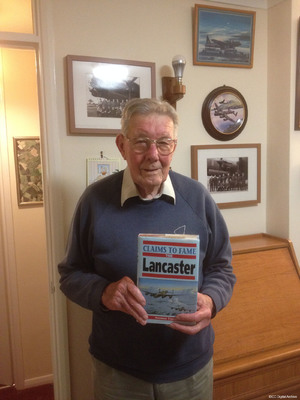

Interview with Sidney Bunce

Title

Interview with Sidney Bunce

Description

Sid was working at a garage and a member of the local Air Training Corps when he volunteered for the Royal Air Force. At 18, he was kitted out at Padgate and trained as a flight mechanic on engines at Blackpool. Sid describes his 18-week training course. He was posted to 115 Squadron at RAF Witchford, joining a group responsible for two aircraft. Sid was promoted from aircraftman second class to aircraftman first class. 195 Squadron was reformed to include 115 Squadron. Sid transferred to RAF Wratting Common where he became a Leading Aircraftman. He describes their participation in Operation Manna and Exodus. When the squadron disbanded, he went for a short time to RAF Mildenhall and was, initially, put forward for an overseas posting. However, he instead went to RAF Wing, and subsequently to RAF Silverstone and RAF Swinderby as each closed. Sid details the work they carried out, depending on whether or not they were night operations, and outlines the different ground crew roles. He tells of two aircraft being shot down by a German night fighter on their return to base. His aircraft, however, managed 105 operations. He would carry out air tests in the aircraft. Sid talks of Wellingtons and Lancasters which he worked on, and his admiration for Merlin engines. A V-1 fell near the airfield at RAF Wratting Common. Sid was demobilised at RAF Kirkham in April 1947. After the war he drove for United Dairies and the London Brick company.

Creator

Date

2016-11-08

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

02:01:44 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

ABunceFSG161108

PBunceFSG1609

Transcription

CB: My name is Chris Brockbank and today is the eighth of November two thousand and sixteen, and I’m in the village of Thornborough near Buckingham with Sid Bunce, and we’re going to talk about his time as an engineer in the RAF. So, what were your earliest recollections of life Sid?

FB: My early recollections, well, I was born in Lower End, Thornborough and, from then on, I stayed there until I was, ten years old and then by this time I had a brother Harold, he’s eight years younger than me, and er, we moved out of the Lower End into Bridge Street in Thornborough, and, Mother died in September nineteen thirty-six. I stayed with my Father, my brother he was, he went around to the police house where my Grandparents on the Baker side, my Mother’s side, they lived, and he was bought up with my Grandparents and an aunt, who was still unmarried and living there [pause] I was, I started school at Thornborough and I stayed there until I was eleven years old and took the eleven plus, and I, and I failed the eleven plus in so far as I got half way through, and in those days, I think if you, there were so many, erm, seats set aside at the [unclear] school, so that if you, if you got, if you didn’t get the full, er, the full marks that were required you could pay to go to school, but obviously my Father he couldn’t afford to do that. So, I went to what was called then, the Buckingham senior school, I stayed there until I was fourteen. When I left school in July, the war broke out in September nineteen thirty-nine, I wanted to be a motor mechanic and one Saturday afternoon my Father and I went up on the bus from Thornborough to Buckingham and saw a Mr Ganderton, who had a small garage. Unfortunately, the job had gone by the time we got there, so, went up to Cantells in West Street where my cousin Cyril worked as a shop assistant, and from there, he, my Father asked him if he knew of anyone who wanted a boy, and he said, the only one he knew of was Bert Campion who was a manager of E C Turner. He said, he wanted an errand boy, and er, so, we went to see Bert Campion and he asked me a few questions and er, I, he asked me when I could start, and I started work there on the Monday. I had about, I think it was, [pause] roughly about four months and I used to have to do the rounds, the deliveries, on a, each day in any case, and on this particular Saturday, Mr Campion he said, I want you to go across to Adcock’s and I want you to get a white jacket and an apron, and I did that and when I got back he said, I’m going to start you off serving in the shop, so for about a month, or so, I can’t remember, about a month anyway, he, only had one shop assistant and he sacked him and he put me into the, promoted me into the, as a shop assistant. I was very grateful to him in actual fact, because he taught me the bacon trade, and if you, I think if you gave me a side of bacon I could still, I could still bone it and cut it up as a, anyway, I stayed there until, I started to work there at eight shillings a week, that’s 40 pence now isn’t it, and by the time I was sixteen, I was getting a pound a week, and one of my best pals he was at a different place earning more money than I, but eventually, when I started work my Father was concerned for what I would do for a midday meal, because I was working in Buckingham, and I had an aunt and uncle who lived in Buckingham, and I went there for my lunch, from then until I went and joined the air force. But, [pause] I was upset in so far that I wasn’t earning very much money, and eventually my uncle said that they wanted a boy up in the garage at the United Dairies at Buckingham, and I started there, and I was in, I started in the garage. I learnt to drive on a milk lorry, I used to round on the milk, collecting milk and from then on [pause] Where have I got too? [pause] Yes, I started work at the United Dairies and I stayed there until I was called up in the air force, but in between times, the ATC was formed at Buckingham and I joined the ATC, and er, when I was seventeen I volunteered for aircrew, but I wanted to be a flight engineer, and actually the flight mechanics engine course which I did, I believe that was one of the training for flight engineer. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I didn’t, I was put on the volunteer reserve, told to wait for my call up, and I was eighteen on June the twelfth and I was in the air force on August the twenty four, joining at Padgate where I did what we called the square bashing and after that I was er, went to Blackpool, stationed at fourteen eighteen, er, 48 Osborne Road [unclear] shore and erm, we were taken by bus or coach to Squires Gate where we did the training as a flight mechanic engines. When I, it was an eighteen-week course and when I passed I was posted to 115 Squadron at Witchford. [background noise] I stayed there until 195 Squadron was reformed and they took our flight, C Flight of 195, er of 115, and called it A Flight of 195 and after the squadron was fully operational, for a month there were two squadrons operating out of Witchford, and then, 195 Squadron was transferred to Wratting Common. Theres an interesting story about that because there’s a Wratting and there’s West Wickham and other villages, and apparently, this is true anyway, at erm, when Wratting Common was opened in 1940, 1943 they called it West Wickham, and from my understand, the signals were getting crossed with High Wycombe, which is Bomber Command Headquarters, and so they renamed it as Wratting Common. I was there until the end of the war, when we were, when 195 was disbanded, from then I went to Mildenhall for a month, then I was put on an overseas posting, went to Blackpool, but did, was taken off before we were drafted out. Then I was posted to Wing and when Wing was closed down I moved to Silverstone, and we were the last unit in Silverstone when they closed Silverstone. We went up to Swinderby and then that was the end of my service, I went to Kirkham and that was where I was demobbed on April the first 1947.

CB: Okay, we’ll pause there for a moment

[recording paused]

CB: So, that’s a good trail of what you were doing. When you joined the RAF you’d been in the ATC so how did that prepare you for what you, what came next?

FB: Well, in actual fact, I joined the ATC because I wanted to go in the air force, I didn’t want to go in the navy, into the navy I’m not a lover of the sea, not sailing anyway, and as far as the army was concerned and after what I’d seen of my poor Father went through in the First World war, in his health. I was interested in aircraft anyway, and so I joined the ATC. We had a very good warrant officer in charge, Mike Westly, he was a very good instructor and taught us the basics of learning to, er, foot drill, not rifle drill, we didn’t have anything to do with rifles, and so of course when I went on my interview for the air force I didn’t have any problems at all with the foot drill. Rifle drill came quite easy, and it, think it really put me on a good footing for service in the air force, in the air force

CB: So, when you were doing your initial training, erm, then what did you actually do in that initial training at Padgate, activities? You had to do the drill, but what did you do overall?

