Interview with Syd Grimes

Title

Interview with Syd Grimes

Description

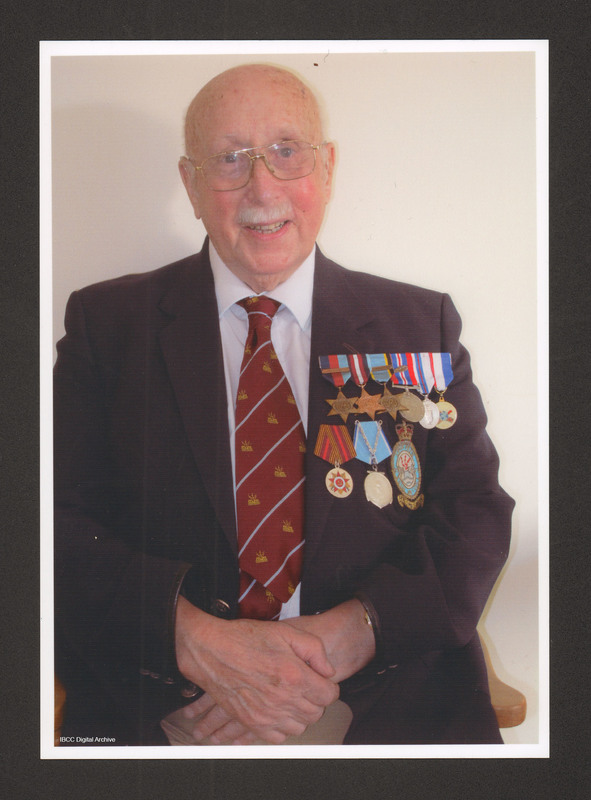

Sydney Grimes grew up near Southend and joined the RAF as a wireless operator in 1940. He flew a total of 41 operations - 24 with 106 Squadron and 17 with 617 Squadron. He then served on 9 Squadron at RAF Bardney for 2 months and, subsequently, with 50 Squadron at RAF Sturgate for 3 months, where he assisted on the return of prisoners of war in Operation Dodge. After demobilisation he returned to his old company and retired as the managing director.

Creator

Date

2015-11-21

Language

Type

Format

00:54:01 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Identifier

AGrimesS151121

Transcription

SJ: This interview is being conducted for the International Bomber Command Centre. The interviewer is myself Sue Johnstone and the interviewee is Sid Grimes. The interview is taking place at Mr Grimes’ home in Mildenhall in Suffolk on the 21st of November 2015.

AG: I was born in a little village called Great Wakering near Southend on Sea, five miles from Southend on Sea and I lived there until I joined the Air Force. I was educated at the village school and also for part of the time at Southend Municipal College. When war broke out I was seventeen and eh my father was a Thames bargeman. I didn’t particularly want to go in the Navy although he would have preferred me to. My my brother went in the Navy, I didn’t want to go in the Army and I thought if I go in the Air Force and volunteered as a wireless operator. At that time I was working for EK Cole Ltd,Echo Radio and I thought if I knew something about the technology of radio I would be doing a more interesting job than as a clerk. So I joined the Air Force. I wasn’t accepted for training immediately because there was a real backlog of training. But I volunteered for wireless operator aircrew and I was called up in 1940. I trained at Blackpool, Yatesbury, Eventon,Madeley and all sorts of places as wireless operator. Eventually I ended up as a sergeant wireless operator at Cottesmore in Rutland. ‘Is this alright?’

SJ: This is absolutely fine, this is fantastic.

AG: Eh, I then met my first pilot a man called Stevens, a Welshman always known as Steve eh and the four others of the crew, so. And eh we trained on Wellingtons until he was eh, he was,treated as a bomber pilot then. We then moved to a conversion unit where we flew Manchesters and Lancasters. Having passed out then we went to a place called Syerston near Newark. Now this 106 Squadron was Guy Gibsons’ Squadron, but he must have known that I was coming because he left the two days before. [laughs] No I don’t know if it was two days but a few days before. So I joined 617 Squadron [think he meant 106] and by that time we had picked up a mid upper gunner and a flight engineer, to the Wellington crew so we were now seven. And I did a tour with 106 Squadron until September 1943. Now that was almost entirely the Battle of the Ruhr. but it did include places like Hamburg and Berlin, one or two other places just outside the Ruhr. So having completed a tour of operations which was a real dodgy period. We had some very heavy losses in the Battle of the Ruhr. In fact my crew was only the second one to finish a tour while I was there. And a lot of people came and went fairly quickly so. I do not know how many losses 617, 106 Squadron had in that period. But we were only the second one to finish. I then went to a place called Balderton just outside Newark which was eh, the residue of the Five Lancaster Finishing School, Five Group Lancaster Finishing School. And eh an interesting thing happened to me there because we hadn’t got any pupils to train then, they were coming in a couple of weeks time and we were getting the place ready. A wing commander arrived, Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire and eh he had been operating in Four Group up in Yorkshire on Halifax’s. And when he came to take over 617 Squadron the AOC said, ‘you had better go and learn to fly a Lancaster.’ So he eh hummed and had and said. ‘Well I have been flying Halifaxs for two years.’ But he said ‘No you go and learn it.’ So he came, he hadn’t got a clue so I went with him and four others. And we became, and I am very proud to tell you, I have in my log book. Four times I flew with him while he learnt to fly a Lancaster. [laugh]. I then went from there to the permanent base for Five Lancaster School of eh, Lancaster Group, School at Syerston again. And I stayed there instructing until I done a foolish thing. I was engaged to be married and I saw in orders that there was a course for RT speech unit, at Stanmore. And I thought if I went to Stanmore, Iris was nursing at Leightonstone, Whipps Cross Hospital, Leightonstone. I would undoubtedly get a couple of days before I reported back. So I did this RT speech course, but I was quite good at it actually and of the six of us I got chosen to form this RT speech unit.

SJ: Brilliant.

AG: At Scampton, so I went there and very foolishly I had to do the same lecture four times a day seven days a week.

SJ: How’s that?

