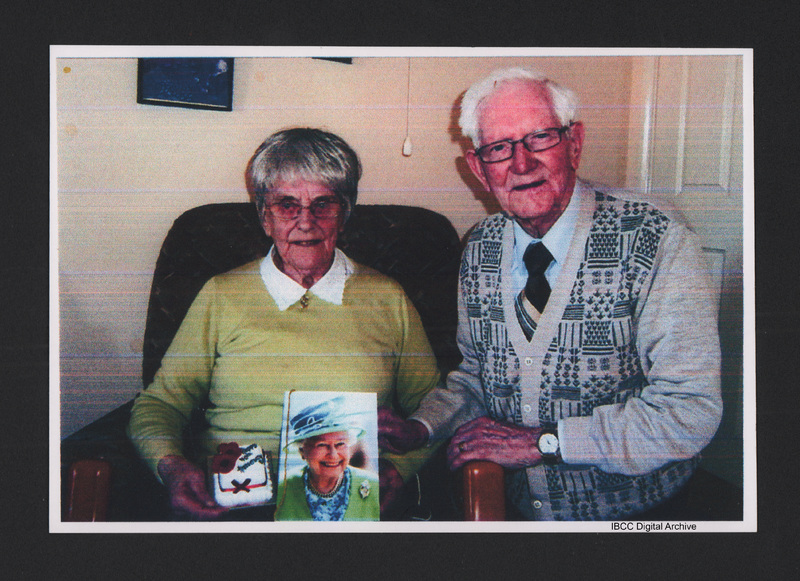

Interview with Charles and Margaret Ward

Title

Interview with Charles and Margaret Ward

Description

In 1940 when Charles was twenty he received papers to join the Royal Artillery and went into the Royal London Rifles. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force and was accepted but instead of joining the RAF he was ordered up to Scotland to join a special unit of tanks and artillery, then posted to North Africa in 1942. Charles describes a battle in Tunisia in which seventy-five per cent of the battalion were killed. While confined to camp with an injured knee an education unit arrived and, after taking a number of tests, he was posted to Special Operations Executive and worked in Algiers and Italy as a cipher operator. Charles describes his work as a cipher operator including giving coordinates for planes to drop agents and supplies. He met his wife, Margaret while in the Special Operations Executive and Margaret gives an account of her work as a wireless operator. She also describes how her mother joined the WAAF even though she was over forty.

Creator

Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:18:11 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

AWardC-M160219

Transcription

CB: My name is Chis Brockbank and its Friday the 19th of February 2016 and I’m in Aylesbury with Charles and Margaret Ward, both of whom were in the SOE, the organisation people weren’t supposed to know about but, er, was dealing with clandestine work not just in Europe but elsewhere. And I’m going to start talking with Charles with his earliest recollections and how he came to join the SOE and what he did. So Charles what’s the starter on that?

CW: I was born in Yorkshire in a mining village and, um, eventually went to school at, a grammar school, and eventually I — there was no, very much work around up there but eventually an uncle and aunt came to visit us, who lived in Dartford in Kent, and they said where he worked it was a printing firm in Dartford, and where he worked they needed an apprentice, and I was fifteen at the time and they said if I would like to I could come and live with them and be trained as a compositor. So, I jumped at the chance and so I moved down to Dartford in Kent and, er, was being trained as a compositor. When the war clouds were gathering around, er, the Government decided that twenty-year-olds would be called up and trained ready for war and I received papers to join the Royal Artillery on Salisbury Plains but before the due date to report I was — war was declared — and I was called up to the London Irish Rifles and had to report to a station in London and, um, reported there. From there, from there we then trained onto the London Underground and taken to Southfield Station in South West London, um, marched down the road to Barkers Sports Ground, next to Wimbledon Tennis courts, where we were to do all our square bashing and training. And this happened for several weeks, er, before we were fully trained and then from then on we were stationed in many parts in England, various places, and eventually the battalion was training new recruits to go and be transferred out to other units and, um, I got fed up with the repetition that this was giving us [slight laugh] and by that time the Bat— the Battle of Britain had started and they were running short of pilots so they said they’d like volunteers from the Army to join the Air Force, so I volunteered. I was taken down to London, interviewed and passed all the tests and they said, ‘We’ll train you as a pilot. Go back to your unit and then you’ll hear from us.’ Having got back to my unit the, um, we was — then a few weeks later I — they stopped all transfers to the Air Force. We were taken up to Scotland to join a special unit being formed of tanks and artillery. This was prior to being shipped out to North Africa. So we went out to North Africa and landed at Algiers. From there we moved forward up into Tunisia where we had over a year of fighting the Germans in North Africa. It was quite a horrendous time really. We lost quite a few of our people and I have been out since to visit the graves of three of my men that got killed out there. And then, stop, I don’t know where I’ve got to.

CB: So we’ve talked about Charles joining in 1940. Then he moved around a lot he said. What, what were you doing in that time specifically?

CW: We were doing guard duty on airfields and RAF records office and things like that. I distinctly remember my twenty-first birthday was on guard duty at the RAF offices in the snow [laugh] and, er, after that we were training up people being drafted in to us and then once they were trained they were drafted out to other units. And this was getting too boring so I volunteered for the RAF and got accepted and, having got accepted, they then decided that our unit would join a special unit being assembled in Scotland ready to go out to North Africa of tanks and artillery.

CB: So which year are we in now?

CW: That’s 1942.

CB: Right. Operation Torch.

CW: Yes.

CB: Right, OK. And where did you land?

CW: We landed in Algiers. It was a troop carrier just in, in the port in Algiers. We were then trained and taken up the coast to towards Tunisia where we were then taken into the mountains, er, as a defence ready for attacking the Germans.

CB: And were you at this stage on tanks or were you on anti-tank weapons or what were you doing, infantry?

CW: We didn’t see the tanks in, on that occasion apart from on the plain, the Gudlat [?] plain in front of us. You could see the tanks moving but we were stationary until we did an attack one day on hill 286 and, um, we had we had to move from our position in broad daylight to get into positon to start an attack the next morning at dawn and this was in full view of the enemy and I said to my people, ‘As soon as we get in the middle of this area we’re gonna — all hell will break loose. We shall be bombed.’ Which we were and the only casualty we had was our platoon commander got shrapnel in his back and we eventually dropped into a wadi, which I thought would be quite safe, and we moved down this wadi and — to get to the position where we would form up for the attack the next morning. And, er, moving down this wadi what I heard from nowhere, I don’t understand where it came from, which is probably my guardian angel, one word which said, ‘Run.’ So I shouted to my chaps, ‘Come on!’ Ran down the wadi, turned the bend and no sooner got round the bend then a shell fell right in the wadi, injured three of my people. I went back, patched them up as best I could and stayed with them until the stretcher bearers came, er, then continued on to do the attack the following morning. The following morning we did this attack, um, because we’d lost our platoon commander the, the other two platoons were in advance and we were in reserve and we went over the hill and nothing happened; over the second hill, nothing happened; over the third hill and all hell broke loose and they, they were just machine-gunned. We lost about seventy-five per cent of our personnel during that battle [sniff] and then we were formed up in, dropped into the wadi again, for protection, stayed there overnight but at dawn the next morning there was a counter attack, so we just had to get out of it and, er, we all retreated and after that battle we were rested, er, and [sniff] can you stop a minute? [background noise]

CB: Right, we’re just getting a bit more detail on this [clears throat].

CW: When the attack went in and the two platoons in front were machine-gunned, um, the rest of us were left in a large depression in the ground being shelled and I suddenly discovered with us was a, a Royal Artillery observation officer with a wireless set and he, he ordered me to the top of the hill to find out where the gun was firing from. So, off I went to the top of the hill, saw that it was coming from a farmhouse down on the plain, got back to where our positon was and found out a shell had dropped exactly where I had been lying.

CB: Wow.

CW: So, um, that was —

MW: Smokescreen.

CW: Yeah. He then ordered a smokescreen and we were then able to get back to the wadi and then —

CB: He got his guns to fire a smokescreen?

CW: Yeah. He radioed back and got the guns to put a smokescreen down so that we could get out. So, off we went and back to this wadi and from the wadi we had the counter-attack. So we had to retreat and reform up eventually with only twenty-five per cent of the battalion.

