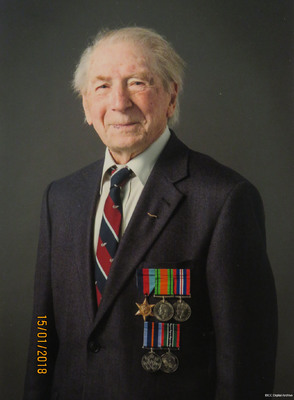

Interview with Maurice Vivian Askew

Title

Interview with Maurice Vivian Askew

Description

Maurice Askew volunteered for the RAF and began training as a flight engineer. He was posted to 207 Squadron at RAF Spilsby and his first operation was to Berlin. On his last operation his aircraft came under attack. He was knocked unconscious as he bailed out of the aircraft and regained consciousness just before he landed on snow, which he first thought was the sea because of the appearance of waves. After a varied post-war career, Maurice became a set designer for Granada television before emigrating to New Zealand. His memoirs were published under the title, “No Caviar for a Kingfisher.”

Creator

Date

2018-01-15

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

00:22:06 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AAskewMV180115, PAskewMV1801

Transcription

GT: This is Monday the 15th of January 2018 and I’m in the home of Mr Maurice and Doris Askew of Christchurch, New Zealand. Maurice was RAF Volunteer Reserve number 1098180. Maurice was born 6th August 1921, Redditch, Worcestershire, England and joined the RAF in March 1941 as an aircraftsman. He worked in maintenance units and then volunteered and trained as a flight engineer for aircrew in 1943 at RAF St Athan, and qualified as an FE sergeant. He crewed at RAF Syerston, Number 5 Lancaster Finishing School and joined 207 Squadron at RAF Spilsby. Hello, Maurice. Thank you for allowing me to interview you for the IBCC Archives.

MA: It, it will be a pleasure. I hope it will be a pleasure talking to you.

GT: Excellent.

MA: We’ll see. Yeah.

GT: And we also have your lovely wife Doris sitting here too.

MA: Right. Yeah.

GT: And she’s going to help us with some of the bits and pieces to fill in too. So she’s, she’s very much with it and exactly what we’re, just Maurice can you please tell me a little bit about where you grew up and why you wanted to join the Royal Air Force?

MA: I grew up in a small town in Worcestershire called Redditch and when the war broke out it was necessary for me to be in one of the services. If I didn’t volunteer for any service it would be the army. So, I didn’t fancy the army but the RAF was waiting to welcome me and I joined the RAF in [pause] when?

DA: ‘41.

MA: 1941. Yeah. 1941. Now what?

GT: And as you joined up as an engineer fitter. Aircraft technician.

MA: A flight.

GT: An aircraftsman there.

MA: Yeah. An aircraftsman.

GT: Yeah.

MA: Okay.

GT: So, you were responsible for engines and air frames.

MA: Yeah. Yeah.

GT: And from there you went, still wanted to go in the air didn’t you?

MA: I’m trying to —

GT: You wanted to become a flyer.

MA: Yes. So, I was based in —

GT: In RAF St Athan.

MA: St Athans. Yes. But after a time I felt I should be flying and so I transferred to training at Spilsby to become a flight engineer which was a step beyond a mechanic I suppose.

GT: How was that training? Did you, did you find it difficult moving from a ground job to an air job? Or was it just a simple? It was easy.

MA: No. No. It was just a straightforward move from one job to another.

GT: And, and the flight engineer job working on the aircraft as a flyer was no different you thought.

MA: I don’t know how I can put it quite. I’m sorry.

GT: Your, your experience though Maurice was what you wanted to do. You wanted to fly and you achieved that. And so, so then the moving to finding a crew. You went to Syerston, to Number 5 Lancaster Finishing School.

MA: Yes.

GT: Can you describe how you found your skipper and your crew?

MA: And then a number of flight people got together in the, in a hall where we sorted ourselves out. Pilots, flight engineers, and so on. And I’m not putting this very well.

GT: You’re doing —

MA: My wife can explain.

