Interview with Frederick Donovan Say

Title

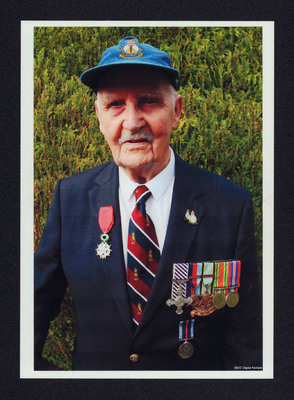

Interview with Frederick Donovan Say

Description

Frederick Say went to Tottenham County High School and when he left school he went to study agriculture. He joined the RAF and was posted to RAF Tangmere and worked in the Operations Room as a clerk and was promoted to Leading Aircraftsman Special Duties. From here he was posted to Headquarters 10 Group. He was recommended for aircrew and after initial training in Babbacombe was posted to Canada for training in navigation, gunnery and bomb aiming. On his return to the UK he was posted to 196 Squadron where he and his crew commenced bombing operations, completing 29 and a half operations. After completing his heavy conversion training he was posted in June 1944 to 514 Lancaster Squadron as a bomb aimer and took part in the bombing operations in support of D-Day. Before leaving the RAF he worked in the Motor Transport section at RAF Watnall.

Creator

Date

2017-07-12

Language

Type

Format

02:10:26 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

ASayFD170712, PSayFD1705

Transcription

CB: My name is Chris Brockbank and today is the 12th of July 2017 and I’m with Don Say in Highnam in Gloucestershire to talk about his life and times. So, Don what are your earliest recollections of life?

FDS: Being bathed in the tin bath by a lady with a red rubber, I think it was a rubber, I don’t know, red apron in front of the fire. Not [laughs] not too close obviously. And that was not my mother actually. My mother had died from what’s the official name of it? Hypocalcaemia. Not familiar with it? Milk fever. It’s an imbalance and in the days when it wasn’t unknown, it was known, cows get it. And when they get it its caller staggers and they stagger. And that’s the symptom for adults. I didn’t know my mother in other words. I have letters you know. A letter to my father. But she would be about twenty two. He would be about twenty one or twenty two. He had been in the Army. His picture’s somewhere over there on that table. You can see it facing you. Facing you.

CB: Right.

FDS: He was in the Machine Gun Corps. Underage so his mother got him, pulled him out and the army pulled him back in again, and he still stayed in the Machine Gun Corps. He finished up managing flour mills, flour and feed mills in Newcastle upon Tyne. But he’d be about twenty one or twenty two then. So I was then in the care for a few months I think with two old ladies who’d been in service who were some sort of relative, although I didn’t know them. And then my mother’s cousin and her husband started to look after me very well until I was, I don’t know, somewhere between five or six years old I think, she died. And eight years later my guardian as he became married again to a lady who said, ‘I’ve been a wicked woman.’ I said, ‘Yeah. I’ll drink to that.’ That was at her bedside visiting. I would have done too. Very unpleasant. There was much, much more cruelty by the tongue than by the lash. Can be anyway. It’s very difficult. It accounts for my aggression. Aggressive attitude to life [laughs] it may do. I don’t know. Blame somebody anyway. The current habit as well. So where have we got to now?

CB: So we’ve got to —

FDS: School.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Well, I passed, passed the various exams and left what was called then Tottenham County Grammar School err County High School. There were three schools. Boys Grammar, Girls High School and the whatever the next. That was called the County School. It was brand new with virtually an entire graduate staff. And quite a privileged education, finest court and the rest of it. And playing field. I was not a boarder and at no point did I feel any great loyalty towards it. Nor have I since. But I did pass school cert. Whatever it was called. Matric or something. And I also took, I was taken by my guardian to what we would we call him now? Careers advisor I suppose. And he said, ‘What do you want to do?’ I said, ‘I don’t know. I know what I don’t want to do. I don’t want to be told what I’m going to be doing all the time.’ So I said, ‘Agriculture sounds like a good bet.’ And I then took an exam and went to the what was then the Herts Institute of Agriculture, but now College of Agriculture, which was financially each year of half roughly horticultural training, half agriculture. And the [pause] they were a good staff. I didn’t work very hard there. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Fell in love with my first girlfriend. Needn’t, needn’t put that down. Long since dead. It was near St Albans. About two or three miles. On the edge of the airfield. I’m trying to think of the name of it.

CB: Radlett.

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: At Radlett was it?

FDS: No. No. It was their private, err, manufacturers of aircraft.

CB: At Hatfield.

FDS: Pardon?

CB: Handley Page at Hatfield.

FDS: No.

CB: Well —

FDS: We’ll get through.

CB: De Havilland at Hatfield and Hand —

FDS: It was quite an important flight path.

CB: Handley Page

FDS: It’s over the College of Agriculture.

CB: Right.

FDS: Or it was.

CB: Right.

FDS: I’m trying to think what.

CB: Well, de Havilland at Hatfield and Handley Page at Radlett. Anyway, we’ll come back to that.

FDS: It’ll come back to me suddenly.

CB: Ok.

FDS: In the middle of the night. I’ll give you a call [laughs]

CB: Yeah, do that, yeah [laughs]

FDS: Tomorrow morning [laughs] But it’s relevant because I went there as a student and many years later I applied and was interviewed for the job of principal and then I discovered that the flight path. The first one was right on the flight path of the thing so I turned it down.

CB: Right. Ok.

FDS: Great fun.

CB: So you were at the college for how long?

FDS: A year.

CB: And then what?

FDS: I went, this is a bit I [pause] I went to, I worked for a local farm. When I say local, in Hertfordshire. I don’t remember it particularly. And eventually the principal went for a change of job and he said, ‘Well, I don’t know if you’ll like it but it’s a job of hedging for a man called Patterson,’ at [pause] near Salisbury somewhere he thought. It wasn’t. That was the one at Petersfield, in fact and the name of the chap was Rex Munro Patterson, and he was the nephew of Lady Alliot Verdon Roe who was the wife of Sir Alliot Verdon Roe, and I went there to go hedging and he interviewed me and he said, ‘You’re not doing hedging. You’re going to tidy up the farms that I’m renting.’ He, don’t write this bit, his aunt had lent him a thousand I think to start with. He’d been to Canada, brought back the idea of the buck rake which she gave to Harry Ferguson and he worked in tandem and he had about twelve farms over Hampshire and Sussex. Is that a coincidence?

CB: Extraordinary.

FDS: Sir Avro.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: And his son used to drive the lorries to go and collect heffers from Liverpool and bring them down to Hampshire. I used to go. Go with him. He would drive. He was about a couple of years older than me.

CB: That was a long journey.

FDS: Good fun. Heffers had never seen people before very much and they showed it. But he, Patterson was novel in the sense that he introduced the buck rake. But he also, he didn’t introduce he shared the introduction of [pause] what do you call them? I can’t think of the name of the damned things now, towing cow, cow units. Mobile units.

Other: Milking units.

FDS: Yeah. Across the Downs trying to —

CB: Mobile milking parlours, were they?

FDS: Milking. Yeah. They were on wheels. We used to, one man and a boy or a young man and a young, two young men rather, and I worked for that because I got fed up with the office and I was working outside. They were short on cattle and we had about sixty or seventy per two men which was quite remarkable then in those days. The land, a lot of the land he rented at about five bob an acre from Sir Phillip Ricketts. Ricketts Blue? So he had large lumps of Hampshire and Sussex and my life seems a circuit around that doesn’t it? That’s how I came to get to Portsmouth and join the RAF VR.

CB: So, we’re talking about now 1938 going into ’39.

FDS: I’m, I’m dodgy on the dates.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Dates and months. About that time.

CB: And you were eighteen in 1938.

FDS: I had to be eighteen to join.

CB: So, how did you go about joining the Forces? So, how did you go about joining the Forces?

FDS: I joined.

CB: Yes, but how did you do it?

FDS: Well, I, first of all I went to the Recruiting Centres, and I went to the Army first. They gave me a tongue lashing and turned me down.

CB: This was in Portsmouth was it?

