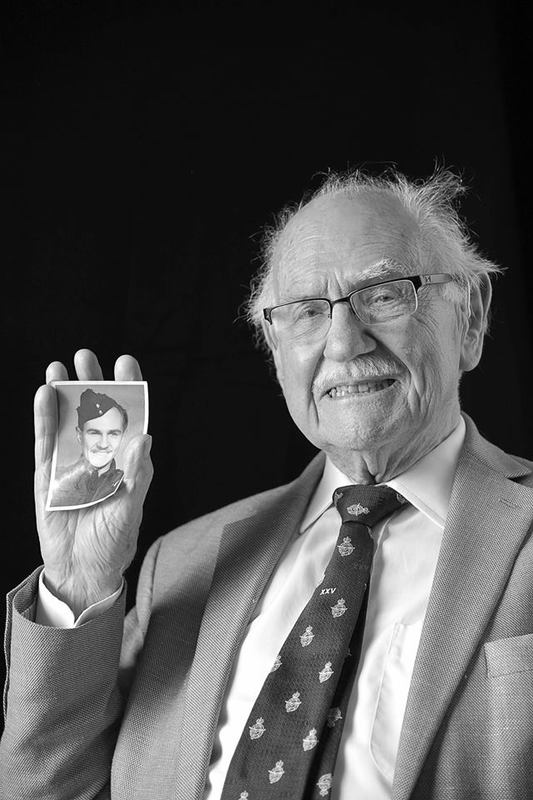

Interview with Reg Woolgar

Title

Interview with Reg Woolgar

Description

Reg Woolgar was born in Hove. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force in December 1939 and trained as a wireless operator/air gunner. He flew Hampdens with 49 Squadron. His aircraft was damaged by anti-aircraft fire on a mine laying operation to Oslo Fjord, including a bullet that passed through his gun sight. He recounts ditching a Hampden in the English Channel and being picked up by the Royal Navy off the Isle of Wight. He describes evenings out in Lincoln at the Saracen’s Head. After his first tour he was commissioned and became gunnery leader with 192 Squadron in 100 Group. Reg Woolgar was posted overseas in 1945 and recounts a bomb exploding near the King David Hotel, in Jerusalem. He also recounts tales of his time in Kenya and provides details of his career outside the Royal Air Force, as a planner and valuer for the city of London. He retired in 1971.

Creator

Date

2016-06-14

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

02:00:47 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AWoolgarRLA160614

Transcription

DE: Start the, start the interview.

RJW: On our seventieth wedding anniversary my grandson stood up and said Papa, Reg, Jimmy because they had all three, all three generations there. Sorry. Sorry.

DE: Ok. So this is an interview with Reg Jimmy Woolgar at the International Bomber Command Centre in Riseholme Lincoln. It’s for the IBCC Digital Archive. My name is Dan Ellin. It is the 14th of June 2016. Reg. Jimmy. Just for the start of this tape could you tell me about your early life and your childhood before you joined the RAF.

RJW: Well before I joined the RAF I left school in Hove and I joined the rates department as the junior clerk and it was really the office boy who made the tea but I became a valuations assistant in the valuation department there before the war and started to train as a surveyor and in 1939 on the 8th of December I went to the Queen’s Road Recruiting Office and I joined the RAF and there I was in a few days on my way to Uxbridge with about five or six other guys all from office appointments. When I joined I, like everybody else who wanted to join the RAF, I wanted to be a pilot. Well I actually went to the Queen’s Road office in September and they wrote to me and said, ‘We have an influx of pilot training but we can take you as air crew.’ I went to see them, asked what that meant. They said, ‘Well you will fly as a member of an air crew.’ I said, ‘Well can I ever become a pilot?’ ‘Oh yes,’ they said, ‘Once you’ve trained as air crew you can become a pilot.’ But of course it never happened because it just seemed to be that whenever I, wherever I went I eventually became an instructor and after being trained as instructor they didn’t really want me to be a pilot or anything else so I concentrated on doing wireless operating/air gunnery. That really is what happened to me before the war. Is there anything else you’d like to know?

DE: Well, yeah. What was, what was training like?

RJW: Pardon?

DE: What was training like?

RJW: Training. Ah. Well now we went to Uxbridge for the ab initio course, the square bashing. Famous words which you’ve used, heard before, you know the sergeant who comes in to the billet and says, ‘Anybody here play the piano?’ ‘Oh yes, I play the piano.’ ‘I play the piano.’ ‘Oh well you two go and move the piano from the officer’s mess to the sergeant’s mess.’ Having got all through all that, off we went. First of all we went to Mildenhall doing absolutely nothing because there was a bottleneck of getting to the wireless training school so we spent about three or four weeks at Mildenhall doing guard duty. Sometimes going in the cookhouse even and then we went to a station called North Coates Fitties on the east coast and we, we mainly did guard duty there. We were, it was a fighter squadron and we were sent out to guard the beacons around, around the runway, all that sort of thing. Waste of time but never mind. That took us until the early part of 1940 and then we were posted down to Yatesbury, wireless training course. I think that took, I can’t be absolutely certain, the dates are in my logbook but I think it must have taken us until about April, oh, yes, it took us ‘till about April and then we went to West Freugh on the east coast er west coast of Scotland for gunnery training and low and behold we all became sergeants. I can always remember the advice given to us by a warrant officer, the peacetime warrant officers and people of that ilk they did some, a little bit resent that air crew would automatically become sergeants but they did try to knock us into shape and I remember we had a cockney warrant, station warrant officer who tried to guide us on etiquette in the sergeant’s mess and he said, ‘Ah, er, you will be at liberty to invite ladies to a mess dance but make sure you invite ladies [emphasise] and not ladies.’ And he said, ‘Now you’ve got three stripes, the girls will be chasing you but just be careful who you pick if you marry them,’ and he gave jolly good advice, he said, ‘Take a good look at her mother because what she’s going to be like in twenty to thirty years’ time.’ Anyway, off we went. They sent us on leave and said that we would be, receive instructions for posting and we did. We, we, a new, another bottleneck for OTU so in the meantime we went to Andover. Now, Andover, I was there at the time of Dunkirk. I remember that because going into the local town, cinema and that sort of thing the local army chaps that were coming back from Dunkirk were a bit fed up with the RAF because they hadn’t seen any Spitfires so it wasn’t a very comfortable time but from there we went to OTU. Now that was number 10 OTU at Heyford, Upper Heyford. We had our first real flights. Started off in Ansons, staff pilot taking a delight in trying to do aerobatics in an Anson to see how many guys they could make sick but anyway [laughs] we, we were supposed to crew up but it was a bit of a haphazard thing. You found yourself in one crew one week and another crew the next week. I had my very first Jimmy escape there. Um, it had been snowing and we were grounded and then suddenly there was a break and we were sent off and I was sent off with a New Zealand pilot, Sandy somebody. I can’t remember, and he was a bit dodgy. Anyway, we took off and the cloud base came down, fog or, no, cloud base and I couldn’t get a peep out of the wireless set, I couldn’t get a DCM back to base so we stooged around for a bit and he said over the intercom, ‘Jimmy I’m going to land in a field.’ ‘Oh ok.’ I decided, I came out of the rear upper turret and I crawled back and I sat up behind him. He came down to a field, through a break heading for some trees I thought but he put his wheels down and of course it was a ploughed field underneath the snow. He came in very fast and we went, tipped right over, right over. At the very last moment apparently, I never remember doing this, I leaned over his shoulder and knocked his, the quick release of his harness and he flew out of the cockpit and down. He hit the ground, he broke a rib I think, and the aircraft went over and I shot back, right back to the back bulkhead and I had a bit of a head wound but it wasn’t very much and the aircraft was a right off. Right. It didn’t catch fire thank God. We were called away. When we had the inquest with the CO I got a right rollicking 'cause I couldn’t get through to base on the radio but I couldn’t get anything out of it but I even got a bigger one for releasing his harness and they said, ‘That was, you should never have done that but you saved his life.’ They said that, ‘Had you not done that he would have broken his, he would probably, he probably would have broken his neck or broken his back.’ So it was a good thing that it happened but it shouldn’t have done [laughs]. I had another, I was in another crash there where we ran up behind another aircraft and damaged it and injured the rear gunner but I was at the far end so I was ok. But this seemed to happen to me for some reason or other and I don’t know why, at the end of the course instead of going off on ops with a crew I was what they called screened. I was a screen operator instructor and I flew in Hampdens and Ansons with crews coming through. Just looking after them actually. Making sure that the wireless operators did what they should do or got through if they couldn’t and that sort of thing. I was there for oh far too long. I didn’t arrive on to the squadron, 49 Squadron, until the 1st of September 1941. My very first trip was to Berlin. The very experienced pilot, Pilot Officer Falconer, who was quite elderly, he was twenty six so we called him uncle [laughs]. He eventually, he became a wing commander, he commanded a squadron but he was killed unfortunately. Very nice guy. Anyway, after we went to Berlin and on that occasion it was quite a famous one. Head wind going out, head wind coming back. Ten tenths cloud and nil visibility coming in. Being given the order to go on to 090 and bail out so we got there and Uncle Falconer said to the crew, ‘We may have to bail out chaps.’ So then squeaky voiced me from the back said, ‘Oh skipper, I’ve pulled my chute.’ Actually I’d pulled it on the way out and I was more scared of having a DCO that is, Duty Not Carried Out, DNCO and being responsible for returning than actually taking my chance with the chute so I kept mum, I didn’t say anything. And when I told him I can’t actually repeat for the tape exactly what he said but it wasn’t very polite and I don’t blame him. In actual fact he found a break in the, in the overcast and he landed with wheels down in a field at a place called Withcall. Withcall near Louth and um, er, near Melton Mowbray. It was under some high tension cables and it was so tight they couldn’t fly the aircraft out. They took the wings off and put it on a loader to get it back. That was my first trip. Baptism of fire. Every trip, nearly every trip has an anecdote but the ones that stand out are, we went up to Inverness or somewhere. I can’t remember. It’s in the logbook. Inverness or somewhere like that to do a trip to Oslo Fjord laying mines, being told, ‘Chaps pick the right fjord because if you don’t you’ll come up against a blank face of rock and you won’t be able to turn around.’ Anyway, we did. It was almost daylight all the time. Up we went, down the fjord, laid our mine. Coming back, on the headland, as we passed across the headland em we were fired on. Some light tracer stuff came up. Very small. I said, I was at the rear of course as the wireless op. I said, ‘Oh, let’s go around and shoot them up because there’s other guys behind us.’ And the skipper said, ‘That’s a good idea.’ So we circled around, we came back and all hell let loose. They peppered us. We had thirty six holes on our starboard side wing, starboard fuselage mainplane but it didn’t affect the aircraft. I think the flak was a little bit dodgy but anyway came back all right. As I got out of the aircraft the ground crew came and they said, ‘Hey sarge,’ they said to me, ‘Have you seen your cockpit?’ I said, ‘No, what’s wrong?’ ‘It’s got bullet holes in it.’ ‘It’s got bullet holes in it?’ They said, ‘Yeah.’ And they said, ‘Look your flying suit’s all torn’. And there’s a bullet hole at the back of me and then you know after I’d been sent to recover [laughs]. They next came to me and said, ‘You’re never going to believe this.’ The upright of the gun sight on my VGO twin guns had a bullet hole through it like that. The armourer gave it to me. I had it for many, many, many years. Unfortunately, it was lost but it was, I was proud to be able to show a bullet came out [?] as I was looking through it [laughs] so you know why the name lucky Jim sticks doesn’t it?

