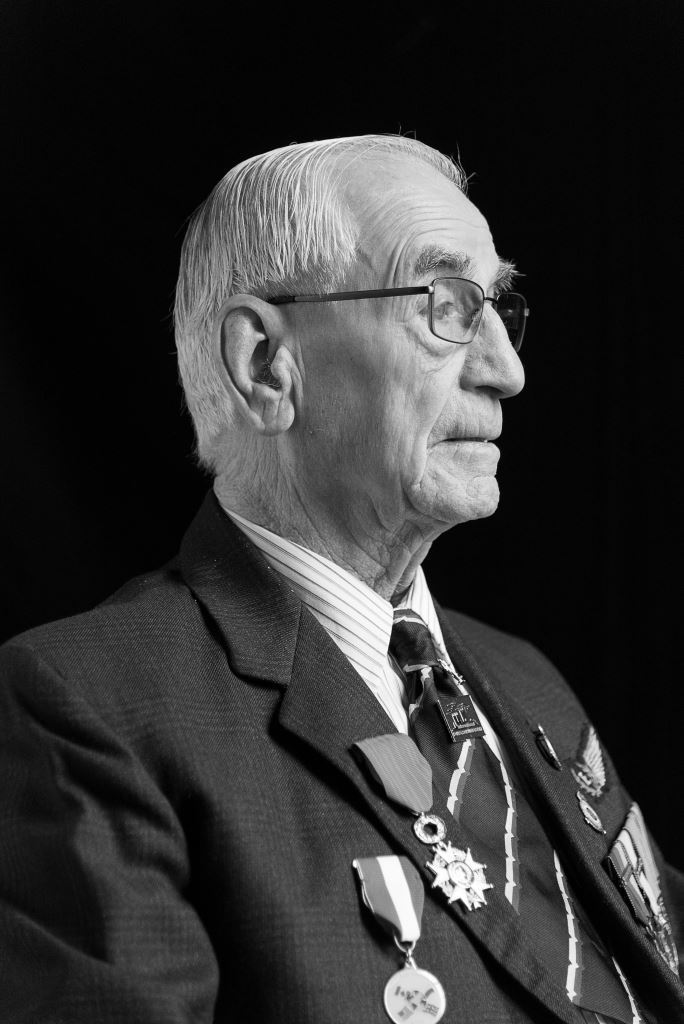

Interview with Harry Parkins. One

Title

Interview with Harry Parkins. One

Description

Before the war, Harry Parkins worked in furniture restoration in Hackney, before later selling bomb-damaged goods in Bethnal Green, working for an engineering firm in Islington until it was bombed and finally as an invoice and warehousing clerk before volunteering for the Royal Air Force. He trained as a flight engineer and flew on three operations with Pilot Officer Jackson before his own crew became operational at RAF East Kirkby. He survived a mid-air collision and later crashed in a Stirling whilst an instructor, at a Heavy Conversion Unit. He then returned to operations at RAF Fiskerton. In one incident, his pilot feathered three engines of his Lancaster on the return from bombing Berchtesgaden. He also discusses lack of moral fibre, his experiences of Victory in Europe Day and Victory over Japan Day celebrations in Lincoln and travelling to Pomigliano d’Arco to bring soldiers back from Italy. Post-war he was a salesman, selling ‘Newnes Pictorial Knowledge’, type-writers, appliances and electrical spares.

Creator

Date

2015-06-05

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:52:21 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

AParkinsH150605

Transcription

DE: Harry, could you tell me a little bit about your early life?

HP: Yes, when I lived in London, I lived near Mare Street, Hackney and at the bottom of our street there was a building where they, actually they were faking antique furniture, and I got talking to the son of the owner, he said we’d like someone to come in and get tea and cakes for the workers to save them going out so I said OK I can do that on, after school hours and at the weekends whenever they were working and the owner was called a Mr Chiswell and he told me that the White Horse Inn was where Dick Turpin used to come when the police were after him and he’d gallop in through the door and down and there was a tunnel that, that went all over London, a secret tunnel and he said and that’s why they couldn’t catch him, and he took me down and showed me the tunnel which was quite creepy really, and I got on famous [sic] with Mr Chiswell, and he had a son that was in charge of the French polishing side of the furniture cos they didn’t have sprays in those days and I learnt quite a lot about French polishing and what they did with the furniture, and they gave me a piece of wire with some nuts, all different size nuts threaded round it, and my job was to run it up and down on the edges of the chairs to make them look old, and down the legs, which was interesting, and they had a little drill where they used to drill worm holes as well, it was marvellous what they could do.

An, an incident that they told me about was, a very rich family had gone on holiday and their son had had a rave up party in the big house and wrecked some of the furniture, and they got to know about Mr Chiswell and they sent their man with some of the chairs for him to bring back up to normal, and he used to get the cloth from theatres where those big curtains used to go across, they were never washed or anything and eventually they had moth holes and he used to buy these to replace the [slight laugh] chair covers and I used to go and watch the carvers who were very marvellous at carving the intricate things on the chairs that they did in those days and he said this man came with a wheelbarrow with these chairs on and Mr Chiswell said ‘OK leave them with me, come back in, probably a week and we’ll have them all ready for you’ so off he goes, and when they were ready Mr Chiswell liked these chairs, I think they were Baxondale or some famous chairs, that he decided to have a set made for himself, and when this fella came back for them he told the young man working in the shop that he had to go away on business so when the man came for the chairs, make sure he took them from downstairs, not upstairs, so when the fella came the young man forgot which was which [laughs] and he took him upstairs so they were loaded and off the fella went, well when Mr Chiswell came back he said ‘where’s my chairs gone?’ and the lad said ‘I thought that was the ones that belonged to the family’, he said ‘no, you’ll have to go round and tell them that you made a mistake and we want those chairs back and they can have the originals’, but they refused, the son refused to let them come back so he was landed with the real genuine antiques, so that was interesting, and then just round the corner there used to be, I don’t know if it’s still there, a big church, and my family were into going to Sunday school and the teacher there, she said to me, ‘one day you’re gonna [sic] have to start work or be called up, what do you intend to do?’ so I said well I’m very good at drawing and printing, so she said ‘my uncle has got an engineering firm near Kings Cross, she said when you’re ready I’ll put a word in for you’. Well in between that, my family moved because the council were going to knock all these houses down and build flats there so we moved near to Bethnal Green. There used be, a fella that sold everything, if you’ve ever watched, that show on the television, Arkwright? With all the stuff he had in the shop,

DE: Open all Hours?

HP: Open all Hours, it was very similar to that and he had a shop, which was really a house converted and all the stuff that was in there were pots and pans, paint, paint brushes, you name it, he’d got everything, and he used to go out where places were bombed and buy all the stock that had been damaged, and he, I got the job there after school hours again which was from about five o’clock up to ten o’clock every night ‘cause [sic] they were open as late as that, and he was teaching me how to sell this stuff and how to sort it out, and if there were saucepans, they would always be a set but some had chips on them because in those days they were all enamel, so the worst ones were put here, the next lot there, and those that were fairly good were the best ones so they all had different prices and I had to learn that [slight laugh] and how to do all this, and it was the same with cups and saucers, the same thing and I got very good at doing all this and when I used to go there, especially on a Saturday, he’d give me an an apron with two pockets, give me a few pounds in the pockets and he’d disappear out the back sorting things out and I was serving customers and taking the money and giving them change, so I felt really good doing this, and then the war was on and the German bombers decided to bomb the docks, well Bethnal Green is not far from the docks so they were shooting howitzer guns on wheels up and down the street firing them and you could hear the shrapnel coming down on the roof, and Bill said to me, ‘I think we better pack up’ he said, ‘because you need to get home especially with the bombing’ so I said ‘OK’ and I started bringing all the stuff in and he, he seemed to vanish, and a policemen come along and said ‘what you doing son?’ and I said ‘I’m taking all this stuff in to the back, can’t leave them outside’ so he said ‘you leave that be and get off home’, he said ‘where’s the boss?’, I said ‘I think he’s out the back making a cup of tea’, he said ‘well don’t forget as soon as he comes up tell him you want your cash and you’re going home’ so I thought OK and I carried on doing this, where the stairs were, he used to hang big galvanised baths, on hooks, I, I thought, well I got everything inside and I thought I wanted my money and get off home, and as I walked down to the back one of these baths was down and I was walking on top of it, on top of the bottom going down to the bottom to see if he was in the kitchen making tea but he wasn’t there anywhere and I thought where on earth’s he gone? And I kept shouting up the stairs, going up the stairs in to all the rooms, couldn’t find him and as I was coming down I saw this bath moving, he’d got underneath the bath [laughing] he didn’t know what to say to me, he said ‘here’s your cash, you go home son’. That was the funniest thing that happened to me.