FDS: Yes. Then I went to the Navy. All on the same Saturday [laughs] and then I went to the Royal Air Force who said, ‘Yes, thank you. Do you want to fly?’ And I said, ‘Why would I want to do that?’ I said, ‘All I want to do is to have something that’s a bit more lethal than a pair of boots for the invasion,’ which was supposed to happen at any minute. But I couldn’t take it seriously. I never did really. I changed my job, you see. I can’t remember quite why, but I went to Essex. Wickford In Essex, and I worked on a farm there for [pause] it must have been the three months before I was called up, because I was feeding the pigs and my friend who was staying with the people we were staying with at that time came round on his bike and said, ‘There’s a telegram. It looks important.’ And I looked at it and I said, ‘It’s vitally important. I’m needed to save the country three days ago.’ “You will report to Southampton,” three days before I received it. So I got on a train. You know, you do as you’re told. I went to the farm and I said to the farmer, ‘You can come back.’ I said, ‘I don’t think it’s very likely. I don’t think it’s very likely because, I think I might join the Air Force. I don’t know.’ Anyway, I went down and reported to Glen Eyre Road, Southampton [pause] and the chap there said, I said, ‘Where am I supposed to go to now? You’ve recorded that I’m here.’ ‘Go over there with that lot. You two come with me.’ And we two of us followed him out to a vehicle, and he drove us around various, a house, ‘How many bedrooms have you, madam?’ I think the poor woman said, ‘Two or three,’ or something. ‘Right.’ They’re not awful?’ No. ‘Well, these two are staying here overnight. Not, will you? You board them overnight. They’ll be picked up in the morning I can promise you.’ So we were there over night at Glen Eyre Road. That’s it. No. That was the Centre. We were despatched from there to this house. Picked up by lorry and it gets ludicrous. It gets ludicrous. In the morning we got in to a lorry, the back of a standard RAF lorry and we drove to Tangmere. I didn’t know it was Tangmere. We drove through the guardroom and straight through. And there would be, there were fifty four of us. I think that’s right. Work it out yourself because the sergeant who used to be on the door of the local cinema had been recalled and he came up and said, ‘You lot,’ we were fifty four. ‘Three lots of eighteen,’ So there’s three lots. Then he had a piece of chalk. They could afford chalk. He carefully drew rectangles around each eighteen and I was in the first group. ‘You’re A-Watch, You’re B-Watch and you’re C Watch.’ And we said, ‘What precisely are we watching?’ ‘You’ll find out.’ [laughs] We were then marched off to a hangar and given bed boards and a pallias. You never had a pallias.

CB: No.

FDS: And straw. Put the clean straw in the pallias and what the hell do we do with this? Shaped vaguely like a musical instrument. A big one. You put these, anyway we kept there the other end of the hangar suddenly blokes came in in what appeared to be riding britches. Classy reservists. Six foot five airmen doing the same thing but the other end. And this corporal that was running this, this corporal or sergeant came around again. I said, ‘What are we supposed to be watching?’ He said, ‘You’ll find out.’ Marched off along a pathway and down a slope into a room. Guess what? Operations room. We were operations room clerks and three weeks to three months later I moved from AC2 ignorant general duties to leading aircraftsman SD, special duties. ‘Now, whatever you’re told in here and whatever you see in here you’re not to communicate with anybody in the fear of death.’ We did, oh eight or twelve stretches and they found out rapidly that very, all that was happening the convoys were going up and down to the Channel and 605 City of Birmingham Auxiliary, 43 Squadron which I think at that time there I think they were the Gladiators because Number 1 were the Hurricanes. Number 1 Squadron. Halahan was the boss. They were pushed off fairly rapidly to France. To a base there and did a lot of jobs when we ran away from [laughs] when we ran away from the Germans at Dunkirk. That was a lot later. But that was quite interesting to me. Lloyd. A chap called Lloyd from Lloyds Steel Pipes. Flight Lieutenant Lloyd. It was a millionaire’s squadron and didn’t they flaunt it? You know. Silk flying jackets and riding britches. Totally amateur. And relatively few other ranks. There were these fifty four of us divided into eighteens and then about eight were sent off to the wireless centre and what was there? We were shoving counters. Shoving counters around and putting things up for, instead it became enemy blocks of a hundred or two hundred aircraft but originally it was boats. Ships. And these were the convoys and the aircraft and they were sort of went out and did their patrols. And that was very exciting. We sat there, nothing happened. The Observer Corps were at the other end of the lines. They came in to us and you know that you’ve seen all the, have you? You’re familiar with the ops room set up.

CB: Yeah. Yeah.

FDS: The map.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Well, there’s a sector map and the platform behind us. I don’t think there was any rank there normally under the rank of about flight lieutenant or squadron leader. And because we were near London we had visitors. Churchill. Churchill didn’t spur me on but I heard that he’d come down and been in the ops room and said that he thought it should be largely peopled by women and oddly enough I agreed with him. And they came in then. WAAFs came through. All frightfully, frightfully nice girls. I wrote a poem to one. Shall I tell you it?

CB: Do.

FDS: Her father appears in “Who’s Who.” I’m afraid I can’t introduce you. For an addition you need a commission. Three rings with the minimum two. She might take a cocktail with me, or come out to afternoon tea, but remember that you are a mere AC2. It makes all the difference you see [laughs] on an AC’s pay. Oh dear. I had nothing better to do than write silly rhymes. That was true, the girl.

CB: Excellent.

FDS: But they were awfully decent and one of them was called Bolton. Mary Bolton. Now, that’s relevant because guess what? She became the mother of Dyson.

CB: Oh.

FDS: I knew Dyson when he was that high and I was, I knew her sister was in the nursing order. I did a eulogy for her about a couple of years ago. Sheer coincidences. At that time we didn’t know it was a coincidence obviously. It was renowned for the excellent entertainment we got because we got all the shows from London and stars and anybody that thought they were anybody with power came to see us if they were allowed in. All shhh. Very secret. Well, the Germans knew. They knew where the, what do you call it? Radar units were because they came over and thoroughly bombed them after I left. Up to that point I was still getting it. I was then posted from there. I said, ‘I want to be out of here although it’s very interesting and very active with convoys and the like.’ I left and went to 10 Group and they promptly bombed Tangmere, did the Germans. Smashed it up and they had to relocate the ops room. I, by now at 10 Group, I didn’t know it was 10 Group. I was in a tent. We were in tented accommodation and some bloke came around. I don’t know. A flight sergeant. It didn’t mean anything to us. We don’t do any station duties. We were special duties. Shush. [laughs] So, I shared a tent for a few months. That ultimately became, it’s now the, what is it? I don’t know the stratospheric centre for, you know battle. It’s deep underground. There was masses of caves. I take it you know that. That county is riddled with caverns and one of them was 10 Group. And the chap who used to fly opposite, was it Hullavington on the opposite side? There was an airfield on the opposite [pause] 10 Group was on a hill. Not on a unit. And the air base was on the other side and the [pause] Park. Park who was on Fighter Command at one point used to fly in in his own little Hurricane. All white. White overalls and shouting and pulling, pulling rank. Stayed about two days and went again. And that was quite interesting for a while but I got bored with that and I was doing night duty and the chap [pause] who was commanding then? Baines. Wing Commander Baines. You had a wing commander who was ostensibly in charge of the ops room, and then the other, there was the Army, Navy and so on and you see them. And I was one of the little erks running about in between, and Baines was on duty that night. He said, ‘I’m bored.’ I said, ‘Well, join the club.’ No sirs or anything when we were off duty. We were on duty but relaxed and I said, ‘I’m bored stiff with this job actually.’ ‘What would you prefer to do?’ I said, ‘Well, I see these blokes walking out from aircraft and they don’t like any brighter than me. So, I’ll be aircrew of some sort.’ ‘I’ll recommend you.’ Which he did. And I went to, at that time I think it was a bit of an unusual entrance. I went to, what was the Air Force base? What is still the Air Force base? Headquarters.

CB: What? Bentley Priory?

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: For fighters?

FDS: London. No. The London office.

CB: Ad Astral House.

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: Ad Astral House.

FDS: I don’t think it was called that then. Anyway, I was sent there for an interview. To be interviewed for aircrew and I was waiting outside in the passage way and a chap passed me full of rings up his arm and I didn’t know how he got, a large ring and lots of small ones. ‘What are you doing there my boy?’ And I said, ‘I’m waiting to be interviewed, sir.’ ‘Are you nervous?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ So he said, ‘Well, don’t be, he said. ‘They’re no brighter than you. Thirteen times thirteen.’ I said, ‘A hundred and sixty nine.’ He said, ‘If you know that [laughs] wonderful. Air Commodore JB Cole-Hamilton. Yeah. Nice chap. Pleasant. He said, ‘Go ahead. You can pass that.’ There was no such thing as [pause] they had centres didn’t they in London and elsewhere for direct entry? And I was being slotted in with direct entry and you could pick me out, because all the others had new uniforms. I had a green great coat. It had gone green when I was in the tent. Sort of gone blue green [laughs] and I was posted. Posted from there. I’m trying to think of the next stage.

CB: Where was the selection centre?

[pause]

CB: Where was the selection centre?

FDS: It must have been. I went to Babbacombe. That was new. They had just taken over the hotels.

CB: Right.