AG: And I met a man called Barney Gumbley, a New Zealander and we sat chat. Chatting in the mess one day and he said. ‘I am going back on ops, are you interested?’ I said. ‘Can we go tomorrow?’ [laugh]. So he said. ‘Well I have got an interview for Pathfinders and an interview for 617 have you any preference?’ I said was, Pathfinders was Eight Group and eh I quite like Five Group, I like the people in it. So I said ‘I’d rather go to 617.’ He said ‘It is a good job you said that, for the rest of us want to go there too.’ [laugh]. Anyway about ten days later I got a phone call to say. ‘There is a van picking you up at nine o’clock tomorrow morning.’ I said. ‘Where are we going?’ He said. ‘We are going to Woodhall Spa to joing 617 Squadron.’ So of I went in this van and eh the mess, the Officers Mess, was eh ‘oh dear, oh dear’ I can’t think of it.

SJ: What Woodhall Spa?

AG: At Woodhall Spa, it was the Officers Mess eh.

SJ: Was it the Petwood?

AG: Petwood.

SJ: Petwood Hotel.

AG: Petwood hotel and eh it dropped me there and I reported at the desk which had, [unclear] which had got a WAAF on it. And she said ‘Oh yes we’ve got a room for you.’ So of I went to this room, Barney Gumley was told I was here but he was up at the flight which was about a mile and a half away. He came down and introduced me to the rest of the crew, but no one thought about booking me in.[laugh]. And I did the two ops to the Tirpitz at Tromso before they suddenly realised I wasn’t on the squadron. [laugh] By that time I had done two trips.

SJ: Then they checked you in.

AG: They checked me in they thought I had better be legitimate. So I, I was with 617 from the September ’44 through ‘til April 1945. We had been flying the Barnes Wallis Tall Boy bomb which was 12000 pounds. And then he came up with a much bigger invention, the Grand Slam which was 22000 pounds. In order to accommodate the big bomb they had to take the bomb doors off, and they took the mid upper turret off, and they took all the armour plating out. They really did a modified Lancaster which only took a crew of five. Took all the wireless equipment out except for a VHF transmitter,RT. So I was surplus so I said to the flight commander. ‘ I have only got three more trips to do can I fly in the astrodome as a fighter observer or something like that?’ He said. ‘Under no circumstances, we are trying to find reasons for loosing weight.’ And he said. ‘You want to go and fly.’ He wouldn’t let me and the crew got shot down on the very next trip. So they got hit by and anti aircraft shell on the port wing and it shot it completely away. So they were on the bombing run at that time which was the dicey part of the trip. Because eh, the special bomb sight that we had, we had to fly straight and level. It was gyroscopically controlled, so you had to fly very accurately with height, speed and all the outside temperatures. And all that kind of thing which you fed in to this computer. So they was, the squadron flew in what was called a gaggle. A geese gaggle you know? The way that they fly in the sky.

SJ: A formation.

AG: A formation, and that gaggle when you were stepped sideways and up and down in a very large box. It was designed so that the whole squadron, twenty of us could bomb without impeding each other, all on the same bombing run. You were actually converging you see, so all the bombs had gone before you actually hit each other. It was a very clever little devise and this anti aircraft shell shot their port wing off so that it. It just spiralled in [unclear], and it was spiralling so quickly, if anybody was still alive in the aircraft eh they couldn’t have got out anyway. And of course the bomb went off as soon as it hit the ground. Because as they were on the bombing run the bomb aimer had already fused it.

SJ: Eh, you don’t remember which aircraft it was?

AG: Yes it is in, I flew with them. ‘Just sit down my dear.’ You can put it off for a bit.

SJ: I was going to pause it for a second.

AG: YZL, PD117 The number of the aircraft was PD117.[pause]

SJ: That looks like a well looked through log book.

AG: Just to prove Wing Commander Cheshire.

SJ: Yes that’s where he had gone to. That is local flying that was part of his training. [laugh]

AG: That’s right, I always say that he was my pupil.

SJ: [laugh] that’s brilliant. So what happened next, you were moved to 617 you were there for a six months.

AG: Yes and I done seventeen trips.

SJ: Seventeen trips.

AG: I got three more to do.[pause] ‘I will just have a cough sweet.’

SJ: That is no problem, that’s fine.

AG: [pause while uwrapping sweet] ‘Will you stay for some lunch?’

SJ: Oh, might do if that’s all right, yeah.

AG: I have got a beef casserole.

SJ: Lovely, that sounds fantastic.

AG: Right, I will heat it up in a minute.

SJ: [Laughs]

AG: ‘Sorry, I was, what was I saying —.

SJ: You were saying about 617 Squadron when you left.

AG: Yes I went to 9 Squadron who was the other squadron that had the tallboys, they didn’t have the grand slam, so that they still needed wireless operators. So I went over to 9 Squadron about three weeks before the end of the war. After we, I then had to make a decision, I was asked did I want to go to the far east against Japan. By that time I was married.

SJ: When did you get married?

AG: I got married the month before I joined 617, Iris never knew I had volunteered to go back.

SJ: Did you ever tell her.

AG: I have since, she was indignant. [laugh]. But I always said she was in a more dangerous situation as a nurse in Whipps Cross Hospital near the docks.

SJ: Was she always a nurse then?

AG: I didn’t say how I met her, did I?

SJ: You didn’t no.

AG: Can I digress?

SJ: Yes that will be fantastic to know.

AG: She was born in Woodford. But before the war they moved down to a little village called Rochford just outside Southend. And she wanted to be a nurse but they wouldn’t take her until she was seventeen. So she came to Echo as a copy typist. I was one of the senior, not senior clerks but I was, I was fairly well up. I had been there three years. And I met her and I liked the look of her and so after I went in the Air Force I kept in touch with her. And you know, I’d spent about no more than about ten days in her company, up to the time we got married. Because when I came on leave we always went to see a London show but that was about the only time we could get of. ’Forgive me sucking the sweet.’

SJ: Oh no it’s fine, not to worry.