CB: Amazing. OK. So then you rested a bit, then what?

CW: We, we were rested and re-enforced and we did an exercise, which was a ten mile march and, er, did a mock attack of house clearing, during which I banged a knee, which had been damaged in football previously, which began to swell and we did a ten mile walk, marched back and half way back I was limping with this knee problem. The CO drew up in a truck beside me and said, ‘What’s your trouble?’ [slight laugh] And I said, ‘I just banged it and, you know, it’s swollen up.’ He said, ‘On the truck. Report sick when you get back.’ Which I did and, er, we had hot and cold compresses and [unclear] on it, which had no effect whatsoever and eventually they said, ‘Well, you’re no good to be infantry. We’ll have to down-grade you.’ So, from being A1 I was downgraded to B1, sent back to a transit camp at Philippeville. There with — I couldn’t walk about because it was painful, I had nothing to read and it was so boring [slight laugh] I was just going mad. I then was transferred to another transit camp at Algiers, just outside Algiers, and same thing, nothing happening, nobody took any notice of us. We just stagnated there until one day on the notice board there came a notice to say that an education unit would be arriving and anybody could volunteer and they would try and find you something to do. So, I was top of the list and they came. Education test in the morning: English, maths, geometry [?], starting from the simplest and going up as far as you can, even Pythagoras and beyond if you could. And whilst they marked the papers in the afternoon they would give us a mechanical aptitude test. They threw you a locking piece and said, ‘Put that together and then you’re going for an interview.’ And, um, the officer said to me, ‘What would you like to do?’ And I said, ‘I’d heard they were starting an Army newspaper in Algiers and I was a compositor. I would go on the army newspaper.’ And he just laughed and said, ‘I don’t think there’s not much chance of that. What else would you like to do?’ So I said, ‘I don’t care as long as I do something. I’m going mad just doing nothing.’ He said, ‘I think you’d make a good cipher operator’. I said, ‘Suits me.’ [slight laugh] A week later I’m called into the office and given a move— moving order. There were six of us on this moving order and I walked outside, quickly looked to see where we were going to — no destination. So I shot into the office and said, ‘There’s no destination on here.’ ‘You’re being picked up,’ he said. So, the driver came and I said, ‘Where are we going?’ And he said, ‘I’m not allowed to tell you.’ [laugh] So, I wondered what I’d landed myself in for. Off we went in the truck and the other side of Algiers it was a, a large holiday home complex built on the sands, villas all on the sands, being surrounded by barbed wire, guards on the gate, and in we went. Going inside there was Army, Navy, Air Force, civilians, and everybody including girls [augh] and this was a radio station which was — belonged to SOE, working to the agents in France and Italy and Yugoslavia. There I was trained as a cipher operator and worked there for quite — a year, worked there for a year. During that time the sergeants’ mess decided that for entertainment we would do dinner dances about every fortnight and invite the FANY girls who were on the camp. They were radio operators and secretaries and, um, there we had these dinner dances. I teamed up with a Margaret, a different Margaret, I teamed up with a Margaret as a dancing partner until such time she went on leave and then I teamed up with Margaret, who’s now my wife, and we had a year working together on the same camp until such time I got a moving order to say I had to go to Yugoslavia. We exchanged addresses and said, ‘If you’re my way pop in, you know, it would be good to see you.’ And, er, off I went to the airport. We had to fly to Bari, then down to Taranto and then get the boat over to Yugoslavia. Having got to the airport there was the most violent thunderstorm. The plane couldn’t take off so a twenty-four-hour delay. Took off the next night. Halfway across the Med, er, one of the twin engine, one of the engines of this twin engine Dakota, started misfiring so the pilot said, ‘We’ll never make it over the mountains to Bari. We’ll have to land Naples.’ So, down we went to Naples, another delay. Eventually we got to Bari, walked into the office in Bari and they said, ‘Oh, sorry. We’ve sent people from here to Yugoslavia. You’ll have to take their place here.’ So, er, settled in at Bari. So, a month later I’m de-ciphering a message which said the following FANYs will be joining your unit so I quickly looked down and fou— found Margaret Pratt was on the list. And I quickly made contact with Margaret and we had another year together in Torre al Mare, just below Bari, in Italy. There we got engaged. Can you stop there?

CB: So, we’ve talked about you being in Algiers and then going to Bari in Italy. At this time you’re a trained cipher operator but what exactly did a cipher operator do?

CW: He made plain language into codes which could be transmitted by wireless and we started off with the agent had, um, a book, a book and we had to copy exactly the same and they, um, used pages and lines and the number of words in the line on squared paper. And then the A in the line was numbered 1 and second A, 2 and all through the alphabet. So we had numbers on top of the lines and then you read down and wrote across for a second identical one. So it’s a double transposition and, um, this was then transmitted by wireless and the agent could reverse the process the other end to get the plain language out but it had to be exactly right because if they made a mistake or if you made a mistake it was indecipherable. So, we had a number of indec— indecipherables obviously and when we weren’t busy with doing traffic at the time we had to work on the indecipherables to see — and we got to know that some agents did certain things so we could remember and do exactly the same to get them back to plain language. And then eventually we moved on to one-time pads which were figures, er, which were just ad-lib figures, you know, nothing about them. So, you had a one-time pad and the agent had a one-time pad and they had theirs on silk, printed on silk, which was easily got rid of if, er, if they had to if they were captured.

CB: So, here we are in a situation where you’re in the home station and the agent is, in this case, Yugoslavia, how did they get out there, the agents, and the, other staff?

CW: They had submarines and boats, um, which went across at night and this is one of the things that we decipherers had to send the night recognition signals and the places where they were going to be landed so that was — and if, if they didn’t get the recognition signals by flashlight they would— they wouldn’t row ashore.

CB: Right, and to which extent were aircraft used in this job from Italy?

CW: They, they were used as well to drop agents in, er, mostly dropping them rather than landing them. All the landing I think was done by sea.

CB: So, would they take any equipment with them or would that be a separate sortie in order to supply them?

CW: Mostly they took their wireless sets with them but, er, if they got damaged or anything we had to drop others by parachute.

CB: OK, and did they stay they all the time or were they plucked out every so often?

CW: They came back for reports occasionally.

CB: They did? Right. What was the survival rate like?

CW: We don’t know really because it never, the news never got to us.

CB: Right. I’ll just pause there a mo. It’s just worth stating here that this isn’t a regular Army operation, this is SOE, so you had a reporting line that wasn’t directly in the Army was it?

CW: No it wasn’t but before the SOE this is, I was on a football match, um, when we — after the North African campaign finished, um, on the touchline watching the football, and the CO came round and pulled me out and he said, ‘I understand they accepted you for training as a pilot two or three years ago?’ I said, ‘Yes, that’s right.’ He said, ‘They want to know if you’ll volunteer as a glider pilot.’ Which was obviously for the invasion of Sicily of Italy and I politely refused. I really didn’t fancy not having an engine with me.

CB: Yeah. Interesting so this is your CO? How did the rankings go? I mean, that was the same as a military rank but you were kept separate, same as an army rank.

CW: Well this is Army, before the SOE.

CB: This was before, sorry, right. So, now going to SOE, what, how were you categorised there in terms of — because you were separated, how did that work?

CW: We were still Army ranks and obtensibly in the Army, what they call it? Signals unit. The stations had various names. The one in Algiers was called ISU6 or Massingham. We had an air, an aerodrome at Blida, inland, where the dropping containers were filled for dropping in southern France.

CB: So, Massingham is the, the station code name for North Africa in Algiers?

CW: Yeah. That was the station called Massingham, yes.

CB: Yeah. So, was there a dedicated airfield for your people?

CW: Blida. Well it was at Blida but because it was so secret [slight laugh] it wasn’t, er, common knowledge. We also had a submarine in the harbour at Algiers.

CB: Oh did you?

CW: That went over to France and surfaced and rowed people ashore, yes.

CB: So, you were training people, were you? To go to Blida, the aircraft, Air Force station before being delivered or were they trained before they came to you?

CW: They were trained on the camp at Massingham.

CB: They were? Right. Yeah. And this is really for supplying France before you got, before the North African war finished, is that it?

CW: No, that’s after the war had finished.

CB: It had finished. OK, so when you went to Italy, to Bari, that was well after the invasion of Italy?