FDS: And I was based in a hotel at Babbacombe with several other blokes. I was UT aircrew. UT pilot. They got fed up with that later on. They couldn’t get any aircrew. Everybody was going in to be a pilot. So they took, took a chopper. I think I wasn’t any good as a pilot. I wouldn’t have made a good pilot. And I came to the same conclusion that they came to. So I went to Torquay and did initial training, ITW, that would be wouldn’t it? Based in a hotel there. And then from there we were, we sat, when we were shipped up to Scotland. I think I went up to Scotland then. I’m not sure at that point. I went to Scotland. It’s come up at a different points. Is this making sense?

CB: That’s fine. Yes.

FDS: I think its fine thus far.

CB: Ok.

FDS: Where am I now?

CB: So, you’ve gone to Scotland.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: That’s to get on a boat is it?

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: That was to get on a boat.

FDS: Yeah. Yeah. And I went to the orderly room which the others sprogs didn’t know much about and said, ‘Say, where am I? Am I posted?’ ‘Yes,’ he said. I said, ‘Where am I posted to?’ And he said, ‘South Africa.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to go to South Africa. Where else is there?’ ‘There’s Canada.’ I said, ‘I’d like to go to Canada.’ He said, ‘I’ll swap you over.’ [laughs] Absolutely. That’s it really. So we were all lined up. The people going on the boat. I think they were about five hundred in the end and we were all lined up on parade, me in my green great coat. The Duke of Gloucester whose time [laughs] I met him much later on life, but he was around stinking of beer. He came round and was due to inspect us. And the chap in charge, whatever he was, of the parade walking down looking at all the airmen all standing to attention and he got to me [laughs] green coat. ‘What do you think you’re dressed in?’ ‘I beg your pardon? This is my issue.’ ‘Well, where have you been?’ I said, ‘Where I’m sent. To a tent at one point. That’s where it went greenish.’ ‘Go over to the stores now and get a new coat.’ And I was sent to get a new coat. It was incredible. I went over on the [pause] doesn’t really matter. It was a liner anyway. A cabin. And I had my first large bar of chocolate for a long time I remember. I remember two merchant seamen who were crew I think were going out to be crew to come back having a fight outside [laughs] in the whatever it’s called. Passageway. Incredible. And we came in to, came in to Canada. Which port? It was while it was still in those days it was still non-alcoholic. What did they call it?

CB: Prohibition.

FDS: The state that we landed on was a non-alcoholic state. So the first two civilians I saw were three staggering drunks [laughs]. Lots and lots of whatever it’s called. I can’t remember now. Illegal booze anyway.

Other: In the US.

FDS: Hmmn?

Other: In the United States.

FDS: Canada.

Other: Oh, in Canada.

FDS: In Canada at that point. In that State. I’m trying to remember the name of the state. It starts with an M. Manitoba? No. That’s west. East. Eastern Canada. Where you land. Or you did land anyway.

CB: Well, a lot of people went to Newfoundland, didn’t they?

FDS: Yeah. We, my lot didn’t because we went to the other bit.

CB: Ok.

FDS: I’m trying to think what it was. I think it was M [pause] When I came back it was still alcohol free. Whatever the word is.

CB: Was it?

FDS: I came back through the, by now it was a big unit. When I went out it was just a base. Nothing was there. We were put on trains. A three day train journey. Very exciting. Old trains you know. You could climb right up the ladders and black gentlemen seeing you on and off them. And three days we were on the train. We got marched off every three hours to make sure we didn’t get too constipated. And we were there two or three hours I think. Stopped. Marched around a bit. Lounged about a bit. You needn’t write it down but I was invited when I went back. Not to me personally. There were three births as a result of those stops. I went back again more than a year later. This was what I was told believe it if you will. I could believe it. We were all white flashed people. The story went around that the people with white flashes in their hat that had unmentionable diseases. That was the story they floated. The other, the non-white flashed people. Quite amazing. Yeah.

CB: So you got on the train three days.

FDS: On and off it for three days.

CB: And where did you end up?

FDS: Very well fed. Calgary. Calgary Airport [pause] which had part of it as an EFTS, and I did a hell of a lot of EFTS and I did a, I got as far as the, I did as far enough to get as far as what’s his name? CFI. And he downed me. Well, he downed me officially. I was told this is only in the last six months. I wasn’t relating this, I heard it related that they had so many pilot applicants ‘38 ’39 they couldn’t cope and they were overdone and they couldn’t get any aircrew so they just chopped off a convenient lot. Which they had to do. So whether I was part of the excess or not I don’t know. Anyway, I went there and I enjoyed that. We used to fly up to the Rockies at the weekend. It was very good.

CB: So you saw the chief flying instructor and what did he do?

FDS: Failed me.

CB: And?

FDS: I was disgruntled. I was disgruntled. It was all very civil. I was called and said, ‘You’re being released.’ That’s all. ‘You’re going to the navigation school.’ I said, ‘Please sir I don’t wish to go to a navigation school. I’d like to go back home now. So, if I can’t do this I will go as an air gunner.’ ‘You won’t. You will do as you’re told.’ Oh. So I was very bad tempered. I went off to the railway station with full kit. Kit bag. All sorts. I’m not sure I didn’t have a gun. Didn’t have any ammunition that’s for sure. I had a gun. I think. Anyway, I climbed on to this train, threw my kit in the corner and found I was accompanied by a beautiful red headed girl about my own age. And we were together for three days because she went off, she was going on one stop further than me. I got invited for the weekend, which was rather nice. So, at weekends of the war the war stopped for us in Canada. Stopped at weekends. It was rather nice. They’d come and get in the car.

CB: Where was this nav school?

FDS: Hamilton, Ontario which you know. I failed my first exam there. Don’t write that down. I failed it quite deliberately. I was sent for an interview. ‘Your little game is to fail and be sent back. It won’t work. You will be here if necessary until you’ve got a beard down to your knees.’ [laughs] I know that, I know you can pass the exam. You know you can pass the exam. Go and pass the bloody thing.’ [laughs] So back I went, but I was back a course all the time as a result of that. So, where are we now?

CB: So there we are in nav school. So what —

FDS: Still at Hamilton.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Anything interesting happen? I flew round. We flew all over the place. Up to Muskoka looking for a chap who got lost off a formation with Harvards. He got lost in the snow and if you get up to Muskoka and up in that direction it’s about a thousand lakes. We didn’t find him. Whether he was found eventually I don’t know. But he, how he got lost off a formation. That’s what they told us.

CB: So when you were at nav school?

FDS: Interesting.

CB: What was the course content?

FDS: DR nav. Well, we’d already done DR nav anyway so we did DR nav. Lots of cross country. Well, it seemed lots of cross country. They’re logged in here and there. I can’t remember how long it was. They were just about coming up to the point where the Royal Air Force had a fit of the tremors and invented Nav Bs. So navigators who didn’t do bomb aiming and bomb aimers who didn’t do navigation, which was pretty damned stupid but if you were lucky like me [laughs] pilot, a third, a third of the pilot’s course, about all, all of the nav course. The whole. I went to bombing and gunnery at Picton. Picton. Where was Picton? Is it in the back of the book I wonder?

CB: We’ll, we’ll stop in just a mo if we may, but what were you flying when you were getting your navigation practice?

FDS: Anson. I flew with a chap called Warrant Officer Orville and he said, ‘We’re running out of fuel and I don’t know if we can get back very easily. We’ll have to land.’ We landed on what is now the main highway. The trans-Canada highway. Goes up north. We landed on it [laughs] Cars and things came to us and brought petrol [laughs]

Other: Orville.

FDS: As I recall he had a big moustache. I was sat behind him. I had to feed him chewing gum to watch his moustache going up and down.

CB: He was a Canadian, was he?

FDS: I don’t know.

CB: Oh.

FDS: I think he, I think he was English.

CB: Ok.

FDS: He seemed fairly English. But you used to go, you could orbit Hamilton and you could see the, what was the American town down the bottom of the lake? You could see the lights on there very clearly. In no circumstances would you go over to the, to Niagara. So, I’ve got a picture of Niagara Falls taken when we weren’t supposed to go there. We all went there obviously but they weren’t in at that point. They came in in that December I think it was, was it?

CB: So we’re in, that was ’41. So, what time are we in now? We’re in 1941.

FDS: I’m in —

CB: 7th of December ‘41 the Americans joined.

FDS: I’m not [pause] if I have a look at that.

CB: We’ll just stop for a mo and have a look.

FDS: I might have a look because people flying the drogue.

CB: People flying the —

FDS: The drogue.

CB: Yeah. The tug. Yes.

FDS: For gunnery.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Were people who’d been on the pilot’s course with me.

CB: Oh, were they?

