Interview with Bill Spence

Title

Interview with Bill Spence

Description

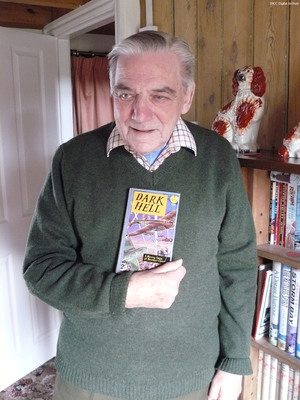

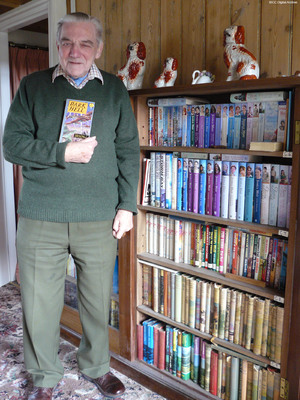

Bill Spence was born in Middlesborough. He abandoned his teacher training and joined the Royal Air Force in 1942, becoming a bomb aimer. He completed 36 operations during his time in Bomber Command. Bill tells of his experiences while training in Canada, how he hoped that he would be posted near the Canadian Rockies and reminisces about the people he met. He tells of being taken off a pilot training course because of an incident with a Tiger Moth, where he ground looped it and it ended up on its nose. He flew in Ansons and Wellingtons, and was then posted to 29 Operational Training Unit; then, in 1944, to a Heavy Conversion Unit at RAF Swinderby. He eventually went to 5 Lancaster Finishing School at RAF Syerston, where he flew on his first Lancaster. Bill was transferred to 44 Squadron based at RAF Dunholme Lodge. He tells of his operation to Harburg, which was their intended target, but they ended up over Hamburg, in the middle of a bombing operation, because wind had not been accounted for. Bill also recounts how his aircraft was one of the first to drop their bombs on Dresden; he contends that the city was a legitimate target and distrusts the judgement of those who did not take part to the operation. After the war, he spent time in Rhodesia and Pretoria, where he tells of his encounter with an Afrikaaner who threatened him because of his ethnicity. After the war, Bill worked at Ampleforth College controlling stores for the catering side. After writing a war novel which was published in a local newspaper, he then tried his hand at writing westerns with Hales Publishing. His pen name was Jim Bowden, after the place he was stationed in Canada. He also writes under the pen name of Jessica Blair and is now on his 26th book.

Creator

Date

2016-03-15

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:58:58 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

ASpenceWD160315, PSpenceWD1601, PSpenceWD1603, PSpenceWD1604,

Transcription

AM: Ok. So today is Tuesday the 15th of March 2016 and this is Annie Moody for the International Bomber Command Centre and today, I’m in Ampleforth with Bill Spence. And Bill’s daughter is also here so if an extra voice appears on the recording, that’s who it is. So thanks for taking part Bill, that’s really good of you, and to start with, can you, can I just have a little bit of background about, about you? So date of birth, where you were born, what your parents did, that sort of thing.

WS: Yes, I was born in 1923 in Middlesbrough. My father was a teacher there, he had originated in Ampleforth, where I’m living now, so my education took place there, and the war broke out. And I was seventeen and about to go to teacher training college down in London, and that was still going through, and I went to the training college at Strawberry Hill, Twickenham and everything was going through fine but we had, the course was only going to be two years.

AM: Right. Can I just ask what made you go to Twickenham if you were from Middlesbrough?

WS: Well I applied to go on a teacher training course and I can’t really remember how it came to be Twickenham except that, in all probability, it was maybe done through the parish in Middlesbrough, because it was a Roman Catholic teaching college.

AM: Right.

WS: So I went there, and the course, which should have been three years, if not four, was clipped to two years in order to fit in with our military training.

AM: Ok.

WS: Right. Well then, I did the first year, started on the second year, when we were told that we would only be able to complete it if we did military training of some kind or another, whilst we were still at college for our last year. So the college started an Army Corps and Air Force training and we could have a pick which we wanted to do [laughs], so I picked to do aircrew training, knowing nothing whatever about it. And so we started to do what would have been the ITW course, which was the first course for aircrew if you went straight into the Air Force and we did that course alongside our teacher training.

AM: Right. Who were the, who were the teachers who did it then? Did you do it at the college or did you go somewhere else to do it?

WS: No, we did it at the college but the course had been drafted in through the RAF and so we got RAF personnel.

AM: Right.

WS: Coming over and giving us lectures on various aspects of the, that particular course and at the end of our, end of our term at the training college, we had to sit an RAF, RAF exam along with our teacher training exams. Now if we passed the RAF training that we’d done there, we’d obviously done the ITW course that we would have done if we’d gone straight in to the RAF. So I did, I did pass it, so that when I went home on leave from college, within, what would it be? Maybe a month certainly, certainly no more than a month, I got the papers to report to RAF in London on such and such a date, so I went down there and then I was shuffled around by the RAF until very soon afterwards, I was on my way to Canada for aircrew training.

AM: Right.

WS: Right.

AM: So tell me about Canada then. How did you get there, first of all, because what year would we be now? Nineteen forty —

WS: Well I was at the teacher training college from ‘40 to ’42.

AM: Right.

WS: So it would be July ‘42 I would think.

AM: Right.

WS: When I actually went into the RAF proper.

AM: Can I just ask you something before we go onto that? So in, in ‘40, ‘41, ’42, you’re in London, doing your training.

WS: Yes.

AM: What was that like as a civilian while the war was going on around you?

WS: Oh, the bombing. Oh, the bombing. Well the first, our first contact with that was the fact that when we went to Strawberry Hill College, part of it had been hit by German bombs and so that part of the college was not in use, and so we were all a bit more crowded together and actually made a lot of bunk beds. They were in the basement of the college for us to sleep in and of course, being in London, you were aware of the bombing going on in other parts of London, but I don’t know, we just coped with it.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Got on with it. This was life as it was then.

AM: Never got a near miss or anything?

WS: No, not really.

AM: Because you’re out, you’re about twelve miles outside —

WS: Yeah.

AM: The centre of London.

WS: Yeah. Yes.

AM: In Twickenham.

WS: Yes. But I mean, we were aware of the destruction there because we used to go in to London, and go to the London Palladium and this, that and the other, and so you were aware of it, yes.

AM: Yeah.

WS: You saw evidence of the bombing.

AM: Right. So the training. You’ve gone back down to London.

WS: Yeah.

AM: And I think you said they shuffled you around a bit.

WS: Yeah. Yes. From there we went to Brighton for a short stay of about, certainly no more than a month, and then we were paraded and said the postings are as follows, and we were shuffled off to Heaton Park in Manchester.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Which was a very big Air Force depot and there were a number of sites, so that we went on to one particular site, but the interesting thing about it was that, I mean, I don’t know how many Air Force people would be there, but it would be a lot, because there were so many different sites, but we all ate in one place, which was on a slight hill in the middle of Heaton Park and ate some of the best food I had in the RAF.

AM: Really.

WS: Yeah, and there was no waiting, it was all sort of organised. Ok, there was a queue to get your food, but you went in a queue and it was divided like that. Some went that way, some went that way and got the plates and food was put on it and off you went, and as I say it was some of the best food I had in the RAF. Well, then I got messed about a bit because they paraded one day and my name was called out. One or two others, who I didn’t know, and you see I’d gone to, I’d gone with the lads that were at training college with me, who had passed like I had done. And my name was called out and I had to report to somewhere in Shropshire, I’ve forgotten the name now, and went down there and feeling pretty miserable because I’d lost all my pals. And then one day, my name was called out again and they said, ‘Get yourself back to Heaton Park.’ So [laughs] I went back to Heaton Park, reported in to whereever I’d been told to report in to, and I was shuffled off to a billet and that was it.

AM: What had you been doing in Shropshire? What did you do while you were there?

WS: Painting stones.

AM: Oh right.

WS: Right.

AM: Because?

WS: Mark the paths out.

AM: Right.

WS: In the dark you see. Crazy. Doing something for, something for us to do, that’s what it really was, because I got the impression they really don’t know what to do with us [laughs]

AM: In between the bits of training.

WS: Yeah. Yeah, that’s right.

AM: ‘Cause up to now its general training that you’ve done.

WS: Yes.

AM: So, except we’d done Air Force training up to ITW standard.

WS: Right. Yes.

AM: We’d passed that of course.

WS: But general. It’s not about your individual training, Navigator, Bomb aimer, whatever, that’s to come.

AM: Not yet. Not yet. That’s to come, that’s to come.

