A Love Story by Grandad

Title

A Love Story by Grandad

Description

An account of Jim Allen's life from 1941 to 1997. He details meeting his future wife and their intermittent courtship. There is great detail about his social life and relationship with his future wife. There are two pages of photographs:

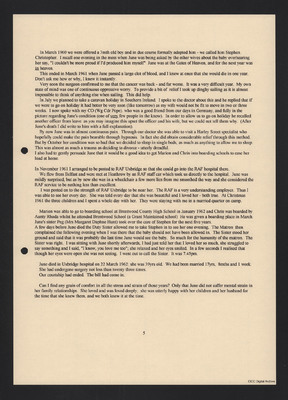

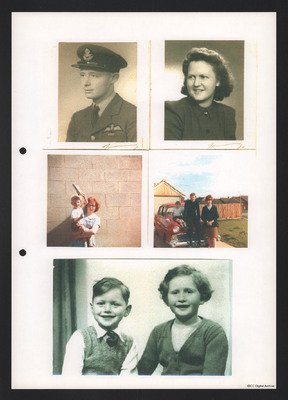

First page: Jim in uniform, June, young woman with child, three children (one a young boy) sitting on car, young boy and girl.

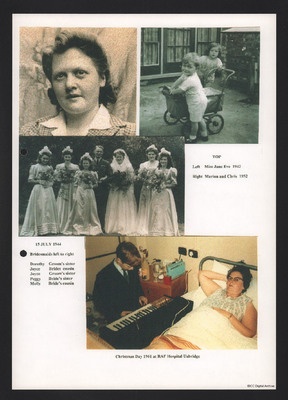

Second page: Miss June Eve 1942; Marion and Chris 1952; Wedding photograph 15 July 1944, giving names of bridesmaids (Dorothy, Joyce, Joyce, Peggy, Molly); photograph of June in hospital bed, with boy playing electric organ captioned 'Christmas Day 1961, RAF Hospital Uxbridge'.

First page: Jim in uniform, June, young woman with child, three children (one a young boy) sitting on car, young boy and girl.

Second page: Miss June Eve 1942; Marion and Chris 1952; Wedding photograph 15 July 1944, giving names of bridesmaids (Dorothy, Joyce, Joyce, Peggy, Molly); photograph of June in hospital bed, with boy playing electric organ captioned 'Christmas Day 1961, RAF Hospital Uxbridge'.

Creator

Date

1997-11

Spatial Coverage

Language

Format

Seven typewritten sheets and two pages of photographs

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

MAllenJH179996-160512-020001,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020002,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020003,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020004,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020005,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020006,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020007,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020008,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020009

MAllenJH179996-160512-020002,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020003,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020004,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020005,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020006,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020007,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020008,

MAllenJH179996-160512-020009

Transcription

To my grandchildren

With grateful thanks to Peggy and Sam Hunt

and

Irene and Peter Hinchliffe

A Love Story

by

Granddad

J H Allen

November 1997

[Page Break]

In the Spring of 1941 I was working for the Plessey Co. Ltd, Vicarage Lane Ilford Essex as an apprentice instrument maker. The office of the instrument shop was a wood and glass box about 12ft square. My lathe was about 15ft from the door of this office. One day a fellow turner said to me, “what do you think of our new office girls?” I looked up to see a young lady learning forward over a table in the office displaying some 4” of white leg between the top of her stocking and the hem of her skirt atop a very shapely pair of legs. My first view of a girl who years later would become my wife. Her name was June; I thought her rather plain with steel-rimmed spectacles.

On 23 June’41 (a Sunday) a number of us were working including out office girl. It came up that her birthday was on the 26th June; she would be 19. Someone suggested that we give her a birthday kiss, and we all did,. It was the first time I had kissed a girl. I was one month short of my 18th birthday.

Shortly afterwards I asked her if she would ‘come to the pictures with me ‘– standard request then for a date. She agreed and on the following Saturday we went to see a film at a cinema in Romford; we both lived in Romford. No romance blossomed, in fact she dated another (rather handsome) chap in the instrument shop, named Johnny Johnson. However I did learn that her surname was Eve, which somewhat intrigued me.

I joined the RAF on 30 March 1942. On my first leave some thirteen weeks later I contacted June and was gratified to find she was no longer dating JJ and there was no-one else in her sights. Leave over I departed ad we agreed to write. This rather gentle romance jogged along until November 1942 when I sailed for Canada – on the Queen Elizabeth. I had a double cabin shared with fourteen other airman tiered bunks three high. I was now in love with June, but she made it quote plain that she regarded me as no more than a friend. In fact this was the second time she had made this clear to me. Before departing I purchased a writing case for her (it cost thirty shillings, four days pay, which I still have 55 yrs on) in the hope that it would encourage her to write.

Whilst training in Canada I wrote to her and she replied. One letter I received about April ’43 informed me that she was much interested in another young man, and it was clear that I was well down the list in her affections. This was the third occasion on which she has in effect told me to go away, [sic] Even so I maintained contact as I expected to return by early July’43. In fact I had seriously debated with myself whilst in hospital in May ’43 suffering from a very high temperature whether or not I really wanted to marry her. I concluded that I most definitely did want her, but felt that she would probably not return my feelings – my hard luck! It is worth recording that in all my training I really did strive to so well as I felt very strongly that if I failed to get my wings I would not return to Romford, being unable to face her as a failure, Thus she was an inspiration to me – that is no exaggeration.

On return to Romford in July’43 I called on June (without much hope) to learn she had no other attachment. I had two weeks leave during which time we visited the cinema and theatre and spent as much time as possible ‘walking out’ together. June was able to take one week summer holiday so we were able to spend quite a bit of time together [sic] On one such occasion she said “Look, there’s a church, lets go in and get married!. Being totally taken aback I made some stupid remark about it being a good idea as it would reduce my income tax. It did however cause me much thought that evening – this being the first intimation that there might just be a glimmer of hope for me, The following day I told her again that I loved her and asked frankly “Is there any chance for me?” When she replied “There’s a great chance” I was simply over the moon. We agreed to marry ‘when the war is over’ and announced the engagement to our families. The date was 16th July 1943. June was 21 yrs, I was a fortnight short of my 20th birthday.

