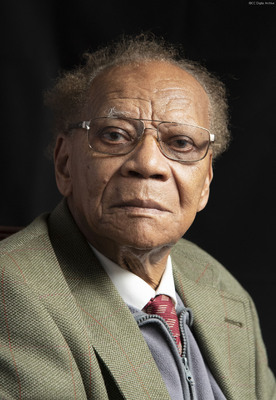

Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. Two

Title

Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. Two

Description

Ralph Ottey joined the RAF from Jamaica. After the war he returned to Jamaica. However, he had met the woman he was to later marry while based in the UK and returned to the settle here. He settled in Boston and had a long career with a local firm. On his retirement he worked for the Chamber of Commerce and wrote several books about Boston.

Creator

Date

2020-08-28

Language

Type

Format

00:59:28 Audio Recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AOtteyRA200828-01, POtteyRA2001, POtteyRA2002

Transcription

HH: Okay. So, today is Friday the 28th of August 2020 and I’m Heather Hughes and we are continuing our discussion with Ralph Ottey about his war memories and his life in Boston after the war, for the IBCC. Ralph, it’s lovely to see you again and thank you for agreeing to meet us and to talk some more because you were such a wonderful storyteller. Before we move on to your life after the war were there any other war memories that you wanted to tell us about?

RO: Well, I didn’t, I forgot to tell you about one of the squadrons of Mosquitoes was, were Pathfinders were based at Tattershall Park. And one that comes to mind was 109 Squadron and the leader was a New Zealander. Wing Commander Scott. And I remember that. The other squadron I just can’t recall what squadron it was but there was another squadron of Mosquitoes there. But I never had anything to do with them.

HH: And, and how did you get to know Wing Commander Scott?

RO: Well, because I think there might have been an emergency. Perhaps they wanted a driver to drive a tanker. Somebody didn’t turn up and I was loaned to just drive a tanker and fill, fill the aircraft up see. That was one of my jobs.

HH: In your capacity as a driver did you ever go and fetch fuel from a depot and then take it to the RAF stations?

RO: No. No. We had a big [pause] that place. A big tank. A big [pause] I don’t know what you would call it but we filled it with — they had, they had private company’s tankers that came and filled up all.

HH: Right.

RO: Yeah. And I would go to [pause] oh I forget what you call it but we would go there and, and get it from there. Yeah.

HH: Thank you for that.

RO: Yeah.

HH: So, we’ve, we went, last time we talked about the training that you were able to do. Bookkeeping and accounting in Staffordshire before your return to Jamaica and then you returned to Jamaica.

RO: Yeah.

HH: And you worked for a while.

RO: Yeah.

HH: In Jamaica and then you decided that you wanted to come back.

RO: Yeah.

HH: To, to Britain.

RO: To marry my girl. My fiancé. That’s what I came back for.

HH: Okay. So, tell us about your fiancé and how you had met.

RO: Oh yes. Well, this is a story that can be told a thousand times. There was a place called the Gliderdrome which still exists in Boston and it was where all the young people went to dance. There were dances on. It had, it had a roller skating some nights but dancing was definitely on the Wednesday night and on a Saturday night. And the world and his wife as young people went to the Gliderdrome if you were a serviceman. You‘ll find in Boston today there would be people who married and settled like myself who met at the Gliderdrome. And it still exists. The Gliderdrome. But not, not as a dancing place now. I think they play bingo. I think it’s a bingo hall. I think there’s a whole possibility that one of the younger people might take on and bring back dancing and concerts at the Gliderdrome. We’re hoping. But it still exists.

HH: And that’s where you met Mavis is it?

RO: That’s where I met Mavis. Yes. I met her. Well, what you used to do you had, because she was only about seventeen and she was there with another girl. Her friend. And I went up and asked her to have a dance. You can ask, you see. And it started from there. I’ve, and I asked her what her name was and she said her name was Mavis. And I said, ‘Oh, I’ve got a sister called Mavis.’ And she laughed and she said, ‘Oh, I bet you have an auntie called Daisy,’ because she had an auntie called Daisy. And I said, ‘Fortunately I have an auntie called Daisy.’ And she lived to go to Jamaica and met this Auntie Daisy so I’ll tell you that I wasn’t —

HH: How wonderful.

RO: It wasn’t just a chatting up line.

HH: Yeah.

RO: And, you know, and that was that. I met her a bit afterwards as I say. I like a dance and then it became a habit. I’d seen her at dancing and then it became that she expected me to come and see her and I expected to see her. Then after about three or four months of seeing her one night she said, ‘There’s somewhere I want to take you.’ So I said, ‘Alright.’ So we left the dance, the dance hall and we walked for about fifteen minutes and she took me to meet her mother and father. And it started from there. And then her mother and father were —

HH: And you got on well from the start?

RO: Oh yes. We got on really well there. You know, I didn’t, and I think it wasn’t that she was my girlfriend then. It was, it was later on because I was on camp and I couldn’t go. Couldn’t go over there every week because on a Saturday night I was on duty. Then it got so that if I’m not on duty, if I’m not at the Gliderdrome and I’m on duty I would ring her up, you know. It began to get like that. Then during the week if I can’t get down on the Wednesday night to the Gliderdrome then she’d perhaps ring me up. Because once I was stationed for briefly in the fire, the fire section. You see we can’t — as part of my training I could drive a fire engine. And so I was on duty at the fire engine and if I’m there I couldn’t — she’d ring the fire, I told her [unclear] she’d ring the fire station up and I would speak to her, you know. It got like that and it gradually get serious. And then —

HH: And then you took her to Scunthorpe, didn’t you?

RO: Oh yes. The people who befriended me at Scunthorpe [pause] I told them about this girlfriend and they said, ‘Oh well. Why don’t you bring her over to meet us for a weekend?’ So I said to her parents, ‘It’s alright?’ ‘Yes,’ they said, ‘Oh yes.’ So we went and spent a weekend with Aunt Lil and Uncle Arthur and we get, you know it’s, I met her in 1945. Nearly [pause] oh no. We were 1945 and we didn’t marry until early when I came back in 1949 so you know it was a long courtship. It wasn’t a shot gun period.

HH: Yeah. A long time.

RO: Yeah. I used to be at her parents’ house at Christmas in 1947 when it was a terrible winter. They had to close the camp down as I remember. I spent a few days with them in their home in Boston. And then when I went to college when I, it so happened that I used to come back to Boston every fortnight and I used to stop there and we used to go to the Gliderdrome. And it became [pause] and then when I realised that I had to [pause] when I finished college and I was going home. We talked about getting engaged because, so I said, ‘Oh, yes I will. But what I’ll do, I must go home and see my grandparents,’ who were, you know. ‘And we’ll say if, if we are still on for say six months or something like that and I can’t see my way to bring you out to Jamaica and get married out there,’ we had decided we were going to get married. I had given her an engagement ring and so on, ‘I’ll come back and and get married.’ So that’s what I did. After I was out there for about six, six months. I got a job out there but I wasn’t, I wasn’t happy. We wrote letters and there I’d got piles of letters she wrote to me. And piles. That’s right.

HH: Have you still got them?

RO: No. As a matter of fact I did a silly thing. When I left and came back I didn’t bring them. My sister got hold of them and kept my letters. And they disappeared. But I have looked because she used to write to me about two or three times a week and all that kind of thing.

HH: Yeah.

RO: Because there wasn’t any, I wasn’t able to telephone her.

HH: No. So you arrived back and then you were married. And where did you get married?

RO: Scunthorpe.

HH: In Scunthorpe.

RO: Yes. And the funny thing about it is that there was a little church that we used to pass and we’d say, ‘Oh yes. We’ll get married here.’ So we told Aunt Lil that we’d like to get married at that church. And she said, ‘Alright. You can think of us as your parents,’ you know. We’ll do all the, they did all the arrangements and everything. Then we found out that we couldn’t get married there because this was just outside the parish. So we got married at the Scunthorpe Parish Church much to, you know we didn’t really, we wanted this little church that was there but we had to get married. And it’s funny that I applied to get married and we, I was over there with, with Mavis to adhere to — and the the vicar or the priest came and to check us out that, that address we were at. From that address there. And we were there so we were alright. So we got married at the Scunthorpe Parish Church.

