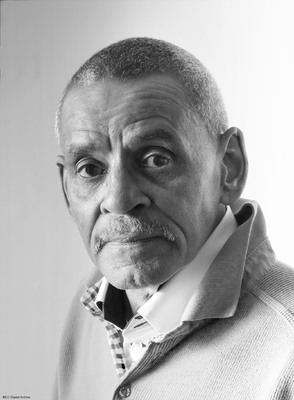

Interview with Neville Shenbanjo

Title

Interview with Neville Shenbanjo

Description

Neville was born in Leeds in 1945, one of seven children of Akin Shenbanjo DFC, who served as a wireless operator with 76 Squadron.

The first part of the interview relates to Neville's early life and relationship with his father. Neville was brought up by his grandparents as his father had separated from his mother, who had been a parachute packer, and his father was away in the RAF.

Akin was stationed near London where he remarried and Neville visited him but always returned to his grandparents as he was homesick. He recalls that Akin's visits to Leeds were always special as he arrived resplendent in his officer's uniform. Although the visits were infrequent, they kept in touch by letter.

Akin was born in Nigeria and wanted to join the RAF but was told that he had to travel to England and enlist there. As the oldest child he was entitled to money to see him through university, which he used to pay for his travel to England, causing him to lose status in the family and made his return to Nigeria difficut.

After training, Akin was posted to RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor where he crewed up after meeting his pilot, with whom he remained firm friends for the remainder of his life. Their aircraft was named "Achtung the Black Prince" in honour of Akin's ancestry.

Akin's flying career seemed uneventful except for having to bale out of a Lancaster whilst on a test flight when the rudder became jammed, causing the aircraft to fly in circles over the sea off the Lincolnshire coast. Landing in a churchyard, he was confronted by a shotgun armed woman who refused to believe he was in the RAF, until rescued by the local police.

After cessation of hostilities, he was posted to Palestine where he narrowly escaped death. Having a sing-song around a piano, his secretary asked him to take her out to a local pub. Having left the room, the piano exploded with devastating results. It was felt that the secretary was aware of the bomb and had saved Akin because he had taken some letters to Leeds for her.

Akin flew in the RAF as a volunteer until 1951 and with the aid of Yorkshire TV he found his old crew members, five of which were still alive. He continued to return to RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor for reunions until the numbers diminished and 76 Squadron association was disbanded, although the next generation still keep in touch via the internet. Akin visited Germany and felt very sad at the destruction.

After the RAF, Akin became a chartered surveyor and worked for the Post Office. Sadly he lost his sight in later years and died at the age of ninety years.

The first part of the interview relates to Neville's early life and relationship with his father. Neville was brought up by his grandparents as his father had separated from his mother, who had been a parachute packer, and his father was away in the RAF.

Akin was stationed near London where he remarried and Neville visited him but always returned to his grandparents as he was homesick. He recalls that Akin's visits to Leeds were always special as he arrived resplendent in his officer's uniform. Although the visits were infrequent, they kept in touch by letter.

Akin was born in Nigeria and wanted to join the RAF but was told that he had to travel to England and enlist there. As the oldest child he was entitled to money to see him through university, which he used to pay for his travel to England, causing him to lose status in the family and made his return to Nigeria difficut.

After training, Akin was posted to RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor where he crewed up after meeting his pilot, with whom he remained firm friends for the remainder of his life. Their aircraft was named "Achtung the Black Prince" in honour of Akin's ancestry.

Akin's flying career seemed uneventful except for having to bale out of a Lancaster whilst on a test flight when the rudder became jammed, causing the aircraft to fly in circles over the sea off the Lincolnshire coast. Landing in a churchyard, he was confronted by a shotgun armed woman who refused to believe he was in the RAF, until rescued by the local police.

After cessation of hostilities, he was posted to Palestine where he narrowly escaped death. Having a sing-song around a piano, his secretary asked him to take her out to a local pub. Having left the room, the piano exploded with devastating results. It was felt that the secretary was aware of the bomb and had saved Akin because he had taken some letters to Leeds for her.

Akin flew in the RAF as a volunteer until 1951 and with the aid of Yorkshire TV he found his old crew members, five of which were still alive. He continued to return to RAF Holme-on-Spalding Moor for reunions until the numbers diminished and 76 Squadron association was disbanded, although the next generation still keep in touch via the internet. Akin visited Germany and felt very sad at the destruction.

After the RAF, Akin became a chartered surveyor and worked for the Post Office. Sadly he lost his sight in later years and died at the age of ninety years.

Creator

Date

2017-07-27

Language

Type

Format

00:54:36 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AShenbanjoN170727, PShenbanjoA1701

Transcription

HH: Neville, it’s lovely to be with you here this morning. Just for the record at the start of this interview let me say that I’m Heather Hughes and I’m here in Neville Shenbanjo’s flat in Leeds and it is Thursday the 27th of July 2017. And it’s lovely also to have Keeley here with us who is going to hear some of her dad’s stories about the family. Thank you so much for agreeing to, to be interviewed for our project.

NS: No problem.

HH: It’s been wonderful to meet you. Let’s start by talking a little bit about you and then we’ll get on to all the wonderful stories that you have collected, that you heard from your dad and that you are hopefully going to pass on to the rest of your family and a lots of other people besides. So I wonder if we could talk about you first Neville and where you were born and when.

NS: I was born on the 22nd of February 1945. I was born at number 22 Crawford Street, Leeds 2. Childhood was extreme. I can remember my childhood. I can remember being a baby. We was brought by my grandmother and grandfather. We lived with my grandmother and grandfather and it was wonderful. My father was away. I were born in ’45 but my father was still an officer in the Air Force and I think at that time he was in Palestine but he used to come home regular on leave. And it was really surprising because most children at that time had somebody in the armed forces, somebody in the family but when my father came home they used to love it because he was in an officer’s uniform and that felt really special, you know. For me, a little boy that felt really good. My mother and father split up when I was around about three, four years old and I stayed, I stayed with my grandparents. We moved to Seacroft when I was around about five years old. Moved to Seacroft in Leeds when I was about five years old and that was, that was a change because we moved out of the inner city to open fields but it was wonderful. It was absolutely marvellous and there were times when I thought things aren’t right you know because I was with my grandmother and grandfather. My mother used to live around the corner but I was happy living with my grandmother and grandfather. My father still came and visited. And then again in his officer’s uniform and all this. Kids used to come out in the street. Anyway, my father moved back then. He moved to London and I didn’t see him for quite a while. He used to write. I didn’t see him for quite a while. I think the last time I saw him when I was around about nine. He came up visiting. When I was twelve he asked me to go to London to visit him. I can remember my grandmother and grandfather putting me on a train to London. Twelve years old. I thought how exciting this is. Went to London. Stayed with my father but oddly enough after a week I was homesick [laughs] I missed, I missed my grandparents so I came home. But I used to go and visit regular. I had a friend who lived around the corner and his grandmother, he’d come and visit his grandmother but he came from Twickenham. I’ll never forget him. Tom Courtenay, they called him and I’m still in touch with him now and he came from Twickenham and he used to, he used to stay at his grandmother’s during the school holidays and I used to go and visit him. And then we used to go and visit my father. Now, I never saw my father again. I would write him but we lost all contact and I thought what’s happened? And I was eighteen and I had a letter from my father saying, ‘I’m remarrying. Would you come down and visit me?’ So I did. And he remarried again and I thought marvellous. He’s happy. He had another boy. That was good and I kept on visiting. But it wasn’t right, you know. I didn’t feel comfortable in his house with this strange woman. I don’t know why. I don’t know why I didn’t get on with her but there was something about her. But anyway, everything turned out okay. Now, about my father’s stories —

HH: Before we go onto your father’s stories how, just tell me a little bit about how, how your mum because you said she had been a WAAF?

NS: My mum was a WAAF, yeah.

HH: So tell us a little bit about your mum.

NS: My mum, she always said she couldn’t wait to be eighteen so she could join up. She always wanted to join up and she liked, well she wanted to join the Wrens because she liked the uniform better [laughs] but she joined the RAF. Now, she used to pack the parachutes and hand the parachutes out and that’s how she met my father because James Watt who was my father’s pilot who, Jimmy Watt but his real name was Reginald but he liked to be called Jimmy and he was going to, she told me this story that they were going to get their parachute and they have to give their name. So, she says, ‘Name?’ So Jimmy says, ‘Watt.’ So she says, ‘Name?’ So he says, ‘Watt.’ So she says, ‘What is your name?’ So he says he had to get his card and say, ‘Look, that is my name.’ And that, my father was behind and that’s how she met, that’s how she met my father, you know. So it’s just a funny story like that.

