Interview with Jan Black. Two

Title

Interview with Jan Black. Two

Description

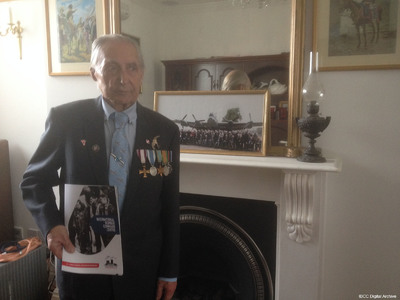

Jan Black Stangryciuk was born in Poland but his family emigrated to Argentina in 1934. He volunteered to travel to England to join the Royal Air Force in 1939. He recounts his journey, why he made this decision and how he joined the RAF. He was involved in a crash landing during training in a Wellington in which he sustained serious burn injuries and he describes this event in detail and his subsequent hospital stays and treatment. After recovery he spent time as an instructor at gunnery school at RAF Evanton before rejoining his squadron. He undertook a total of eighteen operations in Lancasters with 300 Squadron. He eventually left the RAF in 1948 and married his wife, Evelyn, and he explains why he took on her surname.

Creator

Date

2017-03-14

Coverage

Language

Type

Format

02:08:10 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

AStangryciukBlackJ170314

PStangryciukBlackJ1701

Transcription

CB: My name is Chris Brockbank and today is the 14th of March 2017 and I’m in London with Jan Black, who came from Poland originally and we’re going to ask him what, what about, what he did in his life. What are the earliest recollections of life that you have Jan?

JB: In Poland?

CB: Yes.

JB: Yes, I was, my people were farmers in Poland and of course I was going to school and helping, you know, my parents you see. Agriculture worked in. Yes. And then when my family decided to emigrate to Argentine and in 1934 we had all the docs, immigration documentation complete we went by sea to Argentine and we dock in Buenos Aires. That’s the capital city of Argentine. Then after, after [pause] seeing different part of Argentine my family settled in province named Misiones. That was big province near Brazil, Brazilian boarder. Then, then I starts school in Argentine to learn Spanish and to uplift my further education. Then after living four years in Argentine the war broke out in Poland and my country was invaded by the Germans in September 1939 and after ten days the Russians attacked my country from the east. To me it was very sad time hearing all the news and destruction what my people start to suffer under the German and the Russian occupation. And every day I was reading in the newspaper how continuously different, different system was in force on my people and I start to feel very sad for my country. Then after about three months, in the Polish newspaper printed in Argentine, there was very happy news I receive. What the Polish people and the ordination could volunteer to come to England and to join armed forces and to fight against the Germans. I went from my homeland in Argentine to capital city Buenos Aires to the centre, where we had to report our intentions of joining as volunteers and to come to England. When I arrive at that centre we’d been check by medical board and we had tell them why we decide such a decision to come. And it was very straight forward answer, what we just wanted to go and fight against aggressive occupation of unfriendly nation. After having medical check up, we’d been asked when we would like to go to England. I told them soon as possible and the person who was in charge at that time told me what they will check my health and if I want to go soon they will notify me in two weeks, and they told me I can go home and wait for the next information. After two weeks I receive letter and a ticket, railway ticket that I can come to certain centre in Buenos Aires, the capital city, and I would be accommodated in one hotel. When I, on the second day, came to the meeting place I notice that there were different nationality volunteers. Polish, English, French and I was very happy what different nations also were coming as a volunteers. We’d been told in that hotel what we must keep our secret about our destination because there was lot of Germans espionage during that time circling in that part of the city. We’d been told what our departure will be very short notice given and be prepared on such an event. Then one evening notice was given to us at six o’clock and we’d been told what we will get transport to board on the big British liner from Buenos Aires port, when the big boat will take us to England. The name of that boat, I remember, it was the name Highland Monarch belonging to the British Royal Mail Line. That company had four big liners continuously travelling between England and Argentine and they, what they, during that travelling between England and Argentine there were, they were bringing lots of meat from Argentine to England. I say food for the war days during the difficult times. When we started our journey at night, at twelve o’clock, very secretly we had been told what we must be very alert because our journey will be continuously in danger from the German submarine or big German battleship which are circling on the Atlantic Ocean. We’d been told to be always , have ready, wear jackets in case the boats get sunk, we will have life jacket attached and the boat was continuously during the journey not going on a straight course only circling, zigzagging to avoid be spotted and sank by the German submarine. The journey starting from Buenos Aires to England took, instead of three weeks, took four weeks because the boat was zigzagging and loosing lots of shorter distance between England and South America. When we came closer to England we’d been told what our boat would dock in Belfast, Northern Ireland because to come closer would be much more danger as during that time the Germans continuously kept bombing our port on west from western approach. When our boat disembarked us we’d been taken to the local hotel for a couple of days and then we were taken to Scotland to some military barracks centre. And then again we had to pass the second medical board from the doctors. Doctors during our medication and inspection bought us, ask us what armed forces we would you like join. We had choice to serve in the Royal Navy, Army, Air Force or other forces. I was young and I thought the most exciting service would be Air Force. The doctors told me what my medical board said it was good enough and I, if I want to serve in the Royal Air Force I can make already decision what I will be, will be accepted. Then we’d been accommodated in some army barracks in Scotland and start telling us what now we will be sent to different centre when we start to continue our trainings. My selection was decided to send me to Blackpool where was Polish RAF centre for beginning my training to start learn of my future responsibility. After studying such trainings for months will be taken to special RAF centre. The centre it was 18 OTU Bramcote. When we start to continues the next training with flying. That training was very exciting for young men like myself, but it was very speedy training. We had not too much time to have, for other exciting moments. Training was long hours of different responsibility to get us ready, equip for responsibility we would be facing for our future flying. I was happy to start my training flying on Wellingtons to wing engine bomber at that time and I knew that soon I will be selected to the operational squadrons, but during that time we had to go on evening [unclear] training. During take-off my Wellington had fault in one engine during take-off. We crash during that take-off and I lost consciousness during the impact of our crash. When I recover my memory I could see what part of my plane was in flames. I start walk to the front of my plane and see what happening to the rest of my friends. When I reach the position where my pilot was sitting I saw him in his special seat. I did try to get him out of the burning plane but he was still strapped in his seat and during that time the plane was quickly increase in the bigger burning flames. I knew and I could see how to un-strap him from his seat and I cover my left side of my face because the flames were obstructing and burning my visibility and helping myself with the right of my hand looking for exit from the burning plane. Luckily at moving inside in that burning plane, I was lucky to see what my plane during the impact had crack in its construction and there was broken exit from that plane what I was lucky to squeeze myself from the small hole of my burning plane, but I already couldn’t see normal because my eyes were already damaged from very strong flame was burning round the plane. I start to crawl a certain distance from my plane and the local people found us. Came to my rescue and they torn my burning combination suit because without that help I would be completely burned to die. I was so lucky what those people were so brave and came so close to that burning plane and they took me inside into their local house but I couldn’t see nothing because my visible, visibility was damaged. But they told me that they had already telephoned for ambulance to come. In about half an hour ambulance came and they took me gently into RAF Hospital Cosford near Wolverhampton. I was in terrific pain. I was so happy to be dead at that time because it was such a painful experience what I had to go in my lifetime. But the doctors soon came to my rescue. They told me don’t worry your pain soon will stop. I didn’t believe them but they had the answer to it. They give me certain tablets and I think some injection to stop my pain. When I recover my memory, I think it was the next day, I could not see nothing because my eyes were damaged but the doctor came and talked to me and told me that I will be making progress with their help. I thanked them very much but the most biggest thing I receive from them was my pain was already under control. Then my small recovery started day by day. [clock chiming] The nurses every day would take me to the bathroom, put me into the bath and gently try to remove my bandage that I was strapped on my head and on my hands. That bandage was soaked with a special oil so that oil prevent so the bandage doesn’t get stuck to my burning flesh and they gently will remove that bandage every day and cover me with the fresh new bandage. After having the same routine day after day, after two days I been told that a very special doctor will come to see me. The name of that doctor was Sir Archibald McIndoe. He was one of the biggest plastic surgeon doctor in the Royal Air Force Hospital, Queen Victoria in East Grinstead. He came that hospital to RAF hospital in Cosford and to see certain airmen from different accidents. When he came to see me he told me his name and he told me he would like to transfer me to his hospital in East Grinstead and ask me if I will be happy to go to that hospital. I turned to him and I said to him ‘doctor I leave all the decision to you because you know the best about my problem and what to do with me’. He was happy to hear that my great thanks to him that he wanted to take me to that special hospital in East Grinstead. The next day ambulance took me to that hospital. When I arrive in that hospital I’d been told there are so many boys from different accidents and different nationalities. There were English, Canadians, Polish and I think some French. I was so happy to be in such a friendly hospital. Queen Victoria Hospital it was one of the most famous hospital in the world for the badly burned, disfigured young airmen and the city, small town East Grinstead. It was our, the most lovely place maybe in England because those people understood and feel our disfigurement and they never stare at us in such bad disfigurement as we receive from different accidents. East Grinstead give us hope to continue, having such a big hospital with such advanced capability to improve our standard from the most horrible disfigurement what the fire could give to you. Must stop now.

