Twenty Lancasters

Title

Twenty Lancasters

Description

Article by Carl Ollson from the Illustrated magazine published on 25 March 1944. The article covers the preparations made by the station staff to prepare the aircraft and equipment for an operation. There is a large photograph of twenty Lancasters in a group, together with some of their crews. There are pictures of the squadron bomb load on their trollies with the armourers, of the aircraft servicing tradesmen, the refuellers and drivers. Also included are the cameras and film magazines even the thermos flasks. The final picture is a full page in colour of Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris. On the reverse is part of an article about the entertainment provided for the American armed forces, part of a article about where the German armed forces were in Europe and an article about a farmers life during this period.

Date

1943-03-25

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Language

Format

Pages from a magazine

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

PThompsonKG15010058, PThompsonKG15010059, PThompsonKG15010060, PThompsonKG15010061, PThompsonKG15010062

Transcription

12 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944 13

[Photograph]

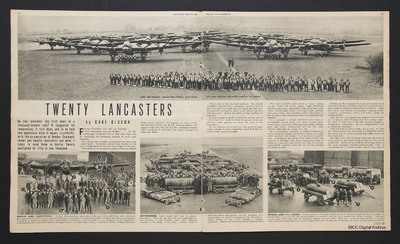

HERE ARE TWENTY LANCASTERS – TYPICAL RAID TURN OUT FOR THIS STATION – WITH SOME OF THE CREWS

TWENTY LANCASTERS

by CARL OLSSON

Do you remember the first news of a thousand bomber raid? It staggered the imagination. It still does, and so to help you appreciate what it means ILLUSTRATED, with the co-operation of Bomber Command, shows you twenty Lancasters and what it takes to send them to Berlin. Twenty multiplied by fifty is one thousand . . .

“FIFTEEN hundred ton raid on Leipzig” . . . “Two thousand tons on Berlin” . . . So the newspaper headlines run as, day after day, our air onslaught on Germany mounts in scale and intensity.

To a great many people, such figures are becoming – just figures. Symbols, scanned over briefly by the eye, a rough guide to the size and weight of the raid.

This story is an attempt to explain what lies behind those round numbers. To express, in terms of the life and work of just one R.A.F. bomber station, the nature of the toil, the cost and the prodigious human effort involved in reaching those plain tonnages of blast and flame.

[Photograph]

REPAIR AND INSPECTION. In this photograph are seen some of the men whose skill, drive and enthusiasm are responsible for getting the Lancasters back into commission in the shortest possible time after they have been damaged in attacks on important targets. Key to the numbers is as follows: 1. W.Os and N.C.Os; 2. Armourers; 3. W/T Mechanics; 4. Electricians and Instrument Makers; 5. Engine Fitters; 6. Spark Plug Testers; 7. Airframe Fitters; 8. Radio Mechanics

[Photograph]

ARMOURERS, bomb squad and load for twenty Lancasters. These are the men who are responsible for the servicing of the bombers with their offensive weapons in the shape of the giant “cookies” some of which are seen in this picture, and the incendiary containers which are used in conjunction with the high explosive bombs to add to the damage to military objectives. Officers and men have heavy responsibilities.

This is one of the war-built stations. Its aircraft strength is twenty-four Lancasters – £40,000 each as they are delivered, slick and new from the factories. Its personnel strength is about 2,500 officers and men and W.A.A.F. About one-tenth of that number are aircrews.

It costs £3,000 a week to feed the station and to clothe them all. And to clothe the ground staff and aircrews costs £40,000 – or about the cost of one Lancaster.

In the maintenance stores is a vast array of spare parts, enough to refit completely about half the aircraft on the station strength.

The stock includes such items as spare engines (£2,500 each), tail planes (£300), single Browning machine guns (£45), parachutes (£35), propellers (£350 each), turrets (£500 each), tyres (£50 each), wireless sets (£250 each), and countless other items down to rivets, screws and aluminium sheet for patching flak damage.

It is equipped to defend itself with such items as searchlights (£1,250 each), A.A. guns (£2,000 each), scout cars (£1,350 each), Bren guns (£35 each), tommy guns (£30 each), ammunition (£7 10s. for 1,000 rounds), grenades (4s. each), etc., etc.

It is a township, a factory, a battle headquarters and a front-line assault point from which men sally forth to attack the enemy. It is never at complete rest. Throughout the twenty-four hours of the day someone is working. Set down among the fields of home its 2,500 men and women can lead an entirely independent existence from the rest of the country for weeks on end.

If they are ill or injured they can get treatment in their own hospital. Canteens, kitchens and food stores big enough to supply a small town feed them. They have their own sources of recreation – playing fields, a cinema, sometimes a dance hall with a stage for variety shows.

And now let us visualise our station’s day’s work in a 2,000-ton raid scheduled for the coming night. Its share in that raid is the full station strength – twenty-four Lancasters. It is a long-distance raid to Southern Germany.

Take-off will be before dusk, say 5 p.m., so that the long journey out and home is completed before the moon rises or early morning fog settles down on the aerodrome.