HH: And what happened to your mum after the war? What did she do?

NS: My mother. She, well, well she was pregnant during the war.

HH: Yeah.

NS: And so she was asked to leave. You had to leave the Air Force.

HH: Yeah. They had to didn’t they? Yeah.

NS: So, she left the Air Force and just carried on with life, you know. Well, left the Air Force, got married. They got married at Leeds Registry Office. They were supposed to get married in a church. I shouldn’t tell you this. They were supposed to get married in a church but my dad kept, there were going to be press there and my father didn’t want any press to be there and he changed, he changed it twice and they finally got married in Leeds Registry Office. Just so that there weren’t any press around. That’s how my father was. And my mother remarried. I’ve got six, six siblings on my mother’s side and they all live close as well.

HH: And you stay in touch with most of them?

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah. I’m going on holiday with them next month. With one of my sisters. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Carole. Yeah. They’ve all got families of their own now. Well, everybody has, you know. Grandparents and grandchildren. Yeah. We get on really great. All of them.

HH: Great.

NS: Yeah.

HH: So, let’s talk a little bit then I want to, I want to come back to the the way in which you have remembered your dad and the little, the shrine that you’ve created to your dad here. But I think, let’s go back and look at some, look at your dad’s time in the RAF and tell me how he came to be in Britain because he was Nigerian wasn’t he?

NS: My father was Nigerian. Yeah. He had two pals in Nigeria. They called them the [Coss], the [Coss] brothers —

HH: And you’ve got a picture there of them.

NS: [Aberwello], yeah. [Aberwella Ollawalli], Akin Shenbanjo and Adie [Campbell]. Not a very Nigerian name that Adie Campbell but only two arrived. My father and [Olliwello].

HH: Now, your father had tried to enlist in Nigeria and he was told that —

NS: Well, he didn’t try to enlist in Nigeria. He wrote to the War Office.

HH: Oh okay.

NS: He wrote to the War Office asking to join the RAF but I think this was 1941. The Battle of Britain. Everybody wanted to be a fighter pilot but the office, the War Office wrote back to him and said, “We aren’t recruiting from Nigeria at the moment.” So that’s it. My father wrote back insisting, ‘but I want to join.’ So, the War Office wrote back and said if you want to join you can make your way over to England and just go to the nearest recruiting office and join. You can take this letter with you and join. So my father had a scholarship to go to university. So he used the money that his father gave him to come over to England. That’s why my father could not go back. He was the oldest child. So he could never go back. He give, he give his right up and he’s never been back to Nigeria. He never went back to Nigeria. They came over. They got the boat. They got to the Recruiting Office at Southampton, they both went in to the Recruiting Office and said, ‘We’ve come to join the RAF.’ And they had, I don’t know whether he said they laughed at him but they just said, ‘Well, you can’t.’ But my father pulled this envelope out and said, ‘Oh.’ So the man said, ‘Well, alright. You’re in the RAF.’ That was it. Then they both joined together and my father’s friend during training he discovered he was scared of flying and so he had to go on ground crew. My father lost touch with him and that was that. My father was, I don’t know how he finished up at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. But that’s where he was and that’s where he met his pilot. Now, I was talking to Jimmy Watt. I said, ‘How did you meet my father?’ So, he said, ‘Well, I was walking around. I was walking around the base and I saw your dad sat on this wall so I approached him. I went over to him. I said, ‘Look, I can see all your ribbons,’ you know wireless operator, navigator. He said, ‘Have you not done all this training?’ So my father replied, ‘I’ve done so much training I could fight this war on my own.’ Well, Jimmy said to him, ‘Right, come with me,’ and that was it. They were settled from that moment on and I’m still in touch with Jimmy’s son. We phone regularly. Once a fortnight we’ll phone. There was a time, it was around about six years ago. I had a phone call to say that they was disbanding 76 Squadron. Well, it was only I used to go visit Spalding Moor. I used to go to all the reunions and everything. In fact, the school, a primary school there and the 76 Squadron has done so much for that school the children absolutely love it and they know all about the war and all that 76 Squadron did because they are teaching children about the war now. They never taught them about the war when I was a kid. We never got taught about the war. In fact, my grand, my grandson, Keeley’s son there was, they asked if there was anybody had got any grandparents, any old pictures? So I sent the pictures and my dad’s medals. They were flabbergasted. They were over the moon with that. Yeah. Anyway, go back to where were we?

HH: We were talking about your dad having got together with the pilot Jimmy Watt.

NS: Oh, he got, yeah he got together with pilot, Jimmy Watt.

HH: They flew in 76 Squadron obviously and they flew Halifaxes.

NS: They flew Halifaxes. Halifax. They named my father’s Halifax, “The Black Prince.” They didn’t like naming the planes at that time because they said, ‘Don’t name a plane because if a fighter gets the name of that plane or it shoots down something they’ll come looking for you.’ So my father said, ‘As long as I’m flying this plane nothing will happen.’ And nothing ever did. Now, my father flew so many missions because it was practically every night there was somebody goes ill or something like. Most like they just get scared. You think, this is it. It’s our time. And they don’t refuse to fly but my father would always volunteer to go. My father flew in most planes at that base. He told me about it because they thought, nobody would pick my father as crew, they thought he might be bad luck. I don’t know why. But when Jimmy Watt picked him up everybody thought he was good luck and so they were getting him to fly. I don’t know how my father got his DFC. I’ve never found out. He never told me and I’d like to find out how my father was awarded the DFC.

HH: It would be possible to find out.

NS: Yeah.

HH: We can do something about that.

NS: I’d like to find that out. Yeah. Yeah. Well, I can’t think now. I’m stuck.

HH: No. Not at all. So [pause] your dad would have flown with quite international crews because —

NS: Yes.

HH: There were Canadians —

NS: Yes. My father was, well the pilot was Canadian. Two Australians. A New Zealander. Two Australians, two New Zealanders and an Englishman. That was it. Nigerian.

HH: A really international crew.

NS: Nigerian, two New Zealanders, two Australians and an Englishman. That was it. Yeah.

HH: And they became like family didn’t they?

NS: Oh, well they all were family because they never, they were always together. You know, they all used to eat together and do everything together.

HH: Well, they had to look after each other.

NS: They had to look after each other.

HH: To come home safely I would think.

NS: They had to look after, they had to look after each other and they never made friends, never made close friends with any other, any other bombers because they were losing too many friends. They said they used to go in to the mess hall for breakfast on a morning there used to be two tables empty. You know. So —

HH: And did your dad’s entire crew survive the war?

NS: All of them survived the war.

HH: Remarkable.

NS: They all survived the war.

HH: That’s remarkable.

NS: They all survived the war. The plane was never, I heard a story when they finally had to leave the plane and the plane went up again it never came back. You know. So, and that’s, that’s supposed to be a true story. Yeah.

HH: And what happened to your dad after the war? Did he stay in the RAF for a while?

NS: He was in the RAF until 1953.

HH: Gosh.

NS: ’53 or ‘54 because I know he was, he told me this story and I shouldn’t really say this but I’ll tell you the story anyway. It’s coming out now. He was in where did I say he was? Not Israel. Palestine.

HH: Ah huh.

NS: He was in Palestine and he had this secretary. Now, she had relations in Leeds and she knew that my father came from Leeds and she asked him if she could send him some letters but my father, he read the letters first because he wasn’t allowed to send them, but he did post them for her. One day he was in the mess hall. He said, ‘We were just having a sing song round a piano and this secretary banged on the window and he said, ‘What do you want?’ ‘Will you come out with us for a drink?’ So he said, ‘I’m with my pal here.’ They said, ‘Well, bring him us. We’ll go out for a drink.’ And they left the base and they got a hundred yards down the road when the mess hall blew up. There was a bomb in the piano. Now, this, she must have known about it but she got my father out and I don’t, I know you shouldn’t of have wrote, read those letters.

HH: Don’t worry.

NS: But if he hadn’t have done he might have gone up in that.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Anyway, that’s another story.

HH: He was clearly a very lucky person.

