Good-bye Berlin

Title

Good-bye Berlin

Description

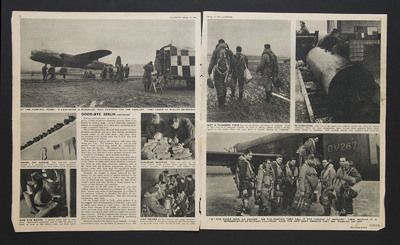

Article by Carl Olssen from 'Illustrated' magazine 19 February 1944. Comments on the operations to Berlin, on the poor living conditions on all the newly built airfields, outlines the preparations for an operation throughout the station. Numerous photographs showing various aspects of the stations activities including one of Lancaster DV267 with its eight man 'League of Nations' crew.

Date

1944-02-19

Temporal Coverage

Language

Format

Four page magazine article

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

PThompsonKG15010063, PThompsonKG15010064, PThompsonKG15010065

Transcription

February 19, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 5

[Photograph]

Good-bye, Berlin

[Photograph]

BEFORE THE RAID. Dressed and ready, suitably garbed against the intense cold of high altitude flying, a gunner takes a few minutes’ relaxation in the crew room before the signal to go out to his post in the aircraft

Carl Olsson and Cameraman R. Saidman visit a front-line bomber station which is helping to give Berlin the final K.O. The crews will soon be looking for a new No. 1 target

“THERE it is,” said our guide, pointing to a blob sticking up out of the East Anglian landscape. The blob only [italics] looked [/italics] like a dwarfish control tower but it might have been anything else, a barn, a grain silo, or an overgrown cowshed.

Our car turned down a lane not much better than a farm track, and as we got nearer the “blob,” we saw it was surrounded by a sea of Nissen huts.

“Here we are,” said our guide again, and we stepped out – ankle deep into rich, sticky, Fenland mud.

We paddled through the mud towards a block of hutments, catching distant glimpses of solid ground – concrete runways – wreathed in cold sea-mist – with the sombre looming shapes of Lancaster night bombers grouped at dispersal points, “front-line” stations rushed up in wartime to serve the needs of our ever mounting onslaught against Germany.

From dozens of stations like it our bomber squadrons have gone out night after night to blast and burn the heart out of Berlin and other military targets in Hitler’s Reich.

It was nearly a year since I had last visited an operational bombing station, and I found a lot of things changed, not least of which I would group under the heading of living amenities.

Gone are the days of central heating and the comfortable, brick-built living quarters of the so-called “permanent” stations. With few exceptions these have now been put to other purposes. And the R.A.F. has been very generous in handing over its best accommodation to our American and other Allies.

Officers and men live alike in the same kind of Nissen huts dumped down on “communal sites,” often with no such thing as “water laid on” and with a mile and more of unmade roads separating them from their messes and their working quarters.

The nearest town with a couple of pubs and one picture palace is often several miles away, and R.A.F. regulations, harder on petrol restrictions than most civilian authorities, allow no free transport to get there.

OVER

[page break]

6 ILLUSTRATED – February 19, 1944

[Photograph]

AT THE CONTROL POINT. A LANCASTER IS SIGNALLED INTO POSITION FOR THE TAKE-OFF. THEY LEAVE AT MINUTE INTERVALS

[Photograph]

SHOES ON PARADE. This front-line bomber station is a quagmire. Everybody wears gumboots. These shoes are waiting for their owners in the cloakroom

[Photograph]

AND THE BOOTS. A picture which tells its own story. Mud-caked gumboots wait to take the place of shoes as soon as the officers come out from lunch

GOOD-BYE, BERLIN – continued

Station entertainment is limited to a cinema projector. ENSA shows are unknown because there is no timber to build a stage. It is a front-line existence almost as completely as if they were operating from newly conquered territory.

But if they grumble a bit (and who wouldn’t) they grumble cheerfully and give their station nicknames usually based on the word mud. And they carry on working even harder than the R.A.F. has ever done before in its history.