HH: And once, once you were married you obviously had to do something about finding a job.

RO: I think I did.

HH: And I was really interested that your, the final volume of your autobiography was called, “You’ll Never Get a Job in Boston.” So tell us about your experiences of trying to establish a career.

RO: Yeah.

HH: In Boston.

RO: Well, I, at that time war regulations were still on so you had to go to the labour, they called it the Labour Exchange at the time. You had to register as being unemployed. Right. And I went down to register and tell them who I am, you know and my qualifications I had [at the time] And I had a letter which was, I still, I think must be somewhere in my archives from the headmaster at the college, you see. And I, I showed the chap who interviewed me the letter and he looked at it and he said, ‘Oh. Was this given to you by a white man?’ So I said, well, facetiously I said to him, ‘Well, I’ll tell you something. He looked just like you.’ Whatever a white man being a surly, ‘He was just just like you.’ He said, ‘Oh well, I haven’t got anything against you, you know. But I don’t, you won’t get a job in Boston that suits. That befits your qualification.’ He said, ‘No, no Boston businessman will ever give you a job to look after their accounts.’ He said, ‘I haven’t got anything against you,’ he said, ‘No. I can see you have a first class, a HGV 1 for a driving licence,’ because of the RAF you see. ‘Oh, I think you’ll get a job as a, as a driver, you know. You’ll certainly get one.’ And I said, ‘Well, to be fair if I wanted a job as a driver I wouldn’t bother to go off to spend time at college to train as a bookkeeper. Accounts.’ I said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘I’ll try my chances with that.’ So I did. So, and I, there was a chap who used to be with the British Legion who I spoke to him about it. And he said, ‘Oh. Oh, don’t worry,’ he said. ‘Do your own thing. Apply for a job.’ He said, ‘There’s plenty of jobs in the paper. You apply for one.’ he said. So I applied for this job. Somebody wanted a bookkeeper cashier. And I thought I’d never been a cashier before but I, but I know about accounts. So, I’ll take my chances. I just applied. And lo and behold the next couple of days I, I got an invitation to to to see Mr [Buehler]. The company was called GM [Buehler] Limited to go on the Thursday to see him. Lovely. I thought that’s the first step. So I drive in. Made sure I was on time. Looking, dressed, you know presentable for interview. So when I went there Mr [Buehler] said to me, he said, he said as we were talking, ‘You didn’t, in your, in your letter to me you didn’t say you was a Jamaican.’ So, I thought to myself well that’s a funny thing. I said, ‘Well, Mr [Buehler] you didn’t ask if I was a Jamaican. You just wanted a bookkeeper and I fancied my chances.’ So he said, ‘Point taken.’ And he was with another director of the company who was the vice chairman. He was the chairman, the vice chairman and this chap, he didn’t say very much but I could see his, his eyes. They were like his eyes tried to catch my eyes. That was very, you know but he was his brother in law who was the chairman of Oldrids. The big department store in Boston. Mr, Mr Gus Isaac was his brother in law. And then they spoke to him, everything, he said, ‘Oh well, you said you had —,’ [pause] I can’t [pause] ‘Some papers from the college.’ You see. And a recommendation from the headmaster. And he said, ‘That’s quite good.’ And he said, ‘Can you excuse me?’ He had, for a minute. So I actually went in an adjoining office and within two minutes they come back and they said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what. We like, we like what we see and if you — I’ll offer you the job on the basis that for three months and if we like you we’ll make you permanent. And if you don’t like it you can leave and we’ll leave as good friends.’ You know. That type. I said, ‘Suits me fine. Yeah.’ And I came and I, he said, ‘When can you start?’ That was on a Thursday. I said, ‘Oh, well tomorrow.’ He said, ‘Oh, well not so quick [laughs] Monday. Monday will be alright.’ So, so I turned up on Monday and he introduced me to the other members of the staff and he introduced me to the chap who was leaving. The chap who was retiring and who was going to take the job and he said, ‘This chap will stay with you for a week and show, show you the ropes. What you have to do.’ When I had my first, my first responsibility was that I was the last there. There was a, there was a grandfather’s clock and I had to see to it that it’s wound up.

HH: Wound up.

RO: That was my first responsibility to start [laughs] because I was the last there. So, so I turned up on Monday on time of course and introduced me to the members of the staff [and I started from there.

HH: And how long did you stay with Mr [Buehler]?

RO: Well, this is a long story but what, what’s important is after about being there about three weeks Mr [Buehler?] called me in and said, ‘Come in. I would like to have a word with you,’ he said. I thought, ‘Crikey, I can’t imagine me doing anything out of line.’ He said, ‘Oh, well I did say to you that three months [pause] but I’ve seen enough and if it’s alright with you it’s permanent.’ So, I said, ‘Alright. It’s certainly alright with me.’ So I got the job. And I spent forty years.

HH: Gosh.

RO: I started there as a bookkeeper cashier and when I retired at sixty five I was the general manager. I became a director and I became a shareholder and that kind of thing. I grew in the company.

HH: So, tell us about the company.

RO: Well, the company was a family. A well established family business in Boston and [pause] but it was old fashioned and everything was based on the war. To survive the war. And when I came things were easing. And fortunately, when I was at college I did a lot of visiting businesses and I kept my eye open and see things that I could easily apply. So although I wasn’t part of the management I was able to say to Mr, Mr Buehler, you know. They took as improvement. And then Mr Gus, Mr Gus Isaac, the Oldrids one, he used to come. The one who used to keep an eye out watching me. He used to come and talk to me. Really friendly. And he said, ‘Now, I know you’ve been to Business College and you must have seen things and so on. And if there’s anything we can do to, you know improve and though you’re not part of the management yet, you know, you talk to Mr Gerald,’ that’s what he was called then, ‘And talk to me and we’ll look at it. We’ll look at it.’ So, I did that and Mr, Mr, Mr Isaac said to me one day, he said, ‘We’ve seen. I’ve seen enough of you and I’d like you to stay in this company. And I promise you that you will get as far in this company as your talent will take you. We’ve seen enough of you and we want you to stay.’ And that’s how it went on. And I changed the whole, although at the time I wasn’t seen as part of the management I was part of the management because the things, I mean the whole system we had these big ledgers. Big ledgers like that. Leather, leather bound and, and all that thing and I changed that to a loose leaf system and I brought in adding machines and so on. I suggested these things to Mr [Buehler] and he, yes. Then I found that I began, began to get additions to my job. You know. He was telling, Mr [Buehler] found me and, ‘Well, you know Ralph all these things you’ve brought in and you seem to have more time to do things. Would you like to take on? I’m getting older,’ because he used to do the salaries and wages. He said, ‘Do you think you could take that on?’ ‘Oh yes.’ So I take it. Then I brought in a new system. I mean he used to have these checking the calculations for paying tax and so on and I brought a slide rule. A slide rule in. I do it on every four weeks. You check with the, you know.

HH: Right.

RO: And because I’d seen that as a visitor so —

HH: Very useful.

RO: Yeah. So I got on. So, the more I am the more things I did for the company. Like, for instance I thought the office was upstairs. They had to climb the stairs and they, they used to have a machine to do the, to do labels. So the machine used to, chaps used to come up from the warehouse with, to do labels to put on the goods and they used the same machine to do the post you see. And I said to Mr [Buehler] I said ‘You can save a bit of money here.’ He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Well, what you want is a little machine up here to do the, the post and save the chap having to climb the stairs.’ I said, ‘You’ll save the costs by getting them, give them their own machine. Another little machine for the office.’ He said, ‘If only, why didn’t we think of that?’ So it was implemented. And, you know, things like that I, I did.

HH: Lots of improvements.