And then of course it was nearly time I was going to get called up, so the Sunday school teacher said ‘I’ve made you an appointment to be at my Uncle who owns this business’, engineering business it was, so he said ‘I’ll tell you where it is’, I got on my bike and rode down to Kings Cross, found the street where the place was and this fella interviewed me and he said ‘I like you’, he said ‘you seem to be able to write fairly decently’, he says ‘so we could teach you draftmanship and engineering but first of all you’ll go on the tools’, which was a capstan operated machine where you are doing this sort of thing and I was making Morse code tappers, and I was getting on well with this and the bombing was still going on, and my father was a bit worried me going all that way, so he said ‘look after yourself and if anything happens you get off home quick or get down to the air raid shelter’, well the, the foreman, I found out was in charge of the other lads that were on these machines were all Barnados homes boys, so he used to swear and curse and god knows what at the, I felt sorry for them, ‘cause [sic] they couldn’t complain, at least they got a job. And then one day it was bank holiday and the foreman came up to me and he said ‘you realise you have to work all through the bank holiday?’, I said ‘no, I didn’t know that’ I said ‘I thought it was only a five day week’ so he said, ‘ you be here on bank holiday Monday’, well when I got home my dad was a great union man, he said ‘No way are you going in on bank holiday Monday’, so I said ‘well I’ll probably get the sack or put in prison or something’ [laughs] I didn’t know what would happen to me. Anyways, he stopped me from going and we went down into Epping Forrest while he went into the pub and he had a drink and we had a meal and played around and then came home. When I went in on the Tuesday, all hell had broke loose, I was going end up in jail because nobody was on my particular machine and the person they put on it did something wrong, the belts came down and stopped all the work going on, but anyways I got over that and then [short pause] I was riding into work one Monday morning, half way along Kings Cross road a policemen and an air raid warden came up to me and they said ‘where the hell do you think you’re biking to son?’, I said ‘Islington engineering’ and they said ‘well you bloody well go back home because it’s not there anymore’, it’d been blown up, been bombed so I went back home, just messed around, didn’t do anything particular, and usually I was always in for my evening meal after my father, this time I was in before him and he looked at me and he said ‘how is it you are in at this time? Have you got the sack?’ I said ‘No, firm’s been bombed’ so he said to me ‘I could see [emphasis] this happening, what you been doing? have you found another job?’ I said ‘no, I’ve just been messing around’, ‘Right, tomorrow morning after the air raid warning all clear goes, you are getting on your bike and you don’t come home until you’ve got a job’, and that’s how they were in those days.

So next morning, my Mum packed me up a little lunch and said cheerio to me and I went down one of the longest roads, actually I think it’s near where they put this Olympic business in London, and, all along this terrific long road there was all different industries, all the way along, so I thought all I can do is stop at the first one and go right the way to the end, I knocked doors, ‘how old are you son?’, ‘18’, ‘no, we can’t take you on’, this happened all the way right to the end, right to the end, I just sat on the curb stone more or less in tears that I hadn’t got a job, and ate my sandwiches, I didn’t have a drink so I thought I’ll start down the other side of the road, the same all the way along until the huge firm of transport and I looked through the gates and I thought well surely they can do with a van boy or something like that, but I couldn’t get in so I went a bit further and there was a little door, I pushed this door and it came open and there were some stairs going up so I thought I’ll go up the stairs, went up the stairs and there was a nice young lady there and she said ‘hello, what can I do for you son?’ And I told her more or less what I’ve told you and I was nearly in tears and she said ‘sit down and have a cup of tea’, so I sat down and she said, ‘what would you like to do’ and I said ‘anything as long as it’s a job because I can’t go home until I got a job’ [laughter] she said ‘really?’ I said ‘yeah my dad is very strict’ so she said ‘well we want an invoice clerk’, she said ‘so we need someone straight away, would that be alright?’ Well I didn’t even know what an invoice was [laughs] so I told her this so she said ‘well I’ll get an invoice out, I’ll write it out and I’ll show you what you have to do and you copy what I’ve done’, so I did this, copied what she’d put out and she said ‘Ooh you do write good, well done, can you wait until quarter past five?’ well it was five o’clock then so I said ‘yes, why?’ she said ‘well, I’ll give you a chance to see the manager’, she said ‘and when you go in, the first thing he’s going to say is would you write your name and address and he’ll look at it and then he’ll ask you have you any idea of writing out invoices and you can say yes can’t you? [laughs] So this is what happened and at the end of it he said right well we need someone straight away when can you start?, I said ‘tomorrow morning’, he said ‘Good, if you can get here at six o’clock in the morning, that’ll be just after the air raid warning said the all clear’, he said ‘you’ve got yourself a job’, and my dad had always taught me how much, what are we going to get paid so I said ‘well you’ve mentioned all these things but you haven’t said what I’ll get paid’, so he said ‘well it’ll be thirteen shillings a week, is that OK?, Monday till Friday, no Saturday’ so I said ‘yes that’ll be fine’ because I was only getting eleven shillings learning to be an engineer so that was all settled, and I got on well there and I got on well with some of the lads, and after a while one of the foremen happened to come into the office and he said ‘we need someone down on the bay’, so the manager said ‘why?’, he said ‘well we lost two people, they’ve been called up so we need someone to write out the delivery notes for the lorry drivers’, so on this side there was the lorry drivers from, east end, north, west, where drivers got stuff from the other side that come from up north on the big lorries that were opened in the night time and they wanted their deliveries all written out ready to shoot off when they came in, so the manager said ‘well this lad’s good at writing’, so he said ‘good, follow me’ and he took me down the bay and showed me all what I wanted to do, so I said ‘does that make any difference to my pay?’ so he said ‘yes, I think so, what do you get at the moment?’ I said ‘thirteen shillings a week’, he said ‘we’ll make that up to two pound, would that be Ok?’ [laughs] so I said ‘marvellous’ and that was the start of that, so I was working on the bay and in the office and then as lads were being called up, they had women coming in doing the trucking from the night shift to the day shift and they were getting all mixed up with the East End, the West End and where to put the goods, so I said to this foreman ‘if you get me some big cards, like they have on the underground I could write what these places were for each bay’, so he said ‘you think you could do that?’, I said ‘yes, easy’ so he got me all these big cards so I was doing some of that at home and my Dad said ‘are you getting overtime?’ [laughs] I said ‘no!’ [continues laughing] Dad said ‘when you see the foreman ask him what over time you getting’ so I cheekily asked him ‘do I get any overtime for doing all this?’, he said ‘certainly, haven’t we told you?’, I said ‘no’ he said ‘right, when you go to clock out, don’t clock out, bring me your card and I will enter so many hours each day for you’ so it ended up I was getting three pound fifteen a week which was more than my dad was earning as a scaffolder.

And then some of the girls used to come in late, which was booed [sic] upon. So I said, well, I do a bit of watch making in my spare time, I’m trying to teach myself how to repair watches and clocks so he said ‘Good’, he took me to this girl, I think she was a foreigner, and she couldn’t get in early, so he said ‘well you are going to get the sack so, what’s your problem, your real problem?’ she said ‘my alarm clocks broken’ so he said ‘would you bring it tomorrow, give it to this lad, he’ll take it home and he’ll mend it’, so I thought I hope I can mend it [laughs] and I mended this clock anyways and from then on she was never late. And this got to the manager of the place, and he called me in one day and said ‘I understand you can mend clocks, what about pendulum clock’? I said ‘yeah, I think so, as long as I can get the bits from somewhere’ so he said ‘right, I’ll send a van round with this clock’ [laughs] it was a great big clock ‘to your house’ so I took it in, had a look at it and I found there wasn’t really anything broken it was just clogged up with muck, only needed a real good clean and an oil and it worked perfect, so I kept it a few days so to make it seem as so it was a hard job [laughs] and when I went back I said ‘your clocks OK for your van driver to come and pick it up’, which he did, took it into his office and he says ‘set it up’, so I set it up and it was working perfect, so he said ‘what do you think I ought to pay you?’, well I had no idea what it’s worth so I said ‘maybe about a fiver’ and he said ‘there’s a tenner son, thank you’. And that was really good.

