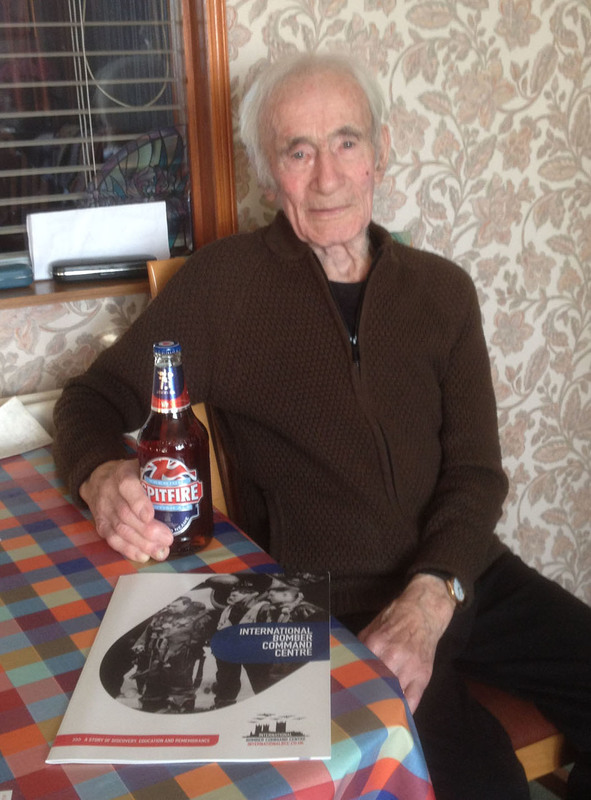

Interview with Frank Wilcox

Title

Interview with Frank Wilcox

Description

Frank Wilcox was born in Wales and worked in aircraft manufacturing. He was later called up and served in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry. He was taken prisoner at Anzio and became a prisoner of war. When he was released and returned to the UK via Ukraine he returned to work for the same factory – this time making refrigerators.

Creator

Date

2016-12-01

Coverage

Language

Type

Format

01:21:31 audio recording

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AWilcoxF161201

Transcription

CB: This particular interview is different from the others because it’s based on the fact that in the RAF all aircrew were at least a sergeant.

FW: Yeah.

CB: Whereas in the other forces people started and fought in various other ranks as well.

FW: Other levels there were. Other levels there were.

CB: So today, my name is Chris Brockbank and today we are in Oxford and it’s the 1st of December 2016 and we’re with Frank Wilcox who was in the army and then became a prisoner of war. And it’s the prisoner of war part that is particularly important.

FW: Yeah.

CB: In this interview. So Frank what are your — where were you born and what are the original, what are the earliest recollections of life?

FW: I was born. I was born at Blaengarw in, I’ve said the date well I went to school, you know. Dad wanted the bigger school because we moved when I was ten years of age like to Oxford. 1930s. 1935. Yeah. I’d say 1935 to Oxford. What it was like — my two brothers, older than me, they came to Oxford. Got a job in the pressed steel and lived with my auntie in Florence Park. And so they said, ‘Why don’t we come up?’ So my, so my dad said. ‘May as well.’ So we all just moved up there. Later on my two other brother who had left there. They moved up as well. In the October. So the whole family moved up to Oxford in the end. There was nobody left down there.

CB: But where did you go to school?

FW: Well, went in Blaengarw boys. It was the infants school in Blaengarw till I was ten. Then of course the other one, Oxford we went to Temple Cowley School in Oxford until I was fourteen.

CB: Right.

FW: Then of course I went to work then. Pressed steel.

CB: And what did you do in pressed steel?

FW: Well, when the war came they were building fuselages for aircraft and I was underneath. They put the rivets in. I had to make sure the dolly thing was in the hole so when they put the rivets down on to it. It was a cushy little job really for a while. And then was a damned fool. My mate was working in the paint shop persuaded me to go down with him. If I hadn’t gone there I wouldn’t have gone in the army at all you know. But the bloke that was with me. Same age as me. He was still never went in to the army. If I’d have stayed there I would never have gone then in the flipping army.

CB: Because it was a reserved occupation.

FW: Yeah. Aircraft see. And of course a big mistake.

CB: So how did you like that job?

FW: It was alright. Yeah. Ok yeah. I was fourteen then. Only had about eighteen months and then a colleague persuaded me to go down with him and of course that was a big mistake wasn’t it? In the paint shop. Had to go and see what that was. Nothing there. So when I was eighteen I was called up. 18th of March 1943. Started out at Colchester. Yeah.

CB: So you were, you were called up in Oxford.

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: And what did they do when they called you up?

FW: Well I mean you had to go down and get a physical you know, down in the town hall and all that and they said they’d let me know. And of course that was in the February I should imagine because then by the March they called me up. 18th of March I was at Colchester.

CB: They sent you to Colchester.

FW: Then six weeks in one part of the barrack what you called, you know light training and all that. And they were with the what’s-the regiment. What do you call them? Heavy, heavy, the slow, the slower ones you know. Marching.

CB: The ones that do slow marching.

FW: Marching slower [unclear] Then after six weeks, yeah that’s where I started. [unclear] was on about the Oxford Bucks they were about a hundred and forty eight a minute, they were.

CB: Yeah.

FW: They were what they called the light infantry.

CB: Yeah. Well the infantry always marched faster.

FW: Marvel. Ooh.

CB: Yeah —

FW: Then another ten weeks there. Then we moved to near Aylesbury where the Oxford Bucks. Second Bucks battalion was there. Stayed there, and then after — probably about October time we moved to Dover. Of course bloody Dover you find the Germans were firing almost the big guns over every so often weren’t they? Landing In Dover they were. Had to be careful what you were doing down there.

CB: So when the shells came over?

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: What did, what were —

FW: Well you didn’t know where they’d land anyway see. There was no specific place for them to land. They didn’t land on our barrack mind you. I admit that. We were right, right at the back. Right at the back of the town you know.

CB: What were the barracks called?

FW: Old Park. Funny thing was they were new barracks but Old Park Barracks they were called but they were very new barracks actually. Yeah.

CB: They were on the reverse side of the hill were they?

FW: On the top. They were out of the tunnel they were over the top like. They were out sight. You couldn’t see them from the road. Not from the sea side.

CB: And what did you do there? What was your, what was your —?

FW: We just training we were doing more or less.

CB: What sort of training were you doing?

FW: Well. Like marching most of the bloody time. But anyway I was there for about — just before Christmas ‘43 and then I was I don’t know a few of us had to be transferred to, I don’t know — a half a dozen or more. A dozen probably. So many people out of each battalion. You know. Out of a company like. Happen to be the worst of the. So you had to go from there to Liverpool and we sailed right then from Liverpool to Italy. Naples.

CB: This was with the Bucks regiment was it?

FW: No. No. No. I wasn’t with them. No. No. No. Not there. I’d left them.

CB: So when you went to Aylesbury. You were in the —

FW: Yeah. I was with the Bucks then.

CB: You were in the Bucks regiment.

FW: And then we went to Dover still with them. But when I went abroad I weren’t with them then. I just [unclear] it was back Oxford Bucks again.

CB: Right. But you were still in the infantry.

FW: Infantry. Yeah.

CB: Yeah. Ok. Oxford and Bucks.

FW: Ox and Bucks.

CB: So when you went to Liverpool then what?

FW: Well we sailed then from I don’t know started about, January, June, January to Italy. I mean we never knew where we were going. No one told us where we were going like, you know. We didn’t know where we were going.

CB: Right.

FW: We had to land up in Naples.

CB: Oh right.

FW: The harbour had been bombed badly like, you know. And then we had to walk about three kilometres or more to Mount Vesuvius you know, the [unclear], where the volcano was. And we unpacked near the ruddy slope. And we had tents then, you know them bell tent things you know. The round ones.

CB: Yeah.

FW: We had loads of them there in there, for about a month. Six, five weeks and then of course they couldn’t get through. You see, what it was they couldn’t get through Casino.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Monte Casino. They couldn’t get through so all of a sudden Anzio was there, they landed at Anzio. With the Americans, you know, we were with Americans attached to the American 5th Army we were. Montgomery was on the Adriatic side like you know. At the right hand side of Italy. We were on the left hand side with the American 5th Army. ‘Course we didn’t see Americans then. We were mostly British troops we were with. But we landed in Anzio and took over from the regiment. But later. At ten o’clock at night, I know it was late. 15th of June, February. That was nineteen forty —

CB: ‘44.