FDS: Several people. ‘What score would you like to get?’ Well, of course you can’t get a hundred percent if you were gunning. In gunnery not likely you would get much more than five. I said, ‘Well, I don’t want to get close enough to see the scissors on it but I’d like to get a few shots at it.’ An impossible score. I had to go up and do it again. He got a rocket for being so close.

CB: Oh right, yeah.

FDS: All very decent fun really.

CB: In your gunnery training what did they do to begin with to train you?

FDS: I don’t remember it very much.

CB: Were you using on the ground shot guns or what did you do?

FDS: Oh yes. Yes, we used those. A chap called Henty who’d shot at where ever the famous rifle shooting is.

CB: At Bisley.

FDS: Yeah. He’d been a Bisley shot. Henty. Yeah, we did rifles. I can remember using a revolver because we [laughs] when we shouldn’t do we went in a Nissen hut and we had a lot of marmalade tins and put them on a fence and you could use what was that little, don’t put that down for goodness sake. You could use sten ammunition.

CB: Oh, sten guns right.

FDS: But that ammunition would fit the revolver.

CB: The 9 millimetre. Yeah.

FDS: Yeah. Incredible. Naughty boys. We had a smoking chimney [laughs]

CB: Not 45s.

FDS: Shot the, shot a revolver up the chimney. Flames and smoke coming out the chimney. They could see it, of course. Dear oh dear.

CB: So, they let you get away with some of these things.

FDS: Oh yes. The Royal Air Force for me was fun from the minute I started the ops room with the latter part of the ops room was. The first bit was interesting but not much fun. I didn’t think anyway. I mean moving counters a bit. Knowing where a ship was and an aircraft it could absorb you for the first day or even a week, but it’s not, and mainly men at that point on the other end of the phone lines, Observer Corps.

CB: Right.

FDS: Yes. It was Group Headquarters I was moved to. I don’t know why. But —

CB: 10 Group. Yes.

FDS: 10 Group. I don’t know why. I don’t even know if I’ve not entered. I didn’t enter any of that did I?

CB: No. Let’s go back to Picton, Ontario.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And your bombing and shooting.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Gunnery were at the same place.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So we talked about the gunnery. What, what were you flying in when you were doing the airborne gunnery?

FDS: I can’t think. Oh, we had a VGO. Vickers gas operated isn’t it? So it was a cockpit, open cockpit at the front or back?

CB: Was it?

FDS: I can’t remember. Instructor would be generally at the back of a two seater thing so presumably I’m right aren’t I? VGO. It stays in the mind. Vickers gas operated machine gun.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Used to get stoppages. Well famed for the number of stoppages.

CB: It didn’t like the draught.

FDS: I wonder what it was. Oh I know. The thing. They shot a load of them down at the beginning of the war.

CB: Oh, they were —

FDS: Battle.

CB: Fairey. No. No.

FDS: The Battle would it be. Would it be the Battle?

CB: They could have been Fairey Battles.

FDS: I think it probably —

CB: Because they lost so many to begin with.

FDS: They shot a hell of a lot of them down. Yeah.

CB: The light bomber. Yeah. The Fairey Battles they put to Canada.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Vickers gas operated machine gun.

CB: Right. And then bombing.

FDS: You could almost count them coming out.

CB: And bombing. Yes. Bombing. How did they teach you bombing?

FDS: How? Well, they had a good, they’d got a damned good simulator. You did hours on a simulator similar to, not identical with pilots but similar, and you bombed that and you also [pause] That would be it, yeah.

CB: Did you not get any live bombing with the Battle? With the Fairey Battles.

FDS: I don’t think so. No. I think that would be, they had six practice bombs. Whatever different. I have that. I don’t know if I would enter that. Would I enter it?

CB: We’re just pausing for a mo.

[recording paused]

FDS: Chris, well, this is what made my voice go high is pollen. I’m trying to [pause] Watson, Watson, Watson. Oh dear, eight bombs. Wellington. That’s, no that’s an OTU. 20 OTU, Elgin.

CB: Yeah. That’s a bit. We’ll come to that in a minute.

FDS: Picton, Picton, Anson, here we are. There you are.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Results of the gunnery course. Results of the bombing course.

CB: Right. Ok. That’s good. Thank you. Yeah.

FDS: It’s taking a long time isn’t it?

CB: So, you finished the course on bombing. You qualified on your navigation.

FDS: Yeah. It says so there.

CB: Does it?

FDS: Oh, very much so.

CB: So, because you were doing navigation, bombing and gunnery.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: You were the traditional observer.

FDS: Absolutely.

CB: So how did your graduation occur?

FDS: It didn’t.

CB: So —

FDS: You mean when did I get my wings?

CB: Yes.

FDS: I think they were sent to me. I’ve never had a —

CB: So, you came to the end of the course is what I’m getting at.

FDS: Yeah. My award was different.

CB: Was there a parade?

FDS: Not for me.

CB: And everybody went.

FDS: I nearly always had something like scarlet fever, or a change a course or something. Something. I never finished with the people I was with.

CB: Oh right. So at that end of this.

FDS: I don’t remember doing so, anyway.

CB: At the end of the observer course how, what happened next?

FDS: Well, I think there was a parade and gave them my wings and then I did the Picton one. Much the same thing happened.

CB: So you got your —

FDS: You had a parade. No they had a reward.

CB: They did.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Why weren’t you on the final parade?

FDS: Oh God. I honestly can’t remember.

CB: Ok.

FDS: Nothing disgraceful.

CB: No. So, at the end of the training in Canada then what happened?

FDS: The end of the training in Canada. I’m trying to think where I came back from [pause] I had a great welcoming sign in this particular camp and it said, “The following premises are out of bounds for all ranks because of the [unclear] that had gone on. Well, they were made their own gin from wood alcohol which will make you blind, and some people were damaged by it obviously. So all ranks were forbidden. So, you probably ignored that. No means of implementing that anyway. And they weren’t all thieves and robbers fortunately. I have never ever been on a Wings Parade. That’s an achievement. You just brought it to my mind. What a shame. Not really. Something always intervened.

CB: But you didn’t get any illness in Canada did you?

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Oh, you did. What did you get?

FDS: Scarlet fever.

CB: Right. Was that at the end of the course or when?

FDS: I was at Trenton at the time. No. I was sent to Trenton which was a hell of a big base. When was I sent to Trenton? I think this was how I came to miss wings or something. I had this, I was having an examination of some sort that was important and I sent my apologies and said, ‘I have an infection.’ It was a ring around the wrist. I thought it was. I didn’t think it was an infection. I said, ‘It’s just a sore ring but I’ve overslept but I’ll come and do it because I can pass.’ ‘You won’t.’ Looked at it. You’ve got scarlet fever. Oh right. You’ve got to go through —' they drove me off in a large posh vehicle to a civilian hospital. Put me on the ground floor. Put me in one of those silly operation gown things that buttoned at the back that wouldn’t do up and I had a room on my own. I said, ‘What’s going to happen now?’ They said, ‘Well, you’re going to be isolated for four weeks or six weeks’. I said, ‘Well, that’ll be nice won’t it?’ Anyway, they brought me no food so I rang my bell they came and they said, ‘What’s wrong?’ I said, ‘I’m out through that window if I don’t get some food. I’ve had no food since breakfast.’ ‘Oh. You’ll get some.’ So they brought some. It was terrible. I was supposed to be on a starvation diet. I don’t know. I was there about six weeks. That’s how I got an intervening bit missing things. They came and brought an me ice cream. The people who walked past the window. ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘I’m an Englishman imprisoned here.’ And they had a poor little kid in a room as it were over there. He was dying from [pause] what was it called, the horse [unclear] bug?

Other: Tetanus.

FDS: Tetanus. Yeah.

CB: Tetanus. Right.

Other: Lockjaw.

FDS: Because the chap who had to keep an eye on me was also keeping an eye on him and doing other jobs. He said, ‘I’ll leave this door open. You can see him. If he has any great problem or distress he’ll wave at you. That wasn’t very pleasant but there you are. They were all very kind. I got back and sent to Hamilton and of course everybody had gone. That’s how I came to miss. Right. I wasn’t deprived of wings. They could have kept me there for the next quarter though but I’d finished. There we are. That was Hamilton.

CB: So you travelled from Hamilton, Ontario back. How did you go?

FDS: From Picton?

CB: From Picton. And where did you go?