And then after I think about a year or eighteen months, one of the lads I got really friendly with, we used to be having our lunch ‘cause [sic] they had soup at the canteen, we were talking about the war and what was going to happen, both the same age, and I said ‘we are going to get called up any minute now’, so he said ‘what do you want to go in for?’ he said ‘because if you volunteer you near enough get what you want but if you are called up you end up in the army’ and I said ‘ooh I don’t want to go in the army’ ‘cause me [sic] Dad’s told about me stories of being in the army so he said ‘what about the navy?’ so I said ‘ooh I don’t know, I can only swim across the canal’ [laughs] I never tried any further, so I said ‘I know’, I said, ‘I think it is safer in the air than on the ground, I said ‘I reckon I’ll volunteer for the RAF’ he said ‘that’s a good idea, when we finish lunch we’ll go down the road and both volunteer’ and that’s what we did, and I ended up getting in the air force but he didn’t because he had something wrong with his down below and it wouldn’t except him but when we went through the medical and came out again I said ‘I’ve passed all OK’ and he said ‘so have I’, and his name was John Smith and I never saw him again, so I don’t know what happened to him.

But I ended up a week later being called up, I was, up to, where was it, where London Zoo is, and on the right hand side there was super flats where film stars used to stay, and that had been commandeered by the air force and we were billeted in them and it was fabulous, I thought this is good in the air force [slight laugh]. We had all the inoculations and all that done and the square bashing and at the time in the paper and on the radio there used to be a fella called Alvar Lidell and he used to sing out ‘This is Alvar Lidell bringing you news’, and in the paper it said this is “Alvar Lidell in the air force stamping out on the playground” and he was there when I was there, but I never actually met him, and I suppose we were there for about a month, six weeks or something learning all the things you had to do, then we were posted down to Saint Athan’s, and that’s where they said you can either be a gunner and I said ‘No way’, you go before some group captains interviewing you and one of them said ‘it’s got down here you can mend clocks, is that right?’ I said ‘yes, and watches’ so he said ‘well that sounds like a bit of engineering, so maybe a flight engineer will be Ok for you’, well I didn’t exactly [emphasis] know what it was but I said ‘yes, that’s far better than a gunner’, and I got all the training on a Stirling bomber and from there when you passed out we went to a conversion unit where you were supposed to meet your crew, well your crew were, flyers who had been on twin engine bombers and converting onto four engine bombers, well the idea was you went into the bar, and there was a big area there where you mingled with some of these bomber crews, and they didn’t like the idea of having an engineer coming onto their crew so the first thing they would ask you is how many flying, flying hours have you got, well you had none, so you didn’t know if you would be sick or anything, so I cottoned on to this so what I did, is I kept going to other pilots that were flying and said ‘could I have a lift’, and I got about 25 hours in, so when I went into this mixture, a fella came up to me and said ‘I heard you talking’, he said ‘you sound like us’, so I said ‘what do you mean, I sound like you?’ [laughs] he said, ‘well we are Australian, New Zealand crew and’ he said ‘you sound like an Australian, where do you come from?’ so I said ‘Hackney’, he said ‘Ackney [emphasis], A? Ackney?’ I said ‘yes’ he said ‘where’s that?’ I said ‘in London’ so he said ‘what’s your name, mate? I said ‘Harry’ he said ‘Hackney Harry, that sounds good, I’ll take you to meet the crew’, and they were all sat round drinking pints and introduced me to them all, introduced me to the pilot and he said ‘what you drinking, Harry?’ and I never drank at all, so I said ‘I don’t drink’ so the rear gunner who’s Australian, who, the one who’d picked me up, he said ‘you better have something Harry or else you’ll get chucked out before you’ve even joined’ [laughs] so I said ‘I’ll have whatever you’re drinking’, they were drinking black and tan, which was a pint of half Guinness and half mild, so that was OK. The mid-upper gunner said ‘do you want a fag?’ I said ‘I don’t smoke’ so the navigator said ‘what the bloody hell do you do on Sundays?’ [laughs] and that broke the ice and I was in with the crew.

So we did a few cross countries on Stirling’s, then they said we were being converted onto Lancasters, and that was good because the Stirling was considered the flying submarine and the Lancs could get up higher. So we did a couple of cross countries on the Lancaster and then we were sent to East Kirkby to be on the proper squadron, well when we got there, I said to the engineering officer, I said ‘I’ve been trained all this time on Stirling’s which is all electric, Lancaster’s are all hydraulic and I don’t feel 100 percent to go on ops’, ‘Leave it with me’ he said, and nothing happened for a few days and it was bank holiday Monday so, we were all lined up at the bus stop to go to Boston, it was our first day out to Boston, have some beers out there, and then, oh before that, this drinking business, the rear gunner said to me ‘our pilot has never been drunk in all the time we’ve known him so when, if you don’t drink and you don’t want to get drunk do what the pilot does’ so I said ‘OK’ and the pilot said ‘Cheers Harry’ [makes a sound of drinking] and he was nearly to the bottom of the glass, well I tried [drinking sound], I was only a finger nail down, by the time I had got through the pint I was more or less drunk [laughs]. Anyways going back to this, at the squadron, a group captain’s car came round and his man got out and he said ‘is there a Sergeant Parkins anywhere along here?’ I said ‘yes sir’, he said ‘come over here’, I said ‘I was just going into Boston, he said ‘you’re not, the group captain wants a word with you’ so I had to get in the car and he drove round the airdrome and nobody said a word and then all of the sudden the group captain said ‘I hear you wanted a bit more training on the Lancaster’s, is that right?’ I said ‘yes sir’ he said ‘good, I’m taking you down to briefing, he said ‘you are on ops tonight’, I said ‘but my crew are not ready’, he said ‘well this crew is and they’ve lost their engineer, he’s gone lack of moral fibre disappeared so they said ‘you’re on briefing with him’, and his name was Pilot Officer Jackson, so I met him and he said we are flying off at a certain time and he said ‘this is John, Bill, Jack whatever, the crew’ and off we went on ops. It was a French target, luckily we got there, got back OK and I felt chuffed because I’d done one more than the crew. The captain was supposed to do one to become a captain before the crew, well I’d beaten the pilot, so I felt, I felt really good, daft as it sound. But then the next couple of nights we were on ops again, my pilot was gonna [sic] do his, what they call the first sticky and this Pilot Officer Jackson came up to me and he said ‘the crew liked you, would you like to come with us again?’ and I thought that’s two I have in front so I said ‘Yes’ [emphasis], that’s a bit crazy, so I went off, got back OK and my pilot got back OK so then a few days after we were on ops again, Pilot Officer Jackson came over to me and he said, ‘you’re an experienced flight engineer on bomber command now, are you coming back with me?’ so I said ‘oh I don’t know, I like my crew, Australian and New Zealanders and they like me so I said ‘no, I’ll go with my own crew tonight’, so off we both go, he never came back so how lucky was three to me, and three has always been lucky, I was born on the third of October, I lived at 13 Churchill Walk, and it was the only house in all the street where a bomb had dropped in the next street and all the windows were shattered except ours, number thirteen, so I’ve always felt three and thirteen have been lucky to me. So that was the beginning of my bombing career and I ended up doing thirty six at East Kirkby, including a mid-air collision.

DE: Really?

HP: Yep. Where bomber pilots were coming back off ops, they should follow the circuit of another airdrome round, the circuit, not shoot straight across, well this particular pilot decided, we’d come back from Stuttgart, all safe and sound and he come shooting across, he took the H2S cupola off and the tail wheel off, and there was such a thunder to us, and I said ‘that was hell of a slip stream’ and it made the crew laugh and in all the fear we had it took it away and the other one went in and blew up, all got killed and we managed to land with sparks flying up all over the place.

DE: Did the rear gunner come forward for the landing?

HP: No, he stayed in his seat screaming blue murder, ‘I’m gonna catch fire’ and that’s where the saying was where the gunner shouted out ‘what colours blood skip?’ ‘cause [sic] he’d done it in his pants [laughing]. That’s seven days survivors leave.

DE: Is that what happened is it?