By eight a.m. the handling crews will be hard at work down in the bomb dump at the far end of the aerodrome. Scores of men will be slithering about in the mud bringing hundred-pound-weight cases of incendiaries to a central section where they will be

[Photograph]

PETROL AND OIL CREWS. Motive power for our great bombers is by no means a simple matter to provide, for oil and petrol on a vast scale are required before a Lancaster sets out on a mission over enemy territory. And here you see some of the men and machines engaged on this work. They are: 1. Tractors and Drivers; 2. Oxygen trailer and Crew; 3. Salvage Crew; 4. Fire Tender Crew; 5. Oil Bowsers and their Crew; 6. Petrol Tankers and their Drivers

OVER

[page break]

14 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

TWENTY LANCASTERS – continued

packed into the special containers carried on the aircraft.

The men advance from the bomb dump in lines of ten; with the exception of the two end men, each man holds in either hand one handle of the incendiary case. Thus at each journey the men are carrying nine hundred pounds of bombs to the packing section.

In another part of the dump other men are rolling out the great 4,000-pound and 12,000-pound high explosive cookies and mounting them on to low engine-driven bomb trolleys. Others are loading flares. All this work goes on without a pause or break till the early afternoon when the trolleys are driven out to the aircraft. Lunch is a hastily eaten sandwich and a cup of tea.

Meanwhile in another section armament crews are working against time feeding tens of thousands of cartridges into the ammunition belts which will go to the gunners. Over the airfield at the tanks other men are filling the great 2,500-gallon capacity petrol bowsers and the oil bowsers, each of which holds 450 gallons.

One petrol bowser holds just enough petrol for filling one Lancaster if it is a long raiding journey. So many journeys must be made back and forth from the storage tanks to the aircraft waiting at the dispersal points. Again it is mid-afternoon before they are all filled.

At the dispersal points ground crews are swarming over the bombers in their charge. Every point in the bomber is being checked and re-checked: engines, plugs, instruments, guns, turrets, undercarriages, tyre pressures, bomb door mechanism and the host of other things. Some “snag” to one part or another of the bomber is nearly always found, and it has to be set right, with the toiling men always working against time.

If it is a fault connected with the flying ability of the aircraft it has to be set right in time for a test flight which must be made to make sure that the fault has been rectified long before take-off on the raid.

It sometimes happens that two or three test flights are made before the sweating ground crews have completed the job to the satisfaction of the captain of the aircraft.

Over at the sheds there is almost certain to be two or three bombers getting a special overhaul to put them into full serviceability at the hands of skilled maintenance crews and fitters. Perhaps whole engines may be changed, as a result of damage, patches fitted over flak holes, new instruments put in or pipe line and cables refitted.

Test flights are made in these cases, of course, and not infrequently the maintenance crews are working on the aircraft right up to a few minutes before take-off. Skilled crews have been known to refit a new engine within less than an hour before take-off. Which is certainly running it close.

While all this sweat and toil is going on in many

[Photograph]

LOADING FILM INTO MAGAZINES FOR AERIAL CAMERAS

[Photograph]

HERE ARE THE CAMERAS WHICH WILL BE USED ON THE NEXT BOMBING RAID BY THIS LANCASTER FORMATION

different parts of the airfield other special staffs are also working against time.

The intelligence officers are sweating on their filing systems getting out data about the target, getting out target maps and photographs, collecting information from Group Headquarters and from the pathfinder force engaged – all to be ready for the briefing of the crews which will take place by 2 p.m.

The meteorological officers are collecting and

[Photograph]

FLASK LOAD FOR TWENTY LANCASTERS – COUNT THEM

revising up-to-the-minute weather information from their own central channels.

In the locker rooms another staff is sorting out all the items of clothing and equipment which will be issued to each member of the air crews as soon as the briefing is over. About fifteen articles for each man ranging from life-saving waistcoats to socks.

In the kitchen Waafs are cutting sandwiches for nearly two hundred aircrew and parcelling up rations of chocolate, fruit, chewing gum and other items of refreshment.

In the station offices the Commander and other officers are selecting the crews and working out technical data for the journey. Sometimes news information comes through from group headquarters making a change of plan necessary.

It may happen that this change has to be made and most of the morning’s work altered within half an hour of the briefing.

The only people who have no part in this unceasing labour are the flying crews who will go on the raid.

Theirs, perhaps, is the worst part – the waiting from the time they are “warned” for a raid that night until the final take-off. A long wait which is broken only by the briefing and then by the dressing up in the crew room.

But everybody else on the station goes unceasingly and doggedly on until the moment comes when the last aircraft is signalled down the runway and off on its journey.

Then, and only then, do the tired ground crews, the bomb crews and the others stretch their aching limbs and take their ease in canteen or mess hall. But not for long; in an hour or so it is time for bed, to be ready for an early morning start and another long exhausting day.

[page break]

March 25, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 15

[photograph]

“HOW DID YOU DO?” AIR CHIEF MARSHAL SIR ARTHUR TRAVERS HARRIS, Air Officer Commanding in Chief, Bomber Command, gets the “gen” about the night’s big raid on Germany. His command has been called (by a neutral correspondent) the “Hammer of the Reich.” Because, for the first time since the days of Frederick the Great, the German people have been made to feel the wounds of war inside their own country. And it is the Bomber Command of the R.A.F. which has done it.

(Colour Portrait by James Jarché)

[page break]

16 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

THE WEHRMACHT AT ZERO HOUR

Where Hitler’s forces on land, on sea and in the air are awaiting attack

It was with a heavy heart that we tried to estimate the total strength of the Wehrmacht three years ago. Even a casual survey showed that the Germans had massed huge forces in the west of Europe. The danger of invasion loomed large over this country.

