Interview with Frank Simpson

Title

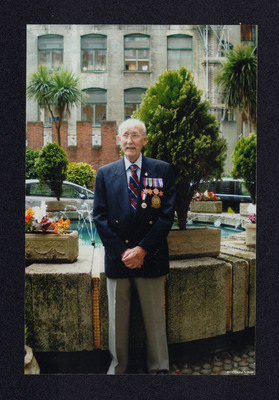

Interview with Frank Simpson

Description

Frank Simpson was born in Manchester and volunteered to be an air gunner after joining the RAF. He flew in ‘Ollie’s Bus’ which was named after the Canadian pilot. He describes seeing the German aircraft with the Schrage Musik, the upward firing guns and seeing aircraft shot down. His own pilot had to take evasive action when they were caught in searchlights over Berlin. He also recalls gunnery duty beside the airfield to protect the incoming aircraft from German intruder aircraft.

Creator

Date

2017-03-02

Language

Type

Format

00:37:28 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

ASimpsonF170203, PSimpsonF1702, PSimpsonF1704

Transcription

SP: This is Suzanne Pescott. I’m interviewing Frank Simpson today for the International Bomber Command Centre’s Digital Archive. We’re at Frank’s home and it’s the 3rd of February 2017. Thank you Frank for agreeing to talk to me today. Also present at the interview is Dave Simpson, Frank’s son. And Frank’s daughter Cath. Ok. So, Frank first of all then do you want to talk about what made you join the RAF. What was life like before?

FS: Well, when the war kicked off all the young fellas I think, well ninety percent of them, who would join up somewhere and I went — oh you wasn’t with me. It was my dad that was with me then. I’m forgetting. Went to Manchester and there was a place there where you could volunteer. RAF you know and what have you. And I said I ‘d like to join the RAF and he says, ‘How old are you?’ I said, ‘I’m fifteen.’ He said, ‘You can come back when you’re sixteen.’ So that’s what I did but at that time army, navy and air force all had [pause] like Scouts and I joined the RAF one, you know and other fellas joined the navy ones. And other fellas joined the army ones. And they all had bits of uniforms and also on some of them, especially on the one I was in they had bombs — not bombs [pause] trumpets. And drums. So, I played a drum when I was in the, you know, before that. Yeah. So, I became a drummer and every Sunday I went and we all met in a place. A church wasn’t it? I think. Something like that. And talked about things. You know. And then the following week we’d go back again and they’d ask us questions and the vicar would ask questions and it was a freezing church. And there was three people in the church. Two of them coughing their heads off and it was freezing in the church as well, you know. A bit of a silly thing to say really isn’t it that but, but anyway I eventually got called up. Down to London I think it was. Yeah. Down to London. To the place that — tennis. There was a tennis place in London. And that had been taken over by the RAF. So, we went into there and of course inside a couple of days all the clothes had been taken off and we’d all been given new uniforms and things and then they sent the clothes home to the house where we lived at that time. Still got it upstairs I think. Yeah [laughs] No, but we had a good time there and we were there four or five weeks. Going around London was very very interesting because we’d never been to London before, you know and they started taking us around. And then we went — people with posh houses took us in for tea which was amazing and at that particular time the house we went to was a lovely house. Four or five storeys you know. And we went in and there was what looked to me a little square thing. And I said, ‘What’s that?’ She said, ‘Oh you won’t know anything about it. It’s called a TV.’ You know. An early TV and it wouldn’t turn on because it had started just before the war and then when the war came in they had to turn it all off but I actually saw the little — it was about seven inches square, you know. When you look at this thing now. But it was all enjoyable down there and we did all sorts of things and we met. They all gave us uniforms of course and shoes and I think we had hats. Yes. We had the flat hats, you know. But we did that and then they sent us out to various places during the sort of twelve months of our first try there and it was various schools and restaurants. Not restaurants. Schools mainly. And some of us of course — or some of the fellas, not lads, weren’t particularly interested in schools when they went to school. So they just went there and when they were fourteen they left but I was quite interested in schools and I used to make things as you know. I even had a little telly — camera when I was ten years of age. Taking pictures with a camera at that age. But it was a good thing. We went around to various places and stayed in various people’s houses because there was no room for us. That was over in the other side of the country now, that. But apart from that everything went on and then eventually we were sent to Scotland. To the place where they played golf and we spent six or eight months there, something like that, and learned an awful lot about flying which was a good thing. And when we came back, when we finished there they sent all of us to Heaton Park. Now, I was the only one at Heaton Park who knew where it was. And so, after we’d been there three or four days I went to see one of the officers there and said, ‘What’s happening here?’ You know. He said, ‘Well, we’re waiting for boats to take you to America or Canada or South Africa’ he says but we, you know. And I thought boats to go to places like that. Not for me. ‘What else is there?’ And he said, ‘We’re short of air gunners.’ So, I said, ‘Put my name down as an air gunner.’ And a few days later, it’s a shame really because I was at Heaton Park then and I could come home every night and see my little sweetheart couldn’t I? That’s her up there. And anyway, they sent me to South Wales and I became an air gunner in South Wales after about six or eight weeks. And they sent me then to Heaton Park again I think. And eventually from Heaton Park I was sent out to a squadron I think. Oh. Not a squadron. It wasn’t a squadron but it was to do with aircraft. I was already in the aircraft. Gunners weren’t much. It was the fellas in the aircraft. The pilots and navigators and bomb aimers that were doing the work or the training. We only sat there, you know, waiting in case some Germans come at night time which they did. They’d fly over from the continent because they were only twenty five mile away, you know. But, we had a good time there and eventually we got sent to a place the other side the country which was near the water which you flew over to get to Germany and places like that. And we — it was a terrible place. Do you remember going there with us Dave? I can’t remember what it was called but you took us years after didn’t you? And it was falling to pieces but eventually after that, after a few weeks there they sent us down to the big one in Yorkshire. In [pause] not Yorkshire. God.

SP: At Lincoln? In Lincoln.

FS: Lincoln.