HP: Yes, and then after that as I say we carried on, we did, I think it was the fifth or the sixth op, was to go to Munich but we were briefed different to the other crew which were going to Munich, we were told to stay behind, we stayed behind and the squadron leader said, ‘well we’re keeping you behind because when you taxi round and we want you to stop the engines and have that little drop of fuel put in because if you’re lucky to get back, you’ll have to land down south because you wouldn’t have enough fuel to get back to East Kirkby so we said ‘why?’ he said ‘because you are not going straight to Munich, you’re going right down over the alps, right down to Italy, turning round and coming back up to fool the Germans. Well we did this, and luckily we were safe. On the way back the rear gunner shouted out ‘Harry’, he said ‘you know we are on leave tomorrow’, you got seven days leave, every six weeks if you were lucky, so I said ‘yeah, it seems a shame’ he said ‘work out the fuel’, ‘cause [sic] I was in charge of that, he said ‘see if we can get back to East Kirkby’ so I said ‘Ok’, and I worked it all out, no computers, and I said ‘if it’s a nice morning, a nice sunny morning, I think we’ll be OK’, and all the crew shouted ‘Go for it, Harry!’ so we did, and when we got to east Kirkby, it was a perfect morning , we went straight in to land and right at the end of the runway all the engines chopped. That took ten hours twenty five minutes, the longest op ever done in a Lancaster; we earned the record for that. So we had to go for briefing, and he was a bitch of a squadron leader, no, ‘well done lads you got back alive’, ‘who the bloody hell told you to come back here’, ‘who worked it out?’, ‘Harry’, he said ‘right mate, you are on a charge for causing probably damage to the air craft’, which it didn’t and damage to the men on board if it had crashed so I said ‘Oh’, he turned round to the crew and said ‘you’re not getting away with it neither’ he said ‘you are all on a bloody charge for being such stupid idiots’ just as he said that the group captain walked in, and he said ‘did I hear a plane landing?’ ‘cause [sic] nobody was supposed to be landing, so this squadron leader said ‘these bloody idiots here’ so he said ‘why, what, what you been doing lads?’ so we said ‘we’ve just got back from Munich via Italy’ and he said ‘really? and you got back safely?’, went round, shook our hands and the rear gunner said ‘we should be on seven days leave today’, he said ‘well done, go on leave’ and we never heard another word.

DE: Had the whole squadron done that route then?

HP: Yeah, so we were the only ones who landed back at East Kirkby

DE: Did you have to be extra careful with revs and working out wind speed?

HP: Oh yeah, yeah it was all interesting stuff, we had a lot to all make out but that was good. And then you finished your ops, it usually was thirty, but the crew had done thirty four, I’d done thirty-six so they said ‘right, you’ve finished, you can go on training other people now’ and the pilot was awarded the DFC for crew co-operation and the crew did not like that one bit, because we should’ve got something, we were doing the same job, but that’s how it worked, and then I was put back onto Stirling’s. When I got to this Stirling, I forget where it is, it’s all in my log back, when I got back to teaching on Stirling, I went to the pilot’s office, because you had to get a pilot who was trained in training pilots as well and he said ‘what’s your name and rank and everything?, what have you done?’, ‘well done’ shook me hand and he said ‘you’ve got two choices’, he said ‘we’ve got one pilot here that sticks rigidly to the rules, and we’ve got another one who’s come what may, happy go lucky’, so he said ‘who do you want to join?’, so I thought about it, I said ‘I’ll go with the happy go lucky’, he put his hand out and said ‘well done mate’, so I was with him, so we had to go and train a pilot and engineer on Stirling’s then, and it was getting near dusk, we’d done a few circuits but this pilot weren’t [sic] very good at all, so the pilot said to me ‘I think that this pilot is a bit jittery because I’m sat next to him’, so he said ‘I’m getting out, he says ‘you’re volunteering to stay in’ [laughs] I said ‘oh, thank you very much’ he said but ‘drum into him, the pilot, that if he’s got full flaps down, and the wheels down and locked, there is no way in this world he can overshoot’, well I knew all that so when I went up to the pilot, I said ‘you’ll be Ok but remember what we’ve just said’, so he said ‘OK’, we took off, we were just coming round the circuit, what happens, an engine goes, so feathered the engine and I said ‘not to worry, you can land just as easy on the three, no problem’, as I said that the flight engineer was rolling about on the floor shouting ‘I don’t want to die, I don’t want to die’, I thought ‘God’, whipped his mask off, so the rest of the crew didn’t hear the rest of what he was saying and I said ‘have you checked the wheels?’, ‘cause [sic] you had to check the electrics, so if it was a red light you’d have to give it a couple of turns that side, a couple of turns that side, say to the pilot ‘wheels down and locked’ and go right down to the rear wheel and do the same for that and shout out to the pilot ‘All OK, all wheels down and locked, go ahead and land’, then I heard a roar of the engines as I was walking up, he’d already told all the crew ‘brace, brace, brace’, because he’d decided to overshoot with the wheels down and locked and the flaps down so we crashed at Wigsley Woods?, do you know that, here?

DE: Vaguely, yes

HP: So I had momentarily been sort of knocked out and when I’d come to, I could feel we were on the ground and the plane had caught fire so I went to the door and jumped, I didn’t know if we were really in the air or not, but anyways the army were doing manoeuvres in Wigsley Woods and saw all what happened, came round, got us in their trucks, took us straight down to St. Georges Hospital in Lincoln, and I can remember being put on a stretcher ‘cause I couldn’t get up straight and seeing these bare entrance to St. Georges’ where the wind was blowing through ‘cause there was no windows or anything and going in to be examined, all the rest of the crew had just slight bruises, nothing really wrong with them, they thought I’d broke my back so they decided to lay me on boards and keep me that way for a few days, the whole time time I think I was in there was ten days. Then they put me in X-Ray and found I had just bruised my spine, not really done bad damage, so I was let out and another seven days survivor’s leave. I shall never forget that survivor’s leave, that second one because when I got to London, I was in civvies, got on the bus to Hackney, and a young woman got on the bus and I sat down and she looked at me and shouted ‘typical of these young scroungers not letting anybody have their seat’, so I got up and let her have the seat, I could have said something but I didn’t, but that was it. And then I had one of the pilots come up to me, and he, went back of course to do the training and one of the pilots come up to me and he said ‘it’s nearly the war’s over now’ he said ‘my engineers gone and disappeared, lack of moral fibre’ he said ‘so I don’t want to end up not being in the war, what would I tell my grandchildren if I got married and had any’ he said ‘would you fly with me?, on some more ops?’ I said ‘no fear, I’ve done mine’ so he pleaded with me, really pleaded so I said ‘OK then I’ll go with you’, so I went with him and ended up at Fiskerton and did three more bombing ops, the last one being Berchtesgaden, and, Hitler wasn’t there and on the way back is was, today like it is now, very clear, you couldn’t see any fighter pilots after you or anything so I got down ‘cause I was interested in H2S, do you know what that is?

DE: The ground radar?

HP: Yeah, you’ve got a screen and you can pick up things on the ground, and I was trying to teach myself how to do this and all of a sudden I thought something’s wrong and I looked round and the pilot had feathered one of the engines for no reason, the starboard outer and I knew there was nothing wrong, but I knew by sound that something had happened so I looked at the pilot and said ‘what the bloody hell are you doing, there’s nothing wrong with that engine?’ and he said ‘Ooo’ and he went like that and he feathered the second engine, so we were flying on two port engines and I said ‘you’re going bloody mad, you are’ and he was really mad because I was looking at the radar instead of looking at the engine, I said to him ‘I know by the sound, I’ve done so many bombing trips that I can tell by the sound if anything’s wrong’ so he said ‘oh bugger you’ and he went like that to unfeather but then he went and feathered the port engine so we were on one outer engine from twenty thousand feet we were down to seven, and I said ‘I think you’ve gone crazy’ I said, so he said ‘all right, you know it all you do it’ so I thought ‘what on earth can I do?’ so I said ‘OK, all the crew listen up’, I said ‘make sure you know where your parachutes are ‘cause we might have to bail out’, then I thought ‘what else can I do?’, switch of all your electrics, which I did ‘cause [sic] the port inner did the generator, so we couldn’t unfeather, so I was thinking to myself this is marvellous, you go through thirty nine ops and then this happens, what would they do if we crashed and found nothing was wrong, if we weren’t killed, we’d all end up in jail so I thought about it and thought ‘I know’, if you have a car and it’s a cold morning and you try to start it up and it don’t start you go ‘ooo ooo ooo ooo’ [makes sound as if trying to start a car] and in the end you run the battery down so you’re stuck but if you leave it for about five minutes just try it again it clicks over, so I said ‘right’ to the pilot ‘go into a slight dive’ he said ‘you bloody fool we’re at seven thousand feet already going into a dive’ I said ‘look you told me to get on with it so do what I’ve told you, go into a slight dive’ so he went into a slight dive and after a few minutes I thought right I’ll just try the port inner, try to unfeather the engine and it just started to tick round, not properly but going into the dive made the propellers go round and the engine started up, from that we got the generator working, I got all the other engines going and we never dared mention that to anybody till after, years after.