A conservative estimate at that time showed the number of men whom Hitler could fling into an invasion of Britain at nearly three million. Another three million Germany bayonets were poised in other directions. Remember that the Balkans had then not been overrun, that Vichy France was unoccupied and that the long Russo-German frontier was held by only about a million men.

How the picture has changed in these short but crowded years! Hitler, according to Mr. Churchill, has still about 300 divisions under arms – perhaps, four and a half million men, to which total must be added large labour forces, auxiliary services and police units, making a grand total of six million.

It would thus seem that numerically Hitler is as strong today as he was three years ago. But is he?

“The last battalion wins the war!” is a favourite slogan of the German militarists who insist that reserves are the decisive factor in modern campaigns. That is exactly where Hitler’s weakness lies. He has hardly any reserves left. As an expert military critic recently said: “The crust may still be thick; but there is little in the pie.”

By denuding his reserves Hitler has been able to retain the outward appearance of his old strength. Almost two million men of new age groups have been called to the colours in Germany during the last three years. But these men – or an equivalent number – have been lost at Stalingrad and other Russian battlefronts, in Africa and in Italy.

The Russian front even today – after many attempts to “shorten the German line” – ties down almost half of Hitler’s divisions. France, the Balkans and Italy have cut deep into the dwindling German reserves. Where three years ago German crack invasion troops threatened Great Britain a third of their number is the most Hitler can afford to ward off the Allied threat.

But there is nothing more treacherous than military mathematics, and numbers alone tell only half the story. The strength of divisions can be altered and has, indeed, radically changed during the course of the war. Numbers also allow of no reliable estimate of quality.

The figures and the distribution of the Wehrmacht, are hardly a secret.

Yet Hitler has behind him at least two major attempts at total mobilization, and his armies all over Europe now include boys of sixteen and men of nearly sixty.

A large proportion of the German veterans have been called to the colours for a second, and even a third time, and are weakened by previous wounds which, in other circumstances, would have disqualified them from further service.

That does not necessarily reflect on the fighting morale of the German troops which universally reported to be as high as ever. But the question is not whether the men want to fight so much as how good they are. And apart from the crack units of dwindling proportions they are not good.

Three years, on the other hand, have brought great progress to the mechanical equipment of the German army. The proportion of armoured and panzer divisions is today much greater than it was when German tanks triumphed in half-a-dozen European countries.

According to latest reports, the strength of anti-tank and A.A. gun formations has also vastly increased. Paratroop divisions which have proved their worth have been built up into an impressive army group.

Germany, of course, can no longer rely on much help from those satellite armies which helped her greatly in the initial stages of the Russian campaign. The Rumanian army has been decimated and is no longer a real fighting force. The Finns, even before peace parleys started, had not taken an active part in the war for a long time.

The Bulgarian divisions still perform valuable service by policing part of the Balkans and Hungarian troops still fight on the Eastern Front. In Yugoslavia, on the other hand, German divisions are tied down in a relentless war against the guerrillas.

Italy’s withdrawal from the Axis vastly affected the numerical composition of the enemy forces. But, again, military mathematics would suggest that this loss of numbers was not as great a draw-back as it would seem.

Our map sets out the figures and distribution of the German forces on the eve of invasion. Bearing all the circumstances in mind it is a formidable array of troops which confronts the Allies.

On the high seas the position has undergone even greater changes. Here, as in the air, it is not only German losses which have so radically affected the balance. It is, even more, the mighty increase in Allied strength which has tipped the scales.

Germany has now only one capital ship, the [italics] Tirpitz [/italics], left, which hardly dares to come out and fight. Except as raiders, if they ever reach the high sea from their temporary shelter in Gydnia, the two remaining battleships are of little value.

[sketch]

STILL STRONG, the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces have been grouped in anticipation of the big Allied attack on the Continent. The approximate distribution of the German divisions, the Luftwaffe squadrons and what is left of the Nazi navy is shown in this map which give a picture of the Wehrmacht on the retreat in Russia and on the defence in the West, in Italy and in the Balkans.

[italics] (continued on page 26) [/italics]

[page break]

March 25, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 17

[Photograph]

THE FARMER’S WIFE LOOKS AFTER MOTHERLESS TWINS CLUTCHING ONE SOOTY-NOSED LAMB IN HER ARMS SHE FALLS TO THE GROUND AS SHE PREVENTS ITS BROTHER FROM ESCAPING

NOW THAT SPRING IS HERE

Eric Knight, M.A., Ph.D., writes of the trials of a farmer’s life but confesses that he would not change his muddy gumboots for the finest patent leather pumps in the world

If you had motored along the Chew Valley away from Bristol on a fine pre-war summer day you would have come up against the massive shoulder of the Mendip Hills. Not gently rolling away into the dim distance, but rising steeply from a level of about 250 feet to 800 feet, at the highest point about 1,000 feet, these hills presented, even to untutored eyes, typical signs of a dairying country.

With no arable land worthy of mention there were plenty of small fields fenced off by hedges or the famous drystone walls with, everywhere, cows and plenty of young stock to follow on.

The war has changed all this. In Somerset there are six to seven times as many acres ploughed up than there were in 1939. Mendip is no exception and tractor ploughs have changed its face.

In the nation’s hour of need corn has been grown as never before, despite weather so inclement that barley has had to be harvested in November and September thunderstorms have soaked fields of corn in stook ready for hauling into the rickyard.