We were now in a sort of limbo; unable to set a date to marry and restrained by our upbringing and culture from enjoying each other before marriage. A majority of young women at the time strove to preserve virginity till their wedding night. June was such a girl and indeed I expected it of her. We were waiting for the war to end.

On January 21 ’44 I was flying a Wellington on a night cross-country exercise and crashed just outside York bear a village called Askam Bryan. It was pitch black and we hit the ground at over 100mph, downwind some five seconds after I saw it in the landing light [sic] All six of us got out of the aircraft without a scratch. The plane was reduced to scrap and one engine was on fire about thirty yards from the aircraft.

This incident triggered the date of our wedding as June said “Let’s get married and take what happiness we can while we can”. We set the date for July – in fact we married on St Swithin’s day. 15 July. In January ’44 the war was far from over, and I would be on an operational bomber squadron in a few months.

My leave started on Thursday 31 July, we married on the Saturday in Romford with ‘doodle-bugs’ (V-1 flying bombs) passing over head – speeches bring curtailed until they had passed - then departed to spend our wedding night at the Winston hotel in Jermyn St. London, further to the sound of flying bombs passing by accompanied by the crash of anti –

1

[Page break]

aircraft fire. We then had three days honeymoon at Marlow (Bucks) and on the Wednesday night I travelled back to camp to arrive for breakfast on the Thursday, to learn that during the night the squadron had lost six aircraft, two crews from my flight. On 23 July I carried out my first operation as a married man, to Kiel where U-boats were being built. My very new wife was now in line to become a very new widow.

As you know, by our wedding day I had flown twenty-twenty two operations and flew a further eighteen after it. You can read two or three of them in the book, “Based at Burn”. June was sometimes asked how she felt knowing that I was operating. She said she felt no great anxiety as I always seemed so confident that my crew would services. This despite having met us (the crew) twice at Liverpool St station, London as we returned to base by rail after landing away due to the damage to our aircraft. How I felt in surviving the tour in Bomber Command and later flying the Atlantic in winter in York aircraft is another story which has no place here apart from the fact that June was always my home port and reason for returning.

In 1946 we bought a house for £900 with a mortgage of £640. It was a poor house in a non-salubrious area and the top half of the house was let to a family with two small children at a ‘controlled’ i.e. low rent, and the law gave them total protection against loss of their accommodation. I was still in the RAF so this really was no problem; we had our own home small as it was.

Shortly after the war in Europe ended (May 1945) June developed a strong urge to have a baby. There is no greater force in human emotions than this; it is inconceivable to anyone who has not come up against it.

Cutting short a two-year-long difficult story in April 1947 after numerous painful and embarrassing visits to the hospital for both of us, and the last of which for June consisted of oil being forced into her reproductive tract (under anaesthetic during which she woke up) in order that is could be x-rayed the verdict was delivered: “In the present state of medical knowledge we have to say that we think it is not possible for you to conceive. The fallopian tubes are so malformed that it is impossible, and we cannot correct it with surgery. This is a congenital condition that you were born with. You may prove us wrong one day – it has been know – but we think not.

The verdict produced a profound depression. We enquired about adoption, to be told that we could not be considered until we were both over the age of 25yrs of age. (in April ’47 I was under 24yrs and June not yet 25yrs) It is quite impossible to find words to describe the depths of misery that these to blows produced. At the time I was stationed reasonably near June and got home most weekends.

I came home for the weekend in late July ’47 to be greeted by my wife in a state of supreme suppressed excitement. She was simply bursting with the news that her period was [underlined] two days [/underlined] late. She was pregnant and no amount of cautionary words would alter it. She KNEW it and she would have a daughter who would be called ‘Marion’!! She couldn’t wait for the first bout of morning sickness. When her condition was confirmed a week or so later her joy was boundless. From the depths of despair to overwhelming elation in three months.!!

I left the RAF in October ’47 having served a year beyond my demob date. I would have liked to continue, but pressure to leave was now great; our living conditions were not good and I felt I needed to be with June when the baby arrived.

I returned to engineering, working for a small firm in Brentwood, Essex. My pay was two shillings an hour, fifty hours per week. After working inside for a few weeks I simply could not stand it any longer and became a bus conductor with London Transport, the pay was just under six pounds per week and I would be working outside. I was in fact the best job I could get.

Our daughter Marion was born ten days late on 29 March 1948, weighing-in at 10lbs. As the midwife said, No wonder it was a tough job”. The baby was born at home as it was not possible to get into a maternity ward unless complications were expected. Our accommodation comprised of two rooms and a small kitchen. The only heating being a small fireplace in each room – central heating was simply not on and coal was rationed. The after-birth was wrapped in newspaper and put on the small fire in the room where our daughter was born. The attendance of the doctor cost £7, the midwife £3.

June’s Aunt Rhoda came in each day to help with the baby until June was able to get up again.

Up to a point the job of bus conductor was quite enjoyable, it also had some prospect of advancement and after a year I did apply for the a post as Inspector. I didn’t get it as it was policy not to promote a conductor until he had several years experience – primarily to make him acceptable to other drivers and conductors. This attitude and the lowly status of the job produced a high degree of frustration. June never wavered in her support for me: from being the wife of an officer in the RAF she was now the wife of a bus conductor. By this time our living conditions became intolerable due to the attitude of the family upstairs. As always their darling little children were just playing; to us it was continual intolerable noise without relief.

When Marion was three months old we were able to buy a house at Ardleigh Green, Hornchurch. We took out a mortgage for £1300, cost £2 per week plus 10 shillings per week rates. May take home pay was £5 per week. We were

[Page Break]

Utterly desperate to get a place of our own, Ardleigh Green was a much better area and we felt pleased to have moved and improved our situation. In the event we had to let two rooms to a newly married couple to help pay the mortgage, but overall we were better off.

In June 1949 my wife asked how I felt about a second child. I replied that this was entirely a matter of her choice; she would have to produce the child and do 99% of the upbringing for a least the first three years. June said that she had always wanted two children: Marion was now 14mths old she would prefer to bring up two children together rather than several years apart. In contrast to the difficulties of conceiving out daughter June became pregnant immediately (I now think that both our children were conceived on 26 June – her birthday). As certain as she had been that the first-born would be a daughter June was now equally certain that she would bear a son. She duly did on 14 March 1950, on schedule. Chris was born on Oldchurch hospital, Romford, as this situation was now improved.