DE: I don’t blame you, how far away from home were you?

HP: Well we was [sic] halfway, we would’ve landed in Germany, and this Andrew Panton I told him about that as I was telling you and that’s when he said he was really interested.

DE: You’ve mentioned a couple of times other engineers that you took over from, who had gone LMF, can you tell me a little bit more about that?

HP: Yes, we never actually ever got finding these engineers at all [sic] but we did have a wireless operator who was similar to that, he disappeared, but they caught him, brought him back and that was terrible because we were all called out onto the square and this engine.., this wireless operator was put on like a trestle, stood there and the group captain called out that this man had disappeared, gone lack of moral fibre and I’m ordering him to have his stripes taken off, of course they were all loosened beforehand, and two squadron leaders came up, one on either side and ripped his strips completely off and then he wasn’t taken down, and I don’t know what really happened but I heard about a year later that he was put in the RAF regiment and went abroad on the ground, but it was terrible to see that happening, because, you could get frightened and scared and didn’t want to do it anymore and to have that done to you was terrible, but I think after the war ended they scraped doing that because it was too frightening, not only for the fella himself but also those people watching it being done, like watching someone being hanged.

DE: So you didn’t have any qualms taking over from that flight engineer who had gone missing then?

HP: Not really, [slight laugh] you could say that I was stupid, I were [sic] young and into it all, I did it all before I was twenty [pauses] when you see some of the lads today it makes you wonder.

DE: It does indeed yes, so was that the trip where you ended up on one engine for a while was that your last operation?

HP: Yes

DE: So what happened to you then?

HP: Well as I say, I met my wife on VE day which was a few days after that, so I decided I didn’t want to leave the air force, to keep into Lincolnshire but on actual VE day when it did come, I said to the crew, ‘I’m going into town because everybody will be celebrating’, and my second crew were all English and the rear gunner there said ‘I’ll come with you’, as we went along Monks Road there was so many pubs along there in those days that everybody was dragging us in, ‘have a pint with us, well done’, time we got into Lincoln we were just about kaylied and that’s when I stood at the Stonebow just thinking, I wondered what my Mum and Dad are doing in London, and there was two girls stood at the side, and an American officer came by and he said ‘we won the war for you’ and that annoyed me and there was a flag, you know these big streamers, one of the ends of it was hanging down as though it had fell down and I pulled it and the whole lot came down so I went up behind this American officer, I always had a pin in my lapel, I pulled this pin out and went behind him and pinned it on his uniform tail, because everybody was laughing at him and joking at him and he thought it was because he’d won the war for us [laughing] and one of these girls said to me ‘fancy doing that to our lovely Americans’, I said ‘well he deserved it, he didn’t win the war, it was all of us’ and I got talking to them and that’s when I met my wife, I said, I suppose it was about eleven o’clock then and they said ‘we’ve got to go now’ the two of them, so this particular one I said ‘can I walk you home’, she said ‘if you like’ [laughs] so I walked her home and that was funny because she lived on Grafton Street from Monks road, when we got to her door she said ‘Good night’ and she lifted the window up, I said ‘what’s the matter with the door?’, she said ‘we’re not supposed to be out’ [laughs] and they crawled in and I made a date to see her again and that was the start of us getting together, yeah, [pauses] that’s funny.

DE: So did you stay in the RAF then?