My farm lies on what is known as a sidling, and pretty steep some of the fields are too. One day, I tipped my plough clean over turning at the end of a furrow, which was bad for the plough as it twisted the hitch but was salutary for me as it made me circumspect when faced by special circumstances. In future I shall always keep the larger landwheel downhill when turning on a steep slope.

Machinery has been the great worry of the West Country farmer since the outbreak of war, for to plant ten acres of corn you need just as many implements as for one hundred acres. A short list of necessities would include one plough with either a tractor or two horses to pull it, a set of rollers, a set of disc harrows, a corn drill and some drags. Then, of course, for the harvest a reaperbinder is needed, so you can imagine the headaches that not only the purchase, when possible, but also the servicing of these implements have caused.

Of course, you may be able to borrow some of them. I borrow a binder from a neighbour in the valley, whose corn ripens a few days before mine. He cuts his own first, then I send my tractor down and we cut mine, and after that he probably goes right on top of the hill and cuts some more.

Lying on the slope of the Mendips, my farm enjoys the most lovely view, but I often ask myself whether that makes up for the fact that it thereby becomes what is known as a “two horse” farm. That means that whether you want to take out a load of dung to the ploughground or bring in a wagon of hay you will always have to use two horses instead of one, and to get down to brass tacks, that extra horse has to be bought and then looked after, and any costing expert will tell you that to keep a horse costs roughly fifty pounds a year. So now you can reckon what each glance at the view from the window is worth.

Such statistics are depressing things, but I feel they should be studied more carefully. After the last war people went into farming – especially poultry farming, with unbounded enthusiasm but insufficient experience and limited means.

The actual purchase or rental does not represent the main outlay, but the live and dead stock. For example, a dairy of ordinary crossbred cattle, thirty in number, might be valued at £750, while a similar sized herd of pedigree cattle such as Friesians would be worth anything from £3,000 upwards. So let the unwary back-to-the-land enthusiast beware. Expanding markets and falling prices may play havoc with his nest egg.

Obviously the aim of every farmer should be to produce the most milk from the smallest number of

OVER

[page break]

18 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

[Photograph]

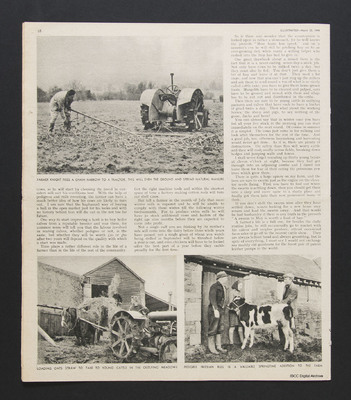

FARMER KNIGHT FIXES A CHAIN HARROW TO A TRACTOR. THIS WILL EVEN THE GROUND AND SPREAD NATURAL MANURE

cows, so he will start by choosing the breed he considers will suit his conditions best. With the help of pedigrees and milk recording, the farmer can have a much better idea of how his cows are likely to turn out. I am sure that the haphazard way of buying a bull in the open market just for his looks and with no history behind him will die out in the not too far future.

One way to start improving a herd is to buy heifer calves from a reputable breeder and rear them, for common sense will tell you that the labour involved in rearing calves, whether pedigree or not, is the same, but whether they will be worth £20 or £60 after two years will depend on the quality with which a start was made.

Time plays a rather different role in the life of a farmer than in the life of the rest of the community. Get the right machine tools and within the shortest space of time a factory making cotton reels will turn out shell cases.

But tell a farmer in the month of July that more winter milk is required and he will be unable to comply with these wishes till the following winter twelvemonth. For to produce extra milk he will have to stock additional cows and heifers of the right age nine months before they are expected to come into profit.

Not a single calf you see frisking by its mother’s side will come into the dairy before three whole years have passed; not a single grain of wheat you watch being drilled in September will be threshed before a year is out, and even chickens will have to be looked after the best part of a year before they cackle proudly for the first time.

So is there any wonder that the countryman is looked upon as rather a slowcoach, for he well knows the proverb “More haste less speed,” and on a summer’s eve he will still be pitching hay on to an ever-growing rick while many a willing helper who rushed into the fray has had to give in.

One great drawback about a mixed farm is the fact that it is a never-ending, seven-day-a-week job. Not only have cows to be milked twice a day, but they must also be fed. You don’t just give them a bit of hay and leave it at that. They need a lot more, and now that you can’t just ring up the millers and ask them to send round a ton of what is so nicely called cattle cake, you have to give them home-grown foods. Mangolds have to be cleaned and pulped, oats have to be ground and mixed with them and silage has to be cut out and distributed in the cribs.

Then there are sure to be young cattle in outlying pastures and calves that have each to have a bucket of gruel twice a day. Then what about the working horses, the sheep and pigs, to say nothing of the geese, ducks and hens?

You can almost say that in winter once you have fed all your live stock in the morning you can start immediately on the next round. Of course in summer it is simpler. The cows just come in for milking and look after themselves for the rest of the time. And a good job, too, otherwise haymaking and harvesting would never get done. As it is, there are plenty of distractions. On sultry days flies will worry cattle and they will rush madly across fields, breaking down hedges and jumping walls and fences.

I shall never forget rounding up thirty young beasts at eleven o’clock at night, because they had got through into an adjoining combe and I dared not leave them for fear of their eating the poisonous yew trees which grew there.

There is quite a large apiary on my farm, and the bees are sure to swarm just as the engine on the elevator needs fixing. First you have to find out where the swarm is settling down, then you should get them into a skep and move same to a shady place and finally get them into their new permanent home at dusk.