FB: Well, erm, [pause] let me see

CB: So, it was learning about the RAF?

FB: Yes, we had to, you know, get kitted out and obviously we had to do our spit and polishes, record it

CB: Of your boots?

FB: The erm [pause] I remember we have to make sure with our shoes that they were highly polished and the buttons, we used to have to clean our buttons and [unclear] issued with erm, a kit for cleaning and also for, if I remember rightly sort of doing simple needlework, in so far as sewing on badges or whatever, that kind of thing

CB: And cleaning your

FB: We had some, we had some sport, that actually, that, if I remember rightly, that was an eight week course, yes, eight week course, actually we were there, I was there ten weeks, but that was the fact that we didn’t start training straight away, for whatever reason, I don’t know, I also know that Warrington was the nearest town and we weren’t allowed to go in there, apparently there’d been some problems with the Americans, [laughs] think fighting or whatever, something like that, so I think it was actually, we were put out of bounds, I didn’t miss that anyway. But after the, after that, if I remember rightly, we came home on seven days leave and then had to report back to erm, Blackpool

CB: So, Blackpool was the base for technical training for you, for engineering?

FB: Yes, well yes, Blackpool, we were bused down to Squires Gate into the airfield, and we did our training in one of the hangars, which consisted of, that was eighteen-week course, it composed of fortnightly VV’s as they called it, verbal verification, and the first fortnight we were given [laughs] a lump of metal and a file, and we had to file this lump of metal into whatever shape we were told to do, and that lasted for a fortnight, and after the fortnight you had a verbal verification. So, asked various questions on the, what you’ve been doing for that fortnight, and if you passed you went on to the next stage, if you failed you stayed on and were put back for another fortnight, and if you failed you were kicked out. Fortunately, all of our entry, not one failed. But, after the first fortnight, um, oh I’m a bit hazy on how it worked now, but the next, the next fortnight you had another verbal verification and you had to get a percentage of the questions asked, right and then you went on to the next stage. And I well remember, that eventually, we got to where the stage where we had to dismantle an engine, and one of our entry, he always had the top marks, most of us used to struggle through, and get through the minimum marks required to continue. He was always on top and he, and when we came to taking the engine, dismantling the engine, and we were taught how to take it apart and put them all in sections so that you knew when you went to replace it and put them back, he, he was hopeless, but anyway he did manage to get through and eventually at the end, the last fortnight, I was, erm, revision, and so, we revised all that we’d been trained to do and erm, then you had to go and, if I remember rightly, there was all these various parts out on benches and you had to identify them and what they did, and all the rest of it, and I passed out as an AC2, which meant, the majority of us did, but this, this, funny enough, this chap who wasn’t very good at dismantling engines and reassessing them, he passed out as an AC1 [laughs] and he went straight on to train as an instructor. But, I was posted to 115 Squadron [pause]

CB: So, you come to the end of the course and what do they do as a formality in documentation and parade?

FB: Do you mean, I can’t remember having anything, anything to say that you, I can’t remember, I don’t think we had anything to

CB: I was just thinking of when you get posted to a squadron, they want to know you’re competent, and you might do that with a passing out certificate

FB: I can’t recollect having a pass out certificate

CB: Might be in your service record, we’ll have a look. Okay, so you passed out there, there was a marching parade was there, to mark the end of the course?

FB: Er, oh yeh, well of course, so yes, we were [laughs] during the course at Padgate, then you had the parades

CB: Yeh

FB: On the Sunday, you had the parade on Sunday and so forth, and the band, I used to like, we had a pipe band, I used to like marching behind the pipe band rather [laughs] than a brass band or a silver band

CB: So, you are formed up on the parade square, there are separate sections, and the ones who are passing out are supported by the following courses, is that right? And then you get reviewed by a reviewing officer [pause] and then you march past and the reviewing officer takes the salute, is that right?

FB: Oh yes, we had to march past and salute, yes, I think that was [pause] as far as I remember, and that’s all it was

CB: And then, after that, did they give you a bunfight?

FB: No

CB: Nothing, just disperse

FB: No, we just passed out and got on with it

CB: Yeh, how soon did you then report to the squadron, 115?

FB: I came, yes, but I think I came home on seven days, I think it was seven days leave and then [pause]

CB: So, when you

FB: Yes, I had to, I had to report to RAF Witchford [pause] now I had, had a railway pass obviously, and had to go from Bletchley to Cambridge [pause] I can’t remember the next station

CB: Cambridge up to Ely

FB: Ely, that’s right. Oh yes, then we, we picked up, erm, a lorry

CB: What was the rank and status that you had then?

FB: I was AC2, AC2. While I was at Witchford, I had to, for erm, sort of erm, promotion if you call it that. I had to, an interview and was asked various questions on, well, what you knew and what you were capable of, and I passed for that, and I was AC1. I was still AC1 when we left Witchford before Wratting Common, and there again, one of the sergeants after we’d been there, been there a while, I took another exam if you like, and I passed that and became a LAC, and I was an AC for the rest of my service

CB: When you arrived at Witchford, what process did they put you through in linking you with the squadron?

FB: Well, one, obviously gone on parade and I can’t remember, but I was sort of allocated to this group with a, I’ve forgotten the sergeants name now, but erm, so I joined this, I joined this, basically the group, the small group was responsible for two aircraft, you know the pans were sort of, not too far away from one another, based round the airfield, and

CB: The pans are where the aircraft are parked?

FB: Actually stand, yeh, yeh, and as I was a sprog, newly trained, the sergeant, he put me with an older fitter, not much older, but name of Malcolm Buckingham, and we worked together on the same plane, from then right through until the end of the war, but, the sergeant, he was a very, very, very good sergeant, he knew exactly what you were capable of and he wouldn’t let you do anything until he knew you were capable of doing it, and the one of the things that you did have to make sure of when you was pulling the chocks away, to take, that you run backwards and not forward otherwise you [bang noise] you run into the propellers. Well, we did our daily inspections, DI’s, and obviously we did all the checking. If there had been any faults reported, minor faults that we could do, out on the flights, we did, if they were major they used to have to go into the hangars. But, when, as far as the operations was concerned, when, if you, normal working time was erm, eight till five, but if you were on what they called take off, you still worked from eight till five, then you went down to, well to have your meals, but you had to get back on to the air, onto the airfield an hour before take-off [pause] The crew, when the air crews were bought out and left in their different planes, I worked on A4D-Dog and the other one was A4C- Charlie, they were the two planes, but basically what happened, the aircrew came out and obviously they would have a look around, to check that everything was okay, and also inside, and when it was time to start up, one of us used to get up under the undercart, as we used to call it, under the wheels where the [unclear] gas pumps were, and there was two [unclear] gas pumps, there was one for the starboard inner and one for the starboard outer, one for port inner and one for the port outer, and you jumped up and one of you went up there and primed it, the other stayed on the trolley where the batteries were on the trolley, and when the skipper was ready to start up, he used to, well, obviously they were all, all, night operations, so if it was dark we used to get the skipper to just put his Nav lights on and off, so when I used to do the priming and when I used to press the button, and the start all four engines up, and they did the run up, we used to, when we were doing the DI’s in the morning we used to take them up to about three thousand revs a minute and then test the mags, switch each magneto off one at a time, and if there was a revs drop more than one hundred revs, then we had to do a change, a plug change. When they done there, when they done they’re run off, well, we used to take and pull the chocks out and away they went and we used to wait up there until all of them had taken off, and then as far as you were concerned you were finished until the following morning. But, if you were on all night as they called it, then the same procedure happened in as far as I you get up an hour onto the airfield, an hour before take-off and when they’d all gone you were able to go back to your billet or to the NAAFI, you couldn’t obviously, you couldn’t leave the airfield, and then you were told what the ETA was, and you would get on up to the airfield, an hour before they were expected back. I used to say to erm, well you, the, whoever you, whoever you see [unclear] I used to say to them, ‘flash D in morse, or C for Charlie’, then you knew which pan to put them on, and when they came and you put them on, on, on the pan, you used to get the ladder out, and they used to come out and you used to ask them if there was any snags, and if there were any snags, then you went and reported them to the flight office. After they’d gone, you used to go back and put the locking bars in, chocks underneath and shut it up and that was your, then you were finished, then you could go back and you had the following day off

CB: When you talk about locking bars, these are the effectively the clamps that stop the control surfaces,

FB: Stop it, yeh

FB: So, in the wind they wont

FB: That’s right

CB: Flail around

FB: That’s right

CB: Right, okay. Now as an air mechanic, what was your specific role, because everybody mucked in, but actually you had a specific, which was engine was it?

