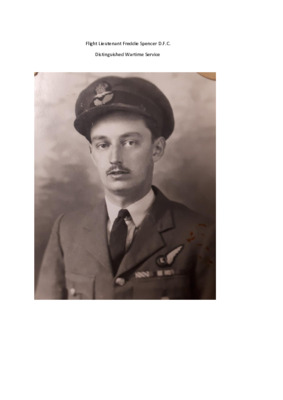

Flight Lieutenant Freddie Spencer DFC

Title

Flight Lieutenant Freddie Spencer DFC

Description

A biography of Freddie Spencer. Details his training and operations with 106 Squadron and 630 Squadron.

Creator

Spatial Coverage

Language

Format

57 printed sheets

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

BSpencerJSpencerFDv1

Transcription

Flight Lieutenant Freddie Spencer D.F.C. Distinguished Wartime Service

[photograph]

Freddie Spencer joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve aged only eighteen on 27 September 1939 at a time when thousands of other young chaps who wanted to “do their bit” were joining up. He signed papers agreeing to serve for the “Duration of the Present Emergency” which effectively was an open ended agreement to serve until either the war was won or until he was killed or disabled and no longer able to serve, whichever the sooner.

He was immediately posted to No. 3 Depot at RAF Padgate as No. 968957, Aircraftman 2nd Class, Spencer FD. There would follow a period of six weeks of “basic training”, his induction to uniformed life, shouting, square bashing, military discipline and all that goes with it. It was a huge sprawling camp organized in quadrants comprising regular rows of barracks interspersed with drill squares and training huts.

[photograph]

Given his civil occupation as a Fitter & Motor Mechanic Freddie was immediately mustered (allocated to a specific trade grouping) as an “under training Flight Mechanic/Flight Rigger” but he still had to do six weeks Initial Training. The RAF had however decided that Freddie had useful skills and that he would receive RAF training to enable him to maintain aircraft. This was an important stage for him because if he had been assessed as less skilled he would have been allocated to a lesser trade grouping where he might be maintaining motor transport or generators, lawn mowers or similar. The alternative was “General Duties”, a category where an Aircraftman 2nd Class would spend his day pushing a broom, painting diverse things or on domestic cleaning duties or maybe peeling potatoes until he managed to escape to a higher grouping hoping to look after several lines of shelves in a stores, run errands, drive a vehicle or work as an admin clerk or officers valet.

[photograph]

Here Freddie is pictured in his RAF issue greatcoat almost certainly in the early winter of 1939.

[photograph]

On 11 November 1939 having successfully completed his “basic” Freddie was posted to No.1 Wing stationed at RAF Hednesford (above and below) to attend the No. 6 School of Technical Training. Here he would begin a course of intensive training on aircraft engines specialising in the Rolls Royce Merlin engine which was destined to power a wide range of RAF aircraft.

[photograph]

Freddie obviously became quite ill within 3 weeks because on 2 December he was admitted to Wolverhampton Isolation Hospital. The duration of his treatment is not recorded but only 2 days later (4 Dec 1939) in his absence he was re-mustered as “Aircrafthand under training Flight

Mechanic” indicating that his progress in training at No. 6 S of TT had been positive and he had been accepted as a tradesman and was now separated from the Rigger trade group (the group who maintained the fuselage and wings, etc) he was to take the path of the more technical aero engine mechanic. Training included both classroom work and hands-on in workshops and was high pressure and intensive, lads who failed to make the grade might be re-mustered to a less demanding trade or even end up as “General Duties”. His annual appraisal on 31 Dec 1939 rated him as having Very Good character and in terms of trade ability he was categorised, under training.

Operational duties

Freddie was posted to RAF Kinloss on 4 April 1940 to join No. 19 Operational Training Unit. At this stage the OTU’s trained men who had recently qualified as aircrew to operate the specific types of aircraft which they would fly when they joined squadrons. Experienced aircrew who had recently completed operational tours were the Instructors and they would pass along the knowledge which they had gained the hard way in combat. Aircrew arrived at OTU from specialist training schools (Pilot, Observer, Air Gunner, etc), and would circulate informally within a large briefing room to form crews. A pilot might recognise an Observer he’d played cricket with and ask if he would like to fly with him, they might hear a Wireless Operator with an accent from back home and ask him to join them, then they would find themselves a rear gunner, etc

No. 19 OTU was a feeder for No. 6 Group, Bomber Command and aircrew attending were trained to fly the already obsolete Armstrong Whitworth Whitley twin engine medium bombers. Freddie would be maintaining and servicing their Rolls Royce Merlin engines.

[photograph]

The Whitley above is the memorial to 19 OUT at Kinloss.

On 6 June 1940 he was promoted Aircraftman 1st Class and re-mustered Flight Mechanic, the promotion was in recognition of his trade skills, now being fully qualified to work on aero engines. On 1 August he was again promoted, this time Leading Aircraftman, recognition of a superior level of technical ability, also indicating that he had the ability to lead and mentor colleagues.

[photograph]

Freddie after his promotion to LAC (see insignia on his sleeve)

[photograph

Freddie’s work on the Rolls Royce Merlins of the Whitley’s flown from Kinloss continued and on 21 November 1940 his mustering was upgraded to “Flight Mechanic Engines” recognising his fully trained status, his ability and the experience he had gained and then on 31 December 1940 in his annual appraisal he was recorded as Leading Aircraftman, Very Good character and his ability was satisfactory (that is a good rating because the RAF demanded the very best performance as a minimum because even slight failings could result in a Whitley crashing or having to be ditched at sea with an uncertain fate for its crew).

[photograph]

The picture above shows RAF flight mechanics working on engines in the normal manner, outside in all weathers. The man sitting upright has the rank insignia of Leading Aircraftman on his arm.

His performance at his duties was recognised and on 22 May he was posted for further training to gain the status of Fitter II Engines, a step which inevitably led to promotion to Corporal rank as an NCO skilled tradesman. Freddie arrived at RAF Hednesford, No. 7 School of Technical Training on the following day and commenced his course.

At the end of his course on 23 July 1941 Freddie qualified as Fitter II E and signalled his intent to leave the Fitter trade group having applied for and received approval to train for the brand new role of Flight Engineer which the RAF had recognised would be essential with the new generation of four engine bombers.

His service record was clearly marked “Recommended for training as Flight Engineer” and on the same day he reverted to the rank of Aircraftman 1st Class. It may have been an Admin ruling in connection with his forthcoming change to aircrew status, it certainly was not a disciplinary, ability or performance related demotion. Quite possibly it happened at his own request for a personal reason, nothing is given in his records to explain. I suspect a brief period of home leave followed.

At this point in the war the RAF had recently started to operate the four engine Handley Page Halifax heavy bomber (photo below) and an understanding was being gained of the very different operational requirements of a four engine aircraft over the traditional twin engine type. A flight engineer was an enormous asset and as the result a 2nd Pilot was no longer required. That freed up a pilot who could then “skipper” his own crew and as the result made available a number of pilots to help replace those being lost on Ops. That RAF had the new four engine Avro Lancaster heavy bombers scheduled to enter service in 1942 and they would each need a Flight Engineer.

[photograph]

Freddie was posted to RAF Baginton near Coventry on 8 August 1941, it was a Hawker Hurricane fighter station and the Hurricanes based there had Rolls Royce Merlin engines. He would be serving with Fighter Command working on Hurricanes until the RAF was ready to start training him as a Flight Engineer, he was not needed in that role immediately.

[photograph

On 4 September he was posted to nearby RAF Honiley to join No. 135 (Fighter) Squadron who flew Hurricanes in defence of the industrial Midlands and on 1 November 1941 he was promoted back to the rank of Leading Aircraftman.

On 4 December Freddie was posted to RAF Angle near Pembroke to join No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron, Auxiliary Air Force a very glamorous squadron with pre-war connections to some of the wealthiest families in the country. No. 615 flew Hurricane fighters. Their CO was Squadron Leader Denys Gillam DSO DFC & Bar a Battle of Britain fighter ace.

The year of 1941 ended very well for Freddie with an appraisal confirming his rank as LAC, his character as Very Good and his abilities as Superior (a rating not commonly seen and suggestive of exceptional ability). The squadron moved to RAF Fairwood Common on 23 January 1942 but almost two months later they moved lock-stock and barrel to Liverpool Docks and embarked aboard merchant vessels bound for India. Freddie was posted at this point, the RAF wanted to make use of his skills as a Flight Engineer.

