Interview with Donald Keith Fraser, One

Title

Interview with Donald Keith Fraser, One

Description

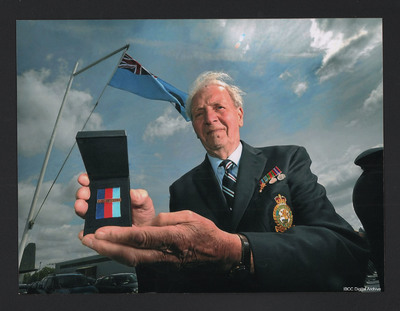

Donald Fraser grew up in Fifeshire, and worked in forestry until he volunteered into the RAF in 1942, aged 18. He trained as a flight engineer and completed a tour of operations with 101 Squadron. He recalls operations to Berlin; being hit by anti-aircraft fire; how the mid upper gunner tried to jump from the aircraft; and landing in the wrong airfield in the fog. After he completed his tour he became an instructor and, before he was demobbed, he was offered a commission but decided to return to forestry work. He talks extensively about his career working in forestry until his retirement in his 80s and about meeting up with some of his crew 70 years after the war.

Creator

Date

2016-11-04

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:59:40 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AFraserDK161104

Transcription

CB: My name is Chris Brockbank and today is the fourth of November two thousand and sixteen and we’re with Donald Fraser in Whitchurch in Shropshire to talk about his life and times particularly in the RAF. So, Donald what are the first things that you remember in life?

DF: I was born on the twenty fourth of August 1923, at a small place in Fifeshire called Kincardine-on-Forth. We stayed there, my Father was a gamekeeper along with two of his brothers who had come through the First World War and they took on game keeping as their career afterwards. We were there for two years and moved from there, he got, he had head keepers in an estate in Fifeshire, Moray estates, in order to earn more money and he was head forester there. Unfortunately, he was killed by lightning and I was six-year-old, the family at that time was, I had an older brother and sister and the younger two sisters, so there was five in the family, and he was killed on January the tenth, roundabout there, it be 1911 or something, which meant that, it was sad for the family because at that time there wasn’t the same facilities to get at that time. So, Moray estates were very good, they gave my Mother a house in Aberdour, and she stayed there all her life, but it meant [emphasis] that at the age of eight I used to deliver milk in the mornings [laughs] horse, horse and cart and the same in the evenings, in the summer time, and then when I became eleven, I could no longer do that by the same horse and cart, so I joined the cooperative who delivered the milk at half past six in the morning, so I still had time to do delivery before we went to school, and at weekends we used to do delivering groceries and that for the coop, they also, it was interesting because we were in the, the scouts at that time, and the scout leader was a Mr Fisk who had a large house in Aberdour, and he used to invite some of the scouts to go down in the evenings and weekends to do work in his garden. We got four pence an hour it was in old money, four pence an hour and we got that when we’d enough money to make a pound, which took about sixty hours to get a pound. [laughs] So, I joined school going to Aberdour school, and then at the age of eleven, it was two schools, there was Dunfermline school which if you were taking languages you went there, if not you went to tech log school at Burntisland, one was seven miles away to the west and then it was four miles to the east, so we went there and that. I enjoyed school, school was good and I was usually first or second in the class on maths and technical subjects all the time I was at school, however the school people wanted us to go onto university but that wasn’t on [unclear] so I applied, the situation at that time was very similar to it is now, there wasn’t many applications, there wasn’t many jobs available but I was interested in forestry and trees, and also in mechanics, so I applied to a company in Kirkcaldy to see if there was a vacancy in mechanics, there wasn’t, but I also applied to Moray estates and there was a vacancy as a forestry personnel on the estate, so I took that up and of course I stayed there until I joined the RAF. It was interesting and just what I wanted to do and the staff there was two older men who had a lot of knowledge in forestry and they gave us a good insight onto what was happening, and Moray estates it was just on the south, [laughs] north side of the Firth of Forth, and there they had Donibristle House which was always kept fully organised in case they ever wanted to come back there, they only came once or twice a year but all the staff was there all the time, St Colme’s House where all the information was kept on the estate, and in Aberdour opposite the only really good hotel was the large entrance to the [pause] driveway into the estate itself, marvellous entrance for that and it still stands today and that, so that was that

[Tascam noise]

DF: My, because of my age I was a little bit in front of the other people and I went to school that sort of, almost a year earlier which meant that to join the forces, all the ones I was with, was leaving early because I was that little bit, my brother was eighteen months older than me and I was in the same class as him, and so the time came and we were all leaving to go to the forces whatever it was and people used to start asking, ‘why aren’t you going?’ you know, [laughs] not realising we were younger at the time. So, I volunteered for flying duties with the RAF and had the usual examinations and such, I was given the opportunity to start training as a flight engineer because of my, what I said, my mechanical interests, and that was in 19, July 1942. Again, we, our first call on joining was Blackpool, we went to Blackpool and there we stayed for almost a year because we done the mechanics course and then we carried on to be a fitter’s course. Blackpool was a marvellous place to be, really is, the tower was still open and so was the Winter Gardens they were still open at that time, and lower floors not the top floors and so it was interesting to be there. We used to have bath nights twice a year, I think there was about ten thousand RAF people there at the time, and twice a week you had to come in the evenings and join up to go in for a bath or it was a shower in fact, and that happened twice a week from all the different site places in there, and to get to the baths, and it was one of these quick things, in and out [laughs] and that, and we were stationed Montague Street which was in the south, south shore, and we used to do our training at the [pause]

SF: Amusement, amusement park

DF: At the amusement park which is still there today, and we used to do all the training in there, and we used to go by buses from there, out to a small airfield south of Blackpool, which had been [unclear] been turned into areas for training, and we done our training there, and we used to be run back morning and night, on buses, and the landlady was foreign in our house, and she had to supply our breakfast and an evening meal and they were very good, and they used to make me with the same landlady for a year, so we must have done something right. [pause] After Blackpool we went to St Athans to do our flight engineers course, which was supposed to be a six weeks course. When we got there, we were told it was a two weeks course because they were so short of engineers, they had to put us through, so we were doing a twelve-hour day, and it only took a fortnight to get through that, but and then we went to Lindholme, and when we reached Lindholme there were only one aircraft and that wasn’t a Lancaster it was a Halifax, that’s the only time we’d seen or been inside the aircraft. So, we reached Lindholme our crew was already there and they’d been there for quite some time, to go through the usual rules and regulations to be able to fly the heavy aircraft, and we were crewed up with a WL Evans crew, and I remember him, a way of obtaining these people, engineers and all that was everybody was put in a room and there was the pilots there because it was the engineers they were looking for, and the engineers was a case of, you like me and such like, well it must have been that their eyes met and I think that was how [laughs] we joined their crew, in fact he said that he was given instructions from his crew that he had to be back but he had to be bringing a Scottish person back [laughs] and then we done, I had done five hours, five hours flying time when we reached the squadron, 101 Squadron and that was mid-July 1943. Unfortunately, on the way between the, there was two crews with the name of Evans going to the 101 Squadron at the same time, there were sixty crews going but two of them had the name of Evans, AH Evans and WL Evans, and when we reached the squadron, I for some unknown reason was crewed with AH Evans instead of WL, and they asked what we wanted to do and we hadn’t done any flying so it didn’t matter, after a little we said we’ll just leave it and we’ll go with AH Evans, but the other pilot Wally Evans said, ‘no that’s not your, you’re our crew, and you are going to be flying with us,’ so that’s changing all the paperwork, and that’s what happened

[laughter]

DF: We went on our first and second operation the two, the two crews together and the third one we came back but they didn’t, [pause] and that was more or less, I don’t know how you, how you take that, but it was luck or what it was but we are still here today and the other crew, that was how close it was you know, these days, and we stayed on at Ludford, it took us from July forty three until March forty four to do our tour of ops, thirty operations. Now, do you want anything on, on the operations itself?

