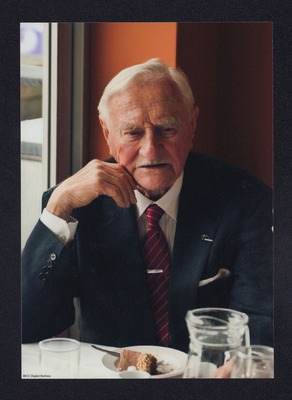

Interview with Andrzej Jeziorski

Title

Interview with Andrzej Jeziorski

Description

Andrzej Jeziorski was born in Poland and, when war broke out, fled to Britain, where he flew as a pilot with 304 Squadron. He specifially recalls 1st September 1939. He talks about his father, a Navy officer who served in the First World War and mentions his first contact with the Air Force when he and his family moved to Deblin. Andrzej tells of his escape from Poland to France, his further education there and his evacuation to Britain. Initially, he was posted to Scotland and trained to join the 16th Tank Brigade. He then decided to transfer to the Air Force and, in 1942, started training as a pilot. He was posted to 304 Squadron on various stations. Andrzej tells of his career in civilian aviation after the war: operating flights all over the world for Skyways and Britannia, until his retirement in 1982. He talks about his life in Britain during the war and mentions various episodes including being taught English by university lecturers and socialising with them. Andrzej tells of being assigned to go on patrols, locating and attacking enemy submarines and expresses his views on Poland’s situation after the war. He talks about the Polish Air Force Association in Britain, his involvement in it and the memorials to Polish aircrews.

Creator

Date

2017-07-05

Spatial Coverage

Coverage

Type

Format

01:19:38 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

AJeziorskiAFK170705

Transcription

CB: My name is Chris Brockbank and today is the 5th of July 2017 and it’s half past twelve and I am in Chiswick, Grove Park with Andrzej Jeziorski to talk about his time in the RAF and experiences of getting to Britain. So, what are the earliest recollections you have of life?

AJ: Well, I was, as I said, I was born in Warsaw and first few years I, we lived near Gdansk, in Sopot because my father was an officer in the Polish Navy. My father served during the First World War in the Navy but shortly after I was born, he transferred to the Air Force and he reached rank of Colonel eventually. We, initially we stayed in Sopot in Gdansk then we moved to Warsaw and shortly after that my father was sent to Paris for two years to Ecole Superior [unclear] for further technical studies, he was actually diploma engineer and he was sent there for further studies on airline engines and airframes. On return to Poland, we, my father was initially posted to Deblin, which is the Polish Air Force Academy and we stayed there for four years, that was my sort of first contact with the Air Force. We returned to Warsaw in, round about 1930-31 and I commenced schooling in Warsaw, in Poniatowski Gymnasium [laughs] but that’s not very important. And I, and we stayed in, lived in Warsaw until the outbreak of war, in fact I remember in 1939 I returned from the summer holiday on the 28th of August 1939 and I was getting ready to go back to school when in the morning of the 1st of September I was awakened by the gunfire and sirens. I ran into the garden and I saw the formation of German bombers surrounded by the puffs of explosion from the anti-aircraft guns and that was it, that was the beginning of the war. And my father was recalled back to [unclear], he was already retired and worked as engineer in the [unclear] aviation factory in Warsaw but he was recalled back to service and he was posted to South-Eastern Poland with a group of officers to receive the aircraft that was sent from Britain via Constanta, unfortunately the aircraft only reached Constanta harbour and they were never offloaded because of the advance of, very quick advance of the German forces. Aircraft were Fairey Battle, even that all, that useful to Poland because it was a light bomber, really, and we needed fighters but neither France or Britain could provide fighters, they were rather short themselves. Anyhow, we, my mother on the 5th of September, my mother decided that we follow our father to Lviv, to South-eastern Poland and we left Warsaw for Lviv and we stayed in Lviv for several days and on the 17th of September when Russia attacked Poland we travelled across the border to Romania where we re-joined my father in Romania, he was already across the border. We stayed in Romania for about a month I think and then we travelled via Yugoslavia, Italy [unclear] to Paris, to France. Initially I was a little bit too young to join the forces, so I went back to lycée, back to school. It was a Polish Lycée that existed in Paris for many years before the war. Anyway, I started my school again in Paris. In, one [unclear], I completed the first year of study, was actually lycée for last two years before matriculation. When offensive started, German offensive started, my father agreed that I would join the Army and I was, I passed my, all the tests in Paris and the interviews and I was posted to cadet officer’s school near Orange, I think the name was Bollene but I am not sure, don’t quote me that, I only managed to reach Bollene when France collapsed and school was evacuated via Saint-Jean-de-Luz and to Plymouth and from Plymouth up to Scotland to Crawford in Scotland. In Scotland we continued our training very quickly, it was amazing how quickly everything was organised, initially we were issued with infantry armament but shortly after that [unclear] carriers arrived and Valentine tanks and we trained, completed our training by November 1940, we completed our training and I was made the cadet officer, corporal cadet officer [laughs]. The, shortly after I completed my training, the Polish forces decided that, to be an officer, I must get my matriculation, in other words pass my what is the A level exam the Matura [laughs]. So, I was posted back to the same school that I was in France, that school was evacuated as well to England, to Scotland and it was in Dunalastair House near Pitlochry in Perthshire, very beautiful place [laughs]. Anyway, I was sort of released from the, for six months, from the forces to complete my study and pass my matriculation, well, I only had six months, it was difficult, but I managed and I managed to pass all the exams and I went back to the tank corps, it was 16 Tank Brigade number 2 Battalion of tank corp. Round about that time, I decided that I must try to transfer to the Air Force and I started to applying to be transferred to the Air Force, explaining that I have sort of family links with the Air Force [laughs] and I asked them to consider this and transfer me to the Air Force. Eventually, I managed [laughs] and in beginning of 1942 I commenced my training as a pilot. Training initially was four months of ground training in preparation for flying, then, after short leave, initial flying in Hucknall near Nottingham and from there another four months service flying school at Newton, also near Nottingham. I completed my training, I obtained my wings, and also I obtained my commission [laughs], which was organised [laughs] and I was posted to RAF Manby, which was the first Air Armament School, it’s half, about half way between Peterborough and Grimsby, a line between Peterborough and