GT: You’re doing very well. That’s fabulous. Yeah. That’s the information we’re after. And therefore you found your skipper.

MA: My skipper. How I came —

DA: Wally Jarvis.

MA: To get the link up with Wally —

GT: Yeah.

MA: I’m not sure. We just liked one another although in a way we were quite different. Wally was a light boxer actually. I wasn’t a boxer at all. But we got on so well somehow and continued our training together as pilot and flight engineer.

GT: And you were joined by your, you joined up with a navigator and wireless operator too.

MA: And in a similar way we picked up navigators and gunners. I’m not putting this well.

GT: Yes. I’ve got, your navigator was Sid Pearson.

DA: Yes.

GT: And your wireless operator was Jeff Moray.

MA: Yes.

GT: Is that right? Yeah. And your bomb aimer was Phil Paddock.

MA: That’s right. That’s the name of our crew.

GT: Yeah. And then you had two Canadians as your gunners.

MA: Yeah.

GT: That’s great. So then you were at Spilsby.

MA: That’s right. Yes.

GT: Yeah.

MA: We went to Spilsby where we trained in various aspects of Air Force life I suppose [pause] sorry. It’s gone. It’s gone.

GT: Yeah. That’s good. That’s good. So, at Spilsby. That’s in Lincolnshire, isn’t it?

MA: Yeah.

GT: So, so you weren’t far away from the main action of all the airfields. So, you did your first operation and you were just saying to me that was Berlin, that was your first op.

MA: Yes. My first op with the crew was to Berlin.

GT: And that was about February 1944.

MA: Yes. Yeah. It all went quite well actually and we returned.

GT: It was very busy night you said in your book. There was lots of fireworks going on.

MA: Berlin, of course was a major target in those days. I just remember lots of fireworks going off. You know —

GT: And you, and you certainly managed to get back okay so that was fabulous. But, but it was, it was the next night, on your second operation of your crew on the 19th and 20th of February and you were flying in EMA for Able.

MA: Yeah.

GT: Aircraft number EE126.

MA: Yes.

GT: And your target was —

MA: Leipzig.

GT: Leipzig. Can you, can you remember what happened?

MA: We set off for Leipzig and [pause]

GT: You had some, you had a Messerschmitt 110 come at you didn’t you? Your gunners, your gunners took at them.

MA: As we, as we reached the target going in there were fireworks and so on in front of us we were attacked by a Messerschmitt.

GT: And that set you on fire so you had to get out, eh? And I see you’ve written in your book that Philip was a little bit stuck trying to get out so you gave him a bit of a push to get out. And Wally was blown out of the, out of the cockpit. So they were saved.

DA: Yes.

GT: Yeah. And what? You managed to pull your rip cord, okay.

MA: Automatically I presume. As I went out.

GT: Because you knocked yourself unconscious.

MA: And the side of the cockpit exit hatch hit me and I passed out to come around as I was just above the ground which I thought was the sea because of white waves. But suddenly as I hit the ground as it was I passed out again.

DA: It was snow.

MA: And of course, the ground had been covered. Was covered in snow at that time.

GT: And you were rescued? You were rescued then, and a family took you in and looked after you. Is that right?

MA: This is a mess. I’m sorry.

GT: Yeah. Maurice, you’re doing fine. So, so in this case though you survived the snow and you were taken prisoner of war.

MA: And picked up by some farm people who took me to their farmhouse, patched me up as best they could, gave me something strong to drink and there I stayed for two days perhaps until the RAF sent RAF police to pick me up.

DA: Well —

MA: Yeah. The German. German police.

DA: German.

MA: German police.

GT: Yeah.

MA: Yeah. Taken then for a time to a police station where I was kept for a few days and then later the German Air Force picked me up and I was taken to [pause] No, it’s gone. I’m sorry, it’s gone.

GT: So, it’s taken prisoner of war that’s, that’s a, it’s a pretty big time and in this case you’ve written quite a bit about it in your beautiful books here Maurice and I think our listeners would be, would get a great sense of, of the time you spent with them and we can let you let you know of those books. So that was, that was over a year and a, a year and a bit you were a prisoner of war. So you had many of the other British flyers with you or Americans. Or —

MA: I’m not putting it very well, am I?