CW: Yes. The war was going up. Po valley was still a war zone, up in the Po valley.

CB: Right up in the north, yes, so they had capitulated anyway but we’re talking about 1944, are we?

CW: Yes that’s right. It was at the tail end of the war.

CB: OK, so how did it progress after this supply you were talking about, Yugoslavia. How long did that go on for and what happened afterwards?

CW: Well, that was quite involved because, um, you had Mihailović they backed to start with and eventually they moved over to Tito and —

CB: Mihailović was the loyalist, royalist? Yeah.

CW: I think most of the people were more concerned with what happened after the war rather than what was happening during the war.

CB: Right, so Tito was the communist and he was the one you were backing then?

CW: Yes, that’s right.

CB: OK, so we’ve come to — have come to the end, have we reached the end of the war yet or did you go somewhere after Bari?

CW: Yeah, when the war finished —

CB: What did you do?

CW: I did, er, a quick course on Typex machines, which is a keyboard, and then transferred to Athens where I spent a few months before being shipped home for demob.

CB: And what did you do in Athens?

CW: Well, basically enjoyed ourselves [laugh]. There was nothing much to do really. The war was over and we just had various messages to transmit, encipher and decipher but not many.

CB: Right, right. So, just going back a bit on the SOE front, the ordinary forces didn’t know about SOE?

CW: No.

CB: And how did you explain away that you were separated from them and why?

MW: We never mixed with them did we?

CW: Yeah. It didn’t occur. The only time we had any trouble really, if any of our people were picked up by the military police and then they were [laugh] had to be got out of gaol, as it were, by people from our camp, to go and say well, ‘These are our people. You’ll have to let them go.’

CB: But not knowing, not telling them why?

CW: Yes. ‘Cause the Unit said they didn’t know about ISSU6 and Force 399 and Force 133 —

CB: OK.

CW: All odd names they had.

CB: Yeah. So mentioning those, in sequence, what were they? So, ISSU6 iss MI6?

CW: ISSU6 was at Algiers but it was also called Massingham.

CB: Right. OK.

CW: And then going to Italy it was Force 399.

CB: Right. OK. Technically a signals unit as far as you were concerned?

CW: Yes.

CB: OK. Then what, what else were there in titles? What were you called when you went to Athens?

CW: I was back in the Army then. I was transferred from SOE back into the Army.

CB: Oh were you?

CW: After the war was over and trained on Typex machines and doing enciphering and deciphering for the Services.

CB: Right, so in the light of the fact the SOE was the “invisible force” you couldn’t talk about it. How did you assimilate back into the army without people tumbling to what you’d been doing?

CW: Nobody ever asked any questions, just assumed that I’d been transferred from a different army unit.

CB: Right. Right. OK. [background noise]

CW: Initially training on rifles.

CB: In the Army.

CW: In the Army on Rifles, Bren guns, and the PIAT, the projector [?] infantry anti-tank gun, but with the SOE there was no need to carry arms at all.

CB: So you went, after the end of the war in Europe, you returned, you reverted to the regular Army. Was that the point at which you did?

CW: Back, back into signals.

CB: VE, on VE Day.

CW: Yes.

CB: Right.

CW: Yes, into Signals and posted to Athens.

CB: Yeah, and what happened in Athens? Did you stay there right until your demob in 1946?

CW: Yes, I was demobbed from Athens, back to Taranto all the way up to Italy.

CB: By train.

CW: Up the French coast by train.

CB: Then after the war what did you do Charles?

CW: After the war, interestingly enough, um, I made straight for somewhere I’d only been once before which was Southfield Station, where I marched the other way down Wimbledon Park Road to where Margaret’s parents had a house [laugh] met her [laugh] and where we got married. So, having started the war there I ended it there.

CB: That’s where you met Margaret in the first place was it?

CW: No, Algiers. I met her in Algiers where I met her in the first place.

CB: Oh you didn’t meet her until then even though she was on the doorstep. Right. So, you’re out of the Army, what did you do then?

CW: Continued my training as a compositor for, er, six months before I was fully qualified, worked at two or three printing offices before joining the News, Chronicle and Star newspapers.

CB: And how long did you work there or what did you do there? Did you always do compositing or did you do something different later?

CW: I was a Lerner type operator and I —

CB: Which is a type of printing machine.

CW: Yes, it does the metal from which you print the newspaper from and, um, I did this and until such time as the owner of the News, Chronicle and Star decided to sell the newspaper and we were made redundant. From there I went on to the Daily Mirror as a Lerner type operator until such time photo composition came in. And I’d done some teaching at the London College of Printing and kept up with technology so I knew a little bit about this. So I was one of twenty people who were training the rest of the staff at the Daily Mirror in the new technology, um, until such time everybody was trained up and they employed another hundred people while we trained them and then when these, they’d all been trained they asked for vol— volunteers for redundancy so I retired two years early.

CB: And in retirement what have you been doing?

CW: In retirement [laugh] we bought —

CB: Well, its some thirty years ago.

CW: We then bought another nine and a half acre smallholding [laugh] which was basically to help our two sons out. They bought a business with agriculture machine and they had nowhere to store it so we decided this, this [cough] could be where they could store it but we didn’t bargain on nine and half acres with thirteen triple-span greenhouses [laugh] so, so we worked there, we filled these with strawberries which was a nightmare because, um, we had to employ many people, picking strawberries, and because they were in greenhouses they had to be very careful they didn’t touch the strawberries themselves. They had to pick them by the stalk and, of course, we had to employ all sorts of people and this went on until such time as the Ministry of Agriculture asked us to do, to do an experiment with a new variety they’d brought in from Holland. So, they supplied us with the plants for a whole greenhouse and these we grew until such time they were ready for harvest and, er, Margaret went out one day and these nice looking strawberries were all flopped and this was vine weevil. They’d got into the plants and as they — it spread so quickly everywhere we had to have the whole of the greenhouses sterilised and, um, and then we, then we went over to the production of asparagus. We filled them with asparagus.

CB: Less temperamental.

CW: [slight laugh] And didn’t need so many people to harvest.

CB: Yeah. Right.

MW: We did that for twenty, twenty-seven years.

CB: So asparagus worked as well as a good earner.

MW: Oh yes.

CW: Well, because it was early we got it in early in the greenhouses it commanded a good price and we took it, had it shipped down to Convent garden

MW: And Spittalfields.

CW: Yeah and one day, um, the wholesaler phoned up and said, ‘That lot you sent today, we want the same lot tomorrow. It’s going to the, um, the Queen’s banquet when Lech Walesa comes over.’ [laugh] Which was rather —

CB: All the way from Poland.

CW: Yeah.

CB: Gosh. Right. What did you do? Did you sell it or the kids ran it?

CW: Well, we ran it until — how long ago is it? Ten years ago now?

MW: Ten, yes.

CW: And then we sold it and retired.

CB: Aged eighty-six. Yes. Very good. We’ll stop there a mo. [pause] So, we’ve talked about the fact that when you were in the war your unit was quite separate from anyone else so there wasn’t a temptation to get into conversations with other units [clears throat] about what you did. But after the war, we’re now in civilian life, people tend to be nosy. To what extent did the, er, history of your experiences in the war come up in conversation and how did you avoid indicating anything about SOE?

CW: By and large for myself because I done quite a bit in the army proper, as it were, I could say what there was to be told about that and keep quiet about SOE.

CB: But did you have to be on your guard all the time?

CW: Not much. I don’t remember people, you know, delving deep about these things at all.

CB: No. So, why didn’t people talk about their experiences in the war?

CW: I think they were just happy that the war was over —

MW: And they wanted to forget it.

CW: They’d had a tough time, er, rationing was still in being. So I think they were just happy to get on with their lives and rebuild the —

MW: And we, we started a family straight away didn’t we?

CW: Yes.

MW: And you just put the rest all behind you. I mean they, they like, they like the fact now that we have kept records and they’ve got it all down now.

CB: Yeah, but in the earlier time when children are younger children have a huge curiosity so to what extent did they try to prompt you to tell you, tell them.

CW: I don’t remember them ever asking about the war. It’s not until you get into the teens or older that people begin to enquire.

CB: So at what stage do you think it was the wraps came off and you were about to talk about SOE freely.