RO: Yeah. So he, they begin to depend on, kind of depend on me to to — so to cut a long story short I brought in [pause] by the end machine accounting and that kind, and that kind of thing. And we start getting, running out of space and so on. So he decided, yes Mr [Buehler] he hadn’t any sons. He had four daughters. So he brought in a nephew. One of these to come to succeed him. That’s what it was. And Mr [Buehler] was quite honest about it. You see, he told me, he says ‘You’re a very bright young man and, you know but I can’t, I won’t be able to offer you the job as a number one here because it’s a family business, established for long and my nephew who is just leaving the services he’s coming in and he will eventually take over from me when I retire. When I retire.’ So what he was telling me if I didn’t fancy staying I could look elsewhere for advancement. But I was quite happy. Quite happy. I said, you know, ‘We’ll see how we get on.’ And fortunately, his nephew and I we got on like a house on fire.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: And we together pulled the company from when I got there it was doing five thousand pounds a week which was a lot of money in 19’ you know, at that time. Mr [Buehler] had four daughters at public school so it must have been doing, doing alright. You see. And when I, to cut a long story short when I retired as a general manager forty years after that well we were doing, all of the businesses three quarters of a million a week.

HH: Wow.

RO: We had five cash and carries. We had a new set of businesses. We had one in Boston, one at Skegness, one at Grantham, one at Scunthorpe and one at Wisbech and one at Fakenham. Six. Six cash and carries and four or five supermarkets.

HH: Incredible. That’s, that’s huge growth.

RO: Yeah. Well, yes. So that’s when I, when I, when I retired because we, we got to the stage where Mr [Buehler] died and his nephew took over as the, as the managing, as the managing director. His wife became the chair. Became the chair, the chairperson and she didn’t want, she wasn’t keen in the business and he had no, they had no sons so she decided that we got another person who wanted to invest. To come in the company. A chap. And with him, and David Issac and myself we pulled the company. We pulled the company. So when Mrs [Buehler] decided that she’d rather sell unfortunately at the time Mr Isaac who had all these sons didn’t have the wherewithal to buy the company because it was a big company now. So we sold out to a much bigger company. A massive company. I was its general manager then and Mr [Buehler’s] nephew he joined the head of, he joined the, became a director at the big company and then he left to go and set up his own company somewhere down in Bristol. So, I, I was left with the running the, running the companies.

HH: Gosh.

RO: And I stayed until I was, did forty years.

HH: Incredible. That’s a long time.

RO: Yeah. Yeah.

HH: Tell me, Ralph so you were very successful in your career. And tell us about family and trips back to Jamaica. You had a daughter. Is that right?

RO: Oh yes. Oh yes. My daughter. My daughter Lesley. One child we have. This girl.

HH: And when was she born?

RO: She was born at the end of November 1945. That’s right. And she — no. 1949.

HH: ’49. Yeah.

RO: Yeah. 1949. And [pause] oh my daughter. She’s done exceptionally well. She didn’t, she didn’t at the time pass the eleven-plus at all. I don’t know. Everybody was surprised why she didn’t. I don’t know why she didn’t. She went to the secondary modern school called Kitwood and she was quite, quite bright. And I used to see the head mistress on the quiet to find, I never used to go to the school to see her to find out how my daughter is getting on. And she, she said to me, she said, ‘Your daughter is very bright. She could [pause] she could go far,’ you see. And I said, ‘Oh, that’s alright.’ Because my daughter was part of the young team, she didn’t, she was just dying to leave school and, and so on. So the head mistress, Miss Scorer said to me, she said, ‘Don’t you follow what she says.’ She says, ‘She will take you right down to the wire to see how far she can get.’ So when the time came for her to leave this school Miss Scorer said, ‘Her place is to go to Boston College,’ because they didn’t do A levels there, ‘And let her do her A levels there because she is quite bright and she’ll get on.’ So, when the time come my daughter said, ‘Ah yes, dad. I’ve got to leave school. I’m going to get a job.’ So, I said, ‘Yes. Is that right?’ She said, ‘Oh, actually I’m going to get a job. There’s a chap. There’s a company that sell records. I shall get a job there.’ I said, ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘Oh.’ Remembering what Miss Scorer told me, ‘Don’t worry. She’ll take you to the wire to see. Testing you.’ So I said, I said, ‘Well, of course the other side of the coin is that the headmistress says that you should go on to Boston College and do A level. Your A levels.’ She said, ‘Oh, well she would say that wouldn’t she?’ I said, ‘Yes. And I think that’s what’s going to happen.’ ‘Oh’ she says and she stomped off, you know. But she did it. She went to Boston. Then she was doing alright. I’d never been, all the time I’ve been here I didn’t have a family in Jamaica. My grandparents had died and my mother and father were still out there and some brothers and sisters. And she, they only knew her through letters so I was determined that I wouldn’t go back to Jamaica until I could afford to take my wife and daughter. And in 1966 I think I reached that stage. Just when Lesley was at the college. And so I said, ‘Alright, we’re going out to Jamaica for Christmas. Spend a long holiday.’ Six weeks. You know, out in Jamaica. I said to Lesley, ‘You’re going to meet your grandparents and your cousins and so on.’ So we went, went out and met her cousins and so on. And she, she said to me, she says, ‘Dad, I know you are worried and concerned about how I’m going to do.’ She said, ‘I’ve been out to Jamaica. I’ve met that side of my family out there,’ and she said, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll get my A levels. I’ll do it and I’ll become a teacher.’ I said, ‘Well, If that’s what you want. That’s alright.’ So that’s what she did.

HH: Did, did she enjoy Jamaica?

RO: Hmmn?

HH: Did she enjoy Jamaica?

RO: Oh yes. She was, because there were quite a number of her cousins of her age. And I think that ⸻

HH: It must have been a lot of fun for her.

RO: Yeah. And one of them, because she’s a serious thinker and most of her cousins out there was at college and she wasn’t going to be bettered. She said to me, ‘Dad, don’t worry.’

HH: That’s great.

RO: So, she came, she got back and she got her A levels and so on and went to college in Bradford. St Margaret [unclear] College. And she, she said that, at first she said that she was going to do linguistics. Then when, after she changed her mind. She said, ‘I’m going to be a general teacher.’

HH: So, did she teach in primary or high school?

RO: Oh, Lesley. She got through her training as a teacher. And she said she wanted to teach in an area where West Indians are. I said, ‘That’s alright. ’And I think I’ll go to London.’ I said, ‘Oh London.’ Fortunately for me I had a cousin. My uncle’s son who was a minister of, an Anglican priest who’d got trained over here. He went to college at, you know. A college at Cambridge. That’s right. And he, he was there and he had a [pause] he had room that if she got a job in London she could stay with him ‘til she [pause] so she applied for a job in London. At, [unclear] near Wilson High School. Secondary Modern School for Girls in Brixton. And she got it.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: So she went. Got set up in London. Fortunately for Lesley after a while she was, she was doing alright. They said to her, they said, ‘We see one of your subjects you did was drama and we haven’t got a drama — ’ What do they call it?

HH: Department.

RO: Department. ‘Would you like [unclear] to set one up?’ So, she said, ‘Of course I would.’ So she set up this.

HH: Great.

RO: And after about two years they said, ‘Now, what we want is a head of department. Do you fancy that?’ she said, ‘Of course I fancy that.’ So, she, in a short while she was a head of department and she never looked back.

HH: Amazing.

RO: After a while there was a job at St-Martin-in-the-Field High School for Girls as a Deputy Head. And my daughter applied for it, got an interview and got it.

HH: She’s done well.

RO: Yes. After about four years the Head retired at St-Martin’s-in-the-Field High School for Girls and she among ten people applied for the Headship. She got it.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: She became head of department and she changed it. She changed the school because it didn’t have a sixth form and so on. And one day she rang me at work. She said, ‘Dad, I’ve done it.’ I said, ‘What have you gone and done now?’ She said, ‘I’ve been trying to get them to give me a sixth form so that I don’t have to send my girls to another school.’ And I said, ‘What do you do now?’ She said, ‘They give me six million pounds to set up a sixth form.’ So she —

HH: Fantastic.