CB: It’s in Lincolnshire, yes

AJ: RAF Manby

CB: Manby

AJ: First Air Armament School, pre-war station, the station commander was Group Captain Ivens, First World War pilot, rather severe but we [unclear] [laughs] and [unclear], he had certain sympathy towards us and he was a good station [unclear] and we spend many months flying there and I was flying as a staff pilot, flying Blenheims IV and Blenheim I on mainly bombing training. Well, after many months of that, I was suddenly posted to Squires Gate to a general reconnaissance course which meant that I will be posted to Coastal Command because it was mainly navigation training for flying over the sea. It was just over two months course, rather severe but that course helped me a lot in the future because I obtained second class navigation warrant and that helped me in obtaining my licence later on, civvy licence. Eventually, after completion of training in Squires Gate, I was posted to the squadron, which was based in Chivenor and I started flying as a second pilot. Initially, one had to do at least ten, sometimes more flights as a second pilot before being posted to Operational Training Unit to pick up his own crew. Well, I did my ten operations mainly flying over the Atlantic. The flying was consist of patrols, long ones lasted, patrols lasted for over ten hours, we had special additional fuel tanks in bomb bays, apart from depth charges, aircrafts was Wellington XIV, especially designed for operations in Coastal Command, it was equipped with ASV, Aircraft-to-Surface Vessel which was, although it was a primitive radar, it was a very good radar, we could pick up contacts distance over one hundred and twenty miles, that if contact was large enough [laughs], it was, flying was tiring but I found rather interesting it, weather was not in favour of us particularly when we were based up north in Benbecula the weather was our greatest enemy, flying sometimes in very terrible conditions over the Atlantic and several times we had to be diverted to different fields because weather was closing on, closing the fields on the west coast of Scotland so we had to be posted sometimes to Northern Ireland to Limavady. It was interesting and eventually I was posted to Operational Training Unit to Silloth, RAF Silloth that was 6 OTU Coastal Command to pick up my own crew. We completed our training there, we were posted back to squadron and just as we completed initial sort of training with the squadron, war ended and that was the end of my war, but the squadron was posted to Transport Command and I was posted to Crosby-on-Eden Transport Command Conversion Unit, it was a tough three months course for pilots, getting them ready for operation in Transport Command, it was tough course but again that course helped me in obtaining my civvy licences later on. In, on return from, unfortunately I was due to go to India with my crew, getting ready to be posted to India but unfortunately my navigator failed the last of overseas medical, they discovered that he suffering from anginal heart and I lost my navigator and because of that I was posted back to the squadron, 304 Squadron, which in the meantime, was operating as Transport Squadron from Chedburgh, and that was the squadron operated Warwicks, sort of large Wellington [laughs] transport plane, and operating mainly to Athens with [unclear], we operated via east, Pomigliano near Naples and then Athens and back again [laughs]. And I stayed with the squadron until the end of the existence of Polish Air Force and we were all transferred to Polish resettlement call but I decided to continue flying and I was posted to [unclear] Navigation School and I flew Wellingtons, Wellington X, from Royal Air Force Topcliffe in Yorkshire and I was there for about a year and a half until I was asked to relinquish my commission and I went back to civil life, civilian life, but, as I said, I managed to complete two very important courses in RAF and that helped me quite a bit in passing the exams for airline transport pilot licence. And I, in possibly 1948 when I commenced my flying in civil aviation. Initially, my first employment was in, up in Blackpool and I operated Rapid aircrafts, De Havilland Rapide over the Irish Sea from Blackpool to Ronaldsway and to Dublin and Belfast and Glasgow, for about, for a whole year I was operating over the Irish Sea for Lancashire Aircraft Corporation, that was the firm I was employed with, Lancashire Aircraft Corporation. Lancashire Aircraft Corporation later changed name to Skyways and I stayed with the firm and I was, after a year in Blackpool, I was moved to Bovingdon to join the crew of captain Raymond, very good pilot, to operate Haltons, a transport plane, Halton was a civil version of Halifax 8 C and we used to operate freighting services to, well, yes, we used to fly everywhere, to the Far East, to Singapore, to Island of Mauritius [laughs] on the Indian Ocean, to the, all around the Middle East and but in about, after about a year operating with, flying with Captain Raymond we had a rather, in fact very unpleasant incident. We were due to take eight tons of optical instruments, four tons from UK and then four tons from Hamburg and operate to Hong Kong. We took off early in the morning, must have been seven o’clock in the morning, beautiful day, we climbed to our cruising altitude which, as far as I remember, was nine thousand feet, and I just went down to my navigation cabin to start my navigation, I obtained first pinpoint I remember at [unclear], I’ve written it on my logbook, when fire bell rang. I rushed back to the cockpit and I saw the number one engine on fire, it was not only fire but black smoke, we turned back towards Bovingdon but just at that time, just looking at that engine when the whole engine separated, the engine cracked in second row of cylinders, just cracked, and propeller, reduction gear, cowlings and front part of the engine just separated and took fire [unclear], and propeller just sort of twisted right and hit the leading edge of the aircraft, between the engines and cut through the leading edge and through the oil tank of number one, number two engine and a few moments later engineer had to stop number two engine because of lack, he was losing oil. Anyway, we were still at about eight thousand feet and we flew towards Bovingdon, Bovingdon also of course helping us with QDMs etcetera, help passing all the weather information etcetera and weather, as I said, was absolutely perfect, I could see Bovingdon from great distance I could see the runway and captain Raymond decided that we would land crosswind on as long runway accept crosswind was about ten knots and land direct on a long runway and we made a superb approach, or actually captain Raymond did [laughs] and we landed safely in Bovingdon. The aircraft looked terrible. One engine gone, one engine feathered, the aircraft covered with oil and dirty smoke [laughs], remnants looked absolutely terrible but would you believe, the engineer managed to fix it in three days, they replaced the engine, replaced the tank, replaced the leading edge and three days later aircraft operated to Milan. It was almost unbelievable [laughs]. But anyway, great work on British engineers [laughs]. So that was a rather unpleasant beginning of my long service with civil aviation, would you like me to continue?

CB. We’ll stop just for a minute.

AJ: Sorry?

CB: We’ll stop just for a moment. So, we are talking about Skyways and the incident with captain Raymond,

AJ: Yes

CB: But after that you got, what happened to you, you got your own command?

AJ: After that I started flying as a captain, we converted from Haltons to Avro York. I don’t know if you know the aircraft

CB: I know

AJ: [unclear]

CB: The Lancaster

AJ: And we started to operate mainly to the Middle East

CB: Right

AJ: Mainly to a place called Fayid in Canal Zone, that was of course in military zone of Canal Zone and civilian planes were not allowed to land there because of agreement between Egypt and UK, that only military planes would be landing on Canal Zone so we were all given a complementary commission between Malta and Fayid we operated as RAF crews on RAF markings and everything, we were back in uniform for a little while. The operation to the, there was always something happening when we were there, I remember first sort of international problem was the Iran, the, Mr Mosaddegh trying to get Abadan

CB: The oil field

AJ: [unclear] Abadan

CB: Yes

AJ: So we were all put up in uniforms and transferred to Castle Benito in Libya, later Castle Idris, artillery was loaded on our aircraft and we were all ready to occupy Abadan [laughs] but fortunately nothing happened, Shah returned to Iran and don’t know what’s happened to Mr Mosaddegh, but anyway he disappeared. So that was the first sort of international incident that I have seen and the next one of course was Suez, that was during the premiership of Mr Eden when Nasser, President Nasser decided to nationalise Suez Canal and of course there was a war between Israel and Egypt and Israel occupied Sinai peninsula and we were also involved, immediately involved in transferring flying troops not only to Cyprus to reinforce the Polish British base, there but also to other parts where there was a danger to the British [unclear] in Bahrein, Aden we had to fly troops there, also we had to evacuate British personnel from Castle Benito because of the danger in revolt in Tripoli. There was of course a big row between United States on one part and France and UK on the other but anyway everything slowly settled down and we started to operate via Cyprus to the Far East, mainly on trooping contract again. Cyprus was very pleasant place initially after the war as far as I remember, but slowly EOKA started to operate and things started to get really nasty, well, in fact, we lost one aircraft, EOKA managed to plot to put bomb on, in the gallery of one of our aircraft departing from Nicosia to UK with RAF families. The captain on that flight was I remember captain Cole and they were travelling from the hotel in Kyrenia via through the Kyrenia Mountains they had a puncture and the wheel was damaged, anyway they were delayed about forty five, fifty minutes to arrive at the airport, they were of course in a hurry, immediately [unclear] ran to the aircraft to distribute pillows and get cabin ready for the families to join the aircraft and the engineer was on a wing and captain, captain Cole and his first officer were walking towards the aircraft from the control tower, they were about half way, when bomb exploded in the gallery. The aircraft was immediately on fire, but it was a Sunday, was it Sunday? No, it was, only day but lunchtime and everything was quiet on the airfield, just one aircraft getting ready to departure was our aircraft, well, I mean, firm aircraft not mine [laughs], and the fire tender and all the emergency equipment parked near control tower, they didn’t expect anything, it was a very hot day and the crew of fire tenders had sort of undone their buttons and they were sort of sunning themselves and they didn’t notice that bomb exploded, was just [mimics a detonation] was a very small, small bomb and of course the captain, first officer noticed that, there were explosions and they started to run towards control tower to tell, to call the fire and the controller didn’t know, he was looking at them and sort of, he went on the balcony, he said, what? Aircraft on fire. So he ran back, pressed the button alarm but by the time fire tender alarm, the aircraft was gone

CB: Completely

AJ: Lost an aircraft. No one was hurt, the engine, when bomb exploded this engineer was on a wing, he almost fell off the wing but he didn’t [laughs] fortunately, girls were distributing pills in the cabin so they ran out of the cabin, no one was hurt but aircraft was lost. If you visit Nicosia, visit the museum, there was, there is a place, commemorating EOKA activities and there is a photograph of that aircraft, EOKA sort of proud that they managed to destroy one aircraft but they nearly, the aircraft was, the bomb was so timed to explode at the top of climb, had it not been for the puncture of the car bringing the crew from Kyrenia, the aircraft would have been at top of climb and that would have been it, six, over sixty RAF families, women and children were due to fly back to UK, that was one of the things that