DA: In the prisoner of war camp there was British wasn’t there?

MA: Sorry, I can’t —

GT: Yeah. Lots of Royal Air Force. Yeah. So, so during, when it came time for the end of the war there you were repatriated back to England. Did you fly? Did Lancasters pick you up? Or how did you get back from Europe?

DA: Oh well, you all escaped from the guards didn’t you when the war finished.

MA: We were being marched from one German prison camp to another and at the end of the war the camp in which we were was thrown open and the German guards left and we were left on our own to get back to England as best we could. We waited for a time in the camp until we were picked up by a British group who then took us to one of the local German airfields where we were put together with a lot of other American err British ex-prisoners and flown back to England.

DA: You could mention about how you went to some more and went from the camp and you commandeered that German car, and you drove to the —

MA: I don’t think it’s good.

DA: You didn’t think it‘s right.

MA: I don’t think it’s good. No. I’m sorry.

GT: So, Maurice, once you, did you demob straight away or did you stay in the RAF from that time? Yeah.

DA: You were sent home on leave weren’t you? For a month.

MA: That’s right.

DA: And every time the month was nearly up they wrote another letter and said it’s extended.

MA: And this went on for about three or four months, didn’t it?

DA: Yes. Yes.

MA: So, I was in the RAF in Britain.

DA: But at home.

MA: Taking, looking after trainees and people.

DA: And we got married.

GT: Yeah. So where did you meet Doris?

DA: Oh, we’d known each other before the war.

MA: Before the war.

DA: Yeah.

MA: Yeah.

GT: Fabulous. And did you stay? Did you go back to Redditch?

DA: Yes.

MA: Yes. And what happened? I set up a small business. A little advertising agency which also painted shop signs and things. But there seemed very little in this to go on and when the government offered university and college trainees for ex-servicemen I applied for a five year grant to study at Birmingham College of Art.

DA: And you were granted that.

MA: Which I was granted.

GT: Awesome. And you moved on and you said you took a job with a television company.

DA: That was —

GT: No.

DA: You went, after the college you went to [ Burton?] College of Art to teach.

MA: That’s right.

DA: And we stayed there, what two or three years.

MA: Yes. I began teaching at Burton.

DA: Yes.

MA: School of Art. For —

DA: Two or three years.

MA: A few years.

DA: And then we went to Newcastle on Tyne to the Art College up there. But we only stayed there about a year or less and you —

MA: Yeah.

DA: We went down to London and you took a job with Granada Television which was just opening up.

GT: Granada Television. Yes. I see you’ve got a lovely photograph here of all your crew. So, what shows did you work on? Was it television or was it movie? Or —

DA: It was more that you did the graphic designs that came —

MA: It’s in the book.

GT: Yeah. Yeah.

DA: You did the graphic designs that came up to the —

MA: And the set designs.

DA: And the set designs.

GT: Yeah.

DA: For the programmes. Yeah.

GT: Yeah. I’m going to mention for the recording now that Maurice’s book is specifically autobiography, “There’s No Caviar for a Kingfisher,” by Maurice Askew. “A scrapbook of life in a Midlands town during the years from the 20s to the early 60s,” in the RAF and then the golden years of commercial television and Maurice has detailed everything of his Royal Air Force training, career, the operations and then his POW time in that. So that is wonderfully written Maurice and it’s a great piece that we can refer people who are interested to read there from there. So, after your time with Granada you did, you, you emigrated to New Zealand then. Was it 1963 Doris? Was that right?

DA: Yes. Yes.

MA: Yes.

DA: That’s right. Yes. You saw it advertised, didn’t you? And you’d been in Granada a few years and you thought well this was another opportunity so you applied and they accepted us and arranged for us to fly out. Well, we didn’t fly. We came by boat, didn’t we?

GT: Yeah.

DA: We came out on the Gothic. Was it called the Gothic?

MA: Gothic.

DA: Yes. It had, the Queen had used that boat for one of her trips.