CB: Yes, what, the useful thing is to know how the crew gelled?

DF: Oh yeah

CB: How you worked and what ever happened on your operations, because thirty is a lot of operations to have done

DF: It is a lot yeah, but well, somehow we were a very good crew, we all gelled together and I never had a glass of beer all the time I was on the station, I said, I not gonna drink at all until we’re finished, funny enough our bomb aimer was the same, he said he wouldn’t drink, so the two of us, the two of us were non-drinkers, but we decided that if we were going to get through we had to work as a team and a certain thing in any team, you’ve got your medal man, whatever you want to call them, and we decided that we should have somebody that could take over the pilots job, somebody could take over the engineer’s and the wireless operator was the difficult one because it was one of these ones that you didn’t get many people who knew the wireless operators job anyway. So, it was decided that the inflight engineer, I would do as far as I could get training, and that’s where we’re talking about the link training, get training on that and so we could fly the aircraft and bring it in if necessary, only, the bomb aimer had started as a navigator but he was ill for a time so he come off that and he came back in as a bomb aimer, so he had the basic treatment and that, on navigation somewhere, he decided that he’d be the one that would take over the navigation. The gunners that didn’t partake as far as the flying the aircraft, well they were surplus to requirement, [laughs] and the bomb aimer also took over the engineer’s job if necessary so we had a people who could switch from one to the other, to keep the, as far as possible, and it worked, it worked very well really, we done a lot of training, I don’t know what the training is, done training and that and everybody, we done what was necessary, we used to when we went to the briefing, we normally, we went there and after the briefing the navigator and that went to do their necessary things, but asked that we went along with them so as we knew the route, and if it was possible on a very clear night, if there’s any objects that we could give as information to, to the crews, there was a navigator such as a right bend on the river was at an angle, something that was obvious you could find out, you used to say well we are just passing so and so now which gave a little bit in the occasion we were on line, where we were and that helped us I think. The other thing was, we decided that we were not there to shoot down fighters, our job was to get to the target and back again, so our gunners was not to fire unless they were being fired on, and during a complete tour never once did our gunners fire at anything for all the thirty operations. We had some narrow escapes, I think the, which we would call part trips which meant we got them back again without any difficulty and we had probably half a dozen raids, other ones would probably get shot up going over, actually we done twelve operations to Berlin out of thirty so we had a good go at the Germans on this, and to most people that was the most dangerous target to be on, especially for the time and all that, but we found that if we could keep putting in the middle of the formation we were safe, it was the stragglers that got out to the side were surely caught by the fighters or the Ack Ack. On many occasions we had one or two big holes in us but not to do a lot of damage, I think it was on our twelfth operation and we ended up in a large thunderstorm and of course you had to go through them, you couldn’t dive out from it and that, you had to go straight through, and at one time we were at twenty thousand feet, the next minute we were down to about four thousand that was how the, the affected us, and round the, inside the aircraft was all the little electric jumping across from side to side and that, and it was quite difficult the fact that it took the two of us, myself and the pilot, to pull us out of the dive we got in, but we managed it about four thousand feet, that was one of the not so nice times. On our twenty first, again to Berlin, we got hit just going into the target by Ack Ack, we had a fire in our starboard inner engine and all our communications went. One of my jobs was to always look out, out for the gunners and if you’re looking back through the aircraft you could see if the guns were working or not, and this time the mid upper guns wasn’t, it was just silent and just lying in the one situation, so I decided after I looked over at the engines, switched off the engine and that, to go back and see what was happening. So, on the way through I collected a portable oxygen bottle and my torch, went back and as I went past the navigator, not the navigator, the wireless operator, I gave him a touch and pointed back, he came back with us and as we reached the middle of the aircraft, here was our upper gunner just get his hands on the rear door, he was just going out without any parachute or any at all, so it seemed to make a lot of sense and took the two of us up all our time to manage to stop him so, getting the door open, however we did and we got him onto the rest bed in the aircraft and he was okay after that, although he was off ops the next morning, he just disappeared from the station, that was one of the bad nights. The other, very bad one I think was, we were caught, it was the seventeenth of December 1943, it was again [laughs] Berlin and this was supposed to be the easiest flight that we’d ever have, [unclear] the weather was just right, there was a heavy fog over the Netherlands, and when we got to Berlin there was just a nice opening where we could drop bombs, turn and come straight back, so it was a straight in and straight out, which meant of course you only got fuel to do that, so it was I think it was a six inch, six hour trip, which meant thirteen, fourteen gallons of fuel, they hadn’t given you any leeway at all. Anyway, when we started off, when we got to the Dutch coast it was bright moonlight

CB: Ah

DF: And instead of fighters, the air fighters mainly on the ground, were all flying, and I think going out to Berlin there was about fifty aircraft that was shot down, we got to, near Berlin and the weather was thick, completely different to what we’d been told, anyway we bombed and on the way back we had a contact from base saying, ‘we were under thick fog, all United Kingdom, east coast was under thick fog, make your way north to Hull,’ didn’t tell us where to go in Hull, just make your way north to Hull, which we did, and the, as we were going along the bomb aimer shouted out, ‘look out I just passed a barrage balloon.’ So, we thought at first that they’d forgot to take them down, so we decided we’d better go inland off the coast in case there’s any more high up still on the coast line, so we turned round and luckily these beacons, controlled beacons, there was two in that area and one of them came on and said, ‘we’ve found you, we know where you are but we can’t see you,’ and the other one said, ‘well, you must be very close to us because you’re very loud, do you want us to put up a searchlight?’ We reported and said, ‘that would be good,’ which they did, but instead of going up in the air it went along the ground, and the first thing the pilot and myself saw was a double storied farm building just in front of us and it must have been just one of these things that happened. So, the, it meant that we were in a few feet of the ground, so it was, in fact it took the two of us to pull, luckily, we were running with a control booster on, normally you wouldn’t if you’re trying to save fuel you wouldn’t, but for some unknown reason I had it on and the aircraft didn’t splutter it just gradually went up and we managed it just like taking a horse over a high jump, managed to just get it over, and the report from the, the rear gunner and this was afterwards not at the time, he had written for some other booklet they was, but he saw, because he was looking back instead of above, what he saw was chickens running from the coop [laughs] in the farmyard [laughs]

[laughter]

DF: And he was pressed over his guns because of the building up [laughter] and we caught our rear wheel on the gate as we were, [laughs] we went through so we decided that we knew then how high we were

[laughter]

DF: So, we decided we’d go back to base rather than play around because we’d probably pick up some better information there, probably get a lucky break, so we went back again and as we’re going along the bomb aimer shouted out, ‘oh I’ve found a, I’ve found the café that we usually go for a coffee in the mornings,’ so that was good, they said well your just, just below us, so we thought well if we turn we’ll get on to the outer ring of the lights, you know, about three miles out we were of the outer ring and airfield, so we got there but flying then about two, two hundred feet but there, the airfield was so close that they were overlapping

CB: Yeah, yeah

DF: So, we came round here thinking we were going to go into our own airfield, somehow we missed that and we kept on and the, we landed in the end at Wickenby, so we landed, we couldn’t ask permission to land, we landed, we thought we were on our own field, the people said, ‘you haven’t landed here where are you?’ You know, so we both looked at each other and thought we’re on the ground aren’t we, [laughs] and then we heard a second voice come on saying, ’this is Wickenby we think somethings landed on our airfield, we can’t see you the fogs so thick, stay where you are and we’ll be with you sometime when we can pick you up,’ and about half an hour later they came and we were on their ground, we got a nights, had some, what do you call it? [pause] meal at that time and we stayed the night there.