If you don’t shift the swarm soon after they have settled down, scouts looking for a new home may return and lead the swarm away. And that would be bad husbandry if there is any truth in the proverb “A swarm in May is worth a load of hay.”

A farmer’s life is a full one, for besides the daily routine jobs, he will occasionally go to market with his calves and surplus produce, attend occasional farm sales or go off to the nearest cattle show. They are always behind hand and always grumbling, but in spite of everything, I must say I would not exchange my muddy old gumboots for the finest pair of patent leather pumps in the world.

[Photograph]

LOADING OATS STRAW TO TAKE TO YOUNG CATTLE IN THE OUTLYING MEADOWS

[Photograph]

PEDIGREE FRIESIAN BULL IS A VALUABLE SPRINGTIME ADDITION TO THE FARM

[Photograph]

HERE ARE TWENTY LANCASTERS – TYPICAL RAID TURN OUT FOR THIS STATION – WITH SOME OF THE CREWS

TWENTY LANCASTERS

by CARL OLSSON

Do you remember the first news of a thousand bomber raid? It staggered the imagination. It still does, and so to help you appreciate what it means ILLUSTRATED, with the co-operation of Bomber Command, shows you twenty Lancasters and what it takes to send them to Berlin. Twenty multiplied by fifty is one thousand . . .

“FIFTEEN hundred ton raid on Leipzig” . . . “Two thousand tons on Berlin” . . . So the newspaper headlines run as, day after day, our air onslaught on Germany mounts in scale and intensity.

To a great many people, such figures are becoming – just figures. Symbols, scanned over briefly by the eye, a rough guide to the size and weight of the raid.

This story is an attempt to explain what lies behind those round numbers. To express, in terms of the life and work of just one R.A.F. bomber station, the nature of the toil, the cost and the prodigious human effort involved in reaching those plain tonnages of blast and flame.

[Photograph]

REPAIR AND INSPECTION. In this photograph are seen some of the men whose skill, drive and enthusiasm are responsible for getting the Lancasters back into commission in the shortest possible time after they have been damaged in attacks on important targets. Key to the numbers is as follows: 1. W.Os and N.C.Os; 2. Armourers; 3. W/T Mechanics; 4. Electricians and Instrument Makers; 5. Engine Fitters; 6. Spark Plug Testers; 7. Airframe Fitters; 8. Radio Mechanics

[Photograph]

ARMOURERS, bomb squad and load for twenty Lancasters. These are the men who are responsible for the servicing of the bombers with their offensive weapons in the shape of the giant “cookies” some of which are seen in this picture, and the incendiary containers which are used in conjunction with the high explosive bombs to add to the damage to military objectives. Officers and men have heavy responsibilities.

This is one of the war-built stations. Its aircraft strength is twenty-four Lancasters – £40,000 each as they are delivered, slick and new from the factories. Its personnel strength is about 2,500 officers and men and W.A.A.F. About one-tenth of that number are aircrews.

It costs £3,000 a week to feed the station and to clothe them all. And to clothe the ground staff and aircrews costs £40,000 – or about the cost of one Lancaster.

In the maintenance stores is a vast array of spare parts, enough to refit completely about half the aircraft on the station strength.

The stock includes such items as spare engines (£2,500 each), tail planes (£300), single Browning machine guns (£45), parachutes (£35), propellers (£350 each), turrets (£500 each), tyres (£50 each), wireless sets (£250 each), and countless other items down to rivets, screws and aluminium sheet for patching flak damage.

It is equipped to defend itself with such items as searchlights (£1,250 each), A.A. guns (£2,000 each), scout cars (£1,350 each), Bren guns (£35 each), tommy guns (£30 each), ammunition (£7 10s. for 1,000 rounds), grenades (4s. each), etc., etc.

It is a township, a factory, a battle headquarters and a front-line assault point from which men sally forth to attack the enemy. It is never at complete rest. Throughout the twenty-four hours of the day someone is working. Set down among the fields of home its 2,500 men and women can lead an entirely independent existence from the rest of the country for weeks on end.

If they are ill or injured they can get treatment in their own hospital. Canteens, kitchens and food stores big enough to supply a small town feed them. They have their own sources of recreation – playing fields, a cinema, sometimes a dance hall with a stage for variety shows.

And now let us visualise our station’s day’s work in a 2,000-ton raid scheduled for the coming night. Its share in that raid is the full station strength – twenty-four Lancasters. It is a long-distance raid to Southern Germany.

Take-off will be before dusk, say 5 p.m., so that the long journey out and home is completed before the moon rises or early morning fog settles down on the aerodrome.

By eight a.m. the handling crews will be hard at work down in the bomb dump at the far end of the aerodrome. Scores of men will be slithering about in the mud bringing hundred-pound-weight cases of incendiaries to a central section where they will be

[Photograph]

PETROL AND OIL CREWS. Motive power for our great bombers is by no means a simple matter to provide, for oil and petrol on a vast scale are required before a Lancaster sets out on a mission over enemy territory. And here you see some of the men and machines engaged on this work. They are: 1. Tractors and Drivers; 2. Oxygen trailer and Crew; 3. Salvage Crew; 4. Fire Tender Crew; 5. Oil Bowsers and their Crew; 6. Petrol Tankers and their Drivers

OVER

[page break]

14 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

TWENTY LANCASTERS – continued

packed into the special containers carried on the aircraft.