DE: Yeah. Definitely yeah.

RJW: Well that was then. We were, er, we tasted one of the first delights of the master searchlight. They introduced a blue central searchlight beam, radar controlled I think and all the other beams came on it and we were over Hamburg and we caught that and we had a hell of a pasting with the flak but old Allsebrook was very good and he got us out of that. We had one or two other things but like everybody else did. You never got, you couldn’t get through trips without having some sort of trouble sort of thing.

DE: Sure, sure.

RJW: Anyway, my last, no, next to last trip of course was by ditching which I’ve written about. Would you like me to — ?

DE: If you could talk about that for the tape that would be wonderful as well. Yes please.

RJW: Oh yes.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: Well here goes. We took off about, I don’t know when it was. We were on Hampden G for George A397. We em, we were going to Mannheim. I think it was our twenty third trip and by this time we were a bit blasé. We thought going to be a piece of cake this. Mannheim. Yeah. That’s alright. So we weren’t really worried about it. The trip out was perfectly alright, over the target there was some flak but it wasn’t heavy flak, it wasn’t very much and we didn’t think that we’d caught any but just as we left the target our port engine cut dead and Ralph wasn’t able to do the relevant, it just stuck there. So we started to lose height. We lost height, we were somewhere about seventeen, eighteen thousand feet and we came down to four thousand eventually. In the process of doing that we got rid of all the heavy stuff we could think of. The guns. The bombsight. Unfortunately, Bob, the navigator, Bob Stanbridge stuck all his nav gear into parachute, one of the parachute bags that he used to take it out there, opened the doors in the navigator’s position, they swing inwards and to get rid of the bomb sight and the nav bag went out as well so we didn’t have any —. Anyway, off we went. Ralph was getting cramp in his leg holding the opposite rudder because of the loss of the port engine. Bob tried to tie the rudder pedal back with a scarf but couldn’t. Then I had a go. That was the scariest moment of all 'cause I had to unplug my intercom and had to crawl underneath in the dark but I did — I did actually manage to tie it up and that lasted for a while. I sent a plain language message out while we were still over France to say that we’d lost our port engine and may have to bail out, and although I was never a good wireless operator and I hated being a wireless operator, that message got through [laughs]. Anyway, eventually the fuel was down to zero and Ralph said, ‘Well, we’re over the sea, we’re going to ditch.’ So by this time of course we’d got all the hatches open because we’d been ready to bail out so all the sea came in. Anyway, he made — he made a good landing on top of the fog to begin with [laughs] but after that he made a jolly good landing and down we went. We scrambled out on to the wing, on to the port wing. The dinghy was supposed to burst out of the engine nacelle because of an immersion plug but of course it didn’t but Bob knew the procedure and with the heel of his flying boot he dug into the port engine nacelle and pulled the plug and up came the dinghy and started to inflate. It didn’t fully inflate but it started to inflate and by this time the four of us were standing on the, on the wing. All our ankles were awash in water. We then saw that the dinghy was attached by a cord disappearing into the engine nacelle and one of us said, ‘Well if the immersion plug didn’t work this won’t work, we’ll be pulled down,’ and Ralph said, I don’t know whether he said, ‘Just a minute chaps,’ but I think he might have done. He undid his flying jacket, went into his tunic pocket, pulled out a little tiny leather case out of which he took a pair of folding nail scissors, he then — he cut the cord, he did the scissors up, put them back in the case, back in to his pocket and he stepped into the dinghy with the rest of us. As we shoved off dear old G for George went down under the waves and there we were. We had to pump the dinghy up with the bellows because it wasn’t fully inflated but we managed alright. We were absolutely enhanced with the rations that were actually sealed in the bottom because there was a notice on it that said “Only to be opened in the presence of an officer” [laughs] so we said, ‘Well good for you Ralph.’ He was a pilot officer. And come daylight, in the far distance we did just spot what we thought were high tension pylons and some cliffs and we thought, well we were heading for Scampton of course, we thought oh well perhaps we’d drifted too far north, over-compensated and we were off Yorkshire, Whitby or somewhere like that. Anyway, not long after that that disappeared, we drifted around. We used the coloured dye, fluorescent dye in to the sea to identify ourselves and paddled and paddled around and eventually came back and found we were at the same spot again. The sun came out in the morning. It was very cold and very choppy. It was the 14th / 15th of February. It was cold. Anyway, we suddenly saw a school of porpoise and that was light relief until one of the crew said, ‘Yeah it’s all very well but what happens if one of these guys comes up underneath the dinghy?’ he said. Furious paddling away. We weren’t really gloomy, I don’t know why. I seem to think oh yeah, well we may get picked up but for no particular reason. We did see an aircraft which we thought was a Beaufighter in the distance but it didn’t see us. We sent the flares up but it didn’t do any good and then quite late in the afternoon we heard an aircraft engine and out came a Walrus. Circled round, waggled it’s wings, stayed with us, only a short time and off it went and it was almost two hours later when a motor anti-submarine boat pulled up and dragged us aboard. Eh, first question was, ‘Where are we?’ And somebody said, ‘We’re off St Catherine’s Point.’ ‘Oh, St Catherine’s Point. Where’s that?’ ‘The Isle of Wight.’ [laughs] And instead of being off Yorkshire we’d taken a huge curve and we’d been flying down the channel so luckily our fuel had run out when it did and we didn’t go too far out but the other thing was that the navy crew told us, ‘You’re dead lucky because you’re near a minefield. If you’d been in a minefield we wouldn’t have come out.’ So it was jolly good. We um, we survived all that, all three of us. Jack had frostbite. I remember cuddling his feet under my jacket actually ‘cause he was very cold. He got frostbite because he’d been sitting in the tin and he’d had the hatch open all the way but that was the only casualty that we had but it was quite a week because if I remember rightly at the beginning of the week we went to Essen, which was never much of a cup of tea that place, it was always pretty hot. And in the middle of the week we went on the Channel Dash. The Channel Dash was when the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau left Brest and that was quite curious because we’d been standing by for several days and we’d been given a sector. Our sector was off somewhere near Le Havre. If they ever got that far we were told that we would have to go out. On this particular morning after a while on standby we were stood down from the Channel Dash and the weather wasn’t very good but our bomb load was changed from armour piercing to GP bombs and we were sent off on a night flying test possibly for ops that night. We were recalled while we were actually in the air and sent off but not to Le Havre but off the coast of Holland because the ships had gone that far and been undetected and off we went. We didn’t see the ships but we saw, we think, an armed merchantman or something or other which was firing away but we didn’t really get near. The weather was so bad we really couldn’t see. What we did see, we saw a Wellington and we didn’t know that Wellingtons were on the trip but later we discovered that there was an armed, an unmarked Wellington which the Germans had captured and they were using it as an escort for the ships and it was coming in and some crews actually did encounter it firing you know. We only just saw it. We didn’t get through [?]. Anyway, it was uneventful for us in actual fact. I think we lost four crews out of the twelve that were sent up. I think I’m right about that but it’s in our journal. One more trip we did together as a crew and then later I’ll talk, I’ll talk about my rear gunner.