[paper rustling]

DF: In the morning [inaudible] tea, got mess there or something. We had a few holes but not too bad so we decided we’d be alright and safe to take it home to Ludford, anyway we tried to start the engines up, they did, they started up, they ran for about anything from two or three minutes and then they all one by one they faded away that was

[unclear whispering]

DF: End up there, [unclear] anyway that was the worst one I think, after that I don’t think we had many bad ones but the case may as you say we had good ones but in that case some bad ones. So, we finished our tour of operations in March 1944 and we’d done our thirty operations, in fact we’d done thirty-one, one was taken as an abortion but we had dropped our bombs on an air plant in Belgium and after when I looked at our operations I decided that would count as one, so if we hadn’t have been counted we had to make the thirty up, we’d have been on the Nuremburg one the following night, so we were lucky. [pause] The crews just, we just parted at that time and until the end of the war we hadn’t any contact with each other at all, but that’s another story, we did find out for some of the crew the time afterwards. But, anyway I was posted to Lindholme to do instructing, but before starting that I went on an instructors course and got an A1 pass, and I went back there, and that were just before D Day and at that time we didn’t know what was happening, but all the, these aircraft that were used for training on was bombed up, but there was only two people as a crew, pilot and engineer, we didn’t know what it was about, and the two of us that was on the crew was, we found out afterwards, that if anything had gone wrong on the landings, that these aircraft would have been used to drop their bombs on whatever was necessary at that time and it was said that we’d have to drop out, bail out before any plane whatever it was necessary, and coming out before it hit the ground, obviously I don’t think we’d have survived, anyway, you wouldn’t survive at two thousand feet, but that was what was happening at that time, luckily it wasn’t necessary, so we didn’t, didn’t go, the bomb was unloaded later on. And, then we, then moved from Lindholme to Cottesmore, no sorry, Bottesford, Bottesford first, and this was August 1943, and as I said before, I was twenty one on the twenty first of August, and we’d just been there for a week and this was our first night out, we decided to have a run round and see what the countryside was like and there was three of us who went that time there was a Jack Molton who up until a few years ago, we were still met each other up, and another person from Scotland he was Jock, Jock Wright, and when we got to Bottesford we were just on, just off the A1 road, and when we got down to, on the main road we decided to, instead of going left to Newark where you go right to Sleaford it took us, so we travelled along there for three or four miles and there was a sign to Marston on the left hand side, well there wasn’t a sign it was just a road in there, and we decided to go down there, and that’s where we made it down to a little place called Marston and there was a pub just on the corner, and that was the first drink I had from joining the RAF, [pause] and after that we seemed to make that our common meeting place. Bottesford was a nice easy going place compared with what we had just been through, and enjoyed our time there training up the other people coming through, and of course VE Day came at the same time we were there, and I was at Buckingham Palace on VE day in London receiving a medal, it was, went down on, my Mother and sister, and my sister Jane they, they came down from Scotland, I met them on the train at Grantham and we went into London, and I think I remember eleven o’clock was the time when we, it was the King at that time of course and everything was over by, just after lunchtime, but my first time in London was [laughs] all in happy moods and that, and my Mother and them stayed in London because we were booked in for that night and I came home on the train late, must have been early evening, back to Grantham and Sylvie was going to meet me there on a bike, but what, what happened is that Marston was a mile off the main road and then you had the main A1 road to London, London that way and north that way, and she was going to bring the bike and pick me up at the end of the lane, anyway she’d asked somebody who worked in Grantham if they had seen an airman walking, and they said no, there wasn’t any airman, and she’d seen one of the lorries with the back open and quite a lot of airmen on it and when they passed her they gave her a normal wave and all this, you know, so she thought that I had got the transport to road end was going home to Bottesford to change and then come back down again, so she came back home, but half an hour, three quarters of an hour after that, her sister get when she was looking out the window said, ‘oh Jock’s,’ I was Jock at that time, ‘Jocks coming down the road there, Sylvie, Jocks coming down the road there,’ and she said, ‘no [emphasis] he can’t be,’ it was, I’d walked all the way from Grantham. [laughs] That was VE day

CB: Right, let’s stop there for a mo.

[interview paused]

CB: Now Donald as you were 101 Squadron, then you were the eighth, you had the eighth man, so who was he and what did he do and how did you link with him?

DF: Yes, our eighth man was part of the crew, he joined us on the first night that ABC was being used, I’ll have to come back to his name

CB: Yeah

DF: But he, he sat just behind the navigator on the Lanc where normally would be the bed for people getting injured and that, and his place was there, and he worked from there, he was just one of the crew, that’s all, we, we had using his [pause]

CB: So, ABC stood for?

DF: ABC

CB: Airborne Cigar

DF: Airborne Cigar

CB: Yeah

DF: Yes, that’s right and

CB: His job, what was his role?

DF: His role was to jam the German night fighters from contact with the ground with instructions, and he done this by jamming on a certain band, outside on the Lancaster was two long spikes, down the way, one in front of the aircraft and one halfway down, and this was his means of contact, and he jammed night fighters, he could speak a little bit of German but he could understand German, and he just jammed the night fighters from that. Unfortunately, by doing that he left the aircraft, the one he was on, the aircraft so they could be contacted by the German fighters that wasn’t involved in that time, and I would, probably the heaviest losses of Bomber Command

CB: Because, in essence, his transmission created a magnet for the night fighter

DF: That’s right

CB: Which was able to lock onto it, was that right?

DF: Yes, they could lock on to us, but we, we were, say on a squadron with twenty-one aircraft on that night, and got the time going through the clouds, save us twenty minutes would be all going well, on 101 Squadron, every minute along the route of covering

CB: Oh right

DF: Of covering the band going to the target, didn’t always work that way because you can’t get people to navigate to that degree in that night, but that was the obvious thing, it was to cover the whole time that they were in the air, and afterwards of course, the squad er, Bomber Command didn’t fly without 101 being there, so we, we had to do a lot more raids and operations than the other squadrons to keep that

CB: And, it was because it was so easy to detect a 101 Squadron Lancaster, that the losses were higher, is that what you’re saying?

DF: That’s right

CB: Right

DF: Much higher than

CB: Now, what did he actually do?

DF: What did he do?

CB: Hmm

DF: He listened for the German ground crews contacting their air fighters, and he jammed that by using the noise from the engines to do it, and he just jammed the

CB: So, there was a microphone in one of the engines, which one was that?

DF: The starboard inner I think it was, and that’s, so that’s what happened, [laughs] but it worked very well for a time and then of course like everything else it, well [emphasis] it was used throughout the war even on VE Day and all that was used, but generally speaking it done some good at times

CB: So, as the flight engineer, you had other things to look after that were electronic, what about your rear scanning detector Monica, how, what did that do and what did you do about it?

DF: Well, we didn’t have Monica on 101, they talked about it and decided that it wasn’t for 101 they would rather be without it, rightly or wrongly but that was, we had the usual, the others, the usual ones that, what do you call it? the little six-inch strips of metal

CB: Oh yeah

DF: [inaudible]

CB: Oh yeah so you had Window

DF: We had Window

CB: And you had H2S or not?

DF: We had H2S, yes

CB: But no other detectors?

DF: No, not really

CB: Right, because Monica had the same problem

DF: That’s right

CB: Of identifying you and that’s why they didn’t want it, was it?

DF: That’s why we didn’t have enough to carry on with

CB: So, just quickly with your special ops man, how, where, was, how did he integrate with the crew and where was he accommodated?

DF: He was accommodated in a little cubby, coming down here, that’s your navigator, here was the wireless operator, he was the next one down there just in there, same as they had, just a desk and that in there, and that was where, on most of the aircraft, was the bed, the, what do you call the bed now?

CB: Yeah

DF: The resting bed

CB: The resting bed

DF: Was there, so it was taken out and his little cubby hole was put in there

CB: Right. And on the ground, was he in your nissen hut or was he somewhere else?

DF: No, he wasn’t in a nissen hut he was somewhere else

CB: And why was that?