I visited mother and son that evening; looking down on Chris I said to him, “What have we done. We created you quite deliberately, you are much wanted yet what future have you? Before you reach school age you are likely to be a little heap of atomic ash”. At the time it did look as if we would be at war with Russia quite soon; the whole atmosphere was depressing. All the newspaper talk was of Foreign Ministers meeting for a ‘last chance’ to avert war. A week later Marion met her new brother and our family was complete.

Chris was born with a band of eczema across his chest. He suffered severely and continuously with this complaint for over fourteen years; it never did clear up. The doctors assured us from birth that ‘it would clear up in a couple of years’ always two years ahead! He suffered severely from the itching of this complaint; the amazing thing to us was that he was always very lively and so cheerful accepted his bandaged arms and legs. The strange thing was that neither of our families had a history of eczema.

June was now totally happy with the family she wanted and excelling in what was really her destiny – to be a wife and mother. Financially we were not well off, in fact living literally from one pay day to the next. In 1950 food prices were relatively twice the prices of the 1990s. With each other we were totally happy. It is fashionable now to sneer at such statement on the grounds that the wife must thereby be a doormat: this is total rubbish. My mother burned herself to death due to the treatment she received from her husband; my wife was never less than my equal and we were both happy with our condition.

In June 1950 I started work with the Prudential Assurance Co. Ltd as an insurance agent. It was quite an interesting job and I got to a point where I enjoyed calling on families. Some families opened my eyes more than somewhat. I found myself invited in for a cup of tea many times, not so much for refreshment as for someone for the wife to talk to. If the stories I heard were half true some wives lived appalling lives at the hands of their husbands. It was almost impossible in those days for the wife to escape from home (especially if she had children) other than ‘going back to mother’ – regarded as shameful; she got precious sympathy. In some cases a wife would pay pennies per week insurance on her husband’s life and beg me to keep it secret as the husband would beat her up if he knew. The same husband considered talking out life insurance as the equivalent to signing his death warrant. Half a century on I look back and consider that these wives were not exaggerating.

There was as much marital disharmony then as today and I was appalled to find that of the families I called on, as ‘The Man from the Prudential’, that only one or two of them lived in genuine harmony.

In July 1951 a cousin of June’s Joyce Levi, called on us one afternoon. She was in the WRNS (Womens Royal Naval Service) and just before she departed I said to her, “I often wish I was still in the Service”. When she had gone June said to me, “If you really feel that you’d like to go back in the RAF don’t let me stop you”. After some little discussion to be sure that this truly was the case I wrote that evening to the Air Ministry to ask if there was any possibility of me rejoining the RAF. The short answer was, “Come up and see us and let’s talk”. I was asked if I would like to be a flying instructor. Would a duck like to swim? Unfortunately, as I expected, my eyesight was just not up to standard. However all was not lost.

On 19 October 1951 I returned to the Royal Air Force. The Korean War provided the opportunity to rejoin and I considered myself extremely fortunate to return with a commission (rank of Flying Officer) in the Fighter Control Branch. My flying experience was the crucial factor. June was not keen for me to RAF, but accepted that I was not happy in civil life, and the RAFF would pay me £53 per month – nearly double our current income. In the event June took happily to service life and agreed that it was the correct decision. Once again she was totally supportive.

1953 was a year I remember for two particular reasons. Our ninth wedding anniversary instead of giving June a card I wrote her a short letter saying quite simply that she was my reason for living. Many years later I gave this letter to our daughter Marion that her children might know that in a world of much martial distress it is possible for two lovers to remain so down the years. Little did we know that we were then half way through our life together. At about this

3

[Page Break]

time I asked June if she could tell me at what point she decided to accept me after telling me three times to go away. She replied that there was no particular moment, a sort of growing realisation ‘that you were always there’ which developed into the feeling that this was a desirable state that she wished to maintain on a permanent basis.

We were stationed at Acklington, Northumberland. This is a very beautiful county and it was a happy time for us, June spent some time in the hospital in Newcastle as in 1955 she underwent hysterectomy (removal of the womb) which meant a round journey of some 80 miles to visit her. I was able to fit this in with talks I gave to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force in the evening so reducing travelling expenses. June seemed to be in and out of hospitals on a continuous basis from about 1946. She once said to me “In trying to have a baby it was a case of ‘Take your knickers off’ and since the birth of the babies it’s been the same story.”

In December of the same year I was granted a permanent commission in the RAF. It was a ‘Branch Commission’ which meant that I wold not be promoted above the rank of Flight Lieutenant, but we were both delighted as it meant we would now be able to spend many years in the RAF. It wasn’t a job; it was a way of life and we liked it.

We spent two and a half years in Germany, July ’56 to February ‘59, which was a joy to us all. Life was good to us. On our thirteenth wedding anniversary in 1957 June wrote on her card to me, “ You could have not made me happier in the 13 yrs of our marriage”. We were indeed a happy family During [sic] our time there we were able to travel and see the country, and also to visit Austria. Today this nothing exceptional, but in 1950s it was still an adventure to see another country. And of course to try the food and wines! I had said to June many times, “If I had a thousand years with you, when it was time to go I’d want another five minutes”. Several times down the years I had voiced to her a fear that as we seemed to be so much happier than many families in the world, and indeed some we knew, that one day a bill would come in to pay for it. She always replied, “Let’s enjoy the life we have and be glad of it and not worry unduly”.

In 1958 June had to spend a few weeks in hospital in Germany The [sic] Services has a military hospital there exceedingly well equipped and run.

We moved to Ireland in February 1959. Marion was now 11 yrs, Chris 9 yrs. We discussed adopting two children as June could have no more. In five years our children would be thinking of leaving home one way or another we felt that we had years ahead of us to take on two children, say two years apart. And there were many children in the world who were not wanted. At that time abortion was a criminal offence and to be an unmarried mother was a matter of great shame, both to the girl and her family. In July ’59 we were placed on the register as prospective adoptees, in Belfast. June was now bubbling with joy at the prospect of another baby.