This station I visited, for instance, only came into being last July. The bombers flew in, and air and ground crews arrived long before the constructor’s men were off the site. The aircrew were over Germany the day after their arrival at the new station. Since that day they have taken several thousand tons of bombs to Germany – most of them to Berlin.

Such a load in so short a time (and you must allow for long periods of non-flying weather) is some measure of the tempo of destruction which Bomber Command has built up from these front-line stations, and of the sweat and toil of those anonymous heroes, the ground crews, who have kept the squadrons flying sometimes on several [italics] consecutive [/italics] nights of operations.

Multiply the weight of attack achieved by this station by the many scores of similar stations in the command and one begins to realize why the great city of Hamburg has vanished from the lists of the world’s ports and why Berlin is being erased as a centre of the German war machine.

Even now, in the fifth year of the war, and after endless series of communiques, streams of “eye witness” stories and miles of photographs, it is difficult for ordinary civilians to visualize the effect of concentrated [italics] aerial [/italics] bombardment. But the following comparison may help.

On the Sangro front in Italy, often spoken of as the biggest [italics] land [/italics] bombardment of this war, 1,400 tons of shells came down in [italics] eight hours [italics]. On the Fifth Army front 100,000 of our shells, i.e. between 2,000 and 2,400 tons, went down in [italics] eighteen hours [/italics]. Remember these were fronts many miles in length and mostly open country. Yet they smashed the German defence and prisoners spoke of the astounding paralysing effect of these heavy bombardments.

And now compare the figures of air assault. To take one instance only, on the night of January 20/21 this

[Photograph]

AIRCREWS’ RATIONS. Here are some of the ration parcels being checked before take-off. Parcels contain chocolate, chewing-gum, milk tablets, etc.

[Photograph]

HOT DRINKS for the bitterly cold upper altitudes. Each member of the aircrew brings his own Thermos flask to the crew room where he fills it with tea or coffee

[page break]

February 19, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 7

[Photograph]

NOT A FLANDERS FIELD but an aerodrome somewhere in England. Some of the crew of a Lancaster bomber, [italics] en route [/italics] to Berlin paddle across a muddy carpet to the trucks which will take them to aircraft waiting at “dispersal.”

[Photograph]

BLOCKBUSTER. One view of the rarely seen 4,000-lb. bomb – but often [italics] felt [/italics] within Germany. They call them blockbusters there because their appalling blast shifts whole blocks of buildings. Wall symbols denote this station’s raid activities.

[Photograph]

“K” FOR KING’S CREW GO ABOARD. ON THE STATION THEY CALL IT THE “LEAGUE OF NATIONS” CREW BECAUSE IT IS REPRESENTATIVE OF SO MANY COUNTRIES. NOTE THE NEW BODY ARMOUR THEY ARE WEARING ON TEST

OVER

[page break]

8 ILLUSTRATED – February 19, 1944

[Photograph]

AFTER THE RAID. The crew of “U” for Uncle, first back from Berlin, report to technical officers, veteran raiders themselves, about the night’s “show.” They report to these experts before the normal interrogation

[Photograph]

SOME OF THE RESULTS. A picture, obtained from neutral sources, of the damage in Charlottenburg quarter of Berlin. This suburb is the centre of many important war industries. It has received some of the heaviest attacks

GOOD-BYE BERLIN – continued

year, 2,300 tons of bombs went down on Berlin [italics] in thirty minutes [/italics]! There have been similar loads in even shorter time on that city.

Remember, too, that the bombs are falling into built-up areas, on a shorter front than a land attack. Remember, too, that, tonnage for tonnage, a bomb contains a much higher explosive charge than a shell.

No city, no defence system, can stand up under such attacks, scientifically delivered, as Bomber Command is now making.

Every major raid over Germany is now like a big land battle, planned and conducted just as meticulously and entailing the same amount of prodigious human effort. As the scale of attacks has mounted, as living conditions at R.A.F. stations have become more and more Spartan, so the operational routine has changed from a year ago.

One innovation is the employment of “leaders” in the various skills which make up an aircrew. These men – bomb leader, gunnery leader, navigation leader, engineer leader, etc. – take a lot of work off the shoulders of the wing commanders and the station commander.

