The Exploits of Warrant Officer Arthur Pritchard

Title

The Exploits of Warrant Officer Arthur Pritchard

Description

A biography of Arthur Pritchard written by his daughter. It covers his training, operations and the night he was shot down. Despite speaking no French he was assisted to a hideout in Paris where he remained until Paris was liberated in August 1944.

Creator

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Language

Format

Two printed sheets

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

MPritchard2206805-171108-030001, MPritchard2206805-171108-030002

Transcription

THE EXPOITS OF

WARRANT OFFICER

ARTHUR PRITCHARD

By his daughter, CAROLYN PRITCHARD

My father, Warrant Officer Arthur Pritchard, passed away on May 28, 2010, aged 86 years.

His life story is of humour, luck, and courage. It is also a story of the heroism of the French people who took him under their protection at great risk to themselves.

He was born in Beach Road, Y Felinheli (Port Dinorwig), on April 13, 1924, one of seven children of Arthur and Hannah May Pritchard.

[Photograph of an airman] Arthur Pritchard in his Flight Sergeant uniform

He joined the Royal Air Force before his 18th birthday, and did his training at R.A.F. St. Athan in South Wales, where he passed out as a Flight Sergeant and was posted to R.A.F. Winthorpe in Lincolnshire, where he was introduced to his Australian crew as a Flight Engineer. On February 29, 1944 the crew joined 463 Squadron based at RAF Waddington. During their time there they completed 17 sorties over Germany and France.

On May 7, 1944, Pilot Officer Bryan Giddins and crew were posted to 97 Pathfinder Force at RAF Coningsby. They completed a further three missions, seeing action on D-Day.

On their twenty-first sortie on June 9/10, 1944, on a night raid over a railway junction at Etampes, south of Paris, pilot Officer Giddings and his crew failed to return. After releasing flares over the target their Lancaster, ND764, was hit by flak and then attacked from below by a night fighter.

Many years later when he was able to relate his story, my father recollected the moment at the time when the aircraft was hit:- “The inner or outer port side engine was on fire, - it could have been either as there wasn’t much space between the engines. The suicidal height at which we were flying, the noise, the cabin full of smoke and partially lit, communications cut, cramped conditions in the cockpit, no place to wear your parachute (it had to be stored on the floor), frantically searching for it, the rush of cold air from the open back door, trying to prise open the escape hatch at the front, every second wasted making survival more improbable, the whole episode could not have lasted for more than a few minutes, and before we realised it was a doomed machine, we would have had even less time to make our getaway. The Lancaster was not air-crew friendly!”

Out of a crew of seven there were only two survivors. Pilot officer Bryan Giddings and Navigator Bryce Webb bailed out of the blazing plane but their parachutes did not deploy in time. The Lancaster finally crashed in a field near the village of Souzy la Briche. Carrying with it the remaining three crew members – Mid-Upper Gunner John McGill, Rear-Gunner Johnny Seale and H2S Operator Charles Clement. Wireless Operator Bob Bethell had baled out through the rear door, but was captured by a German patrol and ended up in Stalag Luft 7 Bankau, near Kreulberg.

When my father and the crew failed to return from the mission my grandparents Arthur and Hannah Mary received a telegram followed by a letter advising them that their son was missing presumed killed. During the time he was missing they and the family never gave up hope that he was still alive. On one occasion the local vicar called on them to ask permission for a memorial service for him to be arranged in the village. They declined saying “Our son is coming home”.