CB: Fascinating, yeah

AJ: I still remember. The, after that, we, after that incident we started to operate trooping contracts to Far East, mainly to Singapore. We changed aircraft from Hermes to Lockheed 749s Constellation and of course it was much beautiful aircraft, lovely aircraft to fly and we initially started operating with troops to the Far East, to Singapore but later this changed into the freighting contract for BOAC to the Far East, that’s operating freight from UK to Hong Kong and to Singapore and I was posted for two years to New Delhi to operate the sector between New Delhi and Hong Kong and Singapore. It was interesting posting, India is an interesting place and it was lovely flying, one week of flying, one flight to Singapore, one flight to Hong Kong in a week and then a week off [laughs], rather pleasant and it was, generally speaking, I remember that as a very pleasant, very pleasant stay in India. As [unclear], when I returned from India, the Skyways decided to finish the operation and all the aircraft and crew were transferred to Euravia and Euravia two years later on obtaining Britannia aircraft changed the name to Britannia Airways.

CB: Ah, right

AJ: So, initially we operated 749s on inclusive tours mainly but later we started to operate Britannias, not only on inclusive tours, we had occasional rather interesting charter flights to various parts of the world. One such, interesting but not very pleasant, was evacuation of British, Belgian population from Leopoldville in

CB: In Congo

AJ: Belgian Congo. The unpleasantness of that was that we had to night stop in Leopoldville and to get to town we had to go through several military checkpoints at night and military checkpoints were of course Congolese military and they all drunk and automatic pistols it was not very pleasant to be stopped by troops, whatever they are, when they are drunk and armed with automatic pistols [laughs]. I remember that I had to stop three times in Leopoldville and every time it was rather, if I may say so, frightening experience [laughs] but anyway we managed to transfer some of the Belgian civilians from Leopoldville and by then we were, as I said, we were operating Britannias and shortly after that with this development of inclusive tours and Britannia decided to buy Boeings and I was posted together with other pilots to Seattle to train on Boeing 737-200 series, very interesting two months, a technical course first in Seattle, then simulator flying and then eventual flying on 737. And that was beginning of operation Boeing 737 which lasted for several years and then there was break because company decided to start operating to the West Coast of United States and to do so they managed to obtain two lovely aircraft, was a Boeing 707-320 Intercontinental, that was the most lovely aircraft I ever flew and we were operating the 707s to the West Coast, mainly to San Francisco, to Los Angeles, to Canada, Vancouver, occasionally to Tokyo via Anchorage, polar route to Anchorage, so always very interesting and also I was, for six months I was transferred to British Caledonian because they ran out of, they were short of crew and I was posted to join them for a few months and rather unpleasant sort of posting because I was operating South American routes, operating to Santiago, to Chile. Now, Chile at that time was run by president Allende, communist, he was elected Communist president but the whole country was trying to get rid of him because the country was in chaos there was, shops were closed, there was shortage of food, in the hotels food was rationing, we had to take some food off the aircraft to reinforce our ration in the hotel and as you know eventually military took over. I was the last aircraft to leave before the revolution, so I remember how the aircraft, how the country looked during President Allende regime, and I was the first one to land after, with military already in command and all of a sudden the country changed completely, all shops were open, plenty of food, wine shops open, the lovely Chilean wine in hotel, everything was in perfect, so I know that British public and particularly British press very much in favour of President Allende and they hated the idea of military takeover but to us who operated [unclear] the difference between what it was like during the Allende regime and later was very noticeable and to be quite honest we were on the side of Mrs Thatcher [laughs], side of Mrs Thatcher. After these few months with British Caledonian, I was getting close to my retiring age and eventually I retired at the age of sixty. My last flight with Britannia was on 22nd of December in 1982. And I was immediately offered the position of ops manager with Air Europe in Gatwick. I started to work there and at the same time a friend of mine, Mike Russell, who was training [unclear] Britannia Airways, he informed me that he bought Rapide aircraft, that was an aircraft that [unclear] operated [unclear] and he asked me if I would like to occasionally fly for him out of Duxford, the Imperial War Museum in Duxford with the passengers to show them how the old airliners used to look and fly before, in 1930s and soon after the war and I agreed and every weekend practically I used to go to Duxford to fly the Rapide for him. So, as you can see, I commenced my civil flying on Rapide aircraft and I completed my last flight, civilian flight was also on a Rapide and that’s, that’s the end of the story.

CB: Amazing, yes. Thank you, we’ll stop for a bit.

AJ: We

CB: We are just taking a step back now to when you arrived in the UK, what happened?

AJ: As soon as we arrived in UK, the courses were arranged by the local authorities to teach us or to commence to teach us English and it was normally arranged but sometimes by military, sometimes by local authorities. In RAF of course it was standard procedure that we had to attend lectures in English practically every day, that’s in RAF, in the army it was sometimes arranged by the local authorities, as far as I remember, but somehow, somehow we managed [laughs] in spite of difficulties, it’s not easy to learn the language when one is over twenty, but we managed somehow

CB: Who were the people who did the training, the courses in English for you? What sort of people, were they schoolmasters or what?

AJ: The, in RAF they were mainly lecturers from Oxford and Cambridge [laughs], mainly young lecturers from Oxford and Cambridge and so, I didn’t pick up the accent but [laughs], but anyway they were very good. They were excellent lecturers. And lectures were all in English

CB: But

AJ: And we managed, but somehow we managed

CB: They were part of the RAF education department

AJ: Yes, commission

CB: Yeah

AJ: Commission area and they were teaching us [laughs]

CB: And

AJ: Mainly very young lecturers

CB: They were, yes. And how did they deal with that because you had two requirements, one was the basic understanding of English, wasn’t it? Then the other one would be technical English for flying, so how did that

AJ: That used to go together with lectures, during lectures of course we, we learned the technical language, how these things are called in English and that was fairly easy and also we had sort of general lectures to improve our ability to express ourselves [laughs]

CB: So, how many of you were on this course?

AJ: Sorry?

CB: How many people were being trained with you at the same time?

AJ: [unclear], about twenty, normally about twenty [unclear]

CB: Right. Were they all Polish or were some Hungarian and Czechoslovakian?

AJ: Only Polish

CB: Right

AJ: No, we, in those days there were no Hungarians, [unclear] only Polish. As I said, our relationship with lecturers were very, very good [laughs]

CB: So, off duty, cause you were all the same age so, off duty what did you do?

AJ: [laughs] So we, we managed somehow

CB: But you would go to the pub, would you, with them, off duty, or what would you do?

AJ: Oh yes, yes, always, nearest one [laughs]. My social life was always pleasant, particularly when I was based in Blackpool for a while, I remember, the social life there was very pleasant because Squires Gates was quite close to St Annes and there were very pleasant girls living in St Annes [laughs], it was, rather pleasant

CB: And were there lots of dances?

AJ: Oh yes, yes, we, dancing was a typical past time during the war [laughs]

CB: And cinema?

AJ: And cinema as well

CB: Did the

AJ: We, in, when we were based in Benbecula, we had a special sort of supply of new Hollywood productions, always first of all they used to arrive us to show us the film that appeared in London about a week later [laughs]

CB: [laughs]

AJ: That was just to try, trying to make our unpleasant life in Benbecula just a little bit more pleasant

CB: Yes

AJ: I assume Benbecula is a dreadful place for weather, sometimes the winds were size eighty miles an hour [laughs] and it was difficult to sleep because of the noise

CB: Oh, really?

AJ: And quite often unfortunately the airfield was closed by the weather

CB: Yeah

AJ: [unclear] divert

CB: This is on an island on the west coast of Scotland. What was the accommodation like?

AJ: Mainly Nissen huts

CB: Right

AJ: I think the only brick house on the station was a squash court [laughs], the rest was all Nissen huts [laughs]. But squash court was brick [laughs]

CB: Now you were used to a different type of food and catering in your youth so how did you adapt to the British diet?