MA: Wow.

DA: And the company had taken it back over and they’d taken all the central heating and air cooling thing out and it was on the side of the quay and so we were very hot at times.

GT: Right. That’s fascinating. So, you, and of course you had a family and —

DA: Yes. We had the two children then. Sue was coming up to seven and Colin was three. And —

GT: Fabulous. And your daughter Susan works here in Christchurch.

DA: Yes.

GT: And your son works still in England.

DA: Yes. He has his own business. He was with Shell for many years but they moved back to Holland. He had just got married and they were buying a house and he didn’t want to go and to sell all up and go to Holland and his wife had a good job as well so they, he just resigned.

GT: Fabulous. And you’ve stayed here in Christchurch and enjoyed—

DA: Yeah.

GT: Christchurch, New Zealand ever since.

DA: Ever since. Yes.

GT: Yeah.

DA: We’ve been quite happy here.

GT: Fabulous. And recently though, 2015 you’ve been made contact with a chap from Germany, Volker Urbansky who’s found your, the crash site of your aircraft.

DA: Yes.

GT: And that was something that was rather a surprise for you, I see.

DA: It came out of the blue didn’t it, Maurice?

MA: Yes.

GT: So, you’ve had, Volker has been in contact with you quite a bit and he’s given you quite an array of information and the night you were shot down the Messerschmitt 110 pilot who shot you down was Rudolph Franck and I’m looking at a Wikipedia example of Rudolph Franck’s history and he shot down forty two or had forty two aerial victories over allied aircraft. He too was then shot down and killed later in a collision with another Lancaster. But Volker here has managed to find the impact point of where your Lancaster crashed and went in to the snow and the ice. Have you had quite a bit of contact with him, Maurice?

DA: We did at first. When he first found it.

MA: I don’t like it. The way this is going.

GT: Understood. Okay.

MA: Stop it.

GT: Well, Maurice —

MA: I like to write things down so that, you know I can alter it as I go.

GT: Sure.

MA: And —

GT: Yeah.

MA: This quick thinking has gone these days I’m afraid.

GT: Well, Maurice —

MA: Can we do it some other way?

GT: Well, certainly, well look I think Maurice —

MA: Sorry.

GT: We’ve got enough material and it’s been fascinating meeting you today Maurice and thank you very much for letting me chat with you and Doris and I certainly appreciate the sacrifice you guys made for us and thank you very much for letting me interview you for the International Bomber Command Centre. You have an amazing amount of history here of your time and I certainly do thank you for that and thank you for letting me talk with you. So, thank you. We can finish the interview now.

MA: Alright. Thank you.

GT: But is there anything you would like to say to the IBCC and, of your time or are you pretty happy to leave it at that?

MA: Not really, am I? I’ve made a mess of that.

GT: No. You did fine Maurice and I certainly thank you.

DA: It’s getting, you’re getting tired now.

MA: It, it will be a pleasure. I hope it will be a pleasure talking to you.

GT: Excellent.

MA: We’ll see. Yeah.

GT: And we also have your lovely wife Doris sitting here too.

MA: Right. Yeah.

GT: And she’s going to help us with some of the bits and pieces to fill in too. So she’s, she’s very much with it and exactly what we’re, just Maurice can you please tell me a little bit about where you grew up and why you wanted to join the Royal Air Force?

MA: I grew up in a small town in Worcestershire called Redditch and when the war broke out it was necessary for me to be in one of the services. If I didn’t volunteer for any service it would be the army. So, I didn’t fancy the army but the RAF was waiting to welcome me and I joined the RAF in [pause] when?

DA: ‘41.

MA: 1941. Yeah. 1941. Now what?

GT: And as you joined up as an engineer fitter. Aircraft technician.

MA: A flight.

GT: An aircraftsman there.

MA: Yeah. An aircraftsman.

GT: Yeah.

MA: Okay.

GT: So, you were responsible for engines and air frames.

MA: Yeah. Yeah.

GT: And from there you went, still wanted to go in the air didn’t you?

MA: I’m trying to —

GT: You wanted to become a flyer.