DF: I don’t know, they seemed to keep them apart

CB: Hmm, one suggestion was that if they talked in their sleep

DF: Well, I was going to say, one suggestion was that, if they talked in their sleep it might cause some problems, but we had, we didn’t change our one, we had the same person all the time

CB: So, in a social context when you went out as a crew, did he join you?

DF: He joined us at times, yep, which was, I think better than helped to gel the crew together

CB: And what were the ranks in the crew? Were there all NCO’s or was there an officer?

DF: To start with all NCO’s, after about probably seven or eight, the pilot was upgraded to [pause] pilot officer and such like, and I think he was, no he wasn’t squadron leader, he was lieutenant when the crew was finished

CB: At the end of the tour?

DF: End of the tour, yes, he was the only one

CB: Okay

DF: That was commissioned in that time. We were asked afterwards but I went to fly in the RAF not to sit at a desk and such like

CB: So, how did your ranking go during the war time?

DF: The ranking, I came in as a warrant officer, so ended up as a sergeant, flight sergeant, warrant officer and I remember having an interview with the CO of the, what do you call it?, North Luff, Luffenham airfield just before you were demobbed, wondering if we wanted to stay in the RAF, and he gave us some indication of what could happen, at that time they were very short of engineers, ground engineers and funny enough during the time when I was at Cottesmore and that, I had plenty free time so I took on doing the ground engineer’s exam, and I was probably the only aircrew personnel that ever took it, and I got a rating of eighty one percent, so when I came for an interview, whether wanted to stay on or leave, he bought this up and of course I still said I wanted to go back to civvy street, but they promised probably lieutenant or squadron leader or eventually, or another thing we were interested in was the flying and the, the business side of it, the British Airways which at that time was only from Assyria to India somewhere like, which was not much [unclear] so we decided to come out and take up forestry again

CB: Fast backwards to your Berlin raid, there were all sorts of challenges on the battle of Berlin, er, what about searchlights, how often did you and was there any particular incident that was noteworthy?

DF: There was only one as I say, the blue searchlights that was the one that was the main, we had been caught once or twice with other searchlights, they didn’t cause us much damage

CB: So, what happened on this occasion?

DF: Well, as I was saying, we were caught in searchlights, and if you are caught, there’s three of them usually at a time, if you run out of this one the next one caught you and so on, so you were just held in it all the time, and as I say, rays worked in conjunction with the Ack Ack’s, if you were held long enough the guns could pick you off, and that’s what happened to quite a lot of people, we were lucky that somebody below us took

CB: So, what happened, instead of you what else happened?

DF: It was a Halifax aircraft, it was travelling below us, they never reached the same elevation as Lancasters, and all of a sudden it just blew out the sky, it was caught by, we think was [unclear]

CB: What were the relative heights that day?

DF: They would have been about eighteen thousand, we probably about twenty, twenty-one, the distance in travel on two aircraft

CB: And how many of the crew actually saw that incident?

DF: The gunners, myself, that would be all I think, yeah

CB: Right

DF: We reported it on of course on our debriefing afterwards

CB: You talked about the end of the operation, you were awarded the DFM, how was that communicated to you and how did you feel about it?

DF: I don’t think it was communicated to us, I think the first we knew about it was

[Tascam noise]

DF: When we got it in writing saying you had received it, the DFM and would we go to Buckingham Palace on the date, we didn’t know of course it was VE Day at that time, but that was the first, I was quite pleased with what was happening with, we didn’t even know at that time whether the whole crew had got it or not until later on

CB: So, this, this wasn’t at the end of your operational tour at all?

DF: No, no, it came

CB: How much later was that? Where were you at the time?

DF: I think we were at Cottesmore, it must be about, must have been about six months later anyway, at least that

CB: So, you finished your tour erm, in forty-four, middle of forty-four

DF: Yeah, yeah

CB: Then you went to Lindholme

DF: Yeah

CB: Then you went to Bottesford

DF: That’s right

CB: So, how was that working, that at Lindholme you went to Bottesford

DF: Yes, Lindholme

CB: For what reason?

DF: Well, the tour doing [unclear] at Bottesford, as I say went to Lindholme and from there I did this instructor’s course, and then was posted straight when we came back from that to Bottesford. Bottesford before that had been a Lancaster airfield, but it had also been used on D Day by the Americans, and it was in such a mess, it was windows out and all the holes of the firing through the roof and all that sort of thing, I think it was just them they bought and went

CB: What before they left they?

DF: Before they left

CB: So, what were they using the airfield for exactly?

DF: A holding point for the Americans before they went on the D Day landings

CB: The troops?

DF: The troops, yeah

CB: Right

DF: Yeah

CB: So, that was a bit disruptive?

DF: It was

CB: And the crews who you were training at Bottesford, where did they go next?

DF: They went to wherever the casualties were

CB: It was a, it was an OTU was it?

DF: It was a heavy

CB: Conversion

DF: Conversion, yes

CB: Heavy Conversion Unit, right okay

DF: So, they went to the squadrons which were, was requiring aircraft

CB: Right, okay, good. So, you were there until after the, after VE Day?

DF: Yes, and then we went to, after that we went to Cottesmore

CB: Hmm, hmm. What did you go there for?

DF: The same thing, it was just more or less, seemed to be a transfer, Bottesford was a wartime drome, it was closing down

CB: Yeah

DF: So, we went in Bottesford, went to Cottesmore

CB: Yeah

DF: Which was a, which was a

CB: An expansion period airfield

DF: Yeah

CB: Yeah

DF: And after that we went to North Luffenham

CB: Hmm

DF: Didn’t, time, didn’t spend much time at Cottesmore, then we moved on to Luffenham

CB: Another expansion period airfield

DF: That’s right where ever this, was demobbed from there in 19, end of 1946 that was

CB: So, where were you actually demobbed from?

DF: From, some place in London, [pause] somewhere near Paddington, I can’t remember, but it was a London address, I can’t remember

CB: Okay. Right, so you knew you were going to be demobbed in, well in advance, how much notice did you have?

DF: Well, we didn’t have a lot of notice, say, probably knew about a month beforehand, but prior to that what we had been crewed up to go to the Far East with

CB: Tiger Force

DF: Tiger Force, and we were getting ready for going on the week it was VE Day

CB: VJ Day

DF: It was cancelled

CB: Hmm

DF: So, we didn’t go

CB: Right

DF: Luckily. We’d done our training, we used to train on the, on the Trent, going down with a below the levels, but the Lancaster, below the lower levels that are the size of the Trent

CB: What planes were you training on then?

DF: Still Lancasters

CB: Still Lancasters

DF: But we could get it below the levels, bank levels [laughs]

CB: Yeah

DF: It was just flight engineer and the pilot, just the two

CB: Oh right, just the two?

DF: Yeah, I think it was a bit of

CB: Bravado, was it?

DF: [laughs]

CB: Needed a bit of excitement after everything else?

DF: I think, I think that’s true, but it was also a good way of training for what we might be up against with going out there, nothing about it

CB: So, after VJ day, it’s, that’s still some time before you were demobbed, so what did you do then?

DF: We were still doing training, training was kept going but the, the length of training was, well it was just a five-day week at that time, but what we did was to keep the students employed, we had one old aircraft and we, it was working, the engine was working, so we got the students to dismantle the four engines, I think there was about twenty students, there was five on each, dismantled the engine and had to put it back again, they had to run with [unclear] and that was just kept them going for another month or so, extended the time they were on the unit

CB: So, you had the opportunity of staying on

DF: Yes

CB: And er, what was the offer?

DF: The offer was if we stayed on, we could go in as, we’d get a commission and eventually we could possibly reach the grade of squadron leader, I think that what was said

CB: But, you wanted to do what?

