Recollections - Warrant Officer B F Hughes

Title

Recollections - Warrant Officer B F Hughes

Description

Account of operation to Nuremberg on 28 August 1942 in Halifax where aircraft was attacked and shot down by night fighter. Continues with account of capture, interrogation and transport to prisoner of war camp. Describes camp occupants, situation, facilities, barracks, compounds, roll call. Continues with conditions/retaliations after Dieppe raid. Concludes with short account of long march as Russians approach.

Creator

Date

2014-06-26

Temporal Coverage

Spatial Coverage

Language

Format

Six page printed document

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

MDryhurstHG1332214-160608-05

Transcription

Recollections – Warrant Officer BF Hughes (Service No NZ402870

RNZAF)

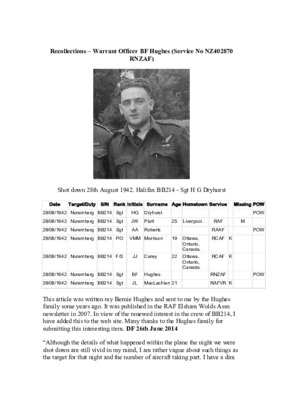

[black and white photograph – Bernie Hughes]

Shot down 28th August 1942. Halifax BB214 - Sgt H G Dryhurst

Date Target/Duty S/N Rank Initials Surname Age Hometown Service Missing POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt HG Dryhurst POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt JW Platt 25 Liverpool. RAF M

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt AA Roberts RAAF POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 P/O VMM Morrison 19 Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. RCAF K

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 F/S JJ Carey 22 Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. RCAF K

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt BF Hughes RNZAF POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt JL MacLachlan 21 RAFVR K

This article was written by Bernie Hughes and sent to me by the Hughes

family some years ago. It was published in the RAF Elsham Wolds Assn

newsletter in 2007. In view of the renewed interest in the crew of BB214, I

have added this to the web site. Many thanks to the Hughes family for

submitting this interesting item. DF 26th June 2014

“Although the details of what happened within the plane the night we were

shot down are still vivid in my mind, I am rather vague about such things as

the target for that night and the number of aircraft taking part. I have a dim

[page break]

recollection that the target was Nuremburg, that the number of aircraft was

about 800 and that for the first time we were dropping bombs not pamphlets

on that city. I could be mixed up with the stories shared by us later in our

P.O.W. camp in Ober-Silesia of course, but it is my recollection that

Nuremburg was our target.

We had an uneventful flight across the Channel until we reached the French

coast where all hell broke loose. Very heavy anti-aircraft fire was

encountered and we had n extremely busy time trying to avoid being hit.

Eventually we had escaped it and pressed on towards our target. Along the

route we saw heavy outbursts of gunfire on both sides of us, but apart from

two or three awkward patches we seemed to be having a charmed run. I was

just congratulating myself that we were going to have a rather easy trip

when without warning there was a shattering sound of bullets cutting

through metal, an explosion, flames everywhere and much coloured smoke.

I was normally the tail-gunner in the crew but on changing over from

Wellington bombers to Halifax bombers, I asked to change over to midupper

turret for a few flights to see what a difference it made. Underneath

my feet in the fuselage, flares were exploding, there was a lot of smoke and

flames, and I could not see out of my turret. The plane was now in a dive

and I slid out of the turret to get my parachute and clip it on to my harness. I

have always been afraid of heights often “freezing” when climbing a ladder

to get on to a wall or roof, and I had sworn that I would always stay with my

plane as I felt I would be too terrified to bale out. However, when your life

is out on a limb you forget your fears quickly and your main aim is to do

anything to preserve yourself. I attempted firstly to get through to the front

of the plane to contact the skipper. Finding this impossible I then tried to

open the door into the rear-gunner’s turret but this seemed jammed and

would not budge. By this time I was praying, cursing, laughing and crying. I

tried to open the entrance hatch to make my escape, but it would not move. I

kicked, screamed and yelled and after what seemed an eternity I finally got

the hatch open. I turned onto my stomach to slide out into space and my

harness caught on a jagged piece of metal as I went through the hatch. I

found myself pressed against the fuselage like a fly on a wall while the

plane plunged towards earth. I consider only God got me off that hook.

