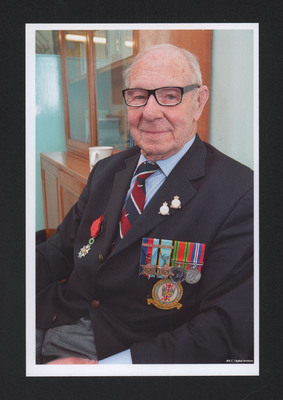

Interview with Geoff Payne

Title

Interview with Geoff Payne

Description

Geoff Payne has his first experience of the Royal Air Force with the Air Training Corps, at RAF Wyton in Cambridgeshire, where he had one of his first experiences of military humour. He joined in 1943 at the age of 17 and a half hoping to become a pilot - he took the faster option because of his young age and trained as an air gunner.

Basic training was carried out at Lords Cricket ground in London. One clear memory is helping to carry patients down several flights of stairs from a nearby hospital during an air raid.

Time was spent at RAF Bridlington on Initial Training Wing before attending Air Gunnery School in the Isle of Man. Further training was undertaken at RAF Banbury where he was crewed up on Wellingtons, before moving to the Heavy Conversion Unit at Wratting Common to convert to Stirlings. During his time here he attended an escape course at RAF Feltwell and was instructed in unarmed combat, which he dismissed as pitiful.

He and his crew were posted to RAF Witchford, Cambridgeshire, where he flew his first operation in February 1944 replacing an ill air gunner. He later discovered this was an inexperienced crew. He remembers the target was around Osnabrück in Germany and it was a melee over the target where they were attacked by two Me 109s, which they successfully shook off. On his return, he remembers being unable to sleep and went for a walk into Ely. There he discovered the Oxford Cambridge boat race was being held and watched it

Target areas of Germany included Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Augsburg. On his 5th operation, the aircraft was attacked, and the aircraft lost its heating and communications. He suffered frostbite and spent several months recovering in Ely hospital.

On regaining fitness, he was transferred to RAF Waterbeach and was allocated to a crew led by Ted Cousins. Waterbeach was a pre-war airfield with comfortable facilities. Time off was spent competing in athletics and football along with drinking at the local public houses.

When time allowed, he went home, but found the experience boring: all his friends were serving away, and there was little to do except drink or go to the cinema. His elder brother was serving as a navigator in the Far East, and he felt it unfair to talk about his experiences with his family.

At RAF Waterbeach there was a greater variety of operations. Targets varied from Germany to Southern France. He also remembers one trip to Poland. This entailed flying over Denmark and they could see the lights from Sweden and anti-aircraft fire.

He has a clear memory of most of his operations but does not wish to dwell on some. On one occasion he spotted a Me 109, he tried to warn the pilot but his intercom had frozen and emergency light was inoperative. He tried to open fire but his guns jammed – the night fighter opened fire and hit the centre of the aircraft. The aircraft began violently manoeuvring and he wasn’t sure if this was deliberate evasive manoeuvres or if they were out of control. He made his way forward and discovered the aircraft door open and the mid upper gunner missing. There were cannon holes all around the centre of the aircraft. He still wasn’t sure if he was the only one on board until he reached the main cabin and found the rest of the crew in position. They made it back home where they realised an incendiary bullet was lodged in the ammunition pannier.

His last operation was one of the thousand-bomber operations in Germany, the air black with anti-aircraft fire. On his return, the air gunners went sent to the bomb dump to assist the armourers in preparing the bombs for the following days attack which was carried out by the United States Army Air Forces.

After completing his tour of operation, he was posted to RAF Brackla, hoping to be retained as physical training instructor, but ended up at RAF Weeton near Blackpool to be trained as a driver.

He served at several locations across Southern England before his final posting which was with a microfilm unit in Frankfurt. Fraternising with locals was not allowed, but he did manage to learn German. He played in a football match against a much better German select team.

After demob, he returned home and was involved in the manufacturing of cars at the Triumph factory. He married, and because of unrest and strikes in the car industry, he moved to Scotland and was employed at the Carron company in Falkirk as a production director manufacturing steel bars, where his ability to speak German became an advantage in his dealings with foreign companies. He met an ex Luftwaffe pilot and experiences were exchanged - there was no animosity whatsoever and it was accepted they both had been carrying out their duty.

Geoff looks back on his time in Bomber Command with great fondness. It was like a big family. He still has contact with surviving crew members, and still attends reunions.

Basic training was carried out at Lords Cricket ground in London. One clear memory is helping to carry patients down several flights of stairs from a nearby hospital during an air raid.

Time was spent at RAF Bridlington on Initial Training Wing before attending Air Gunnery School in the Isle of Man. Further training was undertaken at RAF Banbury where he was crewed up on Wellingtons, before moving to the Heavy Conversion Unit at Wratting Common to convert to Stirlings. During his time here he attended an escape course at RAF Feltwell and was instructed in unarmed combat, which he dismissed as pitiful.

He and his crew were posted to RAF Witchford, Cambridgeshire, where he flew his first operation in February 1944 replacing an ill air gunner. He later discovered this was an inexperienced crew. He remembers the target was around Osnabrück in Germany and it was a melee over the target where they were attacked by two Me 109s, which they successfully shook off. On his return, he remembers being unable to sleep and went for a walk into Ely. There he discovered the Oxford Cambridge boat race was being held and watched it

Target areas of Germany included Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Augsburg. On his 5th operation, the aircraft was attacked, and the aircraft lost its heating and communications. He suffered frostbite and spent several months recovering in Ely hospital.