NS: He was. Yeah. And a well liked person. It’s amazing. People have met him and they said, ‘Your father’s amazing.’ And I said, ‘Well why? He’s just a normal man.’ ‘No. He’s amazing.’ Even my friends you know, ‘Oh, your father’s so different.’ I said, ‘What do you mean so different? He’s just like your father.’ He said, ‘No. there’s something about him.’

HH: What do you think it was that people saw?

NS: I don’t know. I don’t know. But my grandparents. They loved him. I mean imagine 1945. Your daughter comes home with a black man.

HH: There was a lot more prejudice then then there is now yeah.

NS: Oh yeah. No. Well, no but my grandfather had seen my father. He used to be a boxer in the RAF and he’d seen him boxing.

HH: So was your dad a boxer as well?

NS: Yeah. Yeah. He was lightweight boxing. I think it was from all the Army, Navy and Air Force champion. Yeah. Yeah. And my father had seen him box you see. My grandfather. He must have boxed at Leeds Town Hall or something like that. That’s anyway they really liked my father. My grandparents.

HH: How do you remember your father? What was he like as a person? What was his personality like?

NS: It’s hard to say by me because he was strict but he wasn’t strict with me. Probably because we were distant or I don’t know. The distance between us in part but he was very strict but he was very moral. I know that. But he was very fair as well. A marvellous man. A really marvellous man.

HH: Did he ever wish, did he ever voice a wish to return to Nigeria or was he quite happy to stay here after the war?

NS: He was happy to stay here. He’d never been back to Nigeria. His son and his second wife they went to Nigeria. But my father never went.

HH: Did he maintain contact with his family there?

NS: Yes. Now, he had a sister. She was a nurse and I can remember her coming to visit us when we were living in, I was only four years old. Grace, they called her. I named that statue after her. Auntie Grace. She was marvellous. She was a nurse and she used to come to England. She used to go to St James’s Teaching Hospital. That’s in Leeds. And she used to learn things there and then go back. She used to come regular. And he had a brother who used to come over and he brought me my first pair of football boots. I never get it in London. You go out of Woolworths in London. I’ll never forget that. Yeah. Marvellous man. And he’s got there are so many Shenbanjo’s in England now it’s unbelievable.

HH: Oh, really. Well, there you are.

NS: If you go on Facebook —

HH: Okay.

NS: You find so many Shenbanjo’s and America, Australia. There are Shenbanjo’s all over the world now. Yeah.

HH: All over. Yeah.

NS: Yeah. You know, so he spread the word my father did.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Yes.

HH: So, but you it was after the war when, when you presumably, you know you’d finished school and you were becoming an adult. You, you, did you, you helped your dad quite a lot to stay in touch with squadron and so on and Squadron Associations —

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: And so on. Tell us about that.

NS: Well, I was, I used to go and visit. I worked in Peterborough and I used to go visit my father because London, Peterborough an hour’s drive. I would drive. So, he’d be North London. Kingsbury. So just an hour’s drive down the A1. One day I was there and my father said to me, ‘I want you to do something for me son.’ So I said, ‘Yeah. Whatever you want dad. I’ll do it.’ He said, ‘I want you to get the crew together that I flew with during the war.’ So, I said, ‘Okay dad.’ Just said it like that. I went out. I got in to the car and I’m driving up the A1 and all of a sudden I was thinking how can I do this? And I thought fifty years from now. That’s what he’s talking about. That’s what they said, ‘We’ll meet fifty years from now.’ I drove up the A1, got back to Peterborough. The next day I’ve come up to Leeds. I’ve called at my mother’s because my mother was a WAAF at 76 Squadron. And I said to her, ‘Look, he's asked me to do something.’ She said, ‘What?’ ‘He’s asked me to get the crew together he flew with during the war.’ Well, my mother looked at me stupid and she said, ‘Well, there was Jimmy Watt. He was a Canadian.’ I thought, ‘Well, I know that mum.’ She said, ‘But there was something on the television last night. It was about bombers flying from Holme-on -Spalding Moor.’ So the next day I went down to the studios, Leeds Studios. Television studios. I went to the reception desk and I told the receptionist what I was looking for. She said, ‘Look, I don’t think I can help you but just hang on.’ She went upstairs and she brought down the producer with her. Well, this producer said, ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I, I aren’t supposed to do this but I’m going to give you this video and you can watch it and if you find anything that’s okay but you must bring it back.’ So I said, ‘No problem. I’ll bring it back.’ I took the video, I watched it I couldn’t see anything on it. So I went back to this television studio the next week and I went to see the man. Look,’ I said, ‘I’m sorry. Thank you but I couldn’t find anything.’ So he said, ‘I want you to ring this number.’ He said, ‘It’s a lady. Patricia —' I’ve forgotten her second name.

HH: Was it Welbourne or something?

NS: Welbourne.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Patricia Welbourne. They used to call her Paddy. So I said what? ‘Oh, she used to work.’ She used to be, she was there and she was something to do with 76 Squadron. So I rang this lady in York and I said, ‘Mrs Welbourne?’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ Oh, I said, ‘You won’t know me. My name is Neville Shenbanjo.’ Well, she said, ‘I haven’t heard your voice in forty eight years.’ And I was, I said, ‘No. No, that’s my father. That’s my father.’ She said, ‘We’ve been looking for your father,’ you know, to get [pause] Anyway, that’s when it all started. She gave me the number of Jimmy Watt and I rang Jimmy Watt up in Canada. And that’s when it all started. I got three of them together. And I think five, five of them we all met once at one reunion. One guy had died and he’d lived just near my father. We got the rest together and marvellous. I’ve met Jimmy Watt three or four times.

HH: So you, so you made your dad’s wish come true.

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah. Yeah. He was over the moon about that. Yeah.

HH: Was he, was he really thrilled?

NS: Oh well, when he met Jimmy Watt after those years, there’s a picture on the wall there. Arms around each other.

HH: And where was that reunion? Was it —

NS: It was at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. At the —

HH: Okay.

NS: At the base. We, they still have reunions there but there’s not many people to go now.

HH: No.

NS: You know so it’s —

HH: But what, what about the next generation like you?

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: Do they still participate?

NS: They still go but it’s done mostly like everything else internet now and over the phone. You know. That’s how, that’s how, that’s how they communicate. But I haven’t been there for a while but I still like to go back every, what am I going to do this Sunday? I’m going to go visit there. There’s a funny story. We was there one day and I don’t know whether this is true or not but there one day there must have been thirty of us all there and this guy came. The place is an industrial estate now and this guy came up to, up to the crew and he says, he were the head of the security and he said, ‘I’ve got to tell you guys something.’ They said, ‘What?’ He said, well he was, one of his men was just going around the perimeter and security and he said he saw these kids playing football. So he thought that’s odd because it’s in the middle of nowhere this place. So the security man went up and there were kids playing football and he said they all had uniforms on. He said they had RAF uniforms on he said. And that man, he just ran back to the office and he said, ‘I’m not going back there.’ So they said it was the ghost of the —

HH: Yeah.

NS: But I didn’t believe it but the man never went back to work.

HH: He was convinced.

NS: He never went back to work.

HH: Yeah.

NS: So, I’ll tell you stories about my father then. What did he do? You know, it’s hard to say. It’s hard to —

HH: What did he do when he came out of the RAF?

NS: He, he went to work at the Post Office. Then he finished up as a chartered surveyor. I don’t know. I know he worked at the Post Office for a while and he went as a chartered surveyor.

HH: And all the time he was living in London was he?

NS: All the time he was living in London. Yeah. All the time he lived in London because I can remember when I was a kid my father used to send money up for me because my mum and father was divorced. And now and then this money didn’t arrive. My mother used to get angry about it. Anyway, the sad thing is we had a guy that lived around the corner and he was our postman and he was stealing the money.

HH: So your dad was sending the money.

NS: He was sending money but this post, anyway this postman finished up in jail for it. Then my father was forgiven for that. Yeah.

HH: How did you discover —

NS: Well, my father said, my father worked at the Post Office and he was sending it up registered. So, they just had to, I think they just —

HH: Yeah.

NS: They tricked this guy.

HH: Yeah. And sadly he went blind in his later years.

NS: My father went blind in his later years, yeah.

HH: And when did he pass away?

NS: Twenty five, twenty five years ago, I think.

HH: Gosh.

NS: Twenty five years.