When, after what I consider the worst few minutes in my life up till then, I

finally broke free from the plane. I found everything so peaceful that I

delayed pulling the handle of the ripcord. When I did it was to find a forest

of trees coming up to meet me. I landed in a wheat field completely

surrounded by trees. I could hear machine gun fire in the skies above me and

the barking of dogs through the trees. I rolled up my parachute, and together

with escape documents that I tried to tear up, hid them under a wheat stack

and proceeded through the trees on to a road, which sloped downwards. I

started to walk down this road when I was suddenly confronted by a youth

who peacefully but urgently tried to stop me and pointed in the

[page break]

opposite direction. He kept saying, what I figured out later when I had learnt some

basic German words, “Deutschen Zoldaten”. Later on when I had time to

think more clearly I figured out that he must have been the son of a foreign

worker forced to work in Germany, and that he was trying to warn me to

make off in the opposite direction. Later when I saw him in the crowd that

gathered as my captors brought me to headquarters I smiled at him but he

ignored me. I must have been in a state of shock after my escape from the

plane and parachute descent because I did so many stupid things and took no

evasive action.

I continued down the road, around a bend, and without warning two German

Air Force soldiers stepped from behind the trees and with rifles pointed at

my back, they shouted at me to halt. They marched me down to what

seemed to be part of a monastery building that presumably had been

commandeered for war purposes. I was told there was a night-fighter base

nearby and that the pilot who had shot us down was from that base.

My interrogation was conducted firmly but courteously. I gave my name,

number and rank but refused to provide further information. I was advised

by my interrogators that they knew my squadron, but merely wanted my to

verify the information. I said if they knew so much there was no need for me

to add anything further. I must add that their information was pretty accurate

but I refused to tell them so. Being still a little shocked might have helped

me. I was told that Harry Dryhurst, the Skipper, had his parachute caught in

the trees and had to unbuckle himself and drop into a canvas sheet held by

his captors. Also that Roberts, the Navigator, was captured and was being

interrogated, that the plane had dived into a lake and was on the bottom, and

that the bodies of the crew had been recovered. From the information they

gave me later I thought that only one body remained in the plane, John

Carey, the Canadian front-gunner.

After the interrogation we were taken by train the next day to a P.O.W. entry

camp. Here we were put in solitary cells. I spent about five or six days in

solitary. I think the idea was to break you down a little so they could obtain

further information from you.

I recall in the cell next to mine the window was open and I could hear the

inmate giving lots of information about life on his squadron and how

bomber crews reacted to raids, and how big the turnover was in aircrew. I

still think this was a plant because I was interrogated not long after that and

told I should co-operate more like many of my comrades. In case it was not

a plant I mention the matter to the senior British officer when we were

released into the main camp after solitary confinement. Solitary

confinement, though not harsh or cruel, was very unnerving to young men

coming straight from the free and easy camaraderie of an RAF squadron.

[page break]

Release into the main camp was like an unexpected holiday. Here one could

talk, read, play games, enjoy comradeship and have more satisfactory meals

(Red Cross parcels, not German black bread, watery vegetable soup and

ersatz coffee). Perhaps the greatest release was the feeling of space and not

the claustrophobia of being shut up within four narrow walls.

After a short stay at this quite pleasant camp we were entrained and taken by

rail to the huge P.O.W camp Stalag V111B – Lamsdorf, in Ober-Silesia on

the border of Poland. This camp contained P.O.W.s from practically every

war front commencing from the British Expeditionary Force in France up

till Dunkirk, Greece and Crete, the Desert, the Mediterranean, Sicily and

Italy. There were British, Anzacs, Canadians many captured after the

abortive Dieppe raid, South Africans, Ghurkas, Americans and

representatives from all the nations involved on the British side in the war.