SP: Lincoln

FS: Sent us to Lincoln there. And I thought that’s it. Yeah. So, from there we were very happy. We got up every day or every two or three days and flew over somewhere, you know. Practicing this was because I was ok just sat in there — me and the other gunner but the navigators and the people like that they had to train in the plane. But we had a good time there, you know. Come down to Lincoln and a couple of pounds — a couple of shillings in your pocket you could have a pint of beer which was very handy because I didn’t drink much then anyway. I don’t drink much now. No. But they was good days and then eventually they sent us out to — well we stayed there, where we were and we started flying to Germany from there, you know and coming back of an evening and it was very nice. If you got back in time you could go to the town itself in Lincoln and have a couple of beers. All part of life in those days. But eventually the war came to an end and on that particular day it was the worst thing I’ve ever seen in my life. We flew over Berlin — literally just above the houses and looking through the windows on the floor was hundreds and hundreds of dead people. Little boys, little girls, mothers and fathers all, all over the place. And also, at the same time the Russians were there doing the same thing and the Americans were there doing the same thing and it was about the worst. It’s a thing I can never forget. Seeing all these little babies, little lads, little, even parents bent up, twisted up, bowled over and stood on, you know. Heart-breaking really but it happened and then we turned back and came home. Then we were sent around various places in England because when we got back to England after the war had finished Canadians, Americans, South Africans they were on the boat going home inside a week. So, all the lads from England and that — they were put in tents in farms to sleep there for a few days till they knew what they were going to do with them and where they were going to send you too. But it was, it was ok you know and we used to go to the local villages and the ladies in the local villages would always give us a cake or, you know something like that which were very very good. And then we were sent to various places because they didn’t know what to do with us. And I was sent down to South Wales to be [pause] I can’t remember what it was but it didn’t suit me and they said oh that’s ok Mr, you know, sergeant as they called us. ‘We’ll find somewhere else to send you.’ And they sent us over then to the other side of the country. What’s it called? God I can’t remember now. Right on the coast. A place where you can go on holidays and all that sort of caper. I can’t remember the name but they sent us there and I learned to type, type there because everything there you know, they’d teach you how to type and I used to type anything that they wanted. And eventually I come home on, you know, on a leash as you might say and I was taken back after a week and at one time they shouted us and said that, ‘We’re going to have to ask you to do something.’ Well, sergeant as it was then. So I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘We’ve got a man here we’ve got to take over to a prison.’ So that was good that. Just what you wanted wasn’t it? A fella going, ferrying someone over to prison. Anyway, he was a coloured fella had been over here shortly. One of the lads that had come over later on, you know. Anyway, we took him over to his prison and then came back home and started working at the place I was going — learning how to type. Going around places and measuring up for whether they had space for us. And then I was sent to Blackpool before I came out of the air force altogether and spent quite a few weeks in Blackpool. And living, not here but in Manchester. Salford I should say. We used to go dancing in there and going in to the Blackpool Tower, you know. It was a smashing place to go in to in those days. And having a glass of beer I think because we didn’t have much money. And then after about two or three weeks got called in to a place full of overcoats and trousers and shirts and socks. So they gave us a new pair of trousers and new shirts and all well you know all sorts of brand new stuff. New shoes. New socks. New shirts and a nice black suit. And they said, ‘Well you can go home now when you’re ready Frank.’ I said , ‘Well what time is it?’ He said, ‘It’s half past four.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll leave it ‘til tomorrow.’ Which I did and came home the following day and my little sweetheart was all ready for me then. We didn’t get married then though did we ‘cause we had no money. Yeah. But that’s about it love from the air force point of view. Now, is that any use?

SP: That’s really good, Frank. So –

DS: One thing you didn’t mention was when you did the drops over Holland. The food drops.

FS: Oh that’s right. Yeah. The war was just finishing and we flew over Holland. Just literally over the roofs of the towns. And we took food with us. Well, they supplied food. You know. The air force. And we dropped it to them. Into schoolyards. And then the following day we did the same again but they were all out. All the young kids. They were only about six or seven. All with their big, “Thank you.” “Thank you RAF.” You know. And that was a good thing. And then we moved after that for a while into some farm land and we were dropping food to the farmers then. You know, for the farmers as well as the people themselves and that was another good — good day I think. Something to remember. You know. But the war had finished then and that was about it. Well nothing else apart from coming out of the air force which I did eventually. Came out and they gave us a suit. Well I just told you that didn’t I? A suit and trousers. But then I came home and the day I got home the fire wasn’t in at home because my dad he was working and my mum was — she was [pause] so I had to go around the corner to a coal place and get a coal wagon weighing about two tons, a half a hundred weight in it, and push it over and light the fire, you know. A little bit of happiness but it was, they were good days those, after that. Good days and good nights. But there was four of us in the family and I used to bath on Saturday night. My dad was first, my sister second, somebody else third and I was fourth. All in a little tin bath thing. You know a bath. And it was bloody freezing by the time I got in there you know. Even though it was in front of the fire. But it was good days those and then I eventually found my little sweetheart again and we got married. Ooh a long time after didn’t we? Yeah. A long time after. But she died two years ago unfortunately with cancer. But I’m still here with Alzheimer’s. Have you heard of Alzheimers? Yes. Good. And it doesn’t do anything. I’m quite happy. Happy as a lark. It doesn’t bother me. Alzheimer’s. Wherever I am. So — and apart from that I’ve enjoyed my life. I’ve got a nice little house and don’t drive a car any more. I just have my nice glass of wine with my evening meal, you know. But apart from that we’re getting towards the end I think. Anything else you can think of dear? Not really no. No. You understand that don’t you?

SP: Frank. What did you do after the war? So obviously you came out.

FS: Oh I came out.

SP: What job did you go to after the war?

FS: I was an electrician. And I remember going to a place in Manchester. I did a lot of sockets, you know. Put a lot of sockets in because at that time TV wasn’t coming — it had just started to come out and nobody had a socket on the wall to plug in. so being an electrician I did quite a few of those jobs for people and I think I charged them a half a crown or something like that. Which, a half a crown was a lot of money in those days. And I think I also — I can’t remember what else I did. I did one or two jobs but the electrician was the one I stayed with. And I can’t remember what the others were now. They were jobs that I did for people.

DS: You used to do lots of other electrician jobs for local authorities.