On regaining fitness, he was transferred to RAF Waterbeach and was allocated to a crew led by Ted Cousins. Waterbeach was a pre-war airfield with comfortable facilities. Time off was spent competing in athletics and football along with drinking at the local public houses.

When time allowed, he went home, but found the experience boring: all his friends were serving away, and there was little to do except drink or go to the cinema. His elder brother was serving as a navigator in the Far East, and he felt it unfair to talk about his experiences with his family.

At RAF Waterbeach there was a greater variety of operations. Targets varied from Germany to Southern France. He also remembers one trip to Poland. This entailed flying over Denmark and they could see the lights from Sweden and anti-aircraft fire.

He has a clear memory of most of his operations but does not wish to dwell on some. On one occasion he spotted a Me 109, he tried to warn the pilot but his intercom had frozen and emergency light was inoperative. He tried to open fire but his guns jammed – the night fighter opened fire and hit the centre of the aircraft. The aircraft began violently manoeuvring and he wasn’t sure if this was deliberate evasive manoeuvres or if they were out of control. He made his way forward and discovered the aircraft door open and the mid upper gunner missing. There were cannon holes all around the centre of the aircraft. He still wasn’t sure if he was the only one on board until he reached the main cabin and found the rest of the crew in position. They made it back home where they realised an incendiary bullet was lodged in the ammunition pannier.

His last operation was one of the thousand-bomber operations in Germany, the air black with anti-aircraft fire. On his return, the air gunners went sent to the bomb dump to assist the armourers in preparing the bombs for the following days attack which was carried out by the United States Army Air Forces.

After completing his tour of operation, he was posted to RAF Brackla, hoping to be retained as physical training instructor, but ended up at RAF Weeton near Blackpool to be trained as a driver.

He served at several locations across Southern England before his final posting which was with a microfilm unit in Frankfurt. Fraternising with locals was not allowed, but he did manage to learn German. He played in a football match against a much better German select team.

After demob, he returned home and was involved in the manufacturing of cars at the Triumph factory. He married, and because of unrest and strikes in the car industry, he moved to Scotland and was employed at the Carron company in Falkirk as a production director manufacturing steel bars, where his ability to speak German became an advantage in his dealings with foreign companies. He met an ex Luftwaffe pilot and experiences were exchanged - there was no animosity whatsoever and it was accepted they both had been carrying out their duty.

Geoff looks back on his time in Bomber Command with great fondness. It was like a big family. He still has contact with surviving crew members, and still attends reunions.

Creator

Date

2017-05-28

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Coverage

Language

Type

Format

00:32:26 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

APayneGA170528, PPayneG1702, PPayneG1701

Transcription

BJ: So, this interview is being conducted for the International Bomber Command Centre. The interviewer is Brenda Jones. The person being interviewed is Geoffrey Payne. The interview is taking place in Mr. Payne’s home in Cumbernauld on the 28th of May 2017. Mr. Payne, thank you for agreeing to talk to me today. Could you tell me about your life before you joined the RAF?

GP: Well, my life was a bit raggedy, I was an apprentice to Sheet Metal Work and worked in a company in the centre of Birmingham and we were manufacturing spats for Lysander aircraft and making fire pumps, things like that and more interested in sports than anything else [laughs].

BJ: And how did you come to join the RAF?

GP: Well, I joined the Air Training Corps, which I was one of the original members and it was the Air Training Corps was at Birmingham was the Austin Motor Company Squadron which was 480 and 479, there were two squadrons in the, ATC squadrons, and that’s why I started to get involved with the, with the Air Force, thinking a lot about the Air Force at the time. We went to camp to RAF Weeton, which was a Pathfinder Squadron, 7 Squadron, which were flying Stirlings and the most funniest part about us, we wanted to go into St Yves for the evening and we had to know a password to go out of the place because there was operations on that night and they said the password was WATER, which was this, I think they were pulling our legs or something like that, they said because the Germans can’t sound the w’s is wasser, so that was the sort of thing, that gave me a great interest in the Air Force.

BJ: OK. And when did you come to join the Air Force?

GP: I joined when I was seventeen and a half and I went to Vishyde Close in Birmingham to get assessed and I was assessed as a pilot and I was given a number and then sent back to work again because they wouldn’t call me up until I was eighteen but in the meantime I had a letter from them saying that it would possibly take far too long for me to become a pilot and that they’d had other vacancies in the Air Force which was an air gunner so I decided to do that.

BJ: And what year was this?

GP: 1943, yes.

BJ: And what happened when you started with the RAF?

GP: What happened?

BJ: Yes, what did your training involve?

GP: The training, we went to London, to Lord’s Cricket Ground and then we were put into high-rise flats and then we had our meals at the London zoo and used to march there every, for breakfast those [unclear] and tea and there’s one occasion there when there was a heavy air raid and at Lord’s Cricket Ground there’s the Regent’s Park and [unclear] anti-aircraft comes and we had to move out and go to another set of flats which was a hospital, which the RAF hospital, and carry all the patients down from the high floors cause they wouldn’t, couldn’t go down in the lifts and carry the, down in stretchers into the basement and back up then and then after that initial training, I went to Bridlington for ITW and that’s a nice seaside place, enjoyed it there and then off we went to Air Gunners School which was in the Isle of Man, just outside Ramsey, a place called Andreas and then, after three months of training, we were sent to an ITW, which was in Banbury where we were crewed up and flew in Wellingtons and from then we, we had to go to Heavy Conversion Unit which was a Stirling set-up, a place called Wratting Common in Cambridgeshire and we did that and then also we moved to, did an escape course at Feltwell and which was hilarious and then.

