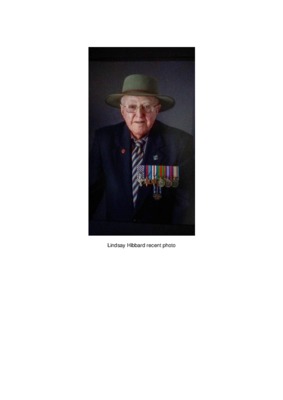

Interview with Lindsay Hibbard

Title

Description

Lindsay was born in Murwillumbah, Australia, before moving to Brisbane in 1927. He tells of growing up on the family, and how his eldest brother was killed in Malaya on the Thai Railway, and his older brother returning home to run the farm after his father passed away. Lindsay joined the Royal Air Force in 1942. He did his initial training at Kingaroy, before moving on to training as a wireless operator at Maryborough, completing that in July 1943. He tells of his experiences on the gunnery course at Evanshead, where his ‘claim to fame’ is that he got 30% of his hits off target. After going to San Francisco and New York, Lindsay tells of his trip across to Liverpool. Lindsay flew in Battles, and then went on Ansons, Wellingtons and Stirlings. He flew 32 operations, all with the same crew, including Nuremberg, Dusseldorf, the Dortmund-Ems Canal, to the oil refineries at various locations, and operations to bomb the U-Boat pens in Norway. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1945, after his aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire on the way to the target at the Politz oil refineries in February 1945. The anti-aircraft fire severed numerous cables, causing a failure of the intercommunication system, but Lindsay managed to make repairs. The pilot also received the same award for bringing the aircraft down safely. Lindsay jokes that his uniform was ruined as they could not get the oil out of it. After the war, Lindsay tells how he returned to the farm, his encounter with a lady who he used to date in Edinburgh, and his diagnosis of post-traumatic stress.

Creator

Date

Spatial Coverage

Language

Type

Format

Publisher

Rights

Identifier

Transcription

LH: Yes.

JM: So did that mean that you, your family was in Murwillumbah or, and they were staying there or –

LH: Yes, they were at that stage, they moved to Brisbane in 1927.

JM: Right.

LH: Yes, just for education, to be educated.

JM: Yep. And er, so 1927, so you had your first three years in Murwillumbah and then, and then Brisbane. What part of Brisbane were you in?

LH: Cooparoo.

JM: Cooparoo right. I’m not overly familiar with some of the suburbs of Brisbane, that one’s not ringing a bell. Which was that north, south, east?

LH: Oh it was towards the south, yeah.

JM: Towards the south, right.

LH: Near the Logan motorway.

JM: Oh, okay, right, right.

LH: Which wasn’t a motorway then.

JM: No, no, no, no, no, that’s right, yes, but I’ve, I’ve, I’ve driven up there and seen the turn off for the Logan motorway so that makes sense, yep, okay. So, from 1927 er, so that’s –

LH: 1939, we came back in 1939.

JM: Oh okay, to back to –

LH: To Tumbulgum.

JM: To?

LH: To the farm at Tumbulgum.

JM: Oh Tumbulgum, oh okay, so you had a farm there?

LH: My dad had a farm there from nineteen hundred and two.

JM: Right.

LH: He came up from Macklay in nineteen hundred and two.

JM: Mm mm.

LH: To the farm at Tumbulgum.

JM: Yep right, and so why, why were you –

LH: Still own it, well only some, the brothers still owns it, but anyway.

JM: Right, okay.

LH: Been in the family.

JM: All that since, that’s a hundred and sixteen years.

LH: Yes.

JM: My goodness gracious, and er, so did the whole family move to Brisbane?

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: So what, so what father, father just had somebody looking after the farm while you were up in –

LH: No he used to come down on Mondays –

JM: Right.

LH: To the farm and go back on Friday.

JM: Oh okay.

LH: Spend the weekend with him.

JM: Oh okay right, right.

LH: He had share farmers in.

JM: Share farmers in helping him, right.

LH: The farm was split into two farms.

JM: Right, right, okay, well that’s interesting. So you did your education in –

LH: That’s the reason mum nagged him into taking us to Brisbane so that we could go have a good education, completely wasted just quietly, but, [laughs], I’ve always been sorry that the poor old bugger [laughs], wasted all that money on us.

JM: Mmm.

LH: Went to the Brisbane Grammar School.

JM: Right, okay.

LH: Just on Brisbane [unclear]

JM: Yes, yes, a good school. And, and did you finish your Leaving Certificate there or -?

LH: No juniors, that was juniors.

JM: Intermediate.

LH: Came back when I was fifteen.

JM: Fifteen okay. Right, yes well if I did some arithmetic when you said you went back to ’39, fifteen, yes that’s right. 0kay so when you went back to the farm, did you then work on the farm?

LH: Yes.

JM: Right.

LH: I never learnt anything till I got on the job.

JM: [laughs] So basically you were just an offsider to dad on the farm.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: So what were you running on the farm?

LH: Well now there was dairies in those days.

JM: Yes, yes, very much so.

LH: We converted to cane after the war.

JM: After the war right, that was a fairly early conversion still though really, wasn’t it? You would have been one of the first cane –

LH: Well no, they used to have cane back, oh the sugar mill had been on the cleat since 1880 or something like that.

JM: Oh yes, with the Con, the Condong one you’re talking about?

LH: Yes, the Condong Mill yes, yes, and most of the farms grew some sugar but er, dad had a [unclear] went on the dairy, stayed on the dairy the whole time.