CB: Right.

JB: How we play this, you know broken mentally now. You know what I mean?

CB: Yeah, they knew how you felt.

JB: Yes you see because you come to London people don’t, when they see you in certain still disfigurement they think, think probably you come from other planet or something. [laughs]

CB: [laughs] Yes, yes. Can I just ask you one thing and that is what happened to the rest of the crew because there were five of you on the aircraft or six?

JB: Yes. There were, I was one and the rest died. I was the only one that survived. Yes.

CB: Yes. Right. So you were flying as the co-pilot?

JB: Um.

CB: You were flying as the co-pilot?

JB: No. I rear gunner.

CB: Oh, gunner?

JB: I was the rear gunner.

CB: Oh, right.

JB: Yes, yes.

CB: OK.

JB: I did try to save my pilot because, but by the time I tried to reach the plane was in flaming.

CB: Yes.

JB: In bigger. So I covered my left side and tried with right hand so I burned my right side you see. Because you can see it you see you lost your visibility and the way to find the way you just had to with one hand. Even in your hand you was using feeling because hands was burnt. Fire you see. The biggest enemy what you could face.

CB: Absolutely. Yeah.

JB: Because I was — three times I see young boy drowning I say but you can fight drowning, but fire —

CB: Fire you can’t.

JB: It puts you out of completely, out of control you see. Fire the biggest enemy what you could face.

CB: Dreadful. Yes. So how soon after take-off did the engine fail?

JB: You see, what I want to, ‘cause I asked for break.

CB: Yeah.

JB: Then after spent six months in hospital. Hospital was getting so overloaded with new cases coming night after night and they were running short of beds, so what they used to do they sent you back to your stations for certain time.

CB: Right.

JB: And they patched me up. The beginning of my recovering and I’d been told what they cannot do another operation because I must have certain recovery time you see.

CB: Right.

JB: And they got in touch with my station but I would be discharged from hospital for short time and my station send me railway ticket from East Grinstead to Scotland, to Evanton near Inverness to gunnery school. And in that place there was, they give me instead of having a bit more recovery I had to continue flying with the new course, batch of gunners who come. Flying Boulton and Lysanders so the new gunners always be — I already was advanced as a gunner and give them instruction how they have to continue the more — the rest of their training. How to shoot the Lysander whose pulling behind him they sat and they firing from the Boulton twin engine plane with the [unclear] turret. Yes. To teach them how they have to see the distance. When the Lysander approaching them and they will be able to know the distance from what distance they can open fire, shooting to the Lysander sat which is dragging behind. And sometime it was very, very danger, you know, because the new gunners they had no hundred percent control of what they were doing. Sometimes they turn bit too much quickly and they shooting instead of sat and they shooting closer with the pilot you know flying Lysander. [laughs] So the pilot talk to me on the intercom ‘what’s happening? Can’t you see what’s happening?’ I said ‘yes skipper, I see what’s happening’. You know, I said, you know that’s not going to happen again. So I run to that gunner and I say he must move the turret gently not you see, but they kept not feeling it yet. So I continue that training for three months in Scotland. Evanton near Inverness. And after three months, after three months I went to my commanding officer and I said to him I said ‘Sir, I would like very much asking you for one favour. If you could give me permission to be sent to my squadron.’ And the commanding officer in the gunnery school asked me why I want to be transferred. I ask him after having three months responsible job what I was doing I found I just cannot continue, you know, to do that. He said ‘you will do that’ but he said I must wait another few days. I thank him. After, I think four days, I had my railway ticket with the rest of my documents, discharge from that station gunnery school to my squadron. When I arrive to my squadron, the next day I had to report to the commanding officer. My commanding officer ask me why I asked to be transferred to that station. I told him what I spent three months as instructor in that gunnery school and it was just too much to continue and he ask me what I want to do on my station. I turned to him and I said ‘Sir, what I want to do, I want to do same thing what I been taught told what to do. I been teach to fly and do my flying job.’ He said to me will I be, if I will be able to do that. I said to him I think if I did already three months as instructor in the gunnery school, I am sure I will be able to continue to do the rest of my job. He said alright but, but they still send me, he send me with two doctors for two hour flying and the doctors kept talking to me during those two hour flying, looking at my reaction and my, and my [pause] and my, how I feel if I’m not nervous or something or they could notice, not capable to continue to do my job as I ask my commanding officer that I wanted to fly again. After two days my commanding officer saw me and told me what the doctors give him result without no problem so I can continue to do my flying again. I restart doing my operational flying and at one time I receive letter from hospital and hospital ask me to go back for the continuation of the rest of my treatment recovery. I took the letter and gone to my commanding officer and show him the letter and commanding officer turn to me and said you should be very happy what the hospital want to continue to improve you, the rest of, give you treatment. He said you should be only too happy to that hospital and he said I must go. On the third night after departing from my station and departing from crews what I was flying with them. On the third night they went on the night mission and never return. So you know my history, twice luckily, you know had enough luck probably you know not to end up with the rest of my friends, you see. By the time they finish my, the rest of my treatment the war was over, but I still serve ,still serve three year longer, longer. You know, because I was young and they were discharging mostly older people. And in 1948 I had my discharge from Dunholme Lodge, the discharging station, Dunholme Lodge in Lincolnshire. Yes. And that’s when I started to go into the civil life. Then I got married to my wife. That’s why because I didn’t marry her during the war because I told her the war brings so many unexpected changes but when war ended we, we give each other promise so we get married. And we kept to our promise [pause] after living with my wife for fifty-two years [pause] I promise her what I will never leave her. So when I die I give her promise I will be buried with her together and that’s what I will give, going so you see I thought England is my country, my history here. They called me when it’s Remembrance Day [unclear] London Royal British Legion I felt if I go back to Argentine, I took my wife to Argentine I ask her if she like to see my family and we went by boat because during that time, after the war it was not such a long distance plane flying, so we went by boat. Three weeks going there and three weeks going back. But Argentine was changing after the war, different Government, different changes and I thought I was already more adjusted to life with my future wife in England. We returned and restarted our civil life and now I go to Poland for short holiday. I got some time to Argentine now, it’s easier to get there but I thought I came to England when time was difficult and we achieve our aim and this country had guts to stand up, you see and to [unclear] enough was enough without England the world would be different today. So that’s what I did for this country. There was nobody else could stood up. The English had guts to do it and the rest of people would join.