AJ: Oh, there was no problem. Polish diet here, if Polish families was a little bit close to British because food was rather scarce and was difficult to arrange Polish menu [laughs]

CB: Yeah

AJ: Which was rather rich and

CB: Yeah. Now, this business of learning English, so you are learning English for a social conversation but when you came to learn RT, radio telephony, then was it more difficult to deal with English that way?

AJ: No. I think, no, we had no difficulties on the radio, we used standard procedure and standard language

CB: Yes

AJ: Limiting the conversation to absolute minimum, only necessary information absolutely necessary, we were not allowed to run long conversation, before operation of course there was a general arty silence, complete silence before operational flight, we were not allowed to use radio for to get permission for take-off, was all visual

CB: All done with [unclear]

AJ: All visual

CB: Yeah

AJ: Yeah, so not to, you’re doing everything possible to, not to tell the Germans where we were or what we were doing

CB: Yes. Thinking of how the process of training, so you did your initial training on what aeroplane?

AJ: On Tiger Moths

CB: Right. And after the Tiger Moth, what did you?

AJ: Oxford

CB. Onto the Oxford

AJ: Oxford

CB: For your twin engine flying.

AJ: Yes

CB: Then what?

AJ: Oxford and then I, when I was posted to First Air Armament School, it was Blenheim I and IV

CB: Right

AJ: Again we converted, on arrival there we had to pass conversion course, which was run by local training, training officer

CB: Now you said we, does that mean you were all Poles or was there a mixture of people on all these courses? Were you all Polish people on the training, or was there a mixture of nationalities?

AJ: No, mainly all Polish and sometimes some Czechs. But Czechs from different squadrons, we had our Polish squadrons, [unclear] few Czechs served with Polish Air Force. Among them was the highest scoring pilot in the Battle of Britain. He was, his, he was Polish by nationality but he was born Czech

CB: Ah

AJ: So his nationality was actually Czechoslovakian,

CB: Yeah

AJ: But he was Polish

CB: Polish born

AJ: Citizen

CB: Ah, right

AJ: It was flight sergeant Frantisek, he was the highest scoring pilot in the Battle of Britain but we never say he was Polish, he was Czech [laughs]. Unfortunately, he was killed during the battle

CB: So after you were on Blenheims, what did you move to next?

AJ: To Wellingtons

CB: Right

AJ: So, in the RAF, I flew Tiger Moths, Oxfords, Ansons, Blenheim I and IV, Wellington X and XIV, Warwicks and DC-3s. The DC-3 was mainly in Transport Command conversion unit

CB: Right

AJ: That was all. We were due to fly DC-3s in India but

CB: Ah, so you went to conversion unit

AJ: Didn’t happen [laughs]

CB: Now, you were all being trained together, in Bomber Command at the OTU, the various specialities were pilot, navigator and so on, were put in a room and they then made a self-selection of a crew, how was your crew put together as Polish people?

AJ: Mainly by sort of knowing each other and for first few months were lectures so it was easy to know the, to become aware of that particular, he must be a good navigator [laughs], so I used to ask him, would you join my crew [laughs]? As exactly my navigator was a lawyer from Krakow University [laughs] and I thought, oh, he’s a lawyer, he must be good navigator [laughs] and he was, he was, unfortunately he was not very healthy

CB: And the crew of the Wellington with six in Bomber Command, in Coastal Command what was the crew numbers? How many people in the crew in Coastal Command?

AJ: In the crew? Six

CB: Right. So, who ran the ASVE? Who ran the ASV Set?

AJ: Sorry, I didn’t

CB: Yeah, you had the airborne radar, the ASVE

AJ: Yes

CB: Who’s job was it to run that?

AJ: Who, radar?

CB: Yeah

AJ: Well, all three radio navigators were trained gunners, radio officers, and radar operators and during the operational flight, they changed every two hours

CB: Right

AJ: They changed rotation, one, two hours in the rear turret, two hours at the radar and two hours at radio station,

CB: And you said that when you went on ops, then they were long and you had extra tanks, what was the nature of the sortie? Would you drive, fly to a long, the farthest point and then do a square search or what did you do?

AJ: We managed to go to the patrol area and then we patrol, mainly box patrol in a certain area, sort of and there was one aircraft operating this sector, the next aircraft, several aircraft was sort of blocking say Western approaches

CB: Right. And what height would you be flying?

AJ: Fifteen hundred feet

CB: Right

AJ: We were flying at fifteen hundred feet mainly

CB: So, how often did you use your armament when you were on ops?

AJ: Well, [unclear] we didn’t have, we didn’t attack submarine [unclear] but what you’re trying to do is to try to keep submarines submerged and several times we picked up a good contact but as soon as we started flying towards it the contact disappeared because they could see us on their radar or could hear us

CB: Cause they had a radar detector didn’t they?

AJ: And they of course submerged very quickly and changed course. So it was very difficult to. In 1943 the Germans decided to not to dive but to accept and fight and they armed the submarines, it was a very heavy armament and it was extremely dangerous to attack submarine because of heavy anti-aircraft armament on the submarine and the attack was normally from between fifty and one hundred feet, we had electrical altimeter

CB: Ah, right

AJ: To get down to a very low altitude [unclear] and we had to illuminate the target with Leigh light, the aircraft was equipped with a very heavy reflector which used to be lowered hydraulically and the navigator, just about a mile from the target used to illuminate and he could control the reflector to pick up the target first standing above him were the [unclear] machine guns and of course as soon as he saw the target he used to open up to the front guns, a very high rate of fire, Browning machine guns, they were like automatic pistols, mainly anti-personnel guns

CB: Yeah

AJ: And very high rate of fire, very close to one thousand five hundred rounds a minute so and that was type, the radar operator was to sort of directing the aircraft towards the target until it was about a mile from the target, about a mile from the target the navigator used to illuminate the target

CB: Where was the Leigh light mounted in the aircraft?

AJ: Sorry?

CB: Whereabouts in the aircraft was the Leigh light?

AJ: It was in the middle of the fuselage

CB: Pardon?

AJ: Middle of the fuselage, underneath

CB: Ah, middle of, right

AJ: Used to be

CB: Ahead of the bomb bay, was it?

AJ: And that’s why ditching on Wellington XIV was never successful because the fuselage used to break just where the Leigh light was so there was never, not one Wellington XIV ditched successfully

CB: Really? Yes

AJ: Cause was the weak point

CB: Yeah

AJ: In the fuselage, so

CB: Now

AJ: General, general sort of method of attack which we trained of course all the time was to, as soon as the target was picked up by radar, to obey the instructions from radar operator to direct the aircraft towards the target [unclear] come down to about a hundred feet, sometimes even lower, and about a mile from the target illuminate the target [unclear] and attack six depth charges, it was a stick of six depth charges so if that was the target [unclear] six [unclear]

CB: Was the method of attack

AJ: That was the method of attack

CB: To the side of the submarine or head on?

AJ: No, we used to drop the depth charges trying to in front of it so that the submarine ran into them but it, as I said, it was not easy, you can imagine at night submarine firing back at you [laughs] and to aim six depth charges to drop in front of the submarine in the direction the submarine was heading, it’s, it required quite a lot of courage to

CB: I can imagine. What about the other members of the squadron? How many of those attacked submarines?

AJ: I can’t tell you exactly but aircraft, we had some success but not during the time when I was in the squadron because then German submarines were equipped with [unclear] and they could stay submerged for a very long time, in fact the only time, the only possibility of finding the submarine was to observe the sea and to see the smoke coming, providing wind was not too strong, it was possible to see the smoke just like smoke of the train going through the depression

CB: From the diesel engine

AJ: You could see the, you could see the puffs of smoke coming out from sea [unclear] that was the submarine and

CB: Because

AJ: It was to attack, but of course submarine dived before that [laughs] because they were on the periscope all the time and they could see the aircraft approaching so they would crash land, crash dive

CB: Yeah. So the period that you were with the squadron on these anti-submarine duties was quite short. Did you feel disappointed that you hadn’t had enough time?

AJ: Yes

CB: How did you feel?

AJ: Sorry?

CB: How did you feel?