JM: Right and what and then he went back to the sugar afterwards?

LH: Well he died three months after I joined the Air Force.

JM: Oh I see.

LH: He died in 1942.

JM: Right.

LH: Yes, three months after I joined the Air Force. [phone ringing]

JM: Okay Lindsay’s now dealt with his phone call so that’s all good. So we were, you were saying your father died in ’42.

LH: Yes ’42 three months after I joined the Air Force, he had a heart attack, fifty five.

JM: Goodness me, okay so –

LH: I’d been away at that time initial training, ITS.

JM: Right, right okay, so that’s interesting.

LH: But er, they didn’t call me out of the Air Force because me brother was coming back from the Middle East, he’d been at the Battle of Alamein, and the night he was coming home .

JM: Right.

LH: But unbeknown to us somebody pulled strings in parliament and got him out so when he landed back in Australia to run the farm.

JM: Run the farm.

LH: ‘Cos mum didn’t have a clue.

JM: Yes, yes. So were there just you and your brother, one other brother?

LH: No just after that the eldest brother was killed in Malaya, on the Thai Railway, he was, well he died on that anyway. Then there’s my brother, the one coming back he was in the [unclear] and then there was me, there’s four years between each of us.

JM: Each of you okay. And so, so you, you were helping dad on the farm until you enlisted.

LH: Yes.

JM: And so you just enlisted when?

LH: I got in the Air Training Corps, I did a year in that before, well I started when it started up.

JM: When it started up.

LH: In Murwillumbah.

JM: In Murwillumbah, so that was what when you were sixteen/seventeen?

LH: Yeah, sixteen.

JM: Sixteen. And then you enlisted then as soon as you were eighteen.

LH: Yes.

JM: And you enlisted in Brisbane?

LH: Brisbane yes.

JM: Okay and then you did your initial training, you said, at Kingaroy.

LH: Kingaroy.

JM: So that would have been what early ’43, or did you start in late –

LH: Late ’42.

JM: Late ’42 so you would have started up there in December? Did you?

LH: No it was before that, sixth of the eleventh ’42.

JM: Yeah, that was your enlistment but what about your ITS?

LH: That’s when I went in.

JM: That’s when you went in, oh right, so that was Kingaroy. So after Kingaroy when did you do your WOP, your wireless operator?

LH: I did it at Maryborough.

JM: You did it as Maryborough and what date was that? That’s July ’43, you were certified on the fourteenth of the eighth ’43, so that’s July ’43.

LH: Yeah that’s was wireless.

JM: Yes that’s your wireless, that’s what I’m saying.

LH: Then we went to do the gunnery course.

JM: Yeah then you did the gunnery after that, yes, which I presume was at Evanshead?

LH: Evanshead, yes.

JM: So Maryborough was fourteenth eighth ’43 was the graduation of that, and then the gunnery at er, was graduation at Evanshead was 17th September ’43 so that’s all good, okay. So how did you find, what I mean, I guess we can backtrack just a second, the fact that you had joined the ATC you had, you had an interest in that?

LH: Yes, it was always going to be Air Force.

JM: It was always going to be Air Force, yeah, and as I say having joined the ATC then obviously the natural progression was to go to in –

LH: So as soon as you got your eighteenth birthday you didn’t do anything, they just sent us to the centre in Brisbane.

JM: In Brisbane.

LH: To be interviewed.

JM: Okay. And what, what, what process was there for putting you into wireless, did you ask to do wireless or did they say –

LH: When I enlisted I didn’t but then I, yes, I did.

JM: What, ask for wireless?

LH: Yes, when I first went up for an interview. Well I had a sister, see, who had all these pilots, and gunners, and navigators, [unclear] visiting her, wireless ops [unclear]. Well I always figured I wasn’t confident enough to put myself in the hands of a crew, you know, I never felt, I had to be part of the crew but not the pilot.

JM: Not the pilot, okay. So you specifically decided on, on wireless so that’s good, so then they were able to oblige and you um, did, did your wireless, and then of course the usual story that they got the wireless people to also do the air gunning course as well so you –

LH: I held a gunning gunnery hits on the [unclear] board for Evanshead.

JM: Oh did you.

LH: Yes, well he told me when I was, just when he left, before we left, they definitely give me a [unclear] and everything I had thirty percent hits on the grove which was unheard of.

JM: Oh really.

LH: Yes.

JM: Well there you go. Was that because you’d been doing some shooting on the farm?

LH: Well I fired little bursts, instead of long bursts, they had what they called a Vickers Go Gun, gas operated, and it used to jump around and we were in the back of Fairy Battles, and we had no communication with the pilot at all. To start firing he waved his wings and to stop firing he pumped the tail up and down. And we were attached to the floor by [laughs], by a, a, what we called a fair rein, it was clipped if you didn’t have that on, you bounced up and down, you really hit the top. [laughs]

JM: You made –

LH: And we used to shoot at aluminium patches on the water and sand patches on the gunnery range.

JM: Right, so the patches on the water were in the ocean I presume?

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: Out there off Lennox Head or something I suppose –

LH: No there’s a gunnery range, a bombing range just beside Evanshead.

JM: Right, right okay, interesting. And so you ended up with the top score, well at that point obviously.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: It would be interesting to know whether anyone ever bettered that after –

LH: Well I don’t think they would have.

JM: Yeah.

LH: Because you’re alone, the gauge wasn’t all that big [unclear]

JM: No.