In August ‘59 June went into hospital with suspected ovarian cyst. I was told one day that she would undergo surgery that afternoon at 2pm. I arrived at the hospital at six o’clock ad went straight to the ward (I knew the way!). On entering the ward I saw her bed by the door [underlined] stripped down to the mattress [/underlined]: my soul screamed. The Sister now spoke saying that she has intended to stop me entering as my wife returned. She had been seven hours in the operating theatre. The surgeons told me that they had found stomach cancer and has removed over 4ft of her intestine. They also gave me the usual rubbish about having cleared it all out, with a good chance of it not recurring. She was in hospital for ten continuous weeks.

It must be mentioned here that June’s grandmother had died of throat cancer (the last two weeks being nothing short of slow strangulation as doctors then, as now, were not allowed to provide death with dignity) and her mother’s sister also died of cancer at age 37 years. As a result June has a profound fear of cancer. When the surgeon told me that he has found I faced a major dilemma. As she had so much agony of body I could not give her agony of mind by telling her of the cancer; it might not develop anyway. I could not cancel plans for adoption without giving reason – which would have to be the truth as she would pick up a lie at once, which would simply compound the problems. And what would out relationship be of the plans were cancelled and the cancer [underline] was [/underlined] cleared? There seemed to be no alternative but to proceed as planned and hope for the best.

[Page Break]

In March 1960 we were offered a 3 mth old boy and in due course formally adopted him – we called him Stephen Christopher. I recall one evening in the mess when June was being asked by the other wives about the baby overhearing her say, “I couldn’t be more proud if I’d produced him myself” June was at the Gates of Heaven, and for the next year was [underlined] in [/underlined] heaven.

This ended in March 1961 when June passed a large clot of blood, and I knew at once that she would die in one year. Don’t ask me how or why, I knew instantly.

Very soon the surgeon confirmed that the cancer was back – and far worse. It was a difficult year. My own state of mind was one of continuous oppressive worry. To provide a bit of relief I took up dinghy sailing as it is almost impossible to think of anything else when sailing. This did help.

In July we planned to take a caravan holiday in Southern Ireland. I spoke to the doctor about this and he replied that s we were to go on holiday it has better be very soon (like tomorrow) as my wife would not be fit to move in two or three weeks. I now spoke with my CO (Wg Cdr Pope). who [sic] was a good friend from our days in Germany, and fully in the picture regarding June’s condition (one of [underlined] very [/underlined] few people in the know). In order to allow us to go on holiday he recalled another officer from leave; as you may imagine this upset the officer and his wife, but we could not tell them why. (After June’s death did write to him with a full explanation).

By now June was in almost continuous pain. Through our doctor she was able to visit a Harley Street specialist who hopefully could make the pain bearable through hypnosis. In fact she did obtain considerable relief through this method. But by October her condition was so bad that we decided to sleep in single beds, as much as anything to allow me to sleep. This was almost as much trauma s deciding to divorce – utterly dreadful.

I also had to gently persuade June that it would be a good idea to get Marion and Chris into boarding school to ease her load at home.

In November 1961 I arranged to be posted to RAF Uxbridge so that she could go into the RAF hospital there.

We flew from Belfast and were met a Heathrow by and RAF staff car which took us directly to the hospital. June was mildly surprised, but by now she was in a wheelchair a few more lies from me smoothed the way and considered the RAF service to be nothing less than excellent.

I was posted on to the strength of RAF Uxbridge to be near her. The RAF is a very understanding employer. Thus I was able to see her every day. She was told every day that she was beautiful and I loved her – both true. At Christmas 1961 the three children and I spent the whole day with her. They were staying with me in a married quarter on camp.

Marion was able to go to boarding school at Brentwood County High School in January 1962 and Chris was boarded by Aunty Rhoda whilst he attended Brentwood School (a Grant Maintained school) He was given a boarding place in March. June’s sister Peg (Mrs Margret Daphne Hunt) took over care of Stephen for the next five years.

A few days before June died the Duty Sister allowed me to take Stephen in to see her one evening. The Matron then complained the following evening when I was there that the baby should not have been allowed in. The Sister stood her ground and said that is was probably the last time June would see the baby. So much for the humanity of the matron. The Sister was right. I was sitting with June shortly afterwards, I has just told her I loved her so much, he struggled to say something and I said, I know, you love me too!; she relaxed and her eyes smiles. In a few seconds I realised that though her eyes were open she was not seeing. I went out to call the Sister. It was 7.45pm.

June died in Uxbridge hospital on 22 March 1962: She was 39 yrs old. We had been married 17yrs, 8 mths and 1 week. She has undergone surgery not less than twenty three times.

Our courtship had ended. The bill had come in.

Can I find a grain of comfort in all the stress and strain of those years. Only that June did not suffer mental strain in her family relationships. She loved and was loved deeply; she was utterly happy with her children and her husband for the time that she knew them, and we both knew it at the time.

5

[Page Break]

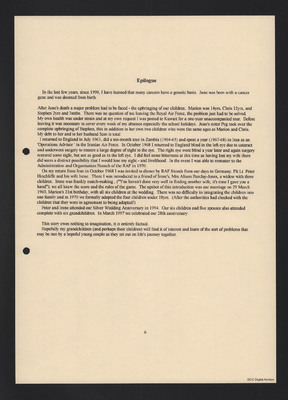

Epilogue

In the last few years, since 1990 I have learned that many cancers have a genetic basis. June was born with a cancer gene and was doomed from birth.

After June’s death a major problem has to be faced – the upbringing of our children. Marion was 14yrs, Chris 12 yrs, and Stephen 2yrs and 3 mnths. There was no question of me leaving the Royal Air Force, the problem just has to be solved. My own health was under strain and at my own request I was posted to Kuwait for a one-year unaccompanied tour. Before leaving it was necessary to cover every week of my absence especially the school holidays. June’s sister Peg took over the complete upbringing of Stephen this in addition to her own children who were the same age as Marion and Chris. My debt to her and to her husband Sam is total.

I returned to England in July 1963, did a ten-month tour in Zambia (1964-65) and spent a year (1967-68) in Iran as an ‘Operations Advisor’ in the Iranian Air Force. In October 1968 I returned to England blind in the left eye due to cataract and underwent surgery to restore a large degree of sight to the eye. The right eye went blind a year later and again surgery restored some sight, but not as good as the left eye. I did feel some bitterness as this time as having lost my wife there did seem some distinct possibility that I would lose my sight – and livelihood. In the event I was able to remuster to the Administration and Organisation Branch of the RAF in 1970.