FS: Oh electrical. Yeah. People would come to me and say can you do this and can you do that?

DS: And you used to take me and you would send me under the floor when you were rewiring houses.

FS: That’s right. That’s right. For rewiring. To get the cable.

DS: To get the cable up for it.

FS: That’s when we used to cut the floor didn’t we?

DS: Yeah.

FS: And then drop you under there. Yeah. Oh aye.

DS: [unclear]

FS: I gave you half a crown didn’t I?

DS: I think you might have done. Yeah. And then, and then you went into printing. You became an engraver.

FS: An engraver.

DS: [unclear]

FS: Became an engraver. Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. Yeah. Making the, you made the metal plates didn’t you? And then printed them on to paper. Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. Whatever it was for. Yeah. That was good. That was another good thing that. Yeah.

DS: You stayed doing that. You stayed as an engraver until you retired.

FS: Yeah. I was. That’s right. Yeah. I retired then. Retired. And happy ever since. Yeah. Now, is that enough love?

SP: Thanks for that Frank. Ok Frank. Do you want to tell me about where you were based during the war?

FS: Well the first place was Kelstern is it? That was Kelstern where I were first sent. That was when I was trained. But before I trained I was in Scotland. And I don’t know whether I’ve mentioned this have I? Have I?

DS: St Andrews.

FS: St Andrews. Yeah. I’ve not mentioned this before. Oh, so went up to Scotland. They sent us all over, all over the country. To schools and all sorts of places doing silly, well not silly things but things that was interesting and I can’t remember what they were but we went up to Scotland and we did quite a lot of training up there for flying. And that was at a big Scottish place. I can’t remember the name of it now.

DS: St Andrews.

FS: St Andrews and we was there for five or six — five months I think. Something like that. Training and going out on to the actual golf course and training on there to do things which was necessary you know. But eventually that finished and we came to Heaton Park. Have I mentioned Heaton. I’ve mentioned that so —

DS: And you got crewed up at Heaton Park.

Cath: Yeah.

DS: You met your crew.

FS: That’s right yeah.

SP: Do you want to talk about crewing up at Heaton Park?

FS: Oh of course.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Let me think a little moment. Was it at Heaton Park where I crewed up? [pause] Oh, I think that was Scotland. No.

DS: No. That was Heaton Park.

FS: Heaton Park. Anyway, I went to Heaton Park which was ideal because I lived close by and could get the tram of a morning and get there for 7/8 o’clock I think and did a lot of training in there. How to do this. How to do that. And which was very good. We’d done previously in other places but they always kept up on there. Guns and things, you know. But we stayed there for a while and then have I said anything about going to South Wales? Yes. Oh well that would be it then.

DS: What do you remember about crewing up at Heaton Park when all the gunners were together and all the navs were together and you all became a crew? [pause] Ollie, the skipper, came around and said, ‘We’re looking for gunners,’ and —

FS: Was that Heaton Park? Oh, well that’s possible. Yeah. Heaton Park. That was when I was stationed close at Heaton Park. It was very convenient for me to get home of an evening which they’d let me do you know and get back there for 8 o’clock in the morning which was ideal for my little lady then. But we did pick people up. Literally, put you in a big, a large area with ten aircraft. Not aircraft. Ten people who flew aircraft.

DS: Pilots.

FS: Ten or twelve people who did something else and then the gunners etcetera etcetera. Eight of them. Eight of them altogether. Seven or eight. Yeah. And we picked each other up then and we went over to them and said to the skipper, the pilot and we said, ‘Are you alright for two gunners?’ He said, ‘Certainly.’ And he was a Canadian. A good lad. And he was an old fella. He was thirty, you know. And — but he used to send, or his parents used to send cigarettes and chocolate from Canada. And my old, my dad smoking cigarettes. He’s not here now. Smoked too many cigarettes. And chocolates they’d send over and he’d give them to us you know. So, I’d bring them home and give them to my little sweetheart and we couldn’t be wrong. But that was a good day when we did all that and then we started flying with each other. Sitting in the areas where you were and then they’d take off and you had to do a bit of moving around with, you know, with your guns and that but we didn’t fire but we got used to doing what things were. And that was a good idea too so —

DS: Can you remember the name of the plane?

FS: Ollie’s Bus. Ollie. The pilot was called Ollie something so, we called it Ollie’s bus, you know. And they were all nice, good lads in there. Canadians and there was an American lad in there. And when we went out for a drink, for a beer, of a night-time we didn’t have any money but he went out, you know and sat in a pub but they’d, there was a lot of Yanks where we were down south, they’d just started coming over from America. And the fella we was with was American. He’d leave us and go over to his mates straight away. Which was understandable, you know. But those were good days too moving around England in different aircraft. And when we was in one aircraft, two seater, two engines, I can’t remember what it was now but we were flying in it, doing different things. The gunners trying different guns. Then you would come down and sit down on the floor and as we were sitting down on the floor the pilot said, ‘One of the engines has stopped.’ So, we all had to get down on the floor somewhere and wedge yourself against something while he landed. You know. But he landed ok and it was all part of life in those days. All part of life. Yeah. And well I can’t remember it at the moment. I can’t remember it you know.

SP: About your base at Kelstern — what was that like? Where you were based.

FS: In —

SP: Kelstern in Lincolnshire.

FS: Lincolnshire.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Oh, it was a cracking place that. It was. It was a cracking place. So, we were sent there later on in the war because I think they had space then. And the place that we was in was falling to pieces so they said we’ll send you to Kelstern. And that was — not Kelstern, the one in — what’s the name of the one in York.

DS: Scampton.

FS: Scampton. That’s right. They sent us to Scampton which was the posh one then. So we spent some time at Scampton and went over Germany from Scampton and the other places. You know. Bombed them and that and then the war stopped and things happened then. When I say things happened they didn’t know what to do because all the lads from Canada and America and South Africa they were all going home the following day. So, we were — they didn’t know what to do with us so they sent us to camps which was empty. You know. They’d been full of people at one time and then they were all out then. Empty. So they sent us out of these and we used to go to the various villages then close by. And they used to look after us. Well I say look after us — you’d go in the pub and they’d buy you a pint, you know and things like that and look after us. It was smashing there I think. Those little pubs. Not pubs. Took us to church. I think they took us church — I wasn’t a church goer. And happy life. A happy life and eventually took us somewhere else down south. And I thought why are they sending me down here for because I can’t do what they’re doing here. I’m a man who uses his hands and his brain. And they sent me then over to the other side of the country again and I learned to type. So I was typing things for them and eventually they sent me from there to Blackpool and after Blackpool I was sent home. So that was the end of me as a gunner.