HP: Yes, first of all after VE day they decided that we were dropping food to the Dutch, I thought we were going to be civvies straight away but no we were on a mission to drop food to the Dutch, we did six of those and then I thought that’s it we’re off, then they said ‘no, you’re going out to Italy’ and I thought ‘what on earth are we going out to Italy for?’ but they didn’t say anything else and I said ‘ah well I’m going into’, it was VJ day then I think, ‘I’m going in to town, meet Mavis’ and again all these pubs, people were outside rejoicing, ‘come in and have a pint’, she worked in Lotus and Delta shoe shop at that time and when I got there, the manager was at the door, I said ‘is Mavis there?’ and he said ‘you’re drunk, bugger off’ [laughs], so I didn’t see her so I waited around for when the shop shut, I went there, walked her home, I had my bike, always had a bike with me, walked her home and her father came to the door and he said ‘you should be at camp’, I said ‘why the war is all over now’, I said ‘there’s no worries’, he said ‘you better ride on’ and as I say I was a bit drunk, and do you know the end of Monks Road going down to Fiskerton, it was a moonlight night, I got to the top on my bike I said to myself, ‘I’m gonna [sic] go down there and go round that bend, no hands [laughing] so I tried it, the next thing I remember was a big air men coming up to me, he says ‘excuse me sir’, ‘cause I was a warrant officer then, he said ‘did a van hit you or a car hit you?’ I said ‘no’, I said ‘I was biking down this hill’, I didn’t tell him I was going no hands [laughing], and ‘I must of fell off’ so he said ‘well where’s your bike?’ so I said ‘well it must be here somewhere’ and we looked all around and couldn’t see the bike at all, then I worked it out in my mind that what would have happened if I had going round, the bike would’ve gone that way and I went that way and it was over the hedge so picked it up and he said ‘where have you got to go back to?’ I said ‘ to Fiskerton’, he said ‘well I’m on that place’ he said ‘I’ll ride back with you and make sure you get there OK’ and he did, got me right to me hut and off he went and to this day I don’t know who he was or his name. When I got in, I had at the top end, the little room at the top and the crew were down the side, I got there and I just plonked myself on the bed, like that, just was nodding off and a navigator came in he said ‘where the hell have you been?’ he said ‘you know we are going to Italy’ I said ‘come off it, what are we going to Italy for?’ he said ‘well we’ve had briefing and we’ve been kitted out with KD equipment’, I said ‘What’s KD?’ well that’s khaki you know all the shorts and all that and I was still in me blue, and he said ‘we’re taking off in an hour’, so I said ‘you’re having me on’, he said ‘I’m not, ask the rest of the crew’, and they were all in the KD ready, so we went out to the aircraft, got in, on the way to Pomigliano. When we got there, we had to go, get off, and had briefing, and we went in for this briefing and the squadron leader spotted me straight away, he come up, ‘what the bloody hell you dressed like that for?’, I said ‘well I didn’t get a chance to go for my KD’, he says ‘you bloody fool’, he said ‘you’ll scorch’, so to get away from that I said ‘I’ve got an uncle in Italy’, he says ‘so what’, I said ‘well I’ll, I’d like to ring the nearest camp to here and see if he happens to be there’, he said ‘you bloody fool, there’s no phone’s here, there’s only the field telephone’ so I said ‘well, could I use that?’, so he had sympathy then and said ‘OK, I’ll let you have it by woe be told if you are having me on’ so he called the sergeant over and he said ‘get the field telephone and get through to which is the first camp nearest to us’, which actually was where we were bringing the troops back from, ‘so guard room’ so I picked the telephone up and said ‘is that the guard room?’ ‘Yes’, I said ‘you don’t happen to have a sergeant, quarter marshal sergeant or anybody of the name of Lenny Parkins?’, ‘speaking’, I said ‘what is that you Len’ he said why, who’s that?’ I said its ‘Harry, your nephew’; he said ‘where are ya?’ I said, I said, ‘I’m in Italy’, he said ‘why?’, I said ‘I’m in the RAF’, with that the squadron leader ripped the phone from me and said ‘if you are bloody having me on’ he said ‘is that right?’, he said ‘are you Len Parkins?’, he said ‘yes, I’m the Quarter Master Sargent Len parkins’ he said ‘I give up’ [laughing] and he put me back to me uncle and I briefly told him that how old I was and I was in the air force and he said ‘ I can’t believe it’ cause the last time he saw me, I was about that high, so he said ‘we’ll have to come and get you’ so I said ‘what do you mean?, ‘I better have a word with the squadron leader’, so I handed the squadron leader the phone ‘my uncle wants to have a word with you’ so it appeared that he wanted permission to come and pick me up and go and celebrate with him, VJ day the second this was, so the squadron leader said ‘OK, as long as you’re back here within three days’ so he said ‘that’ll be fine’, so that night, I forget what time it was but he came along with four of the biggest army blokes I had ever seen and all sergeants and he was in charge of them in this big van, and he looked at me and said ‘typical Parkins, what the bloody hell you dressed like that for?’, and I told him the story that I told you, so he said ‘you can’t go around like that’ he said ‘back to our store’ and he took me to the army store and I got kitted out with warrant officer in the army, so he said ‘right, we’re all kitted up now, we are going out, back to our camp’, which was the army camp, and he said ‘we’ve got a couple of things to do, we’ll sit you in the tent, then we’ll take you and we’ll celebrate’, so they did, and it was a place called Torre Annunziata where he took me, and it was like a little village with a big tavern, taverna there and there were some dancing girls, dancing round and that and me uncle sat down on a chair, there were chairs all around and there was a fairly elderly woman sat there and he could speak Italian by that time and he was chatting to her, and he said ‘what’s going on?’ and she said ‘they are picking out the best dancing girl and that’s my daughter there’ and he said ‘oh that’s interesting’ and he brought her a drink and it turned out that she was a famous film star later on in her life, can’t think of her name off hand, an Italian film star [pauses], no its gone out of my mind who she was, but we’d been introduced to her as a young girl dancer. And then the army bloke said ‘what do you want to drink, Harry?’ so I said ‘I’m used to black and tan now’, he said ‘you silly bugger, [laughs] you can’t get that out here, you’ll have to have something else, you’ll have to have a whiskey or gin or something like that’ I said ‘oh I can’t take that’ so one of them said ‘what about vermouth?’ well I had never heard of it, well I forget what you call it in English, it’s like a red wine so I said’ OK, I’ll have a pint of that’ [laughter] and they didn’t have glasses, where they had beer bottles they put a wire round it and tightened it very tight and then heated it and that broke off clean and then they just rubbed it on the stones to make it a bit smoother and that was filled up with this wine and when they said ‘cheers’ and we drinking it like beer and we ended up drunk as a newt with my uncle, sat on the fountain saying how we’ve found each other both alive. It was marvellous, so, I didn’t remember much after that but apparently they took me back to the army camp and there was a row of tents, right the way along with windows which were like strips of canvas down, and when I woke up in the morning, it must have been about ten o’clock the next day and I looked up and I saw what I thought were bars and I thought I was in prison [laughs] and I could hear talking outside, and there was two Italian prisoners of war, and actually they were sweeping up, but when I saw their sticks, it looked as though they had rifles and I thought I’m gonna [sic] be interrogated and you are always taught just give your name and number, don’t tell them anything else so I just sat there, I couldn’t see where my clothes were and I looked out and where they were sweeping, they went round the tent, so I thought right I’m escaping and I run like, stark naked, [laughs] I run like mad, right to the end of this, all these tents where there was a guard room and somebody came out and stopped me, with the rifles, took me inside and they started interrogating me, and I thought these are Germans disguised, ‘cause they tell you they used to do that and I wouldn’t say a word other than my name and number, word got round that they had captured either a spy or something but my uncle eventually heard about this, and of course he came chasing up to the guard room and saying all that had happened, so I got dressed [laughing]. And went, took me somewhere else to have a drink but I didn’t feel like having any drinks, and took me back to the camp, the RAF camp, and of course they looked at me being that in army with all my gear on, ‘how on earth had I changed into that’ and I had to explain that I was RAF and except that I had came out in my blue, and it was time then to pick up these soldiers and we used to pick up about twenty of them, and they had to sort of sit or lay all along the floor of the plane, and I’m always the last one in to check everything, I had to walk, actually walk on them, it was horrible really, and we did six of those and the last one, my uncle was one of the people coming back and he was getting married, when he got home and he said ‘where can I put all this stuff?’ and he’d got loads of stuff over the kit bag he was supposed to have, I think he had about five kit bags, gin, whiskey, rum, everything so I thought yeah why, let him have it all on the inside, outside of the aircraft in the bomb bay and I took some of it in with me, and didn’t say anything to the pilot. When we got back to Britain, the pilot said ‘I hope you lads didn’t bring anything back you’re not supposed to have because we might be inspected by the customs’ I thought ‘God, we’re gonna [sic] end up in jail’ but luckily, they just waved us on, and at the end my uncle had one of his army blokes in England, he’d got a truck and quickly loaded, loaded all this wedding stuff on this truck so we lucky again there but in between that, I had, I think it was the third time, we had the soldiers with the kit bags all loaded on, and an army officer came up to me and he said ‘who’s in charge of loading the aircraft?’ so I said ‘I am sir’ so he said ‘would you get all those kit bags off’, he said ‘over there is my yacht’ he said ‘ I’ve just taken all the measurements and it’ll just fit in there’, I said ‘you got to be joking’, he said ‘I’m not joking, warrant officer’ I said ‘well I’m not joking neither, no way is that yacht going on this aircraft’ and I said ‘none of those kit bags for the soldiers’, ‘cause they were all ordinary rank, ‘none of that is coming off’ so he said, ‘whose the pilot of this plane?’, so I rushed up to my pilot, quickly told him what was happening, so I said ‘he’s there’, so I took him up to the pilot and he said, ‘I’ve just had a word with your warrant officer and he’s refused to take my yacht with you’ so he said ‘well I’m afraid sir, he’s in charge, there’s nothing I can do’, so he came back to me and said ‘what’s your rank and number?’, he said ‘you are going to be on a charge when you get back to England and your feet won’t touch the ground, you’ll be out of the air force completely’, so I said ‘fair enough, do as you wish, I couldn’t care less’, well he was on our plane obviously so he said ‘I want the best seat on the plane as well’ so I said ‘ well there’s no seats on the plane’ I said ‘there’s the pilot, the navigator and the gunners, unless you want to be in the tail gunner?’ I said ‘I think he wouldn’t mind moving out’ he said ‘no fear, he said ‘I want a proper seat. Well the only other seat is the Elsan so I got all the soldiers on and put him on the Elsan, when we took off it, ‘cause it stunk like nobody’s business I said to the pilot ‘waggle the wings a bit’ and he did so it splashed all over him [laughs] I thought that’ll teach him, well I never heard anymore.

DE: Well that’s not where I’d choose to sit anyway.

HP: No, but there was another fella, he was Australian, he said ‘is there any chance that when you come into England you’ll go past the white cliffs of Dover?’ I said ‘yeah we go right over that, why?’, he said ‘well, I volunteered to help with the war, come to England’, he said ‘but on the way we got torpedoed and I ended up in a Japanese prisoner of war camp which’ he says ‘which was horrible’ he said ‘but that another mate and I managed to escape and we got to some English soldiers who took us into their camp and they said ‘well if you want to get to England we’ll have to take you to the docks somewhere and we’ll get you on the boat’ which they did and he said ‘and damn me and we got torpedoed again’ he said they ended up in the sea, fighting for my life and got picked up by life boats and eventually got to France and he said ‘and from there I managed to get to British air field where they were bringing back the troops and he said that was a trip to Italy and he said ‘here I am’ and I felt really sorry for him, I said ‘well when we come up to the cliffs of Dover, I’ll let you sit in my seat because I sit next to the pilot’ so when it was time, I called him up from where he was laying down and I said ‘there you are, there you can see the cliffs, the cliffs of Dover’ and he just cried his eyes out, really cried, to think that he eventually he’d got there and of course all the war was over, [pause] but that’s a few of the stories.

DE: That’s wonderful, thank you very much. So what did you do when you left the RAF?