DE: Ok, yeah, yeah.

RJW: Our pilot, J F Allsebrook was posted away, the crew was split up. I think Bob Stanbridge was also posted but myself and Jack Wilkinson, Jack Wilkinson, he was the rear gunner we were left hanging around to be crewed up as wanted. Anyway, we started to crew up with Reg Worthy. A very competent pilot and we were very happy with that and in March we were crewed to go with him on ops. Unfortunately I had contracted sinusitis. Oh I remember. I’ll talk about that later, I’d contracted sinusitis and at times I got it very badly. It was very painful so I went up in the morning to sick call [?] — sick bay to try to get some inhalations to help me and they tested me and grounded me. They said, ‘You’re not flying like that. You won’t be able to hear anyway.’ [laughs] I protested a lot because I wanted to do the trip but no, no and when I broke the news to Jack he was extremely despondent. He didn’t want to go. He wanted to opt out. ‘I don’t want to go without you Jimmy because you’re lucky.’ I persuaded him that he’d be alright and, because I was replaced by McGrenery [?] who was a very competent WOP/AG who’d flown with me on a number of occasion and he was a hell of a nice guy. Sadly, the trip was to Essen and they were caught by an ace night fighter pilot called Reinhold Knacke on the way back, off the coast of Holland, just on the border and they were shot down. All killed. Reg Worthy and McGrenery were buried in Holland and Jack was washed up off the coast of Denmark. It’s quite amazing actually. And he’s buried in Stavanger. So there’s sad [?]. I had this sinus trouble. It was because much earlier on, on a trip to Brest we were in the target area and we lost oxygen and when you lose oxygen you dive down so we did a very steep dive very quickly and apparently my left frontal sinus became perforated. This bedevilled me a lot. In fact the problem was if you went through the medics with it too much you got yourself grounded and of course you lost your rank as a sergeant, you lost everything. So you didn’t sing too much about it. I remember that after the, after ops I was posted to a couple of training units. One at Wigsley. I’ve forgotten the name of the other just for the moment but it’s in my logbook, anyway, not far out of Lincoln and I can remember later on my wife came out to live in Lincoln. I remember we sought a doctor up in Lincoln in private practice to try and get some treatment for this sinusitis and you’re leaping right now to the end of the war. At the end of the war I was posted to air ministry, movement’s branch and I still had sinus problems and so I thought I’d seek the advice of the air ministry doctor. I got a good guy there. His advice was, ‘Well we can drill, we can drill a hole through the roof of your mouth for drainage but I don’t advise it. It may not be successful but if you had a couple of years in a warm dry climate that would do you good,’ and as a result of that I had a medical post for an extended period of two year service and I went, of all places, to Palestine of course but after that to Kenya but I’ll talk about that later on.

DE: Sure, yeah.