FDS: This you’ll find difficult to believe. I went to the holding unit. Whatever it was called. I don’t know what that was called. It was holding unit for entering and exiting Canada. It was huge by the time I left after a couple of years. But I went round from there to New York. New York, guess what I came back on. The Queen Mary. I get bounced about don’t I? I was the only observer of the four hundred and ninety nine pilots and me. And five hundred American nurses, and about five thousand Americans. And they put a guy, put a bloke with a gun on the door for these [unclear] I said to one of them, I asked the Yank, ‘What’s this bloke armed for?’ I said, ‘I’m going to be armed if they’re going to walk around armed.’ He said, ‘I don’t know really.’ I said, ‘Nothing, there’s nothing there would tempt any of us [unclear] if he’s unarmed. [laughs] They said, ‘You will get one meal a day once we leave harbour.’ And once we left harbour they were all being seasick. You could get food any time you liked. And the Queen Mary came in to Scotland and I came down from Scotland to Bournemouth. Stayed at Bournemouth for six weeks or so waiting to be posted and it was a Canadian unit, it’s a Canadian run, very nice. Good summer. I went down to the local pub there and there was a Wren there and I thought I know her. And I said to her, there was nobody else about, so I said, ‘Don’t get frightened.’ Nobody else there. I started off with a very unusual line, ‘I know you.’ And she said, ‘Yes. I know. I know you from when I was down at Tangmere.’ Tangmere, near the coast. We used to go to the coast and she was one of the girls I met with because most of the entry were local blokes. My, my other seventeen companions were nearly all local. And that’s how, you know they introduced you to the local girls and boys you know. Quite interesting. Jean Marsh that was. So I had her companionship for a short while and guess what? Where I went next? I’m damned sure it’s next, Scotland isn’t it?

CB: For the OTU.

FDS: OTU.

CB: Ok. So, where was that?

FDS: I’ve got the unit in mind.

CB: Elgin was it?

FDS: Pardon?

CB: Was it at Elgin?

FDS: Yeah. No, Lossie.

CB: Lossiemouth, Ok.

FDS: I met a CO of Lossie about couple of meetings [unclear] ago. I’m right aren’t it?

CB: Yeah. Lossiemouth first.

FDS: Which one was it? 12?

CB: Well, you —

FDS: Was that 12th ?

CB: That was 20.

FDS: Well, it was 12 that I went as a staff member later on. We haven’t got very far have we?

CB: We’re doing alright. So you had two OTUs. You had —

FDS: No. I went to the other OTU as an instructor.

CB: Oh right.

FDS: Between tours.

CB: Ok, yeah.

FDS: Which was the normal.

CB: Yes.

FDS: But I got off it in five months because I posted, I posted myself as you will see. I applied for a posting and I’ve got a letter there if you can read it and it says I’m applying for instruction in new instruments and it says, “No permission. No.’ Exclamation mark. ‘This man has been only been off five months and cannot be spared.’ He actually put on it. [unclear] He went off on leave that week and I went to the orderly room and I said, ‘Is there [laughs] is there a spare posting?’ They said, you know, posted. They said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘I’m off.’

CB: So where did you go next?

FDS: Where am I now?

CB: So you’re at the OTU. What did you do at the OTU? You had to crew up first.

FDS: Oh yeah. That was when one of the Royals flew into the hill and got killed didn’t he? They were, what they were doing they were using —

CB: The Duke of Kent.

FDS: Wellingtons until they were knackered and then they put them on to OTU where they were even more knackered and that’s what happened. He was on training I think, very sad.

CB: The Duke of Kent. Yeah.

FDS: It was. Yeah.

CB: So, you got to Lossiemouth. What? How did you crew up?

FDS: Just stood around in a heap as usual. They were crewing up and I crewed up with Alec Watson. I must be, I want you to be very, very careful and scrupulous. I’m sure you will be here. If I say he, he became a bit diffident in sight of a target. He finished. He was all right. He didn’t go off LMF but they would have posted him off LMF if somebody had witnessed it I’m sure. He never [pause] he hesitated. But I should have thought that fifty percent of them hesitated.

CB: Are we talking about at the OTU?

FDS: Hmm?

CB: Are we talking about at the OTU.

FDS: Not at the OTU. At that point. No.

CB: Right.

FDS: Later on when I was training, when I was instructing at OTU he did bullseyes. What was a bullseye then?

CB: They were practice raids weren’t they?

FDS: Yeah, they were going out, tipping the, actually when 617 did their job I think somebody said no other aircraft? What a load of rubbish. I’ve got one veg which is down as a no sortie by some bloke. Six and a half hours. No sortie. I could have kicked him in the crutch. He obviously was not an operator. He just signed it, you know and said oh [pause]. Naughty that. Worst things that was done. But I crewed up there with Watson. The rear gunner of that crew was killed later. I could have found out how but I didn’t see anymore. I thought, well that’s being a bit morbid. The others survived their, that one tour so —

CB: So you became a crew at the OTU.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Was the, were you did the whole crew then go on to the squadron?

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So which —

FDS: I think. Can I — [pause]

CB: We’ll stop again.

[recording paused]

CB: So from the OTU you were posted to a squadron. What was that and what were they flying?

FDS: 196 Wellingtons. I’d better have that back again now.

CB: Where were they?

FDS: I remember. Hmm?

CB: Where were they flying from?

FDS: Just north of York.

CB: Linton on Ouse, was it?

FDS: No.

[pause]

FDS: Just as well it’s been dealt with as an archive, isn’t it? 196 May, Picton, ah [pause] December ’42.

[pause]

[recording paused]

CB: April ’43. Right. So, 196 was April ’43.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Right.

FDS: It says here.

CB: That was the full crew.

FDS: Ops Duisburg. Yeah.

CB: From the OTU.

FDS: Well, a full crew of five isn’t it? Ops to Duisburg. Oh, and gardening. Gardening looked like a soft option. It wasn’t. I can remember we went there. Six aircraft went gardening with a couple of mines and only us came back. And there’s six hours and five minutes. That’s not [pause] that’s rather a long time in enemy territory. There we are, and ’43, 196, May. Do we want any of those?

CB: Well, just to know what did you do in. What sort of raids were you doing in your Wellington with 196?

FDS: Killing people with —

CB: But where?

FDS: Mixed bomb loads.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Not very big bomb loads really in retrospect.

CB: But where were the targets?

FDS: Well, Germany. At that time, anyway. I don’t think they did anything. I’m trying to think of any others. I don’t think so. Dortmund. Oh, Dortmund. DNCO. Not Carried Out. Two hours fifty. Doesn’t say why, but it does say an air test. We did another one gardening. You see why I was allowed to go off on my own I think. There’s another one.? No you wouldn’t know the sortie. Six hours five minutes. Return from St Eval.

CB: Because gardening is mine laying.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And what height would you fly when you were dropping mines?

FDS: Well, above nought feet but not much above fifteen hundred. If you did it, if you did it very much lower they’d go off and if you did it much higher they’d go off. So they were always, we had a Naval chap come round and explained the fusing, very carefully. The [pause] we, we had bombs and things. You had two, two little cavities. One cavity had liquid in it and the other didn’t. Well, the one that didn’t was sent out and of course they’d drill and say, ‘Ah a one cavity bomb,’ and then they’d drill them again and bang it would go off. They altered them all the time. A fuse [unclear] Some of them, some of them pretty obviously were more or less instant which is difficult.

CB: You’re talking about the bomb disposal people dealing with the bombs when they were found.

FDS: Made it very difficult.

CB: Ok.

FDS: Return from St Eval [pages turning] 196, June, gardening Lorient, DCO. Return from East Moor, engine spare. Air to air bombing practice, air test, air firing. Here we are. 21st Krefeld. Two five hundred, seven small bomb containers, DCO. The 22nd ops Mülheim. Two five hundreds, seven small bomb containers.

CB: What governed the choice of bombs then? The combinations.

FDS: The CO. Well, the command group.

CB: But it was to do with the target was it?

FDS: Group would decide.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Well, if it would burn well they’d have more incendiaries.

CB: Right.

FDS: If it’s, I, I get the impression that if accuracy was the first call you’d have your armour piercing. So, at low level you’d have, well I’d hope they were long [laughs] long on weight, you know. Low level you didn’t do small bomb containers. Where are we now? Mülheim, Elberfeld, Gelsenkirchen. Five and a half hours. Five fifteen. Six ten. A long time isn’t it over enemy territory? June — ops Cologne. Four five hundreds. They did aim at legitimate targets, you know. The actual bomb. I don’t know if you’ve seen the bomb maps. Have you seen the actual, the night maps?

CB: Where the bombs are dropped.

FDS: Where the black, yeah.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Where there were, I’ve got some but I’m not sure where they are if you want. Oh. A Monica test. Yeah.

CB: So just describe Monica would you?

FDS: Oh, I can’t.

CB: So, that’s your tail warning radar.

FDS: They could pick us up very well.

CB: For night fighters.