LH: Used to jump around so much –

JM: Jump around so much.

LH: Yeah anyway.

JM: As I said –

LH: That’s said my claim to fame.

JM: Your claim to fame.

LH: [laughs]

JM: Oh I’m sure there’s a few other claims to fame, but um. as I say, did you do, when you were on the farm, did you do a lot of shooting –

LH: Oh we used to do a lot of shooting, oh yes.

JM: So therefore, you probably had quite a bit of, you were your aim was pretty, you know.

LH: Oh yes.

JM: And I guess, what were you shooting on the farm?

LH: Anything that moved, pigeons.

JM: Pigeons yeah.

LH: Pigeons.

JM: Did you have any foxes, rabbits or anything like that?

LH: No, there’d foxes but not rabbits.

JM: Did you shoot foxes as well?

LH: Well if we saw them we did.

JM: Yes, yes. So all of those moving targets would, would be very useful training for you in terms of –

LH: Yes, yes, oh I always thought I’d have been better as a gunner than a wireless op actually [unclear].

JM: Oh well, that’s all a good back story there so –

LH: It was no long, not long after this that we were sent to Sydney to get the boat, we didn’t know where we were going to.

JM: Going, no.

LH: Just put on the boat and sent to San Francisco.

JM: Yes okay. So you went down to um, you went to, you were sent to Sydney and then you –

LH: Transferred. We missed the first boat. What happened, they put us on leave when we left Maryborough, final leave they called it, and then we had to go to the South Brisbane Railway Station to get the train to Sydney, and the fellow, the fellow who was handling all these troops that were using the train, the train, he kept sending us home. And then they found that we should have been gone a month before, and anyway he put us on the train and sent us to Sydney and we missed the boat, and they sent us onto Melbourne and we missed the boat again, and then they sent us back to Sydney and then we got on the “USS Westpoint”, which was an American troop ship but it was an American top cruise liner before the war. “Miss America” it was before the war.

JM: Mmm.

LH: And believe it or not, we’d heard about these troop ship meals, you know, how terrible they were.

JM: Mmm.

LH: The first meal we had [unclear], turkey and asparagus and sweetcorn [laughs], we couldn’t believe it [laughs].

JM: So you lucked out, having had the inconvenience of going Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, all over the place, you ended up on –

LH: On the cruise ship.

JM: On the best ship.

LH: Three hundred and forty of us I think, on this forty thousand ton liner.

JM: Wow.

LH: Yes and we went to San Francisco.

JM: And you didn’t have any yanks, US troops of course, they –

LH: A few Americans, pregnant, no a few Australian pregnant women, and a few American wounded.

JM: Right.

LH: Yes.

JM: Right.

LH: But the women, there was a couple of dozen of them you know.

JM: Yes, yes.

LH: ‘Cos they were all coming this way.

JM: Yes, yes. So then, you had three hundred and fifty troops on this –

LH: Three hundred and forty, yes.

JM: Three hundred and forty troops on this huge boat, so you had a life of luxury compared to a lot of the other chaps.

LH: Oh hell yes, yes.

JM: Did you each have your own cabin or did you have to share?

LH: No, no, no, no, no, they put us in a very confined space.

JM: Oh did they now, oh.

LH: Yes, yes, a very confined space.

JM: Oh that wasn’t very nice.

LH: Well it was really, no, we had plenty of water, and plenty of everything you know.

JM: Yeah, yeah.

LH: Plenty of food, we could hardly get down the gangplank when we got to San Francisco [laughs]. And then they sent us across from San Francisco to New York, we got on the train.

JM: By train, yes.

LH: San Francisco and got off in New York, got off and then we were –

JM: No that’s right, and that was the normal thing, just to push you straight through. So then you got to New York, did you have any time in New York, before you left New York?

LH: Yeah we had a, had a I think a week or two, we were waiting, at that time that’s when the “Queen Mary” had to cruise in to, yeah, it had just got back into action. We didn’t go on the “Queen Mary”, we went on the “Andes”.

JM: Right.

LH: Just over twenty-seven thousand ton cruiser, we went from there to Liverpool.

JM: Right, oh Liverpool, okay, that’s different. So what date are we talking about here now? So, I guess if we finished the training, it has to be, you finished your gunnery training in September ’43, so this has to be end of ’43, potentially even early ’44?

LH: I think that the change of currency on the boat [pause], [looking through log book].

JM: Yeah, that’s right. Sorry.

LH: August 1943-44, air to sea.

JM: Yeah that’s you starting to do your gunnery stuff so we need to go past that.

LH: March/April ’44 that’s when we got in to Ansons.

JM: Ansons. Okay so obviously the point is that March, so obviously you’ve landed in the UK around about March, March ’44, is a good approximation for, for all we need at the moment. Okay so you –

LH: We were sent to advanced flying, thirty-first of the three, ‘43.

JM: Yes.

LH: That was Ansons.

JM: Yes, and what dates was that, that was the March and April was it?

LH: March/April ’44.

JM: Yes okay. And so what do you remember about that, that would have been the first time, because I mean –

LH: There was night flying.

JM: Night flying yes, ‘cos you had. wouldn’t have done, because your flying up until that date was only sort of sitting in the back of the other plane –

LH: Of the Fairy Battles.

JM: Fairy Battles, doing your –

LH: Being whacked [unclear].

JM: Yeah, yeah, so this is your first time in –

LH: Mainly Ansons.