DF: I wanted to go back to forestry. So, we demobbed and we went back to our home in Aberdour, we didn’t, it was only for about a fortnight, before that I had been in contact with the, prior to going into the forces when I was eighteen, I’d been in touch with the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh, to see about becoming a probationer however, the probationers then was only for gardeners sons, and they could become a probationer, and then they done the full course that you do in the university better then on time, they usually do it in the evening, classes and that it, it’s different from going to university and they done the work in the botanics during the day, but they wouldn’t take me because I wasn’t a son of a gardener, however after the war we tried again and by this time we had some very good friends, one who was the scout master as I said, but he was also in the Scottish, Scottish office during the war, he spent a lot of time in Edinburgh, and he got to know one of the professors in the botanic gardens, and I asked him if he could do anything to help us, which he did, and after being demobbed, for, I think about three weeks, we joined the Royal Botanic Gardens as a probationer. [laughs] One of the highlights of that was, at this time, it’s coming off this altogether, but there was a tree forgotten tree, a lost tree Metasequoia, which botanists from China in 1939 had found just the remains of this tree, had been lost for a century or something like that, and he was going to go back out again and see if he could find anymore but the Chinese, he was Chinese, Chinese obviously during the wartime didn’t have any money or anything to do, so he had said he’d seen it in 1939. In 1944, the Americans decided that they would put, give them money to go out back again to see if he could find it, which they did, and he found the tree and collected seeds from it, the seeds went as normally to various botanic gardens throughout the world, and then the UK, twelve seeds came to Edinburgh University, twelve to Cambridge and twelve to Kew, and I was at the botanic gardens in Edinburgh at that time and I got the opportunity to sow these twelve seeds, and now there’s millions of the trees growing, they were propagated afterwards from cuttings and that, so that was one of the major things I think in that [laughs]

CB: So, that’s in Edinburgh

DF: That’s in Edinburgh

CB: Where you were a probationer

DF: Yeah

CB: How long did you do that?

DF: We, we, the idea was to be a probationer and then either go to the rubber or the tea plantations abroad, or if there was any good jobs going in the UK, take that on, the difficulty in that, that the colonies didn’t want the British people after the war, they were doing it all themselves, so that sort of fell through. In the meantime, the Forestry Commission research branch, and it was a mister [pause]

SF: Edwards, was it?

DF: No, [pause] the one before that [pause] anyway he, he was Scottish research officer for the Forestry Commission, and he came in to the botanics one day when I was there, and when you started botanics you had to do a project, the project that I took to do, I had been looking at [unclear] books from the forestry on that and the Christmas trees at that time were in demand, but they had a problem because it was Norway spruce they used, and generally speaking in the spring, those trees got frost damage which spoiled them, but I found it was two different types of trees, one that flushed early and one that flushed later, and what I done when I got to the botanics, I got two thousand cuttings from each type of tree and planted them in pots, and it was when he came there he saw all these pots lying there and said, ‘what’s going on here?’

[phone rings]

DF: He said, ‘oh let’s [inaudible]

[interview paused]

CB: Story there, so you, you were interrupted by the phone

DF: Yeah

CB: Yeah

DF: So, we had these ready cuttings all in

CB: In pots, yeah

SF: [talking on phone]

DF: He came along and said, ‘what’s going on here?’ and one of the other probationers said, ‘well you’d better ask Donald, he’s across there, he’ll tell you,’ so I told him what we were doing, you know, and said, ‘well, do you want to go into research?’ I said, ‘well, I’ll have to think about it,’ he said, ‘well, we’re at the moment looking for people to come and into the Forestry Commission research, we want to increase it after, we done it after the first World War, and the second World War we are going to [unclear] going to increase the whole policy in forestry, we are going to build up more planting then,’ and I said, ‘well give me time to think,’ so we did take another three month and he came in again and said, ‘well if you wish you can start with us anytime you want,’ I said, ‘what’s the duty like?’ ‘good,’ so we left the botanics and joined them, and the first job I was then, was on the [unclear] department, which was travelling the country picking out various plantations of trees, different ages, measuring them up and getting a volume, which was going to be used for all the tables for the future

SF: [inaudible whispering]

DF: So, we measured all the trees up, we used to do that in the summer and then in the winter we used to go back to the office and work out all this, and these tables are still used today

[background noise, cups rattling]

DF: And, about the cuttings, they were sufficient survived and they were by the Forestry Commission and they were planted in a forest in south Scotland, and last I heard about

[loud cup rattling]

CB: [whispers] I’ll do it

DF: Was that

CB: [whispers] Keep talking

[cups rattling]

DF: In 1995

[loud crash and smash]

DF: They were growing and had reached the height of a hundred feet

[loud footsteps]

SF: Thank you

DF: They’d been planted in twenty-five groups, like a chequer board, twenty-five trees in each group, and the last I heard was as I say, in 1995 was still growing, you could still see the chequered in the air in the south forest

[kettle boiling]

CB: So, this was a beginning of a glittering career for you?

DF: It was

CB: So, where did you move from? In the Forestry Commission they moved you about, to where?

DF: In the Forestry Commission, they well, we didn’t move very far, in the Forestry, this I done forty seven, forty eight until we, as I said, we married in 1948, August seven 1948, and after that I asked for a transfer back to a base, and I was given Tulliallan, now Tulliallan is the same place as where I was born I was born in Tulliallan in some, in 1923, and also at that time the manager of Tulliallan nursery was a Mr Simpson and he bought the chickens and hens that my Father sold to him before he left there to go into Fife, now it becomes rather personal this because eventually, we went back to Tulliallan and then

[phone rings continually]

DF: Mr Simpson had been manager of this nursery and acres nursery when he came out the first World War, now at that time

[laughter]

[phone ceases ringing]

DF: The research, here Mr Simpson was the old type of person and he didn’t think that people should have been not in the war at all, his, his son was an objector to it, so when anybody came round there, all his junior staff was people who hadn’t been during the war, in forestry itself was people that had never been, so when research started there, when they went to ask him for something, he just said, no you can’t do this, I’m not going to do that, I don’t think you are the right people to do that. Anyway, I went there and at that time it was a, Ferguson was the name of the research forest at that time, and we had a meeting with him, ‘what do you want to do?’ so I said, ‘I want to do research on nurseries,’ and he’d got it all here. He says, ‘I don’t think you’ll manage to do that,’ and I said, ‘why?’, so, ‘Mr Simpson won’t give us any land, he’s just dead against us,’ and I said, ‘whys that?’, and he said, ‘I don’t know I think it’s probably because we’ve never been to the war,’ so I said, ‘well I’ve never been let down by anybody before, I’ll go and see him.’ So, the research people had been there probably six months and I went to see Mr Simpson and went into his office and he said, ‘I suppose you’re another one of these people,’ I said, ‘what people?’ ‘who’ve never been to the war,’ I said, ‘well I am, I have been it was hard,’ ‘what were you doing in the war?’ ‘flying Lancasters,’ and he jumped off his seat, came round and shook our hand [laughs] and he said, ‘I remember a Mr Fraser, twenty odd years ago being in a lodge down there,’ I said, ‘that was my Father,’ and he said, ‘yeah, I bought his chickens from him,’ [laughs] and I went back to, [unclear sentence] I went back to the research people and said, ‘look we can do anything we want and [unclear] go through with it Mr Simpson,’ ‘how did you manage that?’ I said, ‘just by talking to him,’ and that, and we became great friends and he’d never been on holiday since he went there, and this year, that was the year we were there, he wanted to go away for three weeks, and believe it or not, Sylvie and I went into his house, and looked after his house while he took three weeks holiday, they, they couldn’t think at that without, and we were even there, oh we used to go round and see him and after we left there, you know, that on the way to go round from Fife to Edinburgh, if it was very bad weather, was round the road and across the Kincardine Bridge and back round the other side and that, and we used to go round that way and see him. And, this night, what 1970s, we called round and his missus said, [unclear] ‘Arthur is, he’s had a stroke but he won’t allow me to get the doctor,’ she said, ‘I knew you were coming tonight,’ so I said, well we weren’t, we just because we couldn’t get back to [unclear] ‘I knew you were coming,’ so I said, ‘that’s alright I’ll sort him out, so I went down, got the keys for the office, phoned the doctor and then he went to stay in one of the new towns near Kirkcaldy in Fife, and we saw him until the end. After he died, it must have been 1980 odd, we went to see her when she went back to the west of Scotland with her son, was this time but he was still a known objector to the war, so that was that, a funny situation

CB: You’ve raised a really interesting point here, that the business of LMF, which we’ll come back to, but here you have the situation of a conscientious objector

DF: Yes

CB: And the effect on his father. So, what was his father’s attitude to his son?

