.

LM: And they must have developed that before we did because that was the Germans who brought on the atomic bomb wasn’t it? For the Americans.

DK: Yes.

LM: Their scientists.

DK: Yeah. And the rockets to the moon.

LM: Yeah.

DK: Yes. Von Braun.

LM: Yes. Yeah. And no we were told that we had got to move and we said the treatment we’d had we were not going to go out of the camp. Silly thing to say but there we are. We are not going to move. We are going to stay where we are because we got treated so badly to go to that camp we said we wouldn’t go out of this one and the major, he was an old Prussian. When you say Prussian they were the old Germans weren’t they?

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: And I reckon he was quite an oldish fella. Upright. Real slim, upright. Lovely he was. And he said he would come with us so there would be no ill treatment at all. And we didn’t get ill treated at all. We said we’d come out but the number of people within one or two days had to fall out. Blisters on their feet, had diarrhoea or something like that and my pilot David Josephs, that’s what made me think he was a bit of a politician’s son, he was, David was taken off after a second, I think it was two days he walked with us. After then they had to take him off in the little bandwagon. Whether he went to hospital I don’t know. I never knew. Even when we came home I never knew what had happened to him.

DK: No.

LM: And I kept in touch with him. Oh yeah. We kept in touch. And but at, he was, walked for an hour and we’d have a rest but when you get up again your feet began to tell on you. But that didn’t make no difference to me I’d been so used to talking over rough ground and so forth that didn’t come hard.

DK: Right.

LM: But people used to say, ‘How did you get on with monotonous walking?’ I said, ‘Yeah. What you do, all you do was just look at the persons feet in front.’ And that was just, it was just a tag along behind each other.

DK: Did you know roughly how many people were in this column as you remember?

LM: Oh, I haven’t a [pause] The whole camp.

DK: So —

LM: And there was not just us.

DK: Right.

LM: There were lots of others as well.

DK: So it could be thousands or —

LM: Oh yes. Walking through Germany what they said one morning we got was if you get attacked which there was. I didn’t see any of it to be truthful but some of them were attacked by Typhoons flown by New Zealanders and the idea was half of you would dash. We used to walk through tracks usually. Never, if you went through a village that was occasionally and the funny thing when we went through a village we used to stand up, pull ourselves up and sing and march. And the Germans didn’t like that and the guards didn’t like it either. And then after you got through the village it was like this, sort of striding along but when you walked through a village you put your parts on and started singing. But there was some got shot up.

DK: Did the villagers react to that at all?

LM: They left, the would leave water out but we weren’t allowed to touch it.

DK: Right.

LM: Because there was so much change of water. I don’t think it would have affected me at all.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Because I’d even later on I even drank out of a blasted river and so I don’t but other people it upset very quickly.

DK: Yeah.

LM: People were suffering with diarrhoea and that sort of thing and anyway we started off and a lot fell out. A lot fell out with diarrhoea, bad feet and that sort of thing. And we would have what they called after eight days you’d have a rest.

DK: What happened to those who did fall out and couldn’t —

LM: Took them back to somewhere. Hospital or something like that to give them a bit of treatment I think.

DK: Right.

LM: I couldn’t say. I don’t know what happened to them.

DK: Ok.

LM: I think, well they got back because David he got back.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And we used to write to each other just at Christmas time.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And —

DK: So how long were you on this march for? How many days roughly?

LM: February [pause] And I actually wrote a letter home. Air mail home to my mother on April the 29th. So we were walking from more or less I think somewhere in the middle of February.

DK: To the end of the war basically.

LM: Yeah. February. March.

DK: April.

LM: April. The end of April. But I had, we at the end of the march we had to during the march we could barter sometimes with the farmer. And I had a lovely Van Heusen shirt which had been sent to me by somebody so I swapped this shirt for a kilo of fat pork. Well, we had been walking across Germany with [unclear] and a biscuit perhaps a day. So you can tell what our stomachs were like. They weren’t very lined at all.

DK: Yeah.