RJW: Anyway, coming back to 1942, during the ops period the intruders started following aircraft coming in and landing and so air crew were billeted out. We were sent to small holdings. I was sent to a small holding, an absolutely delightful elderly couple who had strawberry fields there. Very nice indeed. I spent one night there. I told them, ‘Take the payment but I’m not going to be here. If anybody wants to know, oh yes I’m here but I’ve gone to town.’ And with a friend of mine, Mick Hamnett from 83 Squadron, we found a couple of rooms in the City of Lincoln pub in, in the centre of Lincoln and whenever possible we actually spent the night there. It was quite a pub. It was run by a lady by the name of Dorothy Scott whose husband, Lionel I think his name was, was a nav, was away in the RAF as a navigator. Anyway, it was an air crew haunt. At the back of the pub she had converted what had been a store room into a very cosy bar and that was where air crew from various squadrons accumulated. In fact at the end of 1942, towards the end of 1942 my wife came up and we, we lived there, lived out there. Unofficially of course. And one night while we were out there was an incendiary raid on Lincoln, huge chandelier flares and the City of Lincoln was hit with a fire bomb, particularly our bedroom but the local fire brigade did far more damage with their water then the actual firebomb. Anyway, coming back to the ops period, I’m sure that you’ve heard all these stories before but of course we were bounded with rumours and things like that. The first thing we heard was that oh the vicar of Scampton did a hasty retreat when war started because he was a Nazi spy [laughs]. The other story was of the policeman who was standing at the erm, at the Stonebow one evening and the aircraft were taking off, going off and he made a remark to a passer-by, ‘It’s going to be pretty hot in Berlin tonight.’ It so happened that they were going to Berlin and he was removed. But the other story, well whether that was true or not I don’t know but the other tale which is perfectly true. There was a hotel by the Stonebow called the Saracen’s Head which we called the Snake Pit for some reason. Very good. Good food. You could get a steak there. Very nice. There was a barmaid there by the name of Mary. She was a New Zealander and she was older than any of us. She was probably late thirties, early forties. She was a charming lady and she had an amazing memory and she was our local post box because we’d been to OTUs either to Upper Heyford or Cottesmore. We’d got pals on that and then we were posted to squadrons around, different squadrons around Lincoln and you wanted to know how your pals got on and you could, you could tell her. She knew, you know, you know that George Smith or somebody would say, ‘Did he get back? He was on 44 on Waddington.’ ‘Oh yes he’s alright.’ All this sort of thing you see and the story goes and I think this is in one of Gibson’s books that at the time of the 617 training at Scampton Mary was lifted out of the bar and sent on some paid leave down at Devon. I don’t know whether you’ve heard that story before. Yes. It’s written down somewhere but I can tell you that that wasn’t a rumour. That was true. The other delightful story is really good. In those days there was a lady entertainer by the name of Phyllis Dixie. She was a fan dancer. Probably the first stripper in England right, and she was performing at the Theatre Royal. Some lads, some air gunners got hold of a twelve volt acc and an aldis lamp, got themselves up into the Gods. The end of the act was the dear lady removed her fans strategically as the curtains closed and they shone the aldis lamp [laughs] which I gather was true. Anyway, going on from Scampton and Lincoln I was posted, I was sent on first of all air gunner instructor’s course at Manby. Came back from there and instructed at Wigsley and then sent to Sutton Bridge on a gunnery leader’s course. I did rather well on the course simply because I think I was able to drink as much beer as the course instructor [laughs] and we, I got an, I got an A which meant I was a gunnery leader A and when I came back to base the gunnery leader said, ‘Oh you can’t be a, you can’t be a gunnery leader A, you can’t be a gunnery leader as a sergeant. You’d better apply for a commission. Fill these forms in.’ So, this is true. It was incredible. I filled the forms in and I said something about, ‘Oh I can’t remember,’ and he said, ‘Oh don’t worry about it they don’t check anything,’ he said, you know, I thought this was a bit casual. Anyway, anyway I did remember what was necessary and my interview, however I was, I had a sort of an office, well not really an office, a place, kept stores [?] and things like that where I operated from. Schedules of flying and things like that looking after air gunners as an instructor and one day a little guy came in, in to my office with some papers and in some flying overalls and one of the epaulettes was flying down like that so I didn’t know what he was actually and he started asking me questions about the, about the commission you know like, ‘What’s your father do?’ And that sort of question, you know. Anyway I suddenly looked at his other shoulder and he was a wing commander and it was the famous Gus Walker and this was before he lost his arm. I was on the station when some incendiary bombs were, no photoflashes or something, something went wrong with an aircraft out in dispersal and he rushed out from flying control in a van to try and get the crew out and the bombs went up and he lost his arm. He was a hell of a nice guy. So informal it wasn’t true. I think he became an air marshal, air chief marshal or something. A big rugby referee. And I think that’s about all I can think of that of that era but then when I went to, when I, yes when I was commissioned, commissioned, gosh when was it? Probably the end of ‘42 beginning of ’43, almost immediately I was sent back to Sutton Bridge as an instructor instructing gunnery leaders and then we stayed there. Oh well that was quite good. We had a number of Polish pilots who were really very good pilots and we did a lot of low level flying quite illegally. There was one stretch where a road and the canal and a railway was spanned by high tension cables and if you felt like it they’d fly underneath them if they could and pray they weren’t found out. But these guys were really, really low level and we used to, we had a front, there was a guy in the front, we were flying Wellingtons mainly, sometimes Hampdens but mainly Wellingtons and put a guy in the front turret and aim for a group of trees you know [laughs]. Dear me. Those were the days. And then we moved station from there up to Catfoss and there when I was at Catfoss my pilot, old pilot Ralph Allsebrook came back, landed one day and said, ‘Jimmy, I’ve joined 617 Squadron. It’s a special duties squadron.’ We didn’t know, I didn’t know anything about the, we didn’t know about, it was before the dam raids but we didn’t know what they were doing but he said, ‘I’d like you to be in the crew.’ So I said, ‘Yes. Good. Fine.’ I was a flying officer by that time and so I said, ‘How do you go about it?’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘Leave it to me, I’ll push the buttons and see the CO.’ Well he did but they were adamant that I wouldn’t go. He said, ‘No, you can’t go. You’re an instructor, a trained instructor here. We want you as an instructor and,’ they said, ‘In any case Trevor Roper is the gunnery leader of 49 Squadron. They don’t need two gunnery leaders. So I didn’t go. Ralph wasn’t on the dam raid because I don’t think he was finished training, whatever it was but he wasn’t on it but much later on he was on another raid, I think it was the Kiel Canal and many of the aircraft were lost including him. It was bad weather I think mainly. So I was lucky again, I didn’t join them. But I did get a bit fed up with not, not being allowed to go back on ops and we had a guy, one of our instructor’s, fellow instructors, a chap called Griffiths I remember, he went to, left us and went to Bomber Command headquarters I think it was. Either to Group, no, it was Bomber Command headquarters that’s right and he came back, he visited the squadron one day and I said, you know, ‘Could you get me a squadron?’ You know. And he said, ‘You want to do a second tour Jimmy?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I wouldn’t mind doing a second tour.’ He said, ‘Yeah, leave it with me.’ So I got posted to 192 Squadron at Foulsham. I got, I got a rollicking from the CO at the, at Catfoss because of the gunnery wing, CO of the gunnery wing. He eventually found out that I’d, I’d wangled it through Griffiths you see but anyway I went. I arrived on the squadron which was fairly newly formed. It had been a flight before. I can’t, off the back of my head I can’t tell you the details of that but it was a flight and it had become a special duty squadron. It was doing radar investigation. We carried special operators. They were civilians dressed in RAF uniform just in case they were prisoners of war and at the same time David Donaldson joined the squadron. A hell of a nice guy. And it was a very happy squadron. We shared it with, I can’t remember the actual number of the squadron, six something, six hundred and something Australian squadron shared the station with us at Foulsham. A bit primitive but it was alright and I had about fifty gunners. We had two flights of Halifax 3s and a flight of Wellingtons and we also had some Mosquitos and a couple of Lightnings and we would fly with main force, carrying bombs of course. Not all the time but we did carry bombs and we were endeavouring, or the special duties operators were endeavouring to discover radar frequencies and wireless frequencies on which the enemy were operating. Early warning systems and the fighter aircraft they were using and that sort of thing. It was quite interesting. All highly secretive. They had a lot of gear set up in the centre of the fuselage and it was all screened off with canvas. You couldn’t get at it and you couldn’t get any gen out of them about what happened, but it was pretty good. We initially we flew as a crew. The leaders David Donaldson, Roy Kendrick the navigation leader, Churchill, he told me his name was Churchill actually, he was the signals leader I remember that. Anyway, and Hank Cooper who was the head of the special, the special duties guys and anyway, and myself as gunnery leader and 100 Group put a stop to that because they decided that if they lost the aircraft they lost all the leaders so we were “invited”, inverted commas to occasionally fly with a crew that might have been a bit dodgy to try and put a finger on if there was a weakness. So from flying with the very best pilot on the squadron suddenly found yourselves with the worst one but it didn’t amount to anything. It was ok. I didn’t have any scary times. My logbook shows the trips I took. We did the normal things with the main force. I didn’t do any Berlin ones. A bit late in the day for that I think but they were the ordinary trips that everybody else was doing. Oh well, there were occasions. We did stooge off from main stream. I think the theory, the theory was that if, they didn’t mind if we attracted the odd fighter so they could find out what they were operating on. Now look, here’s is a really good story. We had on the squadron a pilot by the name of H Preston [?] who was quite a joker. I flew with him on a trip and we got diverted on one occasion to a station down in 3 Group. Stirlings I think. And we had the usual eggs and bacon breakfast and all that sort of thing and we wanted to get back to base in the very early morning and when we got out to the aircraft we had quite a lot of air crew on the station walking around it because we had antennae sticking out all over the place, you see. So Hayter-Preston was asked about a particular thing that was coming out of the back and he said, ‘Oh well,’ he said, ‘That’s marmalade.’ They said, ‘What?’ ‘Well haven’t you got that? They said, ‘No, he said, ‘What does it do?’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘If a fighter comes up behind you and that’s turned on, it stops their engine.’ ‘Oh,’ he said. Anyway, off we went back to base and went through briefing and about half way through the morning a loud shout from the CO’s office, ‘Hayter-Preston’s crew to my office immediately.’ Off we trot to his office. David Donaldson said, ‘HP, what’s all this thing you’ve been talking about down at,’ wherever we were.’ ‘I don’t know sir.’ He said, ‘I’ve had Group on to me.’ He said, ‘Crews down there are on to their CO, been on to their Group, been on to 100 Group.’ He said, ‘They might have even got the Bomber Command, I don’t know, but they all want marmalade.’ See. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I was pulling their leg.’ [laughter] Anyway, we walked out of the CO’s office, walking off. David sticks his head out of the door, ‘HP. Why marmalade?’ He said, ‘Well I thought I’d be topical because we’ve been doing jamming.’ [laughs] You know.

DE: Of course. Yeah.