BJ: What did they teach you there about escaping?

GP: Unarmed combat and this sort of thing but it was, it just became a laugh actually [laughs] so, but we were there for the week and then we went back onto Wratting Common on Stirlings but at that time the Stirlings was being phased out from operations in the, for the main force in Bomber Command and we were transferred to, onto Lancasters which were radial engines Mark II, Hercules engines and from then we did a couple of weeks training there before we were put onto the squadron.

BJ: How did you find the Lancasters compared to the Stirlings?

GP: I didn’t like the Stirlings at all.

BJ: Ah!

GP: No, they frightened me because whilst I was converting onto Stirlings, I had to go to Newmarket to do a short gunnery course there and in the meantime my crew then crashed one of the Stirlings at [unclear] market so and but I, they phased these Stirlings out and that’s why I went on to Lancasters and then from Lancasters on Waterbeach we moved to a squadron which was RAF Witchford.

BJ: Ok. What happened when you got to Witchford?

GP: [laughs] We arrived at Witchford and then the following day we had to go round, signing in, which is a normal thing, you go to all the various sections and sign in and so forth like that and you get your billets and that and I went to the gunnery leaders office to sign in there and he says, ah yes, he says, you’re on tonight and that was the second day I was there [laughs] and I was, I said, what for? He says, well, there’s a rear gunner taken ill and you’ll have to, you’ll be flying with Lieutenant Speelenburg who was South African.

BJ: How did you feel about that?

GP: Terrible, it was, it was, to do a first op with a sprog crew which, the crew was a, they hadn’t done any operations before anyway and I hadn’t done any operations so they obviously bloodied with a new crew and that was one of the most horrendous air raids I’ve been on and that was to Augsburg, in southern Germany which was an eight hour journey, it was the most frightening experience I’ve ever had in my life so.

BJ: What happened on the mission?

GP: Oh, we got attacked over the target by a, by two Messerschmitt 109s, well, we got through that alright but it was, I never in my life would have expected to witness such a melee which was over the target, and I thought to myself I’m not coming out through this loss.

BJ: Do you remember what the target was?

GP: Augsburg.

BJ: Yes.

GP: It was the MAN works.

BJ: Ok.

GP: So that was, it was a night trip, eight-hour trip.

BJ: And did you stay with that crew then after?

GP: No, no.

BJ: No. So, how did you get assigned to a crew?

GP: I’d already got my crew,

BJ: Oh, ok.

GP: From, from Banbury, from Chipping Warden. I’d already got my crew, my crew were there but they were doing cross country south. So that was me doing me first op and I thought, I’ll never gonna get through this. So, that was my first operation and in the morning I couldn’t get off to sleep so I decided to, I walked into Ely and the Oxford and Cambridge boat race was on there so that was the, because they didn’t have the boat races in London because of the bombings, so I saw the boat race there.

BJ: Oh, ok.

GP: And came back, that’s it, so I said, no, that’s it, you can’t, you got to, maybe get through this alright but just forget about it and take it as it comes.

BJ: Ok. So, what, what was, can you tell me a bit more about some of the other missions you flew from Witchford?

GP: Well, I only did, I only did five operations from Witchford and I got frostbite, because we got attacked by a night fighter which destroyed all the communications and heating in the aircraft, but we managed to get back ok. So, that was alright and that was me put away from frostbite to Ely hospital for some time and then I was transferred to Waterbeach for recuperation and then I picked up another crew at Waterbeach which is Ted Cousins’s and I finished my tour of operations at Waterbeach with that crew.

BJ: What were you flying in at Waterbeach?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: What planes were you flying in from Waterbeach?

GP: Lancaster IIs.

BJ: Lancaster IIs. Ok, right, and can you tell me as what it was like on the base there, day to day life?

GP: Base was good because Witchford was a wartime place and everything was so dispersed you could walk miles for meals and things like that. But Waterbeach was a pre-war station and everything was on tap and there were nice billets and cosy, not like the Nissen huts that we did have, so these were brick-built, brick-built buildings and quite comfortable in a way.

BJ: And what did you do in your time off?

GP: Just going home [laughs].

BJ: Really? Aha.

GP: If you could get home. [unclear] the time off just mainly drinking [laughs].

BJ: What was it like coming home after being on operations?

GP: It was very strange and it’s a funny thing, I haven’t been away from home until I went in the Air Force. It’s a very strange feeling when you come back home and see that, it was a good feeling, but it didn’t last long so I had to go back again and that was it.

BJ: And what did you tell your mum and dad about your life in the RAF?

GP: I didn’t tell them anything, I didn’t think it was fair.

BJ: Ah.

GP: Because my brother, my brother was a navigator wireless operator on Mosquitoes, he was out in Burma so there’s both of us, there were three boys in the family and just my elder brother and myself were in the Air Force and the younger brother, he went in the army, just after the war. It was, it was quite strange because all your friends were away and we just had to nosy around, just going to the pictures or something like that. It wasn’t all that pleasant, it’s nice to see your family but as I say, it was quite boring.