DF: Not very good, he didn’t, he didn’t go and

CB: Did he disown him or did he simply

DF: Well, he ignored him

CB: Have nothing to do with him?

DF: But, as I say, after we went, that same year he went to see his son and he spent three weeks with him

CB: And he did what?

DF: He spent three weeks with him on holiday

CB: Oh, I see, with him

DF: With him

CB: Yes

DF: Yeah, so we had sort of sorted that out

CB: The reconciliation took place because of your?

DF: Yes

CB: Very touching

DF: It is very touching

CB: Hmm

DF: There we are. So, so anyway we joined the team at Tulliallan, we done the experiments there on various things within the nursery itself on, weed control was one of the main things, the cost of weed control was enormous because you had people sitting on seed beds, months and months in the summer, just pulling up weeds, so we tried different chemicals and that until we got the right one that would do that we also wanted to make sure that we grew a seedling large enough in one year to transplant, line out, transplant it out after one year, at the moment, at that time it was taking three years instead of one year, so we’d get a plant fit for a forest planting, because the Forestry Commission was going to increase a lot. As a one, a two-year-old plant and believe it or not, after so many years we managed it and they cut, well the chemicals and that helped to cut down the whole system and that

CB: Did you then do cross fertilisation how did you manage to?

DF: Well, the cross fertilisation was another part of it, from then I stayed there until we got a house there in 1950, stayed there until 52 and then the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh where I’d been previously, they decided they wanted to do experiments for students on forestry, so this landed me very well, and the Edinburgh university, the university bought a small estate outside Edinburgh, south of Edinburgh called Bush estate, and there was the land where they were bringing all their outside interests together, the veterinary college. The potato industry they were doing [unclear] about potatoes, the horticulture, bee keeping, all the departments at the university had an external department out there, and this forestry also wanted, the university wanted a forestry section there to, so I was posted there as a research forester for south east Scotland, and covered the botanic gardens and the Edinburgh university at the same time. We used to teach the students how to grow trees during the summer and Easter holidays and that, they all had to do so much practical work at that time before you could be, take the course, and then built up relations there, I was there for, too 1971, that’s a long time from 53 to 71. We built up a complete structure of research in that area of south Scotland, as you know south Scotland had probably more

[loud bang]

DF: Dukes and Earls and that, then anywhere in the UK across the borders and that, and they got all them interested in the forestry, and so much so, I think you’re talking about cross pollination and that, one of the things we did during the fifties and sixties was select the best trees in the UK

[sound of footsteps]

DF: And we called them plus trees [pause]

[background noise]

CB: We are just going to pause for a mo.

DF: Bills and all that

AM: Yeah

DF: So, they wouldn’t accept that, funny enough, after time, I used to lecture to the schools

AM: Yeah

DF: [laughs] on forestry and tree breeding and that but they wouldn’t accept

[loud stirring of cups]

DF: The Forestry Commission at our house

[loud bang]

DF: Was down in the New Forest

AM: Yeah

DF: And they used to run courses there every year, and one of the courses was on nursery technique to cover the trade and the Forestry Commission nurseries

[background noise]

DF: And who took the courses? But, me [laughs]

CB: But they didn’t accept you because you didn’t have a university degree?

DF: That’s right

CB: Right, there’s obviously a logic in that, but we don’t know what it is [laughs]

AM: You’re not switched on, are you?

CB: Yes

AM: You’re not switched on?

CB: Yeah, we are

AM: Sorry

CB: Right

DF: So, yes, we went to Bush as we said, it was a covered the whole of

CB: Whole of the UK

DF: The UK

CB: Hmm

DF: And, we had selection for plus trees as we called them, that was the tree which was ten percent

[crockery noise]

DF: Better than the trees round about it in any plantation, the straightness of stem can make it a perfect tree to be ten percent better than the others, and we selected these and put a yellow band around them and then we went back later and collected

[crockery noise]

DF: [unclear] material for grafting from these trees, we grafted these trees onto other plants

Unknown female: [inaudible whispering]

DF: Where we, all this as done for the north of England and that was at Bush nursery, I think, Sylvie helped us and with that, that we used to do a whole day grafting and that, on the nursery, four thousand a year we used to do, and this applied for seed orchards being planted within the UK, but all that grafting was done, and I done the whole lot

CB: Fantastic. Just a final one before we pause again. How did you come to move to the south from Edinburgh?

DF: Well, this is later on. I left the Forestry Commission in 1971.

CB: Yeah

DF: For the same reason as you just said, I wasn’t a UK graduate

CB: Right

DF: And I joined the economic forestry group

CB: Right

DF: Which was the

CB: This er

DF: Largest forester group in Europe as their nursery director

CB: Right, right we’ll stop there now

CB: Because that was a commercial enterprise

DF: That’s right, yeah

CB: Yeah. Okay I’m stopping now

[interview paused]

CB: So, we’re talking about change to a commercial world

DF: Yeah

CB: What was the name of the organisation and how did you come to join that?

DF: The economic forestry group was the name of the organisation [pause]

CB: Yeah, and what did you do? Why did you go there?

[paper rustling]

DF: I fell out with the Forestry Commission research branch after all these years, and the same thing as you were talking about before, not being a university graduate. The northern research station was built in the area of Bush and it was finished in 1969. Now, I’d been running the forestry research in east Scotland for twenty odd years, and people just used to call in as they’re going into Edinburgh if they were wanting any advice and that, and just saw me and went to me again, and the research station came and they bought in all the different people on, what er, entomology, pathology, and bought all these heads of department in and they all had offices in there, but, and the people were coming up from the service when they were meant to research. Reception said, ‘oh can I see Donald,’ and the girl in there said, ‘oh no, but you can see doctor so and so,’ ‘oh I don’t want to see him, when will Donald be in?’

[laughter]

DF: ‘oh he’ll be in tonight,’ you know, ‘oh I’ll give him a ring tonight.’ [laughs] And this happened, and they got so fed up with it in there that, and I also had an office in there, and I had a secretary also, they all had to put the, all their requirements through the, this pool doing the typing and all that, [unclear] so I was getting preferential treatment from everybody, and the head was, was in charge of research at that time and he collared me one day and said, ‘look Don we’ve got a problem here, you are being posted to Perthshire,’ I said, ‘I’m not, what reason? Because I says, ‘there’s no research there,’ ‘no it’s to a unit,’ I said, ‘no I’m not,’ I said, ‘well, I joined the Forestry Commission research branch, I’ve got a note to that effect from JB McDonald when we started, you can’t do that,’ ‘well that’s what’s going to happen,’ and I said, ‘well, if that’s what’s going to happen there’s my resignation there now,’ and I left like that, [laughs] so they didn’t even [laughs]

AM: Bit of a shock

SF: Well it was because Brian was only three, I think it was, and I thought, hmm this is going to be interesting [laughs]

DF: So, anyway the forester group had an office in Edinburgh and we’d been dealing with planning with plants anyway, and we knew them quite well, and I was up there on an interview to become one of their managers, area managers, and we were having this interview and the phone went, and this was their headquarters saying did I know they had a vacancy for a nurseryman to take over their nurseries, running the nurseries, I said, ‘no I hadn’t heard anything about it,’ so they said would you like to