FW: ’44. Yeah. Then of course the next day, a Wednesday it was quiet. We were on a slope like that you know. Big slope.

CB: Steep slope.

FW: And we had the machine on a tripod like you know. Had the shakes. Anyway, nothing happened. The next morning about up to Thursday, that would be the 16th 17th probably and something was coming. I looked around. There was a load of troops on the top. Looked dressed like American helmets, looked like the German helmets from the distance in the dawn you know. They were. They were German paratroopers weren’t they? And of course before we could turn around he said to me ‘I’ve got the machine gun,’ the Bren, he said, ‘I’ll take over now,’ he said. I said, ‘Ok.’ You know, less than five minutes later that man was dead. Shot. Landed on top of me. I’d never seen anybody dead before. He landed on top of me. I’m covered in blood and before I could turn around there was a bloody German with a bloody Schmeisser and there’s me with a Tommy gun. I thought Christ. This is it. ‘Raus. Raus.’ So what he meant by bloody, ‘Raus.’ I got up anyway. And from then for four hours we carried German wounded back and forth. Behind their lines we were. Four ruddy hours doing that. I’ve never seen so many dead bodies in all my life. They were piled up like bricks they were. They weren’t ours. They were German troops they were. Not ours. [unclear] not behind their lines obviously. I’d never seen so many dead people. I’d never seen anybody dead before.

CB: So how did they pile them up then? Just —

FW: I don’t know. They were just —

CB: Literally.

FW: Yeah. Like you were lying on the floor like that, like that, like that. And they would put another one on top of the other.

CB: And they did.

FW: One on top of the others you, like, you got four high.

CB: Then what did they do with them?

FW: Oh I don’t know. I don’t know. Then after that we were there for four hours. We went back down into a, down to a gully somewhere, you know. We stayed there for a while and they moved us on. We landed up in Rome then. In a film studio of all bloody places. There was a film studio but of course they had to clear out a big place like that and the toilets were [laughs] the toilets were outside and doing anything — and at night time they had big fifty gallon drums in there. Two had to go in there and do what they had to do, you know. You had a platform for going in there like you know. Standing there, going to have a wee or whatever you had to do. And then from then on we —

CB: This is in Rome is it?

FW: In Rome that was. Yeah.

CB: Right.

FW: In Rome that was. Yeah. That was all Roman. Didn’t see much of it, I admit and we’d been there a couple of weeks I think and then they moved us on to some lorry. On to a railway station. They moved us up higher into Italy. A place called — I can’t remember the name it was called. And it was a prisoner of war camp for British prisoners who were captured in the desert. I think they were. And we were there, you know, for about a month. And we had no bed at all. We lay on straw. We didn’t have a bed. We were inside you know. We weren’t outside. We were inside lying on bloody straw really we were. Then we were there a while and then we [pause] what did we do after that? Yeah and then after that we were on the train again. We were right through Italy. Through the Brenner Pass into Austria. Merseburg. Into a camp called Stalag something. I remember the one at the end but I can’t remember the first name of it. It was a biggish camp. And we were there for a month. And they moved us back then to where we were now. Stalag Luft 3. Next to the RAF place, you know. Next to us. Then of course then we —

CB: That’s in, that’s in Poland.

FW: Yeah. That was in Poland now.

CB: Stalag Luft 3.

FW: Yeah. It is Poland now but it was Germany then. East Germany then. Yeah. Yeah. And then what did I do. Well then I went to a working camp. They called it a 40 30 working camp. It was —

CB: So you came out of Stalag Luft 3.

FW: Yeah. Into a working camp.

CB: Into — what was the other one called?

FW: Stalag. 4030. That’s all I knew. 4030. And it was three different factories. One had four hundred. One had three hundred working with you. And the fifty with you in the factory making drainage pipes. Orderly came in. He came in. You know the old, you know the coal, [unclear] kind of thing, you know. We had to empty them out for the — do their kilns like you know, and then when they done the kilns we used to drop them down, brick it up for about thirty six hours and then knock it down and then they bring all the pipes up. We had to stack the pipes in these, in these, they caught it in the railway track that the coal had been in, in the first place. Put straw on the floor, you know and pipes on top. Line them all up. Till the carriage was filled right up. And that was it then.

CB: What were the pipes made of?

FW: Well the drainage pipes were ordinary drainage pipes. Yeah.

CB: Were they?

FW: They were like done up the top you know with the, how they done them. They dropped them down into the kiln and then line all one side and then the other side and down the middle. And then they’d brick it all up and light it for about thirty six hours or two days you know to warm it all up. Then it was cooled down for twelve hours. Enough to thin down for four or five of the kilns inside there. So you wouldn’t light just one. But we didn’t do that. We just, we were just unloading the thing and putting them back. We were putting the pipes in the railway carriage like, we were. Then but that was on till like about, that was November time. Could be December maybe. I don’t. For some reason I had a poisoned leg or something. I don’t know what it was. I don’t know what. They couldn’t treat me there so they sent me back to the main camp.

CB: A poisoned?

FW: Stalag Luft 3 again.

CB: What? Sorry. A poisoned what did you say?

FW: I had a sort of poisoned leg or something.

CB: Oh a poisoned leg. Right ok.

FW: Swollen up like, you know.

CB: Ok.

FW: And they sent me back to the main camp again. Of course I never saw any of the blokes again. Because time, time came through and the Russians broke through in the January. We were still in that camp you see. Our lot had to march back to West Germany, they did. I did see one of my mates then after the war. He came from Birmingham. I met him afterwards. We met. A lot of them died of cold. It was cold see in 1944/45. It was very cold I can tell you.

CB: It was a very cold winter.

FW: And then anyway we moved. I met up with an Irishman, naturally. We got bloody lost. We were going, there was two roads like that. We went messing about. They, when we looked they vanished. So we went up that road. We were on the wrong road weren’t we? They went the other road. So we landed up back with the Russian soldiers. They didn’t know what to make of us to be honest. Not really. The only way we got away with it was one of the coloured blokes there in the army you know, Indian I think he was. He more or less realised them that we weren’t bloody Germans. So he sort of passed us off like you know. Anyway, and for two weeks we were out on our own we found a horse and cart, bed cart. And we met up with two, other RAF blokes which weren’t, they weren’t officers. I don’t know what they were. How they got to be, how they got there I don’t know. I couldn’t tell you. They weren’t, they weren’t like officers. Not like that. They were only —

CB: NCOs. Were they NCOs?

FW: One was a sergeants. And one a private or something. Sergeants I think, or something like that.

CB: Yes.

FW: And we were only there for a couple of weeks all everything was empty. You go over and over. Nobody in them. The only thing we find was whether they were booby traps or not, you know, like. But other than that you could do what you liked. Picked anything. Shops. Take what you like. No one would stop you. Anyway, we picked out where we should have gone in the first place with this big, it wasn’t a castle but some very big place you know. And we got there eventually. Then we was there a little while, then we transported like. This is as very far as we got the train, cattle wagons you know. And the only fire is it’s a long train aye. We didn’t realise they were bloody coal wagons behind us. We didn’t know that. And any way we was in here, and all of a sudden after we’d been gone awhile because it’s winter time now. Snow’s on the ground like that. All of a sudden I looked out and the bloody carts were all piled on top of one another. So what had happened someone had uncoupled the train. The train went forward. The train went down the grade slightly. That was going down. They were coming back. Of course we didn’t know that wasn’t it? We hadn’t jumped out we would all have been bloody caught there in that train, the carriage. They followed me out. The five of us. And three or four were killed in that accident. And then we had to wait then.

CB: What sort, what sort of speeds were the trains going then?

FW: Well they can’t. I don’t know. I mean they were backing back and he was running down gently like, you know.

CB: Oh right.

FW: Of course obviously they rolled on top of each other didn’t they?

CB: Right. Yeah.

FW: About four or five carriages were all crushed weren’t they? All the other blokes were lucky to get out. About four of them were killed I think.

CB: So were you in a carriage or in a wagon?

FW: Oh in the wagon. Oh Yeah. Yeah. Like a railway wagon. You know. But we had to wait then for the next train to go to Krakov then. We waited the next train to come through. Course when it came through it were bloody full up weren’t it? With thirty to a carriage weren’t it. And then of course that went on for, right across. I mean then we just went on to, to where we supposed to go to. To, I don’t know Ukraine or whatever you know. But the trouble is, you had to. The toilet, you know the toilet you had to do it on the railway line. And believe me that wasn’t pleasant.