RO: She set up —

HH: That’s wonderful.

RO: She set up a sixth form.

HH: So, so is she still working, your daughter?

RO: Oh, no. She retired.

HH: But she retired as a head teacher.

RO: She was Head. But not only that she did so well with this school she was awarded CBE.

HH: Oh really.

RO: Oh yes.

HH: How very wonderful.

RO: Oh yeah.

HH: You must be very proud of her.

RO: Oh, yes.

HH: Do you see your family quite a lot? Do they come up to visit you?

RO: She always used to come up but since this virus she hasn’t been up.

HH: No.

RO: Since then. But she did. Oh yeah. She, she was awarded for her, and the citation is for what she did for her school.

HH: Wonderful.

RO: And for education in general. But she is still busy. She’s governor of two. Two schools now and though supposed to be retired she’s busy with that now.

HH: That’s a fantastic career she’s had.

RO: Yeah.

HH: But talking about retirement. I mean, Ralph because you since your retirement you have done such a lot. Because you retired from your, your general manager’s position at [Buehler] in 1989 was it? But then you became quite involved in the Chamber of Commerce.

RO: Chamber of Commerce. Yes.

HH: And, and then you started this other career as an author.

RO: Yes.

HH: So, you know, I mean you have been quite busy yourself.

RO: Well, yes. Yes. I [pause] when I did things I thought, I always said one of my plan to retire was not to have a plan. Do you get what I mean? I was going to see. And what I didn’t want was to have a plan to be in management. I’ve had my forty years of management but I’d want to be involved. And then one of the, you know Mr Isaac’s son who, he was [pause] he became the head of Oldrids then. And he said he, during the time he became a director of J [Buehler] Limited so I got to know him very well and he, he said to me, ‘Oh, well the Chamber of Commerce in Boston is in a bit of a [pause] [unclear] . It could do with somebody like, you, you know.’ So, I said, I said, ‘Well, I’ve got, I’ve got a, I bought a house in Jamaica now to go on holidays and I want to go spend three or four months in Jamaica on holiday. I really don’t want to.’ But he said, ‘You know, you could really jazz that thing up, you know. Put some life in it.’ So I said, ‘Alright. I’ll do it for a couple of years.’ He said, ‘Oh, we can’t pay you. Pay you much.’ I said, ‘Well, no. It’s alright. I’m not on the breadline,’ you know. So I took on a job at the Chamber of Commerce. I said I would do it for two years as their membership officer. That’s what the title was. Turned out to be something completely, almost different. I did it for twenty years.

HH: That’s a long time.

RO: Yeah. Yes. I did it for twenty years. At the same pay.

HH: But it must have made you quite well known in Boston.

RO: Oh yes. Yes. That is it. That is the reason why I, I did this book about Boston. You know the Boston Marketplace and Bargate.

HH: Bargate.

RO: Because I knew every shop. Every [pause] every manager. Almost every director [unclear]

HH: That’s wonderful. But what interested me about those, those books that you’ve written on Boston what was interesting was the way in which you remembered your early life in, in Jamaica was almost the same. You remembered all where the houses were and then all the people who occupied the houses and it was almost like you used that same model to, to write your books on Boston.

RO: Yeah.

HH: It’s a lovely way of doing it.

RO: Yeah.

HH: Was there a reason why you chose to do it like that?

RO: Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. Well, I was, I’m interested in people. You see. Because I realised which I learned at Business College is that a business is people. It’s alright having workshops and machinery. Without people there’s no business.

HH: Yeah. That’s true. Ralph, there’s something else I wanted to ask you in addition to all the other things that have kept you so busy. Did you ever sort of link up with other veterans who had served in the RAF? Have you? Have you kept in touch with any of the people that you served with? Have you?

RO: Well, yes. I had a friend named Roy March. We met at [pause] when we were learning to be, to be drivers at Training School in 1944. That’s right. Yeah. At, down in Wiltshire. Melksham. And we remained friends until he died about, he was two years older than me and he died about three, three years ago.

HH: Okay.

RO: And we’ve been friends all — he’s the nearest, he’s the nearest thing I had to [pause] outside my family. We had a thing that we, we developed. He never sold me anything and I never sell him anything. If I had something and he, and I can do without it I gave it to him. And the same with me. We never. There hasn’t been anything that I’ve ever bought from him in all those years. And neither, if I had something and Roy liked it and I can part with it he had it and the same.

HH: Wonderful. In, in one of your volumes of autobiography you noted that some other Jamaicans who had served in the RAF also married Boston women.

RO: Yeah.

HH: Now, why didn’t they settle in Boston? Where did they go?

RO: Well, not, none of them really. This friend of mine, Roy March he settled for a while in Boston. When I came back and got married he was in London. He was a, he at that time he was working as a motor, motor engineer. That’s what he went to learn motor engineering. The fellow from — at Scotland Yard. That’s right. And he was at Scotland Yard. And then he left. When I came back to Boston he left. He’d married and came back to Boston for about three or four years. But he didn’t, he couldn’t settle in Boston because he was, he was a town man. He was brought up in Kingston. He went to school in Kingston. I’m a village boy. Very much a village boy. Boston pace suits me. It didn’t suit him so he was always rushing off to London and so he went back to London and joined the Civil Service. And then he retired and went back and set up and became quite a good business man out in Jamaica until he died. Yeah.

HH: There’s a last question I want to ask you before we conclude because I think it’s time for you to have your photograph taken. Which is, all the way through your volumes of biography you talk about how you were learning. ‘I was learning. I was learning.’

RO: Yeah. Yeah.

HH: ‘I was learning.’ And what I want to ask you as a final question is you’ve obviously learned a lot in order to survive and to have a successful career. What do you think you think you might have taught people though? You learned a lot but what do you think you taught people who came in to contact with you?

RO: Well, I don’t know whether I I have. In Boston I had many acquaintances but I’ve, well truly I have real friends, both male and female. They’ve always been kind of long term people. Not many. But they’re long term. For instance I have a friend [pause] Mrs Hopkins. And she was the one who kind of pushed me. She’s a solicitor and I met her when we did a job for the Chamber. She was President of the Junior Chamber. She’s much younger. She’s forty years younger than I am but we seem to get along. We did this job and she’s never done [pause] in the Chamber of Commerce while she was President of the Junior Chamber she never got on with anybody as she got on well with me. And from then on it’s just been a friendship. And between you and me she gave, she knew that I like books and detective stories and I always know what Christmas present I’m going to get, or whatever present is going to be. A detective story. A detective story. So I’ve got piles of books [laughs]

HH: Well, perhaps that’s a very good point to to conclude this interview and I would like to thank you again so much for sharing these memories and these stories of your quite extraordinary life.

RO: Is that right?

HH: So, thank you very much.

[recording paused]

RO: Leave you know, I told you about [unclear] Yeah, who told me that if I behaved in England as I would behave in Little London where my uncles and cousins and grandparents was, how things would be alright because by and large he says most English people who he has dealt with are fair minded people. Fair minded. And he said that although he had had to take a hotel to court because of his colour. He said that he doesn’t say that people in England are all colour prejudiced. He said no. By and large people are fair minded. And if you behave in England as you would behave in your village you’ll be alright. And I’ve done that.

HH: And did it work for you?

RO: Oh yes. It worked for me. I’ve, I’ve got lots of acquaintances and friends and people. I mean the Isaacs and [Buehlers]. The family. I’ll tell you I, when I was writing this second book, a book about Bargate we thought we’ll go a bit upmarket and have a nice book presentation and so on. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to go, get myself, as it were indebted. To take the risk. And I was talking to one of the Isaacs who, and I told him I said you know [unclear] for that money out to make sure that I [pause] And he said, he didn’t say anything and I went home. And about a couple of hours later he, the doorbell rang. And he turned up with a cheque for a thousand pounds.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: Towards it. Yeah. He said, ‘I think you need help.’ And that’s —

HH: Great.

RO: No problem. A thousand pound.

HH: A nice story.