CB: Um.

JB: And without such a decision probably, you know, I don’t maybe for a thousand year the world would be different.

CB: Um.

JB: But you see the people, young generation don’t know what took [unclear] you see I saw in my squadron when sometime you come back and that table it was empty in the dining room and you thought sometimes think to yourself when my table will be empty. Because we could always eat together. We be like brothers if you know what I mean. And we — whatever happened after the war we made Europe different for so many years.

CB: Um.

JB: The people parted in different parts of the world now making destruction and so on but we show the world what Europe will change and I think this whatever we make changes we should be happy that so many people give their lives in the second war. But we must always remember that we don’t want to go back to the old days what Europe was, you see.

CB: Um.

JB: And we, we had our — the one thing after the war I was really heartbroken when Mr Churchill was not elected as our leader because I thought in the most difficult time when he took over, er, we should have given him that big recognition what he started in difficult time and achieve with the rest of the people in the world such a great victory and recognition and using the election, you see because I think that was the biggest mistake what we make after the war. Because with him I think we probably would be still much better off, you know what I mean, because that meant was seen all over the world you see.

CB: Um.

JB: But sometime politician do make mistakes too, you know what I mean. Men go, will fight and do his job and the politician make mistake too, you see. But that’s how things go, you see. To us and it will be continue.

CB: Um.

JB: And I mean I have sister in Argentine. She’s younger than me, a few years, and she said to me why don’t I go back and live with, with her and her children. I said no, I said I came during the war, I was a young man, I found my girlfriend here during the war and I said I would be feeling lost there, you see. Because I said, I in this country have some recognition you know. What I did, I mean if I would go to other country, even in Poland it wouldn’t be the same like here.

CB: Um.

JB: You see I belong to the Guinea Pig Club. Duke of Edinburgh [unclear]. He’s our president of our Guinea Pig Club, you see. He used to come sometime if he was not abroad to our dinner in East Grinstead. I had couple of times chance to talk with him, you see and that give you something what you, you used to have special days, Remembrance Days. Royal British Legion give me invitation to all the smaller things and you, you just feel you don’t want to lose that recognition, you know what I mean.

CB: Um,

JB: I will not receive that in another country. Yeah. And that myself what I as a young man came from the Atlantic all ready because I was feeling hurt what my people suffer of two unfriendly nation. Russia and Germany and I thought it was all wrong what we in Europe in those days for so long had so many times, you know, continuously such an unfriendly living. Yes. And now whatever look, year seventy over seventy years people travel you saw no fighting we give the rest of the world example what they should take same thing what we did. You know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: But we don’t know how long it going to last because you see because there new super power emerging with nasty ideas. Yes. And that’s why those [unclear] sooner or later will be happening all over the world. There’s nothing worse when dictator get power, you see, because they don’t listen to nobody. I mean those big dictators, you see when they done, have democratic system they take power into their hands and that’s what always was not much future during. Luckily we got rid of them [laughs] but some as soon you got rid of them then some new emerging [laughs] yeah. But, we took, when we took that big decision in 1939 and Mr Chamberlain used to, Neville Chamberlain used to go to Hitler and ask him what you, why you continuously want more, you already took so many. And he used to always promise the British Prime Minister there would be no war you know. But the rest of the world knew that the Germans was arming themselves and preparing themselves for the big expansion of their empire. You see that’s why [unclear] Germans because they wanted they could get pressurising Poland what Poland should give them [pause] chance to march, attack Russia because they knew that Russia was such a huge big country. And they knew it would be easy to, in those days, to overpower that part of the Eastern Europe. And Poland they wanted no German friendship nor Russian. They used to live between two very unfriendly neighbours you see. And that’s what happened, you see. And Hitler, you see, in the end took power into his own hand and he was gaining without fighting from beginning. Yes. And if in those days there would be no England there was no other country who would be stopping his expansion here because he already had everything going easy, easy. And even after when France collapse, look he was almost big military hardware which he recover from the French. I mean he used to make himself from strength to strength you know, without. He’d overpowered Czechoslovakia, took very big modern small industry, Skoda. Took the French, you see, military hardware and he was gaining from strength to strength he was building himself. It’s a good job there was one country still standing in the world. What they knew they cannot give in no more and they told, told on the last many meetings of Mr Chamberlain had what if, if he continue with Poland because Poland had treaty with England and France at that time. What the world will be unavoidable. But even so he took so many chances and he gained without problem and he thought it would continue but he made mistake you see. But the British decided they were going to stand up to it. Yes. But you think, you think there is the world that’s why in Europe now you see we, we should have much bigger recognition, you know what I mean in, in that. There’s twenty-seven countries, yes but we should be classified you know exactly as equally you know because there is difference between one country and another, you see. And the trouble was immigration was big problem for long time, you see, because now they well staffed to notice that what you know we must do something and cooperate not listening just to one country, you see, because it is a world problem you see and, but Europe didn’t listen much you see and that’s probably what ever happening changes or we don’t know how it’s going to end, you know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: But it was problem because they used to come to [unclear] and not the one country was selected the most of them wanted us England, you know what I mean, because it was the most place where they could get the easier living and you see Europe then should talk it out more into consideration what they should cooperate together. I mean the Syrian problem started, Europe start to wake up you know and notice the big problem to the rest of the world but there is not only secondary there is African problem yes coming. And Europe must work together to stop that because one country cannot do it. Now, now after all these years [unclear] tried to clean it you know what I mean. For how many years and it was spreading because during that time lots of people were making money out of it you know. Everybody had fingers in it, you know what I mean.

CB: Um. Um.

JB: You see the French were very, I would say, to, to have less responsibility because they, they had their country and they should probably knew what lots of people who come from different parts through their land come to the English Channel and heading, you know to England.

CB: Um.

JB: And for so long it was continue you see, but the, like, you see, in the many, many different ways I think the France took big res — less responsibility they, they start to feel under own problem you see and that’s what happening but probably that should been stopped long time ago, years. But politicians have time to make mistakes you see. And that’s we probably don’t know how going to end you see.

CB: Let’s just stop there for a mo. Now you mention that you had a girlfriend in the war called Evelyn.

JB: Yes, yes.

CB: And where did you meet her?

JB: Yes.

CB: And what was she doing?

JB: I, I met her during the war one day at the Hammersmith [unclear] at a dance [laughs] yes. Yes.

CB: So how did that come about?

JB: Er, well you see Hammersmith was very popular part of London where was lots of during the war activities and there was very famous for dancing you know [unclear] dance and I met my wife but she, she was, er, coming from the Derbyshire, Matlock in Derbyshire. Yes. And my wife during that time was working in cafe royal syndicate. Yes. And I ask her why she’s not going back to Derbyshire and she told me because she come from big farm in Derbyshire but her father send her to London to finish her economy programme. When she receive her degree in the economy she decided that she find better reward living and working in London. And she decided to stay in London and when I met her during my first meeting I ask her why London is her select place. She told me because working on the big farm was very responsible and heavy daily responsible life but she was always happy to tell me what the Derbyshire will always be her, the most lovely part of the country. But one time I ask her why and she told me if I ever heard the name Rolls, Rolls Royce I say yes that’s one of the famous place where they produce the biggest engine for the planes she told me because the most famous people live in Derbyshire and I always will remember her sorts of proud to come from that part of the world. She was very understanding person and I promise with her what when war ended and we survive during the war, if she decide to marry me I will give her promise I will do that. War ended and we kept to our promise. And I will remember what we kept that till the very end. She was very good wife and my memory will be continuous of my happiness what I spent with her for so many years after the war. Yes.