JM: Er, a big plane, when you’re actually enclosed so to speak as well, because the Fairy Battles are open canopy there so, so was that the first time you’d been in a full plane like that.

LH: Yeah, yeah.

JM: Had you done any flying in the ATC, had you been up in the air at any time?

LH: No, no, no.

JM: So this was when you found out whether you really liked flying or not?

LH: Well I was always a bit worried about it [laughs] but it was better than marching [laughs].

JM: Yes.

LH: Well we got on the Ansons the thirty-first of the third ’43 to the thirteenth of the fourth ’44 [pause].

JM: Right, okay, and so –

LH: That was just for practice bombing mostly.

JM: Bombing, so basic flying, well advanced flying I should say, yes. So what did you do, so you probably did a, probably did at least one other, well you would have done OTU?

LH: We were sent to Silverstone on the fourth of the fifth ’44 to crew up.

JM: Oh okay, so that’s when you did your crewing up, yeah, okay. And what was, which squadron, what base were you at there?

LH: Silverstone.

JM: Silverstone, and did you have a squadron number there I should say?

LH: No, no, no, no.

JM: No, no, no.

LH: We just crewed up.

JM: Crewed up, yeah.

LH: They put, I think, thirty of each of you all –

JM: In a big room, square room.

LH: Didn’t know who they were, you had to sort yourself out.

JM: And so you, did you have any Australians, any of the chaps that you came over on the boat with, or any of the chaps that you done any of your training with?

LH: No, no, the fellows we came over on the boat with, they were there for wireless ops but none of the others.

JM: Yeah, so it was only the wireless ops that you knew.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: And obviously being only one on each plane, you weren’t going to end up together.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: So okay. So which, so what did you end up with in the crew?

LH: Well there was an Australian pilot and navigator.

JM: Right, who was your pilot?

LH: Jackson, Flight Sergeant Jackson.

JM: Yes.

LH: And er, and navigator Jim Wilson, and there was bomb aimer he, his name was Fred McClure, and then I was the other, I was the wireless op, and there were two pommie gunners.

JM: Right.

LH: Yes, so that was the six, you didn’t pick up the engineer until just –

JM: Oh once you start, almost dreaded, start ops.

LH: That was when you, oh yeah, when you got to heavy conversion.

JM: Heavy conversion, yeah that’s right, okay.

LH: So that went to [unclear] it’s on Wellingtons.

JM: Mmm, hmm.

LH: On the twenty-ninth of the fifth.

JM: Twenty-ninth of the fifth, okay, so all good.

LH: Then we were sent to 17 OTU at Towcester, at Towcester or whatever you call it. No that’s we’re still on Silverstone here. The fourth of the seventh ’44, yeah that was the last trip when we finished with Wellingtons.

JM: Right.

LH: Fourth of the seventh, yeah.

JM: Right, and then –

LH: And they wouldn’t even let us, they made us stay for the last one, but the pilot got married and they wouldn’t let us go to his wedding, yeah. We finished our last one with Wing Commander Lister, but anyway.

JM: Right, so then, so then you went into your OTU?

LH: No that was the end of the OTU.

JM: That was the end of the OTU, so when did the OTU end, that was at the fourth of the seventh was it?

LH: Ah, OTU.

JM: I wouldn’t have thought so, that I would have thought, it would have been a bit –

LH: Fourth of the seventh, yeah.

JM: Was that when it finished was it?

LH: Yeah, yeah, when OTU, that was on the Wellingtons.

JM: Right, okay. So what leave did you have in between any of this, so what did you do?

LH: Well we were given a week or two at the end of OTU and then we were sent to er, Heavy Conversion Unit [pause], Heavy Conversion Unit, Winthorpe, on the tenth of the eighth ’44, that was on Stirlings.

JM: Yep.

LH: Yeah, and that’s er –

JM: And that was probably about a month was it?

LH: [Looking through photos/book]

JM: Be careful, don’t rip them. It’s, it’s stuck there, so you probably won’t be able to separate that for the moment, but I will -

LH: Oh that’s it.

JM: Yeah but I wouldn’t, it’s very stuck up on this corner I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t be –

LH: The pages –

JM: Yeah, be careful, yeah well either that or it’s deliberately, looks like it’s been deliberately glued together so –

LH: Well there’s the summary for the course, that’s the Heavy Conversion, er, August/September 1944 unit [unclear] 1661, dated eleventh of the ninth ’44.

JM: Yes that’s right, that makes sense.

LH: I wonder why they glued them together?

JM: Oh possibly there was some figures that needed to be changed and rather than changing the figures they just glued the pages together to go into a new –

LH: Then there was the Lancaster Finishing School at Syerston, that was on the twenty-ninth of the ninth ’44, and the second of the tenth ’44. Then they sent us to Scotland.

JM: Yeah, okay.

LH: October ’44, 4th October.

JM: Right.

LH: Then we were given a few familiarise station exercises and then we were sent to Nuremburg.

JM: Right okay.

LH: Remembering what the one before [laughs].

JM: Yeah okay, well we’ll come to that in a moment, let’s just backtrack for a second. You said you had a week’s leave at the end of –

LH: At the end of OTU.

JM: OTU.

LH: Yes.

JM: And so what did you do, what sort of places did you go to?

LH: Oh well I always wanted to go to Scotland and we had a Scotch rear gunner, so I went up to Edinburgh with him, spent all my leaves in Edinburgh and then I –

JM: Right, right, well so that was good. And so you met his, did you stay with him and stay with his family?