CW: Well, it was after sixty years.

MW: Yeah. Once there started being publications. I mean I’ve got, I’ve got one that’s got my —

CW: Photograph in, yeah.

MW: Yeah, one, er, that the FANY officer did. The book “In Obedience To Instructions” is the title of the book, um, and the other girl who was at university [background noise] who got, got us to supply her with information. And I mean in the thing, you know, they put at the back, people that have contributed information —

CB: The credits at the back

MW: But that was well, well on.

CB: We’re talking about the ‘90s?

CB: Before the sixty years were up, um, certain publications began coming out by the higher ups more than we did. [background noise]

CB: Yeah, OK. Right. Thank you. So, after talking with Charles we’ll move to Margaret —

MW: Yeah, I’m going to move out to the bathroom, OK?

CB: That’s alright. What was the thing that was most memorable in what you did then Charles?

CW: [slight laugh] A message from Mr Churchill to his son Randolph, who was in Yugoslavia, to say, ‘Congratulations on your birthday’ [laugh] and one going back the other way from Randolph to Mr Churchill saying, ‘Congratulations on your last speech.’ [laugh]

CB: Which you could take how you like. [laugh]

MW: When you got the phone call from, from Gubbins you didn’t know it was him.

CB: And the other, other funny one, yeah — Gubbins being the top man.

CW: Top man in SOE.

CB: Yeah.

CW: In Algiers I was on duty, on night duty, and the phone rang and I picked up the receiver, ‘Will you come down to villa number so-and-so?’ I can’t remember the number. ‘I’ve got an urgent message for London.’ ‘I’ll send someone down,’ I said. ‘You’ll come down yourself.’ Bang went the phone [laugh]. When I got down there [laugh] it was Colonel Gubbins, head of —

CB: And you didn’t know he’d come there?

CW: Didn’t even know he was on the camp.

CB: Such was the secrecy of what you did that nobody knew who was anywhere I suppose.

CW: Obviously he’d been the Cairo.

CB: And he was on his way back.

CB: One final thing, did you have a code name?

CW: No but agents did.

CB: Right. Now we are going to talk with Mary, er, Margaret about her experiences. Now Margaret started earlier on. Can you start with the earliest recollections you’ve got and how you came to join the FANY and SOE?

MW: Right, er, I was born in Southfields, South West 18, in London, and went to the local school and eventually progressed Greycoat Hospital Girl’s School in Westminster. The present Prime Minister’s daughter goes there now. All the girls in our family went to Greycoat Hospital. When the war broke out I was fifteen and I was on holiday with my mother in Ireland. My father was head of Ministry of Pensions and because of the threat of bombing if the war started they’d already evacuated up to Blackpool. My father contacted us and said under no circumstances were we to return to our home in London. We had to come straight to him in Blackpool, which we did. My father had always wanted one of the family to be a civil servant and he was delighted when he was able to get me a job as a part-time civil servant, the lowest grade there was, so low that it is recorded in Hansard that I earned thirteen shillings and sixpence per week less four pence for a stamp. It became very evidence that the landlady looking after these civil servants who’d moved up there was not keen on housing relatives as well, so we were able to persuade my father to let us go back to London, on condition that we moved out if bombing got serious. So this we did and I did one or two jobs. I think one was with a printing firm and then, er, I was just coming back from work and the sirens were going. I was on my bike and I got back in, quickly got under the stairs with my mother and a friend and the house began to shake and, er, the next thing we knew, or discovered afterwards, a land mine had fallen in the street backing onto us and blown out our back door etcetera. So, as we promised my father, we moved out to Leatherhead and the old, what would have been the old Hoover company there was being used as a, as an arms, you know, what do you call it? For making arms and I had to test the strength of shells. A most boring job.

CB: This is an ordinance factory?

MW: Yes, whatever it was called, um, but I also helped at the, what had been a blind school normally in peace time but it had been taken over from one of the London hospitals that were being cared for, mostly diabetic children, and I enjoyed the work there and I, I admired the way the, the si— the sisters, the ward sisters, cared for people and I began to think this is something I would like to do. At sixteen I was allowed to get a job at Epsom, er, in a hospital there but I was longing for the day when I was eighteen and could start training properly. Unbeknown to me, my mother who hated being on her own had gone off to Guildford RAF Recruiting Office and said she would like to join the WAAF but knew she was over age but the officer there, the recruiting officer said, ‘Well, you don’t look over forty so you won’t have to give me a birth certificate. Just fill in this form.’ When my mother looked at the form, my brother who was nine years older than me was al— already a Fleet Air Arm pilot, my sister, six years older than me, was in a res— reserved occupation as a qualified physiotherapist and English teacher. So my mother realised that the mathematics didn’t add up, that this was possible, if she put their ages in. And the officer said just put in ‘of age’ for your more older children and put my true age which she did because she didn’t want to stop me from doing what I wanted to do, was do full training as a nurse in London. So, that was her off, off into into the WAAFs and she knew she couldn’t at all attempt an, an officer’s post because she’d have to produce her birth certificate. She did her square bashing funnily enough at Fleetwood which was just next door to where my father had got his Ministry of Pensions job in Blackpool. I did a year’s training and was on, put on skin ward and as a result of that, handling ointments and various medication, my hands both broke out in bad eczema so I was given six, I was given a month’s sick leave and when I got back they said, ‘We’ll put you on the wing, the where you don’t have to do scrubbing up and what have you, diabetic wing.’ That’s it. And, er, within a month it was all back again so they said, ‘Well, we’re very, very sorry but I’m afraid you’re going to have to finish your training. We can’t keep you on.’ So, I rang a friend who I knew had to give up and I said, ‘What am I going to do? I won’t get through the medicals for Army, Navy, Air Force, I’m no good for the land army and I don’t want to have to finish in a munitions factory after what I’d had to do with these wretched shells. So she said, ‘Go to this address in Baker Street. I can’t tell you any more but you won’t have a problem.’ So, along I went and the first thing they said to me was, ‘Well before we can talk to you need to sign the Official Secrets Act and you will be bound from conveying anything that you’re told here. You won’t be able to speak about it.’ So, I thought, ‘Oh gracious, what have I got ahead of me here?’ So, I did that and then had an interview and they said, ‘Well it will mean we think you’ll make a good wireless operator but it does mean joining the FANYs which is the First Aid Nurses Yeomanry.’ So I went along with all this so went to Henley to train with Morse code and after some months the sergeant came in and said, ‘They want volunteers for overseas. I’ve got forms here. Put your hand up if you’re interested.’ So I stuck my hand up and he said, ‘If you’re under twenty-one you must have parental consent you know, I’ve got the forms here for you if you want them.’ I then wrote a letter to my father, um, not thinking, you know, it was anything special, just to say, ‘Please can you sign the enclosed form? I want to go overseas.’ It was a time when all the troop ships were being torpedoed in the Med and yet, bless him, he agreed to sign it. Then, um, I’m trying to think what happened then. Yes, I — I’ve just written all about this to the — do you want to see?

CB: We’ll just stop for a mo. [background noise]

CW: An account I’d written of my embarkation and I thought the FANYs might be interested in it because the so-called colonel had taken over the, all of the other information. I had this embarkation letter and it’s amusing reading it all. I mean I don’t know if this would be useful.

CB: That would be useful. Just keep rolling. Can you tell us please?

CW: So, this was all about the embarkation and a disguised description of how we got to Liverpool and got on the dock and most of the group went off somewhere but another girl and myself were put in charge of the luggage. And we were standing on the port side and the troops all up on the ship. I never realised how big the ship would be and it was the Monarch or Bermuda (I’m allowed to say that now). And the chaps on board were throwing pens down, pens, pennies down to us and my friend and I were gathering all these up and luckily found a Salvation Army chap we were able to hand them over to. And then once our luggage was dealt with we were able to join the others and go on board and that was when the next thing we knew we were in Algiers.

CB: OK. So on the boat you’ve got lots of people, literally thousands?

MW: Yes the FANYs were allocated some very nice accommodation, about ten in a cabin. There was a little bit of controversy with the Queen Alexandra nurses, who thought we were in their cabin and they were in ours, but we got that sorted out. I was absolutely amazed when we went for our first meal to see beautiful white cloths and white bread which I hadn’t ever seen for years with rationing and the way you couldn’t have white bread in England and when we had time to go round the ship I was horrified to see how all the ordinary soldiers just had to sleep on, on slings just tied up.