On my return from Iran in October 1968 I was invited to dinner by RAF friends from out days in Germany. Flt Lt Peter Hinchliffe and his wife Irene. There I was introduced to Irene’s friend Mrs Alison Barclay- Jones, a widow with three children. Irene was frankly match-making, (“You haven’t done very well in finding another wife; it’s time I gave you a hand”); we all knew the score and the rules of the game. The upshot of this introduction was out marriage on 29 March 1969, Marion’s 21st birthday, with all six children at the wedding. There was no difficulty in integrating the children into one family and in 1970 we formally adopted the four children under 18 yrs. (After the authorities had checked with the children that they were in agreement to being adopted!)

Peter and Irene attended our Silver Wedding Anniversary in 1994. Our six children and five spouses attended complete with six grandchildren. In Match 1997 we celebrated our 28th anniversary.

The story owes nothing to imagination, it is entirely factual.

Hopefully my grandchildren (and perhaps their children) will find it of interest and learn of the sort of problems that may be met by a hopeful young couple as they set out on life’s journey together.

6

[Page Break]

Photographs

[Page Break]

Top

Left Miss June Eve 1942

Right Marion and Chris 1952

15 July 1944

Bridesmaids left to right

Dorothy Groom’s sister

Joyce Brides Cousin

Joyce Groom’s sister

Peggy Bride’s sister

Molly Brides’s cousin

Christmas Day 1961 at RAF Hospital Uxbridge

With grateful thanks to Peggy and Sam Hunt

and

Irene and Peter Hinchliffe

A Love Story

by

Granddad

J H Allen

November 1997

[Page Break]

In the Spring of 1941 I was working for the Plessey Co. Ltd, Vicarage Lane Ilford Essex as an apprentice instrument maker. The office of the instrument shop was a wood and glass box about 12ft square. My lathe was about 15ft from the door of this office. One day a fellow turner said to me, “what do you think of our new office girls?” I looked up to see a young lady learning forward over a table in the office displaying some 4” of white leg between the top of her stocking and the hem of her skirt atop a very shapely pair of legs. My first view of a girl who years later would become my wife. Her name was June; I thought her rather plain with steel-rimmed spectacles.

On 23 June’41 (a Sunday) a number of us were working including out office girl. It came up that her birthday was on the 26th June; she would be 19. Someone suggested that we give her a birthday kiss, and we all did,. It was the first time I had kissed a girl. I was one month short of my 18th birthday.

Shortly afterwards I asked her if she would ‘come to the pictures with me ‘– standard request then for a date. She agreed and on the following Saturday we went to see a film at a cinema in Romford; we both lived in Romford. No romance blossomed, in fact she dated another (rather handsome) chap in the instrument shop, named Johnny Johnson. However I did learn that her surname was Eve, which somewhat intrigued me.

I joined the RAF on 30 March 1942. On my first leave some thirteen weeks later I contacted June and was gratified to find she was no longer dating JJ and there was no-one else in her sights. Leave over I departed ad we agreed to write. This rather gentle romance jogged along until November 1942 when I sailed for Canada – on the Queen Elizabeth. I had a double cabin shared with fourteen other airman tiered bunks three high. I was now in love with June, but she made it quote plain that she regarded me as no more than a friend. In fact this was the second time she had made this clear to me. Before departing I purchased a writing case for her (it cost thirty shillings, four days pay, which I still have 55 yrs on) in the hope that it would encourage her to write.

Whilst training in Canada I wrote to her and she replied. One letter I received about April ’43 informed me that she was much interested in another young man, and it was clear that I was well down the list in her affections. This was the third occasion on which she has in effect told me to go away, [sic] Even so I maintained contact as I expected to return by early July’43. In fact I had seriously debated with myself whilst in hospital in May ’43 suffering from a very high temperature whether or not I really wanted to marry her. I concluded that I most definitely did want her, but felt that she would probably not return my feelings – my hard luck! It is worth recording that in all my training I really did strive to so well as I felt very strongly that if I failed to get my wings I would not return to Romford, being unable to face her as a failure, Thus she was an inspiration to me – that is no exaggeration.

On return to Romford in July’43 I called on June (without much hope) to learn she had no other attachment. I had two weeks leave during which time we visited the cinema and theatre and spent as much time as possible ‘walking out’ together. June was able to take one week summer holiday so we were able to spend quite a bit of time together [sic] On one such occasion she said “Look, there’s a church, lets go in and get married!. Being totally taken aback I made some stupid remark about it being a good idea as it would reduce my income tax. It did however cause me much thought that evening – this being the first intimation that there might just be a glimmer of hope for me, The following day I told her again that I loved her and asked frankly “Is there any chance for me?” When she replied “There’s a great chance” I was simply over the moon. We agreed to marry ‘when the war is over’ and announced the engagement to our families. The date was 16th July 1943. June was 21 yrs, I was a fortnight short of my 20th birthday.

We were now in a sort of limbo; unable to set a date to marry and restrained by our upbringing and culture from enjoying each other before marriage. A majority of young women at the time strove to preserve virginity till their wedding night. June was such a girl and indeed I expected it of her. We were waiting for the war to end.

On January 21 ’44 I was flying a Wellington on a night cross-country exercise and crashed just outside York bear a village called Askam Bryan. It was pitch black and we hit the ground at over 100mph, downwind some five seconds after I saw it in the landing light [sic] All six of us got out of the aircraft without a scratch. The plane was reduced to scrap and one engine was on fire about thirty yards from the aircraft.

This incident triggered the date of our wedding as June said “Let’s get married and take what happiness we can while we can”. We set the date for July – in fact we married on St Swithin’s day. 15 July. In January ’44 the war was far from over, and I would be on an operational bomber squadron in a few months.

My leave started on Thursday 31 July, we married on the Saturday in Romford with ‘doodle-bugs’ (V-1 flying bombs) passing over head – speeches bring curtailed until they had passed - then departed to spend our wedding night at the Winston hotel in Jermyn St. London, further to the sound of flying bombs passing by accompanied by the crash of anti –

1

[Page break]

aircraft fire. We then had three days honeymoon at Marlow (Bucks) and on the Wednesday night I travelled back to camp to arrive for breakfast on the Thursday, to learn that during the night the squadron had lost six aircraft, two crews from my flight. On 23 July I carried out my first operation as a married man, to Kiel where U-boats were being built. My very new wife was now in line to become a very new widow.

