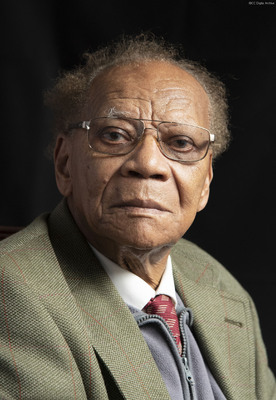

Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. One

Title

Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. One

Description

Ralph Ottey was born in Jamaica in 1924. Raised by his grandparents, he describes his education and the family hopes that he would become a teacher. He left school at 16 and a half but was too young to attend teaching college so worked for his uncle from 1940 to 1942. Ralph wanted to be an air gunner. He explains the variety of jobs he had before attending an RAF recruitment event in 1943. He applied to join but had to wait to take the entrance exams. He enlisted to become a wireless operator/air gunner. He sailed in a convoy from New York to Liverpool. On arrival he was posted to RAF Filey for 13 weeks basic training. Having been told that there was no demand for new wireless operator/air gunners he was assigned the role of motor transport driver. He explains that whilst at RAF Filey he met who were to become his adopted parents. He was posted to No. 1 RAF Transport School at RAF Melksham. He passed out as an aircraftman first class driver (AC1) on completing the 13-week driving course. Finally posted to RAF Woodhall Spa he drove a variety of vehicles including petrol bowsers, the sanitation wagon, and Queen Mary trailer. He became the chauffeur for the senior armaments officer for 617 Squadron. He describes being prepared to be sent to Okinawa, but the war finished before he went. He was awarded a scholarship to study accountancy and successfully obtained his diploma. He then returned to Jamaica on HMT Empire Windrush.

Creator

Date

2020-08-07

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

00:53:51 Audio Recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AOtteyRA200807, POtteyRA2001, POtteyRA2002

Transcription

HH: Okay. Today is the 7th of August 2020. I’m Heather Hughes for the International Bomber Command Centre Digital Archive and I’m in Boston to talk to Ralph Ottey, a veteran of Bomber Command. RAF Bomber Command. Ralph, thank you so much for agreeing to do this interview. it's very exciting to have met you. Can, for the purposes of this interview would, would it be possible to talk us, to talk a little bit about your early life in Little London, Jamaica and then we'll come on to talking about your experiences during the Second World War serving with RAF Bomber Command and then we'll talk a little bit as well afterwards about how you came to come back to Boston and how come you are still here.

RO: Yeah, yeah.

HH: Okay.

RO: That’s fine.

HH: So tell us about your early life in Boston.

RO: Yes, well —

HH: In Jamaica.

RA: I was, well christened Ralph Alfredo Ottey. Really after my grandfather who was Ralph James Ottey. That's how. I was born in the little village of Little London in Westmoreland, Jamaica. British West Indies. Yeah. On the 17th of February 1924. I went to an elementary school in Little London. A Wesleyan Methodist Church School. And my, I was brought up by my grandparents Ephraim and Sierra Williams who were both prominent members of the church. I did fairly well at school and all the prospects were for me to become a teacher. I had, you had to pass an examination in Jamaica at that time called the Third Year Examination and then you can then apply to go to get a place at Mico College. The only training school for teachers, male teachers in Jamaica at that time. It is now a university.

HH: Is that in Kingston?

RA: That is. That is in Kingston. Which is a hundred and fifty miles away from. At that time it would be like fifteen million miles away from Little London to King, to Kingston. However, due certain circumstances at sixteen and a half I left the school. I passed my, what you call the third year Jamaican exam which gave me the right to apply for a place at Mico. But you couldn't get into Mico until you were nineteen. So I had two and a half years to read up. But then I was a, I was a pupil teacher being paid by the school thirteen shillings and four pence per week [laughs] That was. That was my pay that. Yeah. However, I left. I left there because I went to go to work for my uncle who had a bakery in Savanna-la-Mar. Savanna-la-Mar is the capital town of the parish of Westmoreland and my family is a very, quite dutiful family in, in Savanna-la-Mar. The first mayor of Savanna-la-Mar was an Ottey. Uncle Guy Ottey. So I was well, so I went to work for my Uncle Guy and I worked for, that was 19’ nearly the end of 1940. I was just over sixteen years old and, and I stayed with him for two years. But I always — they, they always want me to be this teacher but at the back of my mind what I wanted was to be a air gunner in an aeroplane. To shoot the Germans down. That’s, that’s all I wanted.

HH: Why?

RA: Well, because of Churchill. I used to know all of Churchill’s speeches. I, oh I managed the war with Churchill. I was disappointed when he didn’t consult me about these things that I had [laughs] And that was my thing in life. They were planning for me to become a teacher and so on. What I wanted was to be in the war. To be flying in an aeroplane shooting down Germans who were bombing London, you see. That was my life.

HH: It's, it's so interesting that you wanted to fly and in a, in an aircraft —

RA: Yeah.

HH: Shooting down Germans rather than, for example being at sea or in the army. Was there something very specific about the RAF?

RA: Special. The RAF was my thing because my father used to say to me, ‘Now, if you want to help in the war why don't you join the Jamaica Military Artillery?’ He said, ‘You have big guns and you're not even seeing the enemy. That's what you should be doing. Why you want to — ’ And I just treat it as a joke because the old man’s idea to be behind this machine gun shooting down Germans. Especially 1940 when the Battle of Britain, you see. That's what I, that was my motive. So I stayed with, I stayed with my uncle for two years. 1942. Then my father who was working with ESSO because the Americans had acquired a right to build bases in Jamaica and they were building a base near Kingston and my father was working for this big oil company and he got me a job with the base. The Jamaica base contractors. That lasted for about six, seven months when they finished building the runways so they laid off people and so and so . I went back to, to Little London because where the base was built was a hundred miles from Little London. So I went back to my grandparents in Little London in 19,’ at the beginning of 1943 and I got a job as a clerk in the local covered market. I used to go around and give people tickets and collect up money. And I, but my thing was the RAF, you see. It never never far away from me. Then suddenly, you know, yes they had a Census. 19’. A National Census in Jamaica in 1943. And I became a census enumerator so some of those stories about Little London I gained by going around doing the Census. So I know all the villages and the people in the villages and so and so. So I did. I did that and then I got, in 1943 [pause] yeah, that's right. I finished up 1943 then I went back to [pause] back to my uncle in Savanna-la-Mar. And I wasn't there very long when there was a notice in the [pause] the, the RAF was recruiting. That was interesting so I applied. I went. Took the exam. Didn't hear anything. Didn't, didn't hear anything from them for months. Then suddenly they said, ‘Come and sit the exam.’ So I went and sat the exams. Then like everything I didn't hear anything from them for a long time. Then suddenly they said, ‘Oh, well we're ready for you now. You have to come and take — ’ I passed the exam because I had to take a proper exam to get in the RAF. Did you know, not just for flying. You had to —

HH: Yeah.