CB: Hammocks.

MW: Mm?

CB: Hammocks.

MW: And we were in complete luxury really. I got a top bunk with a porthole window beside it and, you know, we just enjoyed the journey really.

CB: So you’re on the boat and you find yourselves —

MW: We arrived at Algiers and we were transported to this wonderful camp, if you can call it a camp, it was a long expanse of lovely sand dunes, right adjacent to the Mediterranean, which had been a holiday place for French people with these beautiful —

CW: Villas.

MW: Villas, um, dotted all along it. So about six of us shared a villa where we could just run out of the front of it, straight into the water. We were even able to swim on Christmas Day which was wonderful. And that side of things was fine. We had a team of wireless operators like myself and we used to work on schedules, day and night schedules. I hated the night schedules because when you wanted to get back to your bungalow at night in the pitch darkness you’d got troops patrolling all the time and most of them were, were troops that that been, were found they couldn’t cope with the sev— severity with actual fighting so I was always afraid that one of them would suddenly turn round and think I was an enemy approaching. Other than that I think was all quite straightforward. There was these dinner dances that the sergeants’ mess ran and that’s where I came in contact with my husband Chas. The —we were supposed to have meet with the officers’ mess but we found the sergeants’ mess a far more lively place to be and we worked on our schedules and you had to be very, very carefully because the Germans were always trying to van— to jam the air lines and you’d got to be careful that you listened intently so that you didn’t make mistakes and avoid asking the agent to repeat anything. And one strong rule was that if ever you were on the air and — contacting an agent and he put in Q U G IKAK, which in ordinary language, is ‘I’m in imminent danger, close down.’ And you weren’t allowed to put another pip on your key and then the rule was for weeks and weeks afterwards you still kept trying to contact the due schedules for that agent in the hope that he hadn’t been —

CB: Compromised one way or the other.

MW: And I was delighted the once it happened to me, it was about six weeks later the agent came up in his due schedule, his or her, because we never knew whether it was a man or woman that we were contacting.

CB: And what country was he in?

MW: In, in France.

CB: He was in France. Right, OK. So, all of yours were in France at that time?

MW: Yes.

CB: Not Italy?

MW: Not so far as I was aware.

CB: No. OK. So, just taking a step back, when you were in the FANYs what rank were you and how did the promotion go?

MW: You just went in straight away as a cadet ensign.

CB: You did, right. And would you like to describe what is an ensign is in those days?

MW: I haven’t a clue.

CB: It’s an officer’s rank isn’t it?

MW: Mm?

CB: It’s a woman officer rank.

MW: Nobody every explained it to us. That was what we were and that was it.

CB: OK.

MW: The actual bases which is just out of Bari.

CB: So, you’re in Massingham and you’re there for how long?

MW: A year.

CB: And then what?

MW: And then transferred to Italy.

CB: And what did you di there?

MW: Carried on the same way, sending and receiving messages.

CB: Where were the agents of yours then?

MW: They could have been anywhere. They could have been in Italy. They could have been in Yugoslavia?

CB: But not France?

MW: I think we, had we finished in — you’d better switch off.

CB: So, in your perception Mary you’re dealing with, as a radio operator, which is different from doing the other side that Charles was doing, so the agents you, you saw them did you at Massingham before they went?

MW: Yes, you know, they had all the agents there obviously.

CB: And they, when they then went from Massingham to the airfield, which was where?

CW: Blida.

CB: Blida and then they were flown. Do you know what planes they were flow in?

MW: No idea.

CW: No. We were never told.

CB: The security worked so tightly you didn’t know the simple steps because that would compromise what was happening?

MW: We knew that some of them were going over in our little subs and going ashore there.

CB: And the others were parachuted in?

MW: Yes.

CW: And the arms and ammunition and uniforms and things were done up in containers and dropped from Blida.

CB: That was done separately was it?

CW: Yep.

CB: So you would know what the signals were. Were you telling them, when you were doing the radio part?

MW: Well this was the part that was disappointing in a way because he knew what the message was but it didn’t mean a thing to the wireless operator so you’ve no idea what message you’re sending them.

CB: No. So you got the boring message which is vital but Charles has got the detail which is being coded?

CW: Yes. The recognition signals, the coordinates where you dropped he agent or supplies or what have you. Yes it was all —

CB: Yes and how did you make contact with the agents yourself Margaret?

MW: Well, by schedule. You were given a schedule, at a certain time you were given a code that you’d got to put in, you know, in Morse code to make contact with that agent and what to expect.

CB: And you’d wait for a reply would you?

MW: Reply, yes.

CB: Was it like the nine o’clock news or did the contact time change? So, what I’m saying is did you always contact the agent, each agent, at the same time or would it vary?

MW: I think it varied but we, you know, were told what the schedule was, what time we were supposed to be on to that person.

CB: Right. How often did you meet agents yourself?

MW: Well, they were around all the time at Massingham weren’t they?

CW: I never met any personally.

MW: Not to talk to did we?

CW: There were a lot trained on the camp but they were all separate, you know, we never got —

CB: So on the camp there were cells effectively cells of operation was there, so there was just to do with radio, one that was to do with cipher, different hats?

CW: Well, it was a radio station, you know, the, they all worked together, you know, on the thing but the agents were trained there and I never got contact with any of the agents. I just knew they were being trained.

CB: What nationalities were the agents Mary, Margaret, sorry?

MW: All sorts weren’t they Chas? Very difficult to know.

CW: Well, a lot were English, French-speaking English. Men and women. French people as well. One, a special one was an Indian, Khan, he was —

CB: Khan is a famous one actually, isn’t he? Yes, yeah, right, OK. So, after Italy, so you’re there in 1944 and ‘45, what happened when the war stopped? Where did you go from Italy?

MW: In, in Italy I, it’s again quite a comical thing, family thing, that my father had always said, ‘By the time you’re twenty-one they’ll be nothing left for you to do.’ What it turned out to be on my twenty-first birthday we were due to fly up to Sienna up to the north of Italy, um, a group of us, and there was fog and problems. So, the plane couldn’t take off so we had to go back to our billets and try again the next day and I thought well now my father can’t say there was nothing left for me to do when I was twenty-one because that was my first trip in an aeroplane. When we got to Sienna there was very little, um, messaging going on. We were just pursuing hobbies and needlework and various things to pass the time until, of course, the end of the war came. During that time I was in Sienna obviously I was missing Charles very much so I got some leave and I did a hitchhike down to Naples, stayed at the YWCA overnight, and then asked them where I ought to get a vehicle to take me across the mountains to Bari and they said, ‘Well, go to this filling station, get an American or a British truck. Whatever you do don’t get on an Italian truck and you must be mobile by 10 o’clock otherwise you won’t be over the mountains before dark.’ It got to 10 o’clock and no American or British truck had come in and I thought when you’re twenty in those days you didn’t know the sort of things that go on now. I thought, ‘Oh blow it. I’ll chance an Italian truck.’ I was sitting up between these two Italians driving up the mountainside where the drop was absolutely sheer on the right and if it went over it would be completely down the bottom and we got flagged down by an American despatch rider and he was horrified when I got out the cab. ‘What on earth are you doing there?’ ‘It was the only vehicle I could get.’ And so, he immediately flagged down an American jeep that had got one soldier in it and said, ‘Where are you going?’ And he said, ‘Right down the toe of Italy.’ ‘Well then in that case can you take this young lady? She wants to go to Bari.’ And I got in there as happy as Larry.

CW: But he flagged it down because it was badly loaded.

MW: Yes, the — that’s why he flagged the lorry down because he said any minute he could go down the mountainside because it was so badly loaded so obviously that’s why they told me not to get in an Italian truck.

CB: Fascinating. So, when did you learn about your demob?

MW: When we were up in Sienna. It was sort of November-time wasn’t it, when —

CB: November ‘45.

MW: Yeah, and there again he was very crafty, my husband. He got some leave and came up to officially in quotes “see me off” and he got very friendly with our commandant, and he duly shook hands with her and said, ‘Goodbye.’ And away we went. At our first comfort stop who should bail out of the luggage truck was Charles. So that we had another evening in Naples before I embarked for home.