BJ: And what sort of missions were you involved in, when you were at Waterbeach? Where were the targets?

GP: The targets, Witchford was, the targets were German targets, Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Augsburg and one or two others. From Waterbeach there was quite a variety of targets which are sometimes daylight raids and night raids, sometimes were French targets, and then all of a sudden you’d be onto a German target at night, which is [unclear] sorted it out.

BJ: What did you have a preference for daytime or nighttime missions?

GP: I used to like to rather go at night time, I didn’t like daytime [laughs]. You could see too much.

BJ: Right. Were there any particularly memorable missions that you flew on?

GP: Actually, most of them were quite memorable, we did a raid to Beckdiames which was in Southern France and that was an eight hour trip and this was a daylight raid and we went out at under a thousand feet all the way and until we got to the target, the target was a port actually and we climbed up to the bombing height, bombed and dropped down to, under a thousand feet again because of the radar, that was the idea of it but it was a long trip, it was an eight hour trip and it was quite a dangerous trip because the Bay of Biscay it was the, the Junkers 88 used to wonder around there quite a lot, you know, so. And then, there was another one which was to Stettin which was in Poland and that was another long trip, under a thousand feet all the way, this was a night time raid and we flew over Denmark and we could see the lights of Sweden and the anti-aircraft fire was coming up from Sweden, things like that [laughs] and then we went to, got to Stettin which we got to the bombing height and came back down again and what [unclear], we just lost one, one squadron, one aircraft on that squadron. So, and there was, there’s quite a few things which, one of the most scary attacks that we had was my last operation really to Duisburg. And that was the, the squadron went out early to bomb Duisburg, there was over a thousand aircraft to do it, and then, as soon as we got back, over the target the air was black with flak and it was the most frightening experience, I was in daylight did not expect to go to a German target in daylight and then it gradually settled down then but when we got back, we were sent down to, the air gunners were sent down to the bomb disposal place to help to load bombs up again for the same target and then the following day the German, the Americans bombed the same place, that was a disastrous place, terrible. That was about it, you know, but most of the trips were rather scary cause you never knew what was gonna happen there [unclear], you could be attacked by fighters any time.

BJ: What was it like being up in the turret?

GP: Very cold. Very cold [unclear] with ice all the way down there because we didn’t have any Perspex in the turret, we had it taken out because you can just imagine if you are flying at night and you can get attacked by a fighter and if you get any dirt on your Perspex you wouldn’t, it would be a, you wouldn’t know whether you got a fighter coming through, you see but where I got frostbite was around about forty degrees below but you see, your oxygen mask you had a lot of breath dripping down you know, froze up and all that.

BJ: What were you wearing to keep warm then?

GP: Well, I had a heated suit actually, the first time was one of these urban jackets and trousers which were all [unclear] and things like that. Eventually they got full heated suits which you’d plug into your boots and plug into your gloves, they heated up all over so you, you weren’t so cumbersome in the turret so, so that wasn’t too bad. It was when, the one time I said when the, the heating got shot up but it was cold.

BJ: Ok. And anything else that you remember about your time in the two squadrons?

GP: I’m just trying to think about it now. I was involved in athletics with the squadron so I did [unclear] got plenty of time off, things like that, apart from my flying, I was excused duties because I was, I got involved in football and things like that, I didn’t have to do any guard duties and things like that so.

BJ: Ok. Did that involve you going around to other bases?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: Did you go to other bases doing that?

GP: It was just the odd at lib sort of things, you know, you compete against the Americans or something like that, you know and,

BJ: Ok, how did you get on?

GP: We weren’t as good as the Americans, I tell you.

BJ: [laughs]

GP: No, we weren’t as good as the Americans, no, they got far greater facilities and that sort of things like that, you know.

BJ: Ok, and what did you do at the end of the war? What, you know, how did you get demobbed and that sort of thing?

GP: Well, when the, as I finished mature, I was sent up to a place in Northern Scotland, place called Bracla and that was for time expired men, aircrew you see, had [unclear] virtually offices and things like that, and my, my flight commander was up there as well, Lord Mackie, he ended up as Lord Mackie and we just had to march about and things like that and then we were selected for ordinary jobs in the Air Force you see and I wanted to become a PTI which is a Physical Training Instructor because I would’ve had the opportunity to go through to Loughborough and take sports right the way through and then that’s what I wanted to go for but they put me down as a driver [laughs]. So I moved from there and went to driving school at Weeton in Blackpool which was quite good actually, it was quite enjoyable and then from then I was, I went to various camps in this country and then my final camp was in Germany where I was with a microfilm unit taking microfilm documents of all the machine tool drawings and things like that and that’s,

BJ: Where was that?

GP: That was at Frankfurt, Frankfurt but we wondered around Stuttgart and other places, went round all these factories and taking these microfilms of these documents and things like that, that was the, that was my end, I ended and came back to Weeton where I was demobbed.

BJ: So, what was it like being in Germany, down on the ground, this time?

GP: It was, it wasn’t too bad, we weren’t allowed to fraternise at all, you know, we did play football against the Germans and things like that and got thrushed.