AJ: I felt that the war avoided me [laughs]

CB: Yeah

AJ: That was my feeling. I wanted, you know, I thought that I’d do at least one tour in Coastal Command and then I would, that I would go back to Bomber Command, but it never happened,

CB: No

AJ: War ended

CB: So, as a Pole in England, in Britain, did you feel a particular sense of urgency to do something about Germans?

AJ: About?

CB: The Germans and submarines. Did you feel you really wanted to make a mark?

AJ: Sorry, I didn’t quite

CB: Well, as a Pole, in view of what the Germans did to Poland, did you feel, putting it a different way, that you really wanted to pay them back?

AJ: Well, that was a general thing that you wanted to, as you know the, towards the end of the war we realised that we in Poland is the only country had lost the war

CB: Because of Yalta

AJ: We knew that sooner or later Germans will be supported by United States not only because of the power of Russia but because of industrial power that it represented and what can we say, it was few rather unpleasant years, we were absolutely certain that there will be friction between the West and East but we also knew that it will not be a major war because of the danger of atomic power but you knew that there will be some small wars like Korea and others. Nowadays we are on reasonably good terms with the Germans but memories last for a long time

CB: Yes. And after the war, what was the general feeling of Polish people, that war had finished and how did the Polish people feel about it?

AJ: Well, we were all, as you know, we were all very disappointed, everyone was trying to organise himselves to get back to normal life, in spite of the fact that it will be away from Poland. We were all sort of rather disappointed but somehow we sticked together, we managed to stick together in our organisation and we knew that sooner or later something will happen but unfortunately it lasted for over fifty years

CB: Yes. But in the time after the war, in the fifties, there was the Hungarian and the Czechoslovak uprising, so how did the Polish people react to those?

AJ: You know, there was a very strong reaction in Poland although the Polish government was, then Polish government, Communist government was very much with the Russian policy, the general opinion of Poland, of Polish population was very much pro Czechoslovakia, later on pro Hungary and eventually problems, troubles started in Poland, we started [laughs], Solidarity, this, we knew that sooner or later something will happen, but we were not certain how long it would take

CB: Just finally going back to when you came to Britain

AJ: Mh?

CB: When you first came to Britain, what was the reaction of the population?

AJ: Initially, it was very friendly, very friendly indeed, particularly that was time of Battle of Britain and was well known fact that Polish fighters were fighting together with RAF, Polish Navy was still in action, together with Royal navy, Polish forces defended, together with Australians defended Tobruk, they distinguished themselves in Norway before that, in Narvik [laughs], so there as, Poland was popular initially, but towards the end of the war, change, everything changed completely

CB: Did it?

AJ: Russia was the great ally and we, we were the troublemakers, we tried to create trouble between the West and Russia, that was the general opinion

CB: Was it? Really?

AJ: But of course change, things have changed very slowly, changed again because Russia begin to show their power and there was of course Berlin airlift and all those difficulties created by Russia and we all knew about it, this is part of the Russian policy to establish Communist regime everywhere

CB: Right, we’ll stop there a mo. Now, after the war, then a lot of squadrons and the Air Forces created associations, so, the RAF had squadron associations and there was a Polish Air Force association

AJ: Yes, Polish association was established very soon after the war, initially as soon as war over it started to become but the year it was established actually in 1945, 1945 and initially it was created by Polish Air Force senior officers, junior officers and other ranks were sort of more interested in getting themselves organised initially but later on everyone sort of joined in and the Polish Air Force Association was one of the biggest organisations, Polish organisations in UK. We all, the Polish Air Force Association was helped by the Royal Air Force association and we established a very good contact with the RAF, Royal Air Force Association, several clubs were formed very quickly, clubs one in London and one in Blackpool, one in Nottingham, Derby and so on, and generally speaking it was

CB: Just a couple of minutes

AJ: Generally speaking, it was very sort of organisation, which was very active, very active socially

CB: Yes

AJ: And of course, initially was also helping the former members of Polish Air Force to establish themselves here or in other countries, United States, Canada, Argentina even [laughs]

CB: Yeah

AJ: So

CB: And then the memorial, so a memorial was established, built at Northolt

AJ: Yes, the Polish Air Force memorial was built rather early, soon after the war. It was unveiled by Lord Tedder and later on it was enlarged and now it just exists [unclear] we have ceremony there every year

CB: Yeah

AJ: Was a tradition to have one, wreath laying ceremony in September every year. And another memorial was built in Warsaw, giving the, with names of all the aircrew that had lost their lives during the war. If you are in Warsaw, you go and see that memorial, it is one of the nicest memorials in Warsaw.

CB: Now, after the war you were busy flying airliners so, to what extent did you get involved with the Polish Air Force association?

AJ: Well, initially when I was flying, it was rather difficult because I was busy all the time but towards the end, when I started working in Gatwick as ops manager, I started to work for the Polish Air Force association, initially as chairman of London branch, and then as honorary secretary, vice chairman [laughs], gradually I went up in a position in Polish Air Force Association, in a

CB: And you became the chairman

AJ: Sorry?

CB: And you became the chairman

AJ: Well, chairman of Polish Air Force Association charitable trust

CB: Right

AJ: That was at the end of existence of Polish Air Force Association. Polish Air Force Association organised trust from all the remaining [unclear] the organiser trust

CB: Yeah

AJ: Which was very active for several years and

CB: And that then lead to the Polish Airmen’s Association

AJ: [unclear] what [unclear] is now Polish Airmen’s Association

CB: Yeah

AJ: Mainly sort of consisting of families, families [laughs]

CB: Yeah

AJ; But there are still a few of us

CB: You’re active in that still, aren’t you?

AJ: Few of us remaining [laughs]

CB: Thank you

AJ: Thank you

AJ: Well, I was, as I said, I was born in Warsaw and first few years I, we lived near Gdansk, in Sopot because my father was an officer in the Polish Navy. My father served during the First World War in the Navy but shortly after I was born, he transferred to the Air Force and he reached rank of Colonel eventually. We, initially we stayed in Sopot in Gdansk then we moved to Warsaw and shortly after that my father was sent to Paris for two years to Ecole Superior [unclear] for further technical studies, he was actually diploma engineer and he was sent there for further studies on airline engines and airframes. On return to Poland, we, my father was initially posted to Deblin, which is the Polish Air Force Academy and we stayed there for four years, that was my sort of first contact with the Air Force. We returned to Warsaw in, round about 1930-31 and I commenced schooling in Warsaw, in Poniatowski Gymnasium [laughs] but that’s not very important. And I, and we stayed in, lived in Warsaw until the outbreak of war, in fact I remember in 1939 I returned from the summer holiday on the 28th of August 1939 and I was getting ready to go back to school when in the morning of the 1st of September I was awakened by the gunfire and sirens. I ran into the garden and I saw the formation of German bombers surrounded by the puffs of explosion from the anti-aircraft guns and that was it, that was the beginning of the war. And my father was recalled back to [unclear], he was already retired and worked as engineer in the [unclear] aviation factory in Warsaw but he was recalled back to service and he was posted to South-Eastern Poland with a group of officers to receive the aircraft that was sent from Britain via Constanta, unfortunately the aircraft only reached Constanta harbour and they were never offloaded because of the advance of, very quick advance of the German forces. Aircraft were Fairey Battle, even that all, that useful to Poland because it was a light bomber, really, and we needed fighters but neither France or Britain could provide fighters, they were rather short themselves. Anyhow, we, my mother on the 5th of September, my mother decided that we follow our father to Lviv, to South-eastern Poland and we left Warsaw for Lviv and we stayed in Lviv for several days and on the 17th of September when Russia attacked Poland we travelled across the border to Romania where we re-joined my father in Romania, he was already across the border. We stayed in Romania for about a month I think and then we travelled via Yugoslavia, Italy [unclear] to Paris, to France. Initially I was a little bit too young to join the forces, so I went back to lycée, back to school. It was a Polish Lycée that existed in Paris for many years before the war. Anyway, I started my school again in Paris. In, one [unclear], I completed the first year of study, was actually lycée for last two years before matriculation. When offensive started, German offensive started, my father agreed that I would join the Army and I was, I passed my, all the tests in Paris and the interviews and I was posted to cadet officer’s school near Orange, I think the name was Bollene but I am not sure, don’t quote me that, I only managed to reach Bollene when France collapsed and school was evacuated via Saint-Jean-de-Luz and to Plymouth and from Plymouth up to Scotland to Crawford in Scotland. In Scotland we continued our training very quickly, it was amazing how quickly everything was organised, initially we were issued with infantry armament but shortly after that [unclear] carriers arrived and Valentine tanks and we trained, completed our training by November 1940, we completed our training and I was made the cadet officer, corporal cadet officer [laughs]. The, shortly after I completed my training, the Polish forces decided that, to be an officer, I must get my matriculation, in other words pass my what is the A level exam the Matura [laughs]. So, I was posted back to the same school that I was in France, that school was evacuated as well to England, to Scotland and it was in Dunalastair House near Pitlochry in Perthshire, very beautiful place [laughs]. Anyway, I was sort of released from the, for six months, from the forces to complete my study and pass my matriculation, well, I only had six months, it was difficult, but I managed and I managed to pass all the exams and I went back to the tank corps, it was 16 Tank Brigade number 2 Battalion of tank corp. Round about that time, I decided that I must try to transfer to the Air Force and I started to applying to be transferred to the Air Force, explaining that I have sort of family links with the Air Force [laughs] and I asked them to consider this and transfer me to the Air Force. Eventually, I managed [laughs] and in beginning of 1942 I commenced my training as a pilot. Training initially was four months of ground training in preparation for flying, then, after short leave, initial flying in Hucknall near Nottingham and from there another four months service flying school at Newton, also near Nottingham. I completed my training, I obtained my wings, and also I obtained my commission [laughs], which was organised [laughs] and I was posted to RAF Manby, which was the first Air Armament School, it’s half, about half way between Peterborough and Grimsby, a line between Peterborough and