CB: Fantastic and from Naples did you take a boat?

MW: Yes.

CB: Where did that go? Marseille, Southern France, was it?

MW: Yeah. Must have done. I can’t remember where it went,, I just knew i was going home.

CW: It was home back to England.

CB: When you got back to England then what?

MW: Well, then I went back to Southfields, to where my mother and father’s home was and waited, got the — oh, that’s another thing. I did get a job there while I was getting ready for the wedding. We were going to get married as soon as he got back and I took a job in a day nursery, looking after little toddlers, and the cook there was a very ample lady. She said, ‘I hope your husband’s got a good job because you won’t manage on less than ten pound a week.’ And I thought, ‘Horrors, he’s got his, his apprenticeship to finish. There’s no way he’s going to get ten pounds a week and he’s got to get to Dartford every day from Southfields.’ But I didn’t dare tell anybody that there was no way going to afford it. But we managed, didn’t we? We got all sorts of second hand stuff and we got though.

CB: So how long did your job going on for or it didn’t last?

MW: Oh once we were married because we wanted a family.

CB: And your mother came out of the RAF?

MW: Oh she came out. She did about three years I think but as I say all the different officers she worked with said you ought to ask for a —

CW: Commission.

MW: Yeah but she didn’t because she knew she’d have to find her birth certificate. We were crazy.

CB: Right. What would you say would be your most memorable point of your service in the SOE?

MW: I don’t know that there was — I suppose the most memorable point was that we knew, I knew, we were going to go where he’d gone.

CB: To Bari.

MW: Yeah. That was the highlight.

CW: Yes because I, having supposedly gone to gone to Yugoslavia, I was in Bari and I wrote to her that I was in Bari and not Yugoslavia. [laugh]

CB: Right. So that made you feel better.

MW: Yeah.

CB: Right. So, we’re back talking with Charles a bit more about the delivery of agents into places like France. So, how do did that work then?

CW: Hughenden Manor worked — did maps for the pilots, detailed maps for the pilots, as to where they had to go to, which was absolutely brilliant, and this went on all through the war.

CB: And, er, the pilots that delivered, this is where they’d land but not just that but it’s where they were parachuting dropping as well?

CW: Yeah parachute drops and dropping agents and dropping agents up, not only dropping agents, Government people as well.

CB: Oh were they? Yeah. Any prisoners?

CW: No. I don’t think they brought any prisoners back as far as I know.

MW: But they brought agents back didn’t they? Picked up people as well as dropping humans.

CB: Yeah, and what was the major activity really of the, of flying people? Was the delivery of arms, ammunition and stores in general pretty busy?

CW: It, it was especially in the last bit of the war where —

CB: From D-Day.

CW: Yeah, where the Mace [?], yeah after D-day the Maces [?] were all organised and armed and used to delay German troops coming up to the coast.

CB: Right, so doing you cryptography, your coding, then you were seeing all the instructions?

CW: Yes. Yes.

CB: And the detail must have been quite fine in terms of finding the places?

CW: Yes it was all coordinates for exactly where they were but really and truly it didn’t mean anything unless you’d got a map where you could sort it all out but we didn’t have the opportunity.

CB: Right. Good

CW: I was born in Yorkshire in a mining village and, um, eventually went to school at, a grammar school, and eventually I — there was no, very much work around up there but eventually an uncle and aunt came to visit us, who lived in Dartford in Kent, and they said where he worked it was a printing firm in Dartford, and where he worked they needed an apprentice, and I was fifteen at the time and they said if I would like to I could come and live with them and be trained as a compositor. So, I jumped at the chance and so I moved down to Dartford in Kent and, er, was being trained as a compositor. When the war clouds were gathering around, er, the Government decided that twenty-year-olds would be called up and trained ready for war and I received papers to join the Royal Artillery on Salisbury Plains but before the due date to report I was — war was declared — and I was called up to the London Irish Rifles and had to report to a station in London and, um, reported there. From there, from there we then trained onto the London Underground and taken to Southfield Station in South West London, um, marched down the road to Barkers Sports Ground, next to Wimbledon Tennis courts, where we were to do all our square bashing and training. And this happened for several weeks, er, before we were fully trained and then from then on we were stationed in many parts in England, various places, and eventually the battalion was training new recruits to go and be transferred out to other units and, um, I got fed up with the repetition that this was giving us [slight laugh] and by that time the Bat— the Battle of Britain had started and they were running short of pilots so they said they’d like volunteers from the Army to join the Air Force, so I volunteered. I was taken down to London, interviewed and passed all the tests and they said, ‘We’ll train you as a pilot. Go back to your unit and then you’ll hear from us.’ Having got back to my unit the, um, we was — then a few weeks later I — they stopped all transfers to the Air Force. We were taken up to Scotland to join a special unit being formed of tanks and artillery. This was prior to being shipped out to North Africa. So we went out to North Africa and landed at Algiers. From there we moved forward up into Tunisia where we had over a year of fighting the Germans in North Africa. It was quite a horrendous time really. We lost quite a few of our people and I have been out since to visit the graves of three of my men that got killed out there. And then, stop, I don’t know where I’ve got to.

CB: So we’ve talked about Charles joining in 1940. Then he moved around a lot he said. What, what were you doing in that time specifically?

CW: We were doing guard duty on airfields and RAF records office and things like that. I distinctly remember my twenty-first birthday was on guard duty at the RAF offices in the snow [laugh] and, er, after that we were training up people being drafted in to us and then once they were trained they were drafted out to other units. And this was getting too boring so I volunteered for the RAF and got accepted and, having got accepted, they then decided that our unit would join a special unit being assembled in Scotland ready to go out to North Africa of tanks and artillery.

CB: So which year are we in now?

CW: That’s 1942.

CB: Right. Operation Torch.

CW: Yes.

CB: Right, OK. And where did you land?

CW: We landed in Algiers. It was a troop carrier just in, in the port in Algiers. We were then trained and taken up the coast to towards Tunisia where we were then taken into the mountains, er, as a defence ready for attacking the Germans.

CB: And were you at this stage on tanks or were you on anti-tank weapons or what were you doing, infantry?

CW: We didn’t see the tanks in, on that occasion apart from on the plain, the Gudlat [?] plain in front of us. You could see the tanks moving but we were stationary until we did an attack one day on hill 286 and, um, we had we had to move from our position in broad daylight to get into positon to start an attack the next morning at dawn and this was in full view of the enemy and I said to my people, ‘As soon as we get in the middle of this area we’re gonna — all hell will break loose. We shall be bombed.’ Which we were and the only casualty we had was our platoon commander got shrapnel in his back and we eventually dropped into a wadi, which I thought would be quite safe, and we moved down this wadi and — to get to the position where we would form up for the attack the next morning. And, er, moving down this wadi what I heard from nowhere, I don’t understand where it came from, which is probably my guardian angel, one word which said, ‘Run.’ So I shouted to my chaps, ‘Come on!’ Ran down the wadi, turned the bend and no sooner got round the bend then a shell fell right in the wadi, injured three of my people. I went back, patched them up as best I could and stayed with them until the stretcher bearers came, er, then continued on to do the attack the following morning. The following morning we did this attack, um, because we’d lost our platoon commander the, the other two platoons were in advance and we were in reserve and we went over the hill and nothing happened; over the second hill, nothing happened; over the third hill and all hell broke loose and they, they were just machine-gunned. We lost about seventy-five per cent of our personnel during that battle [sniff] and then we were formed up in, dropped into the wadi again, for protection, stayed there overnight but at dawn the next morning there was a counter attack, so we just had to get out of it and, er, we all retreated and after that battle we were rested, er, and [sniff] can you stop a minute? [background noise]

CB: Right, we’re just getting a bit more detail on this [clears throat].

CW: When the attack went in and the two platoons in front were machine-gunned, um, the rest of us were left in a large depression in the ground being shelled and I suddenly discovered with us was a, a Royal Artillery observation officer with a wireless set and he, he ordered me to the top of the hill to find out where the gun was firing from. So, off I went to the top of the hill, saw that it was coming from a farmhouse down on the plain, got back to where our positon was and found out a shell had dropped exactly where I had been lying.

CB: Wow.