BJ: Oh, alright [laughs]

GP: So, I played for the army when we were in Frankfurt and we played a game against the Germans, select team which is if we really got thrushed and that was the first time we realised what sort of football the continentals played as compared with our football but anyway that was, I enjoyed my time in Germany and I learned to speak German quite fluently and which stood me in good sted with my civilian job so that was good and

BJ: How did you learn to speak German?

GP: Well, I had to speak German [laughs].

BJ: Yeah?

GP: Well, I mean, if you were driving around and things like that and you lost your way, you had to talk and things like that so that’s how it went [unclear] I wish I had kept it up actually, which it would have been useful to me but it was useful anyway because I dealt with the Germans, a German company in me civilian life more so than anything and of course was a strange thing that the fellow that I dealt with in Germany, he was a Luftwaffe pilot [unclear] [laughs] and something I know quite well actually.

BJ: Did you tell him you’d been in the RAF?

GP: Yes, yeah. So, I mean it was no end to the, not at all, not with service people [unclear] so they got a job to do, we got a job to do and that was it but

BJ: So what did you do after you were demobbed then?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: What did you do after the RAF? After you left?

GP: I went back to my old company and I gradually progressed there, we were manufacturing cars, Standard, the Triumph and the Triumph Spitfires and these sort of things, and but there was so much, so many problems down in the Midlands with the car industry of strikes and all that sort of thing and I just got married and we bought a new house and things like that, it’s becoming very difficult because we’re going on short time, even when you’re on staff you’re on short time so, I decided to make a move and come up here and that was that.

BJ: What did you do up here, in Scotland?

GP: I ended up as a production director at Carron company in Falkirk and but I set up a, came up and set up a plant for manufacturing steel bars and that sort of thing and then I did twenty-three years there and that’s it.

BJ: Ok, and how do you think being in Bomber Command affected the rest of your life?

GP: It did affect me because the, the people, the people that you met in Bomber Command, they were virtually like your brothers, a wonderful set up, it was great and as I say, it was still, we’re still getting involved with reunions and one of the addresses, the two addresses that I gave you, these are the people that I flew with, so, it was, I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Really.

BJ: Ok. Alright, anything else you’d like to add, Mr. Payne?

GP: No, I don’t think so. I think that’s about all, that’s, I summarised quite a bit.

BJ: Alright. Thank you very much.

GP: Ok, thank you. [file continued] I’m trying to fill it all in you, you can’t.

US: I know you can’t [unclear], I just.

BJ: Right, this is the interview with Mr. Payne continuing.

GP: Right, one of the most horrendous trips that I did was to Frankfurt. And after the target, we were coming back, we were about half an hour away back from the target when I spotted a aircraft with about four hundred meters behind below and it turned out to be a Messerschmitt 109 and I wanted, I tried to warn the, I tried to warn the pilot but the intercom had frozen up, my mouthpiece had frozen up and I tried to Morse coding with the emergency light and the emergency light wasn’t working so that was it, there was actually nothing I could do about it and as the aircraft came closer to me, which was below at about a hundred meters, I opened fire on it and the guns jammed so therefore I was completely at a loss, I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t warn the captain or anything about cause I’ve no intercom and no emergency lighting so I just had to hang on a bit and then after a minute the aircraft came underneath us and opened fire and blasted all the centre of the aircraft and the smell of cordite was amazing and then the aircraft started to manoeuvre all over the sky doing very violent evasive action or I thought that we were out of control, completely out of control so I got out of my turret and walked back and found that the main door was swinging open and then I got up to the mid upper turret and the mid upper gunner had gone, he’d bailed out and there was all cannon shell holes all around his turret there, so eventually I thought, that so quiet I thought the rest of the crew had gone, now I walked up, gradually I got through into the main cabin and found the rest of the crew were ok and so forth and that we went back to the sit in the turret, well, I couldn’t do anything anyway, so we were coming in to land, but we got back home ok, coming in to land and I started to smell cordite and I, I looked about at the back in the, in the ammunition panniers and there was a fire in there which must have got hit by an incendiary bullet and we had to land, emergency land and it was, it was an incendiary bullet, that was wedged in the bullets, so [laughs], that was that day but there was also another one, no, I don’t think I will talk about that, just [unclear].

BJ: Ok, thank you.

GP: Well, my life was a bit raggedy, I was an apprentice to Sheet Metal Work and worked in a company in the centre of Birmingham and we were manufacturing spats for Lysander aircraft and making fire pumps, things like that and more interested in sports than anything else [laughs].

BJ: And how did you come to join the RAF?

GP: Well, I joined the Air Training Corps, which I was one of the original members and it was the Air Training Corps was at Birmingham was the Austin Motor Company Squadron which was 480 and 479, there were two squadrons in the, ATC squadrons, and that’s why I started to get involved with the, with the Air Force, thinking a lot about the Air Force at the time. We went to camp to RAF Weeton, which was a Pathfinder Squadron, 7 Squadron, which were flying Stirlings and the most funniest part about us, we wanted to go into St Yves for the evening and we had to know a password to go out of the place because there was operations on that night and they said the password was WATER, which was this, I think they were pulling our legs or something like that, they said because the Germans can’t sound the w’s is wasser, so that was the sort of thing, that gave me a great interest in the Air Force.

BJ: OK. And when did you come to join the Air Force?