WS: So I was back in Manchester, to Heaton Park, virtually knowing nobody amongst all these people that were there, you see, and then I was enquiring from the corporal that was in charge of our little lot, ‘What’s going to happen to us? What am I going to do? Where am I going?’ and he hadn’t an answer. And then an officer paraded us one day and there was, there would be about twenty of us, and he went through, but he had a list of long personnel, and when he finished there was about twenty of us not on the list. I could have walked out of Heaton Park then and nobody would have known where I was.

AM: But you didn’t.

WS: I didn’t. I pestered them then.

AM: So they just lost a little cohort from the records.

WS: Yeah. Virtually. Virtually. Yes. There, I shouldn’t be saying this should I? But then I went for, I think it was lunch one day, and as I said, I had to go to this centre place, and when I got up there, here’s all me pals from Shropshire come up. I said, ‘Hey, what are you lot doing here?’, ‘Oh, we’re posted overseas, on aircrew training’. I said, ‘What?’ So I then, I went then and made a real nuisance of myself until they said, ‘Righto, we’ll put you back on that course’, so I got back on the course with them. And within, what would it be? Certainly within a fortnight, we were heading up to the Clyde and a ship.

AM: So up to Scotland.

WS: Ye, up to Scotland, on to board ship.

AM: What was the ship like?

WS: It was —

AM: Big one. Little one. How many of you?

WS: Oh [laughs] I don’t know how many there were, but it was crowded because there were, there were postings to various parts. Well, we were all going to Moncton in Canada, before we were diverted off elsewhere but there were, there were some civilians on board that were going back to America, and it was on the RMS Andes, which had just been built as a, well, I presume it would be a cruise ship, but it was a holiday vessel but it never got on to that. We had bunks in the, somewhere or other, one of the halls or somewhere. Of course, we were given various jobs to do and I was lucky again, because I’d palled up with a lad by this time and we got, we got allocated to sweep out the hospital on the ship, and of course, there was nobody in it. [laughs] So until we heard, and then we saw him, that when we were still anchored in the Clyde, this chappie, one night, had been walking around the ship and he’d gone straight out of a door - psst.

AM: In to the water.

WS: Fortunately he was spotted and they pulled him out but they put him into the hospital, on board the ship and he was the only [laughs], he was the only occupation that was there when we were sweeping up. So we swept up and then we, my pal and I were finished. We spent all that voyage sat on the deck huddled together because it was January.

AM: Cold.

WS: And he and I huddled each other to keep each other warm, because if we went down below decks, you just felt sick.

AM: So it’s January. It’s cold and rough seas and everything.

WS: Yes. Yeah. Yeah. It was rough as well. January, yes, it was cold. And as I say we used to sit, every morning we got up, swept up, came out on deck and then, ‘It’s your turn to go to the canteen. Get some tins of pears and biscuits’. And that’s what we lived on for, we couldn’t, we could not stick going down to have a proper meal, so sickly, there we are. Still it was a good voyage. Rough, but —

AM: How long was it?

WS: Hmmn?

AM: How long was it? How long did it take?

WS: I think it took us ten days.

AM: Right.

WS: I think it was ten days, because it was so rough for one thing. In fact, we lost a couple of life boats and we lost because they turned the ships into armed as well, and so we lost a couple of guns as well. It was so rough, but we made it. So we were then taken to a depot at Moncton in New Brunswick, awaiting posting, and I kept my fingers crossed because I wanted to go as far West in Canada as possible, and they started to make the postings to various training places across Canada, and they started in the East with the surname, beginning with A. And they worked through the alphabet so that I was watching, I’m going further West, further West being Spence, and I finished up in Alberta, within sight of the Rockies. Just what I wanted.

AM: Is that why you wanted to be West?

WS: Yeah.

AM: For the Rockies and the scenery and all the rest of it.

WS: Yeah. Yes. I think it was a five days journey on the train then, and then I finished up, then being posted to a little place called Bowden, about eighty miles north of Calgary and did me, because I was training to be a pilot, you see, but I crashed a Tiger Moth, so they took me off the pilot’s course.

AM: When you say you were training to be a pilot.

WS: Yeah.

AM: At what point did they decide that they wanted you to be a pilot, in the beginning? In the first place. Was that while you were still in England or when you got to Canada?

WS: I suppose they, I can’t honestly remember, but I suppose that they’d assessed me on my earlier training, when I was at college with the ITW course, and probably they were wanting pilots as well. I don’t know.

AM: So you came, you came out top of, top of the cream because everybody wanted to be a pilot.

WS: Oh yeah. Yeah. We did. We did you see, I mean, we all imagined ourselves flying Spitfires.

AM: Yeah. Biggles.

WS: But in actual fact, I mean, it’s ok but being wise after the event and being lucky enough to have survived, in actual fact, I always look back and think that that was my best stroke of luck, was being taken off the pilot’s course and sent to be a bomb aimer because if I’m going to be a bomb aimer, apart from one or two training posts, where you would be an instructor, I was more likely to finish up on a bomber squadron. And as I found out, that was the only life worth living in —

AM: Right.

WS: In the RAF.

AM: Ok.

WS: To be on a squadron. On a squadron.

AM: Right. On the pilot thing though, you said you’d in a, I’ve forgotten what you said now, a Gypsy Moth.

WS: Tiger Moth.

AM: Tiger Moth, I beg your pardon.

WS: Yeah.

AM: So what happened in the Tiger Moth then?

WS: Well I don’t think I were, I don’t think I was all that good as a pilot, but no, I mean I flew solo and did a few acrobatics on my own and so on and so forth, and I did a cross country flight on my own. Had to fly the eighty miles down to Calgary, land there and get turned around and fly back, and so on and so forth. Yeah, I got, got on quite well but I landed one day and made a blooming mistake and ground looped and the Tiger Moth finished up on its nose and I suppose that, coupled with maybe I didn’t have the zip to be a pilot. But it didn’t bother me actually.

AM: Did it not? You weren’t bothered when they said —

WS: No. No, I wasn’t bothered and all. I knew then that I was going to be posted to be a bomb aimer.

AM: Right. How did they decide you were going to be a bomb aimer? Do you know? Or is —

WS: No.

AM: No.

WS: No idea, because there were one or two other lads that were taken off the pilot’s course, but then we got split up, so I don’t really know what happened to them.

AM: Right.

WS: So from Bowden, I was sent to a holding unit, if I remember this rightly, in Edmonton. We were paraded, quite a few of us who had come from various places, and we paraded one day and they said, ‘You’re all going to be issued with passes for three weeks leave [laughs], and you’ve got to get out of here by tomorrow night’. So all these documents were given to us, and that was it. We were thrown on our own resolve, you see [laughs], and I’d palled up with a chappie called Cyril Taylor. I said, ‘What are we going to do, Cyril?’ He said, ‘Well. Three weeks’. He said, ‘Whilst we’ve been at Bowden’, ‘cause he was off the course like me, he said, ‘While we’ve been at Bowden’, he said, ‘I got friendly with a farming family near Innisfail’, which was just down the road from where we were. He said, ‘We’ll, we’ll head back there and we can do a bit of a job on the farm for them, you see.’ Got three weeks to fill in, may as well, but I said, ‘Look, first I’d like to go and see the Rockies close at hand’. So he said, ‘Righto. We’ll hitch-hike to Vancouver’. [laughs] So we set off hitch-hiking and we got to Banff and we thought, oh this is quite a nice place, we’ll stay a few days here, you see. Of course there were always places for like, what do they call them? I’ve forgotten the name of them. Where you could get a bed for the night and so on. YMCA’s.

AM: Yes.

WS: And things like this.

AM: Were you in uniform as well?

WS: Oh yes. Yes.