RJW: I did find, I must say I found my second tour very much easier than my first tour. Mind you I was privileged I suppose, in actual fact. I recognise that but it was a time when all the heavies were going. The raids were very heavy indeed but I didn’t, I didn’t seem to run into any trouble at all. Anyway, we were, we were flying on the very last trip. I flew on the very last trip to a place called Flensburg which was very near to the something lunars, is it? I can’t remember the name. The place where the armistice was signed on the Danish peninsula on the night before. The idea was to make sure they signed it. We were one of the last aircraft to return and there’s always been a bit of a fight as to who was the last aircraft over the target in the war. All I can say we might have been one of them. [laughs] Anyway, war ended and we started having, we started taking station personnel on tours. Flying, flying over the cities and back again. We did two or three trips. We landed over there at some of the stations. Went to Northern Germany and I don’t know, somewhere in Denmark I think in actual fact. We were taking people and coming back. Anyway, by about the middle of, probably a bit later then by the middle ‘45, July maybe, something. I don’t know. We were being posted to various parts and we were asked what would we to do. Anything we’d particularly to do before we were demobbed and so I said I’d like to be a, what do they call them, Queen’s courier, you know, King’s courier. That’s right. Thought that would be interesting. No. No. Can’t do that. Eventually I got sent to Air Ministry in High Holborn in the movements branch. It was at the time when there was some big food crisis going on and lots of VIPs were going backwards and forwards to America and we were finding aircraft from Blackbushe to get there. We were dodging around all over the place setting up aircraft, setting up things. Anyway we, I was there for a while and I was conscious of the fact that my sinus was still with me so I thought I’d take the opportunity to get the, unless I’ve already said this.

DE: Well you said you’d come back to it so, yeah.

RJW: Oh I see. I’d take the opportunity to get the air ministry doctor people to say what I could do about it and one of them suggested that they could drill a hole through the roof of the mouth which was painful and not necessarily successful and he did suggest a warm dry climate would probably heal the perforation. Anyway, eventually I signed on for an extra two years and I was posted overseas. Of all places my initial posting was to Palestine. There I was, there I was air movement’s staff officer, they called me and I was secretary and chairman of the air priorities board. Because there was a lack of civilian passenger aircraft we were providing passages through UK for the army, navy, air force and the other government people. The Air Priorities Board would look at applications and give them the priorities as they needed them and that was the job that I was doing. I remember I was, we had our officer’s mess and the hospital overlooking the mass cityscape [?]. The whole city was out of bounds to us which meant of course we went there [laughs]. At various times we had to be armed and it was quite, quite a time in actual fact but the one big thing that did happen we had a number of atrocities by the Stern gang and the Ernham vi [?] Lohamei. They were trying to get rid of the British. Didn’t seem to be any trouble between the Arabs and the Jews. It was the Jews and ourselves and they were pretty aggressive. Anyway, on one, we had our Air Priorities Board at army headquarters which was in the King David Hotel and one day I was being driven up there to an Air Priorities Board meeting and there was a loud bang and big piles of smoke went up and my driver said, ‘I think we’ll turn back sir.’ I said, ‘Yes, I think we will.’ And of course it was the King David Hotel that was bombed, sent up and a lot of army people were killed, and civilian people. Great tragedy actually because so I understand and read that the Jewish guys that did it they stuck bombs in milk churns and they actually ‘phoned and told them that there was bombs there but they said ha ha you know, took no notice of it. Very bad. Anyway, after a while I angled for a posting to Kenya. My brother was there. What had happened to him was he had joined the war, joined the RAF before the war and he was a fitter 2E. He’d been to St Athan’s and he, early in the war he was posted to the Far East. The ship was torpedoed off Mombasa and he got ashore and he was sent to Eastleigh there and he stayed there throughout the war. He married there, English girl there and so he was there and after the war he joined an aircraft company. East African Airways I think but he was a, he became a senior engineer, became chief engineer of a Safari Airways eventually. So I angled for a posting there and I got it. They called me SMSO Senior Movement Staff Officer. I knew nothing about, I knew about air movements, I knew nothing about road and rail. I signed an awful lot of documents [laughs] but I, you know, had no training for it at all. It was, it was a very nice posting. A very easy posting. Originally, we were billeted out in hotels but there was a housing shortage there and all that sort of thing and they thought as an example we ought to have an officer’s mess so an older hotel we took over we used it as headquarters and we had an officer’s mess set up and I can remember we had a very easy going AOC who was a non-flyer. Actually a peacetime guy but a nice guy, very easy going and he never seemed, never seemed to send for you in his office, he came to see you and one day he came to my office and he said, ‘Woolgar I’ve a job for you.’ ‘Yes sir.’ ‘I’m going to make you the mess secretary.’ I thought, ‘Well yes sir but you see I do have to go to Cairo once a month for conferences, air conferences and I also have to visit stations around, you know, Aden, Eritrea and places like that periodically. I am away from base quite a bit.’ ‘Oh, oh alright, I’ll think about it.’ So comes back the next day and he said, ‘Jerry Dawkins is mad with you, Woolgar.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Cause I’ve made him the secretary of the mess,’ you see, ‘But I’m going to make you the PMC.’ So I was the president of the mess committee and I knew nothing. I really didn’t know anything, you know. There was much older people than me, senior to me to do it but anyway they all dodged it and I couldn’t dodge it the truth was but it was interesting because it was in the days they did a lot of entertaining and this AOC he entertained the army guy, the naval guy and on one occasion the Aga Khan. I met, I met a lot of people. I don’t know whether I should put this on the tape but Mrs AOC was a pain in the head.

DE: Right.

RJW: The flowers were never right, or she sat in a draught, or the meat was tough, ‘Flight Lieutenant I didn’t like –’ [laughs].

DE: Oh dear. Oh dear.

RJW: But you know, you know I was only in my, I was in my twenties, middle twenties and I always thought it was good because it taught me a lot. It gave me experience which I never would have had otherwise. Anyway, eventually I went to Ein Shemer I thought I’d like to do a bit more flying. I went up to Ein Shemer in Palestine to join number 38 Squadron. I was the gunnery leader come armament officer, come radar oh everything. Everybody was leaving and they said, ‘You can do this.’ ‘You can do that.’ And a bit of a mixture I think but the main role of the squadron was finding illegal immigrant ships. Illegal ships were probably like what’s happening now but these ships were coming with Jewish people from the Balkans you know and from the middle of Europe and they were coming in to land in Palestine because the intake was on quotas and the idea was that 38 Squadron should locate them by radar on patrols and then get the navy to intercept them and when we did find them the navy used to miss them and they landed and the army picked them up. They put them in detention centres, that sort of thing, for a while but that is, that is what we were doing and I was there until about August, August 1947 and then I came home. Do you want to hear what happened to me after that?

DE: Yes, please, yeah, yeah.

RJW: Well I came back to the Hove Corporation. They’d promoted me to become the assistant valuation officer. I wasn’t qualified. Two hundred and fifty pounds a year. God. [laughs] Salary. And I realised I had to become qualified quickly. There were two exams. The Chartered, Chartered Auctioneers and Estates Agent’s Institute and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, so I got my head down and fortunately both organisations and others I believe, they introduced special war service conditions. I was able to take the direct final which was good. It was a three year course but I did it in eighteen months. Ah yes. I put my family, my wife, my daughter through hell because we didn’t do, I didn’t go out, I didn’t do anything. I just studied because I realised that I wouldn’t get anywhere unless I did and having passed and become a chartered surveyor I marched off the council and said ah you know and they said, ‘Ah well yes, we don’t think you’ll be any more service to us as a chartered surveyor than you were before Mr Woolgar.’ Twenty five pounds a year increase in your salary and we’ll give you a grant of twenty five pounds towards the cost of your studies. Well that prompted me to search for another job and I was very fortunate. I went to, I secured the job of the senior, a senior valuer in the city planning department of the City of London. So from knocking the hell out of Germany I came back to rebuilding the fire bombed city which was very, very interesting. It was a fantastic job in actual fact. I dealt with Barbican, St Paul’s area, all the war damaged areas. I was fourteen years there. I — I eventually I was deputy and the boss left and I got his job. For five years I was the planning valuer of the city and it was really good but that’s a whole book.

DE: Yeah, I can imagine.