RO: You took the RAF test, you see. So when, when this call came I went took the exam yes let's, got, got through that. And suddenly they say, ‘Oh, yes we want you.’ So we, I it went to another base in Jamaica which was a naval base at Port Royal which was a RAF camp on that base at that time. And I took the physical. Got through. Got through that all right and was given the RAF number, so and I I, they ask you, ‘What would you like to do?’ You know. So, of course, I said, ‘Oh, I want to be [pause] to shoot Germans down.’ Well, they say, ‘Oh, well you know,’ they said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you something. They said, ‘Your English is quite good so we'll put you down to be called a wireless operator/air gunner.’ Just the job as I thought. So I was signed up in the RAF to be trained as a wireless operator/air gunner and waited for a few months. Then they said, ‘Oh yes. We're ready for you now to go to England.’ So we, in the middle of the night they wake us up, put us on a boat and we went to a camp called Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia. American camp. The first time in my life I ever had anything to do with segregation because on this camp, a massive camp at a place called [pause] Oh God I forget the name of it. A camp. Camp Patrick Henry after the great American. Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia. And we stayed here for a few, a few weeks. And then suddenly we were based. We went on the biggest convoy. We went up to New York to catch a ship there and we went up [pause] I think we went on a ship that finished up. The Esperance Bay. Something like that they called it. We finish up being on this boat on the first convoy to come back to come to arrive in England during the, the invasion of France. While we were at sea the invasion took place. And this a massive convoy. Every day you're crossing the North Atlantic. Every day you are at the same place just surrounded by ships and you have their practicing shooting. And I I was very interested in the guns. Firing and so on. But one of the interesting things was, oh when you're young you do not, you're not bright enough to um to sense danger. We were at the bottom of the ship you see and at night they used to lock us in because we were untrained, you see. And if there was any possibility of people getting off, the people who were trained were [pause ] but we, we didn't, didn't worry one bit. Yeah. I think all that would happen to somebody else it wouldn’t happen to me. So it did. It didn’t happen. Never happened to us. We arrived at Liverpool and the first happy thing that really happened was that we were the only, we were the ship where the British servicemen were on [pause] most of them was Americans you see. These massive convoys. So they made the way to the port of Liverpool for British servicemen took off. So we were the first ship to dock at Liverpool.

HH: Great.

RA: That, and when we got there we were met by a Jamaican admiral. Admiral Sir Arthur Bromley, I always remember he was born as an Englishman born in Trinidad and he came, and I and remember the first thing he said to us, he said, ‘Is George Hadley with you?’ Because George Hadley was a great cricketer. I’ll always remember that. Oh, ‘Is George Hadley with you?’ But George Hadley was elsewhere. So we got off the ship and we're not supposed to know where we were going you see. But somehow the grapevine said you're going to Yorkshire. Right. So there was no we went through these stations and so on. There's no names on the stations. That kind of thing. So we finish up at a place called Filey, in Yorkshire. RAF training school. So we went to Filey and we spent thirteen, thirteen weeks being trained there. Doing the military training thirteen weeks.

HH: Were most of the people at Filey from um the Caribbean? Were there other people as well at Filey?

RA: Oh yes. Oh yes. There were lots of Jamaicans who and, and from other places. British Guyana there.

HH: Okay.

RA: And Trinidad. And we were West Indians. Yeah. And so we went to, we went to Filey and we were in, had another interview all over again. And this, I sat down with various officers so now, ‘I see you, you, you want to, you’re down here to be, you’re gunner and wireless operator.’ I say, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Well, unfortunately the way the war is going we don't, we don't have that kind of job anymore. You're either you're either an air gunner or you're a wireless operator. But we have plenty of, we have plenty of those. But what, seeing as your English is,’ that’s what I said to him. He said, ‘Seeing that your English is quite good I think they way you can serve best is you could be a motor transport driver.’ So you know that was it. Well, I’m in the service.

HH: Were you disappointed?

RA: I had to do what — eh? What?

HH: Were you disappointed?

RA: Oh course. Very disappointed. I mean.

HH: But it probably, it probably meant that you would survive the war.

Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. I I wanted to be in the thick of, in the thick of it so [pause] but of course then I took the oath so there I couldn’t say to this officer, ‘I’m not going to do that.’ He said, ‘That's what you, what you serve. You'll be good at that. So you will be good at, you’ll be good at this. We, we, we need people who, with good English.’ So they were, we did thirteen weeks.

HH: At Filey.

RA: At Filey. And on the passing out one of the people who, West Indian notables who came you know how later on. Yes. I was, because I didn’t keep my mouth shut I was part of the guard of honour. And how this thing happened was this, this sergeant who was training us saying to us that, ‘We are going to have, in the passing out there will be Colonel's Oliver Stanley who is your Colonial Secretary will be coming.’ And I said to him, ‘Well, corporal he isn't our Colonial Secretary. He is the Colonial Secretary.’ ‘Ah.’ So he said, oh he called me mister, he said, ‘Oh. Oh, Mr Ottey,’ he said, ‘Oh, since that you're so you're right but seeing that you're so bloody clever you will be on the guard of honour.’ Which meant a lot of extra training to be, so I realised that , to keep your mouth shut up.

HH: Yeah.

RA: So I was on the guard of honour to meet Colonel Oliver Stanley, the Colonial Secretary. And they were suddenly in the line Louis Constantine was one of the West Indian notables Again, I don't know why to me. He came and spoke to me. He came and spoke to me. He asked me where I was from. Jamaica sir He said, ‘Who brought you up?’ You know. Who? Your family. I said, ‘I was brought up by my grandparents in a little place called Little London.’ And so he said to me, he says, ‘You'll be spending a lot of time in England. He said, 'The English people are very fair,’ he says, ‘And I’m telling you this as one who have taken a hotel who put a colour bar on me because they had Americans there. And I’m telling you that if you, if you behave in England as you behave in the village where you come from, where your uncles and aunties are there you'll be quite alright in England,’ he said, ‘Because,’ he said, ‘English people are fair.’ He said, ‘Whatever happened they are fair-minded so you just do that. Just behave as if you're in the village and your uncle and grandfather also are there.’

HH: And did you? Was that your experience? Is that? Did — was that your experience?

RO: Yes. You see that, that's what he, that's what he, he said to me and so I always remember, I remember that that that I should don't get excited about what's going on. ‘Just behave as you would in Little London.’ He said, ‘Respect elders,’ because you had to in Little London. Respect elders and and so on. So you're a part of it. So that's what, that's what I did and as, as great fortune will fall on somebody I came down to the village from Filey into the town. It was a holiday place and I was in a café, in a little cafe and a little girl [pause] she was about, she was nine years old at the time came up to me and said, would, have I any foreign stamps? She said, she said she was a philatelist or something. This big word and I didn't know what it was really. She was a stamp collector. And had I any foreign stamps? You see. So I said, ‘Well, I haven't. I've got some at the camp because I have letters waiting for me.’ When I get on with the other boys. I said, ‘Well I haven't got any handy but I have some at the camp and I have people in my billet who have at the same. So I will get them for you. When are you going?’ I said. ‘Oh, we are here for a fortnight,’ she said. ‘Anytime you come,’ So I said, ‘Well, next time I'll be able to come out would be — ‘’ at such and such a time and we'll meet. So she took me over to meet her parents. Arthur [pause] Arthur and Lillian Pearce from Scunthorpe. Right. So I met them and I brought the stamps and we had a chat and they invited me to have a cup of tea with them and so on. Then just before, just before she says, ‘Have you,’ Aunt Lil said, ‘Have you, have you any family in England?’ I said, ‘Oh no.’ She said, ‘Well, we’re making you an offer, she says. Why don't you have us as your family and you cannot always come at 157 Cliff Garden, Scunthorpe to spend your holidays.

HH: Lovely.