CB: When did she die?

JB: Um.

CB: When did she die?

JB: Oh, eight years ago.

CB: Right.

JB: I bury her in Gunnersbury cemetery.

CB: Oh Gunnersbury. Right. Right.

JB: Yes. Yes.

CB: And it’s big enough for both of you?

JB: Yes.

CB: Let’s have a break there for a moment.

JB: Yes. But we knew the second war was brewing, from, you know, year two year we knew.

CB: Right.

JB: And the, the one thing, you see, what I remember it was what certain dictators were feeling what they could make such a, a big, er, names for themselves, you see, and I think what the Europe at that time was thinking after the first war that they had enough seen suffering that the peace will continue but at that time certain dictators emerge into the big popularity and that’s why Europe became such an unfriendly part of the world. Yes. And that’s what happened. It started from small conflict, it went to the bigger one. And I ask, I took small part in that conflict. I think what we, at that time, played very important part and commitment that we took to not to keep continue making same mistakes in Europe again.

CB: Um.

JB: And I hope the young generation should remember the history what we went through and should not forget that the history should not be repeating itself again.

CB: Um.

JB: We, they have a, have a responsibility for such a big commitments what was started on, we gain our aim in the end and I’m so happy what Europe now is. Whatever is prosperous part of the world.

CB: Um.

JB: Yes.

CB: What was it that prompted your father to leave in nineteen — what was it that prompted your father to leave in nineteen forty, thirty-four why did he go to Argentina?

JB: Oh yes. Because you see Europe was my country, living was hard after the first war and my father look like millions of other European nations, were looking for better prospect in different parts of the world. South America it was huge big empty new land. Lots of people were hoping that they make easier life there.

CB: Um.

JB: You see. He went there, bought lots of land cheaply, because land was cheap there you see. But it’s no good having lots of land if you have no strength to give — aid you.

CB: Um.

JB: To cultivate that is huge responsibility and I, I had feeling what my country was suffering when war started and I, my only happiness was to have opportunity during that time to come to England.

CB: No.

JB: And to fight together with British so my people not again go under for many years of occupation of the very unfriendly neighbours like Russia and Germany. And that’s as I mention in the past what England for many nation give that courage and strength what we together.

CB: Um.

JB: Join in and with such a difficult uncertain future but in the end the things start to show us what we gain our victory in the end.

CB: Um.

JB: And I feel what we must remember the history and the history must never repeat mistakes in the past. Yes.

CB: You’ve also got the British Legion VE70 badge.

JB: Oh yes, I —

CB: So that’s because you were remembering the end of the war.

JB: Yes, yes and I have one unforgotten association here.

CB: Yes.

JB: You know, Buckingham Palace. This one.

CB: That one. Yes.

JB: You see, yes, that’s once, once in lifetime they probably when they think you did something you know so they ask you, Christmas little party you see in the news Buckingham news party.

CB: Um. Yes.

JB: Yes. So you see that’s why for Buckingham Association.

CB: And what is your tie?

JB: Um.

CB: What’s the tie that you have got on?

JB: Tie. Lancaster, yeah that’s my — you see, that’s [unclear] [laughs]

CB: [laughs] Right just going to stop for a mo.

JB: But you see afterwards when I did in my squadron after hospital.

CB: Yes

JB: After gunnery school.

CB: Yes.

JB: I used to do spare.

CB: Yeah.

JB: Because you see in the squadron on Lancaster is three gunners

CB: Yes.

JB: Rear gunner, middle gunner and front gunner and sometime crew, one, one person will have [unclear] operation or something so in the squadron is always spares.

CB: Yes.

JB: Crew.

CB: Yeah.

JB: Person who finish [unclear] and he doesn’t want to be posted somewhere else.

CB: Right,

JB: And he will have a holiday after you do thirty-three trips.

CB: Yes.

JB: Because when you do thirty-three trips you don’t need to fly no more.

CB: Right. Right.

JB: But you just get into it you don’t want to be somewhere, sent somewhere you want to stay in your squadron.

CB: Can I go back to the crash?

JB: Yes.

CB: So you were the only survivor, you were really badly injured obviously with fire.

JB: Yeah.

CB: But how did you feel emotionally about the fact that you were the only survivor?

JB: Oh, well you see that’s sometime now. When we have Battle of Britain Remembrance and you go behind our war memorial and you see all the names written and sometime you think to yourself what I probably, probably would be better if I will be dead with them then if you know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: Because you see —

CB: The sense of loss?

JB: Yes, because that was the friendship you see. We share sometime when we had to empty cigarettes packet and you came back from the operation and you notice cigarette were on very short, er, ration in those days, so you take, share with them you see. It was friendship, terrific friendship you see during the war.

CB: Um.

JB: I mean such a friendship will be in your heart for long time you see and if you’re gone with your friend in pub you didn’t wait if he probably was running short of cash or something not to share with him you know your money because us people were living together and facing the responsibility together. They were almost prepared to give life, one for another, you know what I mean.

CB: Um. Indeed.

JB: You see, today is difficult for people to understand such a friendship.

CB: Sure, because the crew was the family.

JB: Yeah it was family, it was family.

CB: Now the crash was in a Wellington but this is three — then you go to 300 Squadron and that converts to Lancasters?

JB: Yes, yeah. We passed our conversion on Halifax’s in Brighton and from Halifax’s into the Lancasters. Yes.

CB: Oh Right. So you went to the Halifax, from the Halifax through the Lancaster conversion school?

JB: Yes the Lancaster that was seven crews you see.

CB: Yes.

JB: Yes but before you go on a Lancaster the Halifax’s, that’s a four engine bomber. So from Wellington you go on Halifax and from Halifax’s into the Lancaster. Yes.

CB: Yes. Yes. So they, when you returned to East Grinstead, you were on Halifax’s?

JB: No from gunnery school.

CB: Yes.

JB: From gunnery school, my squadron then was sending from Wellingtons into the Lancaster.

CB: Right.

JB: And at Faldingworth Station, was built by Wimpy. It was first new built aerodrome that was 1900 Squadron moving in you see near Market Rasen. Yes.

CB: So you then, having converted onto Lancasters.

JB: Yeah.

CB: You then went on ops from there. How many ops did you do on the Lancasters themselves?

JB: Eighteen.

CB: Eighteen?

JB: Yeah.

CB: OK. And then you were called to East Grinstead?

JB: To East Grinstead, yes.

CB: How did you feel when you heard about the loss of the whole crew in the Lancaster?

JB: Oh, it was really I think the same probably as I would lost my father or mother or brother you know. That was the same because you see we during our flyings we were such a close together, you know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: When we went for holiday we share our money if we had money when we had no more money we return back to the station. You know what I mean. We shared together and we had one pay master. We give him our money. He used to pay our lodging. When we had holiday we usually gone together, you know what I mean.

CB: Right. We’re stopping there. Thank you.

JB: Yeah.

CB: When you left the RAF —

JB: When I left the RAF yes.

CB: What did you do?