Although it was mainly an Army camp there were naval men and members

of specialist groups such Parachutists, Commandos, Desert Long Range

Groups and approximately one thousand Air Force men. From memory

there were about ten thousand men in the camp at any one time, plus a total

of nearly ten thousand men in various working parties attached to the camp

for administrative purposes.

The camp was divided into compounds with approximately one thousand

men in each, living in stone barracks with concrete floors and wooden

shutters covering the window openings. In the middle of each barrack was a

washroom containing cold water, washbasins and a stone copper for boiling

water when wood was available. About a hundred men lived in each half of

a barrack with three-tiered bunks in rows on one side of the room and

wooden trestles with wooden frames on the other side. There was an outside

latrine (a forty-holer we called it) built from the same materials as the

barracks and with a covered sump at the back. Periodically, a horse-drawn

wooden tank was brought into the compound, the wooden covers of the

sump were opened and the human waste pumped into the tank. The tanks

was then driven from the camp into the surrounding fields and used as

manure. In the summer the latrine smelt to the high heavens. In the winter it

was a severe penance to go to the latrine as it was icy cold, there being no

doors nor shutters over the windows. As it was not permitted to go outside

the barracks at night a wooden tub was positioned inside the porch for toilet

purposes. Barrack inmates were rostered each night to carry out the tub and

dispose of the waste. It was not a pleasant duty but luckily only happened

two or three times a year for each man.

Life in each compound varied according to circumstances. At normal times

the gates of each compound were opened at 9.00am and locked at 4.00pm in

the winter or 6.00pm in the summer. Inmates of one compound could visit

inmates of another or go to lectures in the school building, or play sport on

[page break]

the two clay sites set aside for this purpose, or go under guard to the shower

block on their rostered day of the week. Some nights there were stage

performances in the theatre building and different compounds, whose turn it

was that night, were escorted under guard from their compounds to the

theatre and back afterwards. Roll call was taken in the morning and

afternoon to coincide with the opening and closing of the compound gates.

Normally this took 10 – 15 minutes but every so often if there had been an

escape from the camp or radio sets, which were strictly forbidden, had been

found in the barracks then the compound inmates could be kept out on

parade for hours. On one particular occasion we were kept on parade from

9.00am until after mid-afternoon with only the proven sick allowed to sit on

the ground for short periods of about 10 minutes. There was a strong protest

by the senior British representative but this was ignored by the German

control, as were other protests. There were frequent interruptions to the

normal running of the camp when compounds were kept locked. Classes,

lectures and the theatre were shut down and apart from visits to the latrine

under guard no movement was permitted between barracks in the same

compound. This was also a grim time as Red Cross parcels were not allowed

to be distributed and the inmates had to exist on German rations such as

watery vegetable soup, or fish soup with fish heads swimming in it, black

bread, ersatz jam, or fish cheese (a vile tasting and smelling concoction) and

black ersatz coffee.

Perhaps one of the worst periods for the camp was just after the Dieppe raid

by the Canadians. Some of the German prisoners captured by the Canadians

after their initial landing were found dead on the beach with their hands

bound behind their backs. The Germans at first thought they had been bound

and then shot by the Canadians and it was not until later they realised they

had been killed by flying bullets, probably from their own side, when the

Canadian attack was repulsed and the few who escaped were driven from

the beach.

However, in retaliation, for what the German Command at first thought was

a British atrocity all Air Force personnel in the RAF compound at Lamsdorf,

as well as all Army personnel, in the other compounds of the rank of

Corporal or over had their hands tightly bound with very strong string from

early in the morning till evening. They were not permitted out of their

barracks except under guard to the latrine. German front rank troops from

the Russian front, who were on home leave, were brought in as extra guards.