CB: It’s in Lincolnshire, yes

AJ: RAF Manby

CB: Manby

AJ: First Air Armament School, pre-war station, the station commander was Group Captain Ivens, First World War pilot, rather severe but we [unclear] [laughs] and [unclear], he had certain sympathy towards us and he was a good station [unclear] and we spend many months flying there and I was flying as a staff pilot, flying Blenheims IV and Blenheim I on mainly bombing training. Well, after many months of that, I was suddenly posted to Squires Gate to a general reconnaissance course which meant that I will be posted to Coastal Command because it was mainly navigation training for flying over the sea. It was just over two months course, rather severe but that course helped me a lot in the future because I obtained second class navigation warrant and that helped me in obtaining my licence later on, civvy licence. Eventually, after completion of training in Squires Gate, I was posted to the squadron, which was based in Chivenor and I started flying as a second pilot. Initially, one had to do at least ten, sometimes more flights as a second pilot before being posted to Operational Training Unit to pick up his own crew. Well, I did my ten operations mainly flying over the Atlantic. The flying was consist of patrols, long ones lasted, patrols lasted for over ten hours, we had special additional fuel tanks in bomb bays, apart from depth charges, aircrafts was Wellington XIV, especially designed for operations in Coastal Command, it was equipped with ASV, Aircraft-to-Surface Vessel which was, although it was a primitive radar, it was a very good radar, we could pick up contacts distance over one hundred and twenty miles, that if contact was large enough [laughs], it was, flying was tiring but I found rather interesting it, weather was not in favour of us particularly when we were based up north in Benbecula the weather was our greatest enemy, flying sometimes in very terrible conditions over the Atlantic and several times we had to be diverted to different fields because weather was closing on, closing the fields on the west coast of Scotland so we had to be posted sometimes to Northern Ireland to Limavady. It was interesting and eventually I was posted to Operational Training Unit to Silloth, RAF Silloth that was 6 OTU Coastal Command to pick up my own crew. We completed our training there, we were posted back to squadron and just as we completed initial sort of training with the squadron, war ended and that was the end of my war, but the squadron was posted to Transport Command and I was posted to Crosby-on-Eden Transport Command Conversion Unit, it was a tough three months course for pilots, getting them ready for operation in Transport Command, it was tough course but again that course helped me in obtaining my civvy licences later on. In, on return from, unfortunately I was due to go to India with my crew, getting ready to be posted to India but unfortunately my navigator failed the last of overseas medical, they discovered that he suffering from anginal heart and I lost my navigator and because of that I was posted back to the squadron, 304 Squadron, which in the meantime, was operating as Transport Squadron from Chedburgh, and that was the squadron operated Warwicks, sort of large Wellington [laughs] transport plane, and operating mainly to Athens with [unclear], we operated via east, Pomigliano near Naples and then Athens and back again [laughs]. And I stayed with the squadron until the end of the existence of Polish Air Force and we were all transferred to Polish resettlement call but I decided to continue flying and I was posted to [unclear] Navigation School and I flew Wellingtons, Wellington X, from Royal Air Force Topcliffe in Yorkshire and I was there for about a year and a half until I was asked to relinquish my commission and I went back to civil life, civilian life, but, as I said, I managed to complete two very important courses in RAF and that helped me quite a bit in passing the exams for airline transport pilot licence. And I, in possibly 1948 when I commenced my flying in civil aviation. Initially, my first employment was in, up in Blackpool and I operated Rapid aircrafts, De Havilland Rapide over the Irish Sea from Blackpool to Ronaldsway and to Dublin and Belfast and Glasgow, for about, for a whole year I was operating over the Irish Sea for Lancashire Aircraft Corporation, that was the firm I was employed with, Lancashire Aircraft Corporation. Lancashire Aircraft Corporation later changed name to Skyways and I stayed with the firm and I was, after a year in Blackpool, I was moved to Bovingdon to join the crew of captain Raymond, very good pilot, to operate Haltons, a transport plane, Halton was a civil version of Halifax 8 C and we used to operate freighting services to, well, yes, we used to fly everywhere, to the Far East, to Singapore, to Island of Mauritius [laughs] on the Indian Ocean, to the, all around the Middle East and but in about, after about a year operating with, flying with Captain Raymond we had a rather, in fact very unpleasant incident. We were due to take eight tons of optical instruments, four tons from UK and then four tons from Hamburg and operate to Hong Kong. We took off early in the morning, must have been seven o’clock in the morning, beautiful day, we climbed to our cruising altitude which, as far as I remember, was nine thousand feet, and I just went down to my navigation cabin to start my navigation, I obtained first pinpoint I remember at [unclear], I’ve written it on my logbook, when fire bell rang. I rushed back to the cockpit and I saw the number one engine on fire, it was not only fire but black smoke, we turned back towards Bovingdon but just at that time, just looking at that engine when the whole engine separated, the engine cracked in second row of cylinders, just cracked, and propeller, reduction gear, cowlings and front part of the engine just separated and took fire [unclear], and propeller just sort of twisted right and hit the leading edge of the aircraft, between the engines and cut through the leading edge and through the oil tank of number one, number two engine and a few moments later engineer had to stop number two engine because of lack, he was losing oil. Anyway, we were still at about eight thousand feet and we flew towards Bovingdon, Bovingdon also of course helping us with QDMs etcetera, help passing all the weather information etcetera and weather, as I said, was absolutely perfect, I could see Bovingdon from great distance I could see the runway and captain Raymond decided that we would land crosswind on as long runway accept crosswind was about ten knots and land direct on a long runway and we made a superb approach, or actually captain Raymond did [laughs] and we landed safely in Bovingdon. The aircraft looked terrible. One engine gone, one engine feathered, the aircraft covered with oil and dirty smoke [laughs], remnants looked absolutely terrible but would you believe, the engineer managed to fix it in three days, they replaced the engine, replaced the tank, replaced the leading edge and three days later aircraft operated to Milan. It was almost unbelievable [laughs]. But anyway, great work on British engineers [laughs]. So that was a rather unpleasant beginning of my long service with civil aviation, would you like me to continue?

CB. We’ll stop just for a minute.

AJ: Sorry?

CB: We’ll stop just for a moment. So, we are talking about Skyways and the incident with captain Raymond,

AJ: Yes

CB: But after that you got, what happened to you, you got your own command?