AM: Right. So —

WS: So we stayed in Banff two or three nights, maybe a bit longer, about four nights because we then explored around about Banff and so on, and then we said, ‘Right. If we’re going to Vancouver, we’d better get going again.’ So we were hitch hiking, and we went outside of Banff, on the Vancouver highway, after breakfast one morning, and by the time it was lunchtime, we’d had nothing stopping for us and we were just outside of Banff, on the main road to where we were going, to Vancouver as we thought. But a pickup truck did stop once and he said, ‘Where are you two lads wanting to be?’ And we said, ‘We’re trying to get to Vancouver’. He said, ‘You won’t get’, he said, ‘You won’t get to Vancouver. There’s been a landslide up in the mountains and the road’s all blocked. You won’t get through’, so we went back into Banff to get some lunch. And I can see it now. We’d had our lunch, we’d come out, the main street was down there. There was a side street coming to join it and we were stood on that corner, deciding what we were going to do and we had decided that we would hitch back to Calgary and go to this farm I mentioned, where my pal had been working. We were stood on that corner and the next thing I remember was he was digging me in the elbow. He said, ‘Back here in half an hour’, and ‘To Calgary’, and I was aware that there was a car had pulled up, and it had to pull up for a car going down the main road, and the lady in the car had turned down the window and said to her husband, who was driving, she said, ‘These two lads look as though they want to be going somewhere’, and she said, ‘Where are you two wanting to go?’ And me pal said, ‘Calgary’. That’s when he dug me, because she said to him, ‘Back here in half an hour and we’ll take you’. Right. So we were back in half an hour, no doubt, we got in the car and off we set to go to Calgary, you see. Well, inevitably, on the way you get, ‘Where are you from? Where are you from?’ [laughs] So when Mr Atkinson said to me. ‘Where are you from?’ I said, ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘You won’t know it’, I said, ‘A little place called Ampleforth, in the middle of Yorkshire’. And he sort of, he was driving but he half turned, and he said, ‘I was born in Thirsk’. Right. You made that —

AM: Small world.

WS: And apparently he’d emigrated earlier in his life and had got settled there, and when we met him, he was actually on leave, he was a major in the Canadian Army, and they lived on the outskirts of Calgary and they had a small, small range farm up in the foothills of the Rockies. So on the way back, Mrs Atkinson turned to us and she said, ‘We have two beds made up for any servicemen that we pick up’, she said, ‘You can come, you can stay one night, you can stay two nights, you can stay the rest of your leave’, which was a fortnight. We stayed the fortnight, didn’t we? [laughs] Yeah. So, then, ok, our leave was over. We had to report back to Edmonton, Edmonton sent us to Lethbridge, where we started our bomb aimers training.

AM: Right.

WS: And we finished at Lethbridge, I forget how long that was, then we were sent back to Edmonton, and then we were posted.

AM: Right.

WS: Back to England.

AM: So what was the bomb aimer’s training? How did they train you to be a bomb aimer?

WS: Drop bombs.

AM: So you’re up. You’re flying.

WS: We’re flying.

AM: You say drop bombs.

WS: Yeah. Yeah.

AM: But targeted areas. You’re not dropping bombs are you?

WS: Oh yeah. Yeah. They had set areas. There was far more than one airfield training bomb aimers, but we were, as I say, near Edmonton, which I was quite pleased, because it meant we’d gone further north, so that we were flying over desolate country, but it was quite interesting. And apart from training to drop bombs, we were trained as air gunners.

AM: Right.

WS: Because as a bomb aimer, you were going to man one of the turrets and you had to do a bit of navigation in case the navigator got —

AM: Right. What were you training in? What planes were you training in?

WS: It was Avro, Avro [pause]

AM: Manchester.

WS: No. No. No.

AM: No.

WS: Smaller than that.

AM: Smaller.

WS: Two, two engines.

AM: No.

WS: I’ll look it up for you in a minute.

AM: It’ll come.

WS: I’ll look it up now if you want it on there.

AM: Oh.

[Recording paused]

WS: An Anson. Yes, that’s right.

AM: The Avro Hanson. The Avro Hanson.

WS: No. A N S O N.

AM: Anson, sorry.

WS: Anson.

AM: Anson.

WS: It was, it was a really good plane, a very nice safety plane, good visibility.

AM: Were you training with people who would later become your crew, or was this before crewing up?

WS: No. No. No. No. Nothing to do with the crew. They were training for —

AM: Ok. So this was just bomb aimer’s training.

WS: This was bomb aimer’s training.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Yes, and I mean, there would be navigators training somewhere else.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And so on.

AM: Yeah.

WS: I don’t think any gunners were trained abroad.

AM: No.

WS: I think they were all trained over here, but I’m not sure on that.

AM: What were you actually dropping? Things like smoke bombs?

WS: Yeah.

AM: With the dye in and stuff like that.

WS: Yeah.

AM: So you could see whether you’d —

WS: Or smoke.

AM: How close you got to your target.

WS: Yeah. Yeah. That’s right. Yes. And it was, we’d all be measured because you’d be dropping them on a range. And you see, even when you got to squadron stage, you still did practice bombing and from Lincolnshire, we were down at Wainfleet, Wainfleet was our target there. And there again, they were sort of small smoke bombs. So yeah. So then, where am I? I’ve gone to Lethbridge, gone to, gone back to Edmonton, have I? [pause]. Yeah. I went, I finished my training then in Edmonton, I think that was mostly navigation. I think we maybe did drop a few bombs there but most of the bombs were dropped when we were at Lethbridge. And then we all passed out, and got our wings but, no. No. No. No. No. No. [laughs] I got my wings, there’s your passes, back to Moncton, ready to go back to England. You’ve got, I think we had about four, five days to get to Moncton and a few of us worked it out that we would have time to go to the Niagara Falls, so we did that. That were great. We went on the Maid of the [unclear] and you were right close to the waterfall. Yes. I mean you can still do it, but there’s a but. You see I was a sergeant, having passed out the course.

AM: Right.

WS: And we had, as I say, we had to get back to Moncton. Got to Moncton, found my bunk, and the next day, I was called out and they said, ‘Why are you in that billet?’ I said, ‘Because I want to sleep there’, you see. They said, ‘Didn’t they tell you at Edmonton that you’d been given a commission?’ I said, ‘No. Nobody breathed a word about it’. I said, ‘Look.’ I said, I’ve got sergeant’s stripes on’, ‘Well get yourself off to’, oh what do they call it? Anyway, the offices and tell them and book in there. So I went in to the office and came out ready to put my rings up. Yeah, I got a commission at the end of the course. Came back and —

AM: Was that usual?

WS: No.

AH: What people won’t realise these days, nowadays, is that while dad was in Canada in this day, day and age of communications, his mother died.

AM: Right.

AH: And it was three weeks before he knew that she’d died. In three weeks, she’d been dead and buried before he even knew about it. And nowadays, with mobile phones and communications, I think people don’t realise that. The time it took to get anything anywhere.

AM: And how far away you are.

AH: You are. Yes.

AM: As a young man.

AH: Yes. Yes.

WS: Yes. I mean there was no hope of getting back, even if you could have organised a flight. You know?

AM: So you just found out by letter or —?

WS: Yes.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It was a letter from my dad. That’s right.

AM: What a shock.

WS: That’s right. But what I should also have said, that when I was sent on to the bomb aimer’s course, there were only probably five or six of us going on to that particular course, because when we got there, it was a Australian course. A lot of Australians came in, so I was put into a course with the Australians and I think, I’ve always thought, that the Australians that were there when I joined them, were probably the Australians that were coming from Australia when we were told to get out of our billets for three weeks. I don’t know, I might be wrong, but it seems feasible to me. Yeah. They were a good lot, were the Aussies, you know. I got along with them very well. Particularly one called Jackie Tong who, fortunately, survived. I’ll tell you a bit more about that afterwards [laughs]. So, yeah, so I finished up with the Australian course and when they went to a different depot in Canada to be shipped to England, as we did, we were going to Moncton, and then we were going to the ship at Halifax, and when I got on to the ship at Halifax, there’s these Australians on board, so met up again. Then later on, I’ll finish that off, later on, when I was on a squadron outside of Lincoln, myself and the crew went in to Lincoln one day, and we went to get something to eat at the ABC Cinema Café. And as it happened, we got into a table in the window, and there we were quietly having our tea, when suddenly, I just leapt out of my chair and shouted, ‘There’s Jackie Tong’. And I’d seen one of these Australians who I’d got very, very friendly with, walking up the main street in Lincoln and I just shot off and down the stairs because I didn’t know where he was. I didn’t know anything about him or what had happened to him, and I caught him up, fortunately up the main street. And he was stationed at Waddington, just outside Lincoln, and I was at Dunholme Lodge on the other side of Lincoln. So we met up again, and then after the war, I thought, I wonder what happened to Jackie Tong? I saw him once or twice in Lincoln but after that, after that we were moved from Dunholme, down to Spilsby. And after the war, I thought, I’ll write to Australia House in London, so I did and asked them and almost straight away, they sent me back details. Said that Jackie Tong, so and so, and lived at so and so in Australia, and he’d survived the war and I got in touch with him again.

AM: Right.

WS: And we remained in touch, yes. So where was I, in the middle — [laughs]

AM: Right. Let’s wheel back again then.

AH: You’d finished your training and you were coming back to England.

AM: So you’ve finished your, you’ve finished your training, you’re coming back.