JB: When I left the RAF, yes, I got job in the rubber factory in Southall. The name of that factory was [pause] Woolf, Woolf Rubber Factory Company, Southall, Hayes Bridge. Hayes Bridge that’s the name of that district, Southall.

CB: What did you do there?

JB: I, I was young and they give me opportunity to train me as a machine forcer setter [pause] I start in that factory to do night work. Twelve hours at, twelve hours night, twelve hours shift. I worked there twelve years [long pause] having one Sunday off. After twelve years [pause] I left and work for, as a rep, for the electrical company. With the electrical company, Clark Electrical in Willesden. I worked twenty-two years knowing all the cities in England I travelled as a rep and my big boss in that electrical company, the name Mr Jack Clark, died and the company, company was sold.

CB: Oh.

JB: And I reached my retirement age you see and that was the end of my civil life. So I had two jobs, one in twelve years and one twenty-two years.

CB: Brilliant.

JB: Yes.

CB: What did your wife do in that time?

JB: Oh yes. My wife in the end work in Carlton Tower Hotel, Sloane Street, Knightsbridge.

CB: what did she do there?

JB: That was the first American hotel built in London.

CB: Oh was it.

JB: The Carlton Tower.

CB: Yes I remember it. Yes. [long pause] So she stayed there all the time?

JB: Yes.

CB: Good. And how many children did you have?

JB: My wife had caesarean operation could not have no children.

CB: So that saved you quite a lot of money?

JB: Um.

CB: That saved you a lot of money?

JB: Yeah, yeah. I bought little old house in, in Holland Park, that’s when I made my money in the rubber factory you see.

CB: Yes.

JB: Yes. It was dilapidated house because during the war nobody could get no paint, no — you know because — and the roof was leaking but I liked the place Holland Park, you know. And as you know property start going sky —

CB: Sky high yes.

JB: And the things start to improve but the work was after the war, there was no, any, I would say, support like now people get.

CB: No.

JB: You had to get up early in the money whilst there was some job going because after the war in England was very difficult, very difficult. Every food was on ration you see. You went to the butchers shop you could get six rasher of bacon or half butter cut, you know, on how you say one pack of butter that was cut in half you see because on coupons.

CB: Yes

JB: Everything was on ration. Shoes on the ration. But afterwards slowly year by year when factories start turning into the commercial things start to improve.

CB: Yes.

JB: Lots of big emigration people used to go to different parts of the world from to America, Canada, Australia. Because during the war the most factory were producing for the war.

CB: Of course.

JB: Essentially you see.

CB: Yes. Yes.

JB: And it took them time to restart afterwards.

CB: Um.

JB: But when they started and you had strength to do it there was lots of money could be made, you know what I mean.

CB: Yes.

JB: It was hard, hard.

CB: Hard work.

JB: Hard working but there was overtime, there was factory was working you know all year round without stopping because my rubber factory I could set forcer machine on any production today.

CB: Right.

JB: Like Firestone, Goodyear, Dunlop because most of the rubber factories they have same machine forcers you see. And I was young and I was supervisor.

CB: Right.

JB: Yes. But you have to in those days there was no strikes, you know, because was union after was started, you know, emerging and there change came and was perhaps getting lots of new rules and so on. But when the factory started after the war they kept going for many, many years because there was such a shortage of domestic products. Our, the biggest customer was Ford and Dagenham. We used to produce to Ford and Dagenham all our rubber installation into the cars because before in the car all the rubber installation in window doors was all rubber. Now it’s plastic

CB: Yes.

JB: It’s different. And the Ford lorries used to wait outside our factory day and night. Soon as you cure our products they were —

CB: Right. Taken there.

JB: Rushing to Dagenham.

CB: Right.

JB: Because Ford had such a big orders for so many cars they could not change it they used to wait outside our factor, lorries, drivers soon as we produce and cure they were quickly because it was so —the rest of the world was such a shortage of cars.

CB: Yes. A couple of final questions. What was your wives maiden name?

JB: Evelyn Black.

CB: And we call you Jan Black.

JB: Yes.

CB: What is your actual surname?

JB: Jan Black.

CB: Yeah in Polish. What’s your Polish name?

JB: Oh. Jan Stangryciuk. Very difficult.

CB: So when did you change your name to Jan Black?

JB: Yes. I’m glad you, you see— I tell you something. When I, when I was with my de-mob money you see, eight years I thought I take my wife on holiday to Argentine you see and I probably thought I settle in Argentine. So my doctor said, Archibald McIndoe, that big plastic surgeon in hospital because he was not our, he was our friend, our advisor, you see that doctor to us he give us almost new courage to continue our recovery because we were partly broken.

CB: Yes. Yeah.

JB: You know what I mean, destroyed, we were ashamed to go between people, yes. He said to me, he said what documents you have. I said Sir Archie, I said I have no any documents. He said you should have British passport. I said to him I don’t know how to, how to make British passport. Don’t you worry for you will arrange for you. Because he said because if you go to visit to Argentine now you must have some documents but when I came here they didn’t want any documents [laughs] I probably have from school some certificate, you know what I mean. So you see, and of course because my wife was the name of Evelyn Black so they said to me we’re not going to give you different name you have same name like your wife, you know what I mean [laughs] but I tell you why. When I applied to the Argentinean Embassy for visa, because in those days you needed visa to go to, they were so interested about my past in England in eight years in the Air Force and so on. And they ask me if I agree so they put in local paper in BA my arrival that I serve in England in the Air Force eight years, I had my accident and so now I am returning to visit my family I said that’s OK but when they called me when my visa ready I went to collect my visa they said to me Mr Black but we have little more problem to ask you. As you know there is so many German different type of men who are now in South America we’ve been advised if you will agree of putting in local paper some of your visit to your family after eight years in England. I said but why is that the problem, they said because some of those men probably could be very unfriendly towards you because there’s so many men with those names unfriendly lots of, now circling in South American countries. So when I came to my wife and I said to her she said you don’t want know your name of your visit what you did in England and she said you had enough during the war, different you know, er, incidents, accidents and you don’t want to go now, you know putting in the paper your arrival and she wouldn’t have it. So I went back you see to the Argentinean Consulate and I said you know I’m afraid I want not to mention of my visit because so many Germans with big money, with submarines got — even the people there in Argentine up to now believe that Hitler was hidden himself in Argentine. What that’s what they said what they did — they got his you know body, his body in Russia somewhere. In Argentine there is still, in Patagonia, that’s a part of Argentine.

CB: In the South. Yes.

JB: Where lots of German community live. Eichmann after so many years you know they, they caught him up.

CB: Yes. Yes. They’re Nazi’s.

JB: Eichmann near my sister in Argentine. I have house, photo from his house. He bought that house near little airport. In BA, Buenos Aires, because Buenos Aires is a huge territory you know, you know London is big but Buenos Aires is also huge size you know what I mean.

CB: Yes I know. Physical size.

JB: So he bought that house, huge house near the airport. He already bought that with that big amount of money and he was living near that airport and had the plane in case of any problem he could easy get away because he had plane near Buenos Aires, small plane you know.

CB: Yeah, yeah. This is Eichmann.

JB: And that house so he easy could escape you know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: But the Israelis Secret Service you see there.

CB: Yeah, they got there

JB: And I have photos. You, I mean, I took when I went there to my sister holiday to Argentine with my wife. And that house is still standing as a museum.

CB: Oh is it?

JB: Yeah. A huge house. He was there and he had girlfriend and he promised her to marry. She was Argentinean and in the end because he told her he was single man, he was so and so but that girlfriend start to notice he was trying to betray her you know what I mean.

CB: Oh right.