AJ: After that I started flying as a captain, we converted from Haltons to Avro York. I don’t know if you know the aircraft

CB: I know

AJ: [unclear]

CB: The Lancaster

AJ: And we started to operate mainly to the Middle East

CB: Right

AJ: Mainly to a place called Fayid in Canal Zone, that was of course in military zone of Canal Zone and civilian planes were not allowed to land there because of agreement between Egypt and UK, that only military planes would be landing on Canal Zone so we were all given a complementary commission between Malta and Fayid we operated as RAF crews on RAF markings and everything, we were back in uniform for a little while. The operation to the, there was always something happening when we were there, I remember first sort of international problem was the Iran, the, Mr Mosaddegh trying to get Abadan

CB: The oil field

AJ: [unclear] Abadan

CB: Yes

AJ: So we were all put up in uniforms and transferred to Castle Benito in Libya, later Castle Idris, artillery was loaded on our aircraft and we were all ready to occupy Abadan [laughs] but fortunately nothing happened, Shah returned to Iran and don’t know what’s happened to Mr Mosaddegh, but anyway he disappeared. So that was the first sort of international incident that I have seen and the next one of course was Suez, that was during the premiership of Mr Eden when Nasser, President Nasser decided to nationalise Suez Canal and of course there was a war between Israel and Egypt and Israel occupied Sinai peninsula and we were also involved, immediately involved in transferring flying troops not only to Cyprus to reinforce the Polish British base, there but also to other parts where there was a danger to the British [unclear] in Bahrein, Aden we had to fly troops there, also we had to evacuate British personnel from Castle Benito because of the danger in revolt in Tripoli. There was of course a big row between United States on one part and France and UK on the other but anyway everything slowly settled down and we started to operate via Cyprus to the Far East, mainly on trooping contract again. Cyprus was very pleasant place initially after the war as far as I remember, but slowly EOKA started to operate and things started to get really nasty, well, in fact, we lost one aircraft, EOKA managed to plot to put bomb on, in the gallery of one of our aircraft departing from Nicosia to UK with RAF families. The captain on that flight was I remember captain Cole and they were travelling from the hotel in Kyrenia via through the Kyrenia Mountains they had a puncture and the wheel was damaged, anyway they were delayed about forty five, fifty minutes to arrive at the airport, they were of course in a hurry, immediately [unclear] ran to the aircraft to distribute pillows and get cabin ready for the families to join the aircraft and the engineer was on a wing and captain, captain Cole and his first officer were walking towards the aircraft from the control tower, they were about half way, when bomb exploded in the gallery. The aircraft was immediately on fire, but it was a Sunday, was it Sunday? No, it was, only day but lunchtime and everything was quiet on the airfield, just one aircraft getting ready to departure was our aircraft, well, I mean, firm aircraft not mine [laughs], and the fire tender and all the emergency equipment parked near control tower, they didn’t expect anything, it was a very hot day and the crew of fire tenders had sort of undone their buttons and they were sort of sunning themselves and they didn’t notice that bomb exploded, was just [mimics a detonation] was a very small, small bomb and of course the captain, first officer noticed that, there were explosions and they started to run towards control tower to tell, to call the fire and the controller didn’t know, he was looking at them and sort of, he went on the balcony, he said, what? Aircraft on fire. So he ran back, pressed the button alarm but by the time fire tender alarm, the aircraft was gone

CB: Completely

AJ: Lost an aircraft. No one was hurt, the engine, when bomb exploded this engineer was on a wing, he almost fell off the wing but he didn’t [laughs] fortunately, girls were distributing pills in the cabin so they ran out of the cabin, no one was hurt but aircraft was lost. If you visit Nicosia, visit the museum, there was, there is a place, commemorating EOKA activities and there is a photograph of that aircraft, EOKA sort of proud that they managed to destroy one aircraft but they nearly, the aircraft was, the bomb was so timed to explode at the top of climb, had it not been for the puncture of the car bringing the crew from Kyrenia, the aircraft would have been at top of climb and that would have been it, six, over sixty RAF families, women and children were due to fly back to UK, that was one of the things that

CB: Fascinating, yeah

AJ: I still remember. The, after that, we, after that incident we started to operate trooping contracts to Far East, mainly to Singapore. We changed aircraft from Hermes to Lockheed 749s Constellation and of course it was much beautiful aircraft, lovely aircraft to fly and we initially started operating with troops to the Far East, to Singapore but later this changed into the freighting contract for BOAC to the Far East, that’s operating freight from UK to Hong Kong and to Singapore and I was posted for two years to New Delhi to operate the sector between New Delhi and Hong Kong and Singapore. It was interesting posting, India is an interesting place and it was lovely flying, one week of flying, one flight to Singapore, one flight to Hong Kong in a week and then a week off [laughs], rather pleasant and it was, generally speaking, I remember that as a very pleasant, very pleasant stay in India. As [unclear], when I returned from India, the Skyways decided to finish the operation and all the aircraft and crew were transferred to Euravia and Euravia two years later on obtaining Britannia aircraft changed the name to Britannia Airways.

CB: Ah, right

AJ: So, initially we operated 749s on inclusive tours mainly but later we started to operate Britannias, not only on inclusive tours, we had occasional rather interesting charter flights to various parts of the world. One such, interesting but not very pleasant, was evacuation of British, Belgian population from Leopoldville in

CB: In Congo

AJ: Belgian Congo. The unpleasantness of that was that we had to night stop in Leopoldville and to get to town we had to go through several military checkpoints at night and military checkpoints were of course Congolese military and they all drunk and automatic pistols it was not very pleasant to be stopped by troops, whatever they are, when they are drunk and armed with automatic pistols [laughs]. I remember that I had to stop three times in Leopoldville and every time it was rather, if I may say so, frightening experience [laughs] but anyway we managed to transfer some of the Belgian civilians from Leopoldville and by then we were, as I said, we were operating Britannias and shortly after that with this development of inclusive tours and Britannia decided to buy Boeings and I was posted together with other pilots to Seattle to train on Boeing 737-200 series, very interesting two months, a technical course first in Seattle, then simulator flying and then eventual flying on 737. And that was beginning of operation Boeing 737 which lasted for several years and then there was break because company decided to start operating to the West Coast of United States and to do so they managed to obtain two lovely aircraft, was a Boeing 707-320 Intercontinental, that was the most lovely aircraft I ever flew and we were operating the 707s to the West Coast, mainly to San Francisco, to Los Angeles, to Canada, Vancouver, occasionally to Tokyo via Anchorage, polar route to Anchorage, so always very interesting and also I was, for six months I was transferred to British Caledonian because they ran out of, they were short of crew and I was posted to join them for a few months and rather unpleasant sort of posting because I was operating South American routes, operating to Santiago, to Chile. Now, Chile at that time was run by president Allende, communist, he was elected Communist president but the whole country was trying to get rid of him because the country was in chaos there was, shops were closed, there was shortage of food, in the hotels food was rationing, we had to take some food off the aircraft to reinforce our ration in the hotel and as you know eventually military took over. I was the last aircraft to leave before the revolution, so I remember how the aircraft, how the country looked during President Allende regime, and I was the first one to land after, with military already in command and all of a sudden the country changed completely, all shops were open, plenty of food, wine shops open, the lovely Chilean wine in hotel, everything was in perfect, so I know that British public and particularly British press very much in favour of President Allende and they hated the idea of military takeover but to us who operated [unclear] the difference between what it was like during the Allende regime and later was very noticeable and to be quite honest we were on the side of Mrs Thatcher [laughs], side of Mrs Thatcher. After these few months with British Caledonian, I was getting close to my retiring age and eventually I retired at the age of sixty. My last flight with Britannia was on 22nd of December in 1982. And I was immediately offered the position of ops manager with Air Europe in Gatwick. I started to work there and at the same time a friend of mine, Mike Russell, who was training [unclear] Britannia Airways, he informed me that he bought Rapide aircraft, that was an aircraft that [unclear] operated [unclear] and he asked me if I would like to occasionally fly for him out of Duxford, the Imperial War Museum in Duxford with the passengers to show them how the old airliners used to look and fly before, in 1930s and soon after the war and I agreed and every weekend practically I used to go to Duxford to fly the Rapide for him. So, as you can see, I commenced my civil flying on Rapide aircraft and I completed my last flight, civilian flight was also on a Rapide and that’s, that’s the end of the story.