FB: Oh, engines

CB: Yeh

FB: Yes

CB: Right

FB: So, you see there was erm, there was two engine mechanics if you like

CB: Yeh

FB: And, a rigger for air frame, sort of for each, and obviously the, all the ancillary, so the armourers, the electricians and all of those, and of course did their own, their own job [pause]

CB: For each aircraft, so that there would be a Chiefy, he’d be a flight sergeant?

FB: Well

CB: Or what? ’Cos the gang effectively

FB: The gang, it was a sergeant

CB A sergeant, yes

FB: Sometimes there was two sergeants and a corporal, it just all depends how it was, but erm, yes, there was a sergeant in charge of you

CB: Yes

FB: In your little gang

CB: So, in the team, the gang, you had a sergeant, two engine mechanics, a rigger, an electrician?

FB: Well, there was a, yes, an electrician and of course

CB: And the armourer

FB: But when they bought the bombs out

CB: Yes

FB: The armourers, they, they obviously, they did the bombing up

CB: Yeh

FB: Winching up into the bomb bays

CB: So, the bombs came on trolleys?

FB: [inaudible]

CB: How did they get the bombs up into the bomb bay?

FB: Well, they put them, obviously the bomb doors were open

CB: Yep

FB: One of the armourers would go up into the plane and they sort of winched them up, they’d draw them up on

CB: An electric winch?

FB: Yes, draw them up on that, and then when they were secured, erm

CB: Where was the winch operated from?

FB: More often, but it all depends what the target was going to be, where they were going, but generally it was, it could be a load of incendiaries

CB: Yep

FB: And then perhaps a four thousand pounder or an eight thousand pounder, and then they got larger, but that was generally the load. Sometimes it would be thousand pounders, it just all depended on what the target was going to be and obviously the crew would never tell you where they were going, you wouldn’t expect them to, but they might say where they’d been but very, very, very rarely, you could get a rough idea where they may be going or what area, because of the bomb load and the fuel load, because depending on, I think if I remember right, erm, Berlin it would be almost full tanks, if I remember right, I think the Ruhr, depending where it was, sometimes it would be about seventeen fifty gallons, coming er, coming nearer to home it would be fifteen, yeh, fifteen hundred gallons, if I remember when we were [unclear] up for D Day, we were doing two ops. We used to have to get up at four o’clock in the morning er, and get up on the airfield, 1944 that was a really cold winter [laughs] we had to, well, the engines, we didn’t, we weren’t too badly off because we’d put a load of lanolin grease on the leading edges of the props and the erm, main plane, but the poor old riggers they used to have to go and de-ice the Perspex and all the rest of it [laughs] What that consisted of, we engine ones used to have a can of antifreeze, a drum of antifreeze and a stirrup pump, and the airframe, they used to have to go up onto the, onto the, on the main plane obviously, and erm, they used to have to spray the Perspex to clear them, that was quite a job

CB: What did they do? How did they clear them, they didn’t just scrape them did they?

FB: No, it was just a stirrup pump, you see, you spray it

CB: Yes, but what were they spraying? Was that antifreeze as well?

FB: Oh yes, because they got to clear the you know, the cockpit

CB: Yeh

FB: And the mid upper gunner, and all the rest of it. Tail end Charlie he was [laughs] I wouldn’t have wanted to do that job

CB: The rear gunner?

FB: Hmm, no

CB: You mentioned about the leading edges, so on the props and on the leading edges of the main plane

FB: Lanolin grease

CB: Right, yeh, right, so you spread that on with your hands or best with stick, yeh, okay, and that worked, did it?

FB: Oh yes, that worked, yeh, yeh

CB: What about things like the Peto head, you really couldn’t put anything on that could you?

FB: No, no

CB: Okay, so starting, you’ve got a trolley ack

FB: Yeh

CB: How do you go about starting?

FB: Well

CB: So, the trolley ack being the trolley accumulator

FB: Well, that’s plugged in, its, its plugged in, as I say you go up

CB: Into the engine bay, is it?

FB: Hmm

CB: Right

FB: Then, one of you, as I say, went up on the on top of the wheel in other words

CB: Yes

FB: Undercarriage, and there are these [unclear] gas pumps, and when they, the skipper was ready to start up, you used, you used to prime them, er, basically it was more like a choke on a car I would think, but you used to give them, they probably need perhaps about six or eight pumps, each pump, and while you were doing that, of course the, your mate, he was pressing the button to, where it was plugged in, to turn the engines over

CB: What was this stuff that gave the extra urge, it wasn’t an ethanol something, what was the material, what was the erm, fluid that you were pumping in to give it that surge of

FB: Oh, that was, that was petrol

CB: It was just neat petrol?

FB: Hmm

CB: Right

FB: ‘Cos you got your, obviously you got your blowers as we used to call it, it’s at the trunk, that erm, built it up

CB: Yeh

FB: You got your mixture and, away she went

CB: So, what was the engine starting sequence?

FB: Erm, you start the starboard engine, starboard engine, inner engine first

CB: Right, what

FB: Where the hydraulics are, so if that didn’t, obviously if you hadn’t any hydraulics you didn’t have brakes or anything else. And er, [unclear] it all depended on what, on what the pilot wanted to do, but that one was first, then probably it would be the starboard outer, because if you started off on that side, well obviously, you’ve got to go round to the other side to start the others up, so, yeh

CB: So, you moved the trolley ack each time or was there one trolley ack each side?

FB: Well, no, you moved it and plugged it in

CB: Yeh, okay

FB: I nearly always went up on, I nearly always went up on the wheel and did the pumping

CB: Now, this is pretty close to the propellers, so what was the procedure to make sure people didn’t walk into a propeller?

FB: Well actually, when er, when all the engines were running and they were ready to move off, you had to make sure that your chock, it was no good you see, you had the rope

CB: Attached to the chock?

FB: From the, attached to the chock

CB: Just to explain, the chock is holding the wheel

FB: But, the point is this, it was no good if you, where the knot was

CB: Yes

FB: Where it was knotted, it was no good putting the knot and straight through there, because you wouldn’t move them, you could not pull it out, ‘cos normally the wheels would move just a little bit onto the chock you see, so what you had to do, you put your chock and you run your, from here, round the front of the chock and back there, and then when you pulled it, you see, that pulled it out like that, if you did, you couldn’t get it out, if you did, it was a straight pull, it had to go round and pull it out

CB: Right, so, the

FB: And when you did that, as you pulled it, you ran backwards, no good running forwards, you ran backwards and that was it

CB Right, and there’s a chock each side of the wheel?

FB: Oh yeh

CB: And when

FB: There was, just in front of the wheel, but each wheel had the chock obviously

CB: Not just at the front

FB: Yeh

CB: Okay, at what point would the chocks normally, would they have been put in? When would the chocks normally have been put up against the wheel?

FB: Oh well, you put the, when the er, a plane for instance would come back afterwards, you, you put the chocks on straight away

CB: When its landed?