Armed with quick-firing rifles with bayonets attached they patrolled four to

each end barracks. They were fine soldiers, unable to be bribed like normal

guards, who once bribed, could be forced to bring into the compound

forbidden items such as parts of a radio, tools, clothing etc.

[page break]

These soldiers were not at all happy about doing guard duty in a P.O.W.

camp but they did it with quiet efficiency, firmness and no cruelty. This

period lasted for four to six weeks. With the demand from various war

fronts for more experienced troops these guards were pulled out and

replaced with the normal camp guards posted outside each compound. The

string around our wrists was replaced by handcuffs. These were brought in a

large tray into each end barrack by two guards. Each P.O.W. had to put on

his own handcuffs and keep them on until they were unlocked at the end of

the day. Gradually, the mean learned to open the handcuffs with a nail or

similar shaped object and the whole operation became a farce. In the end the

guards were bringing in the trays, leaving them in the porch and collecting

them in the evening. This particular period of reprisal occupied several

months before dying out. The next major disruption in the camp took place

at the end of December 1944.

The Russians were breaking through on the Eastern front and the Germans

decided to move the occupants of StalagV111B westwards. Each occupant

was issued with a Red Cross parcel of food and told to carry whatever

clothes and personal item he could manage. Under armed guard we started

to march westwards through the cold and snow of a severe eastern European

winter. We were billeted overnight wherever room could be found for each

group in large buildings, other unoccupied camps, churches and factories.

Many of us contracted Dysentery, various types of stomach ailment, feet

troubles and because of lack of bathing, lice.

Eventually with another RAF friend and a British Army friend of his, we

escaped from the main march, and after a series of adventures we contacted

a party of Polish foreign workers on a party complex. With their help and

guidance we hid up in a barn where they kept a farm tractor. For over a

week they smuggled food and drink to us when they came each morning to

collect the tractor. The last day they advised us that American troops were

approaching the area and they would have to lie low to avoid being caught

in any military action. That night there was a fierce battle. In the morning

we could hear tanks rumbling along the road, then the sound of motor driven

vehicles approaching the barn. We buried ourselves deeper in to the hay.

The doors were flung open and an American voice called out, “Okay fellows

you can come out now. The Americans are here.”

It was April 9th, the greatest day in our prisoner of war life. The outfit that

rescued us was the Second Battalion Combat team 23, Second Division

(Infantry), 1st Army, Officer Commanding Lieut/Colonel William A Smith.

I have his autograph and I have kept it since the war years.” Bernie Hughes

This item is courtesy of the Hughes family in New Zealand.

RNZAF)

[black and white photograph – Bernie Hughes]

Shot down 28th August 1942. Halifax BB214 - Sgt H G Dryhurst

Date Target/Duty S/N Rank Initials Surname Age Hometown Service Missing POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt HG Dryhurst POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt JW Platt 25 Liverpool. RAF M

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt AA Roberts RAAF POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 P/O VMM Morrison 19 Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. RCAF K

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 F/S JJ Carey 22 Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. RCAF K

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt BF Hughes RNZAF POW

28/08/1942 Nuremberg BB214 Sgt JL MacLachlan 21 RAFVR K

This article was written by Bernie Hughes and sent to me by the Hughes

family some years ago. It was published in the RAF Elsham Wolds Assn

newsletter in 2007. In view of the renewed interest in the crew of BB214, I

have added this to the web site. Many thanks to the Hughes family for

submitting this interesting item. DF 26th June 2014

“Although the details of what happened within the plane the night we were

shot down are still vivid in my mind, I am rather vague about such things as

the target for that night and the number of aircraft taking part. I have a dim

[page break]

recollection that the target was Nuremburg, that the number of aircraft was

about 800 and that for the first time we were dropping bombs not pamphlets

on that city. I could be mixed up with the stories shared by us later in our

P.O.W. camp in Ober-Silesia of course, but it is my recollection that

Nuremburg was our target.

We had an uneventful flight across the Channel until we reached the French

coast where all hell broke loose. Very heavy anti-aircraft fire was

encountered and we had n extremely busy time trying to avoid being hit.