JB: And staying there and, you see, somehow got in touch with the —

CB: The Israelis?

JB: Israelis Secret Service and that’s how they got him you see after so many years.

CB: Oh I see.

JB: But there’s still — what Hitler was not us, it was in the Europe where the Russian got his body or something but he was in, in Patagonia with stronger German [unclear] two in Argentine places, Patagonia one territory with lots of German emigration and another one what is in one of those parts you see.

CB: Right.

JB: Where you know he spent the rest of his life

CB: Yeah.

JB: In Poland?

CB: Yes.

JB: Yes, I was, my people were farmers in Poland and of course I was going to school and helping, you know, my parents you see. Agriculture worked in. Yes. And then when my family decided to emigrate to Argentine and in 1934 we had all the docs, immigration documentation complete we went by sea to Argentine and we dock in Buenos Aires. That’s the capital city of Argentine. Then after, after [pause] seeing different part of Argentine my family settled in province named Misiones. That was big province near Brazil, Brazilian boarder. Then, then I starts school in Argentine to learn Spanish and to uplift my further education. Then after living four years in Argentine the war broke out in Poland and my country was invaded by the Germans in September 1939 and after ten days the Russians attacked my country from the east. To me it was very sad time hearing all the news and destruction what my people start to suffer under the German and the Russian occupation. And every day I was reading in the newspaper how continuously different, different system was in force on my people and I start to feel very sad for my country. Then after about three months, in the Polish newspaper printed in Argentine, there was very happy news I receive. What the Polish people and the ordination could volunteer to come to England and to join armed forces and to fight against the Germans. I went from my homeland in Argentine to capital city Buenos Aires to the centre, where we had to report our intentions of joining as volunteers and to come to England. When I arrive at that centre we’d been check by medical board and we had tell them why we decide such a decision to come. And it was very straight forward answer, what we just wanted to go and fight against aggressive occupation of unfriendly nation. After having medical check up, we’d been asked when we would like to go to England. I told them soon as possible and the person who was in charge at that time told me what they will check my health and if I want to go soon they will notify me in two weeks, and they told me I can go home and wait for the next information. After two weeks I receive letter and a ticket, railway ticket that I can come to certain centre in Buenos Aires, the capital city, and I would be accommodated in one hotel. When I, on the second day, came to the meeting place I notice that there were different nationality volunteers. Polish, English, French and I was very happy what different nations also were coming as a volunteers. We’d been told in that hotel what we must keep our secret about our destination because there was lot of Germans espionage during that time circling in that part of the city. We’d been told what our departure will be very short notice given and be prepared on such an event. Then one evening notice was given to us at six o’clock and we’d been told what we will get transport to board on the big British liner from Buenos Aires port, when the big boat will take us to England. The name of that boat, I remember, it was the name Highland Monarch belonging to the British Royal Mail Line. That company had four big liners continuously travelling between England and Argentine and they, what they, during that travelling between England and Argentine there were, they were bringing lots of meat from Argentine to England. I say food for the war days during the difficult times. When we started our journey at night, at twelve o’clock, very secretly we had been told what we must be very alert because our journey will be continuously in danger from the German submarine or big German battleship which are circling on the Atlantic Ocean. We’d been told to be always , have ready, wear jackets in case the boats get sunk, we will have life jacket attached and the boat was continuously during the journey not going on a straight course only circling, zigzagging to avoid be spotted and sank by the German submarine. The journey starting from Buenos Aires to England took, instead of three weeks, took four weeks because the boat was zigzagging and loosing lots of shorter distance between England and South America. When we came closer to England we’d been told what our boat would dock in Belfast, Northern Ireland because to come closer would be much more danger as during that time the Germans continuously kept bombing our port on west from western approach. When our boat disembarked us we’d been taken to the local hotel for a couple of days and then we were taken to Scotland to some military barracks centre. And then again we had to pass the second medical board from the doctors. Doctors during our medication and inspection bought us, ask us what armed forces we would you like join. We had choice to serve in the Royal Navy, Army, Air Force or other forces. I was young and I thought the most exciting service would be Air Force. The doctors told me what my medical board said it was good enough and I, if I want to serve in the Royal Air Force I can make already decision what I will be, will be accepted. Then we’d been accommodated in some army barracks in Scotland and start telling us what now we will be sent to different centre when we start to continue our trainings. My selection was decided to send me to Blackpool where was Polish RAF centre for beginning my training to start learn of my future responsibility. After studying such trainings for months will be taken to special RAF centre. The centre it was 18 OTU Bramcote. When we start to continues the next training with flying. That training was very exciting for young men like myself, but it was very speedy training. We had not too much time to have, for other exciting moments. Training was long hours of different responsibility to get us ready, equip for responsibility we would be facing for our future flying. I was happy to start my training flying on Wellingtons to wing engine bomber at that time and I knew that soon I will be selected to the operational squadrons, but during that time we had to go on evening [unclear] training. During take-off my Wellington had fault in one engine during take-off. We crash during that take-off and I lost consciousness during the impact of our crash. When I recover my memory I could see what part of my plane was in flames. I start walk to the front of my plane and see what happening to the rest of my friends. When I reach the position where my pilot was sitting I saw him in his special seat. I did try to get him out of the burning plane but he was still strapped in his seat and during that time the plane was quickly increase in the bigger burning flames. I knew and I could see how to un-strap him from his seat and I cover my left side of my face because the flames were obstructing and burning my visibility and helping myself with the right of my hand looking for exit from the burning plane. Luckily at moving inside in that burning plane, I was lucky to see what my plane during the impact had crack in its construction and there was broken exit from that plane what I was lucky to squeeze myself from the small hole of my burning plane, but I already couldn’t see normal because my eyes were already damaged from very strong flame was burning round the plane. I start to crawl a certain distance from my plane and the local people found us. Came to my rescue and they torn my burning combination suit because without that help I would be completely burned to die. I was so lucky what those people were so brave and came so close to that burning plane and they took me inside into their local house but I couldn’t see nothing because my visible, visibility was damaged. But they told me that they had already telephoned for ambulance to come. In about half an hour ambulance came and they took me gently into RAF Hospital Cosford near Wolverhampton. I was in terrific pain. I was so happy to be dead at that time because it was such a painful experience what I had to go in my lifetime. But the doctors soon came to my rescue. They told me don’t worry your pain soon will stop. I didn’t believe them but they had the answer to it. They give me certain tablets and I think some injection to stop my pain. When I recover my memory, I think it was the next day, I could not see nothing because my eyes were damaged but the doctor came and talked to me and told me that I will be making progress with their help. I thanked them very much but the most biggest thing I receive from them was my pain was already under control. Then my small recovery started day by day. [clock chiming] The nurses every day would take me to the bathroom, put me into the bath and gently try to remove my bandage that I was strapped on my head and on my hands. That bandage was soaked with a special oil so that oil prevent so the bandage doesn’t get stuck to my burning flesh and they gently will remove that bandage every day and cover me with the fresh new bandage. After having the same routine day after day, after two days I been told that a very special doctor will come to see me. The name of that doctor was Sir Archibald McIndoe. He was one of the biggest plastic surgeon doctor in the Royal Air Force Hospital, Queen Victoria in East Grinstead. He came that hospital to RAF hospital in Cosford and to see certain airmen from different accidents. When he came to see me he told me his name and he told me he would like to transfer me to his hospital in East Grinstead and ask me if I will be happy to go to that hospital. I turned to him and I said to him ‘doctor I leave all the decision to you because you know the best about my problem and what to do with me’. He was happy to hear that my great thanks to him that he wanted to take me to that special hospital in East Grinstead. The next day ambulance took me to that hospital. When I arrive in that hospital I’d been told there are so many boys from different accidents and different nationalities. There were English, Canadians, Polish and I think some French. I was so happy to be in such a friendly hospital. Queen Victoria Hospital it was one of the most famous hospital in the world for the badly burned, disfigured young airmen and the city, small town East Grinstead. It was our, the most lovely place maybe in England because those people understood and feel our disfigurement and they never stare at us in such bad disfigurement as we receive from different accidents. East Grinstead give us hope to continue, having such a big hospital with such advanced capability to improve our standard from the most horrible disfigurement what the fire could give to you. Must stop now.