SP: Frank, during the war years were there any particular time when you went up in a Lancaster that you remember? Was there any particular operations that stand out?

FS: I’m trying to think.

DS: I remember you telling me once you got caught in the searchlights over Berlin and you had to corkscrew down.

FS: Aye. That’s right. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right over Berlin. And there’s usually about a few hundred that was going over there from here, you know and this particular night they got the old guns. Not the guns going. They get the lights, headlights. The —

DS: Searchlights.

FS: Searchlights. They’d got the searchlights going and the, God knows, underneath so they were following us all the way and then the German aircraft — they came after us and we had to do a bit of flying like this, you know. And fortunately we got away with it that particular time. And we did two or three over Germany. Well more than that two or three. We did about half a dozen, a dozen or so I think over Germany. And each time we were flying over we’d see somebody in the distance flying underneath an aircraft. And it was dark because it we always went over at night and as we got a bit closer we could see that the plane underneath was a German plane.

DS: A fighter.

FS: And it had guns pointing upwards and all he did was press the button and brrrrrm and kill the plane itself with all the lads on. So, you had to watch out for that which we did. But these things happen in war and not much you could do about it and I was lucky to get back alive. That’s the way I look at it, you know. And very very nice. Very nice I thought, that there was always some hot food ready when you got back. You got back at 5 o’clock in a morning you’d always got a breakfast ready for you. And somebody would shout, ‘Do you like your egg?’ I’d say, ‘No, I don’t want my egg.’ ‘Well, I’ll have it. Pass the plate over, you know. But I’ve never liked eggs. Not eggs. Something I don’t like. I can’t remember now. What is it I don’t like?

Cath: Onions.

FS: Onions. I hate onions so and I still hate onions and I’ll tell them now, so. Those were good days and then there was a lot of moving around. Then I think I’ve told you about this. Moving around. Yeah.

SP: And when you were at Kelstern you said that you had to sometimes sit at the side of the runway with your gun.

FS: Correct.

SP: What was that for?

FS: Well in those days it was always evening when the Germans came over. Like at the same time as went we over there. And the aircraft, there was usually about four aircraft, five aircraft could be six aircraft coming at a time, coming in and we sat on each side with our brrrrrr and there could be, and there had been, after the last aircraft came in a German aircraft would follow them in and shoot at him as he was landing. So, they put two of us, one on each side, to keep our eyes open after the last one came in because they, and we shot at them and I think we missed them, you know. But it stopped. They stopped coming in after that. Which was another part of life isn’t it, you know. But a good life. I’ve had a good life and I’m still here which is the main thing, you know. Anything more you want love?

SP: Is there anything else you can think of you that you’ve not had the chance to say or anything?

FS: I’ll just have a think.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Yeah. Turn it off.

[recording paused]

FS: Ready.

SP: Ok Frank. You were talking about your crew and other crews. Is there anything that stands out about –?

FS: Well there was one member of my crew. The crew I was in. And it was too much for him. Even training was too much for him so he did a runner up to Scotland. I think he was a Scots fellow. I may be wrong. But he’d gone up there possibly because it was easier to find somebody up there. A place to go to wasn’t it? Scotland in those days. But eventually the police found out, the RAF police found him and brought him back and he was brought out on to the space that there was there and all the people in the area itself. When I say the people, all the staff, you know, all the people that worked.

DS: All the crews.

FS: The aircrew. Not aircrew. All the RAF people. They all came out and he was stood there and then his medals were dragged off and he was taken off by two policemen then and sent somewhere else. As a, as a thing, you know. Like — it was like being taken to prison isn’t it? But I can understand it because it was a terrible thing to have in your mind. But I’m not, it was in my mind but nowt you could do about it. Nothing you could do about it, you know but it was good — looking back on it it was a good thing and it’s kept me going and still here at ninety two. So not bad going is it?

SP: No.

FS: No. I know.

SP: Yeah. Frank if I can thank you for your time. I think that’s been great. Thank you very much. And thank you Dave as well for helping out with that. So —

FS: You enjoyed it.

SP: Yes. Very much so. Always a pleasure to hear stories.

FS: Like this. Have you heard other stories like this?

SP: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Every one’s slightly different but —

FS: Oh, they’re all slightly different but they have the same —

SP: Still, great, great stories. Yeah. Yeah.

FS: The same outlook as we all had as you might say. Yeah. We may not come back from this one, you know. Every time you got in the plane you’d think by Jerry am I going to come back. And you’d see somebody. You were flying over with them and all of a sudden you’d see him with a half a wing blown off.

DS: The thing that sticks in my mind —

[recording paused]

FS: Fills it all up doesn’t it for you?

SP: Right. Just a couple of bits to add Frank. You were just chatting then after we’d finished about your nicknames that you had during the war which I thought were really interesting. So, do you want to let us know about that? Your nicknames and why you had those.

FS: Algernon Montague Simpson wasn’t it?

DS: That was the name you gave yourself.

FS: That’s what I gave myself. Yeah.

SP: But that wasn’t your name.

FS: No. Frank. I was Frank. Algernon Montague Simpson. Yeah. That still comes my way. A while ago now. Yeah. Here you are Frank how are you? Tea and coffee and that. Yeah.

SP: So, all your crew knew you as that.

FS: Oh yeah.

SP: Yeah.

FS: They knew I was Frank but I used to call, well they used to say Frank Algernon you know. I don’t know why it came up. These sort of things. But they do in your life don’t they?

SP: Yeah. And then you had a nickname because you were quite slim during the war.

FS: What was it? Yeah. Skinny bugger.

Cath: Satchel arse.