RA: So from there we get Uncle Arthur and Aunt Lil and this little girl Pat. They called me family. That's where, when I got married they acted as my parents and we —

HH: Did you get married near Scunthorpe?

RA: I got married in Scunthorpe but that's a a later story.

HH: Yeah.

RA: And I I of course I left Filey. Passed out. I didn’t, I expected that I would do, do well at shooting because I loved it but I didn't do as well as I, that I thought I'd get a prize but I didn’t. I was disappointed because I thought I did fairly well but there were chaps who were better. Much better than me. So I left. I left Filey. Yes. I did. I put a story in I didn’t tell you. I missed that, that. They had an exhibition. A West Indian, a West Indian painting exhibition in Sheffield and there again I was part of the guard of honour.

HH: So you got to go to Sheffield.

RA: I went to Sheffield. Marched through the town to the, this Cutlery Hall where we met the Lord Mayor and had, and had something called Yorkshire pudding. Which was a bit disappointing because I was waiting to have a pudding. I was ready to have a pudding and it didn’t turn up. This was a little thing that was [laughs] But anyway we marched through the city and met the Lord Mayor and so on. Went to this exhibition thing. Then I got posted to a place called Little Rissington in Gloucestershire.

HH: Now, in your, in your in your memoir, “Stranger Boy,” you talk about how a corporal accompanied you to Little Rissington.

RA: Yes.

HH: Why was that? Because normally when you were posted somewhere else you were just told to get there on, on your own. But you were accompanied by a corporal.

RA: We, I was taken to um, to this place by, but it was, it was the usual RAF thing, or service thing. He lived around that place. So it was a perk for him to escort us. So he was —

HH: Okay.

RA: He got the chance to get home.

HH: Okay.

RA: I know that now. I didn't realize that but he he took us. There was a party of us you see. About six or seven who was sent to Little Rissington, and I spent my time at Little Rissington. Then I went to Blackpool and Blackpool was an exper, was an experience there. Yeah. n So I got I got involved with American colour prejudice for one incident there and I was rescued. I think I was rescued by a Scotsman who, there was about three Americans to me. I was with a girl. I was. I used to meet her. Me and another English chap used to meet this girl and we used to, we were only friends. We used to go to the amusement places and so on but this time this English chap wasn't, wasn't there and these Americans decided that they were going to beat me up you see. And there was this English serviceman who saw what was happening and intervened and said, you know ‘I can't see what your, your own ways but if you're going to get at him you're going to get through me first,’ you know. Like so they backed off. But that was a thing, you see. Yeah.

HH: Yeah.

RA: But so I, but I learned something in, in Blackpool. I went, I used to, when we get plenty of, we were billeted you see. we didn’t have camp I used to go in town and I went into a jewellery shop. And this chap was very keen to find out about me you see. Then he said to me, he said that he was Jewish, you see. I’m Jewish.’ And so on. So I said to him, ‘Why is it that people are against Jews? So, he says, ‘It’s a long story.’ I said, ‘In Jamaica Jews are just white rich people and that's all really. They're white. They're rich. That's it.’ And, and he said to me, ‘Well it's a long story,’ he says, ‘It started from ancient times when Christians weren't supposed to be usurers. And most of the people with money and the king's and so on used to have a Jew who he used to borrow money and so on. So he says, ‘We Jews, we built up a, between his good states with the Jews between each other and so we, we got in the business of usury because that Christians would, yeah. And he said, he said that's what the cause of it that that there’s antipathy about Jews really.’ We get into a position where we have handling money.

HH: Yeah.

RA: Yeah. But I mean I didn't know. I didn't know that.

HH: Interesting.

RA: I didn't know about that. So I learned. I learned something. I learned something there.

HH: You did.

RA: After, I I passed out as a driver — they did thirteen weeks, you know.

HH: That was at Blackpool.

RA: No. No. No. Blackpool. I only spent a few weeks at Blackpool.

HH: Okay.

RA: Then they transferred us to number one RAF Transport School down in Wiltshire. Melksham in Wiltshire. And we, I spent thirteen weeks there and I passed out as a AC1 in driving. And I did. I could drive. Name it I could, I could drive it, you see. So I was alright. Then I was transferred. No. I became [pause] I was on my own then. They just, I got my pack and my tickets to turn, to come to RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire. There's nobody taking me there. I had to work myself from from Wiltshire to London to get to that's when I could have done with the help to get on there to go to a place called East —

HH: Kirkby.

RO: East Kirby. It was the nearest, the nearest [pause] No I didn't go to — no to go to Boston. I had to go to. Coningsby. That's right. I got, and I got as far as, I got to London alright and crossed station. Got on the train. Got to Peterborough. Get me get my connection to Boston. I got to, I got to Boston and nearly got into a fight. I got off the train and there wasn't any [pause] there wasn't any any, any trains there. You had to wait for a transport from the camps to take us. So I was in with an older, more experienced airman and he said, ‘Oh well, we’ll go in that pub there and wait ‘til the transport come from the camp at Coningsby.’ So we got in there. As soon as I went in — trouble. There was a chap [pause] spoke to me in Spanish, you see. And I, I said to him in Spanish, the little Spanish I know whatever I said intended I’m a black man. And he got me by the throat. Not being allowed to move. I couldn't understand why. Where? How I said it meant that I, ‘I don't talk to you.’ Which was, all I was trying to tell him that I understand Spanish but I can't have a conver, I wasn't good enough to converse with him, you see. Yeah. But he was, he was going to beat, beat me.

HH: You, were you rescued?

RA: Oh yes. There was another airman there. ‘What do you think you’re doing?’ And that calmed him down. As usual with the RAF I got on the wrong bus. Instead of getting on the bus to Coningsby I got on the bus to East Kirkby. So I got to East Kirkby and they said, ‘You don't belong here mate.’ I can’t do, ‘But It's too late now,’ They fixed me up with a bed and next day they put me on a train and I got to Coningsby. Got to Coningsby. They say, ‘Oh we don’t want you here. You’ve got to go to RAF Tattershall Thorpe which is next door.’ So off I went. Booked in. And so I got through. There's a system where you have to book into the medical. When I finished that I found myself, and acquired a bike because it was a highly dispersed camp so you had to have a bike. So I had a bike. I went to the MT Section to report to the MT Section. And there was a Jamaican there who was at the camp before me and he, he tipped me off. He says, ‘You are the last one who come here so what's going, going to happen? He's going to give you the dirtiest job in, in the section.’ But he said, ‘You want to accept it as if it's a gold mine.’ You say, ‘Yes sergeant.’ You know, ‘Quite all right. No, no problem,’ you know. Truly a [unclear] So the first job I got in the RAF after doing six months of training was to drive the sanitary waggon. So, ‘Yes sergeant. That's quite all right with me.’ You know. So I i I did that for about four weeks. ‘Quite alright.’ Followed what my Jamaican friend tell me to do. Then Sergeant Colwaine said, ‘Hey, I have a job for you.’ Right. ‘Yes sergeant.’ He said, ‘You're going to be the Chauffeur for the senior armament officer.’ It’s a gold mine. So I got this job to drive the senior armament officer in 617 Squadron. I was attached. I didn’t know about 617 Squadron then.

HH: When did you? When did you become aware of 617 Squadron’s fame?

RA: It’s when I, when I start working with the squadron. So I became the driver for the senior, the senior armament officer, 617 Squadron.

HH: That's quite a job.