MA: Yes. So, I was based in —

GT: In RAF St Athan.

MA: St Athans. Yes. But after a time I felt I should be flying and so I transferred to training at Spilsby to become a flight engineer which was a step beyond a mechanic I suppose.

GT: How was that training? Did you, did you find it difficult moving from a ground job to an air job? Or was it just a simple? It was easy.

MA: No. No. It was just a straightforward move from one job to another.

GT: And, and the flight engineer job working on the aircraft as a flyer was no different you thought.

MA: I don’t know how I can put it quite. I’m sorry.

GT: Your, your experience though Maurice was what you wanted to do. You wanted to fly and you achieved that. And so, so then the moving to finding a crew. You went to Syerston, to Number 5 Lancaster Finishing School.

MA: Yes.

GT: Can you describe how you found your skipper and your crew?

MA: And then a number of flight people got together in the, in a hall where we sorted ourselves out. Pilots, flight engineers, and so on. And I’m not putting this very well.

GT: You’re doing —

MA: My wife can explain.

GT: You’re doing very well. That’s fabulous. Yeah. That’s the information we’re after. And therefore you found your skipper.

MA: My skipper. How I came —

DA: Wally Jarvis.

MA: To get the link up with Wally —

GT: Yeah.

MA: I’m not sure. We just liked one another although in a way we were quite different. Wally was a light boxer actually. I wasn’t a boxer at all. But we got on so well somehow and continued our training together as pilot and flight engineer.

GT: And you were joined by your, you joined up with a navigator and wireless operator too.

MA: And in a similar way we picked up navigators and gunners. I’m not putting this well.

GT: Yes. I’ve got, your navigator was Sid Pearson.

DA: Yes.

GT: And your wireless operator was Jeff Moray.

MA: Yes.

GT: Is that right? Yeah. And your bomb aimer was Phil Paddock.

MA: That’s right. That’s the name of our crew.

GT: Yeah. And then you had two Canadians as your gunners.

MA: Yeah.

GT: That’s great. So then you were at Spilsby.

MA: That’s right. Yes.

GT: Yeah.

MA: We went to Spilsby where we trained in various aspects of Air Force life I suppose [pause] sorry. It’s gone. It’s gone.

GT: Yeah. That’s good. That’s good. So, at Spilsby. That’s in Lincolnshire, isn’t it?

MA: Yeah.

GT: So, so you weren’t far away from the main action of all the airfields. So, you did your first operation and you were just saying to me that was Berlin, that was your first op.

MA: Yes. My first op with the crew was to Berlin.

GT: And that was about February 1944.

MA: Yes. Yeah. It all went quite well actually and we returned.

GT: It was very busy night you said in your book. There was lots of fireworks going on.

MA: Berlin, of course was a major target in those days. I just remember lots of fireworks going off. You know —

GT: And you, and you certainly managed to get back okay so that was fabulous. But, but it was, it was the next night, on your second operation of your crew on the 19th and 20th of February and you were flying in EMA for Able.

MA: Yeah.

GT: Aircraft number EE126.

MA: Yes.

GT: And your target was —

MA: Leipzig.

GT: Leipzig. Can you, can you remember what happened?

MA: We set off for Leipzig and [pause]

GT: You had some, you had a Messerschmitt 110 come at you didn’t you? Your gunners, your gunners took at them.

MA: As we, as we reached the target going in there were fireworks and so on in front of us we were attacked by a Messerschmitt.

GT: And that set you on fire so you had to get out, eh? And I see you’ve written in your book that Philip was a little bit stuck trying to get out so you gave him a bit of a push to get out. And Wally was blown out of the, out of the cockpit. So they were saved.

DA: Yes.

GT: Yeah. And what? You managed to pull your rip cord, okay.

MA: Automatically I presume. As I went out.

GT: Because you knocked yourself unconscious.

MA: And the side of the cockpit exit hatch hit me and I passed out to come around as I was just above the ground which I thought was the sea because of white waves. But suddenly as I hit the ground as it was I passed out again.

DA: It was snow.