RO: And another one of the Isaacs said, ‘I’m selling a business.’ He had a business, ‘When I get the money in July,’ he said, ‘I’ll send you a cheque towards it.’ He sent me a cheque for two thousand pounds.

HH: Very generous.

RO: You see. I had the money to do that book.

HH: I’m pleased that you did because it’s, it’s lovely that you produced all these books.

RO: Yeah.

HH: And we hope that it won’t be stopping any time soon. We’ll help you to get some more done.

RO: Oh yeah.

HH: Thank you Ralph so much.

RO: You see, you keep me talking.

RO: Well, I didn’t, I forgot to tell you about one of the squadrons of Mosquitoes was, were Pathfinders were based at Tattershall Park. And one that comes to mind was 109 Squadron and the leader was a New Zealander. Wing Commander Scott. And I remember that. The other squadron I just can’t recall what squadron it was but there was another squadron of Mosquitoes there. But I never had anything to do with them.

HH: And, and how did you get to know Wing Commander Scott?

RO: Well, because I think there might have been an emergency. Perhaps they wanted a driver to drive a tanker. Somebody didn’t turn up and I was loaned to just drive a tanker and fill, fill the aircraft up see. That was one of my jobs.

HH: In your capacity as a driver did you ever go and fetch fuel from a depot and then take it to the RAF stations?

RO: No. No. We had a big [pause] that place. A big tank. A big [pause] I don’t know what you would call it but we filled it with — they had, they had private company’s tankers that came and filled up all.

HH: Right.

RO: Yeah. And I would go to [pause] oh I forget what you call it but we would go there and, and get it from there. Yeah.

HH: Thank you for that.

RO: Yeah.

HH: So, we’ve, we went, last time we talked about the training that you were able to do. Bookkeeping and accounting in Staffordshire before your return to Jamaica and then you returned to Jamaica.

RO: Yeah.

HH: And you worked for a while.

RO: Yeah.

HH: In Jamaica and then you decided that you wanted to come back.

RO: Yeah.

HH: To, to Britain.

RO: To marry my girl. My fiancé. That’s what I came back for.

HH: Okay. So, tell us about your fiancé and how you had met.

RO: Oh yes. Well, this is a story that can be told a thousand times. There was a place called the Gliderdrome which still exists in Boston and it was where all the young people went to dance. There were dances on. It had, it had a roller skating some nights but dancing was definitely on the Wednesday night and on a Saturday night. And the world and his wife as young people went to the Gliderdrome if you were a serviceman. You‘ll find in Boston today there would be people who married and settled like myself who met at the Gliderdrome. And it still exists. The Gliderdrome. But not, not as a dancing place now. I think they play bingo. I think it’s a bingo hall. I think there’s a whole possibility that one of the younger people might take on and bring back dancing and concerts at the Gliderdrome. We’re hoping. But it still exists.

HH: And that’s where you met Mavis is it?

RO: That’s where I met Mavis. Yes. I met her. Well, what you used to do you had, because she was only about seventeen and she was there with another girl. Her friend. And I went up and asked her to have a dance. You can ask, you see. And it started from there. I’ve, and I asked her what her name was and she said her name was Mavis. And I said, ‘Oh, I’ve got a sister called Mavis.’ And she laughed and she said, ‘Oh, I bet you have an auntie called Daisy,’ because she had an auntie called Daisy. And I said, ‘Fortunately I have an auntie called Daisy.’ And she lived to go to Jamaica and met this Auntie Daisy so I’ll tell you that I wasn’t —

HH: How wonderful.

RO: It wasn’t just a chatting up line.

HH: Yeah.

RO: And, you know, and that was that. I met her a bit afterwards as I say. I like a dance and then it became a habit. I’d seen her at dancing and then it became that she expected me to come and see her and I expected to see her. Then after about three or four months of seeing her one night she said, ‘There’s somewhere I want to take you.’ So I said, ‘Alright.’ So we left the dance, the dance hall and we walked for about fifteen minutes and she took me to meet her mother and father. And it started from there. And then her mother and father were —

HH: And you got on well from the start?

RO: Oh yes. We got on really well there. You know, I didn’t, and I think it wasn’t that she was my girlfriend then. It was, it was later on because I was on camp and I couldn’t go. Couldn’t go over there every week because on a Saturday night I was on duty. Then it got so that if I’m not on duty, if I’m not at the Gliderdrome and I’m on duty I would ring her up, you know. It began to get like that. Then during the week if I can’t get down on the Wednesday night to the Gliderdrome then she’d perhaps ring me up. Because once I was stationed for briefly in the fire, the fire section. You see we can’t — as part of my training I could drive a fire engine. And so I was on duty at the fire engine and if I’m there I couldn’t — she’d ring the fire, I told her [unclear] she’d ring the fire station up and I would speak to her, you know. It got like that and it gradually get serious. And then —

HH: And then you took her to Scunthorpe, didn’t you?

RO: Oh yes. The people who befriended me at Scunthorpe [pause] I told them about this girlfriend and they said, ‘Oh well. Why don’t you bring her over to meet us for a weekend?’ So I said to her parents, ‘It’s alright?’ ‘Yes,’ they said, ‘Oh yes.’ So we went and spent a weekend with Aunt Lil and Uncle Arthur and we get, you know it’s, I met her in 1945. Nearly [pause] oh no. We were 1945 and we didn’t marry until early when I came back in 1949 so you know it was a long courtship. It wasn’t a shot gun period.

HH: Yeah. A long time.

RO: Yeah. I used to be at her parents’ house at Christmas in 1947 when it was a terrible winter. They had to close the camp down as I remember. I spent a few days with them in their home in Boston. And then when I went to college when I, it so happened that I used to come back to Boston every fortnight and I used to stop there and we used to go to the Gliderdrome. And it became [pause] and then when I realised that I had to [pause] when I finished college and I was going home. We talked about getting engaged because, so I said, ‘Oh, yes I will. But what I’ll do, I must go home and see my grandparents,’ who were, you know. ‘And we’ll say if, if we are still on for say six months or something like that and I can’t see my way to bring you out to Jamaica and get married out there,’ we had decided we were going to get married. I had given her an engagement ring and so on, ‘I’ll come back and and get married.’ So that’s what I did. After I was out there for about six, six months. I got a job out there but I wasn’t, I wasn’t happy. We wrote letters and there I’d got piles of letters she wrote to me. And piles. That’s right.

HH: Have you still got them?

RO: No. As a matter of fact I did a silly thing. When I left and came back I didn’t bring them. My sister got hold of them and kept my letters. And they disappeared. But I have looked because she used to write to me about two or three times a week and all that kind of thing.

HH: Yeah.

RO: Because there wasn’t any, I wasn’t able to telephone her.

HH: No. So you arrived back and then you were married. And where did you get married?

RO: Scunthorpe.

HH: In Scunthorpe.

RO: Yes. And the funny thing about it is that there was a little church that we used to pass and we’d say, ‘Oh yes. We’ll get married here.’ So we told Aunt Lil that we’d like to get married at that church. And she said, ‘Alright. You can think of us as your parents,’ you know. We’ll do all the, they did all the arrangements and everything. Then we found out that we couldn’t get married there because this was just outside the parish. So we got married at the Scunthorpe Parish Church much to, you know we didn’t really, we wanted this little church that was there but we had to get married. And it’s funny that I applied to get married and we, I was over there with, with Mavis to adhere to — and the the vicar or the priest came and to check us out that, that address we were at. From that address there. And we were there so we were alright. So we got married at the Scunthorpe Parish Church.

HH: And once, once you were married you obviously had to do something about finding a job.

RO: I think I did.

HH: And I was really interested that your, the final volume of your autobiography was called, “You’ll Never Get a Job in Boston.” So tell us about your experiences of trying to establish a career.

RO: Yeah.

HH: In Boston.