RA: Quite. Well, I thought I was on my feet. Not only that. Because it was a lot of what you call down time I realized that in the air force if you use your [pause] you can get training. So I, I signed up at the college to do book-keeping and accounts because I had a lot of waiting time. I just drive the officer there and wait on him and in that time I’m reading and writing up my answers and so on. So I spent quite a bit of time doing learning about bookkeeping and accountancy while I was driving the, the officer around. Driving all over the place. And then of course I get to know about the aircraft.

HH: Did you ever encounter any of the air crew?

RA: Oh yes. Of course, I met the aircrew. They were fantastic. And some of them was my age. You see I was just twenty. Well, some of them were just twenty. They were lads like me And so I got to know them and I got to go. To get inside the aircraft and know all about.

HH: Did you ever get to fly?

RO: I oh I went on a flight. They encourage you. They encourage you at that time if there's a possibility where they're doing an exercise and if there's a pilot you get a flight, you signed up, so I did. And my why flight was they were going to [pause] they they're doing about they had done the bomb, the raid on the dams already before that. But they used to fly up around Yorkshire, you know. They have some lakes. And they used to. And I went on a flight. But they encourage you. They encourage you to do that if you're ground crew and you're near. They encour, they used to encourage you to to, to get at it.

HH: To experience it.

RO: Yeah. But while I was with the, the squadron I learned a lot about the Royal Air Force because of association. I wrote a lot about it. I learned to respect the Royal Air Force. And the camaraderie, you know, being comrades, and in 617 we always used to you learned that the order of things in life was. There was god almighty. There was Winston Churchill. There was Bomber Harris of Bomber Command. There was Group 5. And 617 Squadron. That was how they drilled it in to you and that's how I lived. So while I was, and while I was attached to the squadron I I other than driving the the chief around, armament officer I did other jobs like, oh I could drive a Coles Crane. I did driving what they called a Queen Mary. Yeah. It's you know those big wings on a bomber. They have a workshop in Lincoln and you had to take them for any repairs to Lincoln. I was good handed I drove a bow, what you call a petrol bowser filling up aircraft. I also drove a [pause] equipment which is a, it's a boat and and a cart. Well, you see they had a bombing range. They had a bombing range.

HH: Close.

RA: Near Wainfleet. And this, this vehicle used to be able to take the targets out and if the tide catched up it became a boat and we've lost one or two where it got caught. Caught out there ready for the tide. Yeah. So I used to, I used to, used to drive that out to take the targets out to and so I had a very wide experience in driving all sorts of motor vehicles. Motor vehicles. Which if you follow my story it, when I finished, when I, you know I’m quoting. Yes. So I spent my time at Coningsby.

HH: [unclear]

RA: No at Tattershall Thorpe. And then when the war finished.

HH: Can I just ask you something about those bomber stations where you were based? Is that again reading your memoir on those years I got the impression that at most of the, of those stations there were quite a few black ground personnel. Was that correct?

RA: Yes.

HH: You know. You know.

RA: Oh yes.

HH: There were quite a lot everywhere.

RA: Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. Oh yes. Every station. Every station there was. Yeah. Oh yes but I I I don't know. I was fortunate in that I wasn't moved about. I, I was at Woodhall. What they called RAF Tattershall Thorpe. They call it Woodhall Spa but it was in the air forces as RAF Tattershall Thorpe. And then when, when the war in Europe finished I was still at RAF Tattershall Thorpe but the squadron was going to, 617 Squadron was going to move somewhere down south. I forget the name of the camp but we were going to go to Okinawa. Right. And I was sent on a course of Japanese aircraft rec.

HH: Oh gosh.

RA: At a place called Strubby in Lincolnshire. So I went. I went. I went on that course and while I was at that course they dropped the atom bomb and then I was scrubbed. And I was annoyed because I wanted to go to Okinawa. Fool. I mean, I don't say I should have known that I should have been glad if they’d posted me to the Orkneys not [laughs] Not Okinawa.

HH: And do you know the dropping of that the first bomb was seventy five years ago yesterday.

RA: Yeah.

HH: Yesterday was the 75th anniversary.

RA: Yes. I was, I was on a course then.

HH: And you were at RAF Strubby.

RA: Strubby. The Japanese aircraft rec.

HH: Incredible. Incredible.

RA: And I, and a incident there I’ll always remember. We, we were trying, using train to fire a twin mounted Browning gun. And we were all there learning and this youngster said to the sergeant, he said, ‘Hey sarge, now what [pause] if I shoot down the plane that pulled the target?’ And this sergeant, who was a comedian as well, he said, Son,’ he says, ‘If you follow the word of command when I give you the word of command to fire,’ because this plane was taking a drogue you see. ‘When I give you the word of command to fire if you hit that plane I will personally see that you become a air marshall.’[laughs] He said that. Because the drogues are apart, only a hundred yards behind the aircraft. So he said, ‘If you shoot that aeroplane down I’ll see you’re all right.’ So that’s what happened. The war, that part of the war finished for me at Strubby. And from then on it was. —

HH: It was winding down.

RA: Oh yes.

HH: The war effort. Yeah. Yeah.

RA: And I became, you know I of course kept on with my studies in. So in the end the the air force, the RAF and the Colonial Office give me a scholarship to do bookkeeping and accountancy. Business Management. So I got a scholarship to go to a college in, in [pause]

HH: Now, had you already, had before you got the scholarship had you already elected to go back to have your training and then go back to Jamaica?

RA: Oh yes.

HH: How many, how many people in your situation decided to stay rather than to go back?

RA: Quite, quite quite a few stayed because the option was open to me. The air force was keen to have people because at that stage we were trained people. So any, any Jamaican who wanted to stay in the RAF was welcomed with, with open arms you see because they trained people getting out into what you call Civvy Street and they you want people like myself who had three or four years in the service too. So I went to college. Did fair. Did fairly well at, at college. Got a diploma. Everything. And went back.

HH: But before you went back you had, you had met the love of your life.

RA: Oh, yes. Yes.

HH: By coming to Boston.

RA: Yes. Yes. Yes. I went to the Gliderdrome.

HH: So you need to tell us about playing cricket and dancing. That's the other part of the story you haven't mentioned yet.

RA: Yes. I got, I was, I got I I was quite I was quite a good cricketer from school. From school I was captain of the school, school team and so on. So I, I fitted very well with the the air force with sports you see. And I I did alright at the cricket in the RAF. In the RAF. And when I came to Boston I I I did. So, so yes I I went back to Jamaica of course. Went back on the Windrush.

HH: You did indeed.

RO: Came back on the Windrush and went to Trinidad and to Port of Spain in Trinidad and there's a, there's a main street in Trinidad. I forget the name of the street. And there's a main street in Kingston. And if you shut your eyes and taken, you could it could be the same place. The people. There were Chinese, Syrians, Indians in that street in Trinidad. Just like, just like Jamaica. So, the West Indians. There is something there's this thing that the same kind of people do thousands of miles away from Jamaica to Trinidad but they are, you know. It’s the same. You walk down the street and the same people. Indians, Chinese, Syrians, Jew, the same.

HH: Yeah.

RA: Some West Indians are really something. And of course we're British. That is a, that is a thing that [pause] I don't know if [pause] it's going from the story but I always see myself, you see as a coconut. You know about coconut. I am the, I am a coconut. I may be brown but inside I’m white because and the, the, the newer, the younger Jamaicans are not like that. They're not like me in that respect in that in growing up as I I wanted the things, the better things in life and the people who had the better things in life were the white people. They had the big house and the cars and the land and so on and that's what I, what I wanted. So deep down I was a, the joke about it was, ‘Oh, you're a coconut.’ But I say, ‘Yes. Yes, I am. I can't help, I can’t help it. I’m a child of my [age] Yes. I’m a coconut.’