MA: And of course, the ground had been covered. Was covered in snow at that time.

GT: And you were rescued? You were rescued then, and a family took you in and looked after you. Is that right?

MA: This is a mess. I’m sorry.

GT: Yeah. Maurice, you’re doing fine. So, so in this case though you survived the snow and you were taken prisoner of war.

MA: And picked up by some farm people who took me to their farmhouse, patched me up as best they could, gave me something strong to drink and there I stayed for two days perhaps until the RAF sent RAF police to pick me up.

DA: Well —

MA: Yeah. The German. German police.

DA: German.

MA: German police.

GT: Yeah.

MA: Yeah. Taken then for a time to a police station where I was kept for a few days and then later the German Air Force picked me up and I was taken to [pause] No, it’s gone. I’m sorry, it’s gone.

GT: So, it’s taken prisoner of war that’s, that’s a, it’s a pretty big time and in this case you’ve written quite a bit about it in your beautiful books here Maurice and I think our listeners would be, would get a great sense of, of the time you spent with them and we can let you let you know of those books. So that was, that was over a year and a, a year and a bit you were a prisoner of war. So you had many of the other British flyers with you or Americans. Or —

MA: I’m not putting it very well, am I?

DA: In the prisoner of war camp there was British wasn’t there?

MA: Sorry, I can’t —

GT: Yeah. Lots of Royal Air Force. Yeah. So, so during, when it came time for the end of the war there you were repatriated back to England. Did you fly? Did Lancasters pick you up? Or how did you get back from Europe?

DA: Oh well, you all escaped from the guards didn’t you when the war finished.

MA: We were being marched from one German prison camp to another and at the end of the war the camp in which we were was thrown open and the German guards left and we were left on our own to get back to England as best we could. We waited for a time in the camp until we were picked up by a British group who then took us to one of the local German airfields where we were put together with a lot of other American err British ex-prisoners and flown back to England.

DA: You could mention about how you went to some more and went from the camp and you commandeered that German car, and you drove to the —

MA: I don’t think it’s good.

DA: You didn’t think it‘s right.

MA: I don’t think it’s good. No. I’m sorry.

GT: So, Maurice, once you, did you demob straight away or did you stay in the RAF from that time? Yeah.

DA: You were sent home on leave weren’t you? For a month.

MA: That’s right.

DA: And every time the month was nearly up they wrote another letter and said it’s extended.

MA: And this went on for about three or four months, didn’t it?

DA: Yes. Yes.

MA: So, I was in the RAF in Britain.

DA: But at home.

MA: Taking, looking after trainees and people.

DA: And we got married.

GT: Yeah. So where did you meet Doris?

DA: Oh, we’d known each other before the war.

MA: Before the war.

DA: Yeah.

MA: Yeah.

GT: Fabulous. And did you stay? Did you go back to Redditch?

DA: Yes.

MA: Yes. And what happened? I set up a small business. A little advertising agency which also painted shop signs and things. But there seemed very little in this to go on and when the government offered university and college trainees for ex-servicemen I applied for a five year grant to study at Birmingham College of Art.

DA: And you were granted that.

MA: Which I was granted.

GT: Awesome. And you moved on and you said you took a job with a television company.

DA: That was —

GT: No.

DA: You went, after the college you went to [ Burton?] College of Art to teach.

MA: That’s right.

DA: And we stayed there, what two or three years.

MA: Yes. I began teaching at Burton.

DA: Yes.

MA: School of Art. For —

DA: Two or three years.

MA: A few years.

DA: And then we went to Newcastle on Tyne to the Art College up there. But we only stayed there about a year or less and you —

MA: Yeah.

DA: We went down to London and you took a job with Granada Television which was just opening up.

GT: Granada Television. Yes. I see you’ve got a lovely photograph here of all your crew. So, what shows did you work on? Was it television or was it movie? Or —

DA: It was more that you did the graphic designs that came —

MA: It’s in the book.

GT: Yeah. Yeah.

DA: You did the graphic designs that came up to the —

MA: And the set designs.

DA: And the set designs.

GT: Yeah.