GP: I joined when I was seventeen and a half and I went to Vishyde Close in Birmingham to get assessed and I was assessed as a pilot and I was given a number and then sent back to work again because they wouldn’t call me up until I was eighteen but in the meantime I had a letter from them saying that it would possibly take far too long for me to become a pilot and that they’d had other vacancies in the Air Force which was an air gunner so I decided to do that.

BJ: And what year was this?

GP: 1943, yes.

BJ: And what happened when you started with the RAF?

GP: What happened?

BJ: Yes, what did your training involve?

GP: The training, we went to London, to Lord’s Cricket Ground and then we were put into high-rise flats and then we had our meals at the London zoo and used to march there every, for breakfast those [unclear] and tea and there’s one occasion there when there was a heavy air raid and at Lord’s Cricket Ground there’s the Regent’s Park and [unclear] anti-aircraft comes and we had to move out and go to another set of flats which was a hospital, which the RAF hospital, and carry all the patients down from the high floors cause they wouldn’t, couldn’t go down in the lifts and carry the, down in stretchers into the basement and back up then and then after that initial training, I went to Bridlington for ITW and that’s a nice seaside place, enjoyed it there and then off we went to Air Gunners School which was in the Isle of Man, just outside Ramsey, a place called Andreas and then, after three months of training, we were sent to an ITW, which was in Banbury where we were crewed up and flew in Wellingtons and from then we, we had to go to Heavy Conversion Unit which was a Stirling set-up, a place called Wratting Common in Cambridgeshire and we did that and then also we moved to, did an escape course at Feltwell and which was hilarious and then.

BJ: What did they teach you there about escaping?

GP: Unarmed combat and this sort of thing but it was, it just became a laugh actually [laughs] so, but we were there for the week and then we went back onto Wratting Common on Stirlings but at that time the Stirlings was being phased out from operations in the, for the main force in Bomber Command and we were transferred to, onto Lancasters which were radial engines Mark II, Hercules engines and from then we did a couple of weeks training there before we were put onto the squadron.

BJ: How did you find the Lancasters compared to the Stirlings?

GP: I didn’t like the Stirlings at all.

BJ: Ah!

GP: No, they frightened me because whilst I was converting onto Stirlings, I had to go to Newmarket to do a short gunnery course there and in the meantime my crew then crashed one of the Stirlings at [unclear] market so and but I, they phased these Stirlings out and that’s why I went on to Lancasters and then from Lancasters on Waterbeach we moved to a squadron which was RAF Witchford.

BJ: Ok. What happened when you got to Witchford?

GP: [laughs] We arrived at Witchford and then the following day we had to go round, signing in, which is a normal thing, you go to all the various sections and sign in and so forth like that and you get your billets and that and I went to the gunnery leaders office to sign in there and he says, ah yes, he says, you’re on tonight and that was the second day I was there [laughs] and I was, I said, what for? He says, well, there’s a rear gunner taken ill and you’ll have to, you’ll be flying with Lieutenant Speelenburg who was South African.

BJ: How did you feel about that?

GP: Terrible, it was, it was, to do a first op with a sprog crew which, the crew was a, they hadn’t done any operations before anyway and I hadn’t done any operations so they obviously bloodied with a new crew and that was one of the most horrendous air raids I’ve been on and that was to Augsburg, in southern Germany which was an eight hour journey, it was the most frightening experience I’ve ever had in my life so.

BJ: What happened on the mission?

GP: Oh, we got attacked over the target by a, by two Messerschmitt 109s, well, we got through that alright but it was, I never in my life would have expected to witness such a melee which was over the target, and I thought to myself I’m not coming out through this loss.

BJ: Do you remember what the target was?

GP: Augsburg.

BJ: Yes.

GP: It was the MAN works.

BJ: Ok.

GP: So that was, it was a night trip, eight-hour trip.

BJ: And did you stay with that crew then after?

GP: No, no.

BJ: No. So, how did you get assigned to a crew?

GP: I’d already got my crew,

BJ: Oh, ok.

GP: From, from Banbury, from Chipping Warden. I’d already got my crew, my crew were there but they were doing cross country south. So that was me doing me first op and I thought, I’ll never gonna get through this. So, that was my first operation and in the morning I couldn’t get off to sleep so I decided to, I walked into Ely and the Oxford and Cambridge boat race was on there so that was the, because they didn’t have the boat races in London because of the bombings, so I saw the boat race there.

BJ: Oh, ok.

GP: And came back, that’s it, so I said, no, that’s it, you can’t, you got to, maybe get through this alright but just forget about it and take it as it comes.

BJ: Ok. So, what, what was, can you tell me a bit more about some of the other missions you flew from Witchford?

GP: Well, I only did, I only did five operations from Witchford and I got frostbite, because we got attacked by a night fighter which destroyed all the communications and heating in the aircraft, but we managed to get back ok. So, that was alright and that was me put away from frostbite to Ely hospital for some time and then I was transferred to Waterbeach for recuperation and then I picked up another crew at Waterbeach which is Ted Cousins’s and I finished my tour of operations at Waterbeach with that crew.

BJ: What were you flying in at Waterbeach?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: What planes were you flying in from Waterbeach?

GP: Lancaster IIs.

BJ: Lancaster IIs. Ok, right, and can you tell me as what it was like on the base there, day to day life?