LH: No, no, no, no, ‘cos he er, I had a hostel that started like the Australian Air Force started one later on, so we used to stay in hostel accommodation.

JM: Right, right, okay. And so did you see a bit of Scotland then did you, or just around Edinburgh?

LH: Mainly round Edinburgh but I got to know a few people there, lovely people, and up to Aberdeen and that’s about as far as we went.

JM: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well with only a week that didn’t give you much scope, but I mean –

LH: Well when we got on the squadron, you was supposed to get ten days leave every six weeks, but as the crews kept knocking off you kept moving forward, and then you had ten days every four weeks, and they were very good to us there was [unclear] give us five bob a day every day, every day, we were on leave that’s money, isn’t it.

JM: Oh my, yeah. So your crew altogether at this stage and at this point you’ve also now picked up your engineer I guess?

LH: Yes, we picked him up at the Stirlings, with the Stirlings.

JM: Yeah okay. And who was your engineer?

LH: A Joe Black, a Geordie from Newcastle.

JM: Right.

LH: Nice little fella.

JM: Yes, and so then um, you were posted to 57 Squadron and –

LH: 4th October ’44.

JM: 4th October, yep, and that’s, you did a few training runs?

LH: The first op was on the nineteenth, we did a fortnight’s familiarisation you know.

JM: Yeah okay. So your first op was –

LH: Nuremburg.

JM: Was Nuremburg. Nothing like a small task to start with?

LH: Yes.

JM: What was it –

LH: Well they lost ten per cent, they lost more on the trip before that than they lost in the whole of the Battle of Britain.

JM: Yes.

LH: Five Hundred and Sixty, they lost ten per cent of their planes on the trip before.

JM: Mmm.

LH: Over eighty planes. Eighty planes with [unclear] would you believe, yeah.

JM: So this would be in October ‘40?

LH: Yes, 19th of October ’44.

JM: Yep.

LH: And the second one was, the second was on the twenty-eighth that was to Bergen, Norway, U-Boats pens.

JM: Right. So what –

LH: That was a, oh no, the second op was the twenty-third, it was to Flushing in Holland, that was the second op.

JM: Right.

LH: That was done in [unclear], air gunners [unclear].

JM: Right.

LH: We nearly came to grief then because we got er, it was a beautiful day and the pilot didn’t put his retaining harness on, and we were just cruising along at about three and a half thousand feet, and then an anti-aircraft shell exploded in the bomb bay and put the plane in a mad dive. Up to three and a half thousand, and he didn’t have his harness on and he was floating in mid-air, and he ended up, he had to put his two feet on the control panels to pull us out. The only time I prayed [laughs]. Nearly wet, nearly wet me pants as well. I didn’t. We were all in mid-air, the plane was in a vertical dive –

JM: Vertical dive –

LH: Yes, yes, and we nearly came to grief then but anyway –

JM: So he managed, he just managed to exert enough pressure –

LH: Well he pulled us out yes, but well we didn’t have much clearance from the ground by the time he –

JM: Was it ground or water you were over at that point, ground?

LH: We were over the water going in to the downspin, but [unclear], well we’d have been over the sands, but that was where the gun emplacement was.

JM: Right.

LH: And the third one was er –

JM: Just a minute before you go to the third one, let’s go back to Nuremburg. What can you tell me about Nuremburg?

LH: That’s the third one. Oh no, it’s the first one.

JM: No, Nuremburg was the first one.

LH: Now when you go to, go to, before you go on ops your pilot is put in with another crew in –

JM: Second dickie?

LH: Yes, second dickie, and he did that, and when we got to Nuremburg nobody seemed to know what to look for. Well see, I’m inside the rear turret, and one of the gunners saw these lights out of the port and we went, and we were late over the target, nearly everybody had gone home then.

JM: Any particular reason for being late or-

LH: Well that’s because they’d missed, instead of turning off at the right time to make the bombing run, they’d overshot and had to turn round and come back.

JM: Back, oh.

LH: Yeah, yeah. And then once the bomb aimer got his sights on the thing, he told us, open the thing, put the nose down and go for it. Yeah, but we had quite a few near misses though shrapnel holes in the plane.

JM: Right, from that trip, from that?

LH: From anti-aircraft guns.

JM: Anti-aircraft guns.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: Well I mean I guess if you are on your own, you’re a bit more of a target when you’re sort of sitting out there on your own.

LH: Yes, yes, yes. And they’d all gone, yes. By then probably all the guns were in their fixed position, so they’d put them in a fixed position and just fire as many shells. As soon as they found what the bombing height was, they’d just fire guns into us, you know.

JM: Yes yes.

LH: But you couldn’t sort of aim at them. Anyway, that was another near miss.

JM: Yeah, yeah. So all those holes, golly gosh, yes.

LH: Then the third one was Bergen.

JM: Yes.

LH: That was over Norway a submarine pen.

JM: Gosh and what happened there?

LH: Nothing much happened –

JM: Nothing much –

LH: Oh well, it was a, it was one of those targets that they, the Germans put them near the village as a, and they generally tried to put up a smoke screen, but if you got in before it, and they hadn’t marked it, but they wanted you to sort of get near misses. And knock off population so we didn’t get too friendly, sort of thing.

JM: So did you have any pathfinders going in dropping anything for you or in advance, or were you on your own just doing your own thing?

LH: No, no, [unclear] there would have been a couple of hundred planes I suppose, yes building up.

JM: Right, gosh that’s a fair number.

LH: Yeah. As I say anyway, it was well marked, I mean.