HH: So it was in the ninety, late 1990s.

NS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, that’s when he passed away.

HH: And where is he buried?

NS: He’s, he was cremated.

HH: He was cremated.

NS: And it’s, and it’s, there was a plaque on the wall. It said, oh it’s in a crematorium in North London. I can’t remember.

HH: Okay. So, it’s in North London.

NS: It’s in North London.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Not far from Kingsbury.

HH: Okay.

NS: So, the crematorium there.

HH: And you were just telling me earlier that your mum survived a very long time and only passed away quite recently.

NS: Yeah. She was ninety one, my mother. Yeah. She’s passed.

HH: And she’d always lived, continued living in Leeds.

NS: Continued living in Leeds, yeah. She lived just up the road.

HH: And how come you found your way back to Leeds after you’d been in Peterborough? Where else did you travel and work?

NS: Well, I just happened to work in Peterborough. I just wanted a job and I’ve been an optical technician all my life. Since I was fifteen. And they were asking for somebody in Peterborough. So I went. I used to travel back to Leeds every weekend you know.

HH: So your home has always been in Leeds.

NS: My home has always, I’ve always had a home in Leeds. Yeah. Yeah.

HH: One of the things I wanted to, to ask you was how you, I mean obviously you have a very personal interest in how Bomber Command, RAF Bomber Command is remembered today. Do you think that, that Bomber Command is remembered adequately? Do you think that they’ve been given the respect or the recognition they deserve?

NS: They are now. At one time they was not. Not at all. My father regretted. My father made a lot of German friends. He used to visit Germany a lot. He liked Germany. He felt so guilty, you know. I remember my father bombed Dresden and places like this and after the war he used to feel, he felt so sad you know. He told me this. But what could he do? He had to do it and that were, that was the end of it. I was very proud of him naturally. And everybody else is. I had friends and they say to me, ‘Oh, your father. Oh yeah, he was an officer.’ And some still don’t believe me and I’d say, ‘Yes, he was an officer in the RAF.’ I can remember some guy once said to me, ‘No black men flew in the RAF.’ And this guy was in, this guy had been in the RAF, you know [laughs] I just laughed.

HH: Because I think, I mean don’t you think that that is an issue? That Bomber Command, you said earlier you know they didn’t have recognition for a long time but within, within that lack of recognition the, the black airmen and, and others who served in Bomber Command got even less recognition.

NS: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Probably. Probably. But I can’t see it though because my father was made an officer. So no. I don’t, I don’t think there was any prejudice in.

HH: No. But afterwards. The way in which Bomber Command has been remembered afterwards.

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, it’s sad because nobody realises. All they think about is bombing children and things like this. Nobody understands that it had to be done. It was something that just had to be done and that was the end of it. You know, I understood. I understood this for a long time. Yeah. When they say about [pause] some of the things he did he told me and I just, everything just gone out of my head. Ah. I made some notes. [pause] In training. Him and Jimmy Watt. There was one time I was in Peterborough and I was in the pub and somebody came around, they put, ‘Anybody want to do a parachute jump.’ Well, you know it happens doesn’t it, in a pub? No. I was over forty then so I said, ‘No way.’ And I think I was forty. Anyway, they came back an hour later. That would be another three pints later [laughs] and the hand was up straight away. ‘Yeah. I’ll do it.’ So, then I thought, ‘What can I do now? How do I get out of it?’ So, I was going to visit my father the next day. So I went to my father and I said, ‘Dad, I’ve done something stupid.’ He said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘I volunteered to do a parachute jump.’ He says, ‘You’ll love it.’ I said, ‘Dad, you never did one.’ He said, ‘I did.’ I said, ‘Why? Your plane was never shot down.’ He said, ‘We were test, test flying a Lancaster over the Humber Estuary and the rudder got stuck so it was just going around in a big circle all around the Humber Estuary. Well, we had to get in touch with base and they had to get in touch with Bomber Command and the only thing to do was bale out and, ‘Bale out while it’s over land and then we’ll send some fighters to shoot it down.’ That’s the only thing they could do. So they all baled out. My father landed in this church yard in [pause] Oh where? Anyway, in this village churchyard. I remember the name of the village. And he said, ‘I landed.’ Well, they had overalls over their uniforms then. He said, ‘I landed in this churchyard and this vicar’s wife came out with a shotgun. And she had a shotgun over me.’ So he said, ‘Look, I’m British.’ So she looked at me and said, ‘Oh no you’re not.’ [laughs] Anyway, then the vicar came out and the local, local police sergeant. They let my dad, and then they realised. Well, the policeman did anyway. They realised he was British. And that woman used to send my father Christmas cards and birthday cards for twenty years before she died. That’s how, that’s how friendly he was. That’s how people took to my father. You know, it was just like that.

HH: That’s a wonderful story.

NS: Anyway, I did the parachute jump [laughs]

HH: And how did you find it?

NS: Marvellous. I wanted to do another one. I’d do one tomorrow. Yeah.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Yeah. That’s a good story about my dad. [unclear] Parachute. Oh, and Jimmy. Jimmy Watt, I were talking to him and he said, ‘You know once,’ he said, ‘We had, we couldn’t land at our base. There was something up with the plane. We had to land at this other base.’ And there there was American bomber planes. Well, they landed. ‘They took us in to the mess and this one crew member said to Jimmy Watt, he said, ‘Does he fly with you?’ So, he said, ‘Yeah.’ So he said, ‘Well, aren’t you segregated?’ He said, ‘What do you mean segregated?’ so he said, he said, ‘We fly together, we eat together and,’ he said, ‘We’ll probably die together.’ And that’s what Jimmy Watt told this Yank. You know.

HH: And he was right.

NS: He was right.

HH: Tell us that story Neville about how your dad recognised his, his ground crew from, from his voice all those years later at a reunion.

NS: Oh yeah. We went to a reunion. My father was blind by this time and we were, we was walking to the church and it’s a hill to go up the church. My dad was blind and I had my dad on my arm. Well, this old guy came up and he says, stood in front of my father and he says. ‘You won’t remember me Able 1, will you?’ My father was blind. My father said, ‘Remember you?’ He says, ‘You saved our lives.’ He said, ‘You were the ground crew. We relied on you.’ And he remembered his voice and it was unbelievable. It was unbelievable. I can remember one time. This is a silly thing. I had to go to London. I had to go to get to the other side of London which is south London so I asked my father for directions. He said, ‘Come on. I’ll take you.’ I said, ‘Dad, you’re blind.’ He said, ‘I was a navigator wasn’t I?’ [laughs] So I said, ‘Yeah.’ So I’d got him in the car beside me and don’t forget he were blind but he directed me to exactly the place I wanted to be. ‘You take the next left.’ And it, and it was about a ten mile journey but I don’t know how he did it.

HH: He got you there.

NS: I don’t know how he did it. Another time [unclear] [pause] Oh yeah. Another time his pilot told me, he said, ‘We were coming in to land and they knocked the chimney pot off a farmhouse.’ But the next day the farmer came screaming, he said, ‘But we blamed somebody else.’ [laughs] But my father wanted to admit it. He said, ‘No. You don’t admit it. We blame somebody else.’ And he told me another other time as well it must be forty years after the war. Yeah, and he’d visited York because they used to go to York and he said, ‘I was sat in this café —' and this lady came up to him and she said, ‘Did you serve in the RAF?’ So, he said, ‘Yes.’ ‘I used to dance with you. Do you remember doing?’ And she used to dance with him at one of the dances in York. You know, he said, he said ‘It’s forty years ago and she still remembered.’ I said, ‘Dad, you’re an unforgettable person.’ You know.

HH: Was he a good dancer?

NS: Oh yeah. Supposed to have been, yeah. Yeah. I think that’s where I got it from.

HH: Are you a good dancer too?

NS: What are you laughing at [laughs] No. I can’t, I can’t even walk.

HH: Does dancing run in your family?