RO: Well, I, at that time war regulations were still on so you had to go to the labour, they called it the Labour Exchange at the time. You had to register as being unemployed. Right. And I went down to register and tell them who I am, you know and my qualifications I had [at the time] And I had a letter which was, I still, I think must be somewhere in my archives from the headmaster at the college, you see. And I, I showed the chap who interviewed me the letter and he looked at it and he said, ‘Oh. Was this given to you by a white man?’ So I said, well, facetiously I said to him, ‘Well, I’ll tell you something. He looked just like you.’ Whatever a white man being a surly, ‘He was just just like you.’ He said, ‘Oh well, I haven’t got anything against you, you know. But I don’t, you won’t get a job in Boston that suits. That befits your qualification.’ He said, ‘No, no Boston businessman will ever give you a job to look after their accounts.’ He said, ‘I haven’t got anything against you,’ he said, ‘No. I can see you have a first class, a HGV 1 for a driving licence,’ because of the RAF you see. ‘Oh, I think you’ll get a job as a, as a driver, you know. You’ll certainly get one.’ And I said, ‘Well, to be fair if I wanted a job as a driver I wouldn’t bother to go off to spend time at college to train as a bookkeeper. Accounts.’ I said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘I’ll try my chances with that.’ So I did. So, and I, there was a chap who used to be with the British Legion who I spoke to him about it. And he said, ‘Oh. Oh, don’t worry,’ he said. ‘Do your own thing. Apply for a job.’ He said, ‘There’s plenty of jobs in the paper. You apply for one.’ he said. So I applied for this job. Somebody wanted a bookkeeper cashier. And I thought I’d never been a cashier before but I, but I know about accounts. So, I’ll take my chances. I just applied. And lo and behold the next couple of days I, I got an invitation to to to see Mr [Buehler]. The company was called GM [Buehler] Limited to go on the Thursday to see him. Lovely. I thought that’s the first step. So I drive in. Made sure I was on time. Looking, dressed, you know presentable for interview. So when I went there Mr [Buehler] said to me, he said, he said as we were talking, ‘You didn’t, in your, in your letter to me you didn’t say you was a Jamaican.’ So, I thought to myself well that’s a funny thing. I said, ‘Well, Mr [Buehler] you didn’t ask if I was a Jamaican. You just wanted a bookkeeper and I fancied my chances.’ So he said, ‘Point taken.’ And he was with another director of the company who was the vice chairman. He was the chairman, the vice chairman and this chap, he didn’t say very much but I could see his, his eyes. They were like his eyes tried to catch my eyes. That was very, you know but he was his brother in law who was the chairman of Oldrids. The big department store in Boston. Mr, Mr Gus Isaac was his brother in law. And then they spoke to him, everything, he said, ‘Oh well, you said you had —,’ [pause] I can’t [pause] ‘Some papers from the college.’ You see. And a recommendation from the headmaster. And he said, ‘That’s quite good.’ And he said, ‘Can you excuse me?’ He had, for a minute. So I actually went in an adjoining office and within two minutes they come back and they said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you what. We like, we like what we see and if you — I’ll offer you the job on the basis that for three months and if we like you we’ll make you permanent. And if you don’t like it you can leave and we’ll leave as good friends.’ You know. That type. I said, ‘Suits me fine. Yeah.’ And I came and I, he said, ‘When can you start?’ That was on a Thursday. I said, ‘Oh, well tomorrow.’ He said, ‘Oh, well not so quick [laughs] Monday. Monday will be alright.’ So, so I turned up on Monday and he introduced me to the other members of the staff and he introduced me to the chap who was leaving. The chap who was retiring and who was going to take the job and he said, ‘This chap will stay with you for a week and show, show you the ropes. What you have to do.’ When I had my first, my first responsibility was that I was the last there. There was a, there was a grandfather’s clock and I had to see to it that it’s wound up.

HH: Wound up.

RO: That was my first responsibility to start [laughs] because I was the last there. So, so I turned up on Monday on time of course and introduced me to the members of the staff [and I started from there.

HH: And how long did you stay with Mr [Buehler]?

RO: Well, this is a long story but what, what’s important is after about being there about three weeks Mr [Buehler?] called me in and said, ‘Come in. I would like to have a word with you,’ he said. I thought, ‘Crikey, I can’t imagine me doing anything out of line.’ He said, ‘Oh, well I did say to you that three months [pause] but I’ve seen enough and if it’s alright with you it’s permanent.’ So, I said, ‘Alright. It’s certainly alright with me.’ So I got the job. And I spent forty years.

HH: Gosh.

RO: I started there as a bookkeeper cashier and when I retired at sixty five I was the general manager. I became a director and I became a shareholder and that kind of thing. I grew in the company.

HH: So, tell us about the company.

RO: Well, the company was a family. A well established family business in Boston and [pause] but it was old fashioned and everything was based on the war. To survive the war. And when I came things were easing. And fortunately, when I was at college I did a lot of visiting businesses and I kept my eye open and see things that I could easily apply. So although I wasn’t part of the management I was able to say to Mr, Mr Buehler, you know. They took as improvement. And then Mr Gus, Mr Gus Isaac, the Oldrids one, he used to come. The one who used to keep an eye out watching me. He used to come and talk to me. Really friendly. And he said, ‘Now, I know you’ve been to Business College and you must have seen things and so on. And if there’s anything we can do to, you know improve and though you’re not part of the management yet, you know, you talk to Mr Gerald,’ that’s what he was called then, ‘And talk to me and we’ll look at it. We’ll look at it.’ So, I did that and Mr, Mr, Mr Isaac said to me one day, he said, ‘We’ve seen. I’ve seen enough of you and I’d like you to stay in this company. And I promise you that you will get as far in this company as your talent will take you. We’ve seen enough of you and we want you to stay.’ And that’s how it went on. And I changed the whole, although at the time I wasn’t seen as part of the management I was part of the management because the things, I mean the whole system we had these big ledgers. Big ledgers like that. Leather, leather bound and, and all that thing and I changed that to a loose leaf system and I brought in adding machines and so on. I suggested these things to Mr [Buehler] and he, yes. Then I found that I began, began to get additions to my job. You know. He was telling, Mr [Buehler] found me and, ‘Well, you know Ralph all these things you’ve brought in and you seem to have more time to do things. Would you like to take on? I’m getting older,’ because he used to do the salaries and wages. He said, ‘Do you think you could take that on?’ ‘Oh yes.’ So I take it. Then I brought in a new system. I mean he used to have these checking the calculations for paying tax and so on and I brought a slide rule. A slide rule in. I do it on every four weeks. You check with the, you know.

HH: Right.

RO: And because I’d seen that as a visitor so —

HH: Very useful.

RO: Yeah. So I got on. So, the more I am the more things I did for the company. Like, for instance I thought the office was upstairs. They had to climb the stairs and they, they used to have a machine to do the, to do labels. So the machine used to, chaps used to come up from the warehouse with, to do labels to put on the goods and they used the same machine to do the post you see. And I said to Mr [Buehler] I said ‘You can save a bit of money here.’ He said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Well, what you want is a little machine up here to do the, the post and save the chap having to climb the stairs.’ I said, ‘You’ll save the costs by getting them, give them their own machine. Another little machine for the office.’ He said, ‘If only, why didn’t we think of that?’ So it was implemented. And, you know, things like that I, I did.

HH: Lots of improvements.

RO: Yeah. So he, they begin to depend on, kind of depend on me to to — so to cut a long story short I brought in [pause] by the end machine accounting and that kind, and that kind of thing. And we start getting, running out of space and so on. So he decided, yes Mr [Buehler] he hadn’t any sons. He had four daughters. So he brought in a nephew. One of these to come to succeed him. That’s what it was. And Mr [Buehler] was quite honest about it. You see, he told me, he says ‘You’re a very bright young man and, you know but I can’t, I won’t be able to offer you the job as a number one here because it’s a family business, established for long and my nephew who is just leaving the services he’s coming in and he will eventually take over from me when I retire. When I retire.’ So what he was telling me if I didn’t fancy staying I could look elsewhere for advancement. But I was quite happy. Quite happy. I said, you know, ‘We’ll see how we get on.’ And fortunately, his nephew and I we got on like a house on fire.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: And we together pulled the company from when I got there it was doing five thousand pounds a week which was a lot of money in 19’ you know, at that time. Mr [Buehler] had four daughters at public school so it must have been doing, doing alright. You see. And when I, to cut a long story short when I retired as a general manager forty years after that well we were doing, all of the businesses three quarters of a million a week.