FB: When its landed, yeh

CB: So, the plane is a light at that point and when you start it up its heavy because it’s got the bombs and the fuel on, so that pushes the tyre down onto the chock

FB: Well, just

CB: Making it difficult to pull away

FB: Yes, as I say it was straight pulled, it wouldn’t come

CB: No

FB: You had to do it then and there

CB: Right

FB: Yeh

CB: So, at that point what does the ground crew do as the aircraft starts up to taxiing?

FB: Well, the er, as I say, when er, when er, they started up, done the run up, it was out turn to go off round the perimeter track to the runway, then erm, those of you there, you always used to stop until they’d all gone off

CB: Watch them go?

FB: And er, well, there’s a little bit I’ll tell you about

CB: Okay

FB: Er, later on, erm, what else, as I say, if there were any snags, but you went back to the flight office anyway

CB: Right

FB: When both planes were back, and you went and you reported, and of course the crew had been taken off for debriefing, and, when you, when your two planes are back you were finished, you could go back. You used to go back and have a meal and then go into bed and have the rest of the day off

CB: Yes, I’m just trying to get the sequence here because, to give people an idea of just how it went. So, at take-off, you, they’ve done the run up, checked and tested the engine, run up, chocks away

FB: Yes

CB: And then, what do you do as a ground crew, do you watch them go and then go for meal or how did that work?

FB: Just watch them, yes

CB: ‘Cos the

FB: I think everybody, I was taken all round the circuit

CB: Yes

FB: We always used to stop and watch them go off until they’d all gone. There was one incident [pause] obviously they, when they took off they used to go round and then they used to rendezvous where they had to go before [unclear] rendezvous to go out on their raid, and one night there was a [laughs] an awful crump and er, they erm, there was a four thousand pounder, something had gone wrong and it

CB: A cookie fell out?

FB: It fell out, yeh [laughs] oh dear, well, these things happened. The worst thing that happened, I’ve got it, I marked it there to show you. German night fighters used to, would follow them back. When I was with 115, they shot two of our planes down, because obviously they didn’t always come back together, they’d come at intervals and you stayed there until your two planes had come back. Fortunately, touch wood, old Buck and I, we never lost a plane, but that was exceptional er, I suppose, but this particular night they, you see, what they did when they came back, well, they had to wait their turn to land, and so, obviously they used to do a circuit, and it was on one of these circuits that this plane was coming in to land and er, this night fighter shot it down, they were all killed, they all lost their lives, both crews, they both, but at different intervals, the same night, we lost two

CB: What was the reaction of their individual ground crews to the loss of their aircraft?

FB: well, I don’t really know because I never lost one, but I suppose they’d be, I presume they’d be allocated another, I don’t really know about that

CB: I wondered if it was spoken about when you were in the NAAFI or somewhere, or did people ever talk about it, or did they just keep on?

FB: No, no, they didn’t talk about it, no

CB: Right, now what about accommodation, what did you have in?

FB: We were in nissen huts

CB: Right, how many in a nissen hut?

FB: Oh, what would it be [pause] one, two, three, four [pause] about twelve I think

CB: And how was the nissen hut heated?

FB: Oh, a stove, a coke stove [pause] Ah, [emphasis] we used to have a stove, up in the, in the erm, [pause] in the hut, where we, you know, kept the tools and all the different stuff in there, there was a stove in there, to sort of, keep it warm, and [pause] there is, have this coke, I mean, sort of filled it up, lit it and basically that was [pause] I mean for a lot of the time, for a lot of the morning anyway, erm, you was still working, you know, you were doing your DI’s you see, daily inspection, coal was off and of course with the Lancaster, you had to get up on these gantry’s because there was no, it was different to when I was on Wellingtons, had to, when I got round to [unclear] and Silverstone, I mean you could get on there, used to slide down the back, down the main frame on the Wellington [laughs] we used to get up there, on a Lancaster you couldn’t, oh dear

CB: So

FB: 44, that was a cold winter

CB: So, how did you deal with the cold on the flight line, in other words, out on the dispersal?

FB: Well, you, you see, you had mittens on because you can’t really feel with gloves on, it, you had to keep your fingers sort of [inaudible] [laughs] the weirdest thing was ever, if you had to do a plug change, and if you happened to drop a plug down in the trunk, of course they were v engines, you see, you could drop one down there, and that used to be a dickens of a job to get the blooming thing back out [laughs] to put it in, ah, but, at least they say live and learn, and you did

CB: You talk about a plug change, that’s because you’d get misfire was it or was there a sequence where you changed all the plugs?

FB: Yeh well, if the er, if the, obviously your magneto, it’s like a dynamo, in so far as supplying the spark

CB: Yes

FB: But if er, they dropped back there, then obviously, it’s erm, you wouldn’t need a, it wouldn’t need a, very doubtful it would be the magneto, so it would be a plug or plugs, that weren’t firing properly to do that. We didn’t have a lot of trouble, I mean that old Merlin, it was a lovely engine to work on, no problem at all really

CB: In what way was it good to work on?

FB: Pardon?

CB: In what way was it good to work on?

FB: Well, it was [pause] the construction of it, mind you, everything it was bonded, so, when you, when you took your coverings off to do your, check them, you had to check them, every one of those, and if there was, if there was any bonding broken, then obviously that had to be replaced, you see, it was for erm, obviously for the electricity, for it was a static electricity, you didn’t want anything like that, with the petrol, I mean that was a hundred octane petrol, so that was green and that was pretty horrible [laughs] oh dear

CB: Did anybody get fires on the ground?

FB: Fires?

CB: Engine fires or any kind of?

FB: No, erm, now where was that? [pause] I think that was at Wratting Common. The plane had been, been in the hangers for overhaul or whatever, I don’t know what, and the, they’d obviously had the under propeller off for some reason or other, and when they bought it out and they started it, it come off, flew off, erm but I only, I didn’t actually see it, I heard that it happened, but er, say, that plane A4D-Dog, that’s the one where this crew did a complete tour of ops, actually, that went on to do a hundred and five ops

CB: Did it

FB: But, by the time that stayed behind on, because it was on C-Flight, by that time, er, when we were, 195 was reformed, we had worked on it, Buck and I worked on it and I think they had done, either fifty nine or sixty ops, but that went on, on the history of it, to do one hundred and five, which erm, when, well when the, of course I was at 195 at Wratting Common then, but erm, when the Dutch, when they were in that, after the invasion had started and they were liberated, we went on what they called Manna, which was dropping the food supplies to them. So, we went on that and then after that, when that had finished, we started bringing back the prisoners of war

CB: Operation Exodus

FB: Yes

CB: Okay, let’s just pause there for a moment, you just have a breather

[interview paused]

FB: There’s one thing

CB: These gantries you had to use?

FB: We never had to do was wear a ring

CB: Ah

FB: Because if you wore a ring and you slipped, that would rip your finger off, you see, so, I never wore a ring anyway, I’ve never ever worn a ring in that case, but you never wore a ring. It’s like a lot of things, its common sense, I mean, there are things but obviously you shouldn’t do but if you do, well you suffer by it, really. We used to, well, I mean, oh crikey, I was only eighteen [laughs] eighteen, nineteen years old, I mean, we used to clamber up them no problem at all [pause]

CB: How safe were these gantries you used?

FB: Oh, they, they were safe enough, if I mean er, it was just a matter of climbing up on the, onto and getting on the platform, yeh they were safe enough, you didn’t have, well I didn’t hear of anyone getting injured by falling off them or anything like that

CB: So, on the flight line on the dispersal, you had a team of people we talked about just now, what would make it necessary for the aircraft to go into a hangar?