RJW: About what happened. Various things, lots of public enquiries, you had some very famous people of course and QC’s and things like that and we had a New Zealander who was the city planning officer called Meland[?] and he was a very informal guy. Not a bit like the city fathers were and his famous words were, he was under cross examination by a QC at a public enquiry and he was asked why it was necessary to compulsorily acquire a group of buildings to put a road through and he said, ‘Well you see the bombs didn’t always drop in the right places.’ [laughs] You know. Anyway, after, after fourteen years I was poached by a firm by the name of St Quintin Son and Stanley to become a partner there and to be responsible for all their planning work and that was very good, very interesting because I, having negotiated with the partners as the valuer for the city I was now negotiating with my deputy who had come up on the opposite side. He often said, ‘Yeah but Jimmy you said, so and so'. I said 'Oh well yeah' [laughs]. But that was, I’ve had a very, very interesting life really. The city was full of tradition. Full of everything. That’s a whole book really. Having dealt with Barbican, the redevelopment of Barbican, the city —

DE: Yes.

RJW: I was now dealing on behalf of developers for developing other parts of the city. The idea, the main idea the city leased most of its land out on ninety nine year building leases by tender. So the developers all had to make a tender, ground rent condition and the design of the building and that sort of thing. That’s really the way it worked and from time to time there were planning enquiries and I was instructed sometimes by clients as a valuer, as a planning valuer to deal with various appeals for land, on land that they wanted to develop which the city didn’t want them to and or they were local protests and got myself in the witness box and highly cross examined by very clever QCs but also roamed around the country because we had a lot of clients in the city that were elsewhere in the country. We acted for the Bank of England, we acted for the Stock Exchange and the, and quite a number of the banks, Midland Bank and Lloyds, people like that and so it was, it was all done at a high level. It’s kind of amusing some of the things that I was asked to do which I knew nothing about [laughs] and I always remember a firm Denis firm [?], they were in the sand and gravel business they always wanted to extract sand and gravel from the best agricultural land by rivers you see and there was always objection to it. Anyway, I fought one or two appeals for them quite successfully, fortunately, and one day the chairman asked me to value their mineral reserves and so, ‘I can’t do that, I’m not the minerals man. I know nothing about it.’ ‘Oh that doesn’t matter,’ he said, ‘I just want, I just want you to value it for me.’ I said, ‘Well I don’t know how to value it.’ ‘You’ll find a way.’ I particularly wanted to do it and I got the impression that we might lose them as a client if you know, if it didn’t [?]. My junior partner and I we put our heads together and somehow or other we found a way and he said, ‘Ah, it doesn’t matter. Nobody else will challenge it because they don’t know the way either.’ [laughs] Anyway, we, what did we do? Well leisurely [?] we, during that time the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors celebrated its hundredth year. I had a bit of a role in that as chairman of one of the committees that dealt with it which was very interesting. Oh yes. I was, I was picked up by a building society and became a non-executive director. It was called The Planet, and over the years, I joined them about 1963 I suppose, as soon as I became a partner of St Quentin and over the years we merged with the Magnet Building Society, that’s right and then we took over a midland society that had called itself the Town and Country Building Society so we then adopted that name and eventually, for the last three years I became chairman of that. I had the most interesting time because we had overseas conferences. Notably one in Washington which was extremely good and oh and Cannes. They really looked after themselves these that was the international thing you see.

DE: Wonderful.

RJW: Very nice, very pleasant and during all this period we had various dinners in the Mansion House, dinners in the Guildhall and in 1971 St Quentin firm celebrated it’s sesquicentennial which is their hundred and fiftieth year.

DE: Thank you for telling me.

RJW: Yes. Right. So by that time we were three joint level senior partners right and we split up the duties of what we were going to do. We had a year. I got the job of having the dinner in the Guildhall. I was manager, because the city surveyor was a friend of mine he managed to get us, we were the first outside body to have a dinner in the Guildhall and we had it and got the governor of the Bank of England as a principal guest, Lord Donaldson, the Master of the Rolls, Lady Donaldson his wife who was to become, he was the sheriff at the time and it was a pretty high ranking do. It was very good but I’m telling you the story because it’s kind of amusing. We had a chap in the firm who looked after all those sort of things you know. He was very good. He got the nuts and bolts done for us. So I said to him, ‘I think you’d better go tell the police up at John Street Police Station that we’ve got some VIPs coming to the Guildhall on this particular date because they might want to take some precautions. So he takes the guest list up, goes up to John Street. He sees a cockney desk sergeant and this desk sergeant looks at this list and he says, I’ve forgotten his name now, the governor of the Bank of England, ‘Oh no he don’t rate.’ Master of the Rolls. ‘Oh no he don’t rate.’ Lord something, I don’t know and he went down and at the bottom it had Her Majesty’s Band of the Royal Irish Guard. ‘Oh my Gawd,’ he said, ‘George, got the Irish Guards coming. Full emergency.’ And because the Irish guards, it was at the times of the troubles and because the Irish Guards were coming they had all sorts of precautions. These chaps had to come in individually in civvies and all that sort of thing you know, by themselves and yeah. I thought that was rather amusing.

DE: Crikey.

RJW: Anyway, I retired in 1971, no 1973 that’s right. 1993 at the age of seventy three, got it right. We spent a lot of time cruising. We like cruising. We went on quite a few cruises. We got, we had a place in Majorca, an apartment there. A little place on the coast which was very nice. We spent quite a bit of time out there. That’s really it. Just got older. A bit more infirm, you know. The wheels don’t grind as well as they used to. I hope I haven’t bored you.

DE: No. It’s been absolutely wonderful. There’s —

RJW: I haven’t given you an opportunity to ask any questions.

DE: Well, I’ve as you’ve seen, I’ve jotted some questions down. I mean, again they’re quite, quite broad questions. What, what was it like flying in a Hampden?

RJW: Well you see, strangely enough there was no comparison was there because I’d flown in an Anson which was alright but the next type aircraft you flew in was a Hampden so it was, it was alright. Probably thought all flying was like that but for the wireless operator, rear gunner it was a bit dicey I think. People don’t really know this, you have a wireless set in front of you and what they called a scarff ring with twin VGO guns with pans of ammunition on them, right and a cupola which closes down over the top of it over the guns but in order to operate the guns the cupola has to be back which means when you’re over the other side you’re in the open air and you were standing up to be vigilant. Well I mean you couldn’t see sitting down. You wanted a turret standing up and eventually you have an electric motor on it but originally there wasn’t. It was [unclear]. There was a heating pipe came off the starboard engine I think, exhaust or something. Unfortunately it used to burn the living daylights out of you down on the ground and it was ice cold when you got up top [laughs] but you know. So it wasn’t that comfortable and the other position, the rear gunner was in a belly thing. A blister underneath and that was very, very difficult. You were hunched up, you know, you would get cramp in it. It wasn’t very nice but you know other than that it was alright although I must admit that when I mention to people, RAF guys, I was in a Hampden they say, ‘You were in a Hampden?’ They say, ‘You flew in Hampdens and you’re still alive.’ [laughs] No, no, no. They weren’t, they weren’t that bad really. I think our pilot like any, Ralph, he was quite happy with it. I don’t know whether the navigator was. Sorry.

DE: No. No. That’s, that’s wonderful. So what was, what was your favourite aircraft to fly in?

RJW: Sorry.

DE: What was your favourite to fly in?

RJW: The —

DE: What aircraft was your favourite to fly in?

RJW: The other aircraft.

DE: Yeah. What other aircraft?

RJW: Oh well I flew in Halifax 3s. Wellingtons. I think I flew in a Mosquito once or twice. Ansons. Passenger in a Tiger Moth. That sort of thing, you know. Oh and Lancaster, Manchester. Manchester and Lancaster yes but I didn’t do any ops in a Manchester or Lancaster. The Manchester was the forerunner as, you know about that. Yes. Yes. We had them on, they were introduced on 49 Squadron in about, I think about September 1942, something like that. One of the early ones and then fairly quickly replaced by the Lancasters. Oh the Lancaster were marvellous. I flew in the Lancasters of course in Ein Shemer. They were Lancasters. Yeah.

DE: I see, right, yeah.