JM: It was well marked by simply just the number of planes.

LH: Yes.

JM: Okay. So that’s the end, that’s getting towards the end of ’44?

LH: That’s the end of October, and then the 1st November was Homberg, that was oil refineries.

JM: Mmm.

LH: Nothing particular there I don’t suppose. And then that’s the 1st November, the 2nd November it was Dusseldorf, it was daytime yeah, that was the [unclear], then the 4th of November was Dortmund-Ems Canal. Strange to say that was one of the most dangerous targets in Europe because they relied a hell of a lot on the Dortmund-Ems for transport, and the only thing they’d do, we could do was, there were two viaducts in Gravenhorst and Ladbergen and let the water out, blow the [unclear]. Now the Germans, then they’d build them up again and just when they were about open, we’d go back and blow them down, so they’d know when we were coming and that’s why it was one of the most dangerous targets believe it or not.

JM: Because they organised their defences because they anticipated your return.

LH: Yes, yes. They nearly brought is down later on [unclear]. And then the next one from that was Turin, that was a tactical target, and that one the wheels, the undercarriage wouldn’t lock down or wouldn’t say that it was locked down, so we sent a crash [unclear] to Carnaby, but anyway it had just a malfunction in the electricals as it happened, so we landed on [unclear]. And then [unclear], oh that was at Carnaby. Then the next one was the twenty-first, that was Gravenhorst, had to go up and somehow bomb the other viaduct.

JM: Right, again was that a similar sort of story in terms of the way they protected the –

LH: Yes, yes, ‘cos they waited for us.

JM: Yes.

LH: And then the next one was Trondheim, Trondheim.

JM: Back up to Norway?

LH: Yes, back up to Norway, now that was sub pen again. Now what happened there we had to, had to fly at night under a hundred and fifty feet for a thousand miles and we didn’t have radio altimeters, and at one stage I dunno how the plane but what they call a long tailing area, a long –

JM: Yes.

LH: It’s got a lot of little ball bearings on the end of that –

JM: Ball bearings, yes.

LH: And that hit the water and tore up, it was only thirty feet under the plane.

JM: Under the plane.

LH: And everybodys screaming, “climb”, and [laughs] but er, to make it worse, we got there and then they put up a smokescreen and they couldn’t get a clear view to mark the target, so having done all that, we had to fly back with the bomb load.

JM: Without dropping the bombs?

LH: Yes.

JM: So did you drop them off –

LH: We didn’t have to fly back low, we came back at normal height.

JM: Normal height sort of thing, yeah. But did you drop the bombs?

LH: No, no, we landed with them.

JM: Landed with them.

LH: There’s only a few, well most of the ‘dromes were alerted all the way from top of Scotland down to Lincoln, expecting we wouldn’t make it to land there, but we got back to base. I think there was only two planes that were struggling a bit for base and you know. Well we landed with one hundred and forty gallons in the tank, but it was, it was, that was two thousand miles.

JM: Well I was going to say, it’s a long way up to Trondheim.

LH: Two thousand miles.

JM: Yep.

LH: Two thousand one hundred and forty-five gallons of petrol, so that worked out a mile to the gallon.

JM: Plus all the bombs.

LH: Carrying bombs and everything, and we carried them there and we carried them back, yes.

JM: Yes. Amazing, must have been a very good pilot to be able to manage the, the, to nurse it along to maximise, yes –

LH: Yes, yes. So that was –

JM: So that’s your pilot, and that was still, um, Jackson?

LH: Oh yeah, all the time they’re all Jackson.

JM: Yeah. What’s his first name?

LH: Jerry.

JM: Jerry.

LH: Jerald.

JM: Jerald, mmm mmm.

LH: Harcourt I think was his, J H, Harcourt, Jerald Harcourt Jackson.

JM: Oh, okay.

LH: And anyway that was the twenty, that was the 3rd November. Then we get to December [unclear], that was on the fourth. The sixth was Giesson, that’s night time raid. And the ninth was Heimbach Dam, the first drop on Heimbach Dam was abandoned, I don’t know why I record it anyway. And then we did a daylight on Heimbach later on, that was on the eleventh of December, then must have gone on leave.

JM: So you didn’t do, in December you didn’t do anything on the Baltic Fleet in um, um, I don’t know how you pronounce it. Gdynia or something like that [spells it out].

LH: Oh Gdynia

JM: Yes.

LH: No.

JM: No you didn’t do any of that, right.

LH: No. There’s just [unclear] and Heimback Dam, then we were put on leave.

JM: Right, so what did you do for your leave there?

LH: Edinburgh.

JM: Edinburgh again, yes.

LH: [laughs] yeah.

JM: Did you have some attraction up there by this stage or not?

LH: Well I did have some. Funny thing, in 1962 one of the girls I used to go out with turned up in the Tumbulgum pub as the barmaid.

JM: Good heavens.

LH: By then I had five kids and a wife and everything, and she thought we could just go [unclear] [laughs]. Anyway I never said anything to my wife ever about it, but anyway it was good [unclear] because the pub was full when she was the barmaid there, and the proprietor thought she was paying a bit too much attention to his, to her husband, so she fired her, and she took all the customers up to the Riverview Hotel at Murwillumbah [laughs]. You could have tried to get in, but bloody emptied the pub. Anyway how the hell she found me after twenty years after the bloody war well –

JM: Amazing, she must have been keen.

LH: Oh she was [unclear] she was beautiful.

JM: Well, well.