CB: But this is all in an area under Russian control is it?

FW: Oh that was. Yeah. Oh that was. Bloody Russians had already passed us. They’d gone all the way in Germany already they were. That was going for a couple of weeks later that was. And then we were in a place and luckily for me I was really bad by then. And luckily for us a hospital ship came. The Duchess of Richmond hospital ship. We landed on, we passed on there, we went through the Black Sea and through the Dardanelles and into the Mediterranean and stopped in Gibraltar.

CB: But how did you get on to the boat that took you that way?

FW: Well, I was bored up to a point. I was in a hospital bed all the time I was on that boat I was. A hospital bed. And then in Gibraltar somebody came on giving us stuff. You know piling different things from Gibraltar I don’t know. We landed in Greenock, Scotland in the end anyway.

CB: Oh.

FW: So.

CB: So when?

FW: I was there about six weeks.

CB: When did you get back?

FW: That was. What would it be now? That must be now ’44. I don’t know. The war was nearly over by then I think, I’m not sure. About August time I should think. Mid July, August time something like that, 45.

CB: Oh the war was over by then.

FW: The European. Yeah.

CB: in Europe. Yeah.

FW: I think by then. Near enough over then. No. The Japanese war wasn’t over.

CB: Right.

FW: But it still out there mind you.

CB: Right.

FW: Anyway, I came home for a week and then I had to go up to London. Richmond Park. For about six weeks I suppose. And then you transfer down to Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire.

CB: What did, what did you do in Richmond Park?

FW: Nothing. Just doing training like. Physical training and different things. Didn’t do much at all really. Went down to Aylesbury. That part of me didn’t realised it was, what do they call it, moving camp for getting out of the army like. Then we had about a week and we went up to London. I was disarmed you know. Given civvy clothes and that was the end of it.

CB: Were you carrying a rifle all this time?

FW: No. No. No.

CB: Right.

FW: No. Never had a rifle after that. I never had a rifle after that. I lost my rifle out there. But no it was alright in the end I suppose. But I wasn’t well, I was bad from when I got here. I was still bad mind you.

CB: What was this infection in your —

FW: Stomach. When I think about when I was in that hospital in Glasgow, Greenock there was a bloke next, next to bloke and me he had an ulcer and it burst you know, and all of a sudden I’ve never seen such a [unclear] bloke in all my life. I thought Christ. I thought, I’d be in trouble. I couldn’t have had an ulcer. Couldn’t have been an ulcer. It was something. It wasn’t an ulcer. It couldn’t have been.

CB: What happened to him, when it, when it burst?

FW: I don’t think he died. It burst. But he didn’t die, I don’t think.

CB: No.

FW: No, no, no. I don’t know.

CB: How could you tell it had burst?

FW: Well all this in the corner of his mouth. It was everywhere, you know. So I didn’t, I don’t really know what happened. I don’t think he died. I don’t think so anyway. I’m not sure but I mean don’t know. But I didn’t know him anyway. I didn’t really know him. Then and after a couple of weeks had passed went home for a week and then up to Richmond Park then. Then there about six weeks there and then up to Aylesbury. Demobbed sort of by the October ’45. And that was it. Nothing special.

CB: Then what did you do?

FW: Well I went home for a while and then back to pressed steel then. On the fridges.

CB: So you came back to Oxford? Yeah.

FW: Making refrigerators they were then.

CB: Oh. Right.

FW: Back there then. Yeah. Then after a while I got fed up with that. I wasn’t very. I couldn’t settle like you know. Then I went down. I could drive up to a point and then I went down. At the time they, all petrol companies all pooled petrol they used to call it. It was in all the lorries then. It was a sort of a grey colour like you know. It said pool on it. But then after the war they all went back to their like. I worked for the Anglo American Oil Company. Esso. Anyway, a different company. They all went back to their original company. Well I could drive up to a point. My. When I was with the old boy, he said, have a go. Have a go on a lorry boy. I passed my test anyway and it was alright so had a lorry of my own then. And had a bit of a dust up with the manager and I went on British Road Services for about six years. Then landed back in pressed steel again. That’s where I met my wife.

CB: In pressed steel or on the lorries.

FW: After five years I went and left them, British Road, national you know left them. Went back to the pressed steel crimp shop.

CB: Right.

FW: She was making the thing and I was putting them the cars. So that’s where we met. Up there.

CB: What was Doris doing?

FW: She was doing the things that should have gone on the cars, know them, down the back fenders, you know the fenders? Behind them you usually put a cover on them like you know, like that, she was making them. But we were putting them on. On the little trolley we were sitting on there. Putting the screws in and going on, line was still going. We were sat on a little trolley rolling around. Yeah. And then of course the next year, we got married the next year.

CB: So that was forty —

FW: 1955 that was. ‘55/56.

CB: ‘56

FW: ’56 when we got.

CB: Right.

FW: Yeah.

CB: So you met her in ’55.

FW: Yeah. Yeah

CB: And married her —

FW: Well hadn’t gone out together by then. Not till ’56 really. You were about a year old —

PC: That’s right. I was born in.

FW: When we went up to. Lived in Worcester then. Eddie lived, lived in Worcester. Been up there in the first time we met her didn’t we. Paula was about a year old. Yeah. And then, anyway, worst part of it was my mum, she’d been bad for a while actually. She was in the hospital. She had pernicious anaemia you know. And she had to be taken to have some [unclear] injection for quite a long time. Anyway, visiting time was from half seven till eight. I was a bit late then. I was a quarter to eight I went in there. My two brothers were there. Do you know my mother must have waited for me to come back. She died right in front of me.

CB: And you were the last of ten children?

FW: Yeah. Yeah. And she died right in front of me.

CB: Good Heavens.

FW: And all the lines on her face disappeared you know.

CB: Did they really.

FW: I couldn’t believe it, and my two brothers. The oldest brother were Jack, then my other brother Tommy were there. ‘She must have waited for you, they said.

CB: Yeah.

FW: She must have, must have. And she really. My mother had a hard life because, she was, she was the oldest of her family you know. And she had shoes at thirteen in a farm. Of course all them children you know. Ten bloody children after that you know. Too much really. The only thing I can say my father worked, and had no handouts. You know he were never on the dole or anything like that. There was never a lot of money. We didn’t have a lot of money in those day. If you had a pound you were lucky. Thirty bob you were lucky. So we never had no, never had any help from anybody. Only what anybody earned. And of course as the boys got older they wanted to go to work in the mines with him like you know. All of them. But of course they all got fed up with the mines. They ran away and that’s how we landed up in Oxford. And the best thing we ever done that were. They said to my mother, ‘Would you like it up there, mother?’ ‘Anyplace is better than this. This is like hell,’ she said. You had four coal mines. Three in the, where we live, and just below where we lived we had another bloody coal mine. And on the back we had a big mountain all around us you know. You couldn’t get out. You was back all the way around you know. You couldn’t get out. And on the top of the mountain you had a big area. You come from there. They’re tipping all this on top of the mountains, bloody stuff. They were just tipping this stuff behind our house in the end, you were right around the back of our house. It was over thirty foot high it was.

CB: Is this the. Is that the —

FW: And all the dust. You couldn’t wash her washing it was, the wind was blowing this way.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Couldn’t do any washing, the coal was blown off the, off damned tips.

CB: And was this storing the coal or was that the spoil?

FW: No that was the rubbish that was.

CB: That was the spoil?

FW: Bits of coal in amongst it like you know obviously.

CB: Yeah. Yeah.

FW: But that was just the earth.

CB: Just the rubbish.

FW: Supposed to be. Had lots of little bits. The kids used to go round with a little bag picking all the bits of coal up like you know, and sell that if you could. But if the wind was blowing that way you couldn’t do any washing. Any coal dust was blowing off see. Oh she had a hard life my mother but you never hear her complain.

CB: Right.

FW: No. No.

CB: But Oxford came to the rescue?

FW: Did yeah. She said anything’s got to be better where we live here. Because she came from the country you see.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Place they call Kerry near Newtown. In Montgomery. Well it’s not Montgomery, now they changed. They changed the county from twelve to about seven I think they did. And then they amalgamated two counties into one like you know. Give it a different name. It’s now just called Montgomery. The town of Montgomery is still there but not the county.