[Underlined] Their faith was rewarded because Flight-Engineer Arthur Pritchard evaded capture. [/underlined]

The aircraft was on fire and perilously low when he bailed out and he made a heavy landing, spraining his ankle. After wondering around the French countryside with his damaged ankle and famously asking villagers for a way to the coast, he eventually arrived at the village of Egly and entered the local church. Seeing a man by the alter he told him that he was an injured RAF airman. The Frenchman was unable to speak English, but gave him some water and pointed towards a café opposite the church. On entering the café, Dad waving a 100 Franc note from his RAF kit, ordered champagne, as this was the only French word he knew. Panic broke out as

[Boxed] [Photograph of a Lancaster]

The first Lancaster bomber came off the production line at the beginning of 1942. It was designed by AVRO’s chief designer, Roy Chadwick. The plane started out as Avro Manchester, a twin engine model, but in anticipation of the greater range that Bomber Command would require as the RAF took the war to the German heartland, Chadwick modified the Manchester to house four engines. Apart from the engine changes, the Manchester design was so good it did not take much work to come up with the new model, renamed the Lancaster.

The plane came famous later of course following the well-documented Dambuster Raid, when 617 Squadron attacked the Eder and Ruhr dams. [/boxed]

[Page break]

[Boxed] 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron,

Royal Air Force,

CONINGSBY,

Lincolnshire.

10th June, 1944.

Dear Mr. Pritchard,

It is with deep regret that I must confirm that your son, Sergeant A. Pritchard, failed to return from operations this morning, the 10th June, 1944, and I wish to express the great sympathy which this Squadron feel with you during the [indecipherable] any news comes through.

Your son was taking part in an operation against a military target and [indecipherable] France, Flight Engineer of the aircraft. No news has been received since the aircraft left base last night – we can only hope that they had the chance to bale out and are safe, even as prisoners of war.

Sergeant Pritchard had only been serving with this Squadron for a short while, but during that period he was able to operate with us on the opening of the Second Front. He had operated with another Squadron prior to coming here, and had taken part in fifteen sorties, many of which were against major objectives in Germany. On this occasion he was working with his usual crew. Your son was keen and capable as a flight engineer, and he and his crew will be a great loss to the Squadron; we shall all miss them very much.

It [indecipherable] to explain that the request in the telegram notifying you of this casualty was [indecipherable] your son’s chance of escape being prejudged by [indecipherable] he is still at large. This is not to say that any information about him is available, but us a precaution adopted in the case of all personnel reported missing.

His kit and personal effects are being carefully collected and will be sent to the R.A.F. Central Depository, Colebrook, Slough, from whom you will hear in due course.

If any news is received you will be communicated with immediately, and in the meantime I join with you in hoping that we shall soon hear favourable news of your son and the remainder of the crew.

Yours sincerely,

[Signature]

Squadron Leader, Commanding,

No. 97 (Straits Settlements)

[Underlined] Squadron, R.A.F. CONINGSBY. [/underlined]

Mr. A. Pritchard,

10, [indecipherable];

PORT [indecipherable]

N. Wales.

[/boxed]

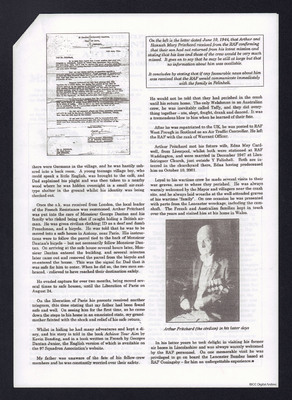

[Boxed] On the left is the letter dated June 10, 1944, that Arthur and Hannah Mary Pritchard received from the RAF confirming that their son had not returned from his latest mission and stating that his loss and those of the crew would be very much missed. It goes on to say that he may be still at large but that no information about him was available.

It concludes by stating that if any favourable news about him was received that the RAF would communicate immediately with the family in Felinheli. [/boxed]

there were Germans in the village, and he was hastily ushered into a back room. A young teenage boy, who could speak a little English, was brought to the café, and Dad explained his plight and was then taken to a nearby wood where he was hidden overnight in a small air-raid-type shelter in the ground whilst his identity was being checked out.