LM: They weren’t lined at all.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And I swapped that. I said to Tom and, two of us. Long Tom and Leftie and we’ll fry it down. We’ll cut it into like chips and we’ll fry it down because to eat it as raw meat you couldn’t do that so that’s what we thought we would do. We stuck it in an old klim tin.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Lit a little fire and that night we were in this barn and the old rats would run over you and we got lousy as well. Oh, crikey yeah. And they were, they were big lice as well and we went and curled up and went to sleep. Made a sleeping bag and I used to tuck that right under your head so that no rats or anything could get in with you. And they used to run over you but you used to sort of knock them off.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And squeak and go off ahead and that night we went and [laughs] in the barn and I heard Tom, Long Tom up he got, out he went. The next thing Leftie the other side of me he was gone. And do you know I feel sick. Sick as a [pause] I feel. I’m not being sick I’m not going to. I didn’t buy that stuff to be sick. No way. And I wouldn’t go out. I laid there and I would not be sick. And I thought I’ll imagine I’m drinking a cup of cocoa and I was drinking this cup of cocoa and in the bottom of it was these chips. So it was, it was so awful that had [pause] we had lost all the lining off our stomachs. You passed blood. You would actually pass blood.

DK: So over these weeks then did you have the same German guards or were they changed?

LM: The Germans. Oh, you never knew who was with you.

DK: Right.

LM: Yeah. Some, they didn’t walk all the way with us —

DK: I was going to say —

LM: We would have different guards.

DK: You wouldn’t have different guards all the time then.

LM: Oh yes.

DK: Yeah.

LM: They were all old. Usually the old ones.

DK: Right.

LM: The old Luftwaffe as well.

DK: Right.

LM: And we walked. There was, I think there was something like, yeah, something about four hundred miles we’d done or something similar to that and then they were going to take us back towards the Russians. We’d just come over the River Elbe and I said to my two mates, Long Tom and Leftie, I said, ‘I’m not going back over that blasted river.’ They said, ‘Well, you know, I don’t fancy going back to the bloody Russians the other side.’ So we had said if we see a chance we’ll make a run for it. Well, we were going through this. We always walked through woods, lots of woods off the main track and so forth so we got a gap. ‘Ok, Tom.’ Off we, we ran off. Off we went. Mind you the guards I don’t think they were shooting at us. Never hit us anyway. They was a few shots going off but we carried on running and we came to a river. A little river. It was about as wide as this room and mind you this was time, that was in March time so a bit cold. So we thought if we cross the river, we were playing games I suppose, if we cross the river the dogs won’t be able to pick us up.

DK: Yeah.

LM: But the river was running quite, quite fast and there was little saplings been cut down beside the river so I picked one of these up and I gave it to Leftie and Leftie went across and held this stick you see and chucked one in the water, walked across sideway. So I went across and I held this stick for Tom to hold on to a branch and then come across this what we’d laid in the river. And there was a shot rang out and Tom lost his balance and he went backwards in the river. Got all his clothes on so he got out obviously and we made our way as we thought we had heard of [Saltau?] and that was where the Americans were.

DK: Right.

LM: We thought if we get to the Americans we’d be alright. Well, we got to the edge of a, it was a sort of a spinney we went through and then we came to the finish of the woods was that were open fields. So we stopped there and we decided we’d sort of camouflage ourselves. We’d put a bit of stick in. I had a, I had a German type Africa Corps hat which was a mistake I found out later but [pause] So we put this hat on and I’d got that and somebody knitted it somewhere along the line and we waited until it had got slightly dusk and then we decided we would come out of this little old wood and make our way as we thought towards Saltau. We just came out and we could hardly believe it. We turned left. I can see it even now. Turned, came out of this little wood. We turned left and walked along and we went, ‘Bloody hell.’ There was three blokes laid in the ditch. A little ditch. It wasn’t a ditch as such it was just a dry ditch. Say it that way.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Three Americans err three Australians. Three Australians laid in that ditch just been shot down and they had got escape equipment and everything. But they were also full of beans. Eggs and bacon. So just imagine us three weighing about seven stone and they had just, we’d just walked across Germany. Four or five hundred miles across there and they had just been shot down full of beans. And we walked at night and potato fields, it didn’t matter what was in the way we just walked according to the compass. And I remember particularly we came to a fence of barbed wire. A bit silly. We climbed over the fence of barbed wire. We had to walk across and all of a sudden we started to go in and in and in. Our feet began to get rather mud wet. They come up and I said to the others, I said, ‘Run. For Christ’s sake, run.’ And we ran and we ran through a bloody bog. We didn’t realise how silly we were and we came to another barbed wire, another fence and climbed over that. That was to take the animals out.

DK: Oh. Ok.