As you know, by our wedding day I had flown twenty-twenty two operations and flew a further eighteen after it. You can read two or three of them in the book, “Based at Burn”. June was sometimes asked how she felt knowing that I was operating. She said she felt no great anxiety as I always seemed so confident that my crew would services. This despite having met us (the crew) twice at Liverpool St station, London as we returned to base by rail after landing away due to the damage to our aircraft. How I felt in surviving the tour in Bomber Command and later flying the Atlantic in winter in York aircraft is another story which has no place here apart from the fact that June was always my home port and reason for returning.

In 1946 we bought a house for £900 with a mortgage of £640. It was a poor house in a non-salubrious area and the top half of the house was let to a family with two small children at a ‘controlled’ i.e. low rent, and the law gave them total protection against loss of their accommodation. I was still in the RAF so this really was no problem; we had our own home small as it was.

Shortly after the war in Europe ended (May 1945) June developed a strong urge to have a baby. There is no greater force in human emotions than this; it is inconceivable to anyone who has not come up against it.

Cutting short a two-year-long difficult story in April 1947 after numerous painful and embarrassing visits to the hospital for both of us, and the last of which for June consisted of oil being forced into her reproductive tract (under anaesthetic during which she woke up) in order that is could be x-rayed the verdict was delivered: “In the present state of medical knowledge we have to say that we think it is not possible for you to conceive. The fallopian tubes are so malformed that it is impossible, and we cannot correct it with surgery. This is a congenital condition that you were born with. You may prove us wrong one day – it has been know – but we think not.

The verdict produced a profound depression. We enquired about adoption, to be told that we could not be considered until we were both over the age of 25yrs of age. (in April ’47 I was under 24yrs and June not yet 25yrs) It is quite impossible to find words to describe the depths of misery that these to blows produced. At the time I was stationed reasonably near June and got home most weekends.

I came home for the weekend in late July ’47 to be greeted by my wife in a state of supreme suppressed excitement. She was simply bursting with the news that her period was [underlined] two days [/underlined] late. She was pregnant and no amount of cautionary words would alter it. She KNEW it and she would have a daughter who would be called ‘Marion’!! She couldn’t wait for the first bout of morning sickness. When her condition was confirmed a week or so later her joy was boundless. From the depths of despair to overwhelming elation in three months.!!

I left the RAF in October ’47 having served a year beyond my demob date. I would have liked to continue, but pressure to leave was now great; our living conditions were not good and I felt I needed to be with June when the baby arrived.

I returned to engineering, working for a small firm in Brentwood, Essex. My pay was two shillings an hour, fifty hours per week. After working inside for a few weeks I simply could not stand it any longer and became a bus conductor with London Transport, the pay was just under six pounds per week and I would be working outside. I was in fact the best job I could get.

Our daughter Marion was born ten days late on 29 March 1948, weighing-in at 10lbs. As the midwife said, No wonder it was a tough job”. The baby was born at home as it was not possible to get into a maternity ward unless complications were expected. Our accommodation comprised of two rooms and a small kitchen. The only heating being a small fireplace in each room – central heating was simply not on and coal was rationed. The after-birth was wrapped in newspaper and put on the small fire in the room where our daughter was born. The attendance of the doctor cost £7, the midwife £3.

June’s Aunt Rhoda came in each day to help with the baby until June was able to get up again.

Up to a point the job of bus conductor was quite enjoyable, it also had some prospect of advancement and after a year I did apply for the a post as Inspector. I didn’t get it as it was policy not to promote a conductor until he had several years experience – primarily to make him acceptable to other drivers and conductors. This attitude and the lowly status of the job produced a high degree of frustration. June never wavered in her support for me: from being the wife of an officer in the RAF she was now the wife of a bus conductor. By this time our living conditions became intolerable due to the attitude of the family upstairs. As always their darling little children were just playing; to us it was continual intolerable noise without relief.

When Marion was three months old we were able to buy a house at Ardleigh Green, Hornchurch. We took out a mortgage for £1300, cost £2 per week plus 10 shillings per week rates. May take home pay was £5 per week. We were

[Page Break]

Utterly desperate to get a place of our own, Ardleigh Green was a much better area and we felt pleased to have moved and improved our situation. In the event we had to let two rooms to a newly married couple to help pay the mortgage, but overall we were better off.

In June 1949 my wife asked how I felt about a second child. I replied that this was entirely a matter of her choice; she would have to produce the child and do 99% of the upbringing for a least the first three years. June said that she had always wanted two children: Marion was now 14mths old she would prefer to bring up two children together rather than several years apart. In contrast to the difficulties of conceiving out daughter June became pregnant immediately (I now think that both our children were conceived on 26 June – her birthday). As certain as she had been that the first-born would be a daughter June was now equally certain that she would bear a son. She duly did on 14 March 1950, on schedule. Chris was born on Oldchurch hospital, Romford, as this situation was now improved.

I visited mother and son that evening; looking down on Chris I said to him, “What have we done. We created you quite deliberately, you are much wanted yet what future have you? Before you reach school age you are likely to be a little heap of atomic ash”. At the time it did look as if we would be at war with Russia quite soon; the whole atmosphere was depressing. All the newspaper talk was of Foreign Ministers meeting for a ‘last chance’ to avert war. A week later Marion met her new brother and our family was complete.

Chris was born with a band of eczema across his chest. He suffered severely and continuously with this complaint for over fourteen years; it never did clear up. The doctors assured us from birth that ‘it would clear up in a couple of years’ always two years ahead! He suffered severely from the itching of this complaint; the amazing thing to us was that he was always very lively and so cheerful accepted his bandaged arms and legs. The strange thing was that neither of our families had a history of eczema.

June was now totally happy with the family she wanted and excelling in what was really her destiny – to be a wife and mother. Financially we were not well off, in fact living literally from one pay day to the next. In 1950 food prices were relatively twice the prices of the 1990s. With each other we were totally happy. It is fashionable now to sneer at such statement on the grounds that the wife must thereby be a doormat: this is total rubbish. My mother burned herself to death due to the treatment she received from her husband; my wife was never less than my equal and we were both happy with our condition.