GP: Base was good because Witchford was a wartime place and everything was so dispersed you could walk miles for meals and things like that. But Waterbeach was a pre-war station and everything was on tap and there were nice billets and cosy, not like the Nissen huts that we did have, so these were brick-built, brick-built buildings and quite comfortable in a way.

BJ: And what did you do in your time off?

GP: Just going home [laughs].

BJ: Really? Aha.

GP: If you could get home. [unclear] the time off just mainly drinking [laughs].

BJ: What was it like coming home after being on operations?

GP: It was very strange and it’s a funny thing, I haven’t been away from home until I went in the Air Force. It’s a very strange feeling when you come back home and see that, it was a good feeling, but it didn’t last long so I had to go back again and that was it.

BJ: And what did you tell your mum and dad about your life in the RAF?

GP: I didn’t tell them anything, I didn’t think it was fair.

BJ: Ah.

GP: Because my brother, my brother was a navigator wireless operator on Mosquitoes, he was out in Burma so there’s both of us, there were three boys in the family and just my elder brother and myself were in the Air Force and the younger brother, he went in the army, just after the war. It was, it was quite strange because all your friends were away and we just had to nosy around, just going to the pictures or something like that. It wasn’t all that pleasant, it’s nice to see your family but as I say, it was quite boring.

BJ: And what sort of missions were you involved in, when you were at Waterbeach? Where were the targets?

GP: The targets, Witchford was, the targets were German targets, Stuttgart, Frankfurt and Augsburg and one or two others. From Waterbeach there was quite a variety of targets which are sometimes daylight raids and night raids, sometimes were French targets, and then all of a sudden you’d be onto a German target at night, which is [unclear] sorted it out.

BJ: What did you have a preference for daytime or nighttime missions?

GP: I used to like to rather go at night time, I didn’t like daytime [laughs]. You could see too much.

BJ: Right. Were there any particularly memorable missions that you flew on?

GP: Actually, most of them were quite memorable, we did a raid to Beckdiames which was in Southern France and that was an eight hour trip and this was a daylight raid and we went out at under a thousand feet all the way and until we got to the target, the target was a port actually and we climbed up to the bombing height, bombed and dropped down to, under a thousand feet again because of the radar, that was the idea of it but it was a long trip, it was an eight hour trip and it was quite a dangerous trip because the Bay of Biscay it was the, the Junkers 88 used to wonder around there quite a lot, you know, so. And then, there was another one which was to Stettin which was in Poland and that was another long trip, under a thousand feet all the way, this was a night time raid and we flew over Denmark and we could see the lights of Sweden and the anti-aircraft fire was coming up from Sweden, things like that [laughs] and then we went to, got to Stettin which we got to the bombing height and came back down again and what [unclear], we just lost one, one squadron, one aircraft on that squadron. So, and there was, there’s quite a few things which, one of the most scary attacks that we had was my last operation really to Duisburg. And that was the, the squadron went out early to bomb Duisburg, there was over a thousand aircraft to do it, and then, as soon as we got back, over the target the air was black with flak and it was the most frightening experience, I was in daylight did not expect to go to a German target in daylight and then it gradually settled down then but when we got back, we were sent down to, the air gunners were sent down to the bomb disposal place to help to load bombs up again for the same target and then the following day the German, the Americans bombed the same place, that was a disastrous place, terrible. That was about it, you know, but most of the trips were rather scary cause you never knew what was gonna happen there [unclear], you could be attacked by fighters any time.

BJ: What was it like being up in the turret?

GP: Very cold. Very cold [unclear] with ice all the way down there because we didn’t have any Perspex in the turret, we had it taken out because you can just imagine if you are flying at night and you can get attacked by a fighter and if you get any dirt on your Perspex you wouldn’t, it would be a, you wouldn’t know whether you got a fighter coming through, you see but where I got frostbite was around about forty degrees below but you see, your oxygen mask you had a lot of breath dripping down you know, froze up and all that.

BJ: What were you wearing to keep warm then?

GP: Well, I had a heated suit actually, the first time was one of these urban jackets and trousers which were all [unclear] and things like that. Eventually they got full heated suits which you’d plug into your boots and plug into your gloves, they heated up all over so you, you weren’t so cumbersome in the turret so, so that wasn’t too bad. It was when, the one time I said when the, the heating got shot up but it was cold.

BJ: Ok. And anything else that you remember about your time in the two squadrons?

GP: I’m just trying to think about it now. I was involved in athletics with the squadron so I did [unclear] got plenty of time off, things like that, apart from my flying, I was excused duties because I was, I got involved in football and things like that, I didn’t have to do any guard duties and things like that so.

BJ: Ok. Did that involve you going around to other bases?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: Did you go to other bases doing that?

GP: It was just the odd at lib sort of things, you know, you compete against the Americans or something like that, you know and,

BJ: Ok, how did you get on?

GP: We weren’t as good as the Americans, I tell you.

BJ: [laughs]

GP: No, we weren’t as good as the Americans, no, they got far greater facilities and that sort of things like that, you know.

BJ: Ok, and what did you do at the end of the war? What, you know, how did you get demobbed and that sort of thing?