Once the o.k. was received from London, the local leader of the French Resistance was summoned. Arthur Pritchard was put into the care of Monsieur George Dantan and his family who risked being shot if caught hiding a British airman. He was given civilian clothing; ID as a deaf and dumb Frenchman, and a bicycle. He was told that he was to be moved to a safe house in Antony, near Paris. His instructions were to follow the parcel tied to the back of Monsieur Dantan’s bicycle – but not necessarily follow Monsieur Dantan. On arriving at the safe house several hours later, Monsieur Dantan entered the building, and several minutes later came out and removed the parcel from the bicycle and re-entered the house. This was the signal for Das that it was safe for him to enter. When he did so, the two men embraced, – relieved to have reached their destination safely.

He evaded capture for over two months, being moved several times to safe houses, until the Liberation of Paris on August 24.

On the liberation of Paris his parents received another telegram, this time stating that my father had been found safe and well. On seeing him for the first time, as he came down the steps to his home in an emaciated state, my grandmother fainted with the shock and relief of his safe return.

Whilst in hiding he had many adventures and kept a diary, and his story is told in the book Achieve Your Aim by Kevin Bending, and in a book written in French by Georges Dantan Junior, the English version of which is available on the 97 Squadron Association’s website.

My father was unaware of the fate of his fellow-crew members and he was constantly worried over their safety. He would not be told that they had perished in the crash until his return home. The only Welshman in an Australian crew, he was inevitably called Taffy, and they did everything together – ate, slept, fought, drank and danced. It was a tremendous blow to him when he learned of their fate.

After he was repatriated to the UK, he was posted to RAF West Freugh in Scotland as an Air Traffic Controller. He left the RAF with the rank of Warrant Officer.

Arthur Pritchard met his future wife, Edna May Cardwell, from Liverpool, whilst both were stationed at RAF Waddington, and were married in December 1947 at Llanfairisgaer Church, just outside Y Felinheli. Both are interred in the churchyard there, Edna having predeceased him on October 10, 2001.

Loyal to his wartime crew he made several visits to their war graves, near to where they perished. He was always warmly welcomed by the Mayor and villagers near the crash site, and he always laid wreaths at the well-attended graves of his wartime “family”. On one occasion he was presented with parts from the Lancaster wreckage, including the cam-shaft. The French and Australian families kept in touch over the years and visited him at his home in Wales.

[Photograph of a man wearing medals] Arthur Pritchard (the civilian) in his latter days

In his latter years he took delight in visiting his former air bases in Lincolnshire and was always warmly welcomed by the RAF personnel. On one memorable visit he was privileged to go on board the Lancaster Bomber based at RAF Coningsby – for him an unforgettable experience.

WARRANT OFFICER

ARTHUR PRITCHARD

By his daughter, CAROLYN PRITCHARD

My father, Warrant Officer Arthur Pritchard, passed away on May 28, 2010, aged 86 years.

His life story is of humour, luck, and courage. It is also a story of the heroism of the French people who took him under their protection at great risk to themselves.

He was born in Beach Road, Y Felinheli (Port Dinorwig), on April 13, 1924, one of seven children of Arthur and Hannah May Pritchard.

[Photograph of an airman] Arthur Pritchard in his Flight Sergeant uniform

He joined the Royal Air Force before his 18th birthday, and did his training at R.A.F. St. Athan in South Wales, where he passed out as a Flight Sergeant and was posted to R.A.F. Winthorpe in Lincolnshire, where he was introduced to his Australian crew as a Flight Engineer. On February 29, 1944 the crew joined 463 Squadron based at RAF Waddington. During their time there they completed 17 sorties over Germany and France.

On May 7, 1944, Pilot Officer Bryan Giddins and crew were posted to 97 Pathfinder Force at RAF Coningsby. They completed a further three missions, seeing action on D-Day.

On their twenty-first sortie on June 9/10, 1944, on a night raid over a railway junction at Etampes, south of Paris, pilot Officer Giddings and his crew failed to return. After releasing flares over the target their Lancaster, ND764, was hit by flak and then attacked from below by a night fighter.