NS: I can’t even walk. Palestine. Jimmy Watt. I did this. Brenda Bernell. What’s Brenda Bernell? Oh. This is another story about my father in uniform. I was six years old and I was very ill. The doctor didn’t know what was wrong with me. He thought I had measles. But then he said it could be a bad case of flu because I came out in blotches and everything. Anyway, there was a girl that lived around the corner. I’ll never forget her name. Brenda Bernell. And she was in the same class as me so my grandmother had sent her a note to say, “Neville won’t be in school because he’s got measles.” That’s what they thought I had. When I finally got back to school teacher said, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ It turned out it were just a bad dose of flu. I said, ‘Well, I’ve had flu.’ And I had to stand outside the headmistress’s office for lying. Well, you know [laughs] So my father had come to visit me. And he said, he was at home so when I got home he was there. So, he said, ‘Why are you late?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve been outside the headmistress’s office for lying.’ He was angry with me. He said, ‘You’ve been lying?’ So I said, ‘Yeah. I just told them I’d got flu.’ And grandma said, ‘Well, that’s what it was but we sent a note saying he’d got —’[pause] My father marched me to school the next day in full uniform. I thought, oh, but the respect he got when he went through them school gates. The headmistress, she was all over him. You know. She couldn’t do enough for him. And I thought well she was a right cow anyway. Mrs [unclear] we called her Bumblebee.

HH: Did you get an apology?

NS: Oh, I got an apology, yeah. But when my father had gone I got, you know I still got picked on and what have you.

HH: So which, which schools did you go to in Leeds, Neville?

NS: Went to [unclear] Primary School and then to Foxwood Comprehensive School because Foxwood, it was the first comprehensive school in England and I had to write to my father because I had passed my Eleven-plus and had a choice of going to Roundhay School, or Coborn High School or another school. But I had to write to my father to say what, so he suggested Foxwood School. That will be the best in the future. That’s the only mistake he ever made I think [laughs] No. I did alright. I did alright. I did alright. But I can’t tell you about, I can’t tell you his missions what he did because I don’t know. I know there was a lot. I know he did more than anybody else.

HH: What happened to his logbook?

NS: His son’s got that in London.

HH: It does, it does survive though, does it?

NS: It might survive. I know, I know he’s got little things because he’s an hoarder and he’s, he’s not interested in any of this because when, when we was going up to the fiftieth reunion to meet all his old, his son was there and I said, ‘Akin, do you want to come up with us?’ ‘No. I’ll stay with mum.’ You know, he’s one of them type of things. I think he’s got, I know he’s got his ration book, things like that so he might have his logbook. But my father would have given it to me if he’d have known, you know, that he was going to die. He made sure.

HH: But that would probably have the fullest record of all his ops.

NS: Yeah. Yeah. But I don’t talk to the man. I don’t want to talk to him.

HH: No. There is another way of getting the information. Look, looking at operational record books.

NS: Yeah.

HH: Which is, which is possible but we can talk about that another time.

NS: Yeah. That’s fine.

HH: Maybe get some information from that.

NS: I just want, I just want to know how he was awarded his DFC. That’s all I’m interested in.

HH: And we’ll get, we’ll try.

NS: Yeah.

HH: And look for ways of —

NS: Yeah.

HH: Finding that information for you.

NS: I thought they might have let me know when I applied for his medals because my dad’s medals. Oh, my dad’s medals that’s another story.

HH: Tell us that story.

NS: Well, my father, when mother and father split up he got lodgings in this house not far and he had to go to London. So he asked this guy would he look after his medals until he comes back. He said, ‘Oh yeah. They’ll be safe with me.’ My dad didn’t get back for God knows how long and he went but the guy had moved and the medals had gone. Now, this guy had been seen at the Cenotaph in Leeds wearing my father’s medals. But we never, I had to get some copies made but my father, you know he said, ‘No. He wouldn’t have stolen them.’ I said, ‘Dad, he did. There are people like that, you know.’ My dad didn’t think there were people were like that. You know, why would anybody steal somebody else’s medals?

HH: Yeah.

NS: The guy had been in the RAF himself. But I think he was only ground crew but you know he was marching up and down with my dad’s medals on.

HH: So, did you, have you had those medals, the replacements? Did you get those for your dad or did you get those after he had passed away already?

NS: I got them for my dad but he said, ‘No, you keep them. You keep them there and then I’ll know you’ve got them then,’ you see.

HH: Yeah.

NS: So, I kept them up here.

HH: So, he knew that he had the replacements.

NS: Oh yeah. He, yeah I said, ‘I got your replacements. Don’t you worry about that.’

HH: Yeah.

NS: Anything else? I don’t [pause] it seems I had loads to tell you but I can’t think.

HH: Well, you have told us loads.

NS: Have I?

HH: You have. And I suppose it would be a good, a good way to end off really by talking about how the rest of your family feels about these stories because I know you’ve got children and grandchildren of your own.

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: Are they interested in these stories?

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: Do you tell them the stories?

NS: I do tell them now and then. Yeah. Like I said he’s —

Other: Yeah. My brother who lives in Spain. He’s got, he’s got all the photos up at his bar.

NS: Oh, he’s got a bar in Spain.

Other: He’s got all the photos of my granddad.

NS: They called the bar, “Banjos.” They call the bar, “Banjos.”

HH: Have you been out there?

Other: Yeah.

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah.

Other: Of course.

NS: We go out there. I go out regular and he has, well he’s got some more pictures now.

HH: So, you do keep this memory alive.

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah.

HH: Of your dad in the family. That’s wonderful.

NS: And it’s amazing how many people are interested in Spain because he’s got these pictures and he’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s my grandfather.’ But there’s so many. When I go now people want to talk, want talk to me about it you know. And there’s one guy, the one guy especially he runs a radio show in Malaga. And I think he’s mentioned it on the show in Malaga. You know. That’s another thing.

HH: So he should.

NS: Yeah.

HH: It’s important that these people do remember.

NS: It is. Yeah. It is. Yeah.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Yeah. So I’ve got to get some more pictures now and take them over when I go to fill his wall up you know. I’ve got, well, I’ve got plenty on my phone anyway, you know so—

HH: That’s great. Thank you so much for sharing all of these stories.

NS: It’s okay [unclear]

HH: And should you think of anymore which is doubtless going to happen take a note and we’ll come back and do some more chatting.

NS: Well, I’ll come and meet you. It’s not —

HH: It would be wonderful to welcome you in Lincoln.

NS: Yeah.

HH: It would be wonderful to take you around the new International Bomber Command Centre when it opens which will be next year.

NS: Yeah. I’d love to do it because there’s a guy I used to work with in Peterborough, an optician. And he’s really interested in this because his father was in the RAF. He was a —

HH: Do you stay in touch with him?

NS: Oh yeah. Gilbert. Yeah.

HH: Well, Lincoln is a good place for you to meet halfway.

NS: He lives in Boston.

HH: Oh, there you are. Boston and Leeds. You can meet in Lincoln.

NS: Yeah. He used, he used to have an optician shop in Boston. A Specsavers shop in Boston, this guy.

HH: One of the things that I just wanted to ask you before we close everything up is would you mind if we took some pictures of your photographs?

NS: No, not at all.

HH: Because if, if you are willing for us to be able to do that we would love to have copies put in to our archive as well.

NS: Yeah.

HH: For other people to have a look —

NS: Yeah.

HH: In future. So that would be really good. So, thank you Neville.

NS: Yeah.

HH: Perhaps the thing to do now would be to take some images and we also want a nice portrait of you.

NS: Oh, that’s okay.

HH: And we’ll take a portrait of Keeley too. Thank you so much.

NS: You’re welcome.

HH: Let’s stop all the equipment and take some still photographs and some other photographs. Is that okay, Alex?

[recording paused]

HH: Okay. Tell me about your dad’s love of jazz.

NS: Love of jazz. He loved jazz. He wanted to play it for his funeral, it was “Blue Indigo,” by oh I’ve got, I’ve got the CD down there.

HH: It’s, “Mood Indigo.”

NS: Mood. Well, it was, “Mood Indigo” It was “Blue Indigo,” because there’s, there’s so many different versions.

HH: Versions. Yeah.

NS: Because when I tried to get it afterwards because I’ve got a friend that has a record shop and he said, ‘There’s twenty different versions of this,’ but I’ve I’ve got the right one.

HH: And that’s what was played at his funeral.

NS: That was played at his funeral. Yeah.

HH: Lovely touch.

NS: It was so, the music. It just [pause] that’s it. You might not have heard of him Terry Gallagher the jazz singer. He’s great. That’s him there and that’s me just where I used to live in the centre of Leeds but he’d done a show there. How do you want to do these pictures then? Do you want to —?

[recording paused]

HH: Now, Neville, tell me the story about the brother you discovered much later.