They are all experts at their jobs, veterans of many raids into enemy territory – some of them running into three figures – and they form a sort of permanent Brains Trust at each station, guiding and advising the aircrews for which they are responsible, as well as the executive officers at the station.

It is a system which makes for great efficiency and speed in laying on operations, lower casualties and more successful attacks. These “leaders” need never fly on ops again, though of course a good many of them do, “just to keep their hands in.”

Picture the routine as it is now (and as it was at this station I visited on the day of a big Berlin raid). A signal comes through from Group H.Q. (who in turn has got it from Bomber Command) at about 10 a.m., briefly intimating that ops are on that night, that “maximum effort” is required and asking how many aircraft can be “offered” from that station. The wing commander calls a conference at which all the “leaders” are present.

First to report is the engineer officer, with his little board chalked with the name and degree of serviceability of all the bombers on the station. He says he can “offer” so many aircraft for that night with certainty, and gives their names. This information is signalled to group and then the conference gets down to the business of picking crews.

No target has yet been mentioned until another signal comes in giving some indication of it and stating the bomb load and composition. The navigation leader plots out rough courses on his chart and the conference then works out the petrol load and safety margins required. The whole machinery of the station swings into action.

At the bomb dumps the handlers are rolling out the 4,000 lb. “cookies” and the big incendiary containers for loading up. Maintenance and ground crews are swarming over the bombers at dispersal points, checking and adjusting. Petrol and oil are being drawn from the storage. (A 700-bomber attack on Berlin uses up 1,500,000 gallons of petrol.) Waafs in the kitchen are cutting sandwiches for the crews, packing rations of chocolate, chewing gum and milk tablets.

In the locker rooms other ground staff are getting out equipment for each of the aircrew – silk and electrically heated clothing, flying suits, boots, Mae Wests, all the massive impedimenta each man carries with him.

If it is a daylight take-off, briefing is early. From that moment the station is cut off by telephone from all the outside world. The crews go from the “briefing” to their “operational meal” (usually an egg) and from there to the crew room to change into flying kit.

They talk to nobody (except to those who were at the briefing) about their target; not even to their own ground crews.

An hour before take-off they are at their machines. And then at slightly over minute intervals, more regularly than a train service, they are signalled down the runway to join the great host from the other stations at the appointed rendezvous, and to fill the night sky above Germany with the appalling giant beat of their massed engines.

Good-bye Berlin!

[Photograph]

Good-bye, Berlin

[Photograph]

BEFORE THE RAID. Dressed and ready, suitably garbed against the intense cold of high altitude flying, a gunner takes a few minutes’ relaxation in the crew room before the signal to go out to his post in the aircraft

Carl Olsson and Cameraman R. Saidman visit a front-line bomber station which is helping to give Berlin the final K.O. The crews will soon be looking for a new No. 1 target

“THERE it is,” said our guide, pointing to a blob sticking up out of the East Anglian landscape. The blob only [italics] looked [/italics] like a dwarfish control tower but it might have been anything else, a barn, a grain silo, or an overgrown cowshed.

Our car turned down a lane not much better than a farm track, and as we got nearer the “blob,” we saw it was surrounded by a sea of Nissen huts.

“Here we are,” said our guide again, and we stepped out – ankle deep into rich, sticky, Fenland mud.

We paddled through the mud towards a block of hutments, catching distant glimpses of solid ground – concrete runways – wreathed in cold sea-mist – with the sombre looming shapes of Lancaster night bombers grouped at dispersal points, “front-line” stations rushed up in wartime to serve the needs of our ever mounting onslaught against Germany.

From dozens of stations like it our bomber squadrons have gone out night after night to blast and burn the heart out of Berlin and other military targets in Hitler’s Reich.

It was nearly a year since I had last visited an operational bombing station, and I found a lot of things changed, not least of which I would group under the heading of living amenities.

Gone are the days of central heating and the comfortable, brick-built living quarters of the so-called “permanent” stations. With few exceptions these have now been put to other purposes. And the R.A.F. has been very generous in handing over its best accommodation to our American and other Allies.