In June 1950 I started work with the Prudential Assurance Co. Ltd as an insurance agent. It was quite an interesting job and I got to a point where I enjoyed calling on families. Some families opened my eyes more than somewhat. I found myself invited in for a cup of tea many times, not so much for refreshment as for someone for the wife to talk to. If the stories I heard were half true some wives lived appalling lives at the hands of their husbands. It was almost impossible in those days for the wife to escape from home (especially if she had children) other than ‘going back to mother’ – regarded as shameful; she got precious sympathy. In some cases a wife would pay pennies per week insurance on her husband’s life and beg me to keep it secret as the husband would beat her up if he knew. The same husband considered talking out life insurance as the equivalent to signing his death warrant. Half a century on I look back and consider that these wives were not exaggerating.

There was as much marital disharmony then as today and I was appalled to find that of the families I called on, as ‘The Man from the Prudential’, that only one or two of them lived in genuine harmony.

In July 1951 a cousin of June’s Joyce Levi, called on us one afternoon. She was in the WRNS (Womens Royal Naval Service) and just before she departed I said to her, “I often wish I was still in the Service”. When she had gone June said to me, “If you really feel that you’d like to go back in the RAF don’t let me stop you”. After some little discussion to be sure that this truly was the case I wrote that evening to the Air Ministry to ask if there was any possibility of me rejoining the RAF. The short answer was, “Come up and see us and let’s talk”. I was asked if I would like to be a flying instructor. Would a duck like to swim? Unfortunately, as I expected, my eyesight was just not up to standard. However all was not lost.

On 19 October 1951 I returned to the Royal Air Force. The Korean War provided the opportunity to rejoin and I considered myself extremely fortunate to return with a commission (rank of Flying Officer) in the Fighter Control Branch. My flying experience was the crucial factor. June was not keen for me to RAF, but accepted that I was not happy in civil life, and the RAFF would pay me £53 per month – nearly double our current income. In the event June took happily to service life and agreed that it was the correct decision. Once again she was totally supportive.

1953 was a year I remember for two particular reasons. Our ninth wedding anniversary instead of giving June a card I wrote her a short letter saying quite simply that she was my reason for living. Many years later I gave this letter to our daughter Marion that her children might know that in a world of much martial distress it is possible for two lovers to remain so down the years. Little did we know that we were then half way through our life together. At about this

3

[Page Break]

time I asked June if she could tell me at what point she decided to accept me after telling me three times to go away. She replied that there was no particular moment, a sort of growing realisation ‘that you were always there’ which developed into the feeling that this was a desirable state that she wished to maintain on a permanent basis.

We were stationed at Acklington, Northumberland. This is a very beautiful county and it was a happy time for us, June spent some time in the hospital in Newcastle as in 1955 she underwent hysterectomy (removal of the womb) which meant a round journey of some 80 miles to visit her. I was able to fit this in with talks I gave to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force in the evening so reducing travelling expenses. June seemed to be in and out of hospitals on a continuous basis from about 1946. She once said to me “In trying to have a baby it was a case of ‘Take your knickers off’ and since the birth of the babies it’s been the same story.”

In December of the same year I was granted a permanent commission in the RAF. It was a ‘Branch Commission’ which meant that I wold not be promoted above the rank of Flight Lieutenant, but we were both delighted as it meant we would now be able to spend many years in the RAF. It wasn’t a job; it was a way of life and we liked it.

We spent two and a half years in Germany, July ’56 to February ‘59, which was a joy to us all. Life was good to us. On our thirteenth wedding anniversary in 1957 June wrote on her card to me, “ You could have not made me happier in the 13 yrs of our marriage”. We were indeed a happy family During [sic] our time there we were able to travel and see the country, and also to visit Austria. Today this nothing exceptional, but in 1950s it was still an adventure to see another country. And of course to try the food and wines! I had said to June many times, “If I had a thousand years with you, when it was time to go I’d want another five minutes”. Several times down the years I had voiced to her a fear that as we seemed to be so much happier than many families in the world, and indeed some we knew, that one day a bill would come in to pay for it. She always replied, “Let’s enjoy the life we have and be glad of it and not worry unduly”.

In 1958 June had to spend a few weeks in hospital in Germany The [sic] Services has a military hospital there exceedingly well equipped and run.

We moved to Ireland in February 1959. Marion was now 11 yrs, Chris 9 yrs. We discussed adopting two children as June could have no more. In five years our children would be thinking of leaving home one way or another we felt that we had years ahead of us to take on two children, say two years apart. And there were many children in the world who were not wanted. At that time abortion was a criminal offence and to be an unmarried mother was a matter of great shame, both to the girl and her family. In July ’59 we were placed on the register as prospective adoptees, in Belfast. June was now bubbling with joy at the prospect of another baby.

In August ‘59 June went into hospital with suspected ovarian cyst. I was told one day that she would undergo surgery that afternoon at 2pm. I arrived at the hospital at six o’clock ad went straight to the ward (I knew the way!). On entering the ward I saw her bed by the door [underlined] stripped down to the mattress [/underlined]: my soul screamed. The Sister now spoke saying that she has intended to stop me entering as my wife returned. She had been seven hours in the operating theatre. The surgeons told me that they had found stomach cancer and has removed over 4ft of her intestine. They also gave me the usual rubbish about having cleared it all out, with a good chance of it not recurring. She was in hospital for ten continuous weeks.

It must be mentioned here that June’s grandmother had died of throat cancer (the last two weeks being nothing short of slow strangulation as doctors then, as now, were not allowed to provide death with dignity) and her mother’s sister also died of cancer at age 37 years. As a result June has a profound fear of cancer. When the surgeon told me that he has found I faced a major dilemma. As she had so much agony of body I could not give her agony of mind by telling her of the cancer; it might not develop anyway. I could not cancel plans for adoption without giving reason – which would have to be the truth as she would pick up a lie at once, which would simply compound the problems. And what would out relationship be of the plans were cancelled and the cancer [underline] was [/underlined] cleared? There seemed to be no alternative but to proceed as planned and hope for the best.