Aircrew Status

[photograph]

At this point the lack of detail in his service record is most unhelpful. One week after No. 615 departed for India Freddie joined No. 10 Air Gunnery School at RAF Walney Island (photo above) for reasons unstated, however he is depicted in a portrait photograph wearing an Air Gunner brevet.

[photograph]

No. 10 AGS flew Boulton Paul Defiant turret fighters which were obsolete in their intended role as day fighter/bomber destroyers however they mounted a turret with four .303 Browning machine guns exactly like gun turrets on bombers.

It was an excellent gun platform for training air gunners bound for Bomber Command. So it seems that the only conclusion to be drawn is that Freddie trained here as an Air Gunner and was inevitably then classified by the RAF as Aircrew. His service record does not state the fact but I believe it almost certain that he must have been awarded his Air Gunner brevet in the third week of April 1942 before he left No. 10 AGS.

Photo below of a Boulton Paul Defiant painted black for night fighting.

[photograph]

It has to be suspected that Freddie’s training as an Air Gunner at RAF Walney Island was simply a means to an end and that he was never intended by the RAF to fly operationally as a gunner but had gained an Air Gunner brevet and official status of a qualified member of aircrew – perhaps therefore avoiding the requirement to attend a longer aircrew course at a time when Bomber Command had urgent requirement for skilled Flight Engineers.

The twin engine medium bombers operated by Bomber Command up to this point in the war, the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley and Vickers Wellington had been flown by a five man crew including Pilot, Observer (Navigator), Bomb Aimer, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner and Rear gunner.

The new four engine bombers required the addition of a Flight Engineer to assist the pilot on take off and landing, deal with the added complexity of the four engines, manage fuel consumption, etc, and also required an additional air gunner to man the new Mid Upper turret. The new 7 man crew configuration became standard in Bomber Command, a Pilot, Flight Engineer, Navigator, Bomb Aimer, Wireless Operator, Mid Upper Gunner and Rear Gunner.

Freddie was next posted to No. 97 Squadron at RAF Waddington on 24 April 1942. No. 97 was at that moment very much the centre of attention of the nation, having just carried out a seemingly near suicidal daylight raid on the M.A.N. engine factories at Augsburg flying their new Lancaster bombers. Wing Commander John Nettleton of No. 44 Squadron had led the two squadron Op which achieved its aims despite heavy losses. He was awarded a V.C. The attack was viewed on a similar footing to the later Dam Buster raid.

No. 97 Squadron was working very closely with No. 106 Squadron converting from the unsuccessful Avro Manchester twin engine medium bomber (below) to the new Avro Lancaster four engine bombers.

[photograph]

Records of No.97 Squadron do not show Freddie amongst the members of aircrew “posted in” during April 1942 so it seems that he joined purely to gain experience of the new Lancaster, probably working alongside No. 97’s Fitter II E’s and spending time at the factory of A V Roe Ltd alongside the Lancaster production process, this being documented in his service records. Operational records for No. 97 Squadron who were gaining experience of the Lancaster in combat do not show any occasions when he flew Ops in May or June 1942. At this time the squadrons converting from Manchesters to Lancasters were flying with a 2nd Pilot assisting the Pilot due to the shortage of Flight Engineers. Bomber Command did not want two pilots tied up in each aircraft.

On 17 May 1942 Freddie was posted to No. 4 School of Technical Training (RAF St Athan) where he received two weeks intensive training on the duties of a Lancaster Flight Engineer and probably attended lectures by aircrew who had flown aboard Lancasters operationally. He graduated on 1 June 1942 with a Flight Engineer brevet to replace his Air Gunner wing, a re-muster to Flight Engineer on his records and a promotion to Temporary Sergeant as all aircrew received automatic promotion to Sergeant.

Operations – Freddie’s first tour

Freddie was posted to RAF Coningsby to join No. 106 Squadron at a time when they still had some of the troubled twin engine Manchester bombers on their operational strength and the squadron had actually had to operate their newly arriving four engine Lancasters with a 2nd Pilot in each crew because of the shortage of Flight Engineers to help the pilot take off, fly and land the aircraft.

[photograph]

Since March 1942 No. 106 Squadron had been commanded by Wing Commander Guy Gibson DSO DFC (later to be awarded a VC in recognition of the attack by No. 617 Squadron on the Ruhr dams). Gibson had been appointed by No. 5 Group to take the squadron through the difficult conversion to Lancasters at an awkward time. After Bomber Command’s two “Maximum Effort” raids at the end of May/start of June 1942 when every squadron and operational training unit was required to make available crews for all serviceable aircraft in order to get 1,000 aircraft into the air to attack Cologne and then Essen, Gibson was granted a three week time window during which he could put his squadron into a non-operational state. This was to be his single opportunity to get all of his crews trained and familiar with the operation of the new Lancasters which were arriving from the factory of A V Roe Ltd before the next “Maximum Effort” attack was due.

No.106 Squadron at RAF Coningsby

Freddie was one of the Flight Engineers who arrived to join No. 106 during this period of frantic activity of continual day and night time flight tests and training. Later in the war Flight Engineers would have been a part of the crew formation process at Operational Training Unit (mentioned previously), they would have trained within their own crew in preparation for Ops, lived together in accommodation huts, eaten together in the mess and become a very close team prior to being posted to a squadron.

The early Flight Engineers however were completely “dropped in at the deep end”. Crews who had already been flying Ops in Manchesters and the new Lancasters with 2nd Pilot’s were to lose this team member with whom they had been sharing the risks over Germany and instead were allocated a “sprog” (a new member who had little or no combat experience). Surviving veterans reported that in the main the “new bods”, who were regarded as “Gen Kiddies” (technically minded clever chaps) were welcomed into their crews and soon fit in.

Flight Engineers assisted with the Lancaster training process from the moment of their arrival at Coningsby and would be selectively added to crews who were ready to “have a bash” the new way with a “new bod” instead of their tried and tested 2nd Pilot. The 2nd Pilots were obviously needed to “step up” and take on their own crews as Skipper. As a consequence some crews continued to fly with a second pilot, including W/Cdr Gibson who had Pilot Officer Dave Shannon (later DSO DFC, a Dam buster) as his second pilot, while others gradually began to fly with the new Flight Engineers sitting in the “second seat” beside the pilot.

Freddie and the other lads joining the squadron would be serving alongside men who were destined to accompany Gibson on the Dams Raid (ie: David Shannon, “Hoppy” Hopgood, Joe McCarthy, Bob Hutchison, Lewis Burpee, Tony Burcher, Bill Long, Ted Johnson, Guy Pegler) and men who would later lead the Pathfinder and Mosquito marking units, John Searby DSO DFC and John Wooldridge DSO DFC DFM.

[photograph]

An early Lancaster (above)

Squadron records next show Freddie’s first Op.

In the early morning of 25 June 1942 Bomber Command HQ ordered that the night of 25/26 June 1942 was to be a “Maximum Effort” attack on Bremen, a massive port and u-boat building dockyard, it was expected that 1,000 aircraft would bomb the target. Gibson’s window of opportunity to train his crews was over and in common with all other units, No. 106 Squadron was expected to provide every serviceable aircraft on their strength with crews to fly them.

Pilot Officer John Coates RAAF a 30 year old from Queensland, Australia, who had flown previously as 2nd Pilot with Flight Lieut. JV “Hoppy” Hopgood, was allocated Lancaster R5678 and a “scratch

crew” (a crew comprising members of aircrew serving with the squadron but not already assigned to

fly that night as a part of an existing crew). His flight engineer would be Sergeant Freddie Spencer.

During the day they would have followed a standard routine which would be followed before every single Op they flew. The crew would have flown briefly to air-test their allocated Lancaster ensuring that it was serviceable in all aspects and the skipper would have signed acceptance of that fact on the clip board of the NCO who headed the ground crew maintaining that particular bomber.

There would have been an afternoon briefing in which the routes to and from the target were unveiled, usually in the form of ribbons stretching from base across a huge wall mounted map, out across the North Sea towards the target, passing over the target area and indicating the route home. Survivors recalled that very distant targets or targets known to be “hairy” often generated sharp intakes of breath or muttered profanities. Potential searchlight and flak belts along with known Luftwaffe night fighter airfields were pointed out for the Observers (Navigators) to mark on their charts and try to avoid. The wireless op’s were given the call signs and frequencies allocated for the night. Met officers forecast expected weather conditions particularly warning of potential icing on wings which might bring an aircraft down. They also reported any forecast head or cross-winds which might push a crew way off course consuming fuel which may not be spare. Flight engineers worked to calculate and re-calculate the fuel loads based on the required routes, distances to be covered and bomb loads carried. Bomb aimers would pay particular attention to the large scale maps and photographs of the target they could expect to see through their bomb sights, noting landmarks which might be seen on the run up to the target and during the bombing run.