WS: Coming back. Yes. Now, we came back into the Clyde and then we, as officers, were shipped down to Harrogate, just up the road.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So we were to get our uniforms at [pause], I’ve forgotten the name of the tailors now, it was in Harrogate. We were told to go there so I went there and got my uniform and so on, and then got on the bus and came home on leave. Walked out of the, walked out on [laughs], Joan was working down at the college at the time.

AM: Had you met Joan by this point?

WS: Oh yes. Yeah. Yeah. We met when we were still seventeen.

AM: So you, you’d met Joan.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Before ever you went to Canada.

WS: Oh yes. Yes. Yes. So I walked down to the college, knowing where she was working and, of course, she [unclear] when she saw me.

AM: ‘Cause there’s no texting to say, ‘Joan. I’m on my way.’

AH: No.

WS: No, so that was it. There I’m back in England, trained as a bomb aimer and then after that leave, I was then posted,. I had one or two postings actually. I went, went back to Harrogate and then I went to Sidmouth, to join a course at Sidmouth, and it was a sort of officer’s training course but it was chiefly survival.

AM: Right.

WS: And from there —

AM: Can I just ask, survival as in, if you got shot down, if you ditched.

WS: Well, that would help. Yes, I mean, it was just finding your way there, finding your way in the dark and through country and this, that and the other, that sort of thing. Apart from a bit of [pause], I can’t remember what it was now, whatever officer’s needed to know [laughs]

AH: You smoked a pipe, didn’t you? And they gave you a pipe with a little tiny compass in, that we used to love seeing as children.

WS: Which was for escape.

AH: For survival.

WS: Until you knew, you know.

.AM: Yeah. And I can’t remember at this point in the war, whether they had the raft, for if you had to ditch in the sea, and maybe that sort of thing.

WS: We had inflatable. Yeah. Yes. Yes. I think they were in the wings, I can’t remember. Didn’t have to use one fortunately. So I had been at Sidmouth, but I can’t remember if we went back to Harrogate again. No, I don’t think we did. I think I were posted directly from Sidmouth to 5 Group and started my training for a squadron.

AM: So we’re in Lincolnshire now.

WS: We’re in Lincolnshire.

AM: So, I’m just trying to remember. So, at this point, have you actually got a squadron?

WS: No.

AM: No.

WS: No.

AM: So you’ve not crewed up yet and you’ve not got your squadron yet.

WS: No. We went to, we went to OTU, Operational Training Unit.

AM: Yeah. Yeah.

WS: Ah, no. I missed a bit out. I first of all went to Mona. You don’t know where Mona is, do you? It’s on the Isle of Anglesey.

AM: Oh right.

WS: Right. And we went for some more training there, again dropping bombs.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Little bombs, doing navigation. It was prolonging the final course we did in Canada, sort of a refresher course really, and I went there on January the 1st 1944, when we’d done all the other training. And there I was stood —

AM: New Year’s Day.

WS: In the dark, on Bangor Station, not knowing where I was really going, waiting for a train that would take me to Mona. And through the gloom of the night and the day, because it wasn’t a very nice day, I saw a figure down the platform, and I saw he was in officer’s uniform. So I wandered down to him and I said, ‘Excuse me’, I said, ‘Are you going’, ‘cause I saw he was the same rank as me, I said to him, ‘Are you going to Mona?’, ‘Yeah’, he said, ‘Yes I am’. He said, ‘I’m waiting for the train’. I said, ‘Yes. So am I’. We became pals because it so happened, that we finished up on the same squadron.

AM: Right.

WS: In fact, we wangled one posting, the pair of us, so that’s how I met, met him. So I was there on January the 1st, and I was there until February the, well just after the 20th. February 20th would be our last flight from Mona. And then I went to, on March the 16th, I did my first flight in a Wellington. We’re moving up now, and I was there until April, well, April the 12th was my last flight from Bitteswell.

AM: Right.

WS: And I then flew from Bruntingthorpe, 29 OTU which was the same as, it was a substation of Bitteswell. There was some more training to do, and I was there until May the, May the 11th

AM: It just always seems such a long drawn out time.

AH: Yes. I’m thinking, when he’s saying these dates, I’m thinking, the war’s going to be over before he gets there [laughs]

AM: Well yeah.

WS: Right. So then I went, did my first flight, I can’t tell you exactly when I went. June the 25th 1944, I was sent to Heavy Conversion Unit at Swinderby.

AM: Right.

WS: That’s when we went on to four engine bombers.

AM: Right. So in the meanwhile, we’ve had D-day, and everything’s happened.

WS: Yeah. Yeah. I’m going to slip back in a minute or two.

AM: Ok.

WS: And I was there until July the 17th, when I did my last flight from Swinderby, and from Swinderby, I went to 5 Lancaster Finishing School at Syerston. I did my first flight from there on August the 10th. That was the first time I flew in a Lancaster.

AM: Did you like it? What was the Lancaster like then after the others? A big boy.

WS: Well to begin with, I did not like the Stirling, which I’d been on. It was too big, too cumbersome. Apart from something else that happened. So we were going, the pilot, I said how I joined up with my aircrew, haven’t I yet?

AM: Right. No, no, you haven’t told me about crewing up. When —

WS: I’ll tell you about that in a minute.

AM: Right. Ok.

WS: I’ll just finish this bit.

AM: Alright.

WS: Because we’re talking about the Lancaster. This pilot told us that he was going to fly the Lancaster on a training flight, because he hadn’t flown a Lancaster before. On a training flight, he said, ‘If you want to come, you can come, if you don’t, it doesn’t matter, because it’s just for me’. The pilot. ‘It’s just for me to get used to flying a Lancaster’. I said, ‘Oh no’, I said, ‘I’m going to come’. See [laughs], I found out that the mid-upper gunner wasn’t going to go. He’d already done a tour of operations and he knew the Lancaster, so I said, ‘Right. I’m going to fly in the mid-upper turret and get a nice good view’, you see. So I get up there, and off we go. We’re flying along and the instructor’s telling Mike what to do, etcetera, etcetera, you see and then, suddenly, he says, I might not get these in the right order, but he said, ‘Switch off the starboard outer’. Mike said, ‘There you are’. Flying on three engines, go on a bit further. ‘Switch off the port outer’, switched that off, there you are. Two engines. I, I’m sat up in the mid-upper gunner, seeing these propellers stopping.

AM: Can you hear the instructions? You’re on the intercom?

WS: Oh yes. Yeah. Because I’m on the intercom.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And then he told Mike to switch off one of the other engines. So I thought, where’s my parachute? I might need this, you see. Well, it flew like a bird on one engine and I thought, oh, this is the aeroplane for me, I’m glad I’m on one. Great. Great. So that was my first flight in a Lancaster, and I was there from August the 10th until August the 14th, so I was only there four days. And then posted to a squadron.

AM: Right. Wheel, just wheel back to crewing up then. How did that happen?

WS: Crewing up. Well that happened at, that happened at OUT, Operational Training Unit, which I was at Bitteswell, I think, yeah, I was at Bitteswell. [pause] And from arriving there, and I can’t tell you exactly when I arrived there, but February the 20th, I was at [pause], I was at [pause], I was at Mona. No, we’d moved from Mona. No, we hadn’t [pages turning]. Yeah. I went to Bitteswell and we paraded one day, and there was a mass of men. We were told, ‘Those are all aircrew. Go and get yourself crewed up’. It was just a stroke of luck, and I don’t know how long I, I didn’t get crewed up that day, I know that. It might have been two or three days afterwards, I was in my billet, and it was a Nissen hut with rows of beds on either side [pause], and I thought, really and truly, I’d better be getting crewed up. Because I’d asked one pilot, an Australian, and he said, ‘I’m sorry. I’ve got an air bomber’, so I tried a New Zealander, and he said ‘I’m sorry. I’ve got a bomb aimer’, you see. So I was sat in my, I was sat on my bed thinking who do I, who am I going to ask for next, you see, and then this six foot four fellow walked in, and as he walked past the bottom of my bed I said, ‘Hey’, I said, ‘Excuse me. Have you got a bomb aimer yet?’ And, of course, he was a pilot, you see, I could see that. ‘Have you got a bomb aimer yet?’ He said, ‘No’, he said. So I said, ‘Well, what about you and I crewing up then?’ He said, ‘Well, let me have a look at your logbook’, so he had a look at my logbook, see what I’d done, and he said, ‘Yeah. Righto’. So that’s how I got, that’s how I got a pilot. ‘So I said have you got any, any other crew?’ He said, ‘Oh yeah’, he said. I don’t know whether it was there and then, but if it wasn’t there and then, it was the next day and he introduced me to two gunners and the navigator and a wireless operator. He’d got his crew except for me, I think. Is that right? Yeah, I think it was.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So I’d got a crew then, you see, and they were a great set.