HH: Wow.

RO: We had five cash and carries. We had a new set of businesses. We had one in Boston, one at Skegness, one at Grantham, one at Scunthorpe and one at Wisbech and one at Fakenham. Six. Six cash and carries and four or five supermarkets.

HH: Incredible. That’s, that’s huge growth.

RO: Yeah. Well, yes. So that’s when I, when I, when I retired because we, we got to the stage where Mr [Buehler] died and his nephew took over as the, as the managing, as the managing director. His wife became the chair. Became the chair, the chairperson and she didn’t want, she wasn’t keen in the business and he had no, they had no sons so she decided that we got another person who wanted to invest. To come in the company. A chap. And with him, and David Issac and myself we pulled the company. We pulled the company. So when Mrs [Buehler] decided that she’d rather sell unfortunately at the time Mr Isaac who had all these sons didn’t have the wherewithal to buy the company because it was a big company now. So we sold out to a much bigger company. A massive company. I was its general manager then and Mr [Buehler’s] nephew he joined the head of, he joined the, became a director at the big company and then he left to go and set up his own company somewhere down in Bristol. So, I, I was left with the running the, running the companies.

HH: Gosh.

RO: And I stayed until I was, did forty years.

HH: Incredible. That’s a long time.

RO: Yeah. Yeah.

HH: Tell me, Ralph so you were very successful in your career. And tell us about family and trips back to Jamaica. You had a daughter. Is that right?

RO: Oh yes. Oh yes. My daughter. My daughter Lesley. One child we have. This girl.

HH: And when was she born?

RO: She was born at the end of November 1945. That’s right. And she — no. 1949.

HH: ’49. Yeah.

RO: Yeah. 1949. And [pause] oh my daughter. She’s done exceptionally well. She didn’t, she didn’t at the time pass the eleven-plus at all. I don’t know. Everybody was surprised why she didn’t. I don’t know why she didn’t. She went to the secondary modern school called Kitwood and she was quite, quite bright. And I used to see the head mistress on the quiet to find, I never used to go to the school to see her to find out how my daughter is getting on. And she, she said to me, she said, ‘Your daughter is very bright. She could [pause] she could go far,’ you see. And I said, ‘Oh, that’s alright.’ Because my daughter was part of the young team, she didn’t, she was just dying to leave school and, and so on. So the head mistress, Miss Scorer said to me, she said, ‘Don’t you follow what she says.’ She says, ‘She will take you right down to the wire to see how far she can get.’ So when the time came for her to leave this school Miss Scorer said, ‘Her place is to go to Boston College,’ because they didn’t do A levels there, ‘And let her do her A levels there because she is quite bright and she’ll get on.’ So, when the time come my daughter said, ‘Ah yes, dad. I’ve got to leave school. I’m going to get a job.’ So, I said, ‘Yes. Is that right?’ She said, ‘Oh, actually I’m going to get a job. There’s a chap. There’s a company that sell records. I shall get a job there.’ I said, ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘Oh.’ Remembering what Miss Scorer told me, ‘Don’t worry. She’ll take you to the wire to see. Testing you.’ So I said, I said, ‘Well, of course the other side of the coin is that the headmistress says that you should go on to Boston College and do A level. Your A levels.’ She said, ‘Oh, well she would say that wouldn’t she?’ I said, ‘Yes. And I think that’s what’s going to happen.’ ‘Oh’ she says and she stomped off, you know. But she did it. She went to Boston. Then she was doing alright. I’d never been, all the time I’ve been here I didn’t have a family in Jamaica. My grandparents had died and my mother and father were still out there and some brothers and sisters. And she, they only knew her through letters so I was determined that I wouldn’t go back to Jamaica until I could afford to take my wife and daughter. And in 1966 I think I reached that stage. Just when Lesley was at the college. And so I said, ‘Alright, we’re going out to Jamaica for Christmas. Spend a long holiday.’ Six weeks. You know, out in Jamaica. I said to Lesley, ‘You’re going to meet your grandparents and your cousins and so on.’ So we went, went out and met her cousins and so on. And she, she said to me, she says, ‘Dad, I know you are worried and concerned about how I’m going to do.’ She said, ‘I’ve been out to Jamaica. I’ve met that side of my family out there,’ and she said, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll get my A levels. I’ll do it and I’ll become a teacher.’ I said, ‘Well, If that’s what you want. That’s alright.’ So that’s what she did.

HH: Did, did she enjoy Jamaica?

RO: Hmmn?

HH: Did she enjoy Jamaica?

RO: Oh yes. She was, because there were quite a number of her cousins of her age. And I think that ⸻

HH: It must have been a lot of fun for her.

RO: Yeah. And one of them, because she’s a serious thinker and most of her cousins out there was at college and she wasn’t going to be bettered. She said to me, ‘Dad, don’t worry.’

HH: That’s great.

RO: So, she came, she got back and she got her A levels and so on and went to college in Bradford. St Margaret [unclear] College. And she, she said that, at first she said that she was going to do linguistics. Then when, after she changed her mind. She said, ‘I’m going to be a general teacher.’

HH: So, did she teach in primary or high school?

RO: Oh, Lesley. She got through her training as a teacher. And she said she wanted to teach in an area where West Indians are. I said, ‘That’s alright. ’And I think I’ll go to London.’ I said, ‘Oh London.’ Fortunately for me I had a cousin. My uncle’s son who was a minister of, an Anglican priest who’d got trained over here. He went to college at, you know. A college at Cambridge. That’s right. And he, he was there and he had a [pause] he had room that if she got a job in London she could stay with him ‘til she [pause] so she applied for a job in London. At, [unclear] near Wilson High School. Secondary Modern School for Girls in Brixton. And she got it.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: So she went. Got set up in London. Fortunately for Lesley after a while she was, she was doing alright. They said to her, they said, ‘We see one of your subjects you did was drama and we haven’t got a drama — ’ What do they call it?

HH: Department.

RO: Department. ‘Would you like [unclear] to set one up?’ So, she said, ‘Of course I would.’ So she set up this.

HH: Great.

RO: And after about two years they said, ‘Now, what we want is a head of department. Do you fancy that?’ she said, ‘Of course I fancy that.’ So, she, in a short while she was a head of department and she never looked back.

HH: Amazing.

RO: After a while there was a job at St-Martin-in-the-Field High School for Girls as a Deputy Head. And my daughter applied for it, got an interview and got it.

HH: She’s done well.

RO: Yes. After about four years the Head retired at St-Martin’s-in-the-Field High School for Girls and she among ten people applied for the Headship. She got it.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: She became head of department and she changed it. She changed the school because it didn’t have a sixth form and so on. And one day she rang me at work. She said, ‘Dad, I’ve done it.’ I said, ‘What have you gone and done now?’ She said, ‘I’ve been trying to get them to give me a sixth form so that I don’t have to send my girls to another school.’ And I said, ‘What do you do now?’ She said, ‘They give me six million pounds to set up a sixth form.’ So she —

HH: Fantastic.

RO: She set up —

HH: That’s wonderful.

RO: She set up a sixth form.

HH: So, so is she still working, your daughter?

RO: Oh, no. She retired.

HH: But she retired as a head teacher.

RO: She was Head. But not only that she did so well with this school she was awarded CBE.

HH: Oh really.

RO: Oh yes.

HH: How very wonderful.

RO: Oh yeah.

HH: You must be very proud of her.

RO: Oh, yes.

HH: Do you see your family quite a lot? Do they come up to visit you?

RO: She always used to come up but since this virus she hasn’t been up.

HH: No.

RO: Since then. But she did. Oh yeah. She, she was awarded for her, and the citation is for what she did for her school.