They took off from Coningsby at 23:45 hours and had an uneventful outward flight arriving over Bremen on time with the Main Force, their observer (navigator) Pilot Officer Andy Maxwell, a 28 year old Scot had proven himself proficient. At the post-op debrief John Coates reported that his crew experienced some cloud cover in the TA (Target Area) but Sergeant CJ McGlinn the bomb aimer noted their bombs bursting amongst fires which were believed to be in the town centre. They landed back at base at 04:05 hours. Freddie was doubtless exhausted and would have eaten breakfast in the mess with 24 year old wireless operator Flight Sergeant John Williams from Brentford, 20 year old Sergeant John Dickie their rear gunner, a Scot from Milngavie and 21 year old Stan Topham from Bradford, mid upper gunner before they headed for their beds.

During the day of 27 June 1942 a “Battle Order” would have been posted at RAF Coningsby

indicating that “Ops are on” for the men listed to crew each aircraft specified. Freddie would have

found out that he was again listed to fly with Australian “Skipper” John Coates aboard Lancaster

R5678 as flight engineer for the same lads he had been “crewed up” with to attack Bremen. Bomber crew survivors speaking post-war usually recalled a feeling of relief if (allocated as “spare bods”) they were flying with a crew they had previously flown with and returned safely.

Lancaster R5678 lifted off the runway at Coningsby at 22:45 hours scheduled for a long flight to

parachute sea mines into a minefield known as “Deodars” located in the Gironde Estuary. The RAF regularly planted and re-laid minefields in sea lanes identified as being used by U-boats heading from their bases out to sea, it was a task known by the coded term “Gardening”. A large u-boat flotilla was based at Bordeaux and its concrete pens could not service the u-boats unless they could pass through the Gironde Estuary to and from the Bay of Biscay. Andy Maxwell navigated them precisely to their assigned “Garden” and John Coates report stated that they found “bright moonlight, no cloud and excellent visibility. Five mines were dropped. Slight opposition was experienced near Lorient” (anti-aircraft fire). A safe flight home saw them touch down at 05:05 hours on 28 June and after the routine de-brief it would have been breakfast and bed.

That was the last time Freddie flew with John Coates and crew who were joined by flight engineer Sergeant Tom Reid a 22 year old from Larkhall, Lanarkshire on a permanent basis. Having flown Op after Op they were probably looking forward to the end of their tour but they were caught above

the Ruhr Valley’s Dusseldorf searchlight and flak belt and shot down on 16 August. The entire crew “bought it” - were killed.

Scheduled for Ops again on 2 July Freddie was to fly in another attack on the north German port of Bremen. He would be flight engineer in the crew of 25 year old Pilot Officer Steve Cockbain which consisted of lads like himself who do not appear to have had a fixed crew. They took off in Lancaster R5638 at 23:59 hours and arrived over Bremen to find no cloud and excellent visibility. Their bomb load was released from 13,500 feet and bomb bursts were observed in the docks area causing fire and considerable smoke. Cockbain reported “heavy opposition in the target area” meaning searchlights and substantial flak. They landed back at Coningsby at 04:15 hours.

[photograph]

Above – Lancasters attacking a dockyard/port, searchlights attempting to catch an aircraft while

yellow flak shells burst all around leaving black “smudges”.

After several days rest Freddie was listed on the “Battle Order” of 11 July 1942 to fly with Steve Cockbain and another “scratch crew” in Lancaster R5680. Their target was the u-boat construction yards at Danzig on the North German/Polish Baltic coastline. The squadron took off as usual, each

aircraft a minute or two after the previous with R5680 clearing the ground at 17:05 hours ready for a very long flight. They experienced generator problems over the North Sea and in the vicinity of Denmark (position 56.30 North x 12.00 East) the crew decided to abandon the Op due to aircraft unserviceability and their navigator 36 year old Toronto man Flight Sergeant Fred Spanner RCAF, plotted a course for home. Cockbain landed their Lancaster at base at 23:30 hours.

The “Battle Order” on 31 July listed Freddie to fly again with Steve Cockbain and a scratch crew. They were allocated Lancaster R5742 to participate in an attack on industrial Dusseldorf in the Ruhr Valley (known to cynically to bomber crews as Happy Valley due to its deservedly fearsome reputation for experienced searchlight and flak crews and the hive of night fighters which flew over it). Their navigator would be Fred Spanner again and their wireless operator would be Pilot Officer WJ Buzza

RCAF who had also flown with them on their “Early Return” two weeks earlier. They took off at 01:00 on the morning of 1 August and arrived over the Target Area in cloudless conditions but noting some ground haze. In these conditions the target was located easily and they bombed from 11,000 feet. Cockbain reported that his crew believed they hit a factory in the target area. They were then attacked by a night fighter but managed to evade it. The crew landed back at base at 05:30.

Freddie was not allocated to fly with Dorset man Steve Cockbain again, sadly he would be killed on 14 January 1945 as a Squadron Leader after being awarded a DFC, he is buried at Botley in Oxford. Fred Spanner (later Flying Officer, DFC) was lost on his second tour on 3 September 1943 when his 207 Squadron Lancaster simply disappeared during an attack on Berlin, it was presumed lost without trace over the North Sea.

[photograph]

A squadron of Lancasters preparing to taxi-out ready for take off. (late 1942) Below – Freddie and crew with a 106 Squadron Lancaster

[photograph]

[photograph]

Lancaster crew approach their aircraft (above)

On the night of 8/9 August 1942 Freddie flew his sixth Op, it was to be an important one for him because it would be his last as a “spare bod”, this time allocated to the crew being formed around former 2nd Pilot Sergeant Jim Cassels to fly Lancaster R5680. Cassels had previously flown with Steve Cockbain as 2nd Pilot. They were assigned “Gardening”, to parachute sea mines into a Garden known as “Silverthorn”. It was at a point in the Kattegat off Aarhus used routinely by u-boats. Taking off at 23:45 they flew across the North Sea to find that conditions in the target area were very poor with 9/10ths cloud, poor visability and sea mist. Their navigator located Anholt Island and calculating a precise course and speed placed the Lancaster over its Garden on a “timed run”. Five mines were laid and they returned without incident, landing at 05:45 hours for breakfast.

Regular crew

Following his sixth Op Freddie joined the crew of 33 year Pilot Officer James Leslie (Jim) Cooper a pre-war RAF Regular serviceman (and himself a former Aircrafthand Engineer), who had previously flown as 2nd Pilot with Squadron Leader Harold Robertson (aged 27 from Southern Rhodesia) their Flight Commander. Cooper was assigned to form his own crew after Robertson and his old crew had been shot down and killed two weeks earlier while flying with a novice 2nd Pilot).

Surviving Bomber Command aircrew all say that having a regular crew gave them a sense of belonging, the opportunity to bond, to get used to the habits and nuances of crew mates and to work closely as a team. All said that team work greatly improved the odds for survival.

Jim Cooper and Freddie Spencer flew together for the remainder of their tour. Their regular crew were observer (navigator) Pilot Officer Frank Drew, wireless operator/air gunner Pilot Officer John Buzza RCAF, their regular bomb aimer was Sergeant David Gregory but occasionally they had to fly with various stand-in bomb aimers for reasons not recorded, Sergeants Fred Tucker and H R Bailey made up the crew as mid-upper and rear gunner.

The “Battle Order” for 11 August 1942 assigned Lancaster W4118 to Pilot Officer Jim Cooper and

crew, it’s squadron codes were “ZN – Z” displayed on the fuselage. It would not become their regular aircraft which was R5750, however they had a crew photo taken with it (below) possibly to mark the formation of their own crew.

[photograph]

Freddie Spencer standing 2nd from left, Jim Cooper probably kneeling at left and Frank Drew probably kneeling at right.

The crew’s navigator was Francis Elliott (Frank) Drew a 22 year old Devonport man. Their WOp/AG (wireless operator/air gunner) was WJ (John) Buzza RCAF a 21 year old Canadian, David Bryan Gregory a 28 year old married man from Wallasey was their regular bomb aimer, mid upper gunner was Sergeant Frederick John (Fred) Tucker a 21 year old from Wadebridge, Cornwall and Sergeant H R Bailey was the “tail end Charlie” Rear Gunner.