CB: Right.

FW: Funny part of it. The Irish name Kerry. Where she lives. A village called Kerry. I went up there once. Nice little place up there.

CB: So in Oxford you settled down. Where did, where did you live when you were married?

FW: Oh yeah. Yeah. Well we were that was a problem. I say my mother died. And Dot and I moved in with my father like you know. I mean it was really going well. The trouble my brother. Older than me. He was living with Mary’s brother, and he had no children, and Mary was expecting a baby and they said we’ll have no children here. So they had to get out, and craftily he worked, he worked around. Made trouble for us didn’t he? He got us out and he got in. So in the end then we had to buy a place of our own didn’t we. In Kidlington.

CB: In Kidlington was it?

FW: In Kidlington. Yeah.

CB: How long did you stay there?

FW: About two years, and then we moved down here and we’ve been in this place here nearly fifty seven years.

CB: Have you really.

FW: 1959 we moved in here. Yeah. Weren’t it. Hard to believe the bloke next door he’s, I think he’s Chinese I think. He was on about how much did you pay for the house. What do you think? They’re going for around three hundred thousand now you see around here. And he said, ‘Oh a hundred thousand?’ No. No. No. ‘Fifty.’ No. No. No. Forty? No, No. Going down and down. In the end. ‘How much did you pay then?’ Two thousand five hundred and fifty. This one, this one here was fifty pound dearer than there because we had got two rooms. There next door’s they’re rooms right through like you know.

CB: Right. Right.

FW: He said, yeah. I said what everybody’s got to realise the wages was only about eight or nine pounds a week sometimes. So it really worked out exactly the same like you know.

PC: Same. Yeah.

FW: The wages weren’t like heavy big wages. I’m telling you. I was lucky really in the in the end when I went back to pressed steel. And I recall the P6 Rover. It was a lovely car though. And we worked on them I was pretty good. Gave me forty odd pound a week I was earning. They were only getting about sixteen if you were lucky. Everybody other. So I done pretty well really for about. I was on there for about eleven years on there.

CB: So when you went back to pressed steel what were you doing then?

FW: Well that was the first time as I told you we was on the trim shop were there. Then the Suez crisis came up in 1956.

CB: Yeah.

FW: And then we had we had to move. I had to move from there back into Morris’s.

CB: Right.

FW: So in the end, when it cleared up I went back to the pressed steel again then. So that’s how I ended up on that Rover side pretty well. Pretty lucky really.

CB: So what age did you retire?

FW: When I finished I was on forklift driving on the end. In the end I was sixty three and a half then. And I worked out if I stayed until I was sixty five it wouldn’t have been any more anyway. I might as well go now. So that was 1988. 1988. I was about sixty three then. And that was it. I had a little joy. I had a spare job up there. And the cars, the pressed, the pressed steel side for a couple of years and I packed that in and I haven’t worked since. Yeah. We’ve done alright because do a lot of caravanning. We had three different caravans different times. Remember the first one and then the bit bigger one and then the really big one we had in the end. A big one. That’s why the hedge is so high. To put the caravan behind that way so you couldn’t see the caravan from the hedge. It was a lot higher back then but still higher now than the hedges.

CB: But the children liked the caravan?

FW: Oh yeah, yeah. Sue. Oh how old was she?

CB: How many children did you have?

FW: Two. Two. And she was only about a year and a half old wasn’t she when we had our caravan?

PC: Something like that.

FW: Oh they all loved the caravan. Oh Yeah.

PC: I don’t remember to be honest. It’s been a little while.

FW: We had her for, had them for ten or twelve years all the different caravans, more than that. Went around different places. All around. I went to Blackpool once with it but most of the time I went down the south of England like, you know. Bournemouth and down that area mostly. Weymouth. That type of place. Yeah.

CB: Going back to your time in the prison camp. How big was the camp? How many people were there?

FW: Do you mean the working camp?

CB: Yeah. The working camp.

FW: I would say there were four hundred in one factory. Three hundred in another. That was seven hundred. And we were a hundred and fifty. We were fifty. We were a small factory. We were small. And at night time you know what they done? You had to take your shoes off and your belt. So you couldn’t bloody escape, run with no shoes and no belt. But other than that I got to be honest as the German soldier themselves I had no problem. They weren’t like, like doing any harm to us. Weren’t doing any harm to us. I can’t say they did.

CB: What — what —?

FW: The only ones you’d got to watch were every so often these blokes that came round with these black suits, you know. Gestapo. Anyway they were the ones to watch, I’ll tell you.

CB: So did the, did the Gestapo in to come in to the camp?

FW: Yeah.

CB: Much?

FW: They used to roam around yeah. But they. You know, I mean the ground weren’t all that big. There were seven hundred of us there you see. Seven hundred and fifty people there altogether. Four and three and fifty. Wasn’t a lot of room around then, move around. And we had the Red Cross parcels, you know, coming in and all the names were different where they’ve come from, like you know. Bristol, Brighton or could be London or anywhere like you know, and each one more or less the same ever time like, you know So all we done me and my mate we shared the two together you know. He had his and I had mine. But we had them for every fortnight then. But then it got to every month. And in the end we never got them at all in the end. And at the end of the war you didn’t get any.

CB: What was, what was the, what were the components of the Red Cross parcel.

FW: Little bits of tea, packets of tea, and cocoa, and biscuits and different things like that. Packets of cigarettes. Cigarettes didn’t they. You see people who didn’t to smoke used to sell it. Sell the cigarettes to get more food like, you know. I smoked a little. I wasn’t a heavy smoker. I used to smoke a bit but not a lot. But no, I was going to say I didn’t have any problem with the German soldiers themselves. No. I didn’t.

CB: What were the Gestapo looking for?

FW: You had to be careful like that. You didn’t know what they were up to half the time. They were always tall, you know, and black. Bloody black suits they had on. But the Germans soldiers themselves were no [unclear], same as we were. They didn’t bother. They were alright. Yeah.

CB: So what was a working day? What time did you get up?

FW: Normally I got up early. Was up 7 o’clock in the morning. Oh yeah. Got back about four or five. Quite a few hours. You had a break like you know, like at dinnertime.

CB: In the factory?

FW: Yeah. In the factory. They had a little room in there. Yeah. Yeah.

CB: So what did you —?

FW: They didn’t give us any food. What we took with us like. You know. A sandwich or something if we had any bloody bread left ever.

CB: How were you fed in the prison camp? You started off with breakfast. Did you get breakfast?

FW: Well a lot of it was food I didn’t like much anyway. If it wasn’t for the Red Cross parcels I think we would have been in big trouble. You would have been. Sure we would have been.

CB: What did you have for breakfast?

FW: Well whatever it was if you were bloody lucky. Maybe a cup of tea. Maybe. That was about all. A bit of a slice of bread perhaps. That was about all. Nothing else. You had, they gave you like a lot of sauerkraut and all that sort of thing you know. That sauerkraut. I could eat it. I had to eat it up to a point but I didn’t like it. I had to eat something. But basically it wasn’t too bad. At the end of November, December we went back to the main camp and that was the end of it. Only the one I saw again when he came to Oxford to visit. Old Bert. Yeah, he came. Last time he came. He came from Birmingham. Solihull he came from somewhere. He came down and stayed for a couple of nights. And then a lot was happening and we lost contact from there then.

CB: Had you met him in the prison camp or did you know him before?

FW: No. No. No. Never met him before. He was in a different regiment from me. He wasn’t in our battalion. He wasn’t in the Oxford and Bucks. He was, you know [pause] I don’t know what he was. British army somewhere but I don’t know what. The point was the blokes that went to Anzio, if he had done what he should have done we would never have had half this trouble. He went there. There was hardly anybody there. No opposition at all.

CB: When you landed.

FW: Landed. No opposition. But he stood there a fortnight see. Messing about. Instead of moving in. Bringing troops in of course by the time he waited the Germans reinforcements come in didn’t they? If he’d have bloody done what he should have done what he should have done probably none of this would have happened. See Rome was only about [pause] well in kilometres about thirty kilometres away. Rome was. From where we were at Anzio.

PC: I think.

FW: But of course I mean. How do you get there is the problem.

CB: So who was carrying the machine gun when you landed?

FW: What it actually —

CB: It was a Bren gun was it?

FW: A Bren gun. Yeah.

CB: Right.