The men advance from the bomb dump in lines of ten; with the exception of the two end men, each man holds in either hand one handle of the incendiary case. Thus at each journey the men are carrying nine hundred pounds of bombs to the packing section.

In another part of the dump other men are rolling out the great 4,000-pound and 12,000-pound high explosive cookies and mounting them on to low engine-driven bomb trolleys. Others are loading flares. All this work goes on without a pause or break till the early afternoon when the trolleys are driven out to the aircraft. Lunch is a hastily eaten sandwich and a cup of tea.

Meanwhile in another section armament crews are working against time feeding tens of thousands of cartridges into the ammunition belts which will go to the gunners. Over the airfield at the tanks other men are filling the great 2,500-gallon capacity petrol bowsers and the oil bowsers, each of which holds 450 gallons.

One petrol bowser holds just enough petrol for filling one Lancaster if it is a long raiding journey. So many journeys must be made back and forth from the storage tanks to the aircraft waiting at the dispersal points. Again it is mid-afternoon before they are all filled.

At the dispersal points ground crews are swarming over the bombers in their charge. Every point in the bomber is being checked and re-checked: engines, plugs, instruments, guns, turrets, undercarriages, tyre pressures, bomb door mechanism and the host of other things. Some “snag” to one part or another of the bomber is nearly always found, and it has to be set right, with the toiling men always working against time.

If it is a fault connected with the flying ability of the aircraft it has to be set right in time for a test flight which must be made to make sure that the fault has been rectified long before take-off on the raid.

It sometimes happens that two or three test flights are made before the sweating ground crews have completed the job to the satisfaction of the captain of the aircraft.

Over at the sheds there is almost certain to be two or three bombers getting a special overhaul to put them into full serviceability at the hands of skilled maintenance crews and fitters. Perhaps whole engines may be changed, as a result of damage, patches fitted over flak holes, new instruments put in or pipe line and cables refitted.

Test flights are made in these cases, of course, and not infrequently the maintenance crews are working on the aircraft right up to a few minutes before take-off. Skilled crews have been known to refit a new engine within less than an hour before take-off. Which is certainly running it close.

While all this sweat and toil is going on in many

[Photograph]

LOADING FILM INTO MAGAZINES FOR AERIAL CAMERAS

[Photograph]

HERE ARE THE CAMERAS WHICH WILL BE USED ON THE NEXT BOMBING RAID BY THIS LANCASTER FORMATION

different parts of the airfield other special staffs are also working against time.

The intelligence officers are sweating on their filing systems getting out data about the target, getting out target maps and photographs, collecting information from Group Headquarters and from the pathfinder force engaged – all to be ready for the briefing of the crews which will take place by 2 p.m.

The meteorological officers are collecting and

[Photograph]

FLASK LOAD FOR TWENTY LANCASTERS – COUNT THEM

revising up-to-the-minute weather information from their own central channels.

In the locker rooms another staff is sorting out all the items of clothing and equipment which will be issued to each member of the air crews as soon as the briefing is over. About fifteen articles for each man ranging from life-saving waistcoats to socks.

In the kitchen Waafs are cutting sandwiches for nearly two hundred aircrew and parcelling up rations of chocolate, fruit, chewing gum and other items of refreshment.

In the station offices the Commander and other officers are selecting the crews and working out technical data for the journey. Sometimes news information comes through from group headquarters making a change of plan necessary.

It may happen that this change has to be made and most of the morning’s work altered within half an hour of the briefing.

The only people who have no part in this unceasing labour are the flying crews who will go on the raid.

Theirs, perhaps, is the worst part – the waiting from the time they are “warned” for a raid that night until the final take-off. A long wait which is broken only by the briefing and then by the dressing up in the crew room.

But everybody else on the station goes unceasingly and doggedly on until the moment comes when the last aircraft is signalled down the runway and off on its journey.

Then, and only then, do the tired ground crews, the bomb crews and the others stretch their aching limbs and take their ease in canteen or mess hall. But not for long; in an hour or so it is time for bed, to be ready for an early morning start and another long exhausting day.

[page break]

March 25, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 15

[photograph]

“HOW DID YOU DO?” AIR CHIEF MARSHAL SIR ARTHUR TRAVERS HARRIS, Air Officer Commanding in Chief, Bomber Command, gets the “gen” about the night’s big raid on Germany. His command has been called (by a neutral correspondent) the “Hammer of the Reich.” Because, for the first time since the days of Frederick the Great, the German people have been made to feel the wounds of war inside their own country. And it is the Bomber Command of the R.A.F. which has done it.

(Colour Portrait by James Jarché)

[page break]

16 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

THE WEHRMACHT AT ZERO HOUR

Where Hitler’s forces on land, on sea and in the air are awaiting attack

It was with a heavy heart that we tried to estimate the total strength of the Wehrmacht three years ago. Even a casual survey showed that the Germans had massed huge forces in the west of Europe. The danger of invasion loomed large over this country.

A conservative estimate at that time showed the number of men whom Hitler could fling into an invasion of Britain at nearly three million. Another three million Germany bayonets were poised in other directions. Remember that the Balkans had then not been overrun, that Vichy France was unoccupied and that the long Russo-German frontier was held by only about a million men.

How the picture has changed in these short but crowded years! Hitler, according to Mr. Churchill, has still about 300 divisions under arms – perhaps, four and a half million men, to which total must be added large labour forces, auxiliary services and police units, making a grand total of six million.

It would thus seem that numerically Hitler is as strong today as he was three years ago. But is he?