Seventh Op - first Op together as a crew

Jim Cooper assisted by Freddie lifted Lancaster W4118 off the runway at RAF Coningsby at 23:15 hours on 11 August 1942 and they set course for Mainz. The outward trip was uneventful with their Lancaster arriving over the Target Area to find 5/10ths cloud cover at 3,000 feet, it was a dark night but clear. They bombed from 15,000 feet and reported that bombs could be seen bursting in the built up part of town. Fires were started. Opposition was slight. Bomber Command War Diaries (p.294) notes that considerable damage was caused to the centre of Mainz. After a safe return trip they landed at base at 03:50 hours.

[photograph]

The crew were soon allocated Lancaster R5750, previously flown by the CO, Wing Commander Guy Gibson, the record states that it is pictured in the photo above taken on an attack in late July 1942 by David Shannon.

It was following the attack on Mainz that Jim Cooper’s crew appear to have been assigned their own Lancaster (R5750), this tended to happen in order for an established crew to become familiar with a particular aircraft and its own idiosyncracies. This was a practice enormously beneficial to a crew with a highly competent flight engineer such as Freddie as it gave him the opportunity to know how each engine would perform under operational conditions, to find any ways to eke out fuel if they were low, to look for solutions to high altitude icing and learn any other peculiarities of “his” Lancaster to be able to seek out corrective actions before problems occurred which might kill them.

The “Battle Order” for 27 August named Jim Cooper and crew to fly R5750. No. 106 Squadron were to despatch nine Lancasters to Gdynia a Baltic port 950 miles distant led by Gibson to attack a major warship, the remainder of the squadron were to join the “Main Force” and attack Kassel. The crew took off at 20:50 hours in the force heading to Kassel. The conditions over the target were hazy with no cloud and they attacked from 8,000 feet. Bombs were observed bursting in the town where there were many large fires. Some anti-aircraft fire was noted by Freddie’s crew as were night fighters but they were not attacked. That night 10% of the “Main Force” were lost to fighters and anti-aircraft fire including 5 of the 15 Wellington’s despatched by No. 142 Squadron. All three Henschel aircraft factories were badly damaged (Bomber Command War Diaries, p.303). At Gdynia the warship could not be identified through the haze. R5750 landed at Coningsby at 02:20 hours.

On the following day, 28 August Freddie’s crew were assigned R5750 to participate in an attack on Nuremburg the ideological home of Hitler’s Nazi Party. They took off from Coningsby at 21:10 hours and arrived over the Target Area after the Pathfinder Force had dropped marker flares to assist target acquisition by the Main Force. Jim Cooper’s report stated that conditions were very clear, visibility was good and the target was visually identified. They bombed from 13,000 feet over the centre of the town where too many bombs were bursting for them to be able to identify their own. There was little flak opposition. There was damage recorded in the town centre and to the south the Nazi Party Kongresshalle and parts of the Nuremburg Rally colony was destroyed, (BCWD, page 304). They were fortunate to arrive safely back at base and landed at 04:00 hours, sadly 14% of the British bombers “Failed to Return”.

The pressure on aircrew was maintained with another Op on 1 September 1942. Again flying R5750 Jim Cooper and crew were to participate in an attack on industrial Saarbrucken. David Gregory did not fly on this night and Pilot Officer Don Margach a 30 year old from Edinburgh took his place (Margach was killed on 29 July 1944 flying with 582 Squadron on his second tour). They took off at 23:59 hours and arrived punctually in the Target Area where conditions were clear with no cloud and the Pathfinder Force marker flares were heavily bombed by the Main Force. On this night the flares had been dropped out of place and the nearby town of Saarlouis was battered. Cooper and crew landed back at base at 05:00 hours on 2 September. Opposition had been light as were losses.

After a few hours sleep the tired airmen found that they were again on “Battle Orders” with R5750 to participate in an attack on industrial Karlsruhe that same night, 2 September 1942. Taking off at 23:35 hours they arrived to attack exceptionally well placed Pathfinder flares. David Gregory had been unable to fly with them again and Sergeant J Eastwood flew as bomb aimer. The visibility in the target area was reported as good without cloud. Using the river to identify the target they bombed from 10,000 feet and saw their bombs burst amongst fires in the town which was already burning fiercely. Their successful attack was confirmed by a “bombing photo” (a huge flash assisted camera triggered to capture the fall of the bombs from a particular aircraft and document the point to be hit). Jim Cooper landed at Coningsby at 05:25 hours.

[photograph]

Lancasters over a burning Target Area.

With little opportunity for rest Freddie’s crew were listed on “Battle Orders” again for the night of 4/5 September, they were to participate in an attack on Bremen where the Focke Wulf factory produced aircraft and the Atlas shipyard worked for the German Navy. The recently introduced Pathfinders developed a new tactic and for the first time their initial aircraft dropped “illuminators”

which lit the target area with white flares, their second wave “visual markers” dropped Target

Indicator flares on a positively identified target and their “backers-up” dropped all incendiary bomb loads on the coloured flares. This practice continued for the remainder of the war and allowed the Main Force to bomb more accurately. (Bomber Command War Diaries, p.306).

Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew aboard Lancaster R5750 took off at 00:30 hours on the morning of 5 September and arrived over the Target Area to find the weather very good and identified the target easily but due to the heavy smoke from many fires already burning they couldn’t see details. Bomb aimer Sergeant Eastwood was flying with them again and he bombed from 11,000 feet and was able to note the bursts of their bombs through the smoke. Flak was very heavy and accurate and their aircraft received hits and battle damage. They made it home safely landing at 05:30. Both the aircraft works and the Atlas shipyard were seriously damaged.

On the night 6/7 September Freddie’s crew were assigned Lancaster R5900 for the attack on Duisburg, their own aircraft was still under repair. They took off at 01:25 hours, again Sergeant Eastwood flew as their bomb aimer, and finding ground haze across the target they struggled to pinpoint the target. Locating the River Rhine Jim Cooper followed it and aided by Pathfinder flares they bombed from 11,000 feet seeing bombs bursting in a built up area 1 mile east of the river. As might be expected of a centre of heavy industry the flak opposition was intense. The crew noted fires burning well before they turned for home. Theytouched down at 05:15 hours.

Battle Orders for 8 September included Freddie’s crew – the target was industrial Frankfurt. Jim Cooper had been assigned the repaired R5750 and their own bomb aimer David Gregory was to rejoin them. They lifted off the runway at Coningsby at 21:00 hours. Haze over the target area made locating the aiming point difficult but finding an identifiable bend in the River Main Gregory made a bombing run and they attacked from 11,000 feet. Bombs were seen bursting in the estimated centre of the town. Little opposition was experienced, although searchlights were active the flak was light. They returned to base at 03:10 hours on 9 September.

It was the same story for the night of 10/11 September, allocated their own Lancaster R5750 Freddie and crew took off at 20:55 to take part in an attack on the factories of Dusseldorf. There was no cloud in the target area but visibility was not good due to haze. They bombed from 12,000 feet based on a timed run from a fix point. No bomb bursts could be seen however their “bombing

photo” was very good and showed that they had hit a cluster of factory buildings. Bomber Command War Diaries p.308, records that substantial damage was caused to 39 factories in Dusseldorf and Neuss sufficient to halt all production for several days. Sadly 33 of the bombers were shot down, 7% of the force. The crew landed safely at Coningsby at 01:30 hours.

The next raid of any size into the Ruhr Valley was on the night of 16/17 September when 369 bombers were ordered to bomb the Krupp tank production factories at Essen. Freddie was likely unhappy that R5750 was not serviceable and their crew were assigned a spare, Lancaster W4195. The complete crew were flying again and Jim Cooper lifted the Lancaster off at 20:25 hours. Over the target they experienced 5/10ths cloud, poor visibility and were unable to locate the ground detail which were preferred for good accuracy. Their bombs burst in a built up district as was

confirmed by their “bombing photo”. In the traget area they were buffetted by fierce and very intense flak and noted a series of bombers being shot down. The Krupp factories were damaged by bombs and by a fully loaded bomber which had been shot down and crashed directly into the target.

[photograph]

The Krupp Panzer factory following RAF bombing (above)

Although successful the attack on Krupp cost 39 bombers, over 10% of the force despatched. Landing at 01:35 hours Freddie and his crew were to discover that 3 of the 11 aircraft of No. 106 Squadron which had flown that night had “Failed to Return”, their flight commander 25 year old Devon man Squadron Leader Cecil Howell and his crew and those of Pilot Officers Downer and Williams. The latter crew disappeared without trace and included Flying Officer Bob Chase (Gunnery Leader) who had flown with Freddie aboard Steve Cockbain’s Lancaster on the night of 31 July. The loss to No. 106 was very heavy but in the eyes of its crews probably not unexpected, the flak

gunners in “Happy Valley” caused heavy losses and it was regarded as a “heavy chop” target.