FB: If they had a major, for instance if there, had been on a raid, and they were badly shot up or anything like that, well, obviously they would go in, into for repair, er, if an engine, well, if anything really, but engines in particular, if there any major fault or [unclear] then you couldn’t do that, that was somethings obviously, you could do minor repairs on the flights but if it was a major repair well it had to go into the hangar because you just wouldn’t have the facilities or anything else to do it

CB: What about engine changes?

FB: One thing you used, well, as far as engine changes were concerned, I never experienced an engine change because as I say, the planes that I worked on we didn’t lose any, that Malcolm Buckingham and I worked on, but erm, I remember, if, if, if they had been out on a raid and they couldn’t get back to their base, [background noise] there was at Woodbridge, there’s two airfields, one was the Americans on and the other one which was what, we used to call them the crash land station, basically it was one plane that couldn’t get back to their main airbase, but they could get down there, and they used to go down there. And, what happened in that er, base, although obviously I never experienced it, but if a plane didn’t get back to, for instance, Witchford or to Wratting Common, if they didn’t get back there then the crew that serviced them they used to go over to service them and put them right and then they flew back to the base

CB: And, did that ground crew take, erm, road transport or did they get flown there?

FB: I think they took road transport. I’m not too sure about that because as I say I never experienced it but that’s what happened

CB: How many times did you have the opportunity of flying, in the aircraft you serviced?

FB: Well, no, if erm, if we are doing an air test you could go up if you wanted to, but it just all depends

CB: Why were air tests conducted, what was the purpose?

FB: When you went on an air test, obviously they would test the engines, so what they used to do, was, switch one off, off at a time and you know, get the reaction of erm, for instance mag drop, things like that. They used to try and test all four, one at a time, and then they would feather them, you know, and of course when you feather them, then of course you un feathered them to start them up again and all that and the old Lanc, that would fly on one engine, but obviously it was forever losing height, but they did these air tests just to see that everything that had been done was working as it should do. I didn’t go on many, but erm

CB: Where would you sit when you went up on an air test?

FB: Well, of course, with the full crew there, you would sit on the floor kind of thing [laughs] that weren’t very comfortable

CB: No, thinking of the

FB: And the poor old, the rear gunner, he was the worse off really because he was so far away from the rest of the crew you see, you’ve got your pilot and then your flight engineer, er, your bomb aimer observer and then of course the wireless operator had got his own little bit and the navigator [pause] [unclear] because er, well it depended on where they were going, but you get eight or nine hours, stuck up in one of those and [pause] no, I don’t think its er [pause] It’s marvellous what they did actually

CB: You said you originally wanted to be flight engineer but once you got on the flight line

FB: I must, I must admit that when I’d done my training and I went out on a and saw what was happening, I thought, well I thank my lucky stars I don’t, of course I was on the volunteer reserves, so if ever they did want a [pause] sort of a flight engineer, I suppose I would have been called up, because the flight engineer, as I say, the flight engineer as far as I can understand, their engine training was similar to what we did as a flight mechanic engines, it was just the extra, erm, you know with the checking the fuel pumps and that, switching the switch in the tanks and er, and I think that they did a little bit of basic flying if the pilot, you know, got injured or killed or anything like that, to take over, and er, but, so no it must have been. You could tell and get quite a good idea of, I mean, no target was easy, I mean there was always a danger there, but you could get a pretty good idea, if they were quite chirpy when they came out it was one of the not so difficult raids they were going on, but if it were Berlin or anything like that or, always they were very quiet which you could understand

CB: Yeh

FB: ‘Cos they not only had to put up with night fighting, there was anti-aircraft guns, must have been horrible

CB: How often did your two planes return with damage?

FB: Er

CB: And what was it?

FB: [pause] Do you know I can’t remember, if they ever did come back with any damage that I worked on [pause] no, I know that was when we were at er, at Wratting Common, about 1944, one night I heard, when, when they started sending these erm, oh, doodlebugs over, but er, they sounded, their engine, it sounded like an old two stroke engine struggling up a hill, [laughs] up a hill, kind of thing, and er, and of course the thing was once the engine cut, they come down, and this particular night, I went to the Nissen huts and there was some windows at the end, but not the end in between sort of thing, and actually saw this old doodlebug going and the engine cut, and it went down and it fell, and it fell just outside of the airfield [laughs] oh dear, it was an experience

CB: What was the most frightening part of your service, which would you say?

FB: Most frightening? [pause] I don’t really know, I do recall one thing that was happening, now when they were winching, winching erm, [unclear] it was a four pounder,

[unknown inaudible]

FB: Four thousand pounder, I think that was when

CB: A cookie

FB: Loading a four thousand pounder up, and it dropped, and we ran, we ran, and then we suddenly realised that if it had gone off, if it had gone off, we wouldn’t have been there, but er, the trouble was with the, if the incendiaries fell, I think they only had to drop about nine inches before they, and they were in long canisters, and there was a sort of bars that when, I suppose, that when the bomb aimer pressed the tip, then I suppose these bars fell away and then they just fell down in a cluster, I don’t know

CB: And er, you saw the, you were there when the crew got in the plane to go

FB: Oh yes

CB: And you were there when they came back, what sort of erm, relationship did you have with your ground crew with them?

FB: Very good, very good, yeh

CB: And so, did they talk to you when they landed?

FB: As I say, they, [unclear] what they, you used to say, ask them if there were any snags, if there were they told you what they were, but erm, they didn’t say, they didn’t say a lot, I mean, they were just waiting for the lorries, or whatever they were using to take them back for debriefing and they would say they were tired and I don’t know what they experienced, you know

CB: Quite

FB: So, but er, other times, I mean, if they, sometimes they would come out, because they weren’t, if I think, I think that what they used to say that happen one day, two raids and then down one, of course they had the leave as well, they didn’t all have the leave at the same time, so they would, they er, say if the erm, pilot was on leave or something, there’d be another pilot take over. Quite often what happened, with a crew, when they come out and then, there was a new crew had been, er, sent to Witchford, the pilot would go as a, I think they call it, a second dicky or something like that, but they used to go out, they were taken out on their first raid

CB: Just the pilot?

FB: To get the idea that and what it was all about

CB: What about the social life on the airfield?

FB: Well, what we used to do if er, [pause] when you, well you see, you used to get up and have your breakfast and then get up back onto the flight, er onto the airfield and do your work, and in the evening you could go to the NAAFI, or down into the village into the pub, which quite often that’s what we did do, and erm, [pause] I can’t remember the other, we had a cinema, I can’t even remember going to the cinema anyway, probably we did, and of course we spent a lot of time in your billet writing letters, you know, home and that kind of thing

CB: Did they run dances?

FB: Erm, [pause] no, not that I’m aware of

CB: Right, so Witchford we’ve talked a lot about, what was the difference, when you went to Wratting Common?

FB: The difference? [emphasis]

CB: Was your accommodation different or the same?

FB: No, no it was still Nissen, still Nissen huts, much about the same as at Witchford, ‘cos erm, 115 of course that was one of the most successful and er, and suffered some of the heaviest losses during the war, but, at Wratting Common, I of course, I was nineteen, 1944, when we moved into, into er, Wratting Common, I can’t remember, I didn’t have all that long at Witchford actually, I’ve forgotten though. It was definitely 1944 when we moved over to Wratting Common anyway

CB: Yes, so, you were at Wratting Common until

FB: The war ended

CB: The war ended, that is to say the war in Europe

FB: Yes

CB: Ended

FB: Yes, yes

CB: Okay, and so

FB: I think we, I think, [pause] I think it was 1946 when we actually disbanded

CB: The squadron disbanded? Yeh

FB: [pause] I’ve got some [background noise] [inaudible]

CB: And so, everybody stayed with the squadron and until the squadron disbanded, is that what you mean?

FB: Yes

CB: Yeh [pause] we are just looking at timings. So, what happened, er, we can look that up later, what happened when they decided to disband? How did that get announced?