HH: Wonderful.

RO: And for education in general. But she is still busy. She’s governor of two. Two schools now and though supposed to be retired she’s busy with that now.

HH: That’s a fantastic career she’s had.

RO: Yeah.

HH: But talking about retirement. I mean, Ralph because you since your retirement you have done such a lot. Because you retired from your, your general manager’s position at [Buehler] in 1989 was it? But then you became quite involved in the Chamber of Commerce.

RO: Chamber of Commerce. Yes.

HH: And, and then you started this other career as an author.

RO: Yes.

HH: So, you know, I mean you have been quite busy yourself.

RO: Well, yes. Yes. I [pause] when I did things I thought, I always said one of my plan to retire was not to have a plan. Do you get what I mean? I was going to see. And what I didn’t want was to have a plan to be in management. I’ve had my forty years of management but I’d want to be involved. And then one of the, you know Mr Isaac’s son who, he was [pause] he became the head of Oldrids then. And he said he, during the time he became a director of J [Buehler] Limited so I got to know him very well and he, he said to me, ‘Oh, well the Chamber of Commerce in Boston is in a bit of a [pause] [unclear] . It could do with somebody like, you, you know.’ So, I said, I said, ‘Well, I’ve got, I’ve got a, I bought a house in Jamaica now to go on holidays and I want to go spend three or four months in Jamaica on holiday. I really don’t want to.’ But he said, ‘You know, you could really jazz that thing up, you know. Put some life in it.’ So I said, ‘Alright. I’ll do it for a couple of years.’ He said, ‘Oh, we can’t pay you. Pay you much.’ I said, ‘Well, no. It’s alright. I’m not on the breadline,’ you know. So I took on a job at the Chamber of Commerce. I said I would do it for two years as their membership officer. That’s what the title was. Turned out to be something completely, almost different. I did it for twenty years.

HH: That’s a long time.

RO: Yeah. Yes. I did it for twenty years. At the same pay.

HH: But it must have made you quite well known in Boston.

RO: Oh yes. Yes. That is it. That is the reason why I, I did this book about Boston. You know the Boston Marketplace and Bargate.

HH: Bargate.

RO: Because I knew every shop. Every [pause] every manager. Almost every director [unclear]

HH: That’s wonderful. But what interested me about those, those books that you’ve written on Boston what was interesting was the way in which you remembered your early life in, in Jamaica was almost the same. You remembered all where the houses were and then all the people who occupied the houses and it was almost like you used that same model to, to write your books on Boston.

RO: Yeah.

HH: It’s a lovely way of doing it.

RO: Yeah.

HH: Was there a reason why you chose to do it like that?

RO: Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. Well, I was, I’m interested in people. You see. Because I realised which I learned at Business College is that a business is people. It’s alright having workshops and machinery. Without people there’s no business.

HH: Yeah. That’s true. Ralph, there’s something else I wanted to ask you in addition to all the other things that have kept you so busy. Did you ever sort of link up with other veterans who had served in the RAF? Have you? Have you kept in touch with any of the people that you served with? Have you?

RO: Well, yes. I had a friend named Roy March. We met at [pause] when we were learning to be, to be drivers at Training School in 1944. That’s right. Yeah. At, down in Wiltshire. Melksham. And we remained friends until he died about, he was two years older than me and he died about three, three years ago.

HH: Okay.

RO: And we’ve been friends all — he’s the nearest, he’s the nearest thing I had to [pause] outside my family. We had a thing that we, we developed. He never sold me anything and I never sell him anything. If I had something and he, and I can do without it I gave it to him. And the same with me. We never. There hasn’t been anything that I’ve ever bought from him in all those years. And neither, if I had something and Roy liked it and I can part with it he had it and the same.

HH: Wonderful. In, in one of your volumes of autobiography you noted that some other Jamaicans who had served in the RAF also married Boston women.

RO: Yeah.

HH: Now, why didn’t they settle in Boston? Where did they go?

RO: Well, not, none of them really. This friend of mine, Roy March he settled for a while in Boston. When I came back and got married he was in London. He was a, he at that time he was working as a motor, motor engineer. That’s what he went to learn motor engineering. The fellow from — at Scotland Yard. That’s right. And he was at Scotland Yard. And then he left. When I came back to Boston he left. He’d married and came back to Boston for about three or four years. But he didn’t, he couldn’t settle in Boston because he was, he was a town man. He was brought up in Kingston. He went to school in Kingston. I’m a village boy. Very much a village boy. Boston pace suits me. It didn’t suit him so he was always rushing off to London and so he went back to London and joined the Civil Service. And then he retired and went back and set up and became quite a good business man out in Jamaica until he died. Yeah.

HH: There’s a last question I want to ask you before we conclude because I think it’s time for you to have your photograph taken. Which is, all the way through your volumes of biography you talk about how you were learning. ‘I was learning. I was learning.’

RO: Yeah. Yeah.

HH: ‘I was learning.’ And what I want to ask you as a final question is you’ve obviously learned a lot in order to survive and to have a successful career. What do you think you think you might have taught people though? You learned a lot but what do you think you taught people who came in to contact with you?

RO: Well, I don’t know whether I I have. In Boston I had many acquaintances but I’ve, well truly I have real friends, both male and female. They’ve always been kind of long term people. Not many. But they’re long term. For instance I have a friend [pause] Mrs Hopkins. And she was the one who kind of pushed me. She’s a solicitor and I met her when we did a job for the Chamber. She was President of the Junior Chamber. She’s much younger. She’s forty years younger than I am but we seem to get along. We did this job and she’s never done [pause] in the Chamber of Commerce while she was President of the Junior Chamber she never got on with anybody as she got on well with me. And from then on it’s just been a friendship. And between you and me she gave, she knew that I like books and detective stories and I always know what Christmas present I’m going to get, or whatever present is going to be. A detective story. A detective story. So I’ve got piles of books [laughs]

HH: Well, perhaps that’s a very good point to to conclude this interview and I would like to thank you again so much for sharing these memories and these stories of your quite extraordinary life.

RO: Is that right?

HH: So, thank you very much.

[recording paused]

RO: Leave you know, I told you about [unclear] Yeah, who told me that if I behaved in England as I would behave in Little London where my uncles and cousins and grandparents was, how things would be alright because by and large he says most English people who he has dealt with are fair minded people. Fair minded. And he said that although he had had to take a hotel to court because of his colour. He said that he doesn’t say that people in England are all colour prejudiced. He said no. By and large people are fair minded. And if you behave in England as you would behave in your village you’ll be alright. And I’ve done that.

HH: And did it work for you?

RO: Oh yes. It worked for me. I’ve, I’ve got lots of acquaintances and friends and people. I mean the Isaacs and [Buehlers]. The family. I’ll tell you I, when I was writing this second book, a book about Bargate we thought we’ll go a bit upmarket and have a nice book presentation and so on. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to go, get myself, as it were indebted. To take the risk. And I was talking to one of the Isaacs who, and I told him I said you know [unclear] for that money out to make sure that I [pause] And he said, he didn’t say anything and I went home. And about a couple of hours later he, the doorbell rang. And he turned up with a cheque for a thousand pounds.

HH: Fantastic.

RO: Towards it. Yeah. He said, ‘I think you need help.’ And that’s —

HH: Great.

RO: No problem. A thousand pound.

HH: A nice story.

RO: And another one of the Isaacs said, ‘I’m selling a business.’ He had a business, ‘When I get the money in July,’ he said, ‘I’ll send you a cheque towards it.’ He sent me a cheque for two thousand pounds.

HH: Very generous.

RO: You see. I had the money to do that book.

HH: I’m pleased that you did because it’s, it’s lovely that you produced all these books.

RO: Yeah.

HH: And we hope that it won’t be stopping any time soon. We’ll help you to get some more done.

RO: Oh yeah.

HH: Thank you Ralph so much.

RO: You see, you keep me talking.

Collection

Citation

Heather Hughes, “Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. Two,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 22, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/27256.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.