No. 106 Squadron were tasked to contribute aircraft to a small force to bomb Munich, the headquarters of the Nazi Party, on 19 September. Lancaster R5750 was serviceable again and the entire crew were listed for Ops. Taking off at 20:10 hours they began the long range trip and arrived over target to find no cloud and good visibility. David Gregory located the aiming point without difficulty and they bombed at 8,500 feet noting bombs bursting across the town. Flak was slight and the trip marked as very successful when they landed at 04:10 hours on 20 September. Only six of the 68 bombers attacking were lost.

“Battle Orders” for 23 September called Freddie’s crew to fly their trusty Lancaster R5750 and attack the Dornier aircraft works at Wismar as a part of a small force of 83 bombers. Jim Cooper took off at 22:40 hours and over Wismar on the Baltic coast they found 10/10ths cloud cover and were unable to identify the target despite low passes over the vicinity. David Gregory was not flying that night and another bomb aimer, Warrant Officer N Manton, made his bomb run based on calculations and timing. Attacking from 1,500 feet they did not see the results although other aircraft noted large fires including a massive fire in the aircraft works. All crews experienced intense flak and searchlights and balloons were present over the target. Many aircraft were damaged and 4 shot down. The crew landed back at Coningsby at 06:30 hours.

Given a week to rest Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew were again scheduled to fly R5750 on 1 October to return to Wismar. With the full crew together again they took off at 18:20 hours but out over the North Sea experienced serious engine problems and had to return to base at 19:30 hours.

The next night, 2 October 1942, Freddie’s crew were on “Battle Orders” again, they were assigned R5750 to attack industrial Krefeld. Jim Cooper took off at 19:00 hours and after an uneventful outward flight they encountered dense haze in the target area, the Pathfinder Force were late to mark the target and David Gregory bombed from 14,000 feet through considerable ground haze but reported that the incendiaries seemed to start a fire in a built up area, he was almost certain that they had hit their target. They landed at base at 00:25 hours.

The attack on Aachen of 5/6 October 1942 started badly as bomber squadrons took off from their bases in heavy thunder storms, six aircraft crashed in England before they had reached the Channel. Lancaster R5750 was manned by Freddie’s complete crew and they fought the weather all the way to Aachen which was located in 10/10ths cloud at 12,000 feet. Visibility was fair lower down and they attacked from 11,000 feet and observed explosions in a built up area. There was some flak but they were not close to it. 4% of the attacking bombers were lost that night.

No. 106 Squadron moved its base in October 1942 transferring from RAF Coningsby to RAF Syerston in Leicestershire. At about this time Frank Drew their navigator was promoted to Flying Officer, this was doubtless celebrated in true RAF fashion.

After a break and possibly a period of leave Jim Cooper, Freddie and their complete crew were back on the “Battle Order” of 22/23 October 1942 for a No. 5 Group special operation. The crew were to participate in a very long range Op to bomb Genoa in Italy, an attack timed to coincide with the Eighth Army (Desert Rats) attack at El Alamein. Freddie must have been annoyed to find that R5750 was unserviceable when they did their afternoon flight test. They took off in an unfamiliar Lancaster W4763 at 18:05 hours for the very long flight to the target. Conditions over Genoa were clear with no cloud and bright moonlight. Several pinpoints were identified and then Pathfinder flares were seen. The 112 Lancasters bombed, David Gregory attacked from 10,000 feet directly onto the target and bomb bursts were seen in the town centre. Bomber Command War Diaries, p.18 reports that the small force carrying only 180 tons of bombs lost none of its aircraft and caused very heavy damage in the city centre which proved seriously demoralising to the Italian people. At least one Lancaster roared across the city just above the roof tops machine-gunning targets of opportunity.

The crew landed back at RAF Syerston at 02:45 hours.

At this point crews of No. 106 Squadron had started to receive certificates for attacks on more risky targets, this is believed to have been a No. 5 Group practice. Freddie and his crew received one.

[photograph]

To keep up the pressure on the Italian Homefront No. 5 Group were tasked with a risky daylight attack on Milan. The order called for 88 Lancasters to proceed independently by a direct route across France using some cloud cover to rendezvous above Lake Annecy before crossing the Alps and bomb Milan in broad daylight. Back in their Lancaster R5750 Freddie’s crew lifted off at 12:40 and arrived over the target to find good visibility and cloudbase at 5,000 feet. They bombed at 4,500 feet after easily locating the target and saw their bombs bursting in town near the electric works. Soon after the air raid sirens started. There was considerable light flak but it was not accurate. Only 4 Lancasters failed to return.

The photo below shows airmen of No. 106 Squadron who had attacked Genoa on 22/23 Oct 1942.

[photograph]

A night raid took place on Genoa on 6/7 November 1942 when Jim Cooper and crew flew without Freddie, the reason for his absence is not given.

The “Battle Order” for 9 November called for Freddie and the crew to fly Lancaster R5750 to bomb Hamburg. The complete crew took off at 17:40 and had a difficult outward flight in very poor weather fighting strong winds. They encountered severe icing throughout. Locating the target was difficult due to 10/10ths cloud and they bombed a secondary target Roclinghausen from 14,000 feet. It was believed that their incendiaries caused fires to break out. They landed back at Syerston at 00:35 on 10 November.

At this point No. 5 Group HQ were requested to put pressure back on the Italians and although that inevitably involved arduous long range operations they scheduled the aircraft and crews to accomplish this.

On the night 13/14 November accompanying several Pathfinder markers 67 Lancasters attacked Genoa again. Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew took off in Lancaster R5750 at 18:00 hours following their new flight commander Squadron Leader John Searby (later one of the greatest of the Pathfinder leaders). Conditions in the target area were clear with good visibility and David Gregory had the target in his bomb sight when he bombed at 9,500 feet. Their bombs burst across the target area starting fires. Flak was reportedly minimal. They landed back at base at 03:05 hours.

[photograph]

Another attack on an Italian target followed on 18/19 November this time led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson and Squadron Leader John Searby. Aboard their faithful R5750 Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew took off from Syerston at 18:00 hours to attack the Fiat motor works at Turin. Excellent conditions for bombing were found above the target with the factories clearly identified they bombed from 9,500 feet with at least two of their stick of bombs hitting the target factory. Flak was encountered but nothing like that of the Ruhr Valley. The crew were assisted by favourable winds on their homeward trip and landed at 01:15 hours just as Gibson and Searby were preparing to land.

[photograph]

The night of 20/21 November called for the crew and their reliable Lancaster R5750 to undertake another long range Op to attack the Fiat works at Turin again, they were part of the biggest raiding force to Italy at that time, 232 bombers. Jim Cooper took off at 18:40 hours and on the route out one engine inexplicably failed. Freddie was unable to effect repairs in flight and despite the huge challenge the crew decided to continue, they made the rendezvous and crossed the Alps fully laden with bombs on just 3 engines. There was no cloud over Turin on arrival but the target was masked by a thick ground haze and smoke from the town. Frank Drew and David Gregory managed to pinpoint a road and river junction which enabled a timed bombing run. No results of the attack were visible but later intelligence reported heavy fires. Freddie managed to coax enough power from their three remaining engines to get them back over the Alps and they returned on three to land at 03:10 hours.

After a week of rest to recover from the long flights Freddie’s crew must have pondered their luck to be on the “Battle Order” of 28 November, another long range attack on Turin. Wing Commander Guy Gibson and Flight Lieutenant Bill Whammond led the No. 106 Squadron element and these two officers dropped the first two 8,000 lb bombs on Italy. This time Freddies crew took Lancaster W4770, taking off at 19:00 hours, they crossed the Alps without trouble and found the conditions clear over Turin, visibility was good and there was already some smoke over the target as several crews had attacked immediately on arrival instead of awaiting the Pathfinders. David Gregory bombed at 7,000 feet with the target in his sights. Their bombs were observed to burst and start fires, many large fires were seen and the bombing regarded as accurate. The crew landed back at RAF Syerston at 03:00 hours. In the course of this attack the Australian skipper of a No. 149 Squadron crew (F/Sgt R H Middleton) earned a posthumous V.C.

Following several days rest Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew were listed on “Battle Orders” again, for 6/7 December 1942 to participate in an attack on Mannheim in Germany in R5750. Taking off at 17:30 they arrived to discover Mannheim masked by 10/10ths cloud, their target was unidentifiable. Working on navigational reckonnings they bombed from 10,000 feet and although unable to see their bombs burst, fires could be seen burning beneath the cloud cover. They landed at 00:30 hours.