“The last battalion wins the war!” is a favourite slogan of the German militarists who insist that reserves are the decisive factor in modern campaigns. That is exactly where Hitler’s weakness lies. He has hardly any reserves left. As an expert military critic recently said: “The crust may still be thick; but there is little in the pie.”

By denuding his reserves Hitler has been able to retain the outward appearance of his old strength. Almost two million men of new age groups have been called to the colours in Germany during the last three years. But these men – or an equivalent number – have been lost at Stalingrad and other Russian battlefronts, in Africa and in Italy.

The Russian front even today – after many attempts to “shorten the German line” – ties down almost half of Hitler’s divisions. France, the Balkans and Italy have cut deep into the dwindling German reserves. Where three years ago German crack invasion troops threatened Great Britain a third of their number is the most Hitler can afford to ward off the Allied threat.

But there is nothing more treacherous than military mathematics, and numbers alone tell only half the story. The strength of divisions can be altered and has, indeed, radically changed during the course of the war. Numbers also allow of no reliable estimate of quality.

The figures and the distribution of the Wehrmacht, are hardly a secret.

Yet Hitler has behind him at least two major attempts at total mobilization, and his armies all over Europe now include boys of sixteen and men of nearly sixty.

A large proportion of the German veterans have been called to the colours for a second, and even a third time, and are weakened by previous wounds which, in other circumstances, would have disqualified them from further service.

That does not necessarily reflect on the fighting morale of the German troops which universally reported to be as high as ever. But the question is not whether the men want to fight so much as how good they are. And apart from the crack units of dwindling proportions they are not good.

Three years, on the other hand, have brought great progress to the mechanical equipment of the German army. The proportion of armoured and panzer divisions is today much greater than it was when German tanks triumphed in half-a-dozen European countries.

According to latest reports, the strength of anti-tank and A.A. gun formations has also vastly increased. Paratroop divisions which have proved their worth have been built up into an impressive army group.

Germany, of course, can no longer rely on much help from those satellite armies which helped her greatly in the initial stages of the Russian campaign. The Rumanian army has been decimated and is no longer a real fighting force. The Finns, even before peace parleys started, had not taken an active part in the war for a long time.

The Bulgarian divisions still perform valuable service by policing part of the Balkans and Hungarian troops still fight on the Eastern Front. In Yugoslavia, on the other hand, German divisions are tied down in a relentless war against the guerrillas.

Italy’s withdrawal from the Axis vastly affected the numerical composition of the enemy forces. But, again, military mathematics would suggest that this loss of numbers was not as great a draw-back as it would seem.

Our map sets out the figures and distribution of the German forces on the eve of invasion. Bearing all the circumstances in mind it is a formidable array of troops which confronts the Allies.

On the high seas the position has undergone even greater changes. Here, as in the air, it is not only German losses which have so radically affected the balance. It is, even more, the mighty increase in Allied strength which has tipped the scales.

Germany has now only one capital ship, the [italics] Tirpitz [/italics], left, which hardly dares to come out and fight. Except as raiders, if they ever reach the high sea from their temporary shelter in Gydnia, the two remaining battleships are of little value.

[sketch]

STILL STRONG, the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces have been grouped in anticipation of the big Allied attack on the Continent. The approximate distribution of the German divisions, the Luftwaffe squadrons and what is left of the Nazi navy is shown in this map which give a picture of the Wehrmacht on the retreat in Russia and on the defence in the West, in Italy and in the Balkans.

[italics] (continued on page 26) [/italics]

[page break]

March 25, 1944 – ILLUSTRATED 17

[Photograph]

THE FARMER’S WIFE LOOKS AFTER MOTHERLESS TWINS CLUTCHING ONE SOOTY-NOSED LAMB IN HER ARMS SHE FALLS TO THE GROUND AS SHE PREVENTS ITS BROTHER FROM ESCAPING

NOW THAT SPRING IS HERE

Eric Knight, M.A., Ph.D., writes of the trials of a farmer’s life but confesses that he would not change his muddy gumboots for the finest patent leather pumps in the world

If you had motored along the Chew Valley away from Bristol on a fine pre-war summer day you would have come up against the massive shoulder of the Mendip Hills. Not gently rolling away into the dim distance, but rising steeply from a level of about 250 feet to 800 feet, at the highest point about 1,000 feet, these hills presented, even to untutored eyes, typical signs of a dairying country.

With no arable land worthy of mention there were plenty of small fields fenced off by hedges or the famous drystone walls with, everywhere, cows and plenty of young stock to follow on.

The war has changed all this. In Somerset there are six to seven times as many acres ploughed up than there were in 1939. Mendip is no exception and tractor ploughs have changed its face.

In the nation’s hour of need corn has been grown as never before, despite weather so inclement that barley has had to be harvested in November and September thunderstorms have soaked fields of corn in stook ready for hauling into the rickyard.

My farm lies on what is known as a sidling, and pretty steep some of the fields are too. One day, I tipped my plough clean over turning at the end of a furrow, which was bad for the plough as it twisted the hitch but was salutary for me as it made me circumspect when faced by special circumstances. In future I shall always keep the larger landwheel downhill when turning on a steep slope.

Machinery has been the great worry of the West Country farmer since the outbreak of war, for to plant ten acres of corn you need just as many implements as for one hundred acres. A short list of necessities would include one plough with either a tractor or two horses to pull it, a set of rollers, a set of disc harrows, a corn drill and some drags. Then, of course, for the harvest a reaperbinder is needed, so you can imagine the headaches that not only the purchase, when possible, but also the servicing of these implements have caused.