FB: Well, as, [laughs] as far as we were concerned, they said we were disbanded and that’s one thing I always regretted because I’d always worked with Malcolm Buckingham and we never exchanged addresses or anything else, meaning we didn’t keep in touch

CB: Did you never?

FB: No

CB: Know what happened to him at all?

FB: No, and when I, when we were on holiday, he came from a little village called Grundisburgh near er, that’s not that far away from Woodbridge, and we went to on holiday to er, Yarmouth or something, well down that way anyway, and I drove round, well, that was us and the two children, I drove round to this little village, and er, I went into the pub and I said does anyone know a gentleman called Malcolm Buckingham, and they said, oh no, never heard of him and that was as near as I got to actually ever finding him. The other one I palled up with, which is on the, on one of those photographs is erm, he was a Scotsman, ‘McKay the Jock McIver,’ and he lived at Thurso, and he used to get an extra days travelling for the distance he had to travel, but if the three of us were off duty at, at you know, we used to go down, generally used to go down the pub and have a pint or two and a sing song and that, ‘cos aircrew used to down in there as well you see. And erm, it was alright in the NAAFI, we used to go, you could go in the NAAFI. If I remember right, sometimes, and I think that was towards the end of the war anyway, if I remember right, they used to have this ‘housey, housey.’ as they used to call it in the old days, bingo, you know and that, but I think mainly we used to just go down the pub and have a pint. [laughs] I was trying to look see [pause]

CB: So, so you had no control over your demob, they just decided when that would be?

FB: Well, you, you had your group you see, I was fifty-five, when I, my group, when I got demobbed

CB: In your grouping, yeh, which was, so you were demobbed on the first of April 1947

B: 1947, yeh

CB: What did you do then?

FB: Well, I came home and erm, you had accrued, erm, what was it? Fifty, I think fifty-six days, fifty-six days leave, er, yeh, and I think owed fifty pounds demob money [pause] it all depends, I think, but erm, fifty-six days leave, I think that was a, er, minimum, I think it probably, if you did more service than that or where ever you’d been, they may, I’m not sure about that, that may possible have been longer, but I think fifty-six was a, sort of a general thing

CB: What did they give you in the way of clothing, when you were demobbed?

FB: Oh yeh, you handed in your suit and you got kitted out with the, well, with shoes, socks, pants, vest, shirt, erm, now I think I’m not sure whether you could have a choice of a suit or these sorts of flannels and a jacket, I can’t remember, what did I have? I know one thing, that when I, when I joined up at Padgate, of course we had to send er, send erm, civilian clothes home, and mine never, mine never ever arrived, they were lost, which I think happened quite often, but er, yeh

CB: So, you got your leave, you come back, then what?

FB: I think I, yeh, I think I had a fourth, two months and then I went back to the United Dairies because they were duty bound, or anyone went back to their old job, or wanted to go back to their old job, I think the companies were duty bound to take them for six months. So, of course, I went back and er, [laughs] Jack Hancock, he said, ‘are you coming back in the garage with me?’ and I said, ‘I’d like to go driving if you’ve got a driving job,’ and that’s what I did. I stayed there until I was thirty four, and that was November nineteen fifty nine, I moved then, the only reason I moved was for more money, and I’d got a brother in law who works at Calvert, and he used to say, ‘you want to get on, you’ll be far better off coming to work for Calvert driving,’ and I said, ‘ah well,’ I said, ‘the problem is you get up on eight wheelers and you’ve [laughs] got to do nights out, and he said, ‘well, that won’t hurt you will it?’ But, anyway, that’s what happens, you started off on the small lorries, on the little old Albion’s

CB: [inaudible]

FB: G wagons, they were about two, what was it? two and a half thousand bricks, and then you went up onto the D, and then a K, then a L, and eventually onto eight wheelers. I had ten years on eight wheelers, I came off, my father in law had, had a stroke and er, and Mum she, she passed away, and he was living with us and, well, they were both living with us for a time, and er, he was getting a bit of a problem at night, they was having a bit of a problem dealing with him in the night, and erm, we’d got the two children of course, so I asked if I could be excused nights out, and they said, no you, that would cause a precedent if we do that, and the only answer to it is if you don’t want to do nights out, is you’ll have to come off eight wheelers, so I said, that’s what I’ll do then, but erm, I went on the stores like, the stores wagon and various jobs around the yard, and erm, when the old chap, when he died, but, see we used to start work at six until half past five, we used to do eleven hours a day, that was Monday to Saturday, and then we went down to five days a week, and erm, and eventually, ‘cos there was no motorways when I started at the Calvert, there, there was that short stretch of M1 that had opened in. I think that was in June nineteen fifty nine, I’m not sure and we never used the M1 anyway, but when they built the M4, and the M5 and the M6, we used all of those, and er, [pause] you had, before, before they were built and opened you had to stop to, wherever you were going, you had to stop on your, the route that you were supposed, for instance, if we were going down to, down into Wales, well, we used to go from Calvert to Oxford, from Oxford we used to go then into Cheltenham, Gloucester, Chepstow and then wherever in Wales it was, of course when they opened the M4, we were able to go from Calvert to Swindon, get on the M4, went down straight there, and so, and of course you used to get, when you were on nights out, you used to get your night out money, well er, when these motorways were opened, what would have been night out journeys, it was still night out journeys as far as the company were concerned, but you could get back almost to, you could get back to Aylesbury or Weston on the Green, depending where, and you could thumb a lift home and get back in the morning or whenever, and you used to get your night out money, well of course the company soon got wise about that, and so what we, there was this particular, this big map put in the driver’s room, and there was Calvert there like that, and then there was a five mile radius, up to hundred miles radius, and so, the farther you went, the more you earned, the more you were paid, and but, a lot of them soon got wise, and they thought if they could get two shorter journeys allocated to them, then they could do two journeys and they’d get twice as much money, you see, but I never bothered, by this time I was about fifty one, fifty two and I said to them, I said, to them one day, I’ve had enough of this cowboy driving and I’m going to find another job. As luck happens, I’m out every night, there was, you were put, the list and where you were going the following day, well, on the Friday, on this particular Friday, there was a notice on the notice board advertising a vacancy for a garage maintenance clerk, and I said to Tom Ridgeway who was the foreman at that time, I said, ‘I’m going to put in for that job Tom,’ ‘well,’ he said, ‘you can put in for it, whether you’ll get it or not I don’t know but you’ll have an interview anyway,’ and anyway I got the job and I went, and went onto the staff and I didn’t earn as much money, er salary weekly, but there were one or two perks and the best one actually, it was a non-contributory pension scheme, so when I, when I finished with them, I came out with a lump sum and a small pension, which I obviously still get, so that did me a lot of good in many ways

CB: But had that pension started when you first joined?

FB: When I first joined you paid in, you had to pay in for a pension

CB: Oh right

FB: You had to pay in for a pension

CB: No, when you became staff

FB: That was sort of one of the perks really, because

CB: Non-contributory, right. So

FB: So, I had, well I had twenty-seven and a half years all told, seventeen as driving you see and ten and a half with the garage maintenance staff

CB: These eight wheelers were difficult to handle without power steering, were they?

FB: Er?

CB: The eight wheelers were difficult to handle without power steering?

FB: Yes, there was no power steering on the ones I drove. I came off the road and they went over to these Volvo’s [unclear] were the ones we, they were good but you had this big old engine by the side of you in the cab you see, and it went thump, thump, thump, thump, thump, but erm, the later ones, by this time I was already off the road, but they, they did have power steering, the old eight wheelers, I used to, I never, I never, really did enjoy going down into Wales especially in the winter time, er, because they were, you know, they were building sort of up on the side of the mountain, I supposed you call it, I don’t know or whatever, but that used to be a job turning round ‘cos what we used to do, you see, you used to go down and the, they’d take, take anywhere they wanted the bricks and you set up and er, with the, before they started with the erm, forklifts and that, er, it was all unloaded or off loaded, and you had seven thousand bricks on an eight wheeler, and so, what they used to call the stick up, which was one, one row in the centre, down, and then over the side, you build it up, and then three [unclear] we used to call them, and so you used to take off half, and then turn round and take the other half off you see, well, when you were on, on the these, it needed a bit of moving, handling [laughs]

CB: I can imagine. Before fork lifts, how did you load, who loaded the trucks in the first place?