Last Op of the tour

At this stage the crew were near to the end of their tour and due to be “screened from Ops”, (removed from the roster of crews liable to be placed on “Battle Orders”) and due to be posted away. If they were able to complete their last Op they would have survived their tour.

On the night 8/9 December 1942 Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew were assigned Lancaster W4256 for yet another long range Op to Turin. They took off from RAF Syerston at 17:35 shortly before their flight commander Squadron Leader John Searby and headed directly for the Alps. Arriving over Turin they discovered clear conditions, and good visibility despite a smoky haze. The target could be clearly identified and it was bombed from 6,000 feet. The crew noted their bombs bursting near a bridge 1000 yards south east of the primary aiming point and after circling the target for 18 minutes to recconoitre they headed home and landed at 02:20 hours.

[photograph]

Jim Cooper, Freddie and crew had survived their tour of Ops with No. 106 Squadron.

[photograph]

As was quite normal, the Skipper, Pilot Officer James Leslie Cooper (111552) RAFVR was recommended for a Distinguished Flying Cross in recognition of the success of his crew in their tour of Ops. Navigator - Flying Officer Francis Elliott Drew (104411) RAFVR was recommended for a DFC shortly afterwards and finally received it in March 1943.

The remainder of the crew were not decorated at that stage as was entirely normal: (Flight Engineer) 968957 Sergeant Frederick David Spencer RAFVR.

(Bomb Aimer) 1310664 Flight Sergeant David Bryan Gregory RAFVR. (Wireless Op/Air Gunner) Pilot Officer W. John Buzza, RCAF.

(Mid Upper Gunner) 1313519 Sergeant Frederick John Tucker, RAFVR (Rear Gunner) Sergeant H R Bailey (as yet not positively identified)

Most of the crew were posted-away to instruct at training units where they would prepare airmen about to embark on their own first tour of Ops. Freddie left No. 106 Squadron in late December 1942 posted to Instruct.

Jim Cooper, Frank Drew and Fred Tucker met up again to fly their second tour at No. 619 Squadron later transferring to No. 617 Squadron together. They were flying in a Lancaster attacking Munich on the night of 24/25 April 1944 when it was shot down by a night fighter, fortunately these three men managed to bale out and survived the war as Prisoners of War.

Freddie’s crew:

James Leslie Cooper DFC died in January 1982 in Scunthorpe.

Francis Elliott (Frank) Drew DFC died on 25 Jul 1957 in Paignton, he had married in June 1943 and had a son.

WJ (John) Buzza RCAF rendered distinguished service to Canada in the RCAF post-war (he was promoted to Wing Commander and after the reorganization of the Canadian Military he retired as a Brigadier General with the Canadian Decoration (C.D.)

David Bryan Gregory died in Queensland/Australia in 2008 having emigrated with his wife and five children in 1958.

Frederick John (Fred) Tucker married in June 1944 later having 3 sons and a daughter, he died in October 2003 in Wadebridge.

H R Bailey may have been a Canadian who was killed later on Ops in mid 1944 flying with 57 Squadron, I have struggled to positively identify him.

A period of “Rest” - instructing and still flying Ops

Theoretically Instructing was “resting” as it was not expected to involve operational flying. However instructing “sprog crews” (inexperienced) was seen by the tour-expired operational airmen as a pretty dangerous occupation given the number of crashes which occurred.

Freddie joined No. 1654 (Heavy) Conversion Unit at RAF Wigsley on 22 December 1942. The unit existed to accept aircrews from Operational Training Units (OTU’s) where they had learned to fly aircraft such as the Short Stirling and Vickers Wellington and sometimes Avro Manchesters and re- train them to fly Manchesters and Lancasters.

[photograph]

A Lancaster of No. 1654 CU (1943/44)

During January 1943 Bomber Command HQ expected every RAF unit to make available aircraft and crews to bomb Berlin and No. 1654 HCU provided a number of crews which were most likely centred on tour expired aircrew serving at the unit as instructions but each likely including some of the men who were there to learn.

It is certain that this happened on the night of 17/18 January 1943 because No. 1654 CU operating from RAF Swinderby lost two of those it assigned (Lancasters R5843 and W4772) flown by Pilot Officer F A Reid DFC and Pilot Officer L Jenkinson) and sister unit No. 1656 HCU lost Lancaster ED316 flown by Flight Lieut. S D L Hood RNZAF. It is likely that many more flew and returned safely, possibly in other nights in Jan 1943 as well. It would be surprising if Freddie had not flown one or two Ops during this period, supervising a novice crew.

Instructing would have continued and the crashes began. Freddie witnessed many. On 24 Jan 1943 one of the units Manchesters force land just outside Lincoln with an engine in flames, on 25 Feb a practice bomb exploded beneath a Manchester and destroyed it, on 2 March a Manchester crewed by one of the experienced pilots F/Lt P J Stone DFC flying with a novice crew hit a tree, one man was killed and all others injured.

On 4 April one of the unit’s Manchesters was reported destroyed by fire.

Based on his performance Freddie had been recommended for a commission and on 4 April 1943 he was formally discharged from service in the RAFVR as an airman and commissioned into the RAFVR as a Pilot Officer (issued an officer’s service number 143793). He remained at his Instructing duties with the Heavy Conversion Unit.

Just days afterwards on 8 April one of their Lancasters (L7545) with a novice crew under instruction from one of Freddie’s peers (Pilot Officer J H Wolton DFM a fellow Flight Engineer Instructor) was in collision with an Oxford training aircraft at 18:15 hours. Both aircraft crashed at Burton Lazars in Leicestershire. All eight crew aboard the Lancaster were killed.

The toll continued for No. 1654 HCU on 15 April when a Manchester crashed and burned near the airfield, fortunately the crew of seven survived but all were injured, on 7 May the undercarriage of another Manchester collapsed during take off causing a belly landing and on the night of 23/24 May one of their Lancasters (W4303) on a night training flight broke up in the air east of Hull killing the crew of eight (including an instructor). On 11 June their Lancaster ED833 crashed after its wingtip clipped a telegraph pole, the rear gunner survived injured but his six crewmates were killed.

On 27 July Lancaster ED591 crashed while taking off when a tyre exploded and the inexperienced pilot was unable to take corrective action. The crew walked away on this occasion. August 1943 was almost an entire month without No. 1654 CU suffering a serious accident until 31 Aug when on a late evening flying exercise Lancaster W4260 crashed after a mid-air collision, the crew fate is not recorded. Later that night another of their aircraft, Lancaster R5698 collided with another training aircraft and crashed killing its crew of seven.

On 17 Sep Lancaster W4921 crashed as its novice crew took off, they were fortunate to walk away.

At this point Freddie’s work as an Instructor was recognised and he was promoted to Flying Officer (8 Oct 1943).

On 22 Oct Lancaster L7575 with a full crew crashed due to turbulence and icing and all seven airmen were killed and on 11/12 November the novice pilot of Lancaster W4902 on a night exercise crashed while taking evasive action to avoid another aircraft. The HCU crew suffered 3 killed and 3 injured.

It is suspected that Freddie might even have been relieved to be posted from No. 1654 Heavy Conversion Unit on 20 Nov 1943, he was to re-join an operational squadron as Instructor. No. 630 Squadron was a brand new squadron in the process of forming at RAF East Kirkby.

Freddie’s second tour of Ops

Freddie was posted to RAF East Kirkby on 20 November 1943 with the rank of Flying Officer to serve as a Flight Engineer Instructor however his orders were quickly changed to meet operational requirements and he was promoted again on 1 December 1943 to Acting Flight Lieutenant.

[photograph]

On Freddie’s arrival at East Kirkby No. 630 Squadron was 5 days old, Squadron Leader Malcolm

Crocker DFC a 26 year old American from Massachusetts was forming it from “B Flight” of Wing Commander Fisher’s No. 57 Squadron based on the same airfield. Bomber Command were following a similar practice on many local air bases, they needed more squadron’s formed around experienced cadres to keep up the pressure of German war industry and strike hard particularly against Berlin.

Crews were posted in from other No. 5 Group squadrons such as No. 9, No. 44, No. 61, No. 106, No. 207 and No. 619 and were supplemented by new crews from HCU’s until the squadron reached strength. Conditions were tough, accommodation was not completed and much of what was needed to make a squadron operational was not available.

Freddie had been appointed Flight Engineer Leader by Malcolm Crocker, he was to head up all of the Flight Engineers assigned to the squadron. His responsibility was to ensure the operational and technical competency of every Flight Engineer. His duties would also extend to their personal well being, health and discipline. In the air each flight engineer reported to his Skipper who shared responsibility with Freddie, but on the ground, on and off duty, on leave or in hospital they were

Freddie’s engineers. He held lectures and shared his experience with his engineers.