CW: So, um, that was —

MW: Smokescreen.

CW: Yeah. He then ordered a smokescreen and we were then able to get back to the wadi and then —

CB: He got his guns to fire a smokescreen?

CW: Yeah. He radioed back and got the guns to put a smokescreen down so that we could get out. So, off we went and back to this wadi and from the wadi we had the counter-attack. So we had to retreat and reform up eventually with only twenty-five per cent of the battalion.

CB: Amazing. OK. So then you rested a bit, then what?

CW: We, we were rested and re-enforced and we did an exercise, which was a ten mile march and, er, did a mock attack of house clearing, during which I banged a knee, which had been damaged in football previously, which began to swell and we did a ten mile walk, marched back and half way back I was limping with this knee problem. The CO drew up in a truck beside me and said, ‘What’s your trouble?’ [slight laugh] And I said, ‘I just banged it and, you know, it’s swollen up.’ He said, ‘On the truck. Report sick when you get back.’ Which I did and, er, we had hot and cold compresses and [unclear] on it, which had no effect whatsoever and eventually they said, ‘Well, you’re no good to be infantry. We’ll have to down-grade you.’ So, from being A1 I was downgraded to B1, sent back to a transit camp at Philippeville. There with — I couldn’t walk about because it was painful, I had nothing to read and it was so boring [slight laugh] I was just going mad. I then was transferred to another transit camp at Algiers, just outside Algiers, and same thing, nothing happening, nobody took any notice of us. We just stagnated there until one day on the notice board there came a notice to say that an education unit would be arriving and anybody could volunteer and they would try and find you something to do. So, I was top of the list and they came. Education test in the morning: English, maths, geometry [?], starting from the simplest and going up as far as you can, even Pythagoras and beyond if you could. And whilst they marked the papers in the afternoon they would give us a mechanical aptitude test. They threw you a locking piece and said, ‘Put that together and then you’re going for an interview.’ And, um, the officer said to me, ‘What would you like to do?’ And I said, ‘I’d heard they were starting an Army newspaper in Algiers and I was a compositor. I would go on the army newspaper.’ And he just laughed and said, ‘I don’t think there’s not much chance of that. What else would you like to do?’ So I said, ‘I don’t care as long as I do something. I’m going mad just doing nothing.’ He said, ‘I think you’d make a good cipher operator’. I said, ‘Suits me.’ [slight laugh] A week later I’m called into the office and given a move— moving order. There were six of us on this moving order and I walked outside, quickly looked to see where we were going to — no destination. So I shot into the office and said, ‘There’s no destination on here.’ ‘You’re being picked up,’ he said. So, the driver came and I said, ‘Where are we going?’ And he said, ‘I’m not allowed to tell you.’ [laugh] So, I wondered what I’d landed myself in for. Off we went in the truck and the other side of Algiers it was a, a large holiday home complex built on the sands, villas all on the sands, being surrounded by barbed wire, guards on the gate, and in we went. Going inside there was Army, Navy, Air Force, civilians, and everybody including girls [augh] and this was a radio station which was — belonged to SOE, working to the agents in France and Italy and Yugoslavia. There I was trained as a cipher operator and worked there for quite — a year, worked there for a year. During that time the sergeants’ mess decided that for entertainment we would do dinner dances about every fortnight and invite the FANY girls who were on the camp. They were radio operators and secretaries and, um, there we had these dinner dances. I teamed up with a Margaret, a different Margaret, I teamed up with a Margaret as a dancing partner until such time she went on leave and then I teamed up with Margaret, who’s now my wife, and we had a year working together on the same camp until such time I got a moving order to say I had to go to Yugoslavia. We exchanged addresses and said, ‘If you’re my way pop in, you know, it would be good to see you.’ And, er, off I went to the airport. We had to fly to Bari, then down to Taranto and then get the boat over to Yugoslavia. Having got to the airport there was the most violent thunderstorm. The plane couldn’t take off so a twenty-four-hour delay. Took off the next night. Halfway across the Med, er, one of the twin engine, one of the engines of this twin engine Dakota, started misfiring so the pilot said, ‘We’ll never make it over the mountains to Bari. We’ll have to land Naples.’ So, down we went to Naples, another delay. Eventually we got to Bari, walked into the office in Bari and they said, ‘Oh, sorry. We’ve sent people from here to Yugoslavia. You’ll have to take their place here.’ So, er, settled in at Bari. So, a month later I’m de-ciphering a message which said the following FANYs will be joining your unit so I quickly looked down and fou— found Margaret Pratt was on the list. And I quickly made contact with Margaret and we had another year together in Torre al Mare, just below Bari, in Italy. There we got engaged. Can you stop there?

CB: So, we’ve talked about you being in Algiers and then going to Bari in Italy. At this time you’re a trained cipher operator but what exactly did a cipher operator do?

CW: He made plain language into codes which could be transmitted by wireless and we started off with the agent had, um, a book, a book and we had to copy exactly the same and they, um, used pages and lines and the number of words in the line on squared paper. And then the A in the line was numbered 1 and second A, 2 and all through the alphabet. So we had numbers on top of the lines and then you read down and wrote across for a second identical one. So it’s a double transposition and, um, this was then transmitted by wireless and the agent could reverse the process the other end to get the plain language out but it had to be exactly right because if they made a mistake or if you made a mistake it was indecipherable. So, we had a number of indec— indecipherables obviously and when we weren’t busy with doing traffic at the time we had to work on the indecipherables to see — and we got to know that some agents did certain things so we could remember and do exactly the same to get them back to plain language. And then eventually we moved on to one-time pads which were figures, er, which were just ad-lib figures, you know, nothing about them. So, you had a one-time pad and the agent had a one-time pad and they had theirs on silk, printed on silk, which was easily got rid of if, er, if they had to if they were captured.

CB: So, here we are in a situation where you’re in the home station and the agent is, in this case, Yugoslavia, how did they get out there, the agents, and the, other staff?

CW: They had submarines and boats, um, which went across at night and this is one of the things that we decipherers had to send the night recognition signals and the places where they were going to be landed so that was — and if, if they didn’t get the recognition signals by flashlight they would— they wouldn’t row ashore.

CB: Right, and to which extent were aircraft used in this job from Italy?

CW: They, they were used as well to drop agents in, er, mostly dropping them rather than landing them. All the landing I think was done by sea.

CB: So, would they take any equipment with them or would that be a separate sortie in order to supply them?

CW: Mostly they took their wireless sets with them but, er, if they got damaged or anything we had to drop others by parachute.

CB: OK, and did they stay they all the time or were they plucked out every so often?

CW: They came back for reports occasionally.

CB: They did? Right. What was the survival rate like?

CW: We don’t know really because it never, the news never got to us.

CB: Right. I’ll just pause there a mo. It’s just worth stating here that this isn’t a regular Army operation, this is SOE, so you had a reporting line that wasn’t directly in the Army was it?

CW: No it wasn’t but before the SOE this is, I was on a football match, um, when we — after the North African campaign finished, um, on the touchline watching the football, and the CO came round and pulled me out and he said, ‘I understand they accepted you for training as a pilot two or three years ago?’ I said, ‘Yes, that’s right.’ He said, ‘They want to know if you’ll volunteer as a glider pilot.’ Which was obviously for the invasion of Sicily of Italy and I politely refused. I really didn’t fancy not having an engine with me.

CB: Yeah. Interesting so this is your CO? How did the rankings go? I mean, that was the same as a military rank but you were kept separate, same as an army rank.

CW: Well this is Army, before the SOE.

CB: This was before, sorry, right. So, now going to SOE, what, how were you categorised there in terms of — because you were separated, how did that work?

CW: We were still Army ranks and obtensibly in the Army, what they call it? Signals unit. The stations had various names. The one in Algiers was called ISU6 or Massingham. We had an air, an aerodrome at Blida, inland, where the dropping containers were filled for dropping in southern France.

CB: So, Massingham is the, the station code name for North Africa in Algiers?

CW: Yeah. That was the station called Massingham, yes.

CB: Yeah. So, was there a dedicated airfield for your people?

CW: Blida. Well it was at Blida but because it was so secret [slight laugh] it wasn’t, er, common knowledge. We also had a submarine in the harbour at Algiers.

CB: Oh did you?