FDS: They could pick us up very well. July — St Nazaire. Return from Chivenor. That was six hours forty minutes. Ops Cologne five hours. Advanced base Harwell. Gardening Lorient, six hours ten minutes. That was on the 5th. Gardening Lorient again.

CB: So you did quite a bit of mine laying.

FDS: Yeah. Did a —

CB: And how did you feel about that?

FDS: That was about the time, was that about the time they were trying to run the battleships, the German battleships —

CB: Yes.

FDS: Were trying to run up the coast.

CB: The Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau.

FDS: And we were trying to drop mines.

CB: In the way.

FDS: [unclear] relatively harmless bullets I suppose.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Because they all went off at different [unclear]. Watson, gardening again Lorient. Gardening Dutch coast.

Other: On a run was it, were you occupied all the time or were you —

FDS: Oh, yes. You were frightened from when you took off. Nervous shall we say. Yeah. Nervous before take-off because you could land at the end of the runway with a full bomb load which was not very comfortable. It happened the odd time. Then you were going around and around missing each other in the clouds if you were lucky and then you went at what? At ten thousand feet. You could be shot down over your own airfield. Some were.

Other: By whom?

FDS: Germans.

Other: Right.

FDS: They were only twenty minutes flight from Britain remember. They could get over here very quickly.

CB: I’m just going to stop there for a mo.

[recording paused]

FDS: Well, you were always busy because you were navigating your entry. Two navigators in effect. They and what you could call broadly a DR navigator and the IT.

CB: So the dead reckoning navigator —

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Is the DR. And the IT is the one using the electronics.

FDS: That’s right.

CB: Ok. So we’ll come to those in a moment.

FDS: We swapped them around a bit.

CB: Right. And on, so on your tour with 196, did you do the full tour or did you then go and do something else?

FDS: No. 196 after about twenty operations 196 for some reason was, well a good reason converted to Halifaxes. Some of it was diverted to Halifaxes. I think Watson with the remainder of that crew, I think they went on to Halifaxes to finish that tour and I flew spare. I flew spare. All sorts of odds and sods. Flight Commander Edmondson was one but as Squadron leader.

CB: But still in, still in Wellingtons you were flying spare.

FDS: I think this was Stirlings.

CB: You —

FDS: That was it. I’m sorry. I’m confusing myself here.

CB: Right. So, just to step back a bit 196 you did twenty ops.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And at the end of your twenty ops what did you switch to?

FDS: Well, I think I was Stirlings.

CB: You did.

FDS: I know I was on —

CB: Never on a Halifax.

FDS: No Halifax.

CB: No. Right.

FDS: The Stirling was a hell of a rotten aircraft, I think.

CB: What was, what was the point of the Stirling?

FDS: It didn’t climb very well. It was electrical more or less throughout so that you could select undercarriage up, and then select undercarriage down and one wheel would come down. So you’d say to the trainee crew, ‘You can find, finds yourself a handle and you can turn that two hundred times, and that will lower the wheel, and if you’re lucky it will lock and show, and do you do that?’ And we said, ‘No, we don’t do that.’ ‘What do you do?’ ‘Well, we select down, one wheel comes down, we select it back up again and then we hit the [laughs] hit the plug hard with the nearest blunt instrument and it comes down.’ They were very heavy too. They couldn’t climb. We took, in the early days did a climbing test around Wales. Not very good. And I went with a squadron leader, I think. Modane Tunnel. We had to go round the taller mountains to get down to the Modane Tunnel.

CB: I’m just going to stop a mo.

[recording paused]

CB: In, in flying with 196 it says that you got to the end of the tour.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Having done twenty nine and a half. What was the half?

FDS: Some idiot’s impression. That is you know —

CB: It was an operation that wasn’t more than a certain number of hours was it?

FDS: I don’t know what the [pause] I never queried.

CB: Right.

FDS: I never queried anything like that.

CB: So, you got to the end of the tour. What happened next?

FDS: Trainee. I was training.

CB: Yes. So you, you were posted to an OTU.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: That was at Chipping Warden.

FDS: There was two instructors per course. You know, ex-ops. And what they were doing we had correctly, we did the rule book instructions, and then what was more useful to them was telling them the contemporary position which was more useful really. So that we, you know you don’t know what to expect if you were fresh off a training course. And the first time I went up I was seeing flashes. I said, ‘What are the flashes?’ You know. Little things like that [laughs] ‘People firing at us,’ they said. I said, ‘Are they near?’ ‘If you’re near you’ll hear it. And if they’re very near you’ll smell it.’ Dead right, yeah. You’re as naïve as that. It’s a great shame. A lot of bumping going on. Of course you suddenly realised there a, later on with Lancasters of course four hundred all going, all briefed for the same trip. So if they followed it literally they were flying up each other’s jacksy nearly I would think.

CB: So at the end of your tour with 196 you went to number 12 OTU at Chipping Warden.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So, there were two. A specialist for each. There were two navigators there doing the instruction. You were one of them. How often did you fly?

FDS: I’m just wondering if the other one was, yes, he must have been. How often? Well, I don’t know. It says it down there.

CB: But I mean in practical terms how often did the —

FDS: Didn’t seem.

CB: Trainee crew have a navigator with them?

FDS: Ah, I see. Well, there was a requisite amount and I can’t remember what it was, it would. Does twenty hours sound sensible?

CB: Was it? Right. Might have been. Yeah.

FDS: It’s —

CB: But, but most of the training you did was on the ground was it of the trainee aircrew at the Operational Training Unit?

FDS: I would think, yes. Yeah.

CB: And if you went on a trip with them you’d be standing next to them.

FDS: Oh yeah. Yeah. Be with them. Yeah.

CB: So, what were your impressions of being an instructor?

FDS: Well, you recognised the essentials of it. And because Command, whoever it is can never be as updated as the people that come off ops. And the advances in tactics and technology of both parties was extreme by about that time. From there on all sorts of technology had been flourished. And Germans showed great courage I thought. And tenacity. I met one or two since, you know. Post war. Very interesting. One chap had over sixty Lancasters to his credit. Six or eight in a night.

CB: Amazing isn’t it?

FDS: Yeah. They were good at it.

CB: So, how, how does the time, how did it at the OTU how long did you stay there normally? Did you know how long you were going to be there?

FDS: You were supposed to be, as it says in the, my CO’s note. You were supposed to be off six months minimum.

CB: Right.

FDS: Generally about a year. Six months to a year.

CB: Right. So, in May ’44 you finished at 12 OTU, and you went to a Heavy Conversion Unit.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And that was 1678.

FDS: That’s at Waterbeach that.

CB: Right.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And what were you flying there?

FDS: Lancasters. Don’t ask me which mark. They played about with Marks 1, 2, and 3 and I never knew which we were on.

CB: Right.

FDS: They were, they were very similar. Very similar.

CB: And because you’d been an OTU then you weren’t coming through as an instructor. You weren’t coming through to the HCU as a student. You were a qualified person so how did you crew up in the HCU?

FDS: I went as an odd man.

CB: All the time or just temporarily?

FDS: As soon as I got there. I wanted to get back on a squadron and have a bit of freedom.

CB: Sure.

FDS: Complete freedom.

CB: So, how long were you, but when you, as an odd man but didn’t you crew up with anybody there?

FDS: I think it may say it. That’s my escape picture, isn’t it?

CB: Yeah. Your escape picture in here.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So at the, what my question is at the HCU. The HCU was the point from which people joined a squadron.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So normally it was a complete crew that would transfer from the HCU —

FDS: Yeah.

CB: To the squadron. So, how did you fit into that?

FDS: They needed a bomb aimer.

CB: Yeah. You were put —

FDS: Bomb aiming.

CB: You did bomb aiming did you?

FDS: I think they wanted a bomb aimer.

CB: Right.

FDS: Because I kept putting down bomb aimer forever more. Yeah.

CB: So, at the HCU you were bomb aiming.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Ok. And what was the aircraft?

FDS: I think by this —

CB: So that was the Lancaster.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: And then you went to a squadron.

FDS: That’s right.

CB: And that was 514.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Ok. So what was the crew like there? Your pilot was Warrant Officer Beaton.

FDS: Yeah, inexperienced but good. He died as Flying Officer Beaton DSO and he thoroughly earned it both times. But he, he and his crew, I’d left, I always leave just before they have an accident. I left and they, I left at the time I’d finished a tour and he went over the day after the war ended to bring back prisoners of war and crashed. Killed the lot. So —

CB: Operation Exodus.

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: Operation Exodus, yes.

FDS: Yeah. Or something like that. So, I was very careful how I trod because I wrote to the, the Air Force itself and said, “What’s the account of this?” They couldn’t account for it. I thought they might say pilot error. They didn’t. And they were quite right. The bodies were all in the back of the aircraft and in practice what should have happened whoever was being loadmaster as they now call the bomb aimer presumably say, ‘You sit there and don’t move a bloody muscle. It doesn’t matter what reason.’ Because you know the inside of a Lanc and if you grab on any bit of it you’re impeding and the, what do you call it when you push forward? When you put the nose down.