HH: But I mean, you grew up when when that was part of the British world.

RA: Yeah, that’s right.

HH: Jamaica.

RA: When the young, the younger Jamaicans are completely different to —

HH: Yeah.

RA: To, to me.

HH: Yeah. They have just known independence.

RA: That's right I I have never voted in the Jamaica election.

HH: Yeah.

RA: You see.

HH: Yeah.

RA: I am, I am your typical Jamaican coconut [laughs]

HH: That's a wonderful story.

RA: Yeah.

HH: Ralph, I’m just going to [pause] So, Ralph we've got to the end of your story of service in the RAF and your return to Jamaica and we're going to conclude this part of the interview by saying it's part one and we will resume with part two and your life back in the UK in the, in the coming weeks.

RA: Okay.

HH: Thank you very much for talking.

RA: Yeah.

RO: Yeah, yeah.

HH: Okay.

RO: That’s fine.

HH: So tell us about your early life in Boston.

RO: Yes, well —

HH: In Jamaica.

RA: I was, well christened Ralph Alfredo Ottey. Really after my grandfather who was Ralph James Ottey. That's how. I was born in the little village of Little London in Westmoreland, Jamaica. British West Indies. Yeah. On the 17th of February 1924. I went to an elementary school in Little London. A Wesleyan Methodist Church School. And my, I was brought up by my grandparents Ephraim and Sierra Williams who were both prominent members of the church. I did fairly well at school and all the prospects were for me to become a teacher. I had, you had to pass an examination in Jamaica at that time called the Third Year Examination and then you can then apply to go to get a place at Mico College. The only training school for teachers, male teachers in Jamaica at that time. It is now a university.

HH: Is that in Kingston?

RA: That is. That is in Kingston. Which is a hundred and fifty miles away from. At that time it would be like fifteen million miles away from Little London to King, to Kingston. However, due certain circumstances at sixteen and a half I left the school. I passed my, what you call the third year Jamaican exam which gave me the right to apply for a place at Mico. But you couldn't get into Mico until you were nineteen. So I had two and a half years to read up. But then I was a, I was a pupil teacher being paid by the school thirteen shillings and four pence per week [laughs] That was. That was my pay that. Yeah. However, I left. I left there because I went to go to work for my uncle who had a bakery in Savanna-la-Mar. Savanna-la-Mar is the capital town of the parish of Westmoreland and my family is a very, quite dutiful family in, in Savanna-la-Mar. The first mayor of Savanna-la-Mar was an Ottey. Uncle Guy Ottey. So I was well, so I went to work for my Uncle Guy and I worked for, that was 19’ nearly the end of 1940. I was just over sixteen years old and, and I stayed with him for two years. But I always — they, they always want me to be this teacher but at the back of my mind what I wanted was to be a air gunner in an aeroplane. To shoot the Germans down. That’s, that’s all I wanted.

HH: Why?

RA: Well, because of Churchill. I used to know all of Churchill’s speeches. I, oh I managed the war with Churchill. I was disappointed when he didn’t consult me about these things that I had [laughs] And that was my thing in life. They were planning for me to become a teacher and so on. What I wanted was to be in the war. To be flying in an aeroplane shooting down Germans who were bombing London, you see. That was my life.

HH: It's, it's so interesting that you wanted to fly and in a, in an aircraft —

RA: Yeah.

HH: Shooting down Germans rather than, for example being at sea or in the army. Was there something very specific about the RAF?

RA: Special. The RAF was my thing because my father used to say to me, ‘Now, if you want to help in the war why don't you join the Jamaica Military Artillery?’ He said, ‘You have big guns and you're not even seeing the enemy. That's what you should be doing. Why you want to — ’ And I just treat it as a joke because the old man’s idea to be behind this machine gun shooting down Germans. Especially 1940 when the Battle of Britain, you see. That's what I, that was my motive. So I stayed with, I stayed with my uncle for two years. 1942. Then my father who was working with ESSO because the Americans had acquired a right to build bases in Jamaica and they were building a base near Kingston and my father was working for this big oil company and he got me a job with the base. The Jamaica base contractors. That lasted for about six, seven months when they finished building the runways so they laid off people and so and so . I went back to, to Little London because where the base was built was a hundred miles from Little London. So I went back to my grandparents in Little London in 19,’ at the beginning of 1943 and I got a job as a clerk in the local covered market. I used to go around and give people tickets and collect up money. And I, but my thing was the RAF, you see. It never never far away from me. Then suddenly, you know, yes they had a Census. 19’. A National Census in Jamaica in 1943. And I became a census enumerator so some of those stories about Little London I gained by going around doing the Census. So I know all the villages and the people in the villages and so and so. So I did. I did that and then I got, in 1943 [pause] yeah, that's right. I finished up 1943 then I went back to [pause] back to my uncle in Savanna-la-Mar. And I wasn't there very long when there was a notice in the [pause] the, the RAF was recruiting. That was interesting so I applied. I went. Took the exam. Didn't hear anything. Didn't, didn't hear anything from them for months. Then suddenly they said, ‘Come and sit the exam.’ So I went and sat the exams. Then like everything I didn't hear anything from them for a long time. Then suddenly they said, ‘Oh, well we're ready for you now. You have to come and take — ’ I passed the exam because I had to take a proper exam to get in the RAF. Did you know, not just for flying. You had to —

HH: Yeah.

RO: You took the RAF test, you see. So when, when this call came I went took the exam yes let's, got, got through that. And suddenly they say, ‘Oh, yes we want you.’ So we, I it went to another base in Jamaica which was a naval base at Port Royal which was a RAF camp on that base at that time. And I took the physical. Got through. Got through that all right and was given the RAF number, so and I I, they ask you, ‘What would you like to do?’ You know. So, of course, I said, ‘Oh, I want to be [pause] to shoot Germans down.’ Well, they say, ‘Oh, well you know,’ they said, ‘Well, I’ll tell you something. They said, ‘Your English is quite good so we'll put you down to be called a wireless operator/air gunner.’ Just the job as I thought. So I was signed up in the RAF to be trained as a wireless operator/air gunner and waited for a few months. Then they said, ‘Oh yes. We're ready for you now to go to England.’ So we, in the middle of the night they wake us up, put us on a boat and we went to a camp called Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia. American camp. The first time in my life I ever had anything to do with segregation because on this camp, a massive camp at a place called [pause] Oh God I forget the name of it. A camp. Camp Patrick Henry after the great American. Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia. And we stayed here for a few, a few weeks. And then suddenly we were based. We went on the biggest convoy. We went up to New York to catch a ship there and we went up [pause] I think we went on a ship that finished up. The Esperance Bay. Something like that they called it. We finish up being on this boat on the first convoy to come back to come to arrive in England during the, the invasion of France. While we were at sea the invasion took place. And this a massive convoy. Every day you're crossing the North Atlantic. Every day you are at the same place just surrounded by ships and you have their practicing shooting. And I I was very interested in the guns. Firing and so on. But one of the interesting things was, oh when you're young you do not, you're not bright enough to um to sense danger. We were at the bottom of the ship you see and at night they used to lock us in because we were untrained, you see. And if there was any possibility of people getting off, the people who were trained were [pause ] but we, we didn't, didn't worry one bit. Yeah. I think all that would happen to somebody else it wouldn’t happen to me. So it did. It didn’t happen. Never happened to us. We arrived at Liverpool and the first happy thing that really happened was that we were the only, we were the ship where the British servicemen were on [pause] most of them was Americans you see. These massive convoys. So they made the way to the port of Liverpool for British servicemen took off. So we were the first ship to dock at Liverpool.