Of course, you may be able to borrow some of them. I borrow a binder from a neighbour in the valley, whose corn ripens a few days before mine. He cuts his own first, then I send my tractor down and we cut mine, and after that he probably goes right on top of the hill and cuts some more.

Lying on the slope of the Mendips, my farm enjoys the most lovely view, but I often ask myself whether that makes up for the fact that it thereby becomes what is known as a “two horse” farm. That means that whether you want to take out a load of dung to the ploughground or bring in a wagon of hay you will always have to use two horses instead of one, and to get down to brass tacks, that extra horse has to be bought and then looked after, and any costing expert will tell you that to keep a horse costs roughly fifty pounds a year. So now you can reckon what each glance at the view from the window is worth.

Such statistics are depressing things, but I feel they should be studied more carefully. After the last war people went into farming – especially poultry farming, with unbounded enthusiasm but insufficient experience and limited means.

The actual purchase or rental does not represent the main outlay, but the live and dead stock. For example, a dairy of ordinary crossbred cattle, thirty in number, might be valued at £750, while a similar sized herd of pedigree cattle such as Friesians would be worth anything from £3,000 upwards. So let the unwary back-to-the-land enthusiast beware. Expanding markets and falling prices may play havoc with his nest egg.

Obviously the aim of every farmer should be to produce the most milk from the smallest number of

OVER

[page break]

18 ILLUSTRATED – March 25, 1944

[Photograph]

FARMER KNIGHT FIXES A CHAIN HARROW TO A TRACTOR. THIS WILL EVEN THE GROUND AND SPREAD NATURAL MANURE

cows, so he will start by choosing the breed he considers will suit his conditions best. With the help of pedigrees and milk recording, the farmer can have a much better idea of how his cows are likely to turn out. I am sure that the haphazard way of buying a bull in the open market just for his looks and with no history behind him will die out in the not too far future.

One way to start improving a herd is to buy heifer calves from a reputable breeder and rear them, for common sense will tell you that the labour involved in rearing calves, whether pedigree or not, is the same, but whether they will be worth £20 or £60 after two years will depend on the quality with which a start was made.

Time plays a rather different role in the life of a farmer than in the life of the rest of the community. Get the right machine tools and within the shortest space of time a factory making cotton reels will turn out shell cases.

But tell a farmer in the month of July that more winter milk is required and he will be unable to comply with these wishes till the following winter twelvemonth. For to produce extra milk he will have to stock additional cows and heifers of the right age nine months before they are expected to come into profit.

Not a single calf you see frisking by its mother’s side will come into the dairy before three whole years have passed; not a single grain of wheat you watch being drilled in September will be threshed before a year is out, and even chickens will have to be looked after the best part of a year before they cackle proudly for the first time.

So is there any wonder that the countryman is looked upon as rather a slowcoach, for he well knows the proverb “More haste less speed,” and on a summer’s eve he will still be pitching hay on to an ever-growing rick while many a willing helper who rushed into the fray has had to give in.

One great drawback about a mixed farm is the fact that it is a never-ending, seven-day-a-week job. Not only have cows to be milked twice a day, but they must also be fed. You don’t just give them a bit of hay and leave it at that. They need a lot more, and now that you can’t just ring up the millers and ask them to send round a ton of what is so nicely called cattle cake, you have to give them home-grown foods. Mangolds have to be cleaned and pulped, oats have to be ground and mixed with them and silage has to be cut out and distributed in the cribs.

Then there are sure to be young cattle in outlying pastures and calves that have each to have a bucket of gruel twice a day. Then what about the working horses, the sheep and pigs, to say nothing of the geese, ducks and hens?

You can almost say that in winter once you have fed all your live stock in the morning you can start immediately on the next round. Of course in summer it is simpler. The cows just come in for milking and look after themselves for the rest of the time. And a good job, too, otherwise haymaking and harvesting would never get done. As it is, there are plenty of distractions. On sultry days flies will worry cattle and they will rush madly across fields, breaking down hedges and jumping walls and fences.

I shall never forget rounding up thirty young beasts at eleven o’clock at night, because they had got through into an adjoining combe and I dared not leave them for fear of their eating the poisonous yew trees which grew there.

There is quite a large apiary on my farm, and the bees are sure to swarm just as the engine on the elevator needs fixing. First you have to find out where the swarm is settling down, then you should get them into a skep and move same to a shady place and finally get them into their new permanent home at dusk.

If you don’t shift the swarm soon after they have settled down, scouts looking for a new home may return and lead the swarm away. And that would be bad husbandry if there is any truth in the proverb “A swarm in May is worth a load of hay.”

A farmer’s life is a full one, for besides the daily routine jobs, he will occasionally go to market with his calves and surplus produce, attend occasional farm sales or go off to the nearest cattle show. They are always behind hand and always grumbling, but in spite of everything, I must say I would not exchange my muddy old gumboots for the finest pair of patent leather pumps in the world.

[Photograph]

LOADING OATS STRAW TO TAKE TO YOUNG CATTLE IN THE OUTLYING MEADOWS

[Photograph]

PEDIGREE FRIESIAN BULL IS A VALUABLE SPRINGTIME ADDITION TO THE FARM

Collection

Citation

“Twenty Lancasters,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed November 13, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/17626.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.