AM: I counted.

WS: Unfortunately,

AM: Oh we’re missing the flight engineer as well.

WS: Yeah, we didn’t get him yet.

AM: Oh right. I thought I’d only got to six.

WS: Yes. They were, they were a good lot but we, whether this was the cause or not, I have no idea, but we landed one night in the Wellington, we’d been on a night cross country and we landed. I was sat up next to Mike, and I was looking out of that window, and Mike was there, and I thought to myself, I thought, those landing lights are going by rather quickly. And just at that point, Mike shouted out, he said, ‘The brake’s aren’t working’. So I thought, I hope he doesn’t try to turn at the end of the runway, because if he turned at the other road, he’d have gone over, you see. However, he didn’t, he went straight on, off the end of the runway, bounced across the field, through a hedge, banked across another field, finished up in a ditch, nose first. So we, we were scrambling to get out and the navigator was putting his maps back into his bag. I said, ‘Hey’, I said, ‘Get out. Quick’, he said, ‘Mike’s had a heavy landing tonight’. I said, ‘We’ve crashed. Get out’, out he goes, the rear gunner had turned his turret and tumbled out the back, you see.

AM: Right. Yeah.

WS: That’s the way they had to get out. And he was stood outside our plane, I was saying, ‘You silly buggers. Get out. Get out. It’ll be on fire. There’s petrol all over the place. Get out’. Fortunately, it didn’t go on fire, but the control on the aerodrome, didn’t know that we’d crashed. Don’t put that in.

AM: [unclear] these are the interesting bits.

WS: And, of course, as soon as they knew, they whipped the ambulance out for us and ferried us back in, and we had to go and see the MO, and he checked us over. Nobody was hurt, but the aircraft was a complete write off.

AM: Yeah.

WS: It broke its back, so that was our adventure on OTU. I was sorry about the Wellington, it was a nice aircraft. So, where have we got to now?

AM: Right, so we’ve crewed up. We’ve not got our flight engineer yet.

WS: Ah right. Yes, well —

AM: And we’ve not got our squadron yet.

WS: Yes. We got our flight engineer, I think it was the next, let me see. I don’t know whether I’ll have it down here. Yeah, there we are. We got him at Swinderby.

AM: Right.

WS: Which was the next one, after that previous one. We got him on June the 25th. He was from, and we also got a new air gunner. Now why did we get a new air gunner? Because our rear gunner decided he did not want to be aircrew anymore. Now, don’t ask me why, because I never knew. Whether, a little bit of a rumour went around, that his girlfriend had used pressure on him, but I don’t know whether that was right or not, or whether the fact that we’d crashed made him change his mind.

AM: Spooked him. Had he, was he a new one or had he already done a tour?

WS: No. No. He was a new one.

AM: He was new.

WS: Yeah, he was a new one.

AM: So he hadn’t actually been up there in anger yet.

WS: No. No, he hadn’t.

AM: In an operation.

WS: No. No. You see, I don’t know the full story, because you never got to know. You never really got to know.

AM: Were you allowed to just decide that?

WS: You never really got to know. They kept it quiet because they didn’t want it to affect the rest of the crew, which it could have done.

AM: Well, yeah. And was he just allowed to revert to ground crew or —

WS: I don’t know what happened to him.

AM: No.

WS: I’ve no idea what happened to him.

AM: Because sometimes —

WS: He just disappeared.

AM: Right.

WS: He just completely disappeared. Now, as I understood it, I thought they whipped, as I say, the aircrew, if anybody did that [pause] LMF. Lack of moral fibre.

AM: Yeah.

WS: They whipped them out of the way.

AM: Right.

WS: Because they didn’t want them contaminating aircrew.

AM: Yeah.

WS: In the squadron or anything like that, and he just disappeared. And I never, ever heard what happened to him.

AM: Yeah. I wondered about the lack of moral fibre thing, because you’ve done all that training, all the, and then you just decide you don’t want to do it.

WS: Yeah. As I say I’ve no idea. I mean, he showed no sign to us that he wanted, he never mentioned it. I mean he obviously, he must obviously have mentioned it to the pilot, because he was in charge of the crew. He may not have done, of course, he may have gone to the adjutant or he may have gone to some other officer in charge of ground crew, of aircrew, and said he wanted to pack it in, you know. Just have no idea. Never enquired because we got a new air gunner, a warrant, he was a warrant officer, Cole, who had done a tour.

AM: Right.

WS: So that we knew that when he joined us, he would only have to do twenty for a second tour. So he came to the squadron with us, obviously, but when he’d done his twenty, he was finished, and then we flew with just odd bods really.

AM: Yeah.

WS: In the mid-upper turret. Yeah. Where are we?

AM: Right. Squadron. We’ve not got a squadron yet.

WS: Haven’t got a squadron yet. Well, because my pilot was Rhodesian, he was sent to 44 Squadron, which was 44 Rhodesia Squadron, because the Rhodesian government financed the squadron, but they weren’t all Rhodesians, obviously, but he was. He was a Rhodesian and that’s why we finished up on 44 Squadron.

AM: Right. Based at — ?

WS: Well, we were at Dunholme Lodge then.

AM: Dunholme Lodge.

WS: And we were at Dunholme Lodge [pages turning]. Well, we just slip back to, because this is another thing that people won’t realise. Where are we? We were at Swinderby, right, and on the 16th of July [pause], we had finished our course, it was only a short course at Swinderby, because it was really getting the pilot familiarised with the Lancaster. Nevertheless, we had to train as a crew as well, so we finished there on July the 16th, having arrived there on June the 25th, so it was shortish. And as soon as we finished the course, you could go on leave. And we, knowing it was a short course, Mike and I —

AH: The pilot.

WS: Mike and I had sort of palled up a bit with another pilot and a bomb aimer, who were officers, and decided that we knew we weren’t going to be there very long. We couldn’t be bothered to go out, down to Newark or in to Lincoln, night after night sort of thing, so we sat playing cards in one of our billets, and just for a bit of money, pass the time. And so, when we finished the course, we could go on leave. Those two hadn’t finished, so they were still finishing off, but we knew, when we got back, they’d probably be there. So I went on leave then, went back [pause], the two that we’d been playing cards with, had been killed. Been taking off one night, and it was in a Stirling, which I didn’t like.

AM: On operations?

WS: No. No.

AM: No. Because you’re not on a squadron yet, are you?

WS: On training.

AM: On training.

WS: Yeah, and they would have been finishing like we had, you see, but as soon as you’d finished your training, you didn’t really bother. You weren’t on a course really, you could go off on leave. Then we got back and found that they’d both been killed.

AM: And what had happened? Do you know?

WS: The crew, the whole crew had been killed. Now the Stirling was under-powered and they didn’t clear the trees at the end of the runway.

AM: Taking off.

WS: Yeah. You see that’s another aspect people won’t realise.

AM: Well, yeah, because they’re young men, they’ve done all the training, they haven’t even got to a squadron.

WS: So, we joined the squadron on August the 21st. No, sorry, we didn’t. That is when we did our first flight on a squadron, and that was on August the 21st so we would, between [pages turning]. Where are we? Between the August the 14th and August the 21st, I can’t really tell you what we’d been doing, must have had a bit of leave. I know that because, as I say, we came back and found that the other two poor fellas had been killed. But the first flight, was a training flight on August the 21st 1944 from Dunholme Lodge.

AM: Right.

WS: And I was at Dunholme Lodge then, until [pages turning], that’s right, until September the 30th, when we flew from Dunholme Lodge to Spilsby.

AM: To Spilsby.

WS: Yeah.

AM: I’m going to press pause.

WS: Yeah.

[Recording paused]

AM: So, where are we? We’re in 44 Squadron.

WS: Yeah.

AM: And at the moment, we’re at Dunholme Lodge.

WS: Are we —

AM: But we haven’t done our first, you haven’t done your first operation yet.

WS: Right.

AM: So tell me about the first operation. Where to? What did it feel like?

WS: Twenty eight. That occurred. [pause] Eight days.

[pause]

AM: Where was, where was your first operation to?

WS: I was wondering whether Anne was coming back. Our first operation. We joined the squadron, and had our first flight on the squadron on August the 21st 1944, and our first operation was on August the 29th 1944. Now there was a bit of a, oh, I think people still think today that, and I’ve seen it in writing actually, that aircrew were generally sent on a fairly, what they called, easy target for their first op. There was no easy target, you could be shot down if you’d just crossed the channel, as well as going thousands of miles. But our first operation, we were airborne for eleven and three quarter hours.