FW: Actually the Bren gun was there when we. They dug the dug out and the bloody gun was still there on the tripod like you know. All I had was a rifle really. And it was lucky for me really when he said you take over. No, no, not joking. That man. Less than five minutes he was dead. Whether they shot him from behind or what. Must have been cause he was in this side, then this side, so couldn’t have been from the bloody front. With all these troops. A big man. He looked like Americans like from the distance. It was dawn like you know. We couldn’t see properly. And I thought bloody queer all that lot over there.

CB: Were the British firing much or did they not. Were they not firing?

FW: No. We were firing. They were down. We were firing down, down a, down a slope like that see. They were up there on top of us this lot. We realised where they were. Because we realised where they were. This one came up from behind and when we turned around — I thought Christ this is it. He said, Raus, Raus. I don’t know how many Raus man I don’t know , rise I suppose, I think. And that was it. Now I told you we for four of five hours we were carrying German wounded from there back and forth. Quite a lot of our lads were killed with our shells firing over, see. They were firing over the Americans The American flag I suppose. Britain was Montgomery was up there in the Adriatic side got him. So it was the American troops or British was firing the bloody guns.

CB: So the artillery were firing over you?

FW: The artillery were firing over the German lines. Well we were in the German lines we were.

CB: Oh you were in the German lines were you?

FW: Of course we were, right. Of course we were.

CB: Right.

FW: ‘Cause a lot of the lads got. Three of these I know got killed there with shells. Yeah. In a way I was lucky all the way around. In a way I was lucky.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Because if he hadn’t said to me change that, change around it would have been me not him. He was older, he was older. Thirty five, thirty six I imagine like. He should never have been there really cause he come out of the pay corps or something. He shouldn’t have been there. But if it wasn’t for him saying turn around, change around it would have been me not him, poor bugger.

CB: So did you have any chance to fire against the Germans at all yourself?

FW: We were firing down on them. Because you couldn’t see, trouble was it was getting, it was still dark sort of like of you know. Up till then we hadn’t seen anybody up till the day before, the Wednesday. It could have been anybody, nothing. No call. No, nothing. Nothing at the back. They must have come in the early hours of Wen, Thursday morning. But they have crept up somehow or other without us realising it, in the dark and we couldn’t see anything. And this lot behind I thought they were Americans to be sure. There was masses of them like you know. They were German paratroopers they were. They didn’t land, they must have been. They didn’t land with the parachutes they were. That’s where they were you know, the paratroopers. We didn’t stand a dog’s chance did we?

CB: So were you firing yourself, were you using a rifle or were you using a Bren gun.

FW: A Bren gunner.

CB: You were a Bren gunner were you?

FW: A Bren gun we were firing. Yeah. We fired yeah. But at the moment you couldn’t see anything in the dark obviously. So close. I mean, you were more or less in the dark they caught us in the dark didn’t they?

CB: How many magazines did you carry with you for the Bren gun?

FW: Oh I don’t know really. It didn’t hold that many you know, not really. More like it was on a belt nothing like that. A magazine they were. Not that very many. You got to keep filling them up all the time. Worse, oh I don’t know. I was lucky in a way. Well I was lucky. Well If it had have been me I would have been bloody dead if it wasn’t for him moving, saying change over, would have been me. So it was the luck. I hadn’t seen anybody dead before.

CB: Right.

FW: To think he died although I was carrying back and forth. The ones we carried they weren’t dead they were wounded like you know, but they were all piled at the back behind the aid post. I couldn’t believe it. They were all like piled on top of each other. I wouldn’t have thought it was that, how they got that many there.

CB: You didn’t see what they did with them after that?

FW: Oh No. No. We moved off. In later in the afternoon we sort of moved down in some gully out there. Inside Hills, big cave thing, I was in there and then we were moved out into the Rome then. Empty film studio. Well they apparently said they were film studios. It was a big place anyway. And there were bloody loads in there, must have been more American than British. But we were with the American 5th Army we were attached to them see. There were more American than British in there. Of course from then on we went to another camp higher up the road. I think British soldiers from the Middle East, Far East — not the Far East. Middle East. Were captured by the Italians you know. I’d been there for a while. Katrine I think it was. Something like that it was called. I know we were on a railway and a walk down into this camp but that was very primitive that one. I tell you. Plenty of Americans there as well.

CB: So did you have anything to do with Americans or you just knew —?

FW: Oh mixed with them. Yeah. We were all in the same bloody combat. Combat. Yeah. They were alright. All blokes.

CB: In in the prisoner of war camp they were just British were there? Where you were?

FW: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Well when we were in Stalag Luft 3 there was a compound. There was like a French compound with all the wire all the way around it, you know like you know. The British compound. Three or four other nationalities like. You didn’t sort of mix with them much like. The British kept to themselves and they kept to their selves. Yeah.

CB: So in your part of the camp were there any NCOs or were you all privates?

FW: Oh there were NCOs. Corporals and that were with them.

CB: Corporals right.

FW: Mostly but —

CB: Ok so —

FW: And Sergeants — they didn’t have to work.

CB: No. Right.

FW: No.

CB: No. So that.

FW: We did have a sergeant in the camp where we were. Patterson his name was. Oh no, I remember Jock Patterson. And he was. He was really good. He was. There was only fifty of us where we were with him, so it was alright. So there weren’t too many of us like, you know.

CB: I know. And what was the camp made of? Were they?

FW: Well a big building.

CB: Big. Were they sheds or were they brick?

FW: By the time you got a record there, don’t know where they hell they got a gramophone came from. One record. I’ll always remember if I had a dime for every time it missed you. I played it over and over and bloody over. Day after day after day after day. The only record I had. I played the bloody heart out of that thing. I tell you about it didn’t I? That’s the only record I had was that one. Long, long time in Texas, if I had a dime. I thought yeah. If I had a dime and all.

CB: So in the camp you’re — is this a wooden building or is it a stone or brick.

FW: No. No. Not brick. It was semi brick.

CB: Right. Yeah

FW: It was on three storeys you know because there were seven hundred and fifty of us in there.

CB: And what did you sleep on? Were they beds or?

FW: No.

CB: You were on straw .

FW: Yeah.

CB: But were they bunks.

FW: No. No. We did have bunks.

CB: Ok.

FW: Two bunk beds they were.

CB: Right.

FW: Yeah.

CB: Just in twos.

FW: But the one in. When we first went to we had three bunk beds they were.

CB: Right.

FW: Christ. Higher than the ceiling they were. You would bloody break your neck falling out of there.

CB: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And what about the ablutions Was there, for each area did they have the proper washing facilities or what?

FW: Do you know I can’t bloody think to be honest. You know. Must have. Yeah. They must have had toilets up there. We all went there anyway I must say. I myself found a place for washing. There was for like swilling down and washing down. But it was very primitive you know. It wasn’t very clever I can tell you.

CB: Hot and cold water?

FW: Cold water. Yeah.

CB: Only cold.

FW: Eh?

CB: Was there hot water as well?

FW: No. Just cold water. No. No. No hot water.

CB: And then there was a cleaning detail was there? So you had, did you have a rota for cleaning?

FW: No. No. I didn’t —

CB: How was it cleaned?

FW: I didn’t do any cleaning. I didn’t do any cleaning.

CB: You didn’t have to clean it?

FW: I didn’t anyway. Somebody must have, I probably. I don’t know. I mean what you’ve got to think about. So many people there, you see. It might be three storeys see. One on the ground floor. One on the middle and one on top.

CB: And what about eating. Where did you eat? Did they have a large canteen that you ate in?

FW: No. No. No. You ate by the bed.

CB: How did they distribute the food?

FW: With a table. Sorry. A bed with a table.

CB: Right.

FW: No.no. no.

CB: How did they distribute the food?

FW: The cookhouse. You had to go. You queued up and got your food from there and go back in.

CB: So you walked to the cookhouse?

FW: You walked there. Yeah. Yeah.

CB: And that meant it was a hot, hot meal was it?

FW: Well [laughs] yeah but a lot of it was bloody sauerkraut, which I didn’t really like very much. I had to eat it. I didn’t like it though. I’ll tell you. I had to eat something. But as I say wasn’t for the Red Cross parcels we’d have in big trouble. At the end of the war see, well that ended that year I mean. ’44. It wasn’t in to ’45, coming through then you see.

CB: Well the Germans themselves were short of food weren’t they?