FS: Satchel arse. Yeah. There was no room for me. I used to slip off the, where we were sat with the gunnery. Sat there I used to slip off there. Oooh get back on again. Yeah, I was only a skinny bugger then. I still am really. Oh they were good days those. Good days. Another thing that they had in those days was they had a toilet in the aircraft. And I was sat in the, where I usually sit and saw somebody walking down. And I saw him get on the toilet and do what was necessary and it was the pilot. He couldn’t do anything else but go to the toilet [laughs] No. They were good days those. Good days. Still comes through my mind occasionally. Even more so now. Yeah. Yeah. But that’s, yeah, cracking that. Well I can’t think of anything else now.

SP: That’s great Frank. So, I’ll just thank you again for that. And thank you Dave.

FS: I’m going to charge of course [laughs]

SP: I’ll let them know.

FS: Well, when the war kicked off all the young fellas I think, well ninety percent of them, who would join up somewhere and I went — oh you wasn’t with me. It was my dad that was with me then. I’m forgetting. Went to Manchester and there was a place there where you could volunteer. RAF you know and what have you. And I said I ‘d like to join the RAF and he says, ‘How old are you?’ I said, ‘I’m fifteen.’ He said, ‘You can come back when you’re sixteen.’ So that’s what I did but at that time army, navy and air force all had [pause] like Scouts and I joined the RAF one, you know and other fellas joined the navy ones. And other fellas joined the army ones. And they all had bits of uniforms and also on some of them, especially on the one I was in they had bombs — not bombs [pause] trumpets. And drums. So, I played a drum when I was in the, you know, before that. Yeah. So, I became a drummer and every Sunday I went and we all met in a place. A church wasn’t it? I think. Something like that. And talked about things. You know. And then the following week we’d go back again and they’d ask us questions and the vicar would ask questions and it was a freezing church. And there was three people in the church. Two of them coughing their heads off and it was freezing in the church as well, you know. A bit of a silly thing to say really isn’t it that but, but anyway I eventually got called up. Down to London I think it was. Yeah. Down to London. To the place that — tennis. There was a tennis place in London. And that had been taken over by the RAF. So, we went into there and of course inside a couple of days all the clothes had been taken off and we’d all been given new uniforms and things and then they sent the clothes home to the house where we lived at that time. Still got it upstairs I think. Yeah [laughs] No, but we had a good time there and we were there four or five weeks. Going around London was very very interesting because we’d never been to London before, you know and they started taking us around. And then we went — people with posh houses took us in for tea which was amazing and at that particular time the house we went to was a lovely house. Four or five storeys you know. And we went in and there was what looked to me a little square thing. And I said, ‘What’s that?’ She said, ‘Oh you won’t know anything about it. It’s called a TV.’ You know. An early TV and it wouldn’t turn on because it had started just before the war and then when the war came in they had to turn it all off but I actually saw the little — it was about seven inches square, you know. When you look at this thing now. But it was all enjoyable down there and we did all sorts of things and we met. They all gave us uniforms of course and shoes and I think we had hats. Yes. We had the flat hats, you know. But we did that and then they sent us out to various places during the sort of twelve months of our first try there and it was various schools and restaurants. Not restaurants. Schools mainly. And some of us of course — or some of the fellas, not lads, weren’t particularly interested in schools when they went to school. So they just went there and when they were fourteen they left but I was quite interested in schools and I used to make things as you know. I even had a little telly — camera when I was ten years of age. Taking pictures with a camera at that age. But it was a good thing. We went around to various places and stayed in various people’s houses because there was no room for us. That was over in the other side of the country now, that. But apart from that everything went on and then eventually we were sent to Scotland. To the place where they played golf and we spent six or eight months there, something like that, and learned an awful lot about flying which was a good thing. And when we came back, when we finished there they sent all of us to Heaton Park. Now, I was the only one at Heaton Park who knew where it was. And so, after we’d been there three or four days I went to see one of the officers there and said, ‘What’s happening here?’ You know. He said, ‘Well, we’re waiting for boats to take you to America or Canada or South Africa’ he says but we, you know. And I thought boats to go to places like that. Not for me. ‘What else is there?’ And he said, ‘We’re short of air gunners.’ So, I said, ‘Put my name down as an air gunner.’ And a few days later, it’s a shame really because I was at Heaton Park then and I could come home every night and see my little sweetheart couldn’t I? That’s her up there. And anyway, they sent me to South Wales and I became an air gunner in South Wales after about six or eight weeks. And they sent me then to Heaton Park again I think. And eventually from Heaton Park I was sent out to a squadron I think. Oh. Not a squadron. It wasn’t a squadron but it was to do with aircraft. I was already in the aircraft. Gunners weren’t much. It was the fellas in the aircraft. The pilots and navigators and bomb aimers that were doing the work or the training. We only sat there, you know, waiting in case some Germans come at night time which they did. They’d fly over from the continent because they were only twenty five mile away, you know. But, we had a good time there and eventually we got sent to a place the other side the country which was near the water which you flew over to get to Germany and places like that. And we — it was a terrible place. Do you remember going there with us Dave? I can’t remember what it was called but you took us years after didn’t you? And it was falling to pieces but eventually after that, after a few weeks there they sent us down to the big one in Yorkshire. In [pause] not Yorkshire. God.

SP: At Lincoln? In Lincoln.

FS: Lincoln.