The ”Departmental Leaders” such as Flight Engineer Leader, Gunnery Leader, Bombing Leader, Signals Leader, etc, were all experienced men, all led by example and all of them flew on a regular basis sharing the operational risks with their men. Malcolm Crocker the officer forming the unit and interim CO did likewise until the permanent CO was due to arrive mid December, Wing Commander John Rollinson DFC.

The squadron was almost immediately expected to provide operational aircraft and crews and somehow managed to achieve that. They participated in attacks on Berlin on 18/19 November, 22/23 November and 24/24 November. On the latter night No. 630 Squadron suffered its first losses when two Lancasters “Failed To Return”, twelve of the fourteen aircrew were killed including two of Freddie’s flight engineers, 20 year old Sergeant Norman Goulding and 21 year old Sergeant Charlie Pell. Ops continued at a rapid rate, bombing Berlin and Leipzig, another two crews were lost in early December with one single survivor. Within those crews Freddie lost two more flight engineers 19 year old Sergeant George Crowe and 22 year old Sergeant George Leggott. And the attacks on German cities continued throughout December.

The new CO arrived during the month, he was a highly experienced officer who had led bombing attacks on Italy and enemy shipping from besieged Malta. A potential replacement for Squadron Leader Malcolm Crocker also arrived as he was due to transfer away to command his own squadron with promotion to Wing Commander (Crocker died in June 1944 leading No. 49 Squadron), the new officer was Squadron Leader Ken Vare AFC. To familiarise himself with the current operational practices Wing Commander Rollinson flew two Ops as 2nd Pilot to Malcolm Crocker and on the night of 1-2 January 1944 Squadron leader Vare did likewise, flying with the experienced crew of Flight Lieut Doug MacDonald DFC.

The night bombing war against Germany was even more dangerous than it had been in 1942 when Freddie was last on Ops. Colonel Josef Kammhuber who headed the German night air defence system had almost perfected the cooperation between German ground radar installations, searchlight and flak belts and both radar equipped night fighters and single engine night fighters some

directed from the ground and some free to roam in “busy” areas. The “chop rate” experienced by

bomber crews was climbing.

[photograph]

A flight engineer at work, sitting beside the pilot in the cockpit of a Lancaster bomber.

Operations again

[photograph]

Lancaster at night, engines running up, preparing to go.

The night of 1 -2 January 1944 was to be another major attack on Berlin and No. 630 Squadron was to provide 15 Lancasters. The experienced crew of Flying Officer Ken Ames DFC, formerly with 61 Squadron, had just lost its flight engineer through medical problems and were probably highly

cautious of commencing Ops quite late in their tour with a newly assigned “sprog” flight engineer, it is understood that they were delighted to find that the Squadron Flight Engineer Leader, Freddie Spencer, was going to fly some Ops with them.

Ken Ames, Freddie and crew lifted off from RAF East Kirkby at 23:50 hours in Lancaster JB654 “C for Charlie” and began the long outward leg of their Op to Berlin. In the target area they encountered 10/10ths cloud cover. The Pathfinders marker flares were unsuccessful and bombing would have been highly inaccurate if it were not for the ground scanning radar H2S which enabled a fix. They bombed Berlin and returned safely to land at 07:39 hours.

One of their crews failed to return, it included the new Squadron Leader Ken Vare and another of

Freddie’s flight engineers, Sergeant Bob Smale aged 21.

Freddie was to fly as Flight Engineer in Ken Ames crew on a regular basis.

Ken Ames was a 22 year old from Wandsworth in London who had learned to fly as part of the Air Training Scheme in the USA. The navigator was 22 year old Jim Wright , 35 year old Sergeant Tom Savage was bomb aimer, Australian Flight Sergeant Harvey “Tex” Glasby was their 23 year old wireless operator/air gunner, Irishman Sergeant Bill Leary flew as mid upper gunner and 25 year old Dubliner Sergeant Richard (Paddy) Parle DFM as rear gunner.

[photograph]

In the picture above (standing left to right) Tex Glasby, Ken Ames, Paddy Parle, Freddie Spencer, 2 ground crewmen. (squatting left to right) 2 ground crew, Jim Wright, Bill Leary, a member of ground crew, Tom Savage.

At this point in his wartime career Freddie had the option to only fly once or twice every month but he chose to put himself on the “Battle Order” almost every single time Ken Ames crew was assigned and flew through the thick of a period of terrible losses setting an extremely high standard of courage.

The following night 2/3 January he took off in Lancaster ND338 “Q for Queenie” flown by Ken Ames at 23:39 hours, again bound for Berlin. Over the target area there was blanket cloud cover but they observed the flash of the exploding 4000lb “cookies” beneath the cloud as they bombed. Intense flak was experienced and the most active night fighter defences noted to date. Freddie’s Lancaster was targeted by three different night fighters and during the ensuing battles and evasive actions the gunners used up virtually all of their ammunition. A single engine Messerschmitt Bf109 Wilde Sau night fighter was reported hit and damaged, a Junkers JU 88 twin engine radar equipped night fighter was also hit and damaged and a twin engine Bf 110 night fighter was badly hit and possibly destroyed. The crew landed back at East Kirkby at 07:54 hours.

[photograph]

Although Freddie’s Lanc wasn’t hit itself on the above occasion this illustration shows a Lancaster under attack, its gunners returning fire at a nightfighter while the pilot is taking evasive action.

On the night 5/6 January 1944 Freddie again flew with Ken Ames crew this time aboard Lancaster JB672 “F for Freddie” to bomb Stettin on the Baltic coast. They took off at 23:43 hours and arrived over Stettin to find 2/20ths cloud at 18,000 feet and reasonable visibility. Attacking they noted a large explosion at 03:50 with the docks area and town both being hit. A trouble free trip home saw them land at 08:56 hours.

“Stood down” from Ops for several days due to weather and moon conditions the squadron began training, Wing Commander Rollinson took some leave and Squadron leader Edward Butler DFC & Bar the “A-Flight” commander took temporary command.

On 21/22 January Berlin was the target again, Freddie put himself on “Battle Orders” to fly with Ken Ames and crew, they were allocated Lancaster ED335 “L for Love” and took off at 20:14 hours.

Struggling with engine troubles they were unable to gain height or get up speed properly so they attacked Magdeburg which was the target of another part of the force that night, bombing on a series of red and green pathfinder markers. They were the last to land when they arrived home at 03:14 hours and yet again one of their crews was missing. Six of the seven men aboard had been

killed including one of Freddie’s stalwarts, 33 year old Sergeant Bill Yorke.

Berlin was the target on the night of 27/28 January and Freddie again opted to fly with Ken Ames and crew, they took off in Lancaster JB290 “D for Dog” at 17:36 led by Squadron leader Roy Calvert DFC the new flight commander. They arrived in the target area early and noted that the Germans had lit dummy flares to the south west in an attempt to confuse the RAF bombers but the Pathfinder flares of the correct type and colours soon landed on target and they bombed from 19,500 feet. Ken Ames landed back at East Kirkby at 01:51 hours.

Allowing himself no rest Freddie put himself on “Battle Orders” again the following night to accompany the crew to Berlin again. The night attach of 28/29 January 1944 led by Wing Commander John Rollinson was to have heavy consequences for No. 630 Squadron. Aboard

Lancaster ND335 “L for Love” which was serviceable again, Ken Ames, Freddie and crew took off at 23:45 to head for “the Big City”. At 03:29 hours at 22,000 feet “L for Love” was attacked by a Junkers JU88 twin engine radar equipped night fighter. Paddy Parle in the rear turret noted his approach and instructed skipper Ken Ames to corkscrew (roll over diving steeply and continue turning) as he returned fire. The enemy fighter broke off its attack and was not seen again. Nearing the target area they could see concentrated fires burning in Berlin which they attacked, bombing in the target area and returned without further difficulty landing at 08:01 hours.

It was soon realised that two of their Lancasters had “Failed To Return”, Wing Commander Rollinson

and his entire crew had been killed as had the crew of Pilot Officer Bill Story RAAF. Two more of

Freddie’s flight engineers were not there to eat their “post Op” breakfast, 19 year old Sergeant Percy Kempen and 23 year old Sergeant Doug James.

[photograph]

Lancaster attacked over the burning target area by a radar equipped twin engine Junkers JU 88 night

fighter armed with “Jazz music” vertically firing heavy cannons.