FB: Oh, the, they, the night shifts used to do that, they were mainly, mostly they were nearly all Italians, they used to be up at erm, Aylesbury, and then they, they said that er, where the old royal, when you went up to the hill, where the old royal hospital was, the other side of the road there, that was, and they used to say the Itie, erm, Italians, and someone, when I got out of bed they [unclear] can’t hear you [laughs] I don’t know, but yes, and they had a place over, oh, Bedford way, somewhere I think. [pause] It was well organised, it was a, it was a good company to work, they used to, when I came everywhere, they used to say, you keep your nose clean and you’ll be alright [laughs]

CB: Well, the pay was quite good there, wasn’t it?

FB: Oh yeh well, the first erm, when I left the United Dairies, I think I was getting ten pounds a, yeh, ten pounds a week, and the, and the first pay day I had at Calvert, and that wasn’t a full, that wasn’t a full week, and I had erm, fourteen pounds, and as you, and as you worked your way up from the small to the eight wheelers, and course eight wheelers, that was top, top rate of pay, but erm, the last week that I was actually driving, and of course by this time they started this erm, radius miles, that first, that was the last week that I was actually driving, that I earned one hundred pounds for the week, but erm, some of them used to earn that, it all depends, as I say, whatever journey they gave me I did, I didn’t rush around to try and get another journey here and there

CB: Right

FB: What I did was, whatever time it took me I did, and that was it, you know, I said, as I said to my wife, I’ve had enough of this cowboy driving and that would have been used to it

CB: This is London Brick company?

FB: That was London Brick company, but before as you see, they again, that was a well-run company, a well-run company, but when Sir Ronald Stewart retired as chairman, it seemed as it going downhill, I can’t remember who took over from him, but I don’t, and they started with training on all the systems, they had sort of a foreman and, well, had a foreman and a charge hand but then they, then they used to have a manager, and a manager and so on and so forth and all this, and I remember that they, the London Brick company, they put in a bid for it to buy Ibstock, which is Leicestershire, and that was, that was turned down, and not many months later, Hanson, put in a bid for London Brick, and that was turned down, and it was turned down two or three times and they had, they put in another bid and that was the sort of final bid, and there was a deadline when it had only got to be accepted or rejected for good. Now, I don’t know if it was true or not, but there was this er, rumour that went around that 48 hours before the deadline, that Hanson didn’t have enough shares to buy it, but it said, now I don’t know whether it was true or wasn’t true, or not, but they reckoned that one of the directors sold him his shares that gave him enough to get the, to get the owning of, and from then it went downhill, because, although the man’s not alive now, but he was nothing more than an asset stripper. He closed, he closed er, London Brick erm, and New Longville, closed that, at Calvert where they’d started doing this landfill, erm, he retained the, he retained the ground, but he shut, he sold the, and that was two, Shanks and McKeown

CB: The dump, he sold too?

FB: Yeh

CB: Shanks and McKeown

FB: For landfill, for landfill

CB: For landfill, yeh

FB: Yeh, er, then of course, Calvert went, everything [emphasis] is gone, Stewartby which is the main yard, you used to have a stores, where they used to run from the Calvert to Bletchley, well, Newton Longville to take stores or collect stores and that, to Stewartby, that’s gone, apparently Stewartby from what I’ve heard is that erm, the reason why Stewartby closed mainly, was because, like, I mean, always getting complaints, even when I was working, that erm, depending on the wind direction, they get a lot of these erm, fumes and that, even overseas

CB: Yeh, in Scandinavia they were

FB: Scandinavia, yeh

CB: Yeh. When did you retire?

FB: I erm, [pause] nineteen, wait a minute, nineteen eight [pause] I started in fifty nine, so fifty nine, eighty eight, nineteen eighty, nineteen eighty eight, [emphasis] yeh, nineteen eighty eight and when they, when they started erm, closing down, making people redundant and that, well, I had to go to the labour exchange which was in School Lane in Buckingham at that time, I had to report there and that basically was a, they knew, I mean they knew I was, they knew all about it at the labour exchange, but, you had to go, report there to ensure that you, your stamp was made, you know

CB: Yeh

FB: Until you was sixty five, and I went there and wait my turn and they gave you a form and filled it in and said to come back in a fortnight. Well, I went back in a fortnight and they gave me another form and it said, do you want work, have you sort work, what wage do you want, what hours do you want to work? All this and I came home and I said to my wife, I said, ‘I’m going to find myself a little job because,’ I said, I hadn’t received any money in that time, not from there anyway, and so, as luck happens, there was an advert in, about the only time they ever advertised, a little firm, erm, Greens at Wicking, and they made these sort of these wooden er, light fittings

CB: Oh yeh

FB: Clusters and clock cases and things like that, and they were advertising in the advertiser on that Friday, and er, I phoned up and I said, ‘it seems like you want some labour,’ ‘oh yes, can you come over and have a chat?’ and er, so I arranged to go at two o’clock on that Friday, same Friday afternoon, well I got over there, funny enough, one of the, one of the sons, I didn’t tie it up but, I played cricket for, and I was secretary of the club for Thornborough for eighteen years, and Brian Green, he had just started playing cricket, more or less as I was coming towards the end of my cricket career, so, when I got over there, I saw, I went to the office and saw Sally, as it turned out, and she said, ‘oh, I’ll go and find,’ and she found Michael, well, Michael and Tony they were twins, and they were identical twins, but Tony he didn’t, he didn’t work there, he used to go over occasionally, he’d got his own business or something, anyway I went there and he took me into the, into the factory and erm, and they’d got these machines, you know, for cutting up wood and all the rest of it, and I wasn’t very, I wasn’t very impressed with it, not really, and Michael said to me, ‘let’s go over in the office then,’ and over in the office he said, ‘what do you think?’ and I said, ‘no, I don’t think that’s for me, thank you,’ he said, ‘we’ve got a little seven hundred weight van,’ and he said, ‘ we’re looking for someone, we keep getting these youngsters that come in to drive and we can’t trust them, they don’t know whether they’re coming or going, erm, would you consider that?’ and I said, ‘well, I don’t know.’ Anyway, I took it on and they’d got these outworkers, so I used to take stuff out and deliver it and the following day, used to pick it up and take some more out and that kind of thing, and then I used to have to deliver when they sold stuff, I used to, I used to go down to, well I used to go down in Essex quite a few times, Yorkshire, Birmingham, I used to go there Birmingham quite regularly and get stuff, and take it and so it all worked out very well and I, and I got to, by this time, I had my, I was due to have my holidays and I was seventy, and er, now Laura Ashley was one of their main customers and they were also one of the their best, because they were always sure of getting their cheque monthly, where as some of the others, they had to wait for the money, you see, anyway, [laughs] so I went on holiday, and Michael phoned me up on the Sunday that I was due to start back to work on the Monday, and he said, ‘Sid, we’re short of work,’ it was sort of a [unclear] seasonal sort of thing, now I’d been working flat out from about September right round to the May, June time, and then it used to slack off again, and then it used to build up again, in sort of like, Christmas trade they used to call it, so anyway I was due to start back on the Monday, Michael phoned me up on the Sunday afternoon, he said, ‘Sid, we’re short of work,’ he said, ‘we haven’t got much for you,’ but, he said, ‘we’ll give you a ring when we get, you know, when we have got some work,’ and so I thought, that’s a good opportunity to go, quite a lot of work I wanted to get done around here, and I’d got the allotment and all, and all the rest of it, and so I said to Bet, ‘I think, er, I think that, I’ll call it a day,’ so I wrote to them and said that I’d thought I’d put it in writing, and I wrote and said that I’d decided that I’d retire, I was seventy and thanked them for, you know, the work and all the rest of it, and two or three days later, Brian, Brian rang and he said, ‘you sure you’re not going to come back?’ and I said, ‘yes, I’ve decided to pack up,’ he said, ‘we’ve got plenty of work for you now , we’re expecting you back,’ but I didn’t go back

CB: You’d had enough

FB: I’d had enough, I was seventy

CB: Yeh

FB: And I thought, well that’s it

CB: How long have you lived here?