FW: I suppose they were. They weren’t much better off than we were really. We never mixed with any of the civilians living around in the, village, the little villages, around there but of course we were wired off. You couldn’t get out anywhere. We never actually mixed with them. No.

CB: So you were out from seven ‘til five.

FW: Yeah.

CB: Working in the pipe factory.

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: These pipes are earthenware pipes. Not steel.

FW: Oh no.

CB: Not metal are they?

FW: No. No. Earthenware. No. No. No. No.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Up at the top. They done them. On the top. They done them up there in the kiln, up the top. Then dropped them into the kiln. Filled one side up that way. Then the other side. Then through the middle you know. Then they’d brick it all up. Light it up. Fire it up. Forty eight hours probably, something like that now. We didn’t have anything to do with it. We were just unloading the wagon we were like. From the coal as I say —

CB: So the coal came in?

FW: And they put back in.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Where the coal came out of we put the pipes back in.

CB: Right.

FW: Put straw on the floor, pipes on top, straw on top, and take them, then down the other side, then went down through the middle the same aye. We didn’t bother if we were dropping them they bloody broke we didn’t really bother too much.

CB: What about safety there. How many?

FW: Oh. No. No. No.

CB: Were there any accidents?

FW: Not really. Not that I can recall. Only one thing. One bloke. He didn’t do it deliberately when he, when he pulled one of them kilns you know, when they cooled down apparently he messed on it, pulled half the bloody bricks, pipes fell down. And they took him away you know. We never see him again. I don’t know what happened to him now. Never know what happened to him. You can’t encourage that you know. Messing about. And I don’t know what happened to him. Nobody did. Never seen him again. Yeah. Never came back again. So what happened to him I’ve no idea. And that RAF bloke base was right next to us right next to us. Luft 3.

CB: Yeah.

FW: It was.

CB: Yes.

FW: Like not right not adjoining but it was there you know, the gap was there. But it was there.

CB: What were they doing? Could you see what they were doing?

FW: No. Couldn’t see. No.

CB: Right.

FW: Not really. No. Not really. But beyond there was another compound. Other prisoners in there like you know. You weren’t in the end part of it.

CB: So you’ve got seven hundred and fifty people in the building.

FW: Yeah.

CB: In this camp.

FW: Yeah.

CB: How did the organisation, authority work? There was a sergeant running the whole thing or was there somebody. In each room was it?

FW: Oh well we had. More or less sergeant. Somebody in charge of each group like you know.

CB: In each room was there.

FW: There was only fifty of us so we weren’t too bad like you know. What factory they worked in is different factory than was the bigger factory than we were obviously. We were only a small place actually.

CB: What were they making?

FW: I’ve no idea you know.

CB: Right.

FW: No idea now. No idea, never went there. I’ll always remember the old, old boy I met who owned the place. Mr Schutler his name was. And if you spoke a bit of German — ‘Yah yah gudt, gudt.’

CB: So the factory was run by Germans.

FW: Oh yeah. Yeah.

CB: How many of those would there be running the factory?

FW: Only the ones I see other than the ones on the top doing the, doing the. Whether they were German I don’t know, doing the actual pipe round the top, like you know. There was only the two of you more or less. The three of them on the outside. They were German outside with us. But they never, they never bothered us much. Not really.

CB: So the camp has got accommodation which is substantial buildings?

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: How was the security operated. There was a fence all the way around was there?

FW: Well I suppose so. At night time they took your boots and your belt.

CB: Yeah.

FW: And locked the place up then.

CB: Right.

FW: You couldn’t get out anyway.

CB: But there was a barbed wire fence was there. All the way around?

FW: Oh all the way around yes.

CB: How tall was that?

FW: Oh it might be bloody fifteen, twenty foot high I should imagine. Right high one. Quite high. And nobody ever escaped. I don’t think anybody ever bothered I don’t think, you know. Whether they tried I don’t know.

CB: And how —

FW: Nowhere to go to anyway.

CB: No. What about the German staffing. What were the guards. How many guards?

FW: Oh there must have been — well there was a sergeant. If they called him a feldwebel usually called him a sergeant instead, and it was him. He was a cocky little sod he was. Wear a hair net. Used to wear a hairnet. In his hair, and was one of them was he like that. There were about half dozen of them, more than that I suppose. What you’ve got to watch is the black shirts. Gestapo, come around and mooch around. That’s what you’d got to watch. They were always tall. Mind you they mainly looked tall but they were all in black you know, uniforms they were. They were crafty buggers they were. But other than that the German troops we never had no problem at all. Because they were the same as we were, I mean there was nothing we were doing to them than they were doing to us. Couldn’t do anything. Course as I say in the latter end of December I moved from there into the main camp. Never saw any. The only one I saw Bert Weston, when he came to our house in Oxford after the war. But the rest I never met them again. Quite a lot died going on the long. It was cold see. Marching back from bloody East Germany to where they went to .

CB: How long did that take?

FW: I don’t know. Took days and days I think. Three days. How they stopped at night I don’t know really.

CB: How did you get food?

FW: Who?

CB: When you were on the march. How did you get food?

FW: Oh we didn’t. I didn’t go with them. No, I. The Russians released us. Come out through Poland we did. We went East and they went west.

CB: Yeah But how were you controlled and —

FW: We were on our own then.

CB: Right.

FW: Yeah.

CB: Entirely.

FW: Yeah. Entirely on our own yeah. They Russians would have bypassed us by then. When we first saw them you know we couldn’t believe it. There would be a little horse, little horse and cart. Can’t be anybody surely. I was hiding behind a massive great bloody tank I think. I thought the Tiger tank was big, this bugger was bigger than that. I tell you. And they came in, in masses then they did, came bloody well right through you know. But they really you know. But they overrun Berlin the Russians did. Right to Western Germany they were really. But they being the four, the American British French and Russian. They parted in four sections but really and truly they were right into West Germany really the Russians were you know. They could have stayed there. There was no one to stop them. They didn’t. They moved back into East Germany you know. Because then again see, America was crafty see. They were a rich country. They pumped money into East Germany, West Germany. The Russians couldn’t put money into east Germany because they were poor themselves see. Because that made them look worse you know. That they’d been treated badly. You couldn’t be. Not that they were treated badly. They had no money to give them. It’s a ruddy cheek when you’ve got when there was a problem. There was a French part, British part, Russian part and a American part.

CB: After the war.

FW: After the war yeah. Berlin. Split into four.

CB: Sure. Now back in the camp how often did you have to parade?

FW: Oh our numbers were counted our number every night. Oh yeah counted.

CB: Outside they counted you inside did they or in? In your —

FW: They had to break them down to count how many were still there like. You made sure every bugger was still there. Oh yeah. Oh yeah. But then to be honest, I never had any trouble with German troops at all. Not, not the ones I met anyway. To be honest. Not at all.

CB: Did anybody try to do trading with the Germans, To give them something?

FW: No. I don’t think so. We had nothing anyway did we?

CB: Did you have chocolate?

FW: Well we had chocolate. I don’t know. I didn’t enter in to it with them anyway. Don’t know. Because once. Red Cross Parcels, that’s right. I don’t know. Because when they came in with the Red Cross. Nothing to do with the Germans. Nothing to do with the Germans the Red Cross parcels.

CB: What was the best thing in the Red Cross parcel?

FW: Well it was different. On the box was the names of the city. It could be Leicester, Birmingham, Bradford. Different places and they all more or less. Always put the same thing in that they you know, that they would put in each, every time. So people used to say, ‘Well, we’ll swap the box for this one or that one,’ you know. What we wanted. But we just stuck it with what we got. Bloody lucky to get that. Didn’t bother too much. Some had cigarettes in them and all. I’ve seen the packets in the tins like you know.

CB: What would the tins have? What would the tins have inside them?

FW: I don’t know I couldn’t tell you. We never had any. Well ones that didn’t smoke done alright see. They could Park Lane cigarettes for food see. They done alright they did.

CB: So when you were in the camp did you feel hungry? Or were you satisfied?

FW: Well we weren’t really hungry. I didn’t say we wouldn’t have shovelled a bit more, you know but still we managed. Got away with it. Yeah. It wasn’t pleasant, I can tell you. We didn’t know what was going to happen see. That was the problem. But the thing was we never knew what was going to happen. That was the problem. We knew in the end what happened but we didn’t know in the beginning. It could have been anything.

CB: Did you get, what sort of news did you get in. Had someone got a pirate radio?