Officers and men live alike in the same kind of Nissen huts dumped down on “communal sites,” often with no such thing as “water laid on” and with a mile and more of unmade roads separating them from their messes and their working quarters.

The nearest town with a couple of pubs and one picture palace is often several miles away, and R.A.F. regulations, harder on petrol restrictions than most civilian authorities, allow no free transport to get there.

OVER

[page break]

6 ILLUSTRATED – February 19, 1944

[Photograph]

AT THE CONTROL POINT. A LANCASTER IS SIGNALLED INTO POSITION FOR THE TAKE-OFF. THEY LEAVE AT MINUTE INTERVALS

[Photograph]

SHOES ON PARADE. This front-line bomber station is a quagmire. Everybody wears gumboots. These shoes are waiting for their owners in the cloakroom

[Photograph]

AND THE BOOTS. A picture which tells its own story. Mud-caked gumboots wait to take the place of shoes as soon as the officers come out from lunch

GOOD-BYE, BERLIN – continued

Station entertainment is limited to a cinema projector. ENSA shows are unknown because there is no timber to build a stage. It is a front-line existence almost as completely as if they were operating from newly conquered territory.

But if they grumble a bit (and who wouldn’t) they grumble cheerfully and give their station nicknames usually based on the word mud. And they carry on working even harder than the R.A.F. has ever done before in its history.

This station I visited, for instance, only came into being last July. The bombers flew in, and air and ground crews arrived long before the constructor’s men were off the site. The aircrew were over Germany the day after their arrival at the new station. Since that day they have taken several thousand tons of bombs to Germany – most of them to Berlin.

Such a load in so short a time (and you must allow for long periods of non-flying weather) is some measure of the tempo of destruction which Bomber Command has built up from these front-line stations, and of the sweat and toil of those anonymous heroes, the ground crews, who have kept the squadrons flying sometimes on several [italics] consecutive [/italics] nights of operations.

Multiply the weight of attack achieved by this station by the many scores of similar stations in the command and one begins to realize why the great city of Hamburg has vanished from the lists of the world’s ports and why Berlin is being erased as a centre of the German war machine.

Even now, in the fifth year of the war, and after endless series of communiques, streams of “eye witness” stories and miles of photographs, it is difficult for ordinary civilians to visualize the effect of concentrated [italics] aerial [/italics] bombardment. But the following comparison may help.

On the Sangro front in Italy, often spoken of as the biggest [italics] land [/italics] bombardment of this war, 1,400 tons of shells came down in [italics] eight hours [italics]. On the Fifth Army front 100,000 of our shells, i.e. between 2,000 and 2,400 tons, went down in [italics] eighteen hours [/italics]. Remember these were fronts many miles in length and mostly open country. Yet they smashed the German defence and prisoners spoke of the astounding paralysing effect of these heavy bombardments.

And now compare the figures of air assault. To take one instance only, on the night of January 20/21 this

[Photograph]

AIRCREWS’ RATIONS. Here are some of the ration parcels being checked before take-off. Parcels contain chocolate, chewing-gum, milk tablets, etc.

[Photograph]

HOT DRINKS for the bitterly cold upper altitudes. Each member of the aircrew brings his own Thermos flask to the crew room where he fills it with tea or coffee

[page break]

February 19, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 7

[Photograph]

NOT A FLANDERS FIELD but an aerodrome somewhere in England. Some of the crew of a Lancaster bomber, [italics] en route [/italics] to Berlin paddle across a muddy carpet to the trucks which will take them to aircraft waiting at “dispersal.”

[Photograph]

BLOCKBUSTER. One view of the rarely seen 4,000-lb. bomb – but often [italics] felt [/italics] within Germany. They call them blockbusters there because their appalling blast shifts whole blocks of buildings. Wall symbols denote this station’s raid activities.