HP: I didn’t know what to do exactly, so I looked in the Echo, ‘cause I was living with Mavis at her mum’s in Grafton Street, they always had the Echo and I saw a couple of adverts, one was for a sales man for Carabonham typewriters, not to sell the typewriters but to sell the carbon paper that they used to have, and that was an interview in town, the other interview was to, do you remember the chicken factory that used to be in Lincoln? Right down by the water side, a long walk right down, I got an interview for there and the other one was an interview, have you heard of Newnes? N, E, W, N, E, S publishers? Very famous publishers at the time, they were eventually taken over by the mirror group and then sold out again to some other big publishing company, I can’t remember their name off hand, so first of all I thought I’d go to the typewriter people, went to there and it was in an office just near where, I’ve forgotten what it was, near Marks and Spencer’s, up the stairs, went into there, there was about four or five other people there. Eventually I was called in, the man was sat at his desk and he said ‘put your hat on the coat hanger’, I said ‘I don’t wear a hat’ so he said ‘well if you work for us you have to wear a hat’ I said ‘oh’, I said ‘well I’ve worn a hat all this time in the air force, I don’t want to be wearing a hat again’ so he said ‘anyways give us a brief history’ which I did and he said ‘well if you wait outside we’ll let you know if you can come for a second interview and that’ll be the final interview’ so I said ‘OK’, well they interviewed the others and they all disappeared, there was only me there, so he came out and he said ‘yes, we’d like to have a further interview with you but we’d like to see you with a rain coat and a hat when you come next time so I said ‘oh,’ so I just said ‘oh and I walked away and ‘said I’d be there for the second interview’ well the next day was an interview with the chicken people, well walking down that long stretch of road, the stink of these chickens got worse and worse, I thought I could never work with that smell and I turned round and came back, so before this other interview, it was at Bradford for Newnes, the publishers, I thought well I’ll go back to this Carabonham people, went through and he said I notice you haven’t got an hat, I said ‘no, I haven’t got around to buying one and what is the exact position?’ he said ‘well you’ll be selling these carbon papers to various people that use typewriters, the pay will be seven pounds a week plus one percent commission and you make your own way around Lincolnshire, so I said ‘well thank you very much, I’m not interested, I earnt more than that in the RAF’ and walked out and when I got home my father in law was mad at me and my mother in law that I hadn’t got a job, well actually I had a month to go before I was officially finished with the RAF, so I said I’d go for this Bradford one and I hitch hiked, all the way to Bradford, got in for the interview and I saw a marvellous sales man who was the boss there and he said ‘what we want is a person who can sell publications that are in ten volumes, and it’s called pictorial knowledge’ he said ‘lots of people think its and encyclopaedia, it isn’t, its everything that an encyclopaedia could do but in pictures’, and he said ‘I got a specimen here which is what a sales man would use’, and he went through some of these pictures and what it did and what it said, and he said ‘contributors are Enid Blyton, have you heard of her?’ I said ‘oh yes I have heard of Enid Blyton, she’s famous’, there was, a fella who died not so long ago, Sir Edmond Hilary, he’s contributed to this and many other famous people and he said ‘there’s ten volumes to the set, and we would like a sales man who could go and sell these to parents to help their children with their education’, which sounded really good, so he said ‘would you be interested in that’ I said ‘yeah I think so, what is the wages?’, ‘well this is how we pay our people, for every set of encyclopaedias you sell’, not encyclopaedias, ‘pictorial knowledge’s you sell, ten volumes, we would give you a commission’, and I think it was about three pound fifteen, something like that, he said ‘most of our people, the minimum sales is about four a week’ so he says ‘that’s above the normal wage that you’d get if you went into a job’, so I thought well I’ve got a month of RAF pay still so I said ‘yes I’ll have a go’, that was it, so he issued me with a folder that opened out with the backs of ten volumes and also this small one where you showed all these pictures and what it did, right from five year olds to about fifteen year olds, so he said ‘there you are you are on your way, in Lincoln there’s a pub called the Saracens Head’, which was on the go then, he said ‘you’ll meet our supervisor whose name’s John’ whatever it was, he said ‘and he’ll take you out and give you a spin on what we do’, so I said ‘good’, he said ‘but before you go’, and he’d got a sheet of paper like that, with all names, of all occupations, he said ‘we sell these books, either by cash or by subscription, and subscription is a pound deposit and a pound a month’, so he said ‘that’s fairly easy for the average householder, but if they are in any of these occupations you can’t sell them other than cash only’, so I said looking down, I said ‘there’s no one left’, he said ‘you’ll find somebody’, so that was that, so I got home, hitch hiked again home, got home and told them what I was going to do and my father in law went [laughs] barmy.He said, ‘that’s not for you, commission only, I’ve never heard of such a thing, its extortionate’, mother in law was the same, Mavis didn’t say much at all, well I said ‘I’ve got a month to try it out’, so off I went, next day to meet this so called supervisor, I waited over an hour and a half, before someone came in with a briefcase, I thought, I wonder if this is him, I went up to him, I said ‘are you so and so with Newnes publishing?’ he said ‘yes’ he said ‘I’m bloody fed up with the job altogether’, he said ‘I’m leaving today so you are on your own’, I said ‘oh thanks very much’ and out he walked and that was it, so I had to figure out what to do, how to find where people lived with children because I didn’t want to be knocking on everyone’s door and gradually I worked out a system of getting names of people with children by going down a street, so if you can imagine that’s a street, people on that side, and people on that side, I’d go to the first one, knock on the door, go round the back door, often find it was an old dear who didn’t have any children, did she know of anybody along that way with children and I’d write it down, did she know the names, and possibly get four or five names which was good, then I’d say ‘I’ve lost my list so could you tell me the ones on the other side’ and often they could, a couple of doors along, then I’d go past those that I’d got, into the middle and do the same there, and then I figured out it was a bit daft going to the first house, this was after a while of doing it, that if I went to the middle house, I could get this way, that way, this way, and that way, and I ended up going round Sincil Bank, really poor sort of houses along there, and got a few names along there and that night I said ‘right I’m off out, see what I can do’, I knocked at the first house, got a spiel on how to get in and when I got in, I said ‘it’s in connection with Newnes the publishers’, ‘bloody encyclopaedia’s, bugger off’ and I got shut out the door, the next one wasn’t really interested at all, the third one, again three, always lucky to me, the fella said ‘come in, what’s it all about?’, and I told him and I went through the spiel that this manager had showed me and he said ‘yes we are very interested, we’ve only got one daughter and we’ll bring her out’ and I showed her this specimen for her to look through and she said ‘ooo Dad, can I have these?’ and she sold it for me, and they went in for the pound a month so that was good. Years later I saw this couple, in the town, I said ‘how did you get on?’ they said ‘the girl did wonderful, she’s at the high school, she’s getting on very well, all thanks to you’, it made me feel good, and anyways I did this and I thought where would be the most children, and that was off Boultham Park, can’t forget where that big housing estate, and I spent about two hours a day and ended up with about five hundred names of people with children and I did quite well, I started to getting four and five sets sold, doing well, and then Newnes got on to me and they said ‘if the people pay for three months that could never been counselled in your name but if they didn’t pay in the first three months, you’ve lost that sale and you’ve got to replace it, so I thought well how can I be confident that people were keeping up their payments, and I was in the Halifax at the time and the account in there and they were onto me about paying debits and credits and all that, but I didn’t know much about, but I got them to explain it to me and I said ‘what do you do?’ And they said ‘well you have a form and you fill it in and to pay whatever you want each month’, so I said ‘can I have a handful of those’ and they gave me a handful, so when I sold, I didn’t sell on the basis of a pound a month, I said to them ‘well you pay an initial deposit that gets you all ten books straight away so I’ll leave it to you, what would you like to pay as a deposit?’, some would say two pound, some would say what do you suggest?, I say ‘anything from five pound upwards’, so that got a lot of payments in and I said ‘do you happen to belong to the Halifax?, because if you do, save you trying to remember the date when you got to send off you can do it’ and I got them all signing up, so I didn’t get many bad payers at all, but you had to work your brain to figure out all these things and what to do, and then I was told that the manager of Lincoln branch was being promoted and going to a bigger branch which was in Leeds, near to Bradford area so they would be looking out for a manger for Nottingham, well I used to send all my stuff to Nottingham, so I went into Nottingham to see if I could have a word with the manager before he left but he’d already gone and the girl there said, well she was doing all the collecting payments, putting them down in the book and banking them and all that, so she said, ‘we’ve got some interviewees, that the other manager who’s gone should have been interviewing’, so I said ‘well I could interview them’, so I sat in the managers desk and I interviewed these people and I got a couple started and I got a note from head office to say, ‘we’re very pleased with what you did there, that was unexpected so we’ve promoted you to manager, a thousand a year plus expenses’, which was marvellous, so I used to have to go into Nottingham every day, and catch the train, ‘cause they used to have that train where it’s all the market place now, I used to chain me bike up to the gate, ‘cause I’d had an engine put on for when I used to go outside of Lincoln, I used to go to Boston on this little mini bike, Gainsborough, I used to do ever so well in Gainsborough, the big estate that that [sic] they built there, and one day when I was going round collecting names, a police car come up, came up to me and said ‘would you step over here sir’ so I stepped over there for him and he said ‘we’ve had complaints that you’re trying to get names of children’, and at the moment there was all this scare about children and weirdos, so he said ‘what exactly are you doing?’ so I explained it to him and I said ‘I’ve actually got me briefcase on me bike’ so he said ‘what do you mean?’, I said ‘well my briefcase has got me gear in when I go to these people to sell them Newnes’ pictorial knowledge’, so I said ‘do you live nearby?’ he said ‘why?’, I said ‘well have you got any children?’ he said, ‘yeah, two’, so I said, ‘well could I come and see you and I could explain exactly what I do?’ so he said ‘yeah that’s a good idea, and that’ll save you going into custody’, and he told me where he lived and after I finished doing a few more names, I thought I better not do many more so I went round to his house, he, he and his wife were there, went through the whole spiel, and I said ‘what do you think?, would you be interested?’, he said ‘yes I would’, he said ‘I reckon I could learn a lot out of those books’ so I signed him up, got his deposit and I said ‘you don’t happen to know any other people that might be interested?’ and he give me about a dozen names of people and everyone [emphasis] bought.