NS: Well, about ten years ago my daughter, Keeley she rang me, she said, ‘Dad, you’ve got a brother.’ I said, ‘I know I’ve got a brother. I don’t talk to him.’ She said, ‘No. This is another one. He’s looking for you and he lives in America.’ So I finally, I phoned him and then he came over, didn’t he? He came over to see me and it took him three weeks. Now, he can’t stand the sight of the other one down there. I can’t tell you what he calls him over the phone. But he, but he’s a marvellous kid and he was brought up in care. His mother gave him up when he was three years old and he went to Durham. Now, this lady she just looked after half caste children. She fostered them. And what do you call the dressmaker? Bruce —

HH: I can picture him.

NS: The gay guy. Bruce.

Other: Bruce Oldfield.

NS: Bruce Oldfield.

HH: Oldfield.

NS: He was there in the same one. I used to have a picture. I used to have that book. A picture of Bruce Oldfield. But, now this guy they’re like brothers. Well, they are brothers. They were brought up as brothers and Bruce Oldfield lives in Italy now. He has a place in Italy. I think it’s Lake Como or somewhere, but he goes over there and visits him regular. You know he’s a smashing guy is Barry.

Other: They were in a band together.

NS: Oh he was in a band together, yeah.

Other: London Cowboys.

HH: Did you? Wow.

Other: London Cowboys he was in.

NS: No, he wasn’t in a band, what do you —

HH: But it was through this brother that you heard about us.

NS: Yeah. He, he phoned me and says I want you to do something about it. I said, ‘Look, I can’t send emails. I’m useless at that, you know.’ But luckily I had this guy next to me who used to live next door to me. He said, ‘I’ll do it for you.’ It’s why, just Dave emailing, I was telling him what to write. Anyway, I finally did and I told Barry. He said, ‘I want you to do it before he does it down there because he knows nothing.’ You know, that brother in London. He’d just do it for he’d make sure he got his name in print somewhere along the line. See if I can find out.

HH: Well. You must keep Barry informed and get him to come over when the, when the centre opens.

NS: Oh, we will do yeah.

HH: Come down and visit together. It would be wonderful.

Other: Yeah. Barry works in all the studios. Universal Studios.

NS: Yeah.

Other: Works on all the sets.

HH: Wow

NS: Find him —

Other: I’ll just click on the top of that.

NS: No problem.

HH: It’s been wonderful to meet you. Let’s start by talking a little bit about you and then we’ll get on to all the wonderful stories that you have collected, that you heard from your dad and that you are hopefully going to pass on to the rest of your family and a lots of other people besides. So I wonder if we could talk about you first Neville and where you were born and when.

NS: I was born on the 22nd of February 1945. I was born at number 22 Crawford Street, Leeds 2. Childhood was extreme. I can remember my childhood. I can remember being a baby. We was brought by my grandmother and grandfather. We lived with my grandmother and grandfather and it was wonderful. My father was away. I were born in ’45 but my father was still an officer in the Air Force and I think at that time he was in Palestine but he used to come home regular on leave. And it was really surprising because most children at that time had somebody in the armed forces, somebody in the family but when my father came home they used to love it because he was in an officer’s uniform and that felt really special, you know. For me, a little boy that felt really good. My mother and father split up when I was around about three, four years old and I stayed, I stayed with my grandparents. We moved to Seacroft when I was around about five years old. Moved to Seacroft in Leeds when I was about five years old and that was, that was a change because we moved out of the inner city to open fields but it was wonderful. It was absolutely marvellous and there were times when I thought things aren’t right you know because I was with my grandmother and grandfather. My mother used to live around the corner but I was happy living with my grandmother and grandfather. My father still came and visited. And then again in his officer’s uniform and all this. Kids used to come out in the street. Anyway, my father moved back then. He moved to London and I didn’t see him for quite a while. He used to write. I didn’t see him for quite a while. I think the last time I saw him when I was around about nine. He came up visiting. When I was twelve he asked me to go to London to visit him. I can remember my grandmother and grandfather putting me on a train to London. Twelve years old. I thought how exciting this is. Went to London. Stayed with my father but oddly enough after a week I was homesick [laughs] I missed, I missed my grandparents so I came home. But I used to go and visit regular. I had a friend who lived around the corner and his grandmother, he’d come and visit his grandmother but he came from Twickenham. I’ll never forget him. Tom Courtenay, they called him and I’m still in touch with him now and he came from Twickenham and he used to, he used to stay at his grandmother’s during the school holidays and I used to go and visit him. And then we used to go and visit my father. Now, I never saw my father again. I would write him but we lost all contact and I thought what’s happened? And I was eighteen and I had a letter from my father saying, ‘I’m remarrying. Would you come down and visit me?’ So I did. And he remarried again and I thought marvellous. He’s happy. He had another boy. That was good and I kept on visiting. But it wasn’t right, you know. I didn’t feel comfortable in his house with this strange woman. I don’t know why. I don’t know why I didn’t get on with her but there was something about her. But anyway, everything turned out okay. Now, about my father’s stories —

HH: Before we go onto your father’s stories how, just tell me a little bit about how, how your mum because you said she had been a WAAF?

NS: My mum was a WAAF, yeah.

HH: So tell us a little bit about your mum.

NS: My mum, she always said she couldn’t wait to be eighteen so she could join up. She always wanted to join up and she liked, well she wanted to join the Wrens because she liked the uniform better [laughs] but she joined the RAF. Now, she used to pack the parachutes and hand the parachutes out and that’s how she met my father because James Watt who was my father’s pilot who, Jimmy Watt but his real name was Reginald but he liked to be called Jimmy and he was going to, she told me this story that they were going to get their parachute and they have to give their name. So, she says, ‘Name?’ So Jimmy says, ‘Watt.’ So she says, ‘Name?’ So he says, ‘Watt.’ So she says, ‘What is your name?’ So he says he had to get his card and say, ‘Look, that is my name.’ And that, my father was behind and that’s how she met, that’s how she met my father, you know. So it’s just a funny story like that.

HH: And what happened to your mum after the war? What did she do?

NS: My mother. She, well, well she was pregnant during the war.

HH: Yeah.

NS: And so she was asked to leave. You had to leave the Air Force.

HH: Yeah. They had to didn’t they? Yeah.

NS: So, she left the Air Force and just carried on with life, you know. Well, left the Air Force, got married. They got married at Leeds Registry Office. They were supposed to get married in a church. I shouldn’t tell you this. They were supposed to get married in a church but my dad kept, there were going to be press there and my father didn’t want any press to be there and he changed, he changed it twice and they finally got married in Leeds Registry Office. Just so that there weren’t any press around. That’s how my father was. And my mother remarried. I’ve got six, six siblings on my mother’s side and they all live close as well.

HH: And you stay in touch with most of them?

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah. I’m going on holiday with them next month. With one of my sisters. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Carole. Yeah. They’ve all got families of their own now. Well, everybody has, you know. Grandparents and grandchildren. Yeah. We get on really great. All of them.

HH: Great.

NS: Yeah.

HH: So, let’s talk a little bit then I want to, I want to come back to the the way in which you have remembered your dad and the little, the shrine that you’ve created to your dad here. But I think, let’s go back and look at some, look at your dad’s time in the RAF and tell me how he came to be in Britain because he was Nigerian wasn’t he?

NS: My father was Nigerian. Yeah. He had two pals in Nigeria. They called them the [Coss], the [Coss] brothers —

HH: And you’ve got a picture there of them.

NS: [Aberwello], yeah. [Aberwella Ollawalli], Akin Shenbanjo and Adie [Campbell]. Not a very Nigerian name that Adie Campbell but only two arrived. My father and [Olliwello].

HH: Now, your father had tried to enlist in Nigeria and he was told that —

NS: Well, he didn’t try to enlist in Nigeria. He wrote to the War Office.

HH: Oh okay.