Many years later when he was able to relate his story, my father recollected the moment at the time when the aircraft was hit:- “The inner or outer port side engine was on fire, - it could have been either as there wasn’t much space between the engines. The suicidal height at which we were flying, the noise, the cabin full of smoke and partially lit, communications cut, cramped conditions in the cockpit, no place to wear your parachute (it had to be stored on the floor), frantically searching for it, the rush of cold air from the open back door, trying to prise open the escape hatch at the front, every second wasted making survival more improbable, the whole episode could not have lasted for more than a few minutes, and before we realised it was a doomed machine, we would have had even less time to make our getaway. The Lancaster was not air-crew friendly!”

Out of a crew of seven there were only two survivors. Pilot officer Bryan Giddings and Navigator Bryce Webb bailed out of the blazing plane but their parachutes did not deploy in time. The Lancaster finally crashed in a field near the village of Souzy la Briche. Carrying with it the remaining three crew members – Mid-Upper Gunner John McGill, Rear-Gunner Johnny Seale and H2S Operator Charles Clement. Wireless Operator Bob Bethell had baled out through the rear door, but was captured by a German patrol and ended up in Stalag Luft 7 Bankau, near Kreulberg.

When my father and the crew failed to return from the mission my grandparents Arthur and Hannah Mary received a telegram followed by a letter advising them that their son was missing presumed killed. During the time he was missing they and the family never gave up hope that he was still alive. On one occasion the local vicar called on them to ask permission for a memorial service for him to be arranged in the village. They declined saying “Our son is coming home”.

[Underlined] Their faith was rewarded because Flight-Engineer Arthur Pritchard evaded capture. [/underlined]

The aircraft was on fire and perilously low when he bailed out and he made a heavy landing, spraining his ankle. After wondering around the French countryside with his damaged ankle and famously asking villagers for a way to the coast, he eventually arrived at the village of Egly and entered the local church. Seeing a man by the alter he told him that he was an injured RAF airman. The Frenchman was unable to speak English, but gave him some water and pointed towards a café opposite the church. On entering the café, Dad waving a 100 Franc note from his RAF kit, ordered champagne, as this was the only French word he knew. Panic broke out as

[Boxed] [Photograph of a Lancaster]

The first Lancaster bomber came off the production line at the beginning of 1942. It was designed by AVRO’s chief designer, Roy Chadwick. The plane started out as Avro Manchester, a twin engine model, but in anticipation of the greater range that Bomber Command would require as the RAF took the war to the German heartland, Chadwick modified the Manchester to house four engines. Apart from the engine changes, the Manchester design was so good it did not take much work to come up with the new model, renamed the Lancaster.

The plane came famous later of course following the well-documented Dambuster Raid, when 617 Squadron attacked the Eder and Ruhr dams. [/boxed]

[Page break]

[Boxed] 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron,

Royal Air Force,

CONINGSBY,

Lincolnshire.

10th June, 1944.

Dear Mr. Pritchard,

It is with deep regret that I must confirm that your son, Sergeant A. Pritchard, failed to return from operations this morning, the 10th June, 1944, and I wish to express the great sympathy which this Squadron feel with you during the [indecipherable] any news comes through.

Your son was taking part in an operation against a military target and [indecipherable] France, Flight Engineer of the aircraft. No news has been received since the aircraft left base last night – we can only hope that they had the chance to bale out and are safe, even as prisoners of war.

Sergeant Pritchard had only been serving with this Squadron for a short while, but during that period he was able to operate with us on the opening of the Second Front. He had operated with another Squadron prior to coming here, and had taken part in fifteen sorties, many of which were against major objectives in Germany. On this occasion he was working with his usual crew. Your son was keen and capable as a flight engineer, and he and his crew will be a great loss to the Squadron; we shall all miss them very much.

It [indecipherable] to explain that the request in the telegram notifying you of this casualty was [indecipherable] your son’s chance of escape being prejudged by [indecipherable] he is still at large. This is not to say that any information about him is available, but us a precaution adopted in the case of all personnel reported missing.

His kit and personal effects are being carefully collected and will be sent to the R.A.F. Central Depository, Colebrook, Slough, from whom you will hear in due course.