CB: Right.

JB: How we play this, you know broken mentally now. You know what I mean?

CB: Yeah, they knew how you felt.

JB: Yes you see because you come to London people don’t, when they see you in certain still disfigurement they think, think probably you come from other planet or something. [laughs]

CB: [laughs] Yes, yes. Can I just ask you one thing and that is what happened to the rest of the crew because there were five of you on the aircraft or six?

JB: Yes. There were, I was one and the rest died. I was the only one that survived. Yes.

CB: Yes. Right. So you were flying as the co-pilot?

JB: Um.

CB: You were flying as the co-pilot?

JB: No. I rear gunner.

CB: Oh, gunner?

JB: I was the rear gunner.

CB: Oh, right.

JB: Yes, yes.

CB: OK.

JB: I did try to save my pilot because, but by the time I tried to reach the plane was in flaming.

CB: Yes.

JB: In bigger. So I covered my left side and tried with right hand so I burned my right side you see. Because you can see it you see you lost your visibility and the way to find the way you just had to with one hand. Even in your hand you was using feeling because hands was burnt. Fire you see. The biggest enemy what you could face.

CB: Absolutely. Yeah.

JB: Because I was — three times I see young boy drowning I say but you can fight drowning, but fire —

CB: Fire you can’t.

JB: It puts you out of completely, out of control you see. Fire the biggest enemy what you could face.

CB: Dreadful. Yes. So how soon after take-off did the engine fail?

JB: You see, what I want to, ‘cause I asked for break.

CB: Yeah.

JB: Then after spent six months in hospital. Hospital was getting so overloaded with new cases coming night after night and they were running short of beds, so what they used to do they sent you back to your stations for certain time.

CB: Right.

JB: And they patched me up. The beginning of my recovering and I’d been told what they cannot do another operation because I must have certain recovery time you see.

CB: Right.

JB: And they got in touch with my station but I would be discharged from hospital for short time and my station send me railway ticket from East Grinstead to Scotland, to Evanton near Inverness to gunnery school. And in that place there was, they give me instead of having a bit more recovery I had to continue flying with the new course, batch of gunners who come. Flying Boulton and Lysanders so the new gunners always be — I already was advanced as a gunner and give them instruction how they have to continue the more — the rest of their training. How to shoot the Lysander whose pulling behind him they sat and they firing from the Boulton twin engine plane with the [unclear] turret. Yes. To teach them how they have to see the distance. When the Lysander approaching them and they will be able to know the distance from what distance they can open fire, shooting to the Lysander sat which is dragging behind. And sometime it was very, very danger, you know, because the new gunners they had no hundred percent control of what they were doing. Sometimes they turn bit too much quickly and they shooting instead of sat and they shooting closer with the pilot you know flying Lysander. [laughs] So the pilot talk to me on the intercom ‘what’s happening? Can’t you see what’s happening?’ I said ‘yes skipper, I see what’s happening’. You know, I said, you know that’s not going to happen again. So I run to that gunner and I say he must move the turret gently not you see, but they kept not feeling it yet. So I continue that training for three months in Scotland. Evanton near Inverness. And after three months, after three months I went to my commanding officer and I said to him I said ‘Sir, I would like very much asking you for one favour. If you could give me permission to be sent to my squadron.’ And the commanding officer in the gunnery school asked me why I want to be transferred. I ask him after having three months responsible job what I was doing I found I just cannot continue, you know, to do that. He said ‘you will do that’ but he said I must wait another few days. I thank him. After, I think four days, I had my railway ticket with the rest of my documents, discharge from that station gunnery school to my squadron. When I arrive to my squadron, the next day I had to report to the commanding officer. My commanding officer ask me why I asked to be transferred to that station. I told him what I spent three months as instructor in that gunnery school and it was just too much to continue and he ask me what I want to do on my station. I turned to him and I said ‘Sir, what I want to do, I want to do same thing what I been taught told what to do. I been teach to fly and do my flying job.’ He said to me will I be, if I will be able to do that. I said to him I think if I did already three months as instructor in the gunnery school, I am sure I will be able to continue to do the rest of my job. He said alright but, but they still send me, he send me with two doctors for two hour flying and the doctors kept talking to me during those two hour flying, looking at my reaction and my, and my [pause] and my, how I feel if I’m not nervous or something or they could notice, not capable to continue to do my job as I ask my commanding officer that I wanted to fly again. After two days my commanding officer saw me and told me what the doctors give him result without no problem so I can continue to do my flying again. I restart doing my operational flying and at one time I receive letter from hospital and hospital ask me to go back for the continuation of the rest of my treatment recovery. I took the letter and gone to my commanding officer and show him the letter and commanding officer turn to me and said you should be very happy what the hospital want to continue to improve you, the rest of, give you treatment. He said you should be only too happy to that hospital and he said I must go. On the third night after departing from my station and departing from crews what I was flying with them. On the third night they went on the night mission and never return. So you know my history, twice luckily, you know had enough luck probably you know not to end up with the rest of my friends, you see. By the time they finish my, the rest of my treatment the war was over, but I still serve ,still serve three year longer, longer. You know, because I was young and they were discharging mostly older people. And in 1948 I had my discharge from Dunholme Lodge, the discharging station, Dunholme Lodge in Lincolnshire. Yes. And that’s when I started to go into the civil life. Then I got married to my wife. That’s why because I didn’t marry her during the war because I told her the war brings so many unexpected changes but when war ended we, we give each other promise so we get married. And we kept to our promise [pause] after living with my wife for fifty-two years [pause] I promise her what I will never leave her. So when I die I give her promise I will be buried with her together and that’s what I will give, going so you see I thought England is my country, my history here. They called me when it’s Remembrance Day [unclear] London Royal British Legion I felt if I go back to Argentine, I took my wife to Argentine I ask her if she like to see my family and we went by boat because during that time, after the war it was not such a long distance plane flying, so we went by boat. Three weeks going there and three weeks going back. But Argentine was changing after the war, different Government, different changes and I thought I was already more adjusted to life with my future wife in England. We returned and restarted our civil life and now I go to Poland for short holiday. I got some time to Argentine now, it’s easier to get there but I thought I came to England when time was difficult and we achieve our aim and this country had guts to stand up, you see and to [unclear] enough was enough without England the world would be different today. So that’s what I did for this country. There was nobody else could stood up. The English had guts to do it and the rest of people would join.

CB: Um.

JB: And without such a decision probably, you know, I don’t maybe for a thousand year the world would be different.

CB: Um.

JB: But you see the people, young generation don’t know what took [unclear] you see I saw in my squadron when sometime you come back and that table it was empty in the dining room and you thought sometimes think to yourself when my table will be empty. Because we could always eat together. We be like brothers if you know what I mean. And we — whatever happened after the war we made Europe different for so many years.

CB: Um.