FW: No. Not really. I did find out eventually. They started a second front for what’s the name.

CB: D-day.

FW: There was something on the move.

CB: For D-day.

FW: But this bloke with me was captured at Arnhem. That was September.

CB: Right.

FW: He was captured there, and so we knew they were doing something yeah. And they was warned there you know. Apparently the German panzer division were in there in Arnhem. They were. Apparently the Dutch underground told them not to come and they wouldn’t listen. They shouldn’t have come because all them blokes were captured see most of them. A lot of them were killed or captured. In Para. In Arnhem, a lot of them. My mate, well my brother’s mate he was a sergeant in the paratroopers and he did escape. He didn’t give up. He didn’t. Glen didn’t get captured, but a lot of them did. Yeah. At Arnhem. A lot of them were bloody killed and all, I tell you. They were warned really not to come really. There were two panzer divisions there.

CB: Yeah.

FW: In Arnhem. From that area.

CB: So some of those came to your camp, In the camp?

FW: No. No. They didn’t come to our camp. I met them afterwards. After we —

CB: Oh right.

FW: Got out of the Stalags. When the Russians released us. I got and met them then. These two RAF blokes.

CB: Right.

FW: They weren’t officers or nothing. I don’t know how they got there to be honest. You know. They weren’t all sergeants in the planes. Were they?

CB: Well it was a mixture.

FW: Maybe. It could have been that then.

CB: In the, In the camp. What did they do about medical care and pastoral care, So were there chaplains in the camp?

FW: No. No. No. There wasn’t much medical care then if anything in the camp. Not in our camp anyway.

CB: If somebody became ill what happened?

FW: Well as I said with me they sent me back to main camp. That’s what they’d do.

CB: And in the main camp there was a —

FW: There was, there was a bit of a surgery there. Yeah.

CB: Right.

FW: Yeah.

CB: And dentists?

FW: Oh I don’t know about dentist. I don’t know, never knew a dentist there. I don’t know.

CB: No. But the people looking after you. Were they German medical people or British?

FW: German. Most of them. Yeah.

CB: And the doctors.

FW: I should imagine they were German. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

CB: Right. So what was the thing that you remember most about the war?

FW: Well, to be honest it was a bloody escape I had I reckon. That was the main thing really. I don’t think they were like the same people like we were. The German soldiers. You know. It seemed so useless like you know. It was just had a regime that was corrupt. That was the problem. And of course, they were caught on the nap see. They were caught. The Italian front was still there. The Russian front was still there, and then of course we landed in France. They were on three fronts see. So that’s where you got caught. But in Stalingrad, they reckon, the Russian camp, eight hundred thousand German troops. In Stalingrad. They were caught in the winter see. They didn’t realise how bad the winters were in Russia see. They were caught there. They had a hell of a mess in Russia.

CB: So how did you get news in the prison camp of what was going on elsewhere?

FW: Not a lot. No. Not a great deal. No. No. We did nothing. And more or less when I got to main camp when I told you I got back there.

CB: Yeah.

FW: That had a bit more information. We got nothing back in the working camp. No. Nothing there.

CB: Did you find out how they got information?

FW: No. Not really. There was a bloody rumour I know. But they said the second front had started. So, but we knew that because after when we got to know each other this bloke landed at Arnhem so I knew the second front had started. But other than that.

CB: Right.

FW: But not a great deal

CB: Well I think we’ve done really well. We’ll pause there. Thank you very much.

FW: Righto.

[recording paused]

FW: Really to prove I’ve been there I think.

CB: This is the British Legion people.

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: Because they were mainly First World War were they?

FW: First World War veterans see. Yeah. You see.

CB: Right.

FW: And they knew all the — ‘cause then they were mostly in their sixties or seventies you see probably. It didn’t really [pause] down Oxford at one time it was very stuffy down there you know. So we did go down quite a few times and I said to Trevor, ‘What do you reckon?’ He said, ‘They don’t even want us here do they don’t look like it, so we didn’t bother then?’

CB: What was it about them do you think that they want to keep apart?

FW: I don’t know. I think they’d been on their own so long, you know. They thought it their place and not for us to be there I think. Young people. We were only in our twenties. At twenty two you. We were quite young compared to them. And they probably thought we don’t want none of them young ones in here.

CB: What sort of ages.

FW: They were running it see.

CB: Yeah.

FW: They were older. Then were in their sixties mostly.

CB: Right.

FW: First World War. Other than that. And they didn’t ever give you any encouragement to stay anyway. Not really. Never actually said anything in particular, but you got the atmosphere. You could feel that it was there. It was not — you weren’t really welcome there.

CB: What did you think there. Were they. To what extent were they comparing what they did with what had happened with you?

FW: No. They didn’t say nothing much at all actually. Seemed more like wanting to keep to themselves you know. That’s the impression we got like, you know.

CB: Yeah.

FW: They didn’t seem to want us there like, you know. They didn’t actually say they didn’t want us there. The didn’t say that but the impression we got that you were sort of given the cold shoulder like, you know. We went in four or five times but it never seemed to change much so we didn’t really bother to go back.

CB: So down at The Legion was there much military talk or did they avoid talking about their experiences?

FW: They didn’t say much at all of anything. Didn’t seem to. No.

CB: Right.

FW: They seemed to be such a long time being there they seemed to run the place. It was theirs like. Not ours. Sort of thing. So we left them to it. Fair enough. I was about twenty. Well I was about twenty one then probably, or twenty. Twenty one. The other chap was a bit older than me twenty three probably.

CB: But you’d been in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry.

FW: Yeah.

CB: And was there an Association for that as well?

FW: There should have been really. In Oxford. Wouldn’t it. Should have been. Yeah.

CB: But there wasn’t?

FW: As I said, wasn’t there long. We didn’t find out. Maybe four or five times we went there.

CB: Yeah.

FW: They didn’t seem to alter much so we sort of felt sort of shut out sort of thing, so we didn’t bother again.

CB: Yeah.

FW: And they had been there such a long time they had, you know, they more or less thought it was theirs like. You know. Probably was. I don’t know.

CB: Yeah.

FW: That’s why we didn’t bother too much. But other than that I never bothered after that. Never went anywhere after that. The only good thing when I was in Colchester was the Salvation Army. Always having a cup of tea in there. Always had a one there. They were good they were. I always give something to the Salvation Army. Even now.

CB: How did you take to being in the army? You were called up and this was a completely new experience, so how did you take to that?

FW: Well I got used to it in the end I mean. I was eighteen in the January and this was March. Well I had no option really. I was in there you know. And you got used to it in the end. But you know. The Hampshires. The Hampshires were go slow walking you know. When you got the Oxford Bucks thump thump thump.

CB: Yeah.

FW: And you got the second Oxford Bucks they were even bloody faster they were.

CB: Yeah.

FW: And we always had, always had black. Heavy black buttons. Everything. All black coats with black buttons and black blossoms on the head you know, on the hat.

CB: You said there was a lot of marching.

FW: Yeah.

CB: So how did you take to that?

FW: I always remember when we were in New Barracks in Dover. A big barrack. There was, always remember. There was artillery blokes there and they were sat around the bloody thing one of them said what a lot of clowns they were. [Clapping]. I said yeah. Bloody hell Yeah. They got you marching up and down. My. [makes sound] you couldn’t bloody, you couldn’t meet the others, you were so fast with walking. A hundred and forty five steps to the minute.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Cor. Bloody hell.

CB: But the idea was to keep you fit.

FW: Yeah probably was.

CB: And to move you quickly.

FW: The quicker you marched the quicker you got there.

CB: So what physical training did you have to do in those days? As well as marching?

FW: Well you did PT and all that.

CB: Where was the PT held, was it?

FW: There was no gym I don’t think, or anything like that. Outside mostly. When it was dry that was. We had these little anti-tank guns in the end. There was something, a carrier. It had no steering wheel. It had two, two handles. And tracks you know. You know, one tracks left on you know. Pull it left, one to the right. We tried to drive them. Very queer they were. Cardinal hoist or something they called them. They’re supposed to pull a gun behind them or something. Well little, small gun you like you know.

CB: What sort of gun was there in there?

FW: Well that would be behind, whether it was used or not.

CB: Because these became Bren gun carriers. They were called Bren gun carriers weren’t they?

FW: Maybe they were yeah. They were queer things to drive. I’ll tell you that. They had no steering. They had handles you know.