NS: He wrote to the War Office asking to join the RAF but I think this was 1941. The Battle of Britain. Everybody wanted to be a fighter pilot but the office, the War Office wrote back to him and said, “We aren’t recruiting from Nigeria at the moment.” So that’s it. My father wrote back insisting, ‘but I want to join.’ So, the War Office wrote back and said if you want to join you can make your way over to England and just go to the nearest recruiting office and join. You can take this letter with you and join. So my father had a scholarship to go to university. So he used the money that his father gave him to come over to England. That’s why my father could not go back. He was the oldest child. So he could never go back. He give, he give his right up and he’s never been back to Nigeria. He never went back to Nigeria. They came over. They got the boat. They got to the Recruiting Office at Southampton, they both went in to the Recruiting Office and said, ‘We’ve come to join the RAF.’ And they had, I don’t know whether he said they laughed at him but they just said, ‘Well, you can’t.’ But my father pulled this envelope out and said, ‘Oh.’ So the man said, ‘Well, alright. You’re in the RAF.’ That was it. Then they both joined together and my father’s friend during training he discovered he was scared of flying and so he had to go on ground crew. My father lost touch with him and that was that. My father was, I don’t know how he finished up at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. But that’s where he was and that’s where he met his pilot. Now, I was talking to Jimmy Watt. I said, ‘How did you meet my father?’ So, he said, ‘Well, I was walking around. I was walking around the base and I saw your dad sat on this wall so I approached him. I went over to him. I said, ‘Look, I can see all your ribbons,’ you know wireless operator, navigator. He said, ‘Have you not done all this training?’ So my father replied, ‘I’ve done so much training I could fight this war on my own.’ Well, Jimmy said to him, ‘Right, come with me,’ and that was it. They were settled from that moment on and I’m still in touch with Jimmy’s son. We phone regularly. Once a fortnight we’ll phone. There was a time, it was around about six years ago. I had a phone call to say that they was disbanding 76 Squadron. Well, it was only I used to go visit Spalding Moor. I used to go to all the reunions and everything. In fact, the school, a primary school there and the 76 Squadron has done so much for that school the children absolutely love it and they know all about the war and all that 76 Squadron did because they are teaching children about the war now. They never taught them about the war when I was a kid. We never got taught about the war. In fact, my grand, my grandson, Keeley’s son there was, they asked if there was anybody had got any grandparents, any old pictures? So I sent the pictures and my dad’s medals. They were flabbergasted. They were over the moon with that. Yeah. Anyway, go back to where were we?

HH: We were talking about your dad having got together with the pilot Jimmy Watt.

NS: Oh, he got, yeah he got together with pilot, Jimmy Watt.

HH: They flew in 76 Squadron obviously and they flew Halifaxes.

NS: They flew Halifaxes. Halifax. They named my father’s Halifax, “The Black Prince.” They didn’t like naming the planes at that time because they said, ‘Don’t name a plane because if a fighter gets the name of that plane or it shoots down something they’ll come looking for you.’ So my father said, ‘As long as I’m flying this plane nothing will happen.’ And nothing ever did. Now, my father flew so many missions because it was practically every night there was somebody goes ill or something like. Most like they just get scared. You think, this is it. It’s our time. And they don’t refuse to fly but my father would always volunteer to go. My father flew in most planes at that base. He told me about it because they thought, nobody would pick my father as crew, they thought he might be bad luck. I don’t know why. But when Jimmy Watt picked him up everybody thought he was good luck and so they were getting him to fly. I don’t know how my father got his DFC. I’ve never found out. He never told me and I’d like to find out how my father was awarded the DFC.

HH: It would be possible to find out.

NS: Yeah.

HH: We can do something about that.

NS: I’d like to find that out. Yeah. Yeah. Well, I can’t think now. I’m stuck.

HH: No. Not at all. So [pause] your dad would have flown with quite international crews because —

NS: Yes.

HH: There were Canadians —

NS: Yes. My father was, well the pilot was Canadian. Two Australians. A New Zealander. Two Australians, two New Zealanders and an Englishman. That was it. Nigerian.

HH: A really international crew.

NS: Nigerian, two New Zealanders, two Australians and an Englishman. That was it. Yeah.

HH: And they became like family didn’t they?

NS: Oh, well they all were family because they never, they were always together. You know, they all used to eat together and do everything together.

HH: Well, they had to look after each other.

NS: They had to look after each other.

HH: To come home safely I would think.

NS: They had to look after, they had to look after each other and they never made friends, never made close friends with any other, any other bombers because they were losing too many friends. They said they used to go in to the mess hall for breakfast on a morning there used to be two tables empty. You know. So —

HH: And did your dad’s entire crew survive the war?

NS: All of them survived the war.

HH: Remarkable.

NS: They all survived the war.

HH: That’s remarkable.

NS: They all survived the war. The plane was never, I heard a story when they finally had to leave the plane and the plane went up again it never came back. You know. So, and that’s, that’s supposed to be a true story. Yeah.

HH: And what happened to your dad after the war? Did he stay in the RAF for a while?

NS: He was in the RAF until 1953.

HH: Gosh.

NS: ’53 or ‘54 because I know he was, he told me this story and I shouldn’t really say this but I’ll tell you the story anyway. It’s coming out now. He was in where did I say he was? Not Israel. Palestine.

HH: Ah huh.

NS: He was in Palestine and he had this secretary. Now, she had relations in Leeds and she knew that my father came from Leeds and she asked him if she could send him some letters but my father, he read the letters first because he wasn’t allowed to send them, but he did post them for her. One day he was in the mess hall. He said, ‘We were just having a sing song round a piano and this secretary banged on the window and he said, ‘What do you want?’ ‘Will you come out with us for a drink?’ So he said, ‘I’m with my pal here.’ They said, ‘Well, bring him us. We’ll go out for a drink.’ And they left the base and they got a hundred yards down the road when the mess hall blew up. There was a bomb in the piano. Now, this, she must have known about it but she got my father out and I don’t, I know you shouldn’t of have wrote, read those letters.

HH: Don’t worry.

NS: But if he hadn’t have done he might have gone up in that.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Anyway, that’s another story.

HH: He was clearly a very lucky person.

NS: He was. Yeah. And a well liked person. It’s amazing. People have met him and they said, ‘Your father’s amazing.’ And I said, ‘Well why? He’s just a normal man.’ ‘No. He’s amazing.’ Even my friends you know, ‘Oh, your father’s so different.’ I said, ‘What do you mean so different? He’s just like your father.’ He said, ‘No. there’s something about him.’

HH: What do you think it was that people saw?

NS: I don’t know. I don’t know. But my grandparents. They loved him. I mean imagine 1945. Your daughter comes home with a black man.

HH: There was a lot more prejudice then then there is now yeah.

NS: Oh yeah. No. Well, no but my grandfather had seen my father. He used to be a boxer in the RAF and he’d seen him boxing.

HH: So was your dad a boxer as well?

NS: Yeah. Yeah. He was lightweight boxing. I think it was from all the Army, Navy and Air Force champion. Yeah. Yeah. And my father had seen him box you see. My grandfather. He must have boxed at Leeds Town Hall or something like that. That’s anyway they really liked my father. My grandparents.

HH: How do you remember your father? What was he like as a person? What was his personality like?

NS: It’s hard to say by me because he was strict but he wasn’t strict with me. Probably because we were distant or I don’t know. The distance between us in part but he was very strict but he was very moral. I know that. But he was very fair as well. A marvellous man. A really marvellous man.

HH: Did he ever wish, did he ever voice a wish to return to Nigeria or was he quite happy to stay here after the war?

NS: He was happy to stay here. He’d never been back to Nigeria. His son and his second wife they went to Nigeria. But my father never went.

HH: Did he maintain contact with his family there?

NS: Yes. Now, he had a sister. She was a nurse and I can remember her coming to visit us when we were living in, I was only four years old. Grace, they called her. I named that statue after her. Auntie Grace. She was marvellous. She was a nurse and she used to come to England. She used to go to St James’s Teaching Hospital. That’s in Leeds. And she used to learn things there and then go back. She used to come regular. And he had a brother who used to come over and he brought me my first pair of football boots. I never get it in London. You go out of Woolworths in London. I’ll never forget that. Yeah. Marvellous man. And he’s got there are so many Shenbanjo’s in England now it’s unbelievable.

HH: Oh, really. Well, there you are.

NS: If you go on Facebook —

HH: Okay.

NS: You find so many Shenbanjo’s and America, Australia. There are Shenbanjo’s all over the world now. Yeah.

HH: All over. Yeah.

NS: Yeah. You know, so he spread the word my father did.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Yes.

HH: So, but you it was after the war when, when you presumably, you know you’d finished school and you were becoming an adult. You, you, did you, you helped your dad quite a lot to stay in touch with squadron and so on and Squadron Associations —

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: And so on. Tell us about that.