JB: The people parted in different parts of the world now making destruction and so on but we show the world what Europe will change and I think this whatever we make changes we should be happy that so many people give their lives in the second war. But we must always remember that we don’t want to go back to the old days what Europe was, you see.

CB: Um.

JB: And we, we had our — the one thing after the war I was really heartbroken when Mr Churchill was not elected as our leader because I thought in the most difficult time when he took over, er, we should have given him that big recognition what he started in difficult time and achieve with the rest of the people in the world such a great victory and recognition and using the election, you see because I think that was the biggest mistake what we make after the war. Because with him I think we probably would be still much better off, you know what I mean, because that meant was seen all over the world you see.

CB: Um.

JB: But sometime politician do make mistakes too, you know what I mean. Men go, will fight and do his job and the politician make mistake too, you see. But that’s how things go, you see. To us and it will be continue.

CB: Um.

JB: And I mean I have sister in Argentine. She’s younger than me, a few years, and she said to me why don’t I go back and live with, with her and her children. I said no, I said I came during the war, I was a young man, I found my girlfriend here during the war and I said I would be feeling lost there, you see. Because I said, I in this country have some recognition you know. What I did, I mean if I would go to other country, even in Poland it wouldn’t be the same like here.

CB: Um.

JB: You see I belong to the Guinea Pig Club. Duke of Edinburgh [unclear]. He’s our president of our Guinea Pig Club, you see. He used to come sometime if he was not abroad to our dinner in East Grinstead. I had couple of times chance to talk with him, you see and that give you something what you, you used to have special days, Remembrance Days. Royal British Legion give me invitation to all the smaller things and you, you just feel you don’t want to lose that recognition, you know what I mean.

CB: Um,

JB: I will not receive that in another country. Yeah. And that myself what I as a young man came from the Atlantic all ready because I was feeling hurt what my people suffer of two unfriendly nation. Russia and Germany and I thought it was all wrong what we in Europe in those days for so long had so many times, you know, continuously such an unfriendly living. Yes. And now whatever look, year seventy over seventy years people travel you saw no fighting we give the rest of the world example what they should take same thing what we did. You know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: But we don’t know how long it going to last because you see because there new super power emerging with nasty ideas. Yes. And that’s why those [unclear] sooner or later will be happening all over the world. There’s nothing worse when dictator get power, you see, because they don’t listen to nobody. I mean those big dictators, you see when they done, have democratic system they take power into their hands and that’s what always was not much future during. Luckily we got rid of them [laughs] but some as soon you got rid of them then some new emerging [laughs] yeah. But, we took, when we took that big decision in 1939 and Mr Chamberlain used to, Neville Chamberlain used to go to Hitler and ask him what you, why you continuously want more, you already took so many. And he used to always promise the British Prime Minister there would be no war you know. But the rest of the world knew that the Germans was arming themselves and preparing themselves for the big expansion of their empire. You see that’s why [unclear] Germans because they wanted they could get pressurising Poland what Poland should give them [pause] chance to march, attack Russia because they knew that Russia was such a huge big country. And they knew it would be easy to, in those days, to overpower that part of the Eastern Europe. And Poland they wanted no German friendship nor Russian. They used to live between two very unfriendly neighbours you see. And that’s what happened, you see. And Hitler, you see, in the end took power into his own hand and he was gaining without fighting from beginning. Yes. And if in those days there would be no England there was no other country who would be stopping his expansion here because he already had everything going easy, easy. And even after when France collapse, look he was almost big military hardware which he recover from the French. I mean he used to make himself from strength to strength you know, without. He’d overpowered Czechoslovakia, took very big modern small industry, Skoda. Took the French, you see, military hardware and he was gaining from strength to strength he was building himself. It’s a good job there was one country still standing in the world. What they knew they cannot give in no more and they told, told on the last many meetings of Mr Chamberlain had what if, if he continue with Poland because Poland had treaty with England and France at that time. What the world will be unavoidable. But even so he took so many chances and he gained without problem and he thought it would continue but he made mistake you see. But the British decided they were going to stand up to it. Yes. But you think, you think there is the world that’s why in Europe now you see we, we should have much bigger recognition, you know what I mean in, in that. There’s twenty-seven countries, yes but we should be classified you know exactly as equally you know because there is difference between one country and another, you see. And the trouble was immigration was big problem for long time, you see, because now they well staffed to notice that what you know we must do something and cooperate not listening just to one country, you see, because it is a world problem you see and, but Europe didn’t listen much you see and that’s probably what ever happening changes or we don’t know how it’s going to end, you know what I mean.

CB: Um.

JB: But it was problem because they used to come to [unclear] and not the one country was selected the most of them wanted us England, you know what I mean, because it was the most place where they could get the easier living and you see Europe then should talk it out more into consideration what they should cooperate together. I mean the Syrian problem started, Europe start to wake up you know and notice the big problem to the rest of the world but there is not only secondary there is African problem yes coming. And Europe must work together to stop that because one country cannot do it. Now, now after all these years [unclear] tried to clean it you know what I mean. For how many years and it was spreading because during that time lots of people were making money out of it you know. Everybody had fingers in it, you know what I mean.

CB: Um. Um.

JB: You see the French were very, I would say, to, to have less responsibility because they, they had their country and they should probably knew what lots of people who come from different parts through their land come to the English Channel and heading, you know to England.

CB: Um.

JB: And for so long it was continue you see, but the, like, you see, in the many, many different ways I think the France took big res — less responsibility they, they start to feel under own problem you see and that’s what happening but probably that should been stopped long time ago, years. But politicians have time to make mistakes you see. And that’s we probably don’t know how going to end you see.

CB: Let’s just stop there for a mo. Now you mention that you had a girlfriend in the war called Evelyn.

JB: Yes, yes.

CB: And where did you meet her?

JB: Yes.

CB: And what was she doing?

JB: I, I met her during the war one day at the Hammersmith [unclear] at a dance [laughs] yes. Yes.

CB: So how did that come about?

JB: Er, well you see Hammersmith was very popular part of London where was lots of during the war activities and there was very famous for dancing you know [unclear] dance and I met my wife but she, she was, er, coming from the Derbyshire, Matlock in Derbyshire. Yes. And my wife during that time was working in cafe royal syndicate. Yes. And I ask her why she’s not going back to Derbyshire and she told me because she come from big farm in Derbyshire but her father send her to London to finish her economy programme. When she receive her degree in the economy she decided that she find better reward living and working in London. And she decided to stay in London and when I met her during my first meeting I ask her why London is her select place. She told me because working on the big farm was very responsible and heavy daily responsible life but she was always happy to tell me what the Derbyshire will always be her, the most lovely part of the country. But one time I ask her why and she told me if I ever heard the name Rolls, Rolls Royce I say yes that’s one of the famous place where they produce the biggest engine for the planes she told me because the most famous people live in Derbyshire and I always will remember her sorts of proud to come from that part of the world. She was very understanding person and I promise with her what when war ended and we survive during the war, if she decide to marry me I will give her promise I will do that. War ended and we kept to our promise. And I will remember what we kept that till the very end. She was very good wife and my memory will be continuous of my happiness what I spent with her for so many years after the war. Yes.

CB: When did she die?

JB: Um.

CB: When did she die?

JB: Oh, eight years ago.

CB: Right.

JB: I bury her in Gunnersbury cemetery.

CB: Oh Gunnersbury. Right. Right.

JB: Yes. Yes.

CB: And it’s big enough for both of you?

JB: Yes.

CB: Let’s have a break there for a moment.

JB: Yes. But we knew the second war was brewing, from, you know, year two year we knew.

CB: Right.