AG: And that is how I met her. So I decided I didn’t want to go to the Far East I thought that having done about forty six trips, I didn’t , the neck had gone out too far. So I got posted to 50 Squadron at a place called Sturgate which was up near, in North Lincolnshire. And we were then flying; first of all we were flying prisoners of war from Brussels to England, in the Lancasters. We used to take, I think it was twenty or twenty four depending on what kit they got in the Lancaster fuselage sitting on the floor But they didn’t mind that as long as they were coming to England. After we got all the POWs back we then started bringing people back from leave from Italy. And we used to fly to Naples and pick up about twenty Air Force or Army people at a place call Pernicano, which is just outside Naples. Eh after a time they decided that was going to stop because shipping was available to bring them back in larger quantities anyway. And the Mediterranean was open so they stopped doing it. So I then got posted to do a code and cipher course down at a place called Compton Bassett near Calne in Wiltshire. And having passed that course I got posted to Germany ostensibly to be the CO of a small mobile signals unit. Which was one officer, one sergeant, one corporal and about ten men. When I got there I was told it was based at a place called Stade[?] between Cookshaven and Haverg. So I arrived at Stade[?] and the CO said. ‘Oh I am glad to see you’ he said. ‘I lost my adjutant about two weeks ago you are my new adjutant.’ I said. ‘No I have a mobile signals regiment.’ He said. ‘No I closed that down yesterday and you are my new adjutant.’ But I said. ‘I know something about flying but I know nothing about anything else.’ He said. ‘I’ll teach you.’[laugh] and he became a very good friend of mine. We did all sorts of things together, we got up very early in the morning sometimes at dawn and went and shoot deer. Quite unofficial we hadn’t got a license from the Military Government or anything and it ended up in a very humorous story. We had this, there weren’t very many of us, these base signals on your radar unit, refurbished these units to be sent round to the aerodromes and various places including Berlin. So there were only about fifteen of us I suppose. And we were having dinner or preparing to have dinner one night and we had got deer for dinner. This happened, Military Government people and ourselves we didn’t mingle sociably ‘cause there was nothing else. So they arrived about four o’clock and didn’t look like moving. So the CO said to me ‘What do we do?’ I said ‘Well as they are the guests of our mess this evening you had better invite them to dinner. And as they are our guests they won’t be able to do anything about it.’ So they sat down to dinner with us and ate deer. And they did let us know that they were aware of it. I think they had been told off, they had a [unclear] [laugh]. Well that, I ended up demobilised in August 1946 and I got reinstatement rights if I went back to Echo, but I was offered a short service commission of two years. But if I had taken that it would have meant in all probability the Air Force would have been reducing in size so much that I would have then been demobilised. And I wouldn’t have had reinstatement rights, having been in what was the regular Air Force for two years. So eh I went back to Echo. And so as I say I didn’t know anything about being an adjutant and certainly nothing about earning my living in civvy street. But I was fortunate, the man who interviewed me was the deputy chief accountant of EK Cole Ltd. And he knew because I had told him that I was keen on cricket because he was interviewing me in depth. He said ‘That’s a good thing I am a life member of Lancashire.’ So he took me on his staff and he taught me accountancy. I did take a correspondence course was meeker compared with what he told me. So I was never able to be a chartered accountant because I didn’t take articles. I was earning my living, by that time I was increasing my family.

SJ: How many children have you got?

AG: I’ve got three, two of them became nurses and one, the boy went into insurance.

SJ: You had two girls and a boy.

AG: I am proud of them all.

SJ: Oh yeah I don’t blame you.

AG: So I was in the deputy chief accountants department. Then he got promoted to be the chief accountant and then he became promoted to eh; financial secretary and accountant to a number of subsidiaries. So as he went up my situation went up with him.

SJ: You went up as well, did you enjoy that?

AG: I couldn’t have been an accountant in a professional office because that would have been dull. That would have been checking, checking, checking, checking. What I liked about being in industry, I was always in a place that was making things and you could go there and see it all happening. It was accountancy, it was very important accountancy, but eh —.

SJ: Very different from your RAF days though?

AG: Yes very much so. I was an active member of the 617 Squadron Association and we went to a number of reunions in Canada, Australia, New Zealand eh France as a unit, we’ve gone and made friends wherever we went. I haven’t been to the last couple number of places because Iris became, eh unreliable, she was unsteady. I couldn’t take her onto aircraft and coaches and things like that. She came to, she came to Australia and New Zealand and to Canada but the —, When we went to France and Germany and the Netherlands we went by coach and ferry, she hates flying.

SJ: [laughs]

AG: ‘Now where have I got to?’ Eventually we got taken over, first by Pye from Cambridge and then Phillips who are Dutch of course. But the British office was at Croydon and eh I became the financial accountant, financial director in a number of subsidiaries around the group. But I ended up, I always wanted to be somewhere near Southend because my parents were still alive. And I owed a lot to my parents, I didn’t want to move right out of their orbit. And I then went to Canvey Island to a components factory. First of all as the financial director and then as the managing director. And from there I went back to Southend as the eh; managing director of Echo Instruments which made instrumentation for industry. Then I retired.

SJ: How long have you been retired now?

AG: I retired when I was, I retired finally when I was sixty three. I first retired at sixty one when I left Canvey. And I only had been retired for about three months when my boss at Cambridge rang me up and said. ‘I am in trouble, can you help me?’ I said. ‘Well, help you in what sense?’ He said. ‘Can you come back and do a job looking after a subsidiary until I find a, a permanent managing director?’ So I did and I stayed two years.

SJ: [laugh] Why not?

AG: But it was a good period for me because I was drawing full pension and then I was drawing full salary so it made a nest egg for me when I did retire.

SJ: So it was worth it then?

AG: Yes; well I stayed in Shoeburyness just outside Southend until twelve years ago. But one of my daughters lived in West Row which is just to the West of Milden Hall and another one lived in Barton Mills.

SJ: I was going to ask why you moved up this way?

AG: Well my son was in Kent and the journey from Shoeburyness up to here was one hundred and ten miles. And when I got to eighty I decided that that was too far. So we moved up here to a place just the other side of Mildenhall, Brickcone Hall[?] and eh, it was too large but we loved it. And then Iris had trouble keeping her balance, damaged her hip. So I decided we had to be on the same floor so we moved here. Which was a retirement bungalow which suited us down to the ground.

SJ: And it is a lovely complex, it really is nice.

AG: It is, I sit here and we have mallard ducks and swans on the river and I watch them and they come and look at me and squawk.

SJ: [laugh] And you sit and look at them?

AG: I try, I do, if Iris was here with me I’d love it. But she is only two miles away.

SJ: That is not far. How long has she been in the care home?