HH: Great.

RA: That, and when we got there we were met by a Jamaican admiral. Admiral Sir Arthur Bromley, I always remember he was born as an Englishman born in Trinidad and he came, and I and remember the first thing he said to us, he said, ‘Is George Hadley with you?’ Because George Hadley was a great cricketer. I’ll always remember that. Oh, ‘Is George Hadley with you?’ But George Hadley was elsewhere. So we got off the ship and we're not supposed to know where we were going you see. But somehow the grapevine said you're going to Yorkshire. Right. So there was no we went through these stations and so on. There's no names on the stations. That kind of thing. So we finish up at a place called Filey, in Yorkshire. RAF training school. So we went to Filey and we spent thirteen, thirteen weeks being trained there. Doing the military training thirteen weeks.

HH: Were most of the people at Filey from um the Caribbean? Were there other people as well at Filey?

RA: Oh yes. Oh yes. There were lots of Jamaicans who and, and from other places. British Guyana there.

HH: Okay.

RA: And Trinidad. And we were West Indians. Yeah. And so we went to, we went to Filey and we were in, had another interview all over again. And this, I sat down with various officers so now, ‘I see you, you, you want to, you’re down here to be, you’re gunner and wireless operator.’ I say, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Well, unfortunately the way the war is going we don't, we don't have that kind of job anymore. You're either you're either an air gunner or you're a wireless operator. But we have plenty of, we have plenty of those. But what, seeing as your English is,’ that’s what I said to him. He said, ‘Seeing that your English is quite good I think they way you can serve best is you could be a motor transport driver.’ So you know that was it. Well, I’m in the service.

HH: Were you disappointed?

RA: I had to do what — eh? What?

HH: Were you disappointed?

RA: Oh course. Very disappointed. I mean.

HH: But it probably, it probably meant that you would survive the war.

Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. I I wanted to be in the thick of, in the thick of it so [pause] but of course then I took the oath so there I couldn’t say to this officer, ‘I’m not going to do that.’ He said, ‘That's what you, what you serve. You'll be good at that. So you will be good at, you’ll be good at this. We, we, we need people who, with good English.’ So they were, we did thirteen weeks.

HH: At Filey.

RA: At Filey. And on the passing out one of the people who, West Indian notables who came you know how later on. Yes. I was, because I didn’t keep my mouth shut I was part of the guard of honour. And how this thing happened was this, this sergeant who was training us saying to us that, ‘We are going to have, in the passing out there will be Colonel's Oliver Stanley who is your Colonial Secretary will be coming.’ And I said to him, ‘Well, corporal he isn't our Colonial Secretary. He is the Colonial Secretary.’ ‘Ah.’ So he said, oh he called me mister, he said, ‘Oh. Oh, Mr Ottey,’ he said, ‘Oh, since that you're so you're right but seeing that you're so bloody clever you will be on the guard of honour.’ Which meant a lot of extra training to be, so I realised that , to keep your mouth shut up.

HH: Yeah.

RA: So I was on the guard of honour to meet Colonel Oliver Stanley, the Colonial Secretary. And they were suddenly in the line Louis Constantine was one of the West Indian notables Again, I don't know why to me. He came and spoke to me. He came and spoke to me. He asked me where I was from. Jamaica sir He said, ‘Who brought you up?’ You know. Who? Your family. I said, ‘I was brought up by my grandparents in a little place called Little London.’ And so he said to me, he says, ‘You'll be spending a lot of time in England. He said, 'The English people are very fair,’ he says, ‘And I’m telling you this as one who have taken a hotel who put a colour bar on me because they had Americans there. And I’m telling you that if you, if you behave in England as you behave in the village where you come from, where your uncles and aunties are there you'll be quite alright in England,’ he said, ‘Because,’ he said, ‘English people are fair.’ He said, ‘Whatever happened they are fair-minded so you just do that. Just behave as if you're in the village and your uncle and grandfather also are there.’

HH: And did you? Was that your experience? Is that? Did — was that your experience?

RO: Yes. You see that, that's what he, that's what he, he said to me and so I always remember, I remember that that that I should don't get excited about what's going on. ‘Just behave as you would in Little London.’ He said, ‘Respect elders,’ because you had to in Little London. Respect elders and and so on. So you're a part of it. So that's what, that's what I did and as, as great fortune will fall on somebody I came down to the village from Filey into the town. It was a holiday place and I was in a café, in a little cafe and a little girl [pause] she was about, she was nine years old at the time came up to me and said, would, have I any foreign stamps? She said, she said she was a philatelist or something. This big word and I didn't know what it was really. She was a stamp collector. And had I any foreign stamps? You see. So I said, ‘Well, I haven't. I've got some at the camp because I have letters waiting for me.’ When I get on with the other boys. I said, ‘Well I haven't got any handy but I have some at the camp and I have people in my billet who have at the same. So I will get them for you. When are you going?’ I said. ‘Oh, we are here for a fortnight,’ she said. ‘Anytime you come,’ So I said, ‘Well, next time I'll be able to come out would be — ‘’ at such and such a time and we'll meet. So she took me over to meet her parents. Arthur [pause] Arthur and Lillian Pearce from Scunthorpe. Right. So I met them and I brought the stamps and we had a chat and they invited me to have a cup of tea with them and so on. Then just before, just before she says, ‘Have you,’ Aunt Lil said, ‘Have you, have you any family in England?’ I said, ‘Oh no.’ She said, ‘Well, we’re making you an offer, she says. Why don't you have us as your family and you cannot always come at 157 Cliff Garden, Scunthorpe to spend your holidays.

HH: Lovely.

RA: So from there we get Uncle Arthur and Aunt Lil and this little girl Pat. They called me family. That's where, when I got married they acted as my parents and we —

HH: Did you get married near Scunthorpe?

RA: I got married in Scunthorpe but that's a a later story.

HH: Yeah.

RA: And I I of course I left Filey. Passed out. I didn’t, I expected that I would do, do well at shooting because I loved it but I didn't do as well as I, that I thought I'd get a prize but I didn’t. I was disappointed because I thought I did fairly well but there were chaps who were better. Much better than me. So I left. I left Filey. Yes. I did. I put a story in I didn’t tell you. I missed that, that. They had an exhibition. A West Indian, a West Indian painting exhibition in Sheffield and there again I was part of the guard of honour.

HH: So you got to go to Sheffield.

RA: I went to Sheffield. Marched through the town to the, this Cutlery Hall where we met the Lord Mayor and had, and had something called Yorkshire pudding. Which was a bit disappointing because I was waiting to have a pudding. I was ready to have a pudding and it didn’t turn up. This was a little thing that was [laughs] But anyway we marched through the city and met the Lord Mayor and so on. Went to this exhibition thing. Then I got posted to a place called Little Rissington in Gloucestershire.

HH: Now, in your, in your in your memoir, “Stranger Boy,” you talk about how a corporal accompanied you to Little Rissington.

RA: Yes.