[Photograph]

“K” FOR KING’S CREW GO ABOARD. ON THE STATION THEY CALL IT THE “LEAGUE OF NATIONS” CREW BECAUSE IT IS REPRESENTATIVE OF SO MANY COUNTRIES. NOTE THE NEW BODY ARMOUR THEY ARE WEARING ON TEST

OVER

[page break]

8 ILLUSTRATED – February 19, 1944

[Photograph]

AFTER THE RAID. The crew of “U” for Uncle, first back from Berlin, report to technical officers, veteran raiders themselves, about the night’s “show.” They report to these experts before the normal interrogation

[Photograph]

SOME OF THE RESULTS. A picture, obtained from neutral sources, of the damage in Charlottenburg quarter of Berlin. This suburb is the centre of many important war industries. It has received some of the heaviest attacks

GOOD-BYE BERLIN – continued

year, 2,300 tons of bombs went down on Berlin [italics] in thirty minutes [/italics]! There have been similar loads in even shorter time on that city.

Remember, too, that the bombs are falling into built-up areas, on a shorter front than a land attack. Remember, too, that, tonnage for tonnage, a bomb contains a much higher explosive charge than a shell.

No city, no defence system, can stand up under such attacks, scientifically delivered, as Bomber Command is now making.

Every major raid over Germany is now like a big land battle, planned and conducted just as meticulously and entailing the same amount of prodigious human effort. As the scale of attacks has mounted, as living conditions at R.A.F. stations have become more and more Spartan, so the operational routine has changed from a year ago.

One innovation is the employment of “leaders” in the various skills which make up an aircrew. These men – bomb leader, gunnery leader, navigation leader, engineer leader, etc. – take a lot of work off the shoulders of the wing commanders and the station commander.

They are all experts at their jobs, veterans of many raids into enemy territory – some of them running into three figures – and they form a sort of permanent Brains Trust at each station, guiding and advising the aircrews for which they are responsible, as well as the executive officers at the station.

It is a system which makes for great efficiency and speed in laying on operations, lower casualties and more successful attacks. These “leaders” need never fly on ops again, though of course a good many of them do, “just to keep their hands in.”

Picture the routine as it is now (and as it was at this station I visited on the day of a big Berlin raid). A signal comes through from Group H.Q. (who in turn has got it from Bomber Command) at about 10 a.m., briefly intimating that ops are on that night, that “maximum effort” is required and asking how many aircraft can be “offered” from that station. The wing commander calls a conference at which all the “leaders” are present.

First to report is the engineer officer, with his little board chalked with the name and degree of serviceability of all the bombers on the station. He says he can “offer” so many aircraft for that night with certainty, and gives their names. This information is signalled to group and then the conference gets down to the business of picking crews.

No target has yet been mentioned until another signal comes in giving some indication of it and stating the bomb load and composition. The navigation leader plots out rough courses on his chart and the conference then works out the petrol load and safety margins required. The whole machinery of the station swings into action.

At the bomb dumps the handlers are rolling out the 4,000 lb. “cookies” and the big incendiary containers for loading up. Maintenance and ground crews are swarming over the bombers at dispersal points, checking and adjusting. Petrol and oil are being drawn from the storage. (A 700-bomber attack on Berlin uses up 1,500,000 gallons of petrol.) Waafs in the kitchen are cutting sandwiches for the crews, packing rations of chocolate, chewing gum and milk tablets.

In the locker rooms other ground staff are getting out equipment for each of the aircrew – silk and electrically heated clothing, flying suits, boots, Mae Wests, all the massive impedimenta each man carries with him.

If it is a daylight take-off, briefing is early. From that moment the station is cut off by telephone from all the outside world. The crews go from the “briefing” to their “operational meal” (usually an egg) and from there to the crew room to change into flying kit.

They talk to nobody (except to those who were at the briefing) about their target; not even to their own ground crews.

An hour before take-off they are at their machines. And then at slightly over minute intervals, more regularly than a train service, they are signalled down the runway to join the great host from the other stations at the appointed rendezvous, and to fill the night sky above Germany with the appalling giant beat of their massed engines.

Good-bye Berlin!

Collection

Citation

“Good-bye Berlin,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed November 5, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/17700.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.