AG: Since January, so eleven months. But she is happy there and she is safe. You see I had her home here at first after she came out of hospital eh, but I couldn’t look after her during the day and the night. And I was getting totally exhausted because every time she moved I woke up. So we decided that my savings would go to the wall and I would put her in the care home. And she is in a lovely little care home. She is well cared for and she is safe, so —.

SJ: Does she like it there?

AG: At first she missed us all because she saw the family every day. Well now I go in about five days out of the seven and the two girls go once. Because Rosalind is a practice nurse in Bury so ,

SJ: That is not far away?

AG: No. And she is married to a Canadian who eh and they go backwards and forwards. I think they have a permanent passage booked on aircraft [laugh]. And eh Jill has got four sons and five grandsons, my great grandsons, so we are largely together. And my son comes up —.

SJ: He is the link end.

AG: Yes. He comes up for a week about every six weeks, because he has retired now.

SJ: Has he got any family?

AG: No; he married a lady who was seven years older than him and it never happened, so —.

SJ: That is quite a big family you got then, grandkids and great grandkids.

AG: Yes, I am a very lucky man. Having survived the war I look round and think, ‘This family wouldn’t have survived if I had bought it.’

SJ: I know, yeah.

AG: Well they might have done, Iris might have married someone else, but.

SJ: It would have been different though.

AG: They wouldn’t have had my genes.

SJ: No exactly [laugh]

AG: I’ll heat the —.

SJ: I shall put this on pause shall I?

AG: Since I retired, lived in Shoeburyness, Mildenhall and here there has been a resurgent of interest in 617. And also strangely in Pye Cambridge. And I have been recruited, to say to do this kind of interview for Pye Cambridge. Because they are making a record of the activities of Pye in Cambridge, because it has been there ever since it was formed.

SJ: So they are getting a history together of that part of Pye?

AG: There is a historical museum which is bringing all these records together. So they are doing what you are doing and making recordings and eh —.

SJ: It is great it needs doing. I mean how do you feel about the project? How do you feel about the Bomber Command Archive project?

AG: Lets say this. After I have had a session like this or with John Nichol . Or with other things the squadron seems to send to me. Eh, like the Cambridge stamp centre and signing things happened. Undoubtedly I have a disturbed couple of nights. Because it has brought it all back. But then the family encourage me and I totally accept the fact, if people like me didn’t say what this was like. The written word is not necessarily understood. But I think if they hear peoples voice as you are doing now, it might stop wars happening. I thank my lucky stars, that my son didn’t ever have to go through the trauma of a six years war. It was, don’t get me wrong. I think it was necessary. Hitler wouldn’t have got stopped in any other way. And I think in a way Hitler getting stopped, Mussolini and Stalin also got stopped. Because the consequences of the nuclear bomb was so dreadful that it stopped. And I don’t think there would have been a nuclear bomb if it hadn’t have been for the war, ‘cause the money would not have been found.

SJ: Yeah.

AG: Do I sound too serious?

SJ: No. I completely agree with you. Lessons need to be learnt from the past, don’t they?

AG: I think those of us who went through it. Have kind of a duty to make sure these subsequent generations knew what it was like.

SJ: Do you feel this generation and future generations will understand how it was?

AG: It’s difficult to say. But John Nichol tells me his book had a huge print and he has sold a lot of copies. So that if it get put into houses and families and people must have been buying it to read at home. It didn’t all go to libraries.

SJ: No not at all.

AG: The younger people eh, might well have learnt from it. And the BBC have done a number of programmes about the Air Force and the war in general. The Navy, all those aspects have been fired[?] some of it must have sunk in.

SJ: Yes you would like to think so.

AG: Yeah. And I think we have a duty to make sure that it became available. But it is not something that I enjoy.

SJ: Yes I completely understand, yeah.

AG: Because, well my family were fortunate. My brother was in the Navy, he was on the Arctic Convoys on HMS London, and eh —.

SJ: What was your brothers’ name?

AG: Kenneth, Kenneth George. And he, he went in the Navy. Largely because of my father I think. My father was Thames Bargeman. There’s Thames barges on the wall.

SJ: Yeah, I noticed them when I came in, yeah.

AG: My father was a Freeman of the River Thames. And he was on Thames barges and then on Thames tugs.

SJ: Did your father have military background?

AG: No, in the First World War he was a barge captain. And he, he used to load ammunition at Woolwich Arsenal, and take it over to France to a place called St Valerie.

SJ: He had a very important job.

AG: He used to take it across the channel. Through all those minefields and what have you.

SJ: Very risky.

AG: Yes it was. And at the end of the war he was presented with the Maritime Medal.

SJ: Oh brilliant.

AG: But you know the chances that he took as a civilian. He should have got much more than that.

SJ: I know. What was you fathers name?

AG: George, George David. He lived until he was ninety four, the last six years with us at Shoebury.

SJ: You mentioned your brother. Did you have any more brothers or sisters?

AG: No just the brother. My mother had twins which were still born, my brother and I —. They really were, they were extremely poor in a sense. Because in the shipping slump of 1931, 32 the barges were laid up all over the East Coast. And he just got on care and maintenance pay which was hardly anything. And with that he was trying to run himself on the barge, tied up to a buoy and the family at home. So his savings gradually went. So he had to, he had a break down eventually about 1934. And he stayed on the water in a sense because he became the hand in an oyster dredger on the river Roch at Rochford. And he did that eh, about eight months in the year. Then he was unemployed for the rest of the year. So he dispersed his savings looking after his family really. So I did have a very big moral obligation to my parents who were the salt of the earth.

SJ: Yes they sound like they were, which was great. I think that generation they were, weren’t they?

AG: They were family minded.

SJ: They were mm.

AG: They, [pause] I don’t think they bought themselves a Christmas present. Where my brother and I always had one.

SJ: Yeah, what were your family Christmases like?

AG: The family, my father had one, two, three. Three daughters, three sisters and two brothers. And one of the aunts was a school teacher and she took a fatherly interest. So silly isn’t it, she was an aunt, she couldn’t take a fatherly interest [laugh]. An aunt interest in my brother and I. And he won an open scholarship, a total scholarship to Clarks College when he was thirteen.

SJ: Oh brilliant.

AG: It was the only one on offer in the whole of the area, and he won it. He went to Clarks College. By the time I got to and I was four years younger. By the time I got to the age when I was sitting exams. They couldn’t afford for me to be another drain on the family finances. So eh, I went to work at Ecko.