Eventually we had escaped it and pressed on towards our target. Along the

route we saw heavy outbursts of gunfire on both sides of us, but apart from

two or three awkward patches we seemed to be having a charmed run. I was

just congratulating myself that we were going to have a rather easy trip

when without warning there was a shattering sound of bullets cutting

through metal, an explosion, flames everywhere and much coloured smoke.

I was normally the tail-gunner in the crew but on changing over from

Wellington bombers to Halifax bombers, I asked to change over to midupper

turret for a few flights to see what a difference it made. Underneath

my feet in the fuselage, flares were exploding, there was a lot of smoke and

flames, and I could not see out of my turret. The plane was now in a dive

and I slid out of the turret to get my parachute and clip it on to my harness. I

have always been afraid of heights often “freezing” when climbing a ladder

to get on to a wall or roof, and I had sworn that I would always stay with my

plane as I felt I would be too terrified to bale out. However, when your life

is out on a limb you forget your fears quickly and your main aim is to do

anything to preserve yourself. I attempted firstly to get through to the front

of the plane to contact the skipper. Finding this impossible I then tried to

open the door into the rear-gunner’s turret but this seemed jammed and

would not budge. By this time I was praying, cursing, laughing and crying. I

tried to open the entrance hatch to make my escape, but it would not move. I

kicked, screamed and yelled and after what seemed an eternity I finally got

the hatch open. I turned onto my stomach to slide out into space and my

harness caught on a jagged piece of metal as I went through the hatch. I

found myself pressed against the fuselage like a fly on a wall while the

plane plunged towards earth. I consider only God got me off that hook.

When, after what I consider the worst few minutes in my life up till then, I

finally broke free from the plane. I found everything so peaceful that I

delayed pulling the handle of the ripcord. When I did it was to find a forest

of trees coming up to meet me. I landed in a wheat field completely

surrounded by trees. I could hear machine gun fire in the skies above me and

the barking of dogs through the trees. I rolled up my parachute, and together

with escape documents that I tried to tear up, hid them under a wheat stack

and proceeded through the trees on to a road, which sloped downwards. I

started to walk down this road when I was suddenly confronted by a youth

who peacefully but urgently tried to stop me and pointed in the

[page break]

opposite direction. He kept saying, what I figured out later when I had learnt some

basic German words, “Deutschen Zoldaten”. Later on when I had time to

think more clearly I figured out that he must have been the son of a foreign

worker forced to work in Germany, and that he was trying to warn me to

make off in the opposite direction. Later when I saw him in the crowd that

gathered as my captors brought me to headquarters I smiled at him but he

ignored me. I must have been in a state of shock after my escape from the

plane and parachute descent because I did so many stupid things and took no

evasive action.

I continued down the road, around a bend, and without warning two German

Air Force soldiers stepped from behind the trees and with rifles pointed at

my back, they shouted at me to halt. They marched me down to what

seemed to be part of a monastery building that presumably had been

commandeered for war purposes. I was told there was a night-fighter base

nearby and that the pilot who had shot us down was from that base.

My interrogation was conducted firmly but courteously. I gave my name,

number and rank but refused to provide further information. I was advised

by my interrogators that they knew my squadron, but merely wanted my to

verify the information. I said if they knew so much there was no need for me

to add anything further. I must add that their information was pretty accurate

but I refused to tell them so. Being still a little shocked might have helped

me. I was told that Harry Dryhurst, the Skipper, had his parachute caught in

the trees and had to unbuckle himself and drop into a canvas sheet held by

his captors. Also that Roberts, the Navigator, was captured and was being

interrogated, that the plane had dived into a lake and was on the bottom, and

that the bodies of the crew had been recovered. From the information they

gave me later I thought that only one body remained in the plane, John

Carey, the Canadian front-gunner.