AM: So, right, right over to Germany then. The other side of Germany.

WS: Yeah. We were going to Konigsberg in East Prussia.

AM: Right.

WS: And we flew out over the North Sea, over to Sweden, and we went over friendly territory. At least not —

AM: Yeah.

WS: It weren’t a war country, and flew south. We were warned that if you went over into Sweden, you would probably get shot at, but they probably wouldn’t be aiming at you. Just warning you to keep away [laughs]. And then we went to Konigsberg, and we had to, as it turned out, we had to fly around and around for about a quarter of an hour, twenty minutes, while they got the target mapped accurately. Did that, we were called in and did the bombing. We came back and we were diverted to Fiskerton because there was fog over.

AM: What was it like? Actually like. How many? Was it a big bomber stream? Because this would be the first time that you’d actually been in a full stream of aircraft.

WS: Yeah, but you see, it was night. It was at night, so we didn’t really.

AM: So you couldn’t really see. You couldn’t see.

WS: No. You might occasionally, if you got a bit near, see just a faint outline of a Lancaster, but otherwise you weren’t, and it was a bit strange, because we did go on, well, we went on one or two daylight raids, but we went on a daylight raid later on. It was to bomb the Germans in Boulogne, and to see all those Lancasters and other aircraft flying down south over England, you just thought. And at night, they would be there as well and you can’t see them. Made you aware of the danger that there was.

AM: Oh absolutely.

WS: In the dark.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And yet the darkness was a cover for you. But there we are.

AM: That first operation. Can you remember, were you scared? Were you exhilarated? Did you —

WS: I always say, that when people say, weren’t you frightened or were you afraid or whatever, I say, yes you were, but you didn’t show it, you kept it in. And I’ve always reckoned, it was the only way to survive really. But yes, you had to be aware of it, otherwise, if you weren’t aware of the danger from other aircraft that were flying nearby, or you didn’t keep a look out for German fighters or whatever, then you probably wouldn’t survive. But I think it all stemmed from being afraid. But as I say you didn’t, you were young, you didn’t bother with it.

AM: Yeah.

WS: I don’t know whether that answers your question.

AM: No. It just interests me the different ways that people felt about it.

AH: Yeah.

AM: Some people really excited to go. Some people definitely were not.

WS: Yeah. I also think, as well, that you knew if you were flying with a good crew, you knew that they were all on top of their job, you knew that they would always be alert and so on, and if a gunner fell asleep, or anything like that, he’s not alert, is he? And he’s endangering your life. So if you have trust in your crew, you were more likely to survive.

AM: And different ones have said, in the bomber streams the, your trust was actually in the navigator.

WS: Oh yes. Yes. Yes.

AM: To keep you safe.

WS: Yes. Yeah.

AM: And away from everything else, and on track for where you were going.

WS: Yes. You were, you had certain courses to fly and he directed you onto there. You see, your gunners, where you expected them to be awake, and keep their eye out.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And identify enemy aircraft, or even your own aircraft, and warn you that you might be crashing, so.

AH: What I think I never realised. You talk about the bomb aimer, the pilot, the gunners but you’re down there in the front.

AM: Yeah.

AH: And if you see something, you’re telling the navigator. You’re looking out for the navigator.

AM: Yeah.

AH: You’ve got a gun as well.

AM: Yeah.

AH: If needs be. So everybody’s helping everybody else, aren’t they? It’s not just bomb aimer.

WS: No.

AM: You’re the eyes at the front, the bomb aimer.

WS: Oh yes. If necessary, you would fire the guns in defence and if the, if the navigator got hurt, you would go back and help him, and this, that and the other.

AM: On all the operations that you did, did they, the gunners, ever actually fire the guns?

WS: I can’t remember them actually firing the guns, but on the other hand, I’ve spoken to our rear gunner about this, and he’s quoted one particular time when our radar equipment, which was a big bulge under, under the fuselage of the Lancaster, we came back and when I got out, I saw it was all gone. It had obviously, I automatically thought that it had been anti-aircraft fire, but the, our rear gunner said, ‘No. It wasn’t. It was a fighter attack’. Now I can’t remember the fighter attack, but, but I have no doubt that he was right, because there were fighters that particular night. You knew there were more fighters around.

AM: Yeah. Yeah.

WS: You see Konigsberg, if you read the accounts of Konigsberg raid, you’ll find, I think it’s on that one, that there were a lot of fighters around, but I can’t remember them. I don’t think we saw one.

AM: Because you were concentrating on what you were doing.

WS: Well. Yes. Partially and also, partially, the fighter could have been a few miles away.

AM: And actually dropping your bombs, that very first time. So it’s been marked, the Pathfinders have been out, you’ve got your target, you know where it’s going. Did you hit the target? ‘Cause then all the photographs are taken of, of —

WS: Yes. I hope so. I mean, of course, you’re crew would look out as well and see, but there again, you’ve got to be careful, because they wouldn’t want to divide their attention between keeping a look out for fighters coming in, say. But, yes, you could be aware of your bombs, depending on your target, and what sort of visibility was, and whether the aircraft was sort of, going to break away after the attack. You may not see it, but there was, the best example I can give you of that, was that we went, it was one of the canal raids we went on, the Mittenval Canal or the other one. Dortmund Dams canal or —

AM: Dortmund Dams. Yeah.

WS: Yeah. One of those raids we went on, two or three, attacking the canals. Now, when we got to the target area, just before we got to it actually, the master bomber was assessing the aiming point, and there was some confusion arose, because I will swear, to this day, and so would Mike, the pilot, and so would some of the other crew, that we were told to come down to five thousand feet to bomb. From, I think, probably about twelve or fifteen thousand, which was quite a way away down.

AM: That’s quite low. Yeah.

WS: On the other hand, there were reports came in that that, that that was altered to back to the normal level, but we never heard that, and a lot of other crew didn’t either. But Mike said, ‘Right we’re going down’, five thousand feet. Well by the time we got down to five thousand feet, we were below the markers, that the marker force were dropping, so we were lit up like daylight, you see. Well you could see the canal as plain as anything, and Mike said, ‘Right, we’re going in’. So I will swear to this day, that I got a very good sighting on the canal, but on that occasion, I was able to see the bombs actually fall and they did, they fell right alongside the canal bank. So that probably, I can’t swear to this, but probably, from where they fell I would have thought that it breached the canal side.

AM: Breached. Yeah.

WS: And therefore, the water, which we were trying to get rid of, the water we were trying to get of, would have all flooded out. I don’t know. There you are.

AM: I just have this picture of, you, the markers and then the ones that were still at twelve thousand feet, dropping bombs.

WS: Yeah.

AH: And the danger was the other bombs hitting you.

WS: Yeah, I mean, ok, we went in and did the bombing and I thought afterwards, sometime afterwards, I thought, well, every time we go out on a bombing raid, it would be like that. Not that you were dropping below a certain height. No. No.

AM: But you’re all at different heights.

WS: But you are at different heights, yes, but not as marked, as that was because we, the master bomber had assessed it, that if we come down to a lower level, which was a big drop, seven thousand feet or thereabouts, that we would have a better chance of hitting the target. I don’t know.

AM: Did any of your crew get DFM’s or DFC’s or — ?

WS: No.

AM: No.

WS: No.

AM: You weren’t fool hardy enough to get in those situations. What was the story about Hamburg that your daughter was talking about?

WS: She shouldn’t have told you that one.

AM: Go on.

WS: Well we were, we were attacking, we weren’t attacking Hamburg actually, we were attacking Harburg, which was on the other side of the river, the other side of the estuary. And it was a lovely night, and it was dark and flying along, no sign of anything happening, and then, suddenly, there was anti-aircraft fire absolutely pounding around us. Mike immediately took evasive action, which was [unclear], you see, and I’m down in the front with him going up and down, like this. The gunners were wondering what was happening, and so on and so forth, you see, and I suddenly realised we’d overshot the target, and we hadn’t seen any markers, so unfortunately, the navigator got us to the target area too soon. I think there had been a following wind, which he hadn’t calculated for, and we just, we just kept on flying like that, and eventually, of course, we passed, and then we realised that the amount of aircraft fire that was coming up, we’d flown over Hamburg which, of course, was a big target. How on earth we didn’t get shot down, I do not know, but we suddenly, the anti-aircraft fire lessened and lessened, and so we must have passed over, passed right over Hamburg. Passed.

AM: Did you manage to drop your bombs?

WS: Well then, we flew around to the proper target.

AM: Right.