SJ: How old were you when you started there?

AG: I was fourteen.

SJ: Fourteen mmm. How did you feel about working, starting work so young?

AG: It was the common thing.

SJ: It was mmm.

AG: I was on the, I was at the village and I stayed at the village. I was only at the municipal college for a short time and I was working and doing it evenings. But the village, I was almost. Hardly any of us did further education but my family believed in it. So I did further education and my brother was good example to me that he had won an open scholarship.

SJ: That was brilliant.

AG: But the village had a tradition of going to work at fourteen.

SJ: Yeah. But they did didn’t they? I mean they is eighteen now when they leave school. It is a big difference these days.

AG: But I would say this about the great working school; it was first class. And they had dedicated people. We had two Welshmen who were school masters there and they gave up their Saturdays for sport. They never let us go to a fixture without one of them being there. You know it was —. After school they’d, we would go into the playground and get a matting wicket and play cricket. And they always did it in a —. I look at teachers these days and I think to myself. ‘You should have lived with those people, you would have learned an awful lot.’ They believed in the welfare of their students. Where as now they seem to want —. [Interruption]. ‘Come in.’ [shout]

SJ: Shall I put this on?

AG: I was born in a little village called Great Wakering near Southend on Sea, five miles from Southend on Sea and I lived there until I joined the Air Force. I was educated at the village school and also for part of the time at Southend Municipal College. When war broke out I was seventeen and eh my father was a Thames bargeman. I didn’t particularly want to go in the Navy although he would have preferred me to. My my brother went in the Navy, I didn’t want to go in the Army and I thought if I go in the Air Force and volunteered as a wireless operator. At that time I was working for EK Cole Ltd,Echo Radio and I thought if I knew something about the technology of radio I would be doing a more interesting job than as a clerk. So I joined the Air Force. I wasn’t accepted for training immediately because there was a real backlog of training. But I volunteered for wireless operator aircrew and I was called up in 1940. I trained at Blackpool, Yatesbury, Eventon,Madeley and all sorts of places as wireless operator. Eventually I ended up as a sergeant wireless operator at Cottesmore in Rutland. ‘Is this alright?’

SJ: This is absolutely fine, this is fantastic.

AG: Eh, I then met my first pilot a man called Stevens, a Welshman always known as Steve eh and the four others of the crew, so. And eh we trained on Wellingtons until he was eh, he was,treated as a bomber pilot then. We then moved to a conversion unit where we flew Manchesters and Lancasters. Having passed out then we went to a place called Syerston near Newark. Now this 106 Squadron was Guy Gibsons’ Squadron, but he must have known that I was coming because he left the two days before. [laughs] No I don’t know if it was two days but a few days before. So I joined 617 Squadron [think he meant 106] and by that time we had picked up a mid upper gunner and a flight engineer, to the Wellington crew so we were now seven. And I did a tour with 106 Squadron until September 1943. Now that was almost entirely the Battle of the Ruhr. but it did include places like Hamburg and Berlin, one or two other places just outside the Ruhr. So having completed a tour of operations which was a real dodgy period. We had some very heavy losses in the Battle of the Ruhr. In fact my crew was only the second one to finish a tour while I was there. And a lot of people came and went fairly quickly so. I do not know how many losses 617, 106 Squadron had in that period. But we were only the second one to finish. I then went to a place called Balderton just outside Newark which was eh, the residue of the Five Lancaster Finishing School, Five Group Lancaster Finishing School. And eh an interesting thing happened to me there because we hadn’t got any pupils to train then, they were coming in a couple of weeks time and we were getting the place ready. A wing commander arrived, Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire and eh he had been operating in Four Group up in Yorkshire on Halifax’s. And when he came to take over 617 Squadron the AOC said, ‘you had better go and learn to fly a Lancaster.’ So he eh hummed and had and said. ‘Well I have been flying Halifaxs for two years.’ But he said ‘No you go and learn it.’ So he came, he hadn’t got a clue so I went with him and four others. And we became, and I am very proud to tell you, I have in my log book. Four times I flew with him while he learnt to fly a Lancaster. [laugh]. I then went from there to the permanent base for Five Lancaster School of eh, Lancaster Group, School at Syerston again. And I stayed there instructing until I done a foolish thing. I was engaged to be married and I saw in orders that there was a course for RT speech unit, at Stanmore. And I thought if I went to Stanmore, Iris was nursing at Leightonstone, Whipps Cross Hospital, Leightonstone. I would undoubtedly get a couple of days before I reported back. So I did this RT speech course, but I was quite good at it actually and of the six of us I got chosen to form this RT speech unit.

SJ: Brilliant.

AG: At Scampton, so I went there and very foolishly I had to do the same lecture four times a day seven days a week.

SJ: How’s that?

AG: And I met a man called Barney Gumbley, a New Zealander and we sat chat. Chatting in the mess one day and he said. ‘I am going back on ops, are you interested?’ I said. ‘Can we go tomorrow?’ [laugh]. So he said. ‘Well I have got an interview for Pathfinders and an interview for 617 have you any preference?’ I said was, Pathfinders was Eight Group and eh I quite like Five Group, I like the people in it. So I said ‘I’d rather go to 617.’ He said ‘It is a good job you said that, for the rest of us want to go there too.’ [laugh]. Anyway about ten days later I got a phone call to say. ‘There is a van picking you up at nine o’clock tomorrow morning.’ I said. ‘Where are we going?’ He said. ‘We are going to Woodhall Spa to joing 617 Squadron.’ So of I went in this van and eh the mess, the Officers Mess, was eh ‘oh dear, oh dear’ I can’t think of it.

SJ: What Woodhall Spa?

AG: At Woodhall Spa, it was the Officers Mess eh.

SJ: Was it the Petwood?

AG: Petwood.

SJ: Petwood Hotel.

AG: Petwood hotel and eh it dropped me there and I reported at the desk which had, [unclear] which had got a WAAF on it. And she said ‘Oh yes we’ve got a room for you.’ So of I went to this room, Barney Gumley was told I was here but he was up at the flight which was about a mile and a half away. He came down and introduced me to the rest of the crew, but no one thought about booking me in.[laugh]. And I did the two ops to the Tirpitz at Tromso before they suddenly realised I wasn’t on the squadron. [laugh] By that time I had done two trips.