HH: Why was that? Because normally when you were posted somewhere else you were just told to get there on, on your own. But you were accompanied by a corporal.

RA: We, I was taken to um, to this place by, but it was, it was the usual RAF thing, or service thing. He lived around that place. So it was a perk for him to escort us. So he was —

HH: Okay.

RA: He got the chance to get home.

HH: Okay.

RA: I know that now. I didn't realize that but he he took us. There was a party of us you see. About six or seven who was sent to Little Rissington, and I spent my time at Little Rissington. Then I went to Blackpool and Blackpool was an exper, was an experience there. Yeah. n So I got I got involved with American colour prejudice for one incident there and I was rescued. I think I was rescued by a Scotsman who, there was about three Americans to me. I was with a girl. I was. I used to meet her. Me and another English chap used to meet this girl and we used to, we were only friends. We used to go to the amusement places and so on but this time this English chap wasn't, wasn't there and these Americans decided that they were going to beat me up you see. And there was this English serviceman who saw what was happening and intervened and said, you know ‘I can't see what your, your own ways but if you're going to get at him you're going to get through me first,’ you know. Like so they backed off. But that was a thing, you see. Yeah.

HH: Yeah.

RA: But so I, but I learned something in, in Blackpool. I went, I used to, when we get plenty of, we were billeted you see. we didn’t have camp I used to go in town and I went into a jewellery shop. And this chap was very keen to find out about me you see. Then he said to me, he said that he was Jewish, you see. I’m Jewish.’ And so on. So I said to him, ‘Why is it that people are against Jews? So, he says, ‘It’s a long story.’ I said, ‘In Jamaica Jews are just white rich people and that's all really. They're white. They're rich. That's it.’ And, and he said to me, ‘Well it's a long story,’ he says, ‘It started from ancient times when Christians weren't supposed to be usurers. And most of the people with money and the king's and so on used to have a Jew who he used to borrow money and so on. So he says, ‘We Jews, we built up a, between his good states with the Jews between each other and so we, we got in the business of usury because that Christians would, yeah. And he said, he said that's what the cause of it that that there’s antipathy about Jews really.’ We get into a position where we have handling money.

HH: Yeah.

RA: Yeah. But I mean I didn't know. I didn't know that.

HH: Interesting.

RA: I didn't know about that. So I learned. I learned something. I learned something there.

HH: You did.

RA: After, I I passed out as a driver — they did thirteen weeks, you know.

HH: That was at Blackpool.

RA: No. No. No. Blackpool. I only spent a few weeks at Blackpool.

HH: Okay.

RA: Then they transferred us to number one RAF Transport School down in Wiltshire. Melksham in Wiltshire. And we, I spent thirteen weeks there and I passed out as a AC1 in driving. And I did. I could drive. Name it I could, I could drive it, you see. So I was alright. Then I was transferred. No. I became [pause] I was on my own then. They just, I got my pack and my tickets to turn, to come to RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire. There's nobody taking me there. I had to work myself from from Wiltshire to London to get to that's when I could have done with the help to get on there to go to a place called East —

HH: Kirkby.

RO: East Kirby. It was the nearest, the nearest [pause] No I didn't go to — no to go to Boston. I had to go to. Coningsby. That's right. I got, and I got as far as, I got to London alright and crossed station. Got on the train. Got to Peterborough. Get me get my connection to Boston. I got to, I got to Boston and nearly got into a fight. I got off the train and there wasn't any [pause] there wasn't any any, any trains there. You had to wait for a transport from the camps to take us. So I was in with an older, more experienced airman and he said, ‘Oh well, we’ll go in that pub there and wait ‘til the transport come from the camp at Coningsby.’ So we got in there. As soon as I went in — trouble. There was a chap [pause] spoke to me in Spanish, you see. And I, I said to him in Spanish, the little Spanish I know whatever I said intended I’m a black man. And he got me by the throat. Not being allowed to move. I couldn't understand why. Where? How I said it meant that I, ‘I don't talk to you.’ Which was, all I was trying to tell him that I understand Spanish but I can't have a conver, I wasn't good enough to converse with him, you see. Yeah. But he was, he was going to beat, beat me.

HH: You, were you rescued?

RA: Oh yes. There was another airman there. ‘What do you think you’re doing?’ And that calmed him down. As usual with the RAF I got on the wrong bus. Instead of getting on the bus to Coningsby I got on the bus to East Kirkby. So I got to East Kirkby and they said, ‘You don't belong here mate.’ I can’t do, ‘But It's too late now,’ They fixed me up with a bed and next day they put me on a train and I got to Coningsby. Got to Coningsby. They say, ‘Oh we don’t want you here. You’ve got to go to RAF Tattershall Thorpe which is next door.’ So off I went. Booked in. And so I got through. There's a system where you have to book into the medical. When I finished that I found myself, and acquired a bike because it was a highly dispersed camp so you had to have a bike. So I had a bike. I went to the MT Section to report to the MT Section. And there was a Jamaican there who was at the camp before me and he, he tipped me off. He says, ‘You are the last one who come here so what's going, going to happen? He's going to give you the dirtiest job in, in the section.’ But he said, ‘You want to accept it as if it's a gold mine.’ You say, ‘Yes sergeant.’ You know, ‘Quite all right. No, no problem,’ you know. Truly a [unclear] So the first job I got in the RAF after doing six months of training was to drive the sanitary waggon. So, ‘Yes sergeant. That's quite all right with me.’ You know. So I i I did that for about four weeks. ‘Quite alright.’ Followed what my Jamaican friend tell me to do. Then Sergeant Colwaine said, ‘Hey, I have a job for you.’ Right. ‘Yes sergeant.’ He said, ‘You're going to be the Chauffeur for the senior armament officer.’ It’s a gold mine. So I got this job to drive the senior armament officer in 617 Squadron. I was attached. I didn’t know about 617 Squadron then.

HH: When did you? When did you become aware of 617 Squadron’s fame?

RA: It’s when I, when I start working with the squadron. So I became the driver for the senior, the senior armament officer, 617 Squadron.

HH: That's quite a job.

RA: Quite. Well, I thought I was on my feet. Not only that. Because it was a lot of what you call down time I realized that in the air force if you use your [pause] you can get training. So I, I signed up at the college to do book-keeping and accounts because I had a lot of waiting time. I just drive the officer there and wait on him and in that time I’m reading and writing up my answers and so on. So I spent quite a bit of time doing learning about bookkeeping and accountancy while I was driving the, the officer around. Driving all over the place. And then of course I get to know about the aircraft.

HH: Did you ever encounter any of the air crew?

RA: Oh yes. Of course, I met the aircrew. They were fantastic. And some of them was my age. You see I was just twenty. Well, some of them were just twenty. They were lads like me And so I got to know them and I got to go. To get inside the aircraft and know all about.

HH: Did you ever get to fly?

RO: I oh I went on a flight. They encourage you. They encourage you at that time if there's a possibility where they're doing an exercise and if there's a pilot you get a flight, you signed up, so I did. And my why flight was they were going to [pause] they they're doing about they had done the bomb, the raid on the dams already before that. But they used to fly up around Yorkshire, you know. They have some lakes. And they used to. And I went on a flight. But they encourage you. They encourage you to do that if you're ground crew and you're near. They encour, they used to encourage you to to, to get at it.

HH: To experience it.