LM: That’s what we reckoned.

DK: Yeah.

LM: To keep the animals out of this.

DK: Bog. Yeah.

LM: This bog. We got the other end we took our shoes and socks off and wrang our socks out and they were full of this sort of mud. And anyway we carried on and we used to stop for about have a sort of an hour and then sat down and you would sweat, sweat, sweat when you were walking. Then you stop for five minutes. Ten minutes you’d freeze. Really we were so weak I suppose that, of course the Australians weren’t weak they weren’t weak were they?

DK: I was going to say they were —

LM: They were, oh they were fit as fiddles.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Oh yeah and anyway we, we dodged here, dodged there and carried on and eventually we came up and we heard people in the foreground as we were going in front of us. They were German troops. Walked right into them. So I reckon he was a middle of the range officer and of course they caught us and we had to go over and he looked at us and I reckon he thought what a shower and he gave us some little tablets or sweet or whatever you’d like to call them. They were about an inch long and about a half inch wide and like the old throat lozenge.

DK: Yeah.

LM: Remember the throat one?

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: Well, these were white. I reckon they were vitamin tablets. He handed them out to us and he got the corporal to walk back with us to a little village called Bispingen. And we came back to this little village and that’s where he left us. In a hotel.

DK: Right.

LM: We were put up in this hotel and that night we went out. All six of us went out. We was talking to the German people which was no man’s land then you see.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And we were saying to the woman there, one woman Tom was talking to, he could speak fairly good German and about Saltau, she said, ‘oh,’ this is the honest truth this is, ‘Don’t go. Don’t go to Saltau. The Americans are there,’ she said, ‘They shoot anything that moves.’

DK: Yeah. They still do.

LM: That was a yarn but she said that’s what the Germans said.

DK: Yeah.

LM: She said, ‘Don’t. I wouldn’t go to Saltau.’ So we, we stayed there. Lovely hotel. We weren’t allowed to go upstairs.

DK: So —

LM: We had to sleep downstairs.

DK: So you were put up in a hotel by the Germans.

LM: Yeah. Yeah. They left us there. They didn’t want us. We were, we were a menace.

DK: Do you think the Germans at this point knew the war was lost and it just wasn’t worth —

LM: Yes. Yes, because another time they might have shot us mightn’t they?

DK: Yeah.

LM: And anyway, we were in no man’s land so they were retreating quite badly. And anyway, one particular day the sun was shining lovely. We set outside this hotel enjoying ourselves and there was a German lorry came around from the little village to where the centre of the village was. Another hotel further up the road. Came around the corner. All of a sudden it stopped and out they got and made a dive for it. Couldn’t make much out of it you see. And then I heard this plane and then looked up. There was one Spitfire. One Spitfire just going along. Of course, we, we were from, they knew us.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I mean they weren’t going to shoot us were they? They knew. There was us sitting on the front of this blasted hotel, ‘Oh yay.’ I thought you, daft sods weren’t we? A Spitfire up there never knew who we, I said to Tom, I said, ‘He could have turned around and shot us, Tom. Couldn’t they?’ But no. They were our friends weren’t they? You could see the funny side of it. Ignorant weren’t we? Plain ignorant.

Other: Yeah.

LM: Didn’t care. Anyway, we sat [laughs] they gave us a bowl of soup each day. They made a bowl of soup and there was pork cut into little old squares but they weren’t, they weren’t really all that nourishing. Weren’t all that good. Anyway, we were very pleased with it. And then a young lad came down to us. He said, ‘A Panzer. Panzer. A British Panzer.’ So lovely. Away we go. We ran up and around the corner and thought double double. There was a bloke on a half track or one of these little Bren carriers it was.

DK: Yeah. Yeah.

LM: We had to double up to them. Didn’t know who we were you see because I’d got this blasted African Corps hat on and so, anyway we had to run up to them and he stood there and when he realised who we were and then of course they gave us cigarettes and so forth. But they then put us in the hotel right at the top of the street where we ran to when they was coming in to the village. So the next morning I wrote a letter. One of the Army lads gave me an air mail to write home and that was how I remember the 29th of April when I first wrote home to my mother to say that I was ok. And the next morning they said, ‘Right. The truck will, you get in the truck it will stop twice. The second time it stops you get out and you will go back to the [echelon].’ That’s the depot isn’t it.’

DK: Yeah.