SJ: Then they checked you in.

AG: They checked me in they thought I had better be legitimate. So I, I was with 617 from the September ’44 through ‘til April 1945. We had been flying the Barnes Wallis Tall Boy bomb which was 12000 pounds. And then he came up with a much bigger invention, the Grand Slam which was 22000 pounds. In order to accommodate the big bomb they had to take the bomb doors off, and they took the mid upper turret off, and they took all the armour plating out. They really did a modified Lancaster which only took a crew of five. Took all the wireless equipment out except for a VHF transmitter,RT. So I was surplus so I said to the flight commander. ‘ I have only got three more trips to do can I fly in the astrodome as a fighter observer or something like that?’ He said. ‘Under no circumstances, we are trying to find reasons for loosing weight.’ And he said. ‘You want to go and fly.’ He wouldn’t let me and the crew got shot down on the very next trip. So they got hit by and anti aircraft shell on the port wing and it shot it completely away. So they were on the bombing run at that time which was the dicey part of the trip. Because eh, the special bomb sight that we had, we had to fly straight and level. It was gyroscopically controlled, so you had to fly very accurately with height, speed and all the outside temperatures. And all that kind of thing which you fed in to this computer. So they was, the squadron flew in what was called a gaggle. A geese gaggle you know? The way that they fly in the sky.

SJ: A formation.

AG: A formation, and that gaggle when you were stepped sideways and up and down in a very large box. It was designed so that the whole squadron, twenty of us could bomb without impeding each other, all on the same bombing run. You were actually converging you see, so all the bombs had gone before you actually hit each other. It was a very clever little devise and this anti aircraft shell shot their port wing off so that it. It just spiralled in [unclear], and it was spiralling so quickly, if anybody was still alive in the aircraft eh they couldn’t have got out anyway. And of course the bomb went off as soon as it hit the ground. Because as they were on the bombing run the bomb aimer had already fused it.

SJ: Eh, you don’t remember which aircraft it was?

AG: Yes it is in, I flew with them. ‘Just sit down my dear.’ You can put it off for a bit.

SJ: I was going to pause it for a second.

AG: YZL, PD117 The number of the aircraft was PD117.[pause]

SJ: That looks like a well looked through log book.

AG: Just to prove Wing Commander Cheshire.

SJ: Yes that’s where he had gone to. That is local flying that was part of his training. [laugh]

AG: That’s right, I always say that he was my pupil.

SJ: [laugh] that’s brilliant. So what happened next, you were moved to 617 you were there for a six months.

AG: Yes and I done seventeen trips.

SJ: Seventeen trips.

AG: I got three more to do.[pause] ‘I will just have a cough sweet.’

SJ: That is no problem, that’s fine.

AG: [pause while uwrapping sweet] ‘Will you stay for some lunch?’

SJ: Oh, might do if that’s all right, yeah.

AG: I have got a beef casserole.

SJ: Lovely, that sounds fantastic.

AG: Right, I will heat it up in a minute.

SJ: [Laughs]

AG: ‘Sorry, I was, what was I saying —.

SJ: You were saying about 617 Squadron when you left.

AG: Yes I went to 9 Squadron who was the other squadron that had the tallboys, they didn’t have the grand slam, so that they still needed wireless operators. So I went over to 9 Squadron about three weeks before the end of the war. After we, I then had to make a decision, I was asked did I want to go to the far east against Japan. By that time I was married.

SJ: When did you get married?

AG: I got married the month before I joined 617, Iris never knew I had volunteered to go back.

SJ: Did you ever tell her.

AG: I have since, she was indignant. [laugh]. But I always said she was in a more dangerous situation as a nurse in Whipps Cross Hospital near the docks.

SJ: Was she always a nurse then?

AG: I didn’t say how I met her, did I?

SJ: You didn’t no.

AG: Can I digress?

SJ: Yes that will be fantastic to know.

AG: She was born in Woodford. But before the war they moved down to a little village called Rochford just outside Southend. And she wanted to be a nurse but they wouldn’t take her until she was seventeen. So she came to Echo as a copy typist. I was one of the senior, not senior clerks but I was, I was fairly well up. I had been there three years. And I met her and I liked the look of her and so after I went in the Air Force I kept in touch with her. And you know, I’d spent about no more than about ten days in her company, up to the time we got married. Because when I came on leave we always went to see a London show but that was about the only time we could get of. ’Forgive me sucking the sweet.’

SJ: Oh no it’s fine, not to worry.

AG: And that is how I met her. So I decided I didn’t want to go to the Far East I thought that having done about forty six trips, I didn’t , the neck had gone out too far. So I got posted to 50 Squadron at a place called Sturgate which was up near, in North Lincolnshire. And we were then flying; first of all we were flying prisoners of war from Brussels to England, in the Lancasters. We used to take, I think it was twenty or twenty four depending on what kit they got in the Lancaster fuselage sitting on the floor But they didn’t mind that as long as they were coming to England. After we got all the POWs back we then started bringing people back from leave from Italy. And we used to fly to Naples and pick up about twenty Air Force or Army people at a place call Pernicano, which is just outside Naples. Eh after a time they decided that was going to stop because shipping was available to bring them back in larger quantities anyway. And the Mediterranean was open so they stopped doing it. So I then got posted to do a code and cipher course down at a place called Compton Bassett near Calne in Wiltshire. And having passed that course I got posted to Germany ostensibly to be the CO of a small mobile signals unit. Which was one officer, one sergeant, one corporal and about ten men. When I got there I was told it was based at a place called Stade[?] between Cookshaven and Haverg. So I arrived at Stade[?] and the CO said. ‘Oh I am glad to see you’ he said. ‘I lost my adjutant about two weeks ago you are my new adjutant.’ I said. ‘No I have a mobile signals regiment.’ He said. ‘No I closed that down yesterday and you are my new adjutant.’ But I said. ‘I know something about flying but I know nothing about anything else.’ He said. ‘I’ll teach you.’[laugh] and he became a very good friend of mine. We did all sorts of things together, we got up very early in the morning sometimes at dawn and went and shoot deer. Quite unofficial we hadn’t got a license from the Military Government or anything and it ended up in a very humorous story. We had this, there weren’t very many of us, these base signals on your radar unit, refurbished these units to be sent round to the aerodromes and various places including Berlin. So there were only about fifteen of us I suppose. And we were having dinner or preparing to have dinner one night and we had got deer for dinner. This happened, Military Government people and ourselves we didn’t mingle sociably ‘cause there was nothing else. So they arrived about four o’clock and didn’t look like moving. So the CO said to me ‘What do we do?’ I said ‘Well as they are the guests of our mess this evening you had better invite them to dinner. And as they are our guests they won’t be able to do anything about it.’ So they sat down to dinner with us and ate deer. And they did let us know that they were aware of it. I think they had been told off, they had a [unclear] [laugh]. Well that, I ended up demobilised in August 1946 and I got reinstatement rights if I went back to Echo, but I was offered a short service commission of two years. But if I had taken that it would have meant in all probability the Air Force would have been reducing in size so much that I would have then been demobilised. And I wouldn’t have had reinstatement rights, having been in what was the regular Air Force for two years. So eh I went back to Echo. And so as I say I didn’t know anything about being an adjutant and certainly nothing about earning my living in civvy street. But I was fortunate, the man who interviewed me was the deputy chief accountant of EK Cole Ltd. And he knew because I had told him that I was keen on cricket because he was interviewing me in depth. He said ‘That’s a good thing I am a life member of Lancashire.’ So he took me on his staff and he taught me accountancy. I did take a correspondence course was meeker compared with what he told me. So I was never able to be a chartered accountant because I didn’t take articles. I was earning my living, by that time I was increasing my family.