On 2 February Freddie was confirmed in his appointment as Flight Lieutenant and sent on the Engineer Leader Course at No.4 School of Technical Training (RAF St Athan). Three months late Bomber Command had recognised that Engineer Leaders could not just been dropped in at the deep end and belatedly set up a course to give their Flight Engineer leaders, at that time the senior ranking operational Flight Engineers in the RAF, the tools that they would need to continue doing their jobs.

Freddie would have left his flight engineers in the care of his deputies Flying Officer Bill Mooney DFM lead flight engineer in “A-Flight” and Flying Officer Joe Taylor DFC, lead flight engineer in “B- Flight”.

A few days after Freddie commenced his course at St Athan the new CO of No. 630 Squadron Wing Commander Bill Deas DSO DFC & Bar a 28 year old South African arrived at East Kirkby to take command. He would have met Freddie on his return from St Athan on 1 March 1944. Five crews had been posted missing during the time he was on the course and of the 35 aircrew, only five had survived, only one of them was a flight engineer.

The first time that No. 630 Squadron was flying Ops again after his return, Freddie put himself on “Battle Orders” to fly with recently promoted Flight Lieutenant Ken Ames and their crew. Aboard ND335 “L for Love” they took off at 20:01 on 10 March 1944 led by Wing Commander Bill Deas to bomb Clermont Ferrand. Attempting to reduce civilian casualties near the target in France the Lancasters bombed from below 10,000 feet and the crew reported attacking at 9,300 feet on red spot flares to see concentrated fires burning. They landed home safely at 02:41 hours.

He listed himself to fly with Ken Ames and their crew again for the attack on Stuttgart on the night of

15/16 March 1944, when they flew ND335 “L for Love” again, taking off at 19:24 from East Kirkby. On the outward trip the crew noted two ships burning at sea before they flew with the bomber stream directly across France almost to the Swiss border before turning south to Stuttgart. Gaining a visual fix on the River Neckar they attacked from 21,000 feet bombing the Pathfinder laid red and green target indicators. A Messerschmitt Bf 109 single engine night fighter closed in to attack but Paddy Parle in the rear turret of Freddie’s Lancaster opened fire first and it was last seen diving out of control and in flames. The crew landed at 03:31 hours. Two more of the squadron’s crews were missing in action.

Wing Commander Deas led the next Op, an attack on Frankfurt on the night 18/19 March. Doubtless noting that Ken Ames was assigned to fly ND335 “L for Love” Freddie put himself on “Battle Orders” to fly with their crew and they took off at 19:08 hours. Over the target area there was no cloud but considerable haze and they bombed from 20,500 feet into the target area where sticks of incendiaries were afire. In a night notable for intense night fighter activity in and around Stuttgart they were again attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 single engine night fighter and their trusty rear gunner Paddy Parle shot it down (recommended for the Distinguished Flying Medal). The crew

landed safely at base at 00:43. One of their crews “Failed To Return” and Freddie lost another of his lads, 19 year old Sergeant Winston Clough.

Several nights followed when the crew were rested, some of the squadron still flew and another four Lancasters and crews were shot down, before the terrible raid on the night 30/31 March, possibly the worst experience of the war for Bomber Command.

“Battle Orders” of 30 March 1944 listed Ken Ames, Freddie and crew to operate in Lancaster ND335 “L for Love” carrying a “sprog” pilot to gain operational experience in the massive attack on Nuremburg, a long range target which was sure to be heavily defended. They took off at 22:02 hours. Struggling against heavy winds bomber crews flying on this attack reported seeing bombers being shot down all around them during the latter part of the outward trip, more shot down around them during their time in the target area and even more as the bombers struggled back across Germany and France on their way home. 95 bombers out of the 795 which attacked Nuremburg were shot down. Freddie’s crew noted 10/10 cloud in the target area which they bombed from 19,250 feet. The crew returned safely at 06:17 hours. No. 630 Squadron lost 3 crews on that night, 21 men.

Illustrated below is a No. 630 Squadron Lancaster, bomb bays gaping wide and payload about to drop, viewed from a sister aircraft during the attack on Nuremburg.

[photograph]

During late April 1944 a No, 630 Squadron photo was taken at RAF East Kirkby.

The squadron leadership pictured in the front row (below) are left to right – Squadron Ldr Roy Calvert DFC & 2 Bars (B-Flight Commander), Wing Cdr Bill Deas DSO DFC & Bar, Squadron Ldr Edward Butler DFC & 2 Bars (A-Flight commander), Flight Lieut. “Sam” Weller DFC (Senior pilot A-Flight), Flight Lieut. Charles Martin MM (Adjutant), Flight Lieut Freddie Spencer DFC (Flight Engr Leader),

[photograph]

An enlarged section is below (below).

Beneath the Flight Engineers brevet he is wearing the ribbon of the 1939-43 (later 1939-45) Star.

[photograph]

On 5 April 1944 Ken Ames, Freddie and the crew were again listed on “Battle Orders”, they took off at the head of the squadron at 19:48 hours aboard Lancaster ME650 “B – Baker”. The target was a factory complex at Toulouse in France and Pathfinder marker flares were dropped from a Mosquito flown by Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire VC DSO DFC. Zero cloud was experienced in the target area with excellent visibility enabling accurate bombing from about 8,000 feet, the factory was a mass of flames following the attack. Many crews reported German radio counter measures being active. They landed safely at Barford St John on return at 04:11 due to mist at East Kirkby.

[photograph]

Freddie usually flew with Ken Ames (above).

The night of 9/10 April 1944 was to be No. 630 Squadron’s first operation to plant anti-submarine mines in the Baltic. The Garden assigned to the crew was known as “Tangerine” and its position was in Danzig Bay off the u-boat base. Ken Ames was designated Deputy Leader for the entire attack which was planned to utilise the H2S, Fishpond, API and Mandrel electronic devices to ensure success.

Aboard Lancaster ND335 “L for Love” the crew took off at 21:25 hours and on arrival in the target area found conditions particularly clear. Jim Wright (navigator) located the Datum Point with ease enabling a steady run and accurate placement of their mines. Throughout the run they were under heavy attack from heavy flak guns between Pilau and Palmickan and also fast firing cannons aboard ships. They returned safely and landed at 06:40 hours.

On the very next night the crew were again operational, taking off in ND335 “L for Love” at 22:20 hours on 10 April to bomb an industrial area in Tours/France. The arrived in good visibility to make a highly successful attack after pinpoint marking by Wing Commander Deas. The attack was carried out at low level to avoid French casualties and they bombed from between 5,500 and 7,500 feet.

ND335’s bomb load this night included some 6 hour delay bombs. They landed back at East Kirkby at 04:08 hours.

A week rest followed before Ken Ames, Freddie and crew were to operate again, they took ND335 “L for Love” to bomb the railway marshalling yards at Juvissy. Taking off from East Kirkby at 20:42 hours they made an uneventful outward flight, found the target area cloud free and bombed without incident. There was little anti aircraft fire and they returned to land at 01:21 hours. BBC war correspondents were waiting at East Kirkby as they landed and interviewed a number of crews.

[photograph]

[photograph]

The above photo shows a No. 630 Squadron crew being interviewed after that attack.

[photograph]

Juvissy marshalling yards before and after the attack.

[photograph]

With Ken Ames and some of the crew on leave Freddie evidently noted that as Sergeant Alex Frame, flight engineer in the highly experienced crew of Flight Lieut. JCW “Sam” Weller DFC, was unable to fly, there was a seat to be filled. He put himself on the “Battle Order” of 23 April for another night mining operation in the Baltic. With Same Weller he took off in Lancaster ME650 “B – Baker” at 21:30 that evening and headed out across the North Sea. They noted night fighters over Denmark but were not attacked themselves and arriving in a Gardening area code named “Geraniums” they parachuted mines into an area off the German port of Swinemunde. Little flak was experienced and they landed back at base at 04:10 hours.

The following night 24 April in exactly the same situation Freddie flew with Sam Weller’s crew. They took Lancaster ME650 on a long range bombing attack on Munich in Southern Germany. Taking off at 20:46 they were led by flight commander Squadron Leader Roy Calvert away from East Kirkby, one of their aircraft (flown by Pilot Officer Ron Bailey) crashed on take off after suffering engine failure. Arriving over the target area they encountered searchlights, heavy flak and night fighters.

Several of No. 630 Squadron’s aircraft were attacked but Freddie’s Lancaster was not. A highly accurate bombing attack was made and they headed for home. The Lancaster of their friend “Blue” Rackley RAAF was badly shot up by a night fighter and unable to make it home Blue flew it to Corsica where they belly landed, one crew member was dead. Meanwhile ME650 landed safely back at base at 06:35.