CW: That went over to France and surfaced and rowed people ashore, yes.

CB: So, you were training people, were you? To go to Blida, the aircraft, Air Force station before being delivered or were they trained before they came to you?

CW: They were trained on the camp at Massingham.

CB: They were? Right. Yeah. And this is really for supplying France before you got, before the North African war finished, is that it?

CW: No, that’s after the war had finished.

CB: It had finished. OK, so when you went to Italy, to Bari, that was well after the invasion of Italy?

CW: Yes. The war was going up. Po valley was still a war zone, up in the Po valley.

CB: Right up in the north, yes, so they had capitulated anyway but we’re talking about 1944, are we?

CW: Yes that’s right. It was at the tail end of the war.

CB: OK, so how did it progress after this supply you were talking about, Yugoslavia. How long did that go on for and what happened afterwards?

CW: Well, that was quite involved because, um, you had Mihailović they backed to start with and eventually they moved over to Tito and —

CB: Mihailović was the loyalist, royalist? Yeah.

CW: I think most of the people were more concerned with what happened after the war rather than what was happening during the war.

CB: Right, so Tito was the communist and he was the one you were backing then?

CW: Yes, that’s right.

CB: OK, so we’ve come to — have come to the end, have we reached the end of the war yet or did you go somewhere after Bari?

CW: Yeah, when the war finished —

CB: What did you do?

CW: I did, er, a quick course on Typex machines, which is a keyboard, and then transferred to Athens where I spent a few months before being shipped home for demob.

CB: And what did you do in Athens?

CW: Well, basically enjoyed ourselves [laugh]. There was nothing much to do really. The war was over and we just had various messages to transmit, encipher and decipher but not many.

CB: Right, right. So, just going back a bit on the SOE front, the ordinary forces didn’t know about SOE?

CW: No.

CB: And how did you explain away that you were separated from them and why?

MW: We never mixed with them did we?

CW: Yeah. It didn’t occur. The only time we had any trouble really, if any of our people were picked up by the military police and then they were [laugh] had to be got out of gaol, as it were, by people from our camp, to go and say well, ‘These are our people. You’ll have to let them go.’

CB: But not knowing, not telling them why?

CW: Yes. ‘Cause the Unit said they didn’t know about ISSU6 and Force 399 and Force 133 —

CB: OK.

CW: All odd names they had.

CB: Yeah. So mentioning those, in sequence, what were they? So, ISSU6 iss MI6?

CW: ISSU6 was at Algiers but it was also called Massingham.

CB: Right. OK.

CW: And then going to Italy it was Force 399.

CB: Right. OK. Technically a signals unit as far as you were concerned?

CW: Yes.

CB: OK. Then what, what else were there in titles? What were you called when you went to Athens?

CW: I was back in the Army then. I was transferred from SOE back into the Army.

CB: Oh were you?

CW: After the war was over and trained on Typex machines and doing enciphering and deciphering for the Services.

CB: Right, so in the light of the fact the SOE was the “invisible force” you couldn’t talk about it. How did you assimilate back into the army without people tumbling to what you’d been doing?

CW: Nobody ever asked any questions, just assumed that I’d been transferred from a different army unit.

CB: Right. Right. OK. [background noise]

CW: Initially training on rifles.

CB: In the Army.

CW: In the Army on Rifles, Bren guns, and the PIAT, the projector [?] infantry anti-tank gun, but with the SOE there was no need to carry arms at all.

CB: So you went, after the end of the war in Europe, you returned, you reverted to the regular Army. Was that the point at which you did?

CW: Back, back into signals.

CB: VE, on VE Day.

CW: Yes.

CB: Right.

CW: Yes, into Signals and posted to Athens.

CB: Yeah, and what happened in Athens? Did you stay there right until your demob in 1946?

CW: Yes, I was demobbed from Athens, back to Taranto all the way up to Italy.

CB: By train.

CW: Up the French coast by train.

CB: Then after the war what did you do Charles?

CW: After the war, interestingly enough, um, I made straight for somewhere I’d only been once before which was Southfield Station, where I marched the other way down Wimbledon Park Road to where Margaret’s parents had a house [laugh] met her [laugh] and where we got married. So, having started the war there I ended it there.

CB: That’s where you met Margaret in the first place was it?

CW: No, Algiers. I met her in Algiers where I met her in the first place.

CB: Oh you didn’t meet her until then even though she was on the doorstep. Right. So, you’re out of the Army, what did you do then?

CW: Continued my training as a compositor for, er, six months before I was fully qualified, worked at two or three printing offices before joining the News, Chronicle and Star newspapers.

CB: And how long did you work there or what did you do there? Did you always do compositing or did you do something different later?

CW: I was a Lerner type operator and I —

CB: Which is a type of printing machine.

CW: Yes, it does the metal from which you print the newspaper from and, um, I did this and until such time as the owner of the News, Chronicle and Star decided to sell the newspaper and we were made redundant. From there I went on to the Daily Mirror as a Lerner type operator until such time photo composition came in. And I’d done some teaching at the London College of Printing and kept up with technology so I knew a little bit about this. So I was one of twenty people who were training the rest of the staff at the Daily Mirror in the new technology, um, until such time everybody was trained up and they employed another hundred people while we trained them and then when these, they’d all been trained they asked for vol— volunteers for redundancy so I retired two years early.

CB: And in retirement what have you been doing?

CW: In retirement [laugh] we bought —

CB: Well, its some thirty years ago.

CW: We then bought another nine and a half acre smallholding [laugh] which was basically to help our two sons out. They bought a business with agriculture machine and they had nowhere to store it so we decided this, this [cough] could be where they could store it but we didn’t bargain on nine and half acres with thirteen triple-span greenhouses [laugh] so, so we worked there, we filled these with strawberries which was a nightmare because, um, we had to employ many people, picking strawberries, and because they were in greenhouses they had to be very careful they didn’t touch the strawberries themselves. They had to pick them by the stalk and, of course, we had to employ all sorts of people and this went on until such time as the Ministry of Agriculture asked us to do, to do an experiment with a new variety they’d brought in from Holland. So, they supplied us with the plants for a whole greenhouse and these we grew until such time they were ready for harvest and, er, Margaret went out one day and these nice looking strawberries were all flopped and this was vine weevil. They’d got into the plants and as they — it spread so quickly everywhere we had to have the whole of the greenhouses sterilised and, um, and then we, then we went over to the production of asparagus. We filled them with asparagus.

CB: Less temperamental.

CW: [slight laugh] And didn’t need so many people to harvest.

CB: Yeah. Right.

MW: We did that for twenty, twenty-seven years.

CB: So asparagus worked as well as a good earner.

MW: Oh yes.

CW: Well, because it was early we got it in early in the greenhouses it commanded a good price and we took it, had it shipped down to Convent garden

MW: And Spittalfields.

CW: Yeah and one day, um, the wholesaler phoned up and said, ‘That lot you sent today, we want the same lot tomorrow. It’s going to the, um, the Queen’s banquet when Lech Walesa comes over.’ [laugh] Which was rather —

CB: All the way from Poland.

CW: Yeah.

CB: Gosh. Right. What did you do? Did you sell it or the kids ran it?

CW: Well, we ran it until — how long ago is it? Ten years ago now?

MW: Ten, yes.

CW: And then we sold it and retired.

CB: Aged eighty-six. Yes. Very good. We’ll stop there a mo. [pause] So, we’ve talked about the fact that when you were in the war your unit was quite separate from anyone else so there wasn’t a temptation to get into conversations with other units [clears throat] about what you did. But after the war, we’re now in civilian life, people tend to be nosy. To what extent did the, er, history of your experiences in the war come up in conversation and how did you avoid indicating anything about SOE?

CW: By and large for myself because I done quite a bit in the army proper, as it were, I could say what there was to be told about that and keep quiet about SOE.

CB: But did you have to be on your guard all the time?

CW: Not much. I don’t remember people, you know, delving deep about these things at all.

CB: No. So, why didn’t people talk about their experiences in the war?

CW: I think they were just happy that the war was over —

MW: And they wanted to forget it.

CW: They’d had a tough time, er, rationing was still in being. So I think they were just happy to get on with their lives and rebuild the —

MW: And we, we started a family straight away didn’t we?

CW: Yes.