LH: Well now we come to January.

JM: Come to January.

LH: The 1st of January, back to Ladbergen again, the Dortmund Ems, and then on the fourth, Royan, that was a garrison of er, I don’t know, [unclear] the fifth that was [unclear], that was tanks [unclear]. Ah that’s one I’m think about. And then there’s the seventh was Munich, that was a long one.

JM: Anything stand out about that one?

LH: It was eleven and a half hours, the Klondean one, it was a very long flight. Sorry what did you say?

JM: Did that Munich, anything about the Munich trip stand out or just, or was it just –

LH: Only the Swiss, came back over Switzerland, you could nearly hear the people drinking gin slings, and all the lakes were black, all around was white, and all the lights were lit up, because all Europe was blacked out, oh beautiful, why we didn’t bail out I don’t know [laughs]. Oh beautiful. And then on the fourteenth, it was Merseburg [unclear] oil refineries. On the sixteenth was Brux, that was Czechoslovakia oil refineries, that was about ten hours that one, and Merseburg was ten hours too.

JM: Gosh.

LH: Yes, ten hour trip. That took us to the end of January, then put on leave again.

JM: Yep, Edinburgh again?

LH: Yep.

JM: Yeah.

LH: [laughs] That was done for January. Ladbergen again [unclear], and then on the seventh, Pölitz, that was oil refineries, and then, oh that’s one where we nearly came to grief at Pölitz. We got four direct flak hits that put the intercom out, and blew one tail off, it was a hell of a lot, hell of a thing to see, cracked through the main spar, er, not the main spar, the one that the landing flaps were on the –

JM: Yes.

LH: Cracked through that –

JM: Cross member –

LH: No, we didn’t have wings, these were on the landing flaps, and we didn’t know that and it could have come unstuck when we were landing, luckily it didn’t, I mean.

JM: Yeah till, unstuck. And this was in February would you say or late January?

LH: That was 7th February.

JM: 7th February, yep.

LH: And for some reason they gave me a gong for that, I don’t know what for, I didn’t know they posted it out to me [laughs]. Oh, asked if I wanted to go and get it in England [unclear].

JM: No.

LH: No well that was after Pölitz, it was oil refineries. And then the nineteenth was Poland, that was Leipzig, that was more oil refineries. Then the twenty-fourth it was a daylight back to Ladbergen, Dortmund Ems, that was the end of February.

JM: Mmm. There couldn’t have been too much left of it by that stage was there? Or what did they keep building rebuilding it back again, yes –

LH: No they kept building, you know, and I think they knew there’d be plenty of easy targets, you know, there was, they could concentrate on the night fighter force.

JM: Their artillery onto, yes. Bees to the honeypot again was their view, that they could whack ‘em all off, whack ‘em off.

LH: And then March, seventh of the third of March, Ladbergen again.

JM: Mmm.

LH: And then 5th March was Poland oil refineries. The 6th March was Szczecin, that’s the Baltic Port of Denmark , the Germans were evacuating faster than us, ahead of the Russians, well thought out, they, Szczecin was the Danish port, and er, when we went in to bomb they put, we didn’t know, they sent in mine layers just before we went in, and they mined the whole of the front of the harbour and as we started dropping bombs the ships all started up to get out of the harbour they ran into this minefield, yes. It was pretty, I felt sorry for the poor old people killed in that way, but you know [unclear]. And then the seventh, that was to Hamburg, that was oil refineries. And the twentieth was Poland again, Leipzig oil refineries, we was betting on them at that stage. And the twenty-third was Wesel, now we didn’t know that was the crossing of the Rhine, yes we did that.

JM: So you were part of that, that big mission there for that.

LH: Yes [unclear], troop concentration [unclear].

JM: So what did you have a specific target that you had to –

LH: No, no, I think they took Churchill along to view that and they pulled the troops back for miles from the target, It was a pretty significant move in the war.

JM: It was, it was, it was a turning point in terms of, yeah.

LH: Into Germany.

JM: Into Germany. that’s right, yeah, yeah. But you were just part of –

LH: Just part of the bombers.

JM: You don’t remember roughly how many, how many planes were up there that night? Was it, that was another night one I presume?

LH: Aye?

JM: Was that a night or a day?

LH: Oh yeah, night.

JM: Night.

LH: Yeah.

JM: You don’t remember how many were, planes were up that night?

LH: No, there would have been at least two-fifty but no, I don’t think it wouldn’t have been bigger than that I don’t think, but two-fifty was a fair, quite a lot of bombs to drop, ‘cos each one had about seven tons to drop so seven thousand, fourteen thousand pounds.

JM: That’s amazing the amount of bombs when you think two hundred and fifty planes all dropping that sort of thing.

LH: Then back to, back to March [unclear]. Now we can do April [unclear], Nordhausen, now we didn’t know that was a concentration camp at that stage. It was daylight, but when we were coming up on the target I can remember this, the Germans, if they knew what we were up to, they’d put up a box barage and that would be a wall of guns that would be pointed into a, into a put a box that the planes were going to fly through –

JM: Planes were going to fly through, yep –

LH: And then they’d fire as many shells as they could.

JM: Shells as they could.

LH: When we was coming up, it was a beautiful clear day, but this was like a thunder cloud, just when they opened the burst of shells, that’s how many were going, yes, yes, a bit scary but anyway. And then we come to Mölbis, Leipzig, power, oil refineries, and that was the end bit.

JM: So what’s that?

LH: 7th April I think.