LM: So Long Tom, Leftie and myself. We got in one truck and the three Aussies got in another. So we’re, off we go. Off we go. Funny. Eventually we stopped. The Army lads said, ‘What are you doing here?’ Well, we said, ‘You’ve got to stop twice and we’re going back to the [echelon].’ He said, ‘We weren’t stopping,’ he said, ‘You should have been in the other truck.’ So there’s us three.

DK: Oh no.

LM: We’re on patrol with the blasted Army. They gave me a rifle and put me on a half-track and I thought they said the war was over for us. It doesn’t look much like it. We’re going along the road and they’re firing at bloody copse over the other side. A little old copse there.

DK: Yeah.

LM: I suppose Germans are in. They was firing. These people was firing at something. The lads up the front. So here we carried on. We went, we had a stop at this little village and we weren’t very nice. The Army weren’t very nice.

DK: Do you want me to stop?

LM: Can you turn —? Yeah.

[recording paused]

LM: Yes.

Other: Yeah.

LM: Yes.

DK: Right. So I’ve got it switched back on again. So there we go. We’ll move that there. So you’re now with the British Army.

LM: Yeah.

DK: What’s happened next then?

LM: Well, while we were with them on their, on patrol we got an old vehicle. A little old sort of a Austin 7.

DK: Right. Yeah. Yeah.

LM: In one of these villages and Tom said he could drive you see and we got this thing started. It started up and we were driving around the village in this little motor and we called and went in the shop. It was a baker’s shop. They sold everything I suppose not just bread, they had cakes and everything in there and they couldn’t wait to give us stuff. We weren’t in uniform as such. I mean not really. We were, we were looked like bedraggled bloody gypsies really. I mean just imagine what we were like. Thin as rakes.

DK: Yeah.

LM: And we went in a shop and the German women said, ‘Your bread.’ And the bread we had, the old black bread that weren’t nice at all. That had got a thick layer of Greece on the bottom. But when we, they gave us a loaf of brown bread that was like cake. It was just like cake to eat. Their brown bread. Ordinary brown bread after eating black bread and but anyway we, eventually we got back. They dropped us off and two days we were there on patrol and then they took us back. We got back to the [echelon] and had to go through a de-louser.

DK: Yeah.

LM: DDT. Take all your clothes off. Shave because that’s where the lice grow on and when I came for a medical well first of all they were spraying DDT out of a hose from a container with no masks on. I mean that stuff now. That hangs in people’s bodies. You can’t get rid of it can you?

DK: Yeah. It’s banned, isn’t it?

LM: DDT.

DK: Yeah. It’s banned.

LM: And they were just spraying this all over you, under your arms, everywhere. And I wonder how many people got affected with that. The Army lads were doing it.

DK: It’s carcinogenic. It can cause cancers.

LM: They did all the spraying. Awful stuff.

DK: So its banned now.

LM: But anyway, we had to shave yourself and and the doctor said to me, he said, ‘Ahh,’ he said, ‘Impetigo.’ I said, ‘I don’t think so sir.’ He said, ‘Yes, that’s what I —’ I said, ‘ I don’t think so.’ I said, ‘It’s lice.’ I said, ‘That’s where I’ve scratched myself.’ ‘No. No. No. No.’ So he gave me one of those blue bottles. Years ago you used to get these bottles of blue weren’t they?

DK: Yeah.

LM: From your medical —

DK: Yeah.

LM: Perhaps you don’t remember. You’re not old enough to know that. They were poisonous stuff sort of business. And you’d get them an old blue bottle about that tall. I never used it. I come home and just washed myself. It went. It wasn’t impetigo at all. It looked like it I suppose because —

DK: Scratching.

LM: And you could, the lice was nearly as big as my little nail. They were huge. Just think of them crawling over yourself.

Other: Oh, I feel sick now.

LM: We never had any in the camp though. It weren’t ‘til we came out on the march until we got lousy. There was no lice in the camp whatsoever.

DK: So how did you get back to the UK then?

LM: I came back. We were taken to [Machelen] Airfield.

DK: Right.

LM: Picked up by, they kitted us out with Army clothes then.

DK: Right.

LM: Took all our old, took our old rubbish away and gave us a new Army uniform sort of business and I was picked up on a, I can’t tell you where, I’ve no idea where we actually got to. The airfield we flew from in a Dakota.

DK: Right.