CB: When you put the control column down. Yeah.

FDS: What’s the —

CB: So, the elevators. Yeah.

FDS: No. No. No. The trim.

CB: Oh, the trimmer, the trimmer, yeah.

FDS: The trim was full forward.

CB: Oh, was it?

FDS: He was complaining that he’d got some sort of aircraft fault. He was going to make some sort of emergency landing and of course he did that with them all scuttling in a panic. I mean I was sorry for them. They’d been in prison for three or four years or more and they’d perhaps had never flown before. So the right thing to do is to say, ‘You’ve never flown before but this lot have and they’ve done it safely and there’s no enemy fire. Sit where you are and don’t — ’ You would be very conscious of the centre of gravity, and if one went to the rear and the others tried to rescue him.

CB: Do you know where the plane crashed?

FDS: Forward trim.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: And it was forward trimmed. Did a flat spin within about twenty minutes of the take off.

CB: Oh, did it? From Belgium.

FDS: France.

CB: Oh France, was it?

FDS: Just on the edge. They are all buried just out, on the edge of the district where all the riots were happening. The French suburbs. I can’t think of the name of it.

CB: Right.

FDS: It’ll come. But the whole lot, great shame. Captains to privates and an Americans who’d thumbed a lift illegally. Well, improperly rather.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Not illegally.

CB: So, it might have been overloaded anyway.

FDS: Only one.

CB: So, when you were —

FDS: Twenty three.

CB: Pardon?

FDS: Twenty three of them.

CB: In the aircraft. With 514 what are your recollections of flying with that Lancaster squadron?

FDS: I thoroughly enjoyed it. I liked the daylights. Some people didn’t. They preferred the nights. But I preferred the daylights. You could see where you were and what you were doing precisely. Real precision stuff, you know. And they were good.

CB: How accurately did you think you could bomb?

FDS: Well, I’m not bragging. A hundred percent. I could do it. But only because of the kit I had I hasten to add. The kit we had at the end was brilliant, but if you asked me how it worked [laughs] it was modern IT before they’d even dreamed of it I think. The Mark 14 was quite a good sight.

CB: Bombsight. Yes.

FDS: Quite a good bomb sight. You could bomb reasonably accurately with that. There was not an excuse normally for being over about what fifty yards with that I would think. But with the latest stuff you could be spot on. That’s why I’m sure you are. I read these people saying they should be more careful in their bombing, and I think just get up there and give yourself precisely thirty seconds to make a decision because that’s what you’d got. And now we had longer to make a decision. A bit longer, anyway. Yeah.

CB: So, when you were lying down in the front operating the bombsight what’s going through your mind looking down at the flak coming up at you?

FDS: Oh, very little. I didn’t [laughs] I have a convenient mind. I shut off. So it gets familiar. The minute I’m free of direct responsibility but —

CB: But actually you’ve got your eye on the target haven’t you? So —

FDS: Absolutely.

CB: So, you’re not —

FDS: Full marks for that. Absolute concentration. Regardless of anything else. But once it’s done it’s done, that’s it.

CB: And after the bombs have gone then you have to wait for the camera to work.

FDS: Yeah, for flash work. The flash had a nasty habit of exploding once every so often.

CB: In the aeroplane.

FDS: It’s like a bomb going off. A bloody great hole.

CB: Did it happen on your plane?

FDS: Not with the Lanc.

CB: So, you joined 514 in June, just at D-Day.

FDS: When?

CB: You joined 514 Squadron —

FDS: Yeah.

CB: In June 1944.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: So D-Day time.

FDS: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: So that’s why you had a lot of daylight bombing wasn’t it?

FDS: Before, during and after. Yeah.

CB: Yes.

FDS: Got a nice letter from the French. With the [pause] that nice little brigadier general to give the award.

CB: Your Legion of Honour.

FDS: Pardon?

CB: They gave you the Legion of Honour.

FDS: Yeah. They gave it to six Typhoon pilots and me.

CB: Did they?

FDS: Wrote a kind letter. A very nice letter as well from the [pause] whoever was the deputy to the man who was boss then.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: It was a very good letter as we. One of the more thoughtful letters I’ve ever received officially. Very good. I’ve got it somewhere.

Other: They singled you out as —

FDS: Couldn’t single out seven thousand.

Other: No. So it was — yeah.

FDS: They single you out in the sense that they give you a decent personal reply and a decent personal awarding.

CB: On three of your trips with 514 you flew as a gunner, a rear as the rear gunner, two of them.

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: You flew as a rear gunner.

FDS: That may well be.

CB: On a couple of occasions.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: Well, I did all the courses.

CB: Yeah, ok. So when you came to the end of that tour of 514 what happened next?

FDS: Well, I saw my CO because I was going to be posted and I said, ‘I gather I’m being posted. I’d like to, you know, I’d like to go back to my reserved job now if I’m not going to, can I fly anymore?’ And he said, ‘No, I don’t think so. I don’t think so.’ So I said, ‘Well, you’re the boss.’ ‘What are you going to do then?’ I said, ‘I’d like to go back to [unclear] I’m going back to agriculture.’ Which I did.

CB: So, how did it work? You had the conversation with him but how did the mechanism work?

FDS: Ah. Walking along [pause] somebody, who was it? We passed the, what do they call them these days? I don’t know. Further education training officer on the squadron.

CB: Right.

FDS: F&ET I think it was called and they could make recommendations I gather. And he said, ‘What are you doing as you’re moving off?’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t know really. If I could move off I’d go — ’ I said, ‘I’m going back to agriculture anyway.’ He said, ‘What were you doing before?’ I said, ‘Well, I’d been at agricultural college. I’d hope to do a diploma and be decently qualified. It’s no good saying I can do a bit of farming. You can prove that by showing it but to know it you’ve got to do it and I’m out of touch.’ So, he said, ‘What about, what about a graduation? What do — ? ’ I said, ‘First of all I don’t think I could do it, and secondly I don’t know that it would be necessarily a great advantage to be a graduate in it.’ So, I rang up my friend who had been put in other words, he was reserve through health. He was genuine enough. He had graduated through London University, I think. I rang him up. I remember the call very well and I said, ‘The Royal Air Force through the offices of the squadron have decided that I could have a degree course. What do you think?’ He said, ‘What do you think?’ I said , ‘Well, I’d do it if I think it would be of any value, but I can’t see how it would be of direct value to me and it would be three more years.’ I said, ‘I’m already six years behind everybody else. I said, ‘Actually,’ I said, ‘I’m six and a half years ruddy years.’ [laughs] He said, ‘You’ll walk it.’ I said, ‘What makes you say that and he said we’ve kept your brain alive during the war and it hasn’t gone to sleep in the last forty eight. He said , ‘I’d go.’ So that was it. I went to see the F&E. He arranged an interview in London. Oh, they got in touch with the principal of the college I’d been at. Had I any reference? So, I said no, so they referred to the old chap who very gladly backed me up which I thought was very kind. And who else signed it? Anyway, I got a couple of references and I was accepted on the next course where there was the opportunity.

CB: Where was this?

FDS: Durham. I applied for Cambridge actually, taking it that it was near Waterbeach and I knew the area fairly well and guess what? They were full. They were full. Almost as soon as I applied they were full anyway. They were about eighty ninety percent ex-service being fair to the universities and they were very good.

CB: So when was this?

FDS: I got married. All these things happened at once. I left the Air Force. I left the Air Force in ‘45 did I? Or ’46. I got married. I was married when I was still in the Air Force. We were. And I was in charge of MT for a few months. Well, nominally in charge. A flight sergeant found himself suddenly [unclear] [laughs] I said, ‘Who runs this unit? I do so far as you’ll continue. When I leave you can inherit it if you like.’ [laughs] So he ran it. He was very good.

CB: What rank were you at this, at this stage?

FDS: Warrant officer.

CB: Right. So just take —

FDS: Yes. On my first unit, the 196 said you can go, you can go on for commissioning. I said, ‘No. I don’t want to be a tiny fish in a tiny pool.’ And it didn’t seem very, I said, ‘It’s not my career. It’s not my choice.’ When I said I didn’t particularly want to fly, true.

CB: Let’s take a step back.

FDS: Just kill people.

CB: You finished in 514.

FDS: Yeah.

CB: Where did you get posted or did you remain with the transport at Waterbeach?

[pause]

FDS: I wasn’t at, I wasn’t at Waterbeach for transport.

CB: Oh, right. So where, where did you get posted to?