SF: Have an interview for that

DF: Interview on that, and I said, ‘yeah,’ and they said, ‘can you go down to,’ where was it? Just outside

SF: Farnham

DF: No, just below Oxford. I said, ‘yeah, I’ll go down tomorrow,’ so I went down

SF: Oh yes

DF: And had the interview, two days later I got the job and that was the start of it, yeah, but it was a, it was a challenging job because economic forestry group at that time, was doing all the planting, you know you could get grants for planting and all this, and a grant for good one thing was ninety percent of that and

SF: Tax

DF: Tax was more or less you were paying ten p in the pound for your forestry and that, and that’s a lot of people doing it and that, but when I joined them they had all different people growing the plants for them which, we were going to be responsible for giving them the best quality plants at the right price, we had to control all that ourselves, so

[phone rings]

CB: Hang on

DF: So, if we were going to control all

SF: [on phone] Hello, yes

DF: The quality we had we had to have it all in our own hands

SF: [on phone] Yes, I’m here

DF: At that time, they had

SF: [on phone] can you hear me now? Yes, I can hear you

DF: Getting, growing procedures to various nurseries throughout, throughout the country, in the north and Northern Ireland, used to grow seven million for them and the various small companies used to supply them with plants, but to me that wasn’t good enough, we were going to be responsible for that, so within two years, at that time we had two nurseries running forestry, one in Scotland in a little mill just outside Perth and one a mile from here just up the road, and that was the two nurseries that belonged to economic forestry group, then another two that was down in Devizes and then Cambridge, which was used for high quality trees and shrubs for the different markets, so we decided that to stop all the contracts we had with Northern Ireland and Northern Ireland decided to take me to court for breaking contracts, which I said, you can’t have no money so [laughs] that, anyway they dropped that so that was seven million we dropped that to sell. Nurses in the north of Scotland was also growing for us, and we cut all these, increased our own volume in our own nurseries, doubled the size of both nurseries and in the end we were growing, the company was using forty million trees a year and I decided we didn’t want to grow forty million and we grew twenty percent less, so we started growing two million of our own stock which gave us a market still market in the [unclear] if it was a bad year for one species we would still be in the market to get that species from other people, and the, that worked very well. The people that didn’t join us afterwards, used to come to say, ‘what provenances of pine do you want?’, I would say, ‘so and so’, ‘oh’, ‘the next time I orders I’ll get that in case you want them,’ ‘so we will probably want them,’ and when it started before that I used to go to the nurseries and say, ‘have you got any Scots pine?,’ ‘yes,’ ‘what origin?’ [laughs] ‘er what origin do you want?’ and I would say, ‘oh [unclear] for the north west,’ ‘oh that’s what they are,’ ‘come off it, can I see your books?’ [laughs] many times it wasn’t the book they give you the sort you wanted, so afterwards we got known as the person that if you wanted anything, contact me, and it was a responsible thing, because we were responsible for the whole of the UK more or less, had we chosen the wrong provenance or anything of these things it would have been disastrous for the private sector and that, because we were selling plants that were planted by our company for their future, you know, but it worked out well. The only time I used to have to, had the possibility of stopping any planting that was being done, if I didn’t think it was the right provenance for that site, which meant a lot of travelling, we used to do fifty thousand miles a year looking at different sites to make sure that the right species and the right provenance was going on. Scot erm, [unclear] spruce was the main species and that was the one that needed all the rain, but it gave the best quality tree in the end, but there was a range of that available from Oregon up to Alaska, right down the west coast of America which meant that if you got, say trees from Washington, half way up, they were very fast growing, but they couldn’t stand the winter frosts on certain sites, on the other hand if you wanted to, to put them on a high elevation to increase your level of trees, get them from Alaska, and you could plant them there, and of course people at that time, didn’t want to have different species but one species on the site, so they could all get off together, so we used to, at the bottom of the valley, probably only put in plants from Washington, and as you go further up Queen Charlotte Islands and at the top just to get the next twenty feet of growth, these high ones from Alaska and that’s what made the difference between these people making a profit and not making a profit. On the other hand, there’s of course, that once they were selected and that, initially the seed was producing something like fifteen, sixteen percent of quality trees per thousand, after the selections were done, and I was talking about plus trees and all that, but that quality went up to sixty percent, and then when the seed orders came in it went up to eighty percent, so eighty percent of the plants planted on the hillside was becoming timber size instead of sixteen percent a few years back, and that’s what saved the UK

CB: Amazing

DF: It is

CB: The erm, you worked on continuously did you or did you, until what age?

DF: I worked on until, I was still working when I was eighty, eighty odd

CB: Right

DF: And even when I retired I joined Booker, who was in agriculture and forestry and became their advisor on forestry for, until they pulled out in two hundred, two thousand and two, I think it was

CB: During your long career in forestry, what papers or books did you produce in support of the cause?

DF: None in that really, no, it’s all just making profits for the company

CB: Yeah. Can we go back now to the wartime? Your experiences include twelve raids on Berlin which at that time was a very difficult time

DF: Yeah, it used to

CB: How did you, how did you feel about those raids?

DF: Well, it was always said at a few, and this came from an office, used to say us, when you joined them, I think they used to say, ‘what do you intend doing?’ and said, ‘flying for thirty ops,’ and said, ‘you’ll be lucky,’ so I said, ‘why?’ he said, ‘well the normal time here is five weeks,’ I said, ‘oh that’s a lot of nonsense, surely,’ so he said, ‘well, we’ll wait and see, but you’re on Berlin tonight,’ and I said, ‘yeah that’s all alright, you know,’ ‘well, if you do Berlin once, you’ve done alright, if you do it twice, you’ve done very good, you won’t do a third time,’ I said, ‘why?’ ‘nobody’s done a third time,’ I said, ‘well I’ll proper show you,’ and that’s the attitude we took. I, I knew, and that in fairness, but if I could get that airplane off the ground with five or six tons of bombs on board, and standing on that in the aircraft with two hundred gallons of fuel in your wings, if we could get off the ground, we’d come back again, and that happened

CB: You were clearly hit by flak quite a number of times?

DF: Yes, oh we were

CB: Did you get engine out more than once?

DF: We had engines out, two, yeah, I would have to look up the book but probably three or four times, once we had two out on the same side, on the starboard side, but we managed to get down and that, and once our undercarriage got hit and it wouldn’t come down but just by doing that, quite a high pull up, it came down, it locked and that allowed us. These things you [unclear] as you went along

CB: Sure. What were the ways of getting the undercarriage down if the hydraulics didn’t do it?

DF: There was a hand, hand

CB: Was that a pneumatic pump or was it a?

DF: It was a hand, yeah you just pumped it back and forwards and that, it wasn’t a very good way of doing it, but I think we all knew how to use it once and other times

CB: One other time?

DF: Yeah

CB: So what sort of damage, other damage did you get to the aircraft?

DF: Well, we often had our communications cut off, but somehow on three or four occasions I managed to get our intercom going again which was the main thing, because even if our oxygen was gone we could come down to ten, ten thousand feet and cope without oxygen so that was alright, you knew you could, the cables were running inside the aircraft, so you, you could sometimes spot where you could do it, and I always carried extra, whatever we could get, bits of string and wires and all that, very good, join up things and that

CB: So, what sort of repairs did you have to do when you were in the aircraft on, on sorties?

DF: It was only small things like that, you could only do, it means sometimes you would see where there was a break in the pipeline, as long as you knew where the pipes were running and that, that’s one thing we studied correct a lot or the heating to your different persons, I mean the, all the heating went into the, underneath the navigator’s seat, it all came from ducts in the engines to there, and he of course would occasionally turn it off because he got too hot, and the other [laughs] members suffered because of that, but the main thing was the mid upper and rear gunner was to, suffered, because temperatures of minus forty, if their suits didn’t work there was a problem

CB: The heated suits?