DA: For the programmes. Yeah.

GT: Yeah. I’m going to mention for the recording now that Maurice’s book is specifically autobiography, “There’s No Caviar for a Kingfisher,” by Maurice Askew. “A scrapbook of life in a Midlands town during the years from the 20s to the early 60s,” in the RAF and then the golden years of commercial television and Maurice has detailed everything of his Royal Air Force training, career, the operations and then his POW time in that. So that is wonderfully written Maurice and it’s a great piece that we can refer people who are interested to read there from there. So, after your time with Granada you did, you, you emigrated to New Zealand then. Was it 1963 Doris? Was that right?

DA: Yes. Yes.

MA: Yes.

DA: That’s right. Yes. You saw it advertised, didn’t you? And you’d been in Granada a few years and you thought well this was another opportunity so you applied and they accepted us and arranged for us to fly out. Well, we didn’t fly. We came by boat, didn’t we?

GT: Yeah.

DA: We came out on the Gothic. Was it called the Gothic?

MA: Gothic.

DA: Yes. It had, the Queen had used that boat for one of her trips.

MA: Wow.

DA: And the company had taken it back over and they’d taken all the central heating and air cooling thing out and it was on the side of the quay and so we were very hot at times.

GT: Right. That’s fascinating. So, you, and of course you had a family and —

DA: Yes. We had the two children then. Sue was coming up to seven and Colin was three. And —

GT: Fabulous. And your daughter Susan works here in Christchurch.

DA: Yes.

GT: And your son works still in England.

DA: Yes. He has his own business. He was with Shell for many years but they moved back to Holland. He had just got married and they were buying a house and he didn’t want to go and to sell all up and go to Holland and his wife had a good job as well so they, he just resigned.

GT: Fabulous. And you’ve stayed here in Christchurch and enjoyed—

DA: Yeah.

GT: Christchurch, New Zealand ever since.

DA: Ever since. Yes.

GT: Yeah.

DA: We’ve been quite happy here.

GT: Fabulous. And recently though, 2015 you’ve been made contact with a chap from Germany, Volker Urbansky who’s found your, the crash site of your aircraft.

DA: Yes.

GT: And that was something that was rather a surprise for you, I see.

DA: It came out of the blue didn’t it, Maurice?

MA: Yes.

GT: So, you’ve had, Volker has been in contact with you quite a bit and he’s given you quite an array of information and the night you were shot down the Messerschmitt 110 pilot who shot you down was Rudolph Franck and I’m looking at a Wikipedia example of Rudolph Franck’s history and he shot down forty two or had forty two aerial victories over allied aircraft. He too was then shot down and killed later in a collision with another Lancaster. But Volker here has managed to find the impact point of where your Lancaster crashed and went in to the snow and the ice. Have you had quite a bit of contact with him, Maurice?

DA: We did at first. When he first found it.

MA: I don’t like it. The way this is going.

GT: Understood. Okay.

MA: Stop it.

GT: Well, Maurice —

MA: I like to write things down so that, you know I can alter it as I go.

GT: Sure.

MA: And —

GT: Yeah.

MA: This quick thinking has gone these days I’m afraid.

GT: Well, Maurice —

MA: Can we do it some other way?

GT: Well, certainly, well look I think Maurice —

MA: Sorry.

GT: We’ve got enough material and it’s been fascinating meeting you today Maurice and thank you very much for letting me chat with you and Doris and I certainly appreciate the sacrifice you guys made for us and thank you very much for letting me interview you for the International Bomber Command Centre. You have an amazing amount of history here of your time and I certainly do thank you for that and thank you for letting me talk with you. So, thank you. We can finish the interview now.

MA: Alright. Thank you.

GT: But is there anything you would like to say to the IBCC and, of your time or are you pretty happy to leave it at that?

MA: Not really, am I? I’ve made a mess of that.

GT: No. You did fine Maurice and I certainly thank you.

DA: It’s getting, you’re getting tired now.

Collection

Citation

Glen Turner, “Interview with Maurice Vivian Askew,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 27, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/10079.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.