FDS: That unit was Hucknall.

CB: Right.

FDS: Watnall. Watnall. RAF Watnall, W A T N A L L. It was also a Rolls Royce area. Watnall, Hucknall. I was so damned busy leaving the Air Force and getting married and thinking about what I was going to do to earn a living and [laughs] I went out and had a drink one night and there was some youngish blokes I thought at the bar the other end and nobody else. ‘Would you like to have a drink with us?’ So, I said, ‘Yeah. Fine.’ They said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m leaving as soon as I can.’ ‘What are you going to do?’ ‘I said, ‘Well, I don’t know.’ They said, ‘Why don’t you come over for casting. We’re open casting.’ And they were open cast coal mining. He said, ‘There’s a lot of money in it.’ I said, ‘I’d be destroying the countryside.’ ‘No, you wouldn’t. We’ll put it back when we’ve finished.’ I ought to have don’t it really. I’d have had three years of extra income because I had a grant but it wasn’t as you can imagine it wasn’t overly generous.

CB: Where did you meet your wife?

FDS: This must be exceedingly tedious for you.

Other: No. No. It’s very, very interesting.

CB: Where did you meet your wife? She was a WAAF was she?

FDS: As I was driving a lorry across from, at Watnall, it wasn’t Watnall. it was Hucknall was the name of the —

CB: Right.

FDS: Hucknall. The airfield was one side and the sort of flying bit was, the flying bit was one side and the admin the other and I was going from the admin side to the flying side with a lorry. Just for the fun of the thing I think. And going down as I got to the gate guess what? There was a lady coming in on her own, and that was my wife. I saw her and I said, ‘My word, she’s new to the place.’ I knew that because it was a Polish unit.

CB: Oh.

FDS: So, I went to the orderly room and a chap called [unclear] Brown was in charge there and I said, ‘[unclear] you know everything. Who’s the lady who’s just reported in? What section?’ ‘She’s on MT.’ I said, ‘Well, well, well [laughs] We’ll put her on duty the first night she’s there. Make her [unclear] her duties are and I’ll meet her there.’ So, she said —

CB: Never looked back did you?

FDS: Hmmn?

CB: Never looked back.

FDS: I didn’t. She did [laughs] she said, she said, ‘I walked in. There was this flight sergeant who took the details because he was doing the admin. I was sitting there,’ she said, ‘This air crew bloke was sitting there with his feet on the table himself.’ I said. ‘Until you came along who else was there to please, I ask you?’

Other: Charmer.

FDS: There she is. Up there on the brown.

Other: Yeah.

FDS: Framed one.

CB: Lovely.

FDS: When I had some hair.

CB: How long did you have to wait to get out of the RAF after that?

FDS: I don’t know. It didn’t seem awfully long. A few weeks. They did, they did their best for me. I’ll tell you what I was very annoyed about. I did an MT course where I was going to supposedly to pass the time. ‘What would you like to do?’ I said, ‘Well, the flight sergeant is going to run it and I’ll do it nominally and I’m going to learn how to do it. So they posted me up to Blackpool I think it was. Blackpool, Weeton, Weeton. Does that sound right?

Other: Yeah.

FDS: Weeton.

Other: Weedon.

FDS: Hmmn?

Other: Weedon. No. Not Weedon.

FDS: Your question was again, sorry?

CB: Yes. When did you leave?

FDS: When did I leave? I’m thinking of when I left. I’m trying to relate it to courses for the time but I didn’t do the actual course. I did two weeks of the course only. That’ll be recorded. I’d been driving for years on farms. With, you know pushing hay suites and stuff.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: So I could drive and [pause] yeah.

CB: And the course was running the MT section, wasn’t it?

FDS: I did, yeah. I did about two weeks there, and the, whoever was dealing with the admin said, ‘There are four Crossley lorries to go down with four thousand pound bombs on, down to Newmarket and it will just take up the timing, you won’t have the tedium of doing the course.’ I said, ‘Well, thank you very much.’ ‘And you are in charge of it.’ And I said, ‘What bombs are they?’ ‘Four thousand pounders, but they’re empty. They’re taking them down to get them filled.’ But we had outriders with red flags and these old, you know Crossley lorries with —

Other: Yeah.

CB: Canvas roof.

FDS: Left hand drive. So, I drove my Crossley lorry. The roads cleared. The Americans would get out our way. Saw the red flags. These lorries. Took us two days to get down from Blackpool to Newmarket where I left. I don’t know what happened to the lorries. I’d done my job. Over to you. That was the last I saw of active service. I left.. Oh, I can’t remember when I left. January. Must have been January. We were married in January, weren’t we? No. We were married. Still in the Air Force. Yeah. I was still in the Air Force then.

CB: You said you were married in 1945.

FDS: Yeah. I thought. Yeah.

CB: It was fairly quick.

FDS: Oh, November to, it was from I do remember that it was from November to January. Yeah.

CB: So then you did your agricultural college at Durham. What did you do after that?

FDS: University of Durham.

CB: Durham University.

FDS: They haven’t got a farm there. They did useful stuff from my point of view. Because I was familiar with the kit then and it changed. In the same way that the Air Force changed its technology so did agriculture.

CB: How long was the agricultural course at Durham University?

FDS: Three years. And if you did an honours degree it was four.

CB: Right.

FDS: So I went to see the boss and said, ‘What do I do now? I’m seeking advice.’ He said, ‘Well, you’ve a choice. You can do an honours degree but agricultural colleges are being offered to counties and they haven’t got them established so you could get in on the ground floor if you wish. ‘But,’ he said, you know, ‘I’d back you for either.’ So I backed for three jobs. The agricultural Co-op in London, and Hartbury had just, Jack Griffiths had just bought Hartbury on behalf of the Authority. So I was one of the first as lecturer agriculture. Then became vice principal there for about thirteen years. And then I did vice principal up in Staffordshire, Penkridge.

CB: And you retired from there, did you?

FDS: I retired from there. Oh, and then [laughs] I was invited to sit on the panel for whatever it was called when they allowed farmers so much milk, you know. Milk quota. The Milk Quota Panel. Would I sit on the Milk Quota Panel for Gloucestershire? I said, ‘No. I’ll do it for any other county if you wish but not Gloucester. I’m not going to quota people I know.’ So I was quoting, quoting still people I knew in Wiltshire. Just funny really. Strange.

CB: So what brought you to Gloucester?

FDS: Hmm?

CB: What brought you here to Gloucester?

FDS: The job. The fact that I knew it. I didn’t know Gloucester. I knew of Gloucester, and I knew of Gloucestershire but I didn’t know it at all really.

CB: And at what age did you retire?

FDS: Whisper it quietly, sixty two. I was going to retire at sixty. You could retire at sixty and I had enough bottling about one way or another. I didn’t take, I didn’t think I could subject my wife to dotting about. You can see from that I was dotting about, you know.

CB: Yes. Yeah.

FDS: All the time.

CB: Yeah. How many children have you got?

FDS: There was three jobs so I went for this one and got it. It had accommodation. A clapped out cottage on the side of the main road where you turned left to go in to Hartbury. So they said just wanted to let you know. So they then put me in the corner house of the college and a very busy old lady, the butler’s wife came across. She said, ‘Captain Canning, and Captain Ramsey were there.’ I said, ‘I know but it’s been disinfected since they were there.’ They were there on, you know during the war.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: He was still there post war.

CB: Was he?

FDS: A pathetic old man. And he got married to quite a nice lady and they said she’s having a baby. I said, ‘Good. Well done.’ And it was a girl. So that was the end of George Canning, Prime Minister and foreign minister and aspiring gauleiter of the south west. He would have been.

Other: Did he go to Australia?

FDS: No.

Other: No.

FDS: Why did I say Australia?

Other: No. I was asking that.

FDS: I was in Australia.

Other: No. No. Canning.

FDS: Oh, that Canning.

Other: Yeah.

FDS: Canning was in charge of [pause] he was in charge was he? George Canning was foreign minister.

Other: Right.

FDS: Way back.

CB: How many children did you have?

FDS: Two. I’ve four grandchildren and six great grandchildren. Only one grand-daughter. Don’t put down regrettably because the others might read that [laughs]

CB: Right.

FDS: You never know anyway.

CB: Finally, what would you say was the most memorable point of the war for you?

FDS: Meeting my wife. It was.

CB: What was the —

FDS: Memorable of the actual war [pause] I think the second tour. And I would say particularly in daylight. I don’t know if she, I don’t think it should be recorded because I, I had an understanding with my superiors of 514 that we could please ourselves, Weeton and I, within reason. So that if for some reason you didn’t have a primary.

CB: Yeah.

FDS: You could go and do a secondary.

CB: Sure.