SJ: How many children have you got?

AG: I’ve got three, two of them became nurses and one, the boy went into insurance.

SJ: You had two girls and a boy.

AG: I am proud of them all.

SJ: Oh yeah I don’t blame you.

AG: So I was in the deputy chief accountants department. Then he got promoted to be the chief accountant and then he became promoted to eh; financial secretary and accountant to a number of subsidiaries. So as he went up my situation went up with him.

SJ: You went up as well, did you enjoy that?

AG: I couldn’t have been an accountant in a professional office because that would have been dull. That would have been checking, checking, checking, checking. What I liked about being in industry, I was always in a place that was making things and you could go there and see it all happening. It was accountancy, it was very important accountancy, but eh —.

SJ: Very different from your RAF days though?

AG: Yes very much so. I was an active member of the 617 Squadron Association and we went to a number of reunions in Canada, Australia, New Zealand eh France as a unit, we’ve gone and made friends wherever we went. I haven’t been to the last couple number of places because Iris became, eh unreliable, she was unsteady. I couldn’t take her onto aircraft and coaches and things like that. She came to, she came to Australia and New Zealand and to Canada but the —, When we went to France and Germany and the Netherlands we went by coach and ferry, she hates flying.

SJ: [laughs]

AG: ‘Now where have I got to?’ Eventually we got taken over, first by Pye from Cambridge and then Phillips who are Dutch of course. But the British office was at Croydon and eh I became the financial accountant, financial director in a number of subsidiaries around the group. But I ended up, I always wanted to be somewhere near Southend because my parents were still alive. And I owed a lot to my parents, I didn’t want to move right out of their orbit. And I then went to Canvey Island to a components factory. First of all as the financial director and then as the managing director. And from there I went back to Southend as the eh; managing director of Echo Instruments which made instrumentation for industry. Then I retired.

SJ: How long have you been retired now?

AG: I retired when I was, I retired finally when I was sixty three. I first retired at sixty one when I left Canvey. And I only had been retired for about three months when my boss at Cambridge rang me up and said. ‘I am in trouble, can you help me?’ I said. ‘Well, help you in what sense?’ He said. ‘Can you come back and do a job looking after a subsidiary until I find a, a permanent managing director?’ So I did and I stayed two years.

SJ: [laugh] Why not?

AG: But it was a good period for me because I was drawing full pension and then I was drawing full salary so it made a nest egg for me when I did retire.

SJ: So it was worth it then?

AG: Yes; well I stayed in Shoeburyness just outside Southend until twelve years ago. But one of my daughters lived in West Row which is just to the West of Milden Hall and another one lived in Barton Mills.

SJ: I was going to ask why you moved up this way?

AG: Well my son was in Kent and the journey from Shoeburyness up to here was one hundred and ten miles. And when I got to eighty I decided that that was too far. So we moved up here to a place just the other side of Mildenhall, Brickcone Hall[?] and eh, it was too large but we loved it. And then Iris had trouble keeping her balance, damaged her hip. So I decided we had to be on the same floor so we moved here. Which was a retirement bungalow which suited us down to the ground.

SJ: And it is a lovely complex, it really is nice.

AG: It is, I sit here and we have mallard ducks and swans on the river and I watch them and they come and look at me and squawk.

SJ: [laugh] And you sit and look at them?

AG: I try, I do, if Iris was here with me I’d love it. But she is only two miles away.

SJ: That is not far. How long has she been in the care home?

AG: Since January, so eleven months. But she is happy there and she is safe. You see I had her home here at first after she came out of hospital eh, but I couldn’t look after her during the day and the night. And I was getting totally exhausted because every time she moved I woke up. So we decided that my savings would go to the wall and I would put her in the care home. And she is in a lovely little care home. She is well cared for and she is safe, so —.

SJ: Does she like it there?

AG: At first she missed us all because she saw the family every day. Well now I go in about five days out of the seven and the two girls go once. Because Rosalind is a practice nurse in Bury so ,

SJ: That is not far away?

AG: No. And she is married to a Canadian who eh and they go backwards and forwards. I think they have a permanent passage booked on aircraft [laugh]. And eh Jill has got four sons and five grandsons, my great grandsons, so we are largely together. And my son comes up —.

SJ: He is the link end.

AG: Yes. He comes up for a week about every six weeks, because he has retired now.

SJ: Has he got any family?

AG: No; he married a lady who was seven years older than him and it never happened, so —.

SJ: That is quite a big family you got then, grandkids and great grandkids.

AG: Yes, I am a very lucky man. Having survived the war I look round and think, ‘This family wouldn’t have survived if I had bought it.’

SJ: I know, yeah.

AG: Well they might have done, Iris might have married someone else, but.

SJ: It would have been different though.

AG: They wouldn’t have had my genes.

SJ: No exactly [laugh]

AG: I’ll heat the —.

SJ: I shall put this on pause shall I?