If any news is received you will be communicated with immediately, and in the meantime I join with you in hoping that we shall soon hear favourable news of your son and the remainder of the crew.

Yours sincerely,

[Signature]

Squadron Leader, Commanding,

No. 97 (Straits Settlements)

[Underlined] Squadron, R.A.F. CONINGSBY. [/underlined]

Mr. A. Pritchard,

10, [indecipherable];

PORT [indecipherable]

N. Wales.

[/boxed]

[Boxed] On the left is the letter dated June 10, 1944, that Arthur and Hannah Mary Pritchard received from the RAF confirming that their son had not returned from his latest mission and stating that his loss and those of the crew would be very much missed. It goes on to say that he may be still at large but that no information about him was available.

It concludes by stating that if any favourable news about him was received that the RAF would communicate immediately with the family in Felinheli. [/boxed]

there were Germans in the village, and he was hastily ushered into a back room. A young teenage boy, who could speak a little English, was brought to the café, and Dad explained his plight and was then taken to a nearby wood where he was hidden overnight in a small air-raid-type shelter in the ground whilst his identity was being checked out.

Once the o.k. was received from London, the local leader of the French Resistance was summoned. Arthur Pritchard was put into the care of Monsieur George Dantan and his family who risked being shot if caught hiding a British airman. He was given civilian clothing; ID as a deaf and dumb Frenchman, and a bicycle. He was told that he was to be moved to a safe house in Antony, near Paris. His instructions were to follow the parcel tied to the back of Monsieur Dantan’s bicycle – but not necessarily follow Monsieur Dantan. On arriving at the safe house several hours later, Monsieur Dantan entered the building, and several minutes later came out and removed the parcel from the bicycle and re-entered the house. This was the signal for Das that it was safe for him to enter. When he did so, the two men embraced, – relieved to have reached their destination safely.

He evaded capture for over two months, being moved several times to safe houses, until the Liberation of Paris on August 24.

On the liberation of Paris his parents received another telegram, this time stating that my father had been found safe and well. On seeing him for the first time, as he came down the steps to his home in an emaciated state, my grandmother fainted with the shock and relief of his safe return.

Whilst in hiding he had many adventures and kept a diary, and his story is told in the book Achieve Your Aim by Kevin Bending, and in a book written in French by Georges Dantan Junior, the English version of which is available on the 97 Squadron Association’s website.

My father was unaware of the fate of his fellow-crew members and he was constantly worried over their safety. He would not be told that they had perished in the crash until his return home. The only Welshman in an Australian crew, he was inevitably called Taffy, and they did everything together – ate, slept, fought, drank and danced. It was a tremendous blow to him when he learned of their fate.

After he was repatriated to the UK, he was posted to RAF West Freugh in Scotland as an Air Traffic Controller. He left the RAF with the rank of Warrant Officer.

Arthur Pritchard met his future wife, Edna May Cardwell, from Liverpool, whilst both were stationed at RAF Waddington, and were married in December 1947 at Llanfairisgaer Church, just outside Y Felinheli. Both are interred in the churchyard there, Edna having predeceased him on October 10, 2001.

Loyal to his wartime crew he made several visits to their war graves, near to where they perished. He was always warmly welcomed by the Mayor and villagers near the crash site, and he always laid wreaths at the well-attended graves of his wartime “family”. On one occasion he was presented with parts from the Lancaster wreckage, including the cam-shaft. The French and Australian families kept in touch over the years and visited him at his home in Wales.

[Photograph of a man wearing medals] Arthur Pritchard (the civilian) in his latter days

In his latter years he took delight in visiting his former air bases in Lincolnshire and was always warmly welcomed by the RAF personnel. On one memorable visit he was privileged to go on board the Lancaster Bomber based at RAF Coningsby – for him an unforgettable experience.

Collection

Citation

Carolyn Pritchard, “The Exploits of Warrant Officer Arthur Pritchard,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 26, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/22871.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.