After the interrogation we were taken by train the next day to a P.O.W. entry

camp. Here we were put in solitary cells. I spent about five or six days in

solitary. I think the idea was to break you down a little so they could obtain

further information from you.

I recall in the cell next to mine the window was open and I could hear the

inmate giving lots of information about life on his squadron and how

bomber crews reacted to raids, and how big the turnover was in aircrew. I

still think this was a plant because I was interrogated not long after that and

told I should co-operate more like many of my comrades. In case it was not

a plant I mention the matter to the senior British officer when we were

released into the main camp after solitary confinement. Solitary

confinement, though not harsh or cruel, was very unnerving to young men

coming straight from the free and easy camaraderie of an RAF squadron.

[page break]

Release into the main camp was like an unexpected holiday. Here one could

talk, read, play games, enjoy comradeship and have more satisfactory meals

(Red Cross parcels, not German black bread, watery vegetable soup and

ersatz coffee). Perhaps the greatest release was the feeling of space and not

the claustrophobia of being shut up within four narrow walls.

After a short stay at this quite pleasant camp we were entrained and taken by

rail to the huge P.O.W camp Stalag V111B – Lamsdorf, in Ober-Silesia on

the border of Poland. This camp contained P.O.W.s from practically every

war front commencing from the British Expeditionary Force in France up

till Dunkirk, Greece and Crete, the Desert, the Mediterranean, Sicily and

Italy. There were British, Anzacs, Canadians many captured after the

abortive Dieppe raid, South Africans, Ghurkas, Americans and

representatives from all the nations involved on the British side in the war.

Although it was mainly an Army camp there were naval men and members

of specialist groups such Parachutists, Commandos, Desert Long Range

Groups and approximately one thousand Air Force men. From memory

there were about ten thousand men in the camp at any one time, plus a total

of nearly ten thousand men in various working parties attached to the camp

for administrative purposes.

The camp was divided into compounds with approximately one thousand

men in each, living in stone barracks with concrete floors and wooden

shutters covering the window openings. In the middle of each barrack was a

washroom containing cold water, washbasins and a stone copper for boiling

water when wood was available. About a hundred men lived in each half of

a barrack with three-tiered bunks in rows on one side of the room and

wooden trestles with wooden frames on the other side. There was an outside

latrine (a forty-holer we called it) built from the same materials as the

barracks and with a covered sump at the back. Periodically, a horse-drawn

wooden tank was brought into the compound, the wooden covers of the

sump were opened and the human waste pumped into the tank. The tanks

was then driven from the camp into the surrounding fields and used as

manure. In the summer the latrine smelt to the high heavens. In the winter it

was a severe penance to go to the latrine as it was icy cold, there being no

doors nor shutters over the windows. As it was not permitted to go outside

the barracks at night a wooden tub was positioned inside the porch for toilet

purposes. Barrack inmates were rostered each night to carry out the tub and

dispose of the waste. It was not a pleasant duty but luckily only happened

two or three times a year for each man.

Life in each compound varied according to circumstances. At normal times

the gates of each compound were opened at 9.00am and locked at 4.00pm in

the winter or 6.00pm in the summer. Inmates of one compound could visit

inmates of another or go to lectures in the school building, or play sport on

[page break]

the two clay sites set aside for this purpose, or go under guard to the shower

block on their rostered day of the week. Some nights there were stage

performances in the theatre building and different compounds, whose turn it

was that night, were escorted under guard from their compounds to the

theatre and back afterwards. Roll call was taken in the morning and

afternoon to coincide with the opening and closing of the compound gates.

Normally this took 10 – 15 minutes but every so often if there had been an

escape from the camp or radio sets, which were strictly forbidden, had been

found in the barracks then the compound inmates could be kept out on

parade for hours. On one particular occasion we were kept on parade from

9.00am until after mid-afternoon with only the proven sick allowed to sit on

the ground for short periods of about 10 minutes. There was a strong protest

by the senior British representative but this was ignored by the German

control, as were other protests. There were frequent interruptions to the

normal running of the camp when compounds were kept locked. Classes,

lectures and the theatre were shut down and apart from visits to the latrine

under guard no movement was permitted between barracks in the same

compound. This was also a grim time as Red Cross parcels were not allowed

to be distributed and the inmates had to exist on German rations such as

watery vegetable soup, or fish soup with fish heads swimming in it, black

bread, ersatz jam, or fish cheese (a vile tasting and smelling concoction) and

black ersatz coffee.