RO: Yeah. But while I was with the, the squadron I learned a lot about the Royal Air Force because of association. I wrote a lot about it. I learned to respect the Royal Air Force. And the camaraderie, you know, being comrades, and in 617 we always used to you learned that the order of things in life was. There was god almighty. There was Winston Churchill. There was Bomber Harris of Bomber Command. There was Group 5. And 617 Squadron. That was how they drilled it in to you and that's how I lived. So while I was, and while I was attached to the squadron I I other than driving the the chief around, armament officer I did other jobs like, oh I could drive a Coles Crane. I did driving what they called a Queen Mary. Yeah. It's you know those big wings on a bomber. They have a workshop in Lincoln and you had to take them for any repairs to Lincoln. I was good handed I drove a bow, what you call a petrol bowser filling up aircraft. I also drove a [pause] equipment which is a, it's a boat and and a cart. Well, you see they had a bombing range. They had a bombing range.

HH: Close.

RA: Near Wainfleet. And this, this vehicle used to be able to take the targets out and if the tide catched up it became a boat and we've lost one or two where it got caught. Caught out there ready for the tide. Yeah. So I used to, I used to, used to drive that out to take the targets out to and so I had a very wide experience in driving all sorts of motor vehicles. Motor vehicles. Which if you follow my story it, when I finished, when I, you know I’m quoting. Yes. So I spent my time at Coningsby.

HH: [unclear]

RA: No at Tattershall Thorpe. And then when the war finished.

HH: Can I just ask you something about those bomber stations where you were based? Is that again reading your memoir on those years I got the impression that at most of the, of those stations there were quite a few black ground personnel. Was that correct?

RA: Yes.

HH: You know. You know.

RA: Oh yes.

HH: There were quite a lot everywhere.

RA: Yeah. Yeah. Oh yes. Oh yes. Every station. Every station there was. Yeah. Oh yes but I I I don't know. I was fortunate in that I wasn't moved about. I, I was at Woodhall. What they called RAF Tattershall Thorpe. They call it Woodhall Spa but it was in the air forces as RAF Tattershall Thorpe. And then when, when the war in Europe finished I was still at RAF Tattershall Thorpe but the squadron was going to, 617 Squadron was going to move somewhere down south. I forget the name of the camp but we were going to go to Okinawa. Right. And I was sent on a course of Japanese aircraft rec.

HH: Oh gosh.

RA: At a place called Strubby in Lincolnshire. So I went. I went. I went on that course and while I was at that course they dropped the atom bomb and then I was scrubbed. And I was annoyed because I wanted to go to Okinawa. Fool. I mean, I don't say I should have known that I should have been glad if they’d posted me to the Orkneys not [laughs] Not Okinawa.

HH: And do you know the dropping of that the first bomb was seventy five years ago yesterday.

RA: Yeah.

HH: Yesterday was the 75th anniversary.

RA: Yes. I was, I was on a course then.

HH: And you were at RAF Strubby.

RA: Strubby. The Japanese aircraft rec.

HH: Incredible. Incredible.

RA: And I, and a incident there I’ll always remember. We, we were trying, using train to fire a twin mounted Browning gun. And we were all there learning and this youngster said to the sergeant, he said, ‘Hey sarge, now what [pause] if I shoot down the plane that pulled the target?’ And this sergeant, who was a comedian as well, he said, Son,’ he says, ‘If you follow the word of command when I give you the word of command to fire,’ because this plane was taking a drogue you see. ‘When I give you the word of command to fire if you hit that plane I will personally see that you become a air marshall.’[laughs] He said that. Because the drogues are apart, only a hundred yards behind the aircraft. So he said, ‘If you shoot that aeroplane down I’ll see you’re all right.’ So that’s what happened. The war, that part of the war finished for me at Strubby. And from then on it was. —

HH: It was winding down.

RA: Oh yes.

HH: The war effort. Yeah. Yeah.

RA: And I became, you know I of course kept on with my studies in. So in the end the the air force, the RAF and the Colonial Office give me a scholarship to do bookkeeping and accountancy. Business Management. So I got a scholarship to go to a college in, in [pause]

HH: Now, had you already, had before you got the scholarship had you already elected to go back to have your training and then go back to Jamaica?

RA: Oh yes.

HH: How many, how many people in your situation decided to stay rather than to go back?

RA: Quite, quite quite a few stayed because the option was open to me. The air force was keen to have people because at that stage we were trained people. So any, any Jamaican who wanted to stay in the RAF was welcomed with, with open arms you see because they trained people getting out into what you call Civvy Street and they you want people like myself who had three or four years in the service too. So I went to college. Did fair. Did fairly well at, at college. Got a diploma. Everything. And went back.

HH: But before you went back you had, you had met the love of your life.

RA: Oh, yes. Yes.

HH: By coming to Boston.

RA: Yes. Yes. Yes. I went to the Gliderdrome.

HH: So you need to tell us about playing cricket and dancing. That's the other part of the story you haven't mentioned yet.

RA: Yes. I got, I was, I got I I was quite I was quite a good cricketer from school. From school I was captain of the school, school team and so on. So I, I fitted very well with the the air force with sports you see. And I I did alright at the cricket in the RAF. In the RAF. And when I came to Boston I I I did. So, so yes I I went back to Jamaica of course. Went back on the Windrush.

HH: You did indeed.

RO: Came back on the Windrush and went to Trinidad and to Port of Spain in Trinidad and there's a, there's a main street in Trinidad. I forget the name of the street. And there's a main street in Kingston. And if you shut your eyes and taken, you could it could be the same place. The people. There were Chinese, Syrians, Indians in that street in Trinidad. Just like, just like Jamaica. So, the West Indians. There is something there's this thing that the same kind of people do thousands of miles away from Jamaica to Trinidad but they are, you know. It’s the same. You walk down the street and the same people. Indians, Chinese, Syrians, Jew, the same.

HH: Yeah.

RA: Some West Indians are really something. And of course we're British. That is a, that is a thing that [pause] I don't know if [pause] it's going from the story but I always see myself, you see as a coconut. You know about coconut. I am the, I am a coconut. I may be brown but inside I’m white because and the, the, the newer, the younger Jamaicans are not like that. They're not like me in that respect in that in growing up as I I wanted the things, the better things in life and the people who had the better things in life were the white people. They had the big house and the cars and the land and so on and that's what I, what I wanted. So deep down I was a, the joke about it was, ‘Oh, you're a coconut.’ But I say, ‘Yes. Yes, I am. I can't help, I can’t help it. I’m a child of my [age] Yes. I’m a coconut.’

HH: But I mean, you grew up when when that was part of the British world.

RA: Yeah, that’s right.

HH: Jamaica.

RA: When the young, the younger Jamaicans are completely different to —

HH: Yeah.

RA: To, to me.

HH: Yeah. They have just known independence.

RA: That's right I I have never voted in the Jamaica election.

HH: Yeah.

RA: You see.

HH: Yeah.

RA: I am, I am your typical Jamaican coconut [laughs]

HH: That's a wonderful story.

RA: Yeah.

HH: Ralph, I’m just going to [pause] So, Ralph we've got to the end of your story of service in the RAF and your return to Jamaica and we're going to conclude this part of the interview by saying it's part one and we will resume with part two and your life back in the UK in the, in the coming weeks.

RA: Okay.

HH: Thank you very much for talking.

RA: Yeah.

Collection

Citation

Heather Hughes, “Interview with Ralph Alfrado Ottey. One,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 27, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/27255.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.