SP: Lincoln

FS: Sent us to Lincoln there. And I thought that’s it. Yeah. So, from there we were very happy. We got up every day or every two or three days and flew over somewhere, you know. Practicing this was because I was ok just sat in there — me and the other gunner but the navigators and the people like that they had to train in the plane. But we had a good time there, you know. Come down to Lincoln and a couple of pounds — a couple of shillings in your pocket you could have a pint of beer which was very handy because I didn’t drink much then anyway. I don’t drink much now. No. But they was good days and then eventually they sent us out to — well we stayed there, where we were and we started flying to Germany from there, you know and coming back of an evening and it was very nice. If you got back in time you could go to the town itself in Lincoln and have a couple of beers. All part of life in those days. But eventually the war came to an end and on that particular day it was the worst thing I’ve ever seen in my life. We flew over Berlin — literally just above the houses and looking through the windows on the floor was hundreds and hundreds of dead people. Little boys, little girls, mothers and fathers all, all over the place. And also, at the same time the Russians were there doing the same thing and the Americans were there doing the same thing and it was about the worst. It’s a thing I can never forget. Seeing all these little babies, little lads, little, even parents bent up, twisted up, bowled over and stood on, you know. Heart-breaking really but it happened and then we turned back and came home. Then we were sent around various places in England because when we got back to England after the war had finished Canadians, Americans, South Africans they were on the boat going home inside a week. So, all the lads from England and that — they were put in tents in farms to sleep there for a few days till they knew what they were going to do with them and where they were going to send you too. But it was, it was ok you know and we used to go to the local villages and the ladies in the local villages would always give us a cake or, you know something like that which were very very good. And then we were sent to various places because they didn’t know what to do with us. And I was sent down to South Wales to be [pause] I can’t remember what it was but it didn’t suit me and they said oh that’s ok Mr, you know, sergeant as they called us. ‘We’ll find somewhere else to send you.’ And they sent us over then to the other side of the country. What’s it called? God I can’t remember now. Right on the coast. A place where you can go on holidays and all that sort of caper. I can’t remember the name but they sent us there and I learned to type, type there because everything there you know, they’d teach you how to type and I used to type anything that they wanted. And eventually I come home on, you know, on a leash as you might say and I was taken back after a week and at one time they shouted us and said that, ‘We’re going to have to ask you to do something.’ Well, sergeant as it was then. So I said, ‘What is it?’ And he said, ‘We’ve got a man here we’ve got to take over to a prison.’ So that was good that. Just what you wanted wasn’t it? A fella going, ferrying someone over to prison. Anyway, he was a coloured fella had been over here shortly. One of the lads that had come over later on, you know. Anyway, we took him over to his prison and then came back home and started working at the place I was going — learning how to type. Going around places and measuring up for whether they had space for us. And then I was sent to Blackpool before I came out of the air force altogether and spent quite a few weeks in Blackpool. And living, not here but in Manchester. Salford I should say. We used to go dancing in there and going in to the Blackpool Tower, you know. It was a smashing place to go in to in those days. And having a glass of beer I think because we didn’t have much money. And then after about two or three weeks got called in to a place full of overcoats and trousers and shirts and socks. So they gave us a new pair of trousers and new shirts and all well you know all sorts of brand new stuff. New shoes. New socks. New shirts and a nice black suit. And they said, ‘Well you can go home now when you’re ready Frank.’ I said , ‘Well what time is it?’ He said, ‘It’s half past four.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ll leave it ‘til tomorrow.’ Which I did and came home the following day and my little sweetheart was all ready for me then. We didn’t get married then though did we ‘cause we had no money. Yeah. But that’s about it love from the air force point of view. Now, is that any use?

SP: That’s really good, Frank. So –

DS: One thing you didn’t mention was when you did the drops over Holland. The food drops.

FS: Oh that’s right. Yeah. The war was just finishing and we flew over Holland. Just literally over the roofs of the towns. And we took food with us. Well, they supplied food. You know. The air force. And we dropped it to them. Into schoolyards. And then the following day we did the same again but they were all out. All the young kids. They were only about six or seven. All with their big, “Thank you.” “Thank you RAF.” You know. And that was a good thing. And then we moved after that for a while into some farm land and we were dropping food to the farmers then. You know, for the farmers as well as the people themselves and that was another good — good day I think. Something to remember. You know. But the war had finished then and that was about it. Well nothing else apart from coming out of the air force which I did eventually. Came out and they gave us a suit. Well I just told you that didn’t I? A suit and trousers. But then I came home and the day I got home the fire wasn’t in at home because my dad he was working and my mum was — she was [pause] so I had to go around the corner to a coal place and get a coal wagon weighing about two tons, a half a hundred weight in it, and push it over and light the fire, you know. A little bit of happiness but it was, they were good days those, after that. Good days and good nights. But there was four of us in the family and I used to bath on Saturday night. My dad was first, my sister second, somebody else third and I was fourth. All in a little tin bath thing. You know a bath. And it was bloody freezing by the time I got in there you know. Even though it was in front of the fire. But it was good days those and then I eventually found my little sweetheart again and we got married. Ooh a long time after didn’t we? Yeah. A long time after. But she died two years ago unfortunately with cancer. But I’m still here with Alzheimer’s. Have you heard of Alzheimers? Yes. Good. And it doesn’t do anything. I’m quite happy. Happy as a lark. It doesn’t bother me. Alzheimer’s. Wherever I am. So — and apart from that I’ve enjoyed my life. I’ve got a nice little house and don’t drive a car any more. I just have my nice glass of wine with my evening meal, you know. But apart from that we’re getting towards the end I think. Anything else you can think of dear? Not really no. No. You understand that don’t you?

SP: Frank. What did you do after the war? So obviously you came out.

FS: Oh I came out.

SP: What job did you go to after the war?

FS: I was an electrician. And I remember going to a place in Manchester. I did a lot of sockets, you know. Put a lot of sockets in because at that time TV wasn’t coming — it had just started to come out and nobody had a socket on the wall to plug in. so being an electrician I did quite a few of those jobs for people and I think I charged them a half a crown or something like that. Which, a half a crown was a lot of money in those days. And I think I also — I can’t remember what else I did. I did one or two jobs but the electrician was the one I stayed with. And I can’t remember what the others were now. They were jobs that I did for people.

DS: You used to do lots of other electrician jobs for local authorities.

FS: Oh electrical. Yeah. People would come to me and say can you do this and can you do that?

DS: And you used to take me and you would send me under the floor when you were rewiring houses.

FS: That’s right. That’s right. For rewiring. To get the cable.

DS: To get the cable up for it.

FS: That’s when we used to cut the floor didn’t we?

DS: Yeah.

FS: And then drop you under there. Yeah. Oh aye.

DS: [unclear]

FS: I gave you half a crown didn’t I?

DS: I think you might have done. Yeah. And then, and then you went into printing. You became an engraver.

FS: An engraver.

DS: [unclear]

FS: Became an engraver. Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. Yeah. Making the, you made the metal plates didn’t you? And then printed them on to paper. Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. Whatever it was for. Yeah. That was good. That was another good thing that. Yeah.

DS: You stayed doing that. You stayed as an engraver until you retired.