CB: Amazing, yes. Thank you, we’ll stop for a bit.

AJ: We

CB: We are just taking a step back now to when you arrived in the UK, what happened?

AJ: As soon as we arrived in UK, the courses were arranged by the local authorities to teach us or to commence to teach us English and it was normally arranged but sometimes by military, sometimes by local authorities. In RAF of course it was standard procedure that we had to attend lectures in English practically every day, that’s in RAF, in the army it was sometimes arranged by the local authorities, as far as I remember, but somehow, somehow we managed [laughs] in spite of difficulties, it’s not easy to learn the language when one is over twenty, but we managed somehow

CB: Who were the people who did the training, the courses in English for you? What sort of people, were they schoolmasters or what?

AJ: The, in RAF they were mainly lecturers from Oxford and Cambridge [laughs], mainly young lecturers from Oxford and Cambridge and so, I didn’t pick up the accent but [laughs], but anyway they were very good. They were excellent lecturers. And lectures were all in English

CB: But

AJ: And we managed, but somehow we managed

CB: They were part of the RAF education department

AJ: Yes, commission

CB: Yeah

AJ: Commission area and they were teaching us [laughs]

CB: And

AJ: Mainly very young lecturers

CB: They were, yes. And how did they deal with that because you had two requirements, one was the basic understanding of English, wasn’t it? Then the other one would be technical English for flying, so how did that

AJ: That used to go together with lectures, during lectures of course we, we learned the technical language, how these things are called in English and that was fairly easy and also we had sort of general lectures to improve our ability to express ourselves [laughs]

CB: So, how many of you were on this course?

AJ: Sorry?

CB: How many people were being trained with you at the same time?

AJ: [unclear], about twenty, normally about twenty [unclear]

CB: Right. Were they all Polish or were some Hungarian and Czechoslovakian?

AJ: Only Polish

CB: Right

AJ: No, we, in those days there were no Hungarians, [unclear] only Polish. As I said, our relationship with lecturers were very, very good [laughs]

CB: So, off duty, cause you were all the same age so, off duty what did you do?

AJ: [laughs] So we, we managed somehow

CB: But you would go to the pub, would you, with them, off duty, or what would you do?

AJ: Oh yes, yes, always, nearest one [laughs]. My social life was always pleasant, particularly when I was based in Blackpool for a while, I remember, the social life there was very pleasant because Squires Gates was quite close to St Annes and there were very pleasant girls living in St Annes [laughs], it was, rather pleasant

CB: And were there lots of dances?

AJ: Oh yes, yes, we, dancing was a typical past time during the war [laughs]

CB: And cinema?

AJ: And cinema as well

CB: Did the

AJ: We, in, when we were based in Benbecula, we had a special sort of supply of new Hollywood productions, always first of all they used to arrive us to show us the film that appeared in London about a week later [laughs]

CB: [laughs]

AJ: That was just to try, trying to make our unpleasant life in Benbecula just a little bit more pleasant

CB: Yes

AJ: I assume Benbecula is a dreadful place for weather, sometimes the winds were size eighty miles an hour [laughs] and it was difficult to sleep because of the noise

CB: Oh, really?

AJ: And quite often unfortunately the airfield was closed by the weather

CB: Yeah

AJ: [unclear] divert

CB: This is on an island on the west coast of Scotland. What was the accommodation like?

AJ: Mainly Nissen huts

CB: Right

AJ: I think the only brick house on the station was a squash court [laughs], the rest was all Nissen huts [laughs]. But squash court was brick [laughs]

CB: Now you were used to a different type of food and catering in your youth so how did you adapt to the British diet?

AJ: Oh, there was no problem. Polish diet here, if Polish families was a little bit close to British because food was rather scarce and was difficult to arrange Polish menu [laughs]

CB: Yeah

AJ: Which was rather rich and

CB: Yeah. Now, this business of learning English, so you are learning English for a social conversation but when you came to learn RT, radio telephony, then was it more difficult to deal with English that way?

AJ: No. I think, no, we had no difficulties on the radio, we used standard procedure and standard language

CB: Yes

AJ: Limiting the conversation to absolute minimum, only necessary information absolutely necessary, we were not allowed to run long conversation, before operation of course there was a general arty silence, complete silence before operational flight, we were not allowed to use radio for to get permission for take-off, was all visual

CB: All done with [unclear]

AJ: All visual

CB: Yeah

AJ: Yeah, so not to, you’re doing everything possible to, not to tell the Germans where we were or what we were doing

CB: Yes. Thinking of how the process of training, so you did your initial training on what aeroplane?

AJ: On Tiger Moths

CB: Right. And after the Tiger Moth, what did you?

AJ: Oxford

CB. Onto the Oxford

AJ: Oxford

CB: For your twin engine flying.

AJ: Yes

CB: Then what?

AJ: Oxford and then I, when I was posted to First Air Armament School, it was Blenheim I and IV

CB: Right

AJ: Again we converted, on arrival there we had to pass conversion course, which was run by local training, training officer

CB: Now you said we, does that mean you were all Poles or was there a mixture of people on all these courses? Were you all Polish people on the training, or was there a mixture of nationalities?

AJ: No, mainly all Polish and sometimes some Czechs. But Czechs from different squadrons, we had our Polish squadrons, [unclear] few Czechs served with Polish Air Force. Among them was the highest scoring pilot in the Battle of Britain. He was, his, he was Polish by nationality but he was born Czech

CB: Ah

AJ: So his nationality was actually Czechoslovakian,

CB: Yeah

AJ: But he was Polish

CB: Polish born

AJ: Citizen

CB: Ah, right

AJ: It was flight sergeant Frantisek, he was the highest scoring pilot in the Battle of Britain but we never say he was Polish, he was Czech [laughs]. Unfortunately, he was killed during the battle

CB: So after you were on Blenheims, what did you move to next?

AJ: To Wellingtons

CB: Right

AJ: So, in the RAF, I flew Tiger Moths, Oxfords, Ansons, Blenheim I and IV, Wellington X and XIV, Warwicks and DC-3s. The DC-3 was mainly in Transport Command conversion unit

CB: Right

AJ: That was all. We were due to fly DC-3s in India but

CB: Ah, so you went to conversion unit

AJ: Didn’t happen [laughs]

CB: Now, you were all being trained together, in Bomber Command at the OTU, the various specialities were pilot, navigator and so on, were put in a room and they then made a self-selection of a crew, how was your crew put together as Polish people?

AJ: Mainly by sort of knowing each other and for first few months were lectures so it was easy to know the, to become aware of that particular, he must be a good navigator [laughs], so I used to ask him, would you join my crew [laughs]? As exactly my navigator was a lawyer from Krakow University [laughs] and I thought, oh, he’s a lawyer, he must be good navigator [laughs] and he was, he was, unfortunately he was not very healthy

CB: And the crew of the Wellington with six in Bomber Command, in Coastal Command what was the crew numbers? How many people in the crew in Coastal Command?

AJ: In the crew? Six

CB: Right. So, who ran the ASVE? Who ran the ASV Set?

AJ: Sorry, I didn’t

CB: Yeah, you had the airborne radar, the ASVE

AJ: Yes

CB: Who’s job was it to run that?

AJ: Who, radar?

CB: Yeah

AJ: Well, all three radio navigators were trained gunners, radio officers, and radar operators and during the operational flight, they changed every two hours

CB: Right

AJ: They changed rotation, one, two hours in the rear turret, two hours at the radar and two hours at radio station,

CB: And you said that when you went on ops, then they were long and you had extra tanks, what was the nature of the sortie? Would you drive, fly to a long, the farthest point and then do a square search or what did you do?

AJ: We managed to go to the patrol area and then we patrol, mainly box patrol in a certain area, sort of and there was one aircraft operating this sector, the next aircraft, several aircraft was sort of blocking say Western approaches

CB: Right. And what height would you be flying?

AJ: Fifteen hundred feet

CB: Right

AJ: We were flying at fifteen hundred feet mainly

CB: So, how often did you use your armament when you were on ops?