HP: Smashing yeah. And then another time I was going to Woodhall Spa, ‘cause I heard it was very rich people round there and I thought I could do some names round there then, so I got on me bike and chained it up, do you know that bridge which just before you get to,

DE: On the way into Woodhall? Yes.

HP: Chained my bike up there and walked in, and the first little housing estate I went in, well it wasn’t an estate it was a street, I went into a woman was giving me, me names and I never really told her what it was for, I just said it was to do with Enid Blyton, doing some research, so she said ‘come in, have a cup of tea’ she said ‘my husband’s a postman, he’ll be coming in shortly’ so I said ‘OK’ went in and had a cup of tea with her and she said ‘what really are you doing?’, then I said ‘well, I’ll be honest with you, seeing as you give me a cup of tea’ and I told her about it and she said ‘I think my husband will be all for this, could you come back at 5 o’clock?’ so I said ‘yes, that’ll be OK’ so I just went to, I think there was a little bar somewhere, where I could have a cup of tea, waited till quarter past five and went back and he was all for it, went straight into it, said he’ll pay a fiver deposit and he’d give me the names of everybody who he thought went to the same school as her and he said you should do well, and he gave me the names of those big houses where those driveways go down and I thought ‘God, I don’t know how I’m going to do here’. The first house I knocked on, a woman said ‘would you wait in the hallway, I’ll have to see the lady of the house’, so I said ‘why, who are you?’ she said ‘I’m the maid’ and I thought good God I’m trying to sell to people like that!

HP: She showed me into what she called the drawing room or the library, they got hundreds of books all around and I thought I’m not going to do any good here, and then the wife came out and said ‘what’s this all about?’, and I said ‘I understand you’ve got a young girl at such and such a school’ I said ‘I’m nothing to do with the school, I’m from Newnes publishers’ so she said ‘my husband will be interested in publishers’ so she said ‘I’ll go and get him’, he came in, sat down and I went through all the spiel and he said ‘that’s marvellous’ he said ‘I’ve called the daughter in and she can have a look at your specimen, if she’s interested we’re interested’, and it was a sale straight away, and I said there’s a method of paying which is on subscription where you can pay monthly or you can pay out right, and I think it was fifteen guineas if you paid outright, that’s fifteen pound, so he said ‘right, I’ll write you a cheque straight out for fifteen pound’, I said ‘well, I’m ever so sorry but Newnes wont except cheques, it would have to be cash or subscription’, he said ‘oh well’ and he went into a drawer, in the drawing room this was, pulled it out and there were stacks of twenty pound notes, piled it all out and that meant I had, fifteen pound, I had to give him some change, he said ‘you can keep the change’, [slight laugh] it were lovely. And every one of these houses that this fella had given me I got a sale, in one night I got seven sales from there, I was over the moon, I couldn’t go wrong at all.

DE: I think we better wind it up now; it’s been marvellous talking to you,

HP: I better say we had a son, a daughter and a son and then a little boy of six, well he had a virus that hit inside of his brain and he died, and it was terrible, Mavis’ never really been the same since, he would be about forty or so now, and it was hard for me to carry on doing this and in the end I said ‘I’d have to give it up’, and I gave it up and the next job I went for was Dymo tape writers, you know them?, they print out these tools, and it was with a director who was a manger of gothic electrical, have you ever hear of them?, well that was made into a home now, ‘cause that all, that faded away, and I was interviewed by this managing director and he said ‘yes we’ll very interested to you but you’ll have to wait for the Dymo manager came along ‘cause we would be doing it on behalf of Dymo through gothic’, so I said ‘OK’ he said ‘can you come back the next day?’ so I said ‘yes’ and this was in the afternoon, and I went in and when I explained what I’d been doing the Dymo bloke was over the moon, he said ‘yes we can take you on’, he said ‘it won’t be on any commission, it’ll, commission only, you’ll get a salary and you’ll get a commission but that would be up to the manager of Gothic’, he said ‘so I’ll leave you to him’ and off he went, so I said ‘well what is this salary and commission?’ he said ‘well the most we would pay you is seven pounds a week, I said ‘good God, I’ve been on more than twenty, twenty five, sometimes up to forty or fifty pound in a week’, he said ‘well I’m sorry but that’s the best we can do, he said ‘but we’ll give you one percent commission on all the machines that you sell, is that OK?’ I said ‘well I’ll say yes, and I’ll see how it goes because I’ve got to have a higher wage of some sort than that but if the commission brings me up then fair enough’.

Well when I went home they all wanted me to stay near home and it was only round the corner from Brant Road where we lived so I took the job on, so the first thing I did, was went all along every shop and business from outside of Bracebridge, right the way along that road into town explaining what Dymo was and I’d got an idea of getting a book with pictures on with different things that you could attach the Dymo label too, like electrical, you can put it on the meters, and put it on the switchboards and all sorts, so that was easy and another one was shoe shop where they could put it on the shoes and the price on the outside and then estate agents, it would look nice with a gold edge with gold lettering of the houses and the prices, that was dead easy selling them and I could also say to them and I could put your name as the manager on the door in gold letters which was really good and the first week I earned eighteen pound in commission so with my seven pounds,

DE: You were doing all right?

HP: Well the manager, the director of Gothic he nearly fell off his chair [laughs]. All on my own transport which was me little mini motor on the bike, well he said ‘I don’t know what to say’ he said ‘I can only pay you the wage this week and we’ll see how you go the next week’, and I thought ‘this sounds dodgy’, when I went in for my pay the next week, I had earnt nearly as much again, so he said ‘there’s your pay packet’ and I opened it up there and then and that just says seven pounds, he said ‘now I have to pay you your commission separate’ so I didn’t mind as long as he paid it, but that went on for a year, and I found with Dymo that if I went into place where they could sell the Dymo, I went to town for them to sell it with one that I’d sold myself I’d give it to them as their first sale and that went down really well because I’d got an order for not just one tool but several with the different types of tools they did, put in their shelves and that and so that went, went on really well until Dymo cottoned on to what I was doing because I was opening up shops to sell in Lincoln, in Gainsborough, in Spalding, which they could they get themselves so they took it over, and they took that away from me so all I could sell was to just ordinary shops not to sell for them to re-sell so that fell through and the manager director didn’t like that all and said ‘no we’ll have nothing more to do with it’ so as I say it all fell through and he said ‘we want a salesman because we’re losing one of our salesmen on electrical’ so I knew a bit about electrical but not all the intricate things that electrical dealt at a wholesaler so he said ‘and this would mean you probably could have a car’ so I said ‘when do I know about this?’, he said ‘well you’ll have to go to Birmingham and see the directors and owners there’, so I had to go there by train, got there and went before these directors and they were very interested in what I was doing in selling Dymo and also selling the books as well, they couldn’t get over that I could earn that amount of money so one of them said, ‘this is to do with selling Kenwood’ you know what Kenwood food,

DE: yes the Kenwood food processors and things?

HP: So I said ‘that sounds interesting, not to do with the electrical itself’ so they said ‘well in a way its electrical, we’ve just got the agency from Kenwood, so we’ve got full scale all around Lincolnshire’ so I said ‘well that sounds good’, so I said ‘well the main thing is I’ve got to earn a decent salary’ well my boss had offered me twelve pound a week from the seven so I didn’t tell them this and they didn’t know that from what I was talking to them about and they said ‘well initially we’ll give you twenty pound a week plus commission plus a car with all expenses’, so I was in.