FS: Yeah. I was. That’s right. Yeah. I retired then. Retired. And happy ever since. Yeah. Now, is that enough love?

SP: Thanks for that Frank. Ok Frank. Do you want to tell me about where you were based during the war?

FS: Well the first place was Kelstern is it? That was Kelstern where I were first sent. That was when I was trained. But before I trained I was in Scotland. And I don’t know whether I’ve mentioned this have I? Have I?

DS: St Andrews.

FS: St Andrews. Yeah. I’ve not mentioned this before. Oh, so went up to Scotland. They sent us all over, all over the country. To schools and all sorts of places doing silly, well not silly things but things that was interesting and I can’t remember what they were but we went up to Scotland and we did quite a lot of training up there for flying. And that was at a big Scottish place. I can’t remember the name of it now.

DS: St Andrews.

FS: St Andrews and we was there for five or six — five months I think. Something like that. Training and going out on to the actual golf course and training on there to do things which was necessary you know. But eventually that finished and we came to Heaton Park. Have I mentioned Heaton. I’ve mentioned that so —

DS: And you got crewed up at Heaton Park.

Cath: Yeah.

DS: You met your crew.

FS: That’s right yeah.

SP: Do you want to talk about crewing up at Heaton Park?

FS: Oh of course.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Let me think a little moment. Was it at Heaton Park where I crewed up? [pause] Oh, I think that was Scotland. No.

DS: No. That was Heaton Park.

FS: Heaton Park. Anyway, I went to Heaton Park which was ideal because I lived close by and could get the tram of a morning and get there for 7/8 o’clock I think and did a lot of training in there. How to do this. How to do that. And which was very good. We’d done previously in other places but they always kept up on there. Guns and things, you know. But we stayed there for a while and then have I said anything about going to South Wales? Yes. Oh well that would be it then.

DS: What do you remember about crewing up at Heaton Park when all the gunners were together and all the navs were together and you all became a crew? [pause] Ollie, the skipper, came around and said, ‘We’re looking for gunners,’ and —

FS: Was that Heaton Park? Oh, well that’s possible. Yeah. Heaton Park. That was when I was stationed close at Heaton Park. It was very convenient for me to get home of an evening which they’d let me do you know and get back there for 8 o’clock in the morning which was ideal for my little lady then. But we did pick people up. Literally, put you in a big, a large area with ten aircraft. Not aircraft. Ten people who flew aircraft.

DS: Pilots.

FS: Ten or twelve people who did something else and then the gunners etcetera etcetera. Eight of them. Eight of them altogether. Seven or eight. Yeah. And we picked each other up then and we went over to them and said to the skipper, the pilot and we said, ‘Are you alright for two gunners?’ He said, ‘Certainly.’ And he was a Canadian. A good lad. And he was an old fella. He was thirty, you know. And — but he used to send, or his parents used to send cigarettes and chocolate from Canada. And my old, my dad smoking cigarettes. He’s not here now. Smoked too many cigarettes. And chocolates they’d send over and he’d give them to us you know. So, I’d bring them home and give them to my little sweetheart and we couldn’t be wrong. But that was a good day when we did all that and then we started flying with each other. Sitting in the areas where you were and then they’d take off and you had to do a bit of moving around with, you know, with your guns and that but we didn’t fire but we got used to doing what things were. And that was a good idea too so —

DS: Can you remember the name of the plane?

FS: Ollie’s Bus. Ollie. The pilot was called Ollie something so, we called it Ollie’s bus, you know. And they were all nice, good lads in there. Canadians and there was an American lad in there. And when we went out for a drink, for a beer, of a night-time we didn’t have any money but he went out, you know and sat in a pub but they’d, there was a lot of Yanks where we were down south, they’d just started coming over from America. And the fella we was with was American. He’d leave us and go over to his mates straight away. Which was understandable, you know. But those were good days too moving around England in different aircraft. And when we was in one aircraft, two seater, two engines, I can’t remember what it was now but we were flying in it, doing different things. The gunners trying different guns. Then you would come down and sit down on the floor and as we were sitting down on the floor the pilot said, ‘One of the engines has stopped.’ So, we all had to get down on the floor somewhere and wedge yourself against something while he landed. You know. But he landed ok and it was all part of life in those days. All part of life. Yeah. And well I can’t remember it at the moment. I can’t remember it you know.

SP: About your base at Kelstern — what was that like? Where you were based.

FS: In —

SP: Kelstern in Lincolnshire.

FS: Lincolnshire.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Oh, it was a cracking place that. It was. It was a cracking place. So, we were sent there later on in the war because I think they had space then. And the place that we was in was falling to pieces so they said we’ll send you to Kelstern. And that was — not Kelstern, the one in — what’s the name of the one in York.

DS: Scampton.

FS: Scampton. That’s right. They sent us to Scampton which was the posh one then. So we spent some time at Scampton and went over Germany from Scampton and the other places. You know. Bombed them and that and then the war stopped and things happened then. When I say things happened they didn’t know what to do because all the lads from Canada and America and South Africa they were all going home the following day. So, we were — they didn’t know what to do with us so they sent us to camps which was empty. You know. They’d been full of people at one time and then they were all out then. Empty. So they sent us out of these and we used to go to the various villages then close by. And they used to look after us. Well I say look after us — you’d go in the pub and they’d buy you a pint, you know and things like that and look after us. It was smashing there I think. Those little pubs. Not pubs. Took us to church. I think they took us church — I wasn’t a church goer. And happy life. A happy life and eventually took us somewhere else down south. And I thought why are they sending me down here for because I can’t do what they’re doing here. I’m a man who uses his hands and his brain. And they sent me then over to the other side of the country again and I learned to type. So I was typing things for them and eventually they sent me from there to Blackpool and after Blackpool I was sent home. So that was the end of me as a gunner.

SP: Frank, during the war years were there any particular time when you went up in a Lancaster that you remember? Was there any particular operations that stand out?

FS: I’m trying to think.

DS: I remember you telling me once you got caught in the searchlights over Berlin and you had to corkscrew down.

FS: Aye. That’s right. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right over Berlin. And there’s usually about a few hundred that was going over there from here, you know and this particular night they got the old guns. Not the guns going. They get the lights, headlights. The —

DS: Searchlights.