DF: The heated suits, yeah

CB: As the engineer, what was your, the aircraft is ready to go, brakes off, gathering speed on the runway, what are you doing as the engineer during that period

DF: Well

CB: As you get airborne?

DF: We, we split that up between the pilot and myself

CB: Hmm, hmm

DF: The pilot revved up the engines, as soon as they were at their peak I took over the four throttles

CB: The throttles? Right

DF: And he took, because that was a, took hold of the steering

CB: Hmm, hmm

DF: And he looked after that, I looked after the engines and the programme to push up there, the throttles, and if we was up we weren’t going to get off on time, I would put it through the gate up to the, which I didn’t like doing because it didn’t do any good to your engines

CB: Right, okay

DF: But occasionally

CB: So, this is an important point really because here you are going along needing to get airborne, how soon did you take the throttles after you started rolling?

DF: Just as soon as it started rolling

CB: You did

DF: Yeah

CB: Right, and so you would advance them slowly?

DF: I’d advance them, and advancing the starboard, that little bit

CB: Starboard outer?

DF: Yes, the starboard

CB: To avoid swing?

DF: To avoid a swing

CB: Hmm

DF: And keep it going like that

CB: And then all of them would be level?

DF: That’s right

CB: So, could you take off without going through the gate?

DF: Occasionally, yes if

CB: If you were fully loaded?

DF: Yes, if we weren’t going too far

CB: Hmm

DF: You know

CB: Oh right, so lighter fuel load? Okay. So, when you say going through the gate, what does that actually mean? In terms of, to the engines?

DF: It meant it was going through, up to a different level of speed, the engines were going up, the

CB: So is this

DF: Screaming, screaming at you

CB: Is this purely throttle or have you got a super charger coming in?

DF: Super, it was a super charger coming in

CB: Hmm

DF: Yeah, but I didn’t like doing that

CB: No. So, in practical terms you can get off with that, how soon would you return to ordinary engine power?

DF: When we were off the ground, the next thing we’d be together round the garage shop

CB: Right

DF: And, as soon as that was up then we’d pull our engines back, just too sufficient to keep travelling up to a certain height at the speed which the navigator wanted us to be

CB: Right

DF: You know

CB: So, you take off, you’re out of the gate, what are you doing about engine synchronisation, how are you dealing with that?

DF: Yes, that, that was one of the things that caused a lot of problems, you couldn’t get them synchronised, it took sometimes a little bit of working on them, one and the other to get them, but once you got them synchronised

CB: How do you do synchronising?

DF: Just by listening to the engines, just

CB: And you were adjusting the pitch?

DF: Yeah, a little bit but just touching your throttle now and again, just watching them, yeah, you were level or the noise was acceptable

CB: Hmm,

[unknown coughing]

CB: Because in practical terms, synchronising is avoiding vibration

DF: Yeah, yeah, that’s right

CB: Hmm

DF: But, it could, it was done correct, but going well

CB: You talked about erm, the mid upper gunner in one situation, so what was that? Could you just describe the event and what happened?

DF: Yes, the mid upper gunner, that’s when we lost him, that was, that was a trip to Berlin, I think we were probably half an hour away from the big city itself

CB: On the way there?

DF: And, on the way there, yes

CB: Right

DF: And, we were hit by flak

CB: Hmm, hmm

DF: We lost the starboard inner engine, it went on fire, and we lost all the communication in the aircraft itself, and the, nobody could hear anything at all, and that, so as I said before, I used to take on the job of watching the gunners, because you was looking out the side window and that, you could see the turrets swinging

CB: Yep

DF: Backward and forward, and this day his wasn’t, it was just steady and not moving, so after sorting out the engine problems and that, cutting off the engine, I decided as I said, to go back and have a look and see if he was alright, I thought he’d just hadn’t any communication and he was just wondering what to do, you know, and was sitting in the turret waiting for things to happen, so, as I say when we got back I tapped the wireless operator and he came back with us, and we met him just going out the back door you know, his hand was still just on that, opening the door, which I managed to, well, the way we done it was, I hit him over the arms, was the oxygen bottle I think, otherwise I think he would have beat us you know, and then we got him back onto the bed and that was it

CB: What was his composure or lack of it, what did it look like?

DF: [sighs] A man that was determined to get out, that’s what it appeared to be, and I think what happened, he must have thought that, he had seen the engine on fire, he’d heard nothing throughout the aircraft itself, I think he thought that the orders had been given to abandon the aircraft, but because he probably thought he was the only one that was cut off from the, not hearing, and he was going to make himself out, but he forgot to take his parachute

CB: Hmm, so you and the wireless operator grabbed him, what did you then do?

DF: We, we bought him back to the middle of the aircraft

CB: To the couch?

DF: To the couch

CB: Hmm

DF: And put him there and if I remember right, we put a strap round him just to keep him on the couch and that, and of course we, it had to be reported when we came down, and that was

CB: Right, so when you got down, what did you do first then?

DF: First down, we, we asked for an ambulance and that took him to the

CB: Sick quarters

DF: Sick quarters

CB: Hmm, hmm

DF: And, as I say we didn’t see him after that

CB: Right

DF: We just reported it. The, the, one thing, he’d been taken to hospital and that was the end then

CB: What was the reaction of the rest of the crew, including the pilot?

DF: Not very good, we didn’t think it was necessary, we thought he should be back maybe after two days or something like that, but then we were told that he wouldn’t be back and we weren’t very happy about it but there’s nothing much you can, you can do

CB: No

DF: He’d done twenty-one ops, so I think he was, there couldn’t be much wrong with him if he’d done twenty-one, it wasn’t as if he’d only done one, you know, but there we are that’s how it goes [pause]

CB: And er, to what extent did you as a crew, know what happened to people who were classified LMF?

DF: We didn’t know at all, and I don’t think, somehow, I don’t think we wanted to know

CB: No

DF: To be honest. We, I don’t think we took in what we saw in the morning when we went in for breakfast, when all the empty tables

CB: Empty seat

DF: Empty seats, I don’t think we really took in that was another, well it was two crews, three crews, four crews probably, but for ages that would two men, later two people like yourselves, you know, I don’t think we took that in, probably didn’t want to take it in

CB: No. So, it was a topic that was discussed later or not?

DF: It was one that was never discussed

CB: Right

DF: No, and even when we landed at Wickenby after that, the only two people that knew, a few of us alone was myself and the pilot, we didn’t tell the rest of the crew, but no we never discussed that at all

CB: The [pause] remaining ten ops, you had other people come in, was it ten different people, was it

DF: No, it

CB: Only a small number and how did they integrate?

DF: They integrated very well, there was one came in for four or five, he was just finishing his tour, and then another one, I think on the same situation and I think about two to finish off the tour between them, and it got

CB: How would people like that be on their own?

DF: Probably they were sick the night the aircraft went out and the aircraft was lost

CB: Ah

DF: With a different gunner on or whatever he was, yeah

CB: Right

DF: And that’s why we wouldn’t fly, leaving one of our, without our whole crew

CB: Yeah

DF: Or giving a crew member to another crew

CB: Right

DF: We’d rather all go and that, that was the same situation, but we didn’t get that, so good

CB: But erm, in terms of background knowledge of what happened to LMF people, what did you understand was their fate?

DF: [pause] Something I’ve never thought very much about, but I knew they were taken off operations, I didn’t know what happened to them after that, I probably didn’t want to know [pause]

CB: Okay. Thank you very much

[interview paused]

CB: So, we talked about a huge range of things and one of the points is that you mentioned is that as soon as operations finished, the crew was dispersed, so during war time you didn’t actually meet up at all, but after the war and with the formation of the 101 association, what links did you have with former members of the crew?