WS: Which was Harburg, not Hamburg. Yeah. And we dropped our bombs and then came home.

AM: Right.

WS: So. Right, we got home. When you get home, you’re out the aircraft, we go to the mess for our bacon and egg.

AM: Yeah. Bacon and egg. Everybody remembers their bacon and egg.

WS: When we got back, we went in to the mess, and there were crews sat there, but one particular crew, he was a Rhodesian, like Mike was, and they’d trained together. The bomb aimer and I had trained together, so we were sort of very pally together, you see. Mike and I sat down, then one of them said, ‘Did you see that silly bugger that was over Hamburg?’ And we, Mike and I, looked at each other, and just said, ‘Yeah it was us’. ‘Well you daft buggers, what were you over there for?’ But I just couldn’t believe that we hadn’t —

AM: That you escaped it.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Got out in one piece.

WS: The damage that you would have thought that we would have. I mean we —

AM: What was the flak damage to it? To the plane?

WS: Well no, there was a few holes, but it wasn’t.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Nothing drastic or anything like that.

AM: You could bodge them up.

WS: No. Talking about that, you go back to our first raid over Konigsberg, which I’ve already mentioned. As we came away from the target, I always had to check in the bomb bay by opening a little door.

AM: Yeah.

WS: To see if the bombs had all gone. Well on that occasion, I opened the little hatch, the bombs had gone, but I saw drip, drip, drip and it was red. And, you see, I was on an eye level with the pilot’s feet and the engineer’s feet, so those two bodies were there and I thought, has somebody been hit? ‘Cause we’d had quite a lot of firing up there. And I ran my hand on the, because I was on, my eye level, I had to go a step up into the fuselage, my eye was on a level with that, so I saw this quite clearly dripping through, and I put my hand on it, and I thought, it’s a bit red is this, so I said, I called them up on the, and I said, ‘Is everybody alright up there?’ And Mike said, ‘Yes. Yeah. What’s the matter?’ I said. ‘Well, there’s some dripping, coming through out of the bomb bay’. Anyway, to cut a long story short, it was our hydraulics had got hit. Now, we did not really know whether we would get the undercarriage down.

AM: All the way home.

WS: All the way home.

AM: First operation.

WS: First operation.

AM: I thought you were going to say it was blood.

WS: No, it wasn’t as it happened you see, because it was the same colour, but there we are, and what we didn’t know, whether we would get the undercarriage down, and we thought we’d got it down, but we weren’t, didn’t know whether it was locked or not, ‘cause when they come down, they was locked, you see. We had no indication on the dash board in front of the pilot that it was locked down. And then we found we were going to have to land in fog at Fiskerton.

AM: So, was that the one that you were diverted to Fiskerton?

WS: Yeah.

AM: Yeah.

WS: But everything was alright, as it happened.

AM: But you got down ok.

WS: We got down ok.

AM: And lived to tell the tale.

WS: Lived to tell the tale. But there you are, you see.

AM: Did you ever have to land in the fog? You know, that they had all the flares.

WS: Yeah. Yeah.

AM: I can’t remember what they were called, all the fire things along the runway.

WS: The Fido.

AM: That’s it.

WS: Fido.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Yeah. Yes. It’s a very strange sensation that, because you were, you were sort of, lighting fog, and you were going down and down, and you thought we were going to go straight into the ground, you see. You were still in fog. You could see the glows, but they weren’t doing anything really. You could see flames coming up, and then you’d come out of that fog, complete clearance. And by that time the pilot was landing.

AM: You were down.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So the pilot had to be on the ball really. He didn’t want to fly into the deck. Had to know what he was doing.

AM: How many operations did you do?

WS: Thirty six.

AM: Thirty.

WS: Thirty six.

AM: Thirty six. And was that a full operation? That was, no, that was more than a full operation.

WS: No. Thirty. Thirty was a full operation.

AM: Thirty was the full op.

WS: Yeah.

AM: ‘Cause the numbers changed a bit towards the end of the war, didn’t they, but that, so thirty was still a full operation. A full tour.

WS: Thirty was a full tour and also the pilot did what we called a dickie run. He went with another crew just for the experience of a first raid.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So Mike had done that, and including that, in that total, a tour was thirty but during our tour, I certainly spent, through 5 Group, that they suddenly put it up to thirty six, so we had six more to do. I tell you what, you could tell that there was bit of demoralisation, because more aircraft got shot down than generally.

AM: On the final six.

WS: Yeah. So I don’t know.

AM: Where else did you go? Were they mainly over Germany? The ones that you did? Any other interesting stories? I’m sure there are. About some of these operations.

WS: Bremerhaven, Monchengladbach.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Munster, Karlsruhe. That Monchengladbach one, I think that was the one, the 19th of September, we can check it up of course, was the raid that Guy Gibson got the chop on.

AM: Oh right.

WS: He got shot down over Holland on the way back, but I can, I can hear him now telling us, ‘Home chaps. Good prang’. And so on, words to that effect. Bremen, Brunswick, Bergen. Oh, we had to land away there. Dusseldorf, Gravenhorst. No, that wasn’t the one. Harburg, there we are, the one I’ve just been telling you about

AM: Yeah.

WS: Where we flew [laughs], when we flew over Hamburg. That was on the 11th of November and that then, yeah, then the next one was on the 21st, 10 days later. That was the one that I told you about, us having to drop below five thousand feet to bomb, down in here, bombed from four thousand. Did a few mining operations.

AM: And this says on the ground moving up through Europe after D-day.

AH: Yeah.

WS: Yeah. Yes.

AM: Yeah.

WS: There was one, I can’t remember which one when we were supporting the advancing troops. Did quite a lot of oil targets, and our last trip was a daylight trip on April the 4th 1945 to a place called Nordhausen, yeah.

AM: What was? I was going to say, what was the difference between the daylight ones and the night ones apart from the obvious, It was daylight.

WS: You could see things.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Yeah, I don’t know. You couldn’t see at night but there we are. You might, you’d more easily crash, I suppose, at night.

AM: Did it feel more dangerous? The fact that you could see more things, but of course, more people could see you as well.

WS: Yeah.

AM: If there were any fighters around.

WS: I don’t know we just had to take it as another raid and get on with it. And I’m going to say unconsciously, that’s the wrong word, consciously you would —

AM: Yeah.

WS: Adapt to the change night and day.

AM: To what, way it was. And you were with the whole crew for the whole thirty six.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Ops.

WS: That was good.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Well when I’m saying yes, the same crew. No, because our mid-upper gunner only had to do twenty.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Yeah. Mid upper gunners were sort of odd bods. We got one that we had five or six times. I did go to Dresden if you — Dresden.

AM: You did?

WS: Yeah. In fact, we were one of the first aircraft to drop bombs on Dresden on that raid.

AM: And you did it because you were told to and —

WS: Yeah. And not —

AM: People have said different things about Dresden

WS: Yeah. Well they’re all wrong.

AM: Yeah. Oh, all sorts of different. Absolutely. All sorts of different things.

WS: Yes.

AM: But as young men.

WS: What was, what was a pity is, that these people who wrote about Dresden, the majority of them had not been there. They’d not been on the raid. And apart from that, they knew little about what, and they jumped to the conclusion that, because it had nice buildings and so on that it shouldn’t have been attacked. They don’t look at the fact that it was still producing war weapons.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And I think the reason for that is because it wasn’t heavy industry, but who was making all the instruments and so on? You never hear that mentioned by some of them. And the majority of people that criticise Dresden, I think you will find are only surmising on facts from the war, in the way they want to interpret them. To me, it was a genuine target and, but we were actually told that they had this light industry. We were also told that it was a big railway centre and that we were bombing it to help the Russians. Disrupting transport. And I think if you look in to the facts, Churchill instigated the raid along with, I mean he was the Commander in Chief. It’s alright talking about Harris, but Harris was obeying orders from above, wasn’t he?

AM: Oh yeah.

WS: I’ve forgotten what I was going to say now. [laughs] The only thing I criticise Churchill about, you know. I think he was the right man at the right time, but he let the bomber boys down at the end of the war.

AH: He was a politician.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Yeah. Politics, wasn’t it?

WS: Yes. Yeah.

AH: It was all politics after the war.

WS: I mean, ok, they’ll quote that he did say, I don’t know the exact quotation, but he sort of praised the bomber. He said, ‘The bombers will win the war’. That was early on in the war.

AM: Yeah.

WS: But he never said we had done at the end of the war.

AM: That you’d actually done it. Yeah.

WS: But, I say, that even that attitude was wrong because you needed, you needed the bombers, you needed the fighters, you needed the soldiers, you need the Navy. The lot.