GP: Well, when the, as I finished mature, I was sent up to a place in Northern Scotland, place called Bracla and that was for time expired men, aircrew you see, had [unclear] virtually offices and things like that, and my, my flight commander was up there as well, Lord Mackie, he ended up as Lord Mackie and we just had to march about and things like that and then we were selected for ordinary jobs in the Air Force you see and I wanted to become a PTI which is a Physical Training Instructor because I would’ve had the opportunity to go through to Loughborough and take sports right the way through and then that’s what I wanted to go for but they put me down as a driver [laughs]. So I moved from there and went to driving school at Weeton in Blackpool which was quite good actually, it was quite enjoyable and then from then I was, I went to various camps in this country and then my final camp was in Germany where I was with a microfilm unit taking microfilm documents of all the machine tool drawings and things like that and that’s,

BJ: Where was that?

GP: That was at Frankfurt, Frankfurt but we wondered around Stuttgart and other places, went round all these factories and taking these microfilms of these documents and things like that, that was the, that was my end, I ended and came back to Weeton where I was demobbed.

BJ: So, what was it like being in Germany, down on the ground, this time?

GP: It was, it wasn’t too bad, we weren’t allowed to fraternise at all, you know, we did play football against the Germans and things like that and got thrushed.

BJ: Oh, alright [laughs]

GP: So, I played for the army when we were in Frankfurt and we played a game against the Germans, select team which is if we really got thrushed and that was the first time we realised what sort of football the continentals played as compared with our football but anyway that was, I enjoyed my time in Germany and I learned to speak German quite fluently and which stood me in good sted with my civilian job so that was good and

BJ: How did you learn to speak German?

GP: Well, I had to speak German [laughs].

BJ: Yeah?

GP: Well, I mean, if you were driving around and things like that and you lost your way, you had to talk and things like that so that’s how it went [unclear] I wish I had kept it up actually, which it would have been useful to me but it was useful anyway because I dealt with the Germans, a German company in me civilian life more so than anything and of course was a strange thing that the fellow that I dealt with in Germany, he was a Luftwaffe pilot [unclear] [laughs] and something I know quite well actually.

BJ: Did you tell him you’d been in the RAF?

GP: Yes, yeah. So, I mean it was no end to the, not at all, not with service people [unclear] so they got a job to do, we got a job to do and that was it but

BJ: So what did you do after you were demobbed then?

GP: Sorry?

BJ: What did you do after the RAF? After you left?

GP: I went back to my old company and I gradually progressed there, we were manufacturing cars, Standard, the Triumph and the Triumph Spitfires and these sort of things, and but there was so much, so many problems down in the Midlands with the car industry of strikes and all that sort of thing and I just got married and we bought a new house and things like that, it’s becoming very difficult because we’re going on short time, even when you’re on staff you’re on short time so, I decided to make a move and come up here and that was that.

BJ: What did you do up here, in Scotland?

GP: I ended up as a production director at Carron company in Falkirk and but I set up a, came up and set up a plant for manufacturing steel bars and that sort of thing and then I did twenty-three years there and that’s it.

BJ: Ok, and how do you think being in Bomber Command affected the rest of your life?

GP: It did affect me because the, the people, the people that you met in Bomber Command, they were virtually like your brothers, a wonderful set up, it was great and as I say, it was still, we’re still getting involved with reunions and one of the addresses, the two addresses that I gave you, these are the people that I flew with, so, it was, I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Really.

BJ: Ok. Alright, anything else you’d like to add, Mr. Payne?

GP: No, I don’t think so. I think that’s about all, that’s, I summarised quite a bit.

BJ: Alright. Thank you very much.

GP: Ok, thank you. [file continued] I’m trying to fill it all in you, you can’t.

US: I know you can’t [unclear], I just.

BJ: Right, this is the interview with Mr. Payne continuing.

GP: Right, one of the most horrendous trips that I did was to Frankfurt. And after the target, we were coming back, we were about half an hour away back from the target when I spotted a aircraft with about four hundred meters behind below and it turned out to be a Messerschmitt 109 and I wanted, I tried to warn the, I tried to warn the pilot but the intercom had frozen up, my mouthpiece had frozen up and I tried to Morse coding with the emergency light and the emergency light wasn’t working so that was it, there was actually nothing I could do about it and as the aircraft came closer to me, which was below at about a hundred meters, I opened fire on it and the guns jammed so therefore I was completely at a loss, I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t warn the captain or anything about cause I’ve no intercom and no emergency lighting so I just had to hang on a bit and then after a minute the aircraft came underneath us and opened fire and blasted all the centre of the aircraft and the smell of cordite was amazing and then the aircraft started to manoeuvre all over the sky doing very violent evasive action or I thought that we were out of control, completely out of control so I got out of my turret and walked back and found that the main door was swinging open and then I got up to the mid upper turret and the mid upper gunner had gone, he’d bailed out and there was all cannon shell holes all around his turret there, so eventually I thought, that so quiet I thought the rest of the crew had gone, now I walked up, gradually I got through into the main cabin and found the rest of the crew were ok and so forth and that we went back to the sit in the turret, well, I couldn’t do anything anyway, so we were coming in to land, but we got back home ok, coming in to land and I started to smell cordite and I, I looked about at the back in the, in the ammunition panniers and there was a fire in there which must have got hit by an incendiary bullet and we had to land, emergency land and it was, it was an incendiary bullet, that was wedged in the bullets, so [laughs], that was that day but there was also another one, no, I don’t think I will talk about that, just [unclear].

BJ: Ok, thank you.

Collection

Citation

Brenda Jones, “Interview with Geoff Payne,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 22, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/11522.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.