Perhaps one of the worst periods for the camp was just after the Dieppe raid

by the Canadians. Some of the German prisoners captured by the Canadians

after their initial landing were found dead on the beach with their hands

bound behind their backs. The Germans at first thought they had been bound

and then shot by the Canadians and it was not until later they realised they

had been killed by flying bullets, probably from their own side, when the

Canadian attack was repulsed and the few who escaped were driven from

the beach.

However, in retaliation, for what the German Command at first thought was

a British atrocity all Air Force personnel in the RAF compound at Lamsdorf,

as well as all Army personnel, in the other compounds of the rank of

Corporal or over had their hands tightly bound with very strong string from

early in the morning till evening. They were not permitted out of their

barracks except under guard to the latrine. German front rank troops from

the Russian front, who were on home leave, were brought in as extra guards.

Armed with quick-firing rifles with bayonets attached they patrolled four to

each end barracks. They were fine soldiers, unable to be bribed like normal

guards, who once bribed, could be forced to bring into the compound

forbidden items such as parts of a radio, tools, clothing etc.

[page break]

These soldiers were not at all happy about doing guard duty in a P.O.W.

camp but they did it with quiet efficiency, firmness and no cruelty. This

period lasted for four to six weeks. With the demand from various war

fronts for more experienced troops these guards were pulled out and

replaced with the normal camp guards posted outside each compound. The

string around our wrists was replaced by handcuffs. These were brought in a

large tray into each end barrack by two guards. Each P.O.W. had to put on

his own handcuffs and keep them on until they were unlocked at the end of

the day. Gradually, the mean learned to open the handcuffs with a nail or

similar shaped object and the whole operation became a farce. In the end the

guards were bringing in the trays, leaving them in the porch and collecting

them in the evening. This particular period of reprisal occupied several

months before dying out. The next major disruption in the camp took place

at the end of December 1944.

The Russians were breaking through on the Eastern front and the Germans

decided to move the occupants of StalagV111B westwards. Each occupant

was issued with a Red Cross parcel of food and told to carry whatever

clothes and personal item he could manage. Under armed guard we started

to march westwards through the cold and snow of a severe eastern European

winter. We were billeted overnight wherever room could be found for each

group in large buildings, other unoccupied camps, churches and factories.

Many of us contracted Dysentery, various types of stomach ailment, feet

troubles and because of lack of bathing, lice.

Eventually with another RAF friend and a British Army friend of his, we

escaped from the main march, and after a series of adventures we contacted

a party of Polish foreign workers on a party complex. With their help and

guidance we hid up in a barn where they kept a farm tractor. For over a

week they smuggled food and drink to us when they came each morning to

collect the tractor. The last day they advised us that American troops were

approaching the area and they would have to lie low to avoid being caught

in any military action. That night there was a fierce battle. In the morning

we could hear tanks rumbling along the road, then the sound of motor driven

vehicles approaching the barn. We buried ourselves deeper in to the hay.

The doors were flung open and an American voice called out, “Okay fellows

you can come out now. The Americans are here.”

It was April 9th, the greatest day in our prisoner of war life. The outfit that

rescued us was the Second Battalion Combat team 23, Second Division

(Infantry), 1st Army, Officer Commanding Lieut/Colonel William A Smith.

I have his autograph and I have kept it since the war years.” Bernie Hughes

This item is courtesy of the Hughes family in New Zealand.

Collection

Citation

B F Hughes, “Recollections - Warrant Officer B F Hughes,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed October 29, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/28684.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.