[Page Break]

In March 1960 we were offered a 3 mth old boy and in due course formally adopted him – we called him Stephen Christopher. I recall one evening in the mess when June was being asked by the other wives about the baby overhearing her say, “I couldn’t be more proud if I’d produced him myself” June was at the Gates of Heaven, and for the next year was [underlined] in [/underlined] heaven.

This ended in March 1961 when June passed a large clot of blood, and I knew at once that she would die in one year. Don’t ask me how or why, I knew instantly.

Very soon the surgeon confirmed that the cancer was back – and far worse. It was a difficult year. My own state of mind was one of continuous oppressive worry. To provide a bit of relief I took up dinghy sailing as it is almost impossible to think of anything else when sailing. This did help.

In July we planned to take a caravan holiday in Southern Ireland. I spoke to the doctor about this and he replied that s we were to go on holiday it has better be very soon (like tomorrow) as my wife would not be fit to move in two or three weeks. I now spoke with my CO (Wg Cdr Pope). who [sic] was a good friend from our days in Germany, and fully in the picture regarding June’s condition (one of [underlined] very [/underlined] few people in the know). In order to allow us to go on holiday he recalled another officer from leave; as you may imagine this upset the officer and his wife, but we could not tell them why. (After June’s death did write to him with a full explanation).

By now June was in almost continuous pain. Through our doctor she was able to visit a Harley Street specialist who hopefully could make the pain bearable through hypnosis. In fact she did obtain considerable relief through this method. But by October her condition was so bad that we decided to sleep in single beds, as much as anything to allow me to sleep. This was almost as much trauma s deciding to divorce – utterly dreadful.

I also had to gently persuade June that it would be a good idea to get Marion and Chris into boarding school to ease her load at home.

In November 1961 I arranged to be posted to RAF Uxbridge so that she could go into the RAF hospital there.

We flew from Belfast and were met a Heathrow by and RAF staff car which took us directly to the hospital. June was mildly surprised, but by now she was in a wheelchair a few more lies from me smoothed the way and considered the RAF service to be nothing less than excellent.

I was posted on to the strength of RAF Uxbridge to be near her. The RAF is a very understanding employer. Thus I was able to see her every day. She was told every day that she was beautiful and I loved her – both true. At Christmas 1961 the three children and I spent the whole day with her. They were staying with me in a married quarter on camp.

Marion was able to go to boarding school at Brentwood County High School in January 1962 and Chris was boarded by Aunty Rhoda whilst he attended Brentwood School (a Grant Maintained school) He was given a boarding place in March. June’s sister Peg (Mrs Margret Daphne Hunt) took over care of Stephen for the next five years.

A few days before June died the Duty Sister allowed me to take Stephen in to see her one evening. The Matron then complained the following evening when I was there that the baby should not have been allowed in. The Sister stood her ground and said that is was probably the last time June would see the baby. So much for the humanity of the matron. The Sister was right. I was sitting with June shortly afterwards, I has just told her I loved her so much, he struggled to say something and I said, I know, you love me too!; she relaxed and her eyes smiles. In a few seconds I realised that though her eyes were open she was not seeing. I went out to call the Sister. It was 7.45pm.

June died in Uxbridge hospital on 22 March 1962: She was 39 yrs old. We had been married 17yrs, 8 mths and 1 week. She has undergone surgery not less than twenty three times.

Our courtship had ended. The bill had come in.

Can I find a grain of comfort in all the stress and strain of those years. Only that June did not suffer mental strain in her family relationships. She loved and was loved deeply; she was utterly happy with her children and her husband for the time that she knew them, and we both knew it at the time.

5

[Page Break]

Epilogue

In the last few years, since 1990 I have learned that many cancers have a genetic basis. June was born with a cancer gene and was doomed from birth.

After June’s death a major problem has to be faced – the upbringing of our children. Marion was 14yrs, Chris 12 yrs, and Stephen 2yrs and 3 mnths. There was no question of me leaving the Royal Air Force, the problem just has to be solved. My own health was under strain and at my own request I was posted to Kuwait for a one-year unaccompanied tour. Before leaving it was necessary to cover every week of my absence especially the school holidays. June’s sister Peg took over the complete upbringing of Stephen this in addition to her own children who were the same age as Marion and Chris. My debt to her and to her husband Sam is total.

I returned to England in July 1963, did a ten-month tour in Zambia (1964-65) and spent a year (1967-68) in Iran as an ‘Operations Advisor’ in the Iranian Air Force. In October 1968 I returned to England blind in the left eye due to cataract and underwent surgery to restore a large degree of sight to the eye. The right eye went blind a year later and again surgery restored some sight, but not as good as the left eye. I did feel some bitterness as this time as having lost my wife there did seem some distinct possibility that I would lose my sight – and livelihood. In the event I was able to remuster to the Administration and Organisation Branch of the RAF in 1970.

On my return from Iran in October 1968 I was invited to dinner by RAF friends from out days in Germany. Flt Lt Peter Hinchliffe and his wife Irene. There I was introduced to Irene’s friend Mrs Alison Barclay- Jones, a widow with three children. Irene was frankly match-making, (“You haven’t done very well in finding another wife; it’s time I gave you a hand”); we all knew the score and the rules of the game. The upshot of this introduction was out marriage on 29 March 1969, Marion’s 21st birthday, with all six children at the wedding. There was no difficulty in integrating the children into one family and in 1970 we formally adopted the four children under 18 yrs. (After the authorities had checked with the children that they were in agreement to being adopted!)

Peter and Irene attended our Silver Wedding Anniversary in 1994. Our six children and five spouses attended complete with six grandchildren. In Match 1997 we celebrated our 28th anniversary.

The story owes nothing to imagination, it is entirely factual.

Hopefully my grandchildren (and perhaps their children) will find it of interest and learn of the sort of problems that may be met by a hopeful young couple as they set out on life’s journey together.

6

[Page Break]

Photographs

[Page Break]

Top

Left Miss June Eve 1942

Right Marion and Chris 1952

15 July 1944

Bridesmaids left to right

Dorothy Groom’s sister

Joyce Brides Cousin

Joyce Groom’s sister

Peggy Bride’s sister

Molly Brides’s cousin

Christmas Day 1961 at RAF Hospital Uxbridge

Collection

Citation

Jim Allen, “A Love Story by Grandad,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 22, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/16301.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.