AM: The whole allied, the whole allied effort.

WS: To win a war.

AM: To actually do it.

Yeah. You can’t single out any one of us that won the war. Nobody did.

AM: I suppose what you think is what would have happened if you’d taken one of the groups away.

WS: Yes.

AM: If you’d have had no bombers.

WS: Yes.

AM: But yeah. It was an allied effort, wasn’t it? By name.

WS: Yeah.

AM: And that was what it was.

WS: There we are.

AM: Did you, on your last operation did you actually know that was your last one, then?

WS: Yes.

AM: ‘Cause that was your thirty sixth.

WS: Yes. Yes. Yes.

AM: And pretty much, you’re not going to go on another tour after that, are you. Where are we now? April ’45.

WS: Yeah. They asked us if we’d like to go to the Middle East. Not Middle East, the Far East.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And I think Mike was all for it actually. The rest of us said no. We’d managed to come through alright. We were not going to risk going out there.

AM: So what did you do? What happened then, after the last operation?

WS: Well I came on leave [laughs]

AM: And you were married by now. You got, you were married part of the way through the war, weren’t you?

WS: Yeah. I’d only done about five aircraft operations.

AM: When you, when you married.

WS: So I knew I had about another twenty five to do, you see.

AM: Yeah.

WS: But we, Joan and I decided that we would, we would get married, but it would be at the end of the war. We hadn’t really sort of gone into it to that extent but we, I think, without saying a lot about it we had, in a way, decided we would wait till the end of the war. Right. So I come on leave when I’d done about five operations and we went for a day in York, and Joan said to me, she said, ‘Will you come and see Geraldine Kelly with me?’ Now Geraldine Kelly was at the convent with Joan in York and she said Geraldine had got married shortly before that. Her husband was a Canadian and they were flying out of one of the aerodromes around York and he’d been shot down and she didn’t know what had happened to him. And so I said, ‘Yeah. I’ll come and see her’. So, we went to see her. Joan knew which offices she was in, in Coney Street, so I went to see her and had a chat and so on and so forth, and she still hadn’t heard anything about her husband. And we were coming away and Geraldine said, ‘When are you two getting married?’ And we said, ‘Well, we’re probably going to wait until after the war’. And Geraldine said, ‘Don’t’. She said, ‘Don’t wait. I had seven days with John. They were the happiest of my life’. So we came home and got married.

AM: Of course, you didn’t, didn’t know how long the war was going to last at that point.

WS: No. So we came home, we decided that yes, we would get married. We put it all in operation and so it was my next leave was going to be that when we got married. Well, of course, you never knew when your next leave was because you were on a roster. So if somebody ahead of you got killed, you moved up the roster. And then one day, Mike came away from, probably the adjutant’s office and he came over. Fortunately our aircraft was parked near the offices and we always used to gather there, and Mike came over one day and said, ‘You can go on leave tomorrow’. I got to the phone, rang Joan up said, ‘I’m coming home tomorrow. Can we marry on Friday?’ But she had everything in place for a wedding to take place, you see, so she said, ‘Yeah, righto’. [laughs] So I told the crew, ‘You’re coming to a wedding on Friday’, so they, they arranged to come. They were going to stay in York overnight.

AM: Right.

WS: And then come out by Reliance bus to the wedding in the college church, and so that’s it.

AM: So you did.

WS: We got married. And to go back to Geraldine, she heard that he had survived.

AM: He had survived.

WS: He had bailed out and he, I think, I think he must have been taken prisoner of war but it was only a short war, of course. And so they were married and they settled in Canada ‘cause he was Canadian and I think she had six children.

AM: Right. On the, when you’d actually finished your operations, then you came home on leave.

WS: Yeah.

AM: But then, then what happened? How long before demob, because people went all sorts of strange places.

AH: Africa.

AM: You went to Africa.

WS: Well first of all when I went back after the leave, I was then sent to Winthorpe as an instructor.

AM: Right.

WS: To crews going through the process. There is a funny little story, yes, I was instructor at Winthorpe. Then of course, the war finished and they don’t want to be training bomb aimers, would they? And I then got sent on to an equipment officer course at [pause] Bicester. Just outside of Oxford, Bicester, yes.

AM: Bicester.

WS: Yes, just outside Oxford. So I did the officer’s training course and then I was posted to Stafford, where there was a very big, and had been there most of the war, if not all the war, maintenance unit which had several sites. And I was sent to one of those sites as second to the officer in charge of that particular site, but I knew that the next overseas posting that came through to the maintenance unit, I would be on the bike, because they were all ground, ground crew wallahs who had been nicely cosy through the war and didn’t want disturbing, sort of thing, you see. So that was it. Posting didn’t come through, posting didn’t come through, you see. And then was called to the adjutant’s office. ‘Posting’s in for you. You’re going to Cairo’. So I said, ‘I’m sorry, I’m not going to Cairo’, ‘Why not?’ I said, ‘Because you can’t send me there’. He said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Why not?’ I said, ‘Because I am under the medical officer’, and I said, ‘You can’t post me as long as I’m under the medical officer’. ‘What’s the matter?’ I said, ‘I’m waiting for an eye test’. Two days later, no three days later, I was at an optician. Right. So the next day I’m called into the adjutant’s office and he said, ‘You’ve had your eye test’, he said, ‘You’re going to Cairo’. I said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘You’ve already filled the post’, he said, ‘Yes I have’, he said, ‘But I can get it switched’, and he said, ‘But’, he said, ‘I have to have your permission’. So, I said, ‘No’, I said, ‘I’m not going to Cairo’, I said. He said, ‘Well the next posting that comes in, you will have to go’. I said, ‘I’ll take my luck. I’ll take a chance where it is’. He said, ‘You might be going to somewhere like Singapore out in the Far East’, so I said it didn’t matter, I’d take my chance. The posting came through the next day and it was to Rhodesia. So, so the adjutant said, ‘You’re going to Rhodesia’. He said, ‘You can switch, if you like, with one of the others’. I said, ‘I’m not switching if I’m going to Rhodesia’. ‘Cause my pilot was a Rhodesian.

AM: Well yeah.

WS: He’d been demobbed and gone home you see, for one thing. I said I’d rather go to Rhodesia, so he couldn’t do anything about it. He had to send me to Rhodesia.

AM: And what did you actually do in Rhodesia?

WS: Well I —

AH: He had to get there first.

WS: I had to get to Rhodesia.

AM: Well, ok. How did you get to Rhodesia then?

WS: By ship.

AM: For how long?

WS: You couldn’t fly.

AM: No.

WS: You couldn’t fly, you see, there was no flying. That isn’t strictly true actually but I couldn’t have gone.

AM: Yeah.

WS: On a flight. They were only very official flights, so I had to go by ship. So I came home on leave.

AM: I’m just trying to think of the journey then.

AH: Yeah.

WS: Oh yes. Yeah. Because you had to go through the Med.

AM: Yeah.

WS: Down the Suez Canal.

AM: Yeah.

WS: And you see calling at various places on the way and we did have quite a number of South African troops going home on board as well, so it was really a troop ship in a way, but there were quite a number of civilians on board. And we just jogged along really, I don’t know how long it took us, took us quite a while because we stopped here and there and everywhere. And then having got to Durban where there was an RAF Headquarters they said well we, ‘You are going to Rhodesia, so you will have to get the train from here up to Rhodesia,’ which I think in those days was five days, I think.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So, right, fair enough, off we go. There were four of us, five, four, four I think. One of them, when we got, when we got to Rhodesia, we had to report in to the headquarters in Salisbury. I was a senior officer so he started with the others. He had postings for them. One went to Gwelo, somewhere in Rhodesia, so that was one out the way. Another one went to one of them, in the Middle East. That left two and he hadn’t any postings through for them, and then he sent for me and he said, ‘Will you volunteer to stay on in the Air Force?’ I said, ‘Why are you asking me that?’ He said, ‘Well, it’s ridiculous. They’ve sent you all the way from England’, he said, ‘You’ve only got a month to do before you’re demobbed’. He said, ‘It’ll take you a month to learn the job that you’ve been sent to do’, he said, ‘You would be coming here to be responsible for all the equipment that is coming in to Rhodesia, because we’re going to resurrect the Empire Air Training Scheme again, you see’, because it had been like the one that went to Canada.

AM: Yeah.

WS: So I said, ‘No, I don’t want to volunteer’, so, ‘You’ll be getting promotion almost immediately’. He said, ‘You’d be up to squadron leader very soon.’

AM: So you’re a flight lieutenant at this point.

WS: Yeah.

AM: Yeah