RJW: They were good. We had, at Ein Shemer I’ve got to tell you one of the duties there was to provide an airborne lifeboat at Malta so we had a little jolly there for three weeks and so. A couple of aircraft with airborne lifeboats stationed at Valetta. You were on twenty four hours standby. Then twenty four hours down the pub [laughs] that was quite good and we did one, we did one exercise, the exercise was that we were taken out by the navy, cast adrift in a dinghy and the other crew had to home on it and drop the airborne lifeboat and the crew in the dinghy had to get in to it and sail it back in to Valetta harbour. We were the crew in the dinghy. We got told off for eating all the rations [laughs], but you know it was fun. It was quite good. Malta was nice too in those days. Post war you see.

DE: What was –?

RJW: Oh and Cyprus. That was another place we had to go to. We went to Cyprus. Yes. Sorry.

DE: What was, what was it like, what was the difference between being a sergeant and becoming an officer?

RJW: Oh well. It was quite good. It was more comfortable. The sergeant’s mess was very good. The food was always good. I never grumbled about the food. I think the air crew seemed to get additional rations or something. It all went in altogether but somebody once told me you get more dairy products because as air crew or something like that. I don’t know. But being an officer obviously was more comfortable. You didn’t have to make your bed [laughs]. You had a batwoman, batman or batwoman. You know a WAAF who did it for you. Cleaned your shoes that sort of thing. The chores. You had more chores done for you I found, but yes it was it was comfortable. Flying. Right. Oh I forgot to tell you an incident which is recorded in David Donaldson’s obituary. We were flying on patrols to locate the launching pads of the V2. In fact, we saw, I was with David Donaldson, we saw the first one go up and we got a fix on it and that is quite interesting because we told the special operator and he got his head down and we tried to get a lot of information out of him when we got back as to what he found. We got nothing out of him of course but of course what we did eventually find out and this is public knowledge now it wasn’t radar controlled. It was clockwork controlled but Churchill insisted that the patrols continued so even after they found out we were still going up and down on the line and on one occasion, daylight. It was on daylight a couple of, I don’t know what they were, I can’t remember, mix them up, I can’t remember what the aircraft were. A couple of German fighters. I can’t remember what they were now, a couple of German fighters came up, come up and we were just about to take evasive action when they tucked them in, they tucked themselves in the wing and the pilot went like that.

DE: Waved at you.

RJW: Waved at David. David. You know. Like that. Like that and then they peeled away and off they went. This was over Holland and they were quite friendly. This would have been, oh I don’t know, probably March, April something like that 1945. And do you know I remember that so well for years and years and years and I wonder sometimes did that really happen or did I dream it? And then in David Donaldson’s obituary it was mentioned and I thought goodness that is true, it did really happen. I meant, I should have told you before.

DE: No. That’s, that’s wonderful. What was, what was David like?

RJW: Yeah. Actually of course they’d, if they’d, if they’d have split up you know they would have, they would have had us you know, in fact.

DE: Sure.

RJW: Yeah. Yeah.

DE: What was David like?

RJW: Sorry?

DE: What was David Donaldson like?

RJW: Oh lovely. He was a hell of a nice guy. Easy going. He was a good CO. Firm, right. Never panicked. He was a solicitor by profession and he was very calm. We did the first FIDO landing at Foulsham. We went to Gardenia [?] and did our stuff there and incidentally on the way back, was it Balcom [?] Island, the Swedish island on the Baltic, fired various tracer bullets up in a V sign [laughs]. Nobody went near of course. Anyway, when we got back it was fog and David said, ‘Well we’ve got an option of landing on FIDO or being diverted.’ He said, you know, he said, ‘What do you want to do chaps? Do you want me to land or go somewhere else for your eggs and bacon.’ ‘Oh no David,’ you know and he did a perfect landing. Real, you know. The risk of FIDO was that you veered off it but, perfect. Yeah. He was like that. He said, ‘What do you want to do?’ [laughs]

DE: Wonderful. Yeah. So when you saw these two fighters —

RJW: Yeah.

DE: Were you mid-upper upper or were you the rear gunner?

RJW: Sorry?

DE: Were you mid-upper gunner or the rear gunner? When you saw the two fighters.

RJW: Yes.

DE: Were you the mid-upper gunner or the rear gunner?

RJW: I was in the mid upper.

DE: Ah huh.

RJW: Yeah.

DE: Was that your –?

RJW: I was, yeah because I, the mid upper was the controller, in other words we used to take evasive action. If you were in daylight you take evasive action and once you had come back you’d take control. You would tell him corkscrew right, corkscrew left because the pilot can’t see.

DE: No.

RJW: They can’t see. They come in on a curve of pursuit like that and you’d corkscrew in, down and roll and up the other way you see, but if they split up either side you’d had it.

DE: Yeah. Did you did you ever fire your guns in anger?

RJW: Hmmn?

DE: Did you ever shoot at a fighter?

RJW: Ever see a fighter?

DE: No. Did you ever shoot at one?

RJW: Oh yes.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: At night time. Well I hoped it was a fighter [laughs]. No. Once or twice you know you saw the thing come out of, but never, I never had a sustained fight. Never had something come in two or three times but I can’t remember. Not on the Halifax. Never had anything on the Halifax or the Hampden. Fired the guns several times on the Hampden but I can’t remember exactly when they were. Sorry about that.

DE: That’s quite alright. Yeah. Yeah. Did you, which did you like better the night ops or daylight ops?

RJW: Oh we didn’t do much daylight. We did very little daylight. We did some mining in daylight but it was nearly all night ops. We always thought daylight was a bit scary but [laughs] but no I suppose the scariness really was in the middle of the flak. Then you really, in a Hampden you could hear it, you could smell it and you could see it. Puffs of puffs you know if you got there. If you were — Essen and Hamburg they were, they were the places that you got, and of course Berlin but I only, I only did one trip to Berlin. My first one. But that wasn’t very good because it was covered in cloud anyway. If you, when you, when we went to France, if we were bombing France if you couldn’t see the target, initially anyway, you had to bring your bombs back and that’s recorded quite a bit.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: By the way have you got “The Hampden File?”

DE: Yes.

RJW: Harry Moyle?

DE: No. Yes. We’ve got a copy of that.

RJW: That’s very good. Have you got, “Beware of the Dog”?

DE: I don’t know about that one.

RJW: 49 Squadron history. The whole history of 49 Squadron written by John Ward and Ted Catchart. It was actually published by Ted Catchart. If you get in touch with Alan Parr, you know Alan. He’ll tell you where and how you can get a copy of it. You should really have a copy of that.

DE: Yes.

RJW: Because that details everything.

DE: Yeah. Wonderful. I will do. Thank you.

RJW: Yes. It’s called, that’s our crest you see.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: Cave Canem.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: So —

DE: Yeah. I’ll make sure we get a copy for the library.

RJW: Yeah.

DE: Yes.

RJW: Yeah. And the “Bomber Command Diaries.” You’ve got those.

DE: Got those. Yeah.

RJW: Yeah. I’ve got all those.

DE: They’re worth, worth a bit as well, they are as well. How how did you cope with flying nights?

RJW: How did I cope?

DE: Yeah. Flying nights. What —?

RJW: How?

DE: Flying operations at night how, how —

RJW: Finding them?

DE: Yeah. How did you, how did you cope, you know with interrupted sleep patterns and —?

RJW: I’m not quite with you sorry.

DE: No. Flying operations at night —

RJW: At night time.

DE: Yeah. Your sleep was interrupted.

RJW: Oh sleep.

DE: Yeah how, how did you, how did you —?

RJW: Oh well yes you went to briefing in the morning if ops were on. No not briefing. You’d do a bit of exercise and that. Go to the flight and then you’d have an early briefing and then you’d have a rest, have your eggs and bacon and then night time you kept awake. There were tablets they used to give you to keep awake. I can’t remember the name of them now but they didn’t do much good I don't think. And then of course after de-briefing when you came back, eggs and bacon and you had a long sleep. Sometimes you were on the next night but not very often that happened. Not in my day. It did later on of course.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: It did later on.

DE: Did you, did you take tablets to keep you awake?

RJW: Yes.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: I can’t remember the names now.

DE: Wakey wakey tablets.