FS: Searchlights. They’d got the searchlights going and the, God knows, underneath so they were following us all the way and then the German aircraft — they came after us and we had to do a bit of flying like this, you know. And fortunately we got away with it that particular time. And we did two or three over Germany. Well more than that two or three. We did about half a dozen, a dozen or so I think over Germany. And each time we were flying over we’d see somebody in the distance flying underneath an aircraft. And it was dark because it we always went over at night and as we got a bit closer we could see that the plane underneath was a German plane.

DS: A fighter.

FS: And it had guns pointing upwards and all he did was press the button and brrrrrm and kill the plane itself with all the lads on. So, you had to watch out for that which we did. But these things happen in war and not much you could do about it and I was lucky to get back alive. That’s the way I look at it, you know. And very very nice. Very nice I thought, that there was always some hot food ready when you got back. You got back at 5 o’clock in a morning you’d always got a breakfast ready for you. And somebody would shout, ‘Do you like your egg?’ I’d say, ‘No, I don’t want my egg.’ ‘Well, I’ll have it. Pass the plate over, you know. But I’ve never liked eggs. Not eggs. Something I don’t like. I can’t remember now. What is it I don’t like?

Cath: Onions.

FS: Onions. I hate onions so and I still hate onions and I’ll tell them now, so. Those were good days and then there was a lot of moving around. Then I think I’ve told you about this. Moving around. Yeah.

SP: And when you were at Kelstern you said that you had to sometimes sit at the side of the runway with your gun.

FS: Correct.

SP: What was that for?

FS: Well in those days it was always evening when the Germans came over. Like at the same time as went we over there. And the aircraft, there was usually about four aircraft, five aircraft could be six aircraft coming at a time, coming in and we sat on each side with our brrrrrr and there could be, and there had been, after the last aircraft came in a German aircraft would follow them in and shoot at him as he was landing. So, they put two of us, one on each side, to keep our eyes open after the last one came in because they, and we shot at them and I think we missed them, you know. But it stopped. They stopped coming in after that. Which was another part of life isn’t it, you know. But a good life. I’ve had a good life and I’m still here which is the main thing, you know. Anything more you want love?

SP: Is there anything else you can think of you that you’ve not had the chance to say or anything?

FS: I’ll just have a think.

SP: Yeah.

FS: Yeah. Turn it off.

[recording paused]

FS: Ready.

SP: Ok Frank. You were talking about your crew and other crews. Is there anything that stands out about –?

FS: Well there was one member of my crew. The crew I was in. And it was too much for him. Even training was too much for him so he did a runner up to Scotland. I think he was a Scots fellow. I may be wrong. But he’d gone up there possibly because it was easier to find somebody up there. A place to go to wasn’t it? Scotland in those days. But eventually the police found out, the RAF police found him and brought him back and he was brought out on to the space that there was there and all the people in the area itself. When I say the people, all the staff, you know, all the people that worked.

DS: All the crews.

FS: The aircrew. Not aircrew. All the RAF people. They all came out and he was stood there and then his medals were dragged off and he was taken off by two policemen then and sent somewhere else. As a, as a thing, you know. Like — it was like being taken to prison isn’t it? But I can understand it because it was a terrible thing to have in your mind. But I’m not, it was in my mind but nowt you could do about it. Nothing you could do about it, you know but it was good — looking back on it it was a good thing and it’s kept me going and still here at ninety two. So not bad going is it?

SP: No.

FS: No. I know.

SP: Yeah. Frank if I can thank you for your time. I think that’s been great. Thank you very much. And thank you Dave as well for helping out with that. So —

FS: You enjoyed it.

SP: Yes. Very much so. Always a pleasure to hear stories.

FS: Like this. Have you heard other stories like this?

SP: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Every one’s slightly different but —

FS: Oh, they’re all slightly different but they have the same —

SP: Still, great, great stories. Yeah. Yeah.

FS: The same outlook as we all had as you might say. Yeah. We may not come back from this one, you know. Every time you got in the plane you’d think by Jerry am I going to come back. And you’d see somebody. You were flying over with them and all of a sudden you’d see him with a half a wing blown off.

DS: The thing that sticks in my mind —

[recording paused]

FS: Fills it all up doesn’t it for you?

SP: Right. Just a couple of bits to add Frank. You were just chatting then after we’d finished about your nicknames that you had during the war which I thought were really interesting. So, do you want to let us know about that? Your nicknames and why you had those.

FS: Algernon Montague Simpson wasn’t it?

DS: That was the name you gave yourself.

FS: That’s what I gave myself. Yeah.

SP: But that wasn’t your name.

FS: No. Frank. I was Frank. Algernon Montague Simpson. Yeah. That still comes my way. A while ago now. Yeah. Here you are Frank how are you? Tea and coffee and that. Yeah.

SP: So, all your crew knew you as that.

FS: Oh yeah.

SP: Yeah.

FS: They knew I was Frank but I used to call, well they used to say Frank Algernon you know. I don’t know why it came up. These sort of things. But they do in your life don’t they?

SP: Yeah. And then you had a nickname because you were quite slim during the war.

FS: What was it? Yeah. Skinny bugger.

Cath: Satchel arse.

FS: Satchel arse. Yeah. There was no room for me. I used to slip off the, where we were sat with the gunnery. Sat there I used to slip off there. Oooh get back on again. Yeah, I was only a skinny bugger then. I still am really. Oh they were good days those. Good days. Another thing that they had in those days was they had a toilet in the aircraft. And I was sat in the, where I usually sit and saw somebody walking down. And I saw him get on the toilet and do what was necessary and it was the pilot. He couldn’t do anything else but go to the toilet [laughs] No. They were good days those. Good days. Still comes through my mind occasionally. Even more so now. Yeah. Yeah. But that’s, yeah, cracking that. Well I can’t think of anything else now.

SP: That’s great Frank. So, I’ll just thank you again for that. And thank you Dave.

FS: I’m going to charge of course [laughs]

SP: I’ll let them know.

Collection

Citation

Susanne Pescott, “Interview with Frank Simpson,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 4, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/8823.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.