CB: Yeah. But they could go over any kind of ground.

FW: Yeah. It was on tracks. Oh yeah. Tracks they were on.

CB: How many people could be in that?

FW: I don’t know. Well in the front, You could get three in the front easy. How many you could get behind I don’t know. I couldn’t tell you?

CB: And the gunner. Were there two on the gun as the gunners?

FW: Yeah.

CB: How many people?

FW: Never actually used one. Not really. They bought it in to show us what it was like you know.

CB: Oh I see.

FW: Nothing, nothing in them when we had it. Show how it worked more or less. It was queer. Because somebody could drive probably. I couldn’t drive then, and so it was twice as hard for me. Somebody who could drive could probably have got the hang of it like you know.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Small artillery guns. They were. They weren’t very big. You could move them around. On two wheels like you know. You could pull them around like that.

CB: And these were infantry?

FW: That was in Dover that was.

CB: These were for the infantry.

FW: Infantry. Yeah. Yeah.

CB: Anti-tank.

FW: Infantry. Yeah.

CB: And how often did you?

FW: We had the PIAT mortar.

CB: Oh the PIAT mortar. Yeah. Yeah

FW: The damage they could do. They could do some bloody damage I tell you.

CB: Yeah.

FW: Yeah.

CB: So how much live firing did you get?

FW: Oh I we done a bit yeah of what’s the name. On the ranges with a rifle, and make a Bren gun.

CB: And if you achieved a certain level you’d get a marksman’s badge.

FW: Yeah. Yeah.

CB: Did you get that?

FW: No. I wasn’t very good. The trouble with me I couldn’t. If I closed one eye the other buggers would close up as well partly. You couldn’t see properly. No. I wasn’t very happy in the army I can assure you. Navy I wanted to go in. not the bloody army. All my mates were in the navy.

CB: Were they? Yeah.

FW: I wanted to go in the navy. Didn’t want to go in the army.

CB: How many of those survived the war?

FW: All of them three did. Yeah. My brother. He was my brother’s wife’s brother. Joe. He wasn’t a cousin. He was on the Russian convoys. It was really bad on the Russian convoys in the winter. Snow and ice.

CB: So you were in the army. What did your brothers do?

FW: The oldest one, not next to me the older one. They reckon he couldn’t do it, but he wouldn’t have passed the army anyway. Tom was. He was in for six months. He was. He used to work on the presses with all the sheet metal. And I think they wanted people back in the factory like you know. We were getting very short. So he came back, a limited time. He never did go back to the army. In the army about six months and he never went, never need to go back. He stayed in the pressed steel all the time.

CB: Because it was?

FW: If I’d stayed where we were that aircraft thing. I’d never have gone in the —

CB: No.

FW: Because like a mug I went with all that lot. Course the other two went in the navy and I went in the army.

CB: Now when you came to the end did they give the option to staying on in the army?

FW: No. No.

CB: They didn’t.

FW: They didn’t do anything like that. I didn’t want to stay in anyway. I wasn’t keen on the army I can assure you. It wasn’t my first priority.

CB: What was it that you didn’t like about the army?

FW: I don’t know. The comradeship was pretty good like you know. But I don’t know, not really.

CB: And you came, you had a number of friends. How many of those became firm friends?

FW: Well the ones, well when I left Dover none of my friends come with me.

CB: Right.

FW: The bloody problem was still there. And one of them I found I didn’t know actually he lived out in Woodstock not far from Oxford, and I was going to visit him I didn’t go. Luckily I didn’t because apparently he got killed in France. He was twenty he was, probably. Nineteen, twenty. So I would have been. If I’d have gone to his house it would have been bit bad wouldn’t it. I didn’t know that. Because when I was on his Rover line his foreman told me he was from Woodstock. I come from Woodstock he said. And did he know a bloke call Bill Brooke. Oh yeah he was my mate he said. How is he now. He got killed in France he said. Twenty he was. Dispatch rider note delivered telegrams on a little motorbike around he did there before the war like you know.

CB: Oh did he.

FW: But he apparently got killed in a. That was the only one. Me and him was only two together more or less, the only two together more or less.

CB: And when the war finished to what extent did you discuss what you’d done in the war with other people?

FW: No. never. Never much with anybody about it. Actually I was for about eighteen months I was very how do I put it. Very, very quiet. Never said anything to anybody. I don’t know I just I got [unclear] I couldn’t believe what happened to be honest. Not really.

CB: What do you think caused you to be so quiet?

FW: I got a bit depressed. And all that you know and all that.

CB: What caused the depression?

FW: I don’t know what it was. I don’t know. I just didn’t. Couldn’t seem to cope somehow. I was all right after a while, fortunately. I was alright working in the old pressed steel. We were making fridges then.

CB: To what extent do you think that being in a prison camp made you depressed?

FW: Well it didn’t bloody help much I don’t think. Not really. But what I mean we’re all the same together. I mean there’s not much you can do about it. We were there and that was it. But the answer was the real problem, we didn’t know what was going to happen next. You know what I mean? If. Sort of thing. We didn’t know what was going to happen.

CB: No.

FW: Do you know what I mean?

CB: Yeah.

FW: I was always if they could have killed the bloody lot of us. They could have. One thing I’ve got to be honest. The Germans I met, there can’t be that many, but we had no problem with. There was no animosity. You know charge, or ordering you about or anything like that.

CB: What sort of ages were the guards?

FW: Well some of them were older. They weren’t young. They weren’t young. They were all forties and all more than you know, fifties. They weren’t young. No. no. I think they’d probably had the senior service or something like that.

CB: Too old for front line service.

FW: Oh yeah. Yeah. Only the sergeant was. He was a cocky one he was. Always wearing a hairnet and all.

CB: He got very long hair had he, what?

FW: FW: They called them a feldwebel used to call him if they were a sergeant. Feldwebel or something like that, and he wasn’t very big either. He wasn’t like a German or anything. He was quite small actually, fair haired bloke. Always the one with the hair net on that bugger was. Why have you got that on for. He went to bed with a hairnet on I expect. He was a bit of a cocky one.

CB: Yeah.

FW: But there were rest were alright. They never bothered you.

CB: What about the commanding officer of the camp. Did you ever see him?

FW: Never see him.[ unclear] They more or less left us to ourselves, more or less, I think more or less. Normally we didn’t bother them, they didn’t bother us.

CB: You see in films the complete, what shall I say? Were all the prisoners would be put on a parade together. The full contingent.

FW: Oh we were all counted.

CB: did you have to do that?

FW: Oh yeah. We all got counted at night time. make sure we were still there.

CB: No. no. but did they have everybody together in the parade square?

FW: More or less. Yeah.

CB: They did. Right.

FW: Oh yeah. But they didn’t order you about, nothing like that. No. no. What we do what we like then. wander around where you like. I mean it weren’t a big, big. It wasn’t a big compound. Not that big anyway. It was a fair size, but not for that amount of people. Not really. All being together. No.

CB: Well there were ten thousand in Stalag Luft 3.

FW: Right. Thank you. When we were released, you know. When we were released we wandered and I could see where, you know like when you walk in file. Troops walk one behind. It was row of about eight of them. Germans all dead on the grass. They’d all been shot. One behind the other. And there was a Russian soldier there, and a German soldier as close as I am now there, next to each other. I’ve never seen so many dead people.

CB: And he shot him.

FW: They must have shot each other. Probably. Most probably. Yeah. I’d never seen anybody dead before. Till like all these were shot. Never seen that many after all that lot behind me at that aid post honestly we were, I’m not joking. They were like bricks you know. One like that. On top of the other. They were that bloody high. They were about four high, they were.

CB: This is at Anzio you’re talking about?

FW: Four high they were. Yet I can’t understand where because the amount I saw a lot of the bloody dead. I Didn’t see anybody get killed.

CB: Yeah.

FW: See a lot of wounded there so I don’t know.

CB: Did you have to carry the wounded as well?

FW: Oh yes. We had to carry two of us. One in front, one behind carried the German wounded on a stretcher.

CB: On a stretcher?

FW: Oh yeah. Yeah. A lot of our lads. Two of. Two I know two of them got killed. By our shells landed on top of them around that area or what’s the name.

CB: Oh while they were carrying the stretchers.

FW: While they were carrying the wounded yeah. We were lucky then.

CB: What was the reaction of your comrades to see that your own comrades were being hit by their own artillery?