FB: Since the bungalow was built in nineteen seventy-eight

CB: Oh, have you really, yeh

FB: It’s a, these six bungalows, three either side and they actually they are council, er, let for senior citizens or old age pensioners, whatever you call it, and we were living in a four bedroomed house, number twelve up the road, and by this time, Dad had died, my mother and father in law had died, Geoff had, Geoff had gone to Imperial College, London, in the university, and Jill, she was going to Loughborough, and there was us two living in a four bedroomed house, so I wrote to the council and I said, would it be possible to, possible to rehouse us in a smaller, either a two bedroom or possibly a three bedroom house, and what I got back was a letter saying that they weren’t selling bungalows and they weren’t selling four bedroom houses, well [laughs] I didn’t want either, but anyway, they started building these bungalows and my pal who was on the council, he said, ‘I know you want to move, why don’t you put in for one of these bungalows because they said, five of them have gone, but there’s six and they’re supposed to be for local people you see,’ he said, ‘five of them have gone, but there’s one that’s still open, why don’t you apply for it?’ and I did and originally they said I wasn’t old enough, but in the end they did sell it, er, did let it to us, and when the right to buy came, I applied to buy it

CB: Because you’d got the continuity

FB: So, we bought it and that’s it

CB: Yes, that’s good

EB: You alright?

CB: We’re having a rest now, thank you

[interview paused]

FB: The most memorable time?

CB: Your most memorable time, memorable time, in the RAF would you say?

FB: [pause] [laughs] Well, I don’t know [pause] I should possibly think was when that aircrew completed their thirty ops, because that was, when I first got on 115 Squadron, if they managed to do seven, they were doing very well, so I think possibly that would be one of the stand out things that, I mean that. I can’t remember anybody else, not while I was there

CB: So, you were looking after two aircraft, one did thirty but you had a series of others, as the other aircraft

FB: Well, yeh, because, in actual fact, if you [background noise] [pause] that would, that was D-Dog, that was one of the, that was the one that Malcolm Buckingham and I worked on

CB: Yeh, that

FB: And that’s the one that did, the crew did their thirty ops on

CB: Yes

FB: Er, and that went on as I say, to do hundred and five, but er, by the time we left, it had done, I think it was sixty ops, and the rest of them of course, it was done after we left

CB: ‘Cos you got another crew, after thirty?

FB: Yeh

CB: After thirty, thank you, brilliant

FB: This one, that’s up there, that

CB: Your pictures on the wall

FN: That’s, that’s C-Charlie

CB: Yes

FB: C-Charlie, er and they were the two planes, you know, on the two pans as I was explaining. I don’t know how many operations that done, but that down there, what was it? Five, ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, that done thirty, by that time [pause] [background noise]

CB: [inaudible]

EB: 1947

CB: Now, in the war, when you were in the RAF, did you ever have any serious illness and what was it?

FB: I had, I had pneumonia while I was in, at Witchford, I spent er, what did I, a few weeks in Ely, Ely hospital, and I was excused oversea duties for six months, ‘cos I didn’t go overseas anyway, but I was, and the other thing was that, yes, on January the 25th 1947, I had, I’d had an invitation to go to Bet’s sister Margaret’s wedding

EB: Why she wanted to get married

FB: And, I, and I at that point, I was a senior fitter on our flight and I couldn’t get a weekend pass, which as it turned out was just as well, because on the Saturday afternoon, I was sat on top of an old Wellington, doing a plug change [laughs] and I curled up, there was a young national service chap on the other one, I forget his Christian name, but Gaskins he was, a Londoner, and I said to him, we’ll go, we’ll go down into Lincoln and have a little bit of a celebration, [laughs] being as I can’t go over to this wedding. I slid down the main as I, slid down the main frame and as I straightened up, I had this pain across, and the sergeant he said

CB: Across your stomach

FB: Yeh

CB: Yeh

FB: He said, ‘what’s the matter with you?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, I’ve got the cramp or something, I think?’ he said, ‘go on in the hut and stay there until we knock off and go down to tea,’ which is what I did do, and I said to old erm, Gaskins, I gave him my mug and I said, ‘get me a mug of tea, I’m going to get into bed,’ so I went to my hut and lay, and got into bed and he bought me this mug of tea, and I hadn’t got it down many minutes before I felt sick, and I shot out of there and ran into the ablutions and I heaved up, and I kept on, and went back into there every now and again, and kept repeating, repeating all the time, and he says, ‘well we shan’t be going down for a drink tonight, I’ll go across the sick bay and get the orderly to come and see you,’ and he did do, and the orderly said, ‘oh I’d better get the MO,’ he [laughs] tannoyed for the medical officer and they took me over to the sick bay, and he said, ‘oh you’ve got appendicitis,’ so they took me off to [unclear] hospital, and it was snowing, it started snowing you see, it started snowing , anyway, and I got to [unclear] anyway they operated on me and I’ve got an awful scar here, where I had a stitch abscess, and they sent me home er, on, I had a fortnights sick leave but I had to get into Buckingham every, every day to have this dressing changed, that was a bit of a problem, but er, but also, [laughs] when I was discharged to come home, I got down to Bletchley, station, railway station you see, and the old porter he said, ‘no trains to Buckingham until tomorrow morning,’ I said, ‘I know, I know that,’ I said, I’m going to,’ ‘well,’ he said, I don’t know whether you’ll have any luck because,’ he says, ‘we’ve heard that the road is blocked, somewhere along that road,’ and I said, ‘well, the army,’ of course there’s Bletchley Park, that we didn’t know anything about, but there was Bletchley Park, well, they were running from there to Whaddon and also to Lenborough

CB: What, the army trucks?

FB: Yeh, well, with the signals, you see, you know, and they would always stop and pick you up if you wanted it, you know, wanted a lift, and there was just one went past me, and that was before I got anywhere near to the Whaddon turn, and he went straight past me, and I never saw anything else, [background noise] and I walked and from Bletchley, what is it, to Thornborough, it’s about eight miles, I think it is about eight miles, something like that, but when I got round to Singleborough turn, the straight bit there, I could see this shape in the road and it turned out, it was one of the Coop tankers in there, and of course the, where Bet lived at Greatmore it, you needn’t open the gate, you walked straight over ‘cos it was about five foot deep, you see, it was, anyway I got back in, I got back home, I think it was about two or three o’clock in the morning, something like that, and rattled the door and my Dad came [laughs] ‘cor, he said, what’s happened to you?’ I said, ‘well, I’ve walked from Bletchley,’ and so, got into bed, and as I say, every day I had to go into, to have this dressing changed

EB: He walked four miles

CB: Can’t have done him any good to do that?

EB: No

CB: Because this, 1947 was one of the worst winters

FB: It was

CB: In living memory, wasn’t it?

EB: [inaudible]

FB: Well, there was still snow under the hedges in May

CB: Was it, in Rutland we couldn’t get out of the village for seven days

EB: Oh gosh

CB: Amazing

EB: Where was that?

CB: That was in Empingham