RJW: Yeah. I can’t remember what they were. Caffeine. Yeah I think it was —

DE: Yeah.

RJW: Something like that. You could, if you wanted them you could have them but I can’t remember the name of them.

DE: Was it, was it Benzedrine?

RJW: Yeah. Yeah but I never found. You were wound up. Let’s put it, let’s be honest about it. Everybody was. You were apprehensive.

DE: Yes.

RJW: Ok. You knew the target. You kitted up. You went out. You were taken out to the aircraft and you fiddled around with all your gear. You had to make sure everything was ok and eventually you took off. Sometimes you often, sometimes you took off in twilight so you could see the setting sun as it were, you know. See Lincoln Cathedral. And because you were in the rear you were looking west you were seeing some of the light and ok you got a bit of jitters maybe you know. A bit. Apprehension more than anything else but you had to be very alert. Very alert. You had to be watching all the time and you reported back anything you see. Getting over the target, doing the bombing run. That was a bit of a wait you know. Flying steady, straight and steady and hearing the navigator or the bomb aimer going to the skipper. Everybody else was quiet. You could see the activity going on but if there was cloud below or the flashes coming up and everything else. If you were near flak as I said you could smell it and see it and all that sort of thing. Got away from the target. There was always a sense of relief once you come away from the target but of course it was just as dangerous coming away. You couldn’t — you couldn't relax or you shouldn’t relax, let’s put it that way. Probably that’s what did happen. You just had to be on your toes all the time but on the way back over the sea, over the North Sea coming back you were a bit relaxed then. Coming in to land of course you had to be very careful. You could have intruders, you know. You really, you couldn’t sit down. You couldn’t take a rest. And you know there were times and I’m sure others have told you this, you had a very dicey trip and you say, ‘If I get back I’m not going to come again.’ [laughs] Why come back? If I get out of this one that’s it, but you did, you know. You didn’t, you didn’t think much about, you didn’t think too much about it on the ground. At least I didn’t. You didn’t dwell about it. You didn’t think. You got wound up for ops. Then they were scrubbed so you were off to the pub you know it’s not oh, everything goes and you just, you just tended to live for that night, that night. You were in the pub with your pals drinking away and you didn’t give many thoughts to the fact that you would be doing the same thing tomorrow. At least I didn’t and I don’t think many other people did either. Some might have, but I didn’t. You just treated each day as it came along. You got scared, of course you got scared you know, got scared out of your life when you were in the dinghy but you thought, oh well, you know, something will happen. I’ll get out of it. Eventually you did. I don’t know but the greatest thing [?] was though, to be honest was to see your pals go although because in the main you didn’t know whether they were killed or not. They didn’t return. They were missing. Right. Failed to return. And there was always the hope that they’d be prisoners of war or they’d landed somewhere else but it, it didn’t sink in. It wasn’t like that, being in the army and seeing the person next to you killed. That didn’t happen unless your own aircraft, you could see an aircraft gosh I can’t remember the number of lucky breaks I had. Yes. On the, on 49 Squadron when I first joined Allsebrook I was a bit concerned and this is not against the guy at all but it is recorded somewhere this happened. He came to the squadron. He had flown into a balloon barrage under training and he was the only one that got out. On the first trip with him he was very keen, they’d made him the photographic, he wasn’t the, he wasn’t the station fellow, he was some sort of, something to do with photography and he wanted to hold the aircraft straight and level over the target to take the photographs [laughs]. So you know that was my first trip or second trip, I can’t remember which and I got a bit, a bit concerned about it and there was a sergeant pilot, or flight sergeant pilot that I’d been drinking with or knew quite well and he wanted a rear gunner and I thought, he wanted a WOP/AG, I thought. Well ok I’ll go and see if I can get switched into his crew and I went to see Domestra [?] who was our flight commander, Squadron Leader Domestra and he he said, ‘Oh no, I’ve done the crew schedules for the night,’ he said, ‘Come and see me tomorrow.’ His name was Walker this chap. He took off behind us. Engine cut. Went straight in. The bombs went up. Killed them all. I thought, I didn’t know it was him at the time. I saw it. When I got back we said, ‘Who was it that went, that went in?’ It was him. I thought oh my God, you know. Strange isn’t it? I must have somehow had a lucky penny. Oh yes and you will have heard this story and Eric will have told you. Others will. We had, the CO was called Stubbs. Wing Commander Stubbs. One day after briefing for ops, we were going on ops. ‘All the NCO’s will remain behind,’ remain behind. We got a real right rollicking about our form of dress, not wearing regulation boots or shoes. All sorts of things you know. Slovenly behaviour. Then he said, famous words, ‘Just remember the only reason you’ve got three stripes on your arm is to save you from the salt mines in case you are taken prisoner of war.’ Have you heard that? Oh yes. Yes. Yes. He said that. He said that and he got the name of Salt Mine Sam. Sam Stubbs. That is recorded somewhere but Eric Cook he was with me. I was on the squadron when Eric Cook was there you see and but he famously used to quote that quite often actually but yeah and it’s quite well known. There was a guy that was, I don’t know what his name was now but he was, he was an honourable bloke, honourable, he was a sergeant pilot and he was a bloke, he was an odd bloke, he refused to take a commission. I can’t remember his name but he was some sort of landed gentry of some sort and he was able to talk in high places as you did and we got a very meagre, half-hearted well it wasn’t an apology it was some sort of, you know it wasn’t really meant sort of thing you know. Sorry about that.

DE: No. That’s wonderful. I’m going to, I think I’m going to draw the interview to a close because you’ve been talking for nearly two hours.

RJW: Oh gosh. Have I?

DE: Yeah. That’s —

RJW: Have I really?

DE: Yes. Yeah.

RJW: I’m sorry.

DE: No, it’s –

RJW: I’ve probably bored you stiff.

DE: No. It’s absolutely marvellous and I’ve said nothing on the tape so it’s fantastic.

RJW: Eh?

DE: I’ve not spoken at all. It’s all been you so —

RJW: Do you, it’s funny everything else is going but that memory.

DE: It certainly is. Yeah. It’s fantastic. Yeah. Well I’m going to –

RJW: And while I’ve been talking to you Dan I’ve been living it visually.

DE: I could tell. Yeah.

RJW: I can see it.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: I can see the incidents right there.

DE: Yeah.

RJW: As you know.

DE: It’s been an absolute pleasure.

RJW: I didn’t realise, I didn’t realise it was —

DE: Two hours look. So I shall, I shall press pause and stop it. Thank you very, very much. That’s absolutely wonderful.

RJW: On our seventieth wedding anniversary my grandson stood up and said Papa, Reg, Jimmy because they had all three, all three generations there. Sorry. Sorry.

DE: Ok. So this is an interview with Reg Jimmy Woolgar at the International Bomber Command Centre in Riseholme Lincoln. It’s for the IBCC Digital Archive. My name is Dan Ellin. It is the 14th of June 2016. Reg. Jimmy. Just for the start of this tape could you tell me about your early life and your childhood before you joined the RAF.

RJW: Well before I joined the RAF I left school in Hove and I joined the rates department as the junior clerk and it was really the office boy who made the tea but I became a valuations assistant in the valuation department there before the war and started to train as a surveyor and in 1939 on the 8th of December I went to the Queen’s Road Recruiting Office and I joined the RAF and there I was in a few days on my way to Uxbridge with about five or six other guys all from office appointments. When I joined I, like everybody else who wanted to join the RAF, I wanted to be a pilot. Well I actually went to the Queen’s Road office in September and they wrote to me and said, ‘We have an influx of pilot training but we can take you as air crew.’ I went to see them, asked what that meant. They said, ‘Well you will fly as a member of an air crew.’ I said, ‘Well can I ever become a pilot?’ ‘Oh yes,’ they said, ‘Once you’ve trained as air crew you can become a pilot.’ But of course it never happened because it just seemed to be that whenever I, wherever I went I eventually became an instructor and after being trained as instructor they didn’t really want me to be a pilot or anything else so I concentrated on doing wireless operating/air gunnery. That really is what happened to me before the war. Is there anything else you’d like to know?

DE: Well, yeah. What was, what was training like?

RJW: Pardon?

DE: What was training like?