NS: Well, I was, I used to go and visit. I worked in Peterborough and I used to go visit my father because London, Peterborough an hour’s drive. I would drive. So, he’d be North London. Kingsbury. So just an hour’s drive down the A1. One day I was there and my father said to me, ‘I want you to do something for me son.’ So I said, ‘Yeah. Whatever you want dad. I’ll do it.’ He said, ‘I want you to get the crew together that I flew with during the war.’ So, I said, ‘Okay dad.’ Just said it like that. I went out. I got in to the car and I’m driving up the A1 and all of a sudden I was thinking how can I do this? And I thought fifty years from now. That’s what he’s talking about. That’s what they said, ‘We’ll meet fifty years from now.’ I drove up the A1, got back to Peterborough. The next day I’ve come up to Leeds. I’ve called at my mother’s because my mother was a WAAF at 76 Squadron. And I said to her, ‘Look, he's asked me to do something.’ She said, ‘What?’ ‘He’s asked me to get the crew together he flew with during the war.’ Well, my mother looked at me stupid and she said, ‘Well, there was Jimmy Watt. He was a Canadian.’ I thought, ‘Well, I know that mum.’ She said, ‘But there was something on the television last night. It was about bombers flying from Holme-on -Spalding Moor.’ So the next day I went down to the studios, Leeds Studios. Television studios. I went to the reception desk and I told the receptionist what I was looking for. She said, ‘Look, I don’t think I can help you but just hang on.’ She went upstairs and she brought down the producer with her. Well, this producer said, ‘Look,’ he said, ‘I, I aren’t supposed to do this but I’m going to give you this video and you can watch it and if you find anything that’s okay but you must bring it back.’ So I said, ‘No problem. I’ll bring it back.’ I took the video, I watched it I couldn’t see anything on it. So I went back to this television studio the next week and I went to see the man. Look,’ I said, ‘I’m sorry. Thank you but I couldn’t find anything.’ So he said, ‘I want you to ring this number.’ He said, ‘It’s a lady. Patricia —' I’ve forgotten her second name.

HH: Was it Welbourne or something?

NS: Welbourne.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Patricia Welbourne. They used to call her Paddy. So I said what? ‘Oh, she used to work.’ She used to be, she was there and she was something to do with 76 Squadron. So I rang this lady in York and I said, ‘Mrs Welbourne?’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ Oh, I said, ‘You won’t know me. My name is Neville Shenbanjo.’ Well, she said, ‘I haven’t heard your voice in forty eight years.’ And I was, I said, ‘No. No, that’s my father. That’s my father.’ She said, ‘We’ve been looking for your father,’ you know, to get [pause] Anyway, that’s when it all started. She gave me the number of Jimmy Watt and I rang Jimmy Watt up in Canada. And that’s when it all started. I got three of them together. And I think five, five of them we all met once at one reunion. One guy had died and he’d lived just near my father. We got the rest together and marvellous. I’ve met Jimmy Watt three or four times.

HH: So you, so you made your dad’s wish come true.

NS: Oh yeah. Yeah. Yeah. He was over the moon about that. Yeah.

HH: Was he, was he really thrilled?

NS: Oh well, when he met Jimmy Watt after those years, there’s a picture on the wall there. Arms around each other.

HH: And where was that reunion? Was it —

NS: It was at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. At the —

HH: Okay.

NS: At the base. We, they still have reunions there but there’s not many people to go now.

HH: No.

NS: You know so it’s —

HH: But what, what about the next generation like you?

NS: Oh yeah.

HH: Do they still participate?

NS: They still go but it’s done mostly like everything else internet now and over the phone. You know. That’s how, that’s how, that’s how they communicate. But I haven’t been there for a while but I still like to go back every, what am I going to do this Sunday? I’m going to go visit there. There’s a funny story. We was there one day and I don’t know whether this is true or not but there one day there must have been thirty of us all there and this guy came. The place is an industrial estate now and this guy came up to, up to the crew and he says, he were the head of the security and he said, ‘I’ve got to tell you guys something.’ They said, ‘What?’ He said, well he was, one of his men was just going around the perimeter and security and he said he saw these kids playing football. So he thought that’s odd because it’s in the middle of nowhere this place. So the security man went up and there were kids playing football and he said they all had uniforms on. He said they had RAF uniforms on he said. And that man, he just ran back to the office and he said, ‘I’m not going back there.’ So they said it was the ghost of the —

HH: Yeah.

NS: But I didn’t believe it but the man never went back to work.

HH: He was convinced.

NS: He never went back to work.

HH: Yeah.

NS: So, I’ll tell you stories about my father then. What did he do? You know, it’s hard to say. It’s hard to —

HH: What did he do when he came out of the RAF?

NS: He, he went to work at the Post Office. Then he finished up as a chartered surveyor. I don’t know. I know he worked at the Post Office for a while and he went as a chartered surveyor.

HH: And all the time he was living in London was he?

NS: All the time he was living in London. Yeah. All the time he lived in London because I can remember when I was a kid my father used to send money up for me because my mum and father was divorced. And now and then this money didn’t arrive. My mother used to get angry about it. Anyway, the sad thing is we had a guy that lived around the corner and he was our postman and he was stealing the money.

HH: So your dad was sending the money.

NS: He was sending money but this post, anyway this postman finished up in jail for it. Then my father was forgiven for that. Yeah.

HH: How did you discover —

NS: Well, my father said, my father worked at the Post Office and he was sending it up registered. So, they just had to, I think they just —

HH: Yeah.

NS: They tricked this guy.

HH: Yeah. And sadly he went blind in his later years.

NS: My father went blind in his later years, yeah.

HH: And when did he pass away?

NS: Twenty five, twenty five years ago, I think.

HH: Gosh.

NS: Twenty five years.

HH: So it was in the ninety, late 1990s.

NS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, that’s when he passed away.

HH: And where is he buried?

NS: He’s, he was cremated.

HH: He was cremated.

NS: And it’s, and it’s, there was a plaque on the wall. It said, oh it’s in a crematorium in North London. I can’t remember.

HH: Okay. So, it’s in North London.

NS: It’s in North London.

HH: Yeah.

NS: Not far from Kingsbury.

HH: Okay.

NS: So, the crematorium there.

HH: And you were just telling me earlier that your mum survived a very long time and only passed away quite recently.

NS: Yeah. She was ninety one, my mother. Yeah. She’s passed.

HH: And she’d always lived, continued living in Leeds.

NS: Continued living in Leeds, yeah. She lived just up the road.

HH: And how come you found your way back to Leeds after you’d been in Peterborough? Where else did you travel and work?

NS: Well, I just happened to work in Peterborough. I just wanted a job and I’ve been an optical technician all my life. Since I was fifteen. And they were asking for somebody in Peterborough. So I went. I used to travel back to Leeds every weekend you know.

HH: So your home has always been in Leeds.

NS: My home has always, I’ve always had a home in Leeds. Yeah. Yeah.

HH: One of the things I wanted to, to ask you was how you, I mean obviously you have a very personal interest in how Bomber Command, RAF Bomber Command is remembered today. Do you think that, that Bomber Command is remembered adequately? Do you think that they’ve been given the respect or the recognition they deserve?

NS: They are now. At one time they was not. Not at all. My father regretted. My father made a lot of German friends. He used to visit Germany a lot. He liked Germany. He felt so guilty, you know. I remember my father bombed Dresden and places like this and after the war he used to feel, he felt so sad you know. He told me this. But what could he do? He had to do it and that were, that was the end of it. I was very proud of him naturally. And everybody else is. I had friends and they say to me, ‘Oh, your father. Oh yeah, he was an officer.’ And some still don’t believe me and I’d say, ‘Yes, he was an officer in the RAF.’ I can remember some guy once said to me, ‘No black men flew in the RAF.’ And this guy was in, this guy had been in the RAF, you know [laughs] I just laughed.

HH: Because I think, I mean don’t you think that that is an issue? That Bomber Command, you said earlier you know they didn’t have recognition for a long time but within, within that lack of recognition the, the black airmen and, and others who served in Bomber Command got even less recognition.

NS: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Probably. Probably. But I can’t see it though because my father was made an officer. So no. I don’t, I don’t think there was any prejudice in.

HH: No. But afterwards. The way in which Bomber Command has been remembered afterwards.