AG: Since I retired, lived in Shoeburyness, Mildenhall and here there has been a resurgent of interest in 617. And also strangely in Pye Cambridge. And I have been recruited, to say to do this kind of interview for Pye Cambridge. Because they are making a record of the activities of Pye in Cambridge, because it has been there ever since it was formed.

SJ: So they are getting a history together of that part of Pye?

AG: There is a historical museum which is bringing all these records together. So they are doing what you are doing and making recordings and eh —.

SJ: It is great it needs doing. I mean how do you feel about the project? How do you feel about the Bomber Command Archive project?

AG: Lets say this. After I have had a session like this or with John Nichol . Or with other things the squadron seems to send to me. Eh, like the Cambridge stamp centre and signing things happened. Undoubtedly I have a disturbed couple of nights. Because it has brought it all back. But then the family encourage me and I totally accept the fact, if people like me didn’t say what this was like. The written word is not necessarily understood. But I think if they hear peoples voice as you are doing now, it might stop wars happening. I thank my lucky stars, that my son didn’t ever have to go through the trauma of a six years war. It was, don’t get me wrong. I think it was necessary. Hitler wouldn’t have got stopped in any other way. And I think in a way Hitler getting stopped, Mussolini and Stalin also got stopped. Because the consequences of the nuclear bomb was so dreadful that it stopped. And I don’t think there would have been a nuclear bomb if it hadn’t have been for the war, ‘cause the money would not have been found.

SJ: Yeah.

AG: Do I sound too serious?

SJ: No. I completely agree with you. Lessons need to be learnt from the past, don’t they?

AG: I think those of us who went through it. Have kind of a duty to make sure these subsequent generations knew what it was like.

SJ: Do you feel this generation and future generations will understand how it was?

AG: It’s difficult to say. But John Nichol tells me his book had a huge print and he has sold a lot of copies. So that if it get put into houses and families and people must have been buying it to read at home. It didn’t all go to libraries.

SJ: No not at all.

AG: The younger people eh, might well have learnt from it. And the BBC have done a number of programmes about the Air Force and the war in general. The Navy, all those aspects have been fired[?] some of it must have sunk in.

SJ: Yes you would like to think so.

AG: Yeah. And I think we have a duty to make sure that it became available. But it is not something that I enjoy.

SJ: Yes I completely understand, yeah.

AG: Because, well my family were fortunate. My brother was in the Navy, he was on the Arctic Convoys on HMS London, and eh —.

SJ: What was your brothers’ name?

AG: Kenneth, Kenneth George. And he, he went in the Navy. Largely because of my father I think. My father was Thames Bargeman. There’s Thames barges on the wall.

SJ: Yeah, I noticed them when I came in, yeah.

AG: My father was a Freeman of the River Thames. And he was on Thames barges and then on Thames tugs.

SJ: Did your father have military background?

AG: No, in the First World War he was a barge captain. And he, he used to load ammunition at Woolwich Arsenal, and take it over to France to a place called St Valerie.

SJ: He had a very important job.

AG: He used to take it across the channel. Through all those minefields and what have you.

SJ: Very risky.

AG: Yes it was. And at the end of the war he was presented with the Maritime Medal.

SJ: Oh brilliant.

AG: But you know the chances that he took as a civilian. He should have got much more than that.

SJ: I know. What was you fathers name?

AG: George, George David. He lived until he was ninety four, the last six years with us at Shoebury.

SJ: You mentioned your brother. Did you have any more brothers or sisters?

AG: No just the brother. My mother had twins which were still born, my brother and I —. They really were, they were extremely poor in a sense. Because in the shipping slump of 1931, 32 the barges were laid up all over the East Coast. And he just got on care and maintenance pay which was hardly anything. And with that he was trying to run himself on the barge, tied up to a buoy and the family at home. So his savings gradually went. So he had to, he had a break down eventually about 1934. And he stayed on the water in a sense because he became the hand in an oyster dredger on the river Roch at Rochford. And he did that eh, about eight months in the year. Then he was unemployed for the rest of the year. So he dispersed his savings looking after his family really. So I did have a very big moral obligation to my parents who were the salt of the earth.

SJ: Yes they sound like they were, which was great. I think that generation they were, weren’t they?

AG: They were family minded.

SJ: They were mm.

AG: They, [pause] I don’t think they bought themselves a Christmas present. Where my brother and I always had one.

SJ: Yeah, what were your family Christmases like?

AG: The family, my father had one, two, three. Three daughters, three sisters and two brothers. And one of the aunts was a school teacher and she took a fatherly interest. So silly isn’t it, she was an aunt, she couldn’t take a fatherly interest [laugh]. An aunt interest in my brother and I. And he won an open scholarship, a total scholarship to Clarks College when he was thirteen.

SJ: Oh brilliant.

AG: It was the only one on offer in the whole of the area, and he won it. He went to Clarks College. By the time I got to and I was four years younger. By the time I got to the age when I was sitting exams. They couldn’t afford for me to be another drain on the family finances. So eh, I went to work at Ecko.

SJ: How old were you when you started there?

AG: I was fourteen.

SJ: Fourteen mmm. How did you feel about working, starting work so young?

AG: It was the common thing.

SJ: It was mmm.

AG: I was on the, I was at the village and I stayed at the village. I was only at the municipal college for a short time and I was working and doing it evenings. But the village, I was almost. Hardly any of us did further education but my family believed in it. So I did further education and my brother was good example to me that he had won an open scholarship.

SJ: That was brilliant.

AG: But the village had a tradition of going to work at fourteen.

SJ: Yeah. But they did didn’t they? I mean they is eighteen now when they leave school. It is a big difference these days.

AG: But I would say this about the great working school; it was first class. And they had dedicated people. We had two Welshmen who were school masters there and they gave up their Saturdays for sport. They never let us go to a fixture without one of them being there. You know it was —. After school they’d, we would go into the playground and get a matting wicket and play cricket. And they always did it in a —. I look at teachers these days and I think to myself. ‘You should have lived with those people, you would have learned an awful lot.’ They believed in the welfare of their students. Where as now they seem to want —. [Interruption]. ‘Come in.’ [shout]

SJ: Shall I put this on?

Collection

Citation

Sue Johnstone, “Interview with Syd Grimes,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 26, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/5519.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.