JM: Yes, 7th April. But that in total were there –

LH: Thirty-two ops.

JM: Thirty-two ops yeah, that’s, and all the same crew right the way through?

LH: Yes, well the navigator missed one trip, he had the flu or something.

JM: The flu or something, yeah, yeah.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: But otherwise the complete –

LH: Otherwise it was the same crew

JM: The same crew, yeah, and therefore –

LH: So funny thing, when, when we got hit with lots of flak, you’ve got no idea the incredible amount of damage and yet nobody got hit, nobody no.

JM: That’s amazing isn’t it, that no one got hit, that was incredible.

LH: Yes.

JM: So then let’s go back to Pölitz, um, and you say that so, and that’s where you were, and after that, is where, a as a result of that you were given the DFC, awarded the DFC?

LH: Yes.

JM: Did all the members of the crew get the DFC?

LH: Only the pilot.

JM: The pilot and –

LH: Only me and the pilot.

JM: You and the pilot, right.

LH: It was Pölitz, wasn’t it?

JM: Pölitz, yeah.

LH: Oh yeah, Pölitz.

JM: So what with the, that’s where you had some of the biggest direct hits with the flak?

LH: Yes, yes, yes.

JM: Yes so –

LH: Well we had no idea of what, the plane flew, but why I don’t know. It was really, really, one tail was blown off completely.

JM: One tail gone, yes.

LH: It was such a mass of holes, yes.

JM: Did the, didn’t damage the hydraulics or anything so you had to –

LH: Oh yes I was covered in hydraulic oil, well it busted some pipes but er, and they couldn’t, couldn’t, the dry cleaners couldn’t get it out, had to, buggered me uniform, and I stunk like anything with hydraulic oil, yes. And we landed at, I can’t remember the, landed at down near the white cliffs of Dover, a base round there.

JM: Yes. So were you able to land properly?

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: You didn’t have to do a belly landing in the grass or anything?

LH: No, no, no, no. no.

JM: No.

LH: Well we were lucky, I think, I often wonder, this is just between you and me, how many losses were due to poor maintenance you know, because some planes they just went on and on and on and on and on. Like you all had your letters, and some letters kept going pretty, you know, pretty regularly you know, and I was often wondering whether maintenance had to do with some of it. It’s just my thoughts though.

JM: And did you, did you, after like that trip for instance did your plane, did you have to go onto a different plane then?

LH: Well no, we went back –

JM: They patched it up and –

LH: No we had to get back by train.

JM: Yeah, but the plane itself –

LH: Well they patched it up.

JM: Patched it up. So did you do any, so the next missions after that, ops did you do in a different plane or?

LH: No, it didn’t come back to the squadron until after we’d left.

JM: Right.

LH: And that was one of the things that stuck in me craw, because the crew that went down to fly it back to the base they, there was a, one of the WAAF’s at the station was getting an award to something and one of the London newspapers took the crew down to get pictures of her directing the plane in, and it was our plane, and they sent each of ‘em a big photo.

JM: A great big photo.

LH: He showed it to me but he wouldn’t give it to me, he didn’t. Miserable bugger.

JM: Who was that who showed it to you?

LH: It, it was a fella that did one op before the war ended and they’d gone down to pick it up.

JM: They’d gone down to pick it up. So they effectively were, nonetheless the paper didn’t have a clue the fact that this crew was purely doing a ferrying run and had nothing to do with the plane itself?

LH: Yes, yes, it was on a ferry run.

JM: Yes, yes, I see.

LH: So that’s it again, there’s the plane there you see [showing photo].

JM: Yep, yep, right.

LH: It had done ninety-seven trips by the end of the war.

JM: So you were, so you were flying “Sugar” were you?

LH: “Sugar”, yeah.

JM: Yeah, okay.

LH: And it had done ninety-seven trips by the end of the war and er –

JM: So what did you, so which one did you fly for the last, ‘cos you basically did another two months –

LH: Oh well I said, I think the last one was “W”.

JM: Yeah, you had basically two, two more months ahead of you, about another seven or eight.

LH: Yeah, they just put us on any plane that was available.

JM: Right, yeah.

LH: After, after Pölitz was “O”, “P”, “Q”, “W”, the last one was “W”.

JM: So would you say that there was any one event or sequence of events, out of all of that, that stayed with you more than anything else?

LH: No not really, just that we were incredibly lucky in stages.

JM: Lucky, yeah.

LH: No I think luck played a hell of a part really, but we had a good crew you know, a very good navigator and a very good pilot and yes. He used to worry me, he was so small but [laughs], and the funny thing, he couldn’t even drive a bloody car and two years later he’s flying a plane [laughs].

JM: It’s a common story that many of them were flying planes before they had licences, that’s what is a very common story and it’s just so, so bizarre that, and not only were they flying planes but they were flying planes in the most extraordinary difficult and dangerous circumstances and, and it just –

LH: Eighteen hundred killed training you know.

JM: That’s right extraordinary numbers. And then, with, so then you were, was on leave before you then discharged –

LH: We was put on leave until we were –

JM: Until you discharged, so that was April, so you basically had nearly six months, April, May, June, July, August, September, five months, so you had some leave over in the UK, and then you were, when did you come back to Australia?

LH: Well, I had my twenty-first birthday on the boat we came back through the Suez via Panama Canal.

JM: Right, well just a second the leave that you had after you concluded, you completed your tour –

LH: We went on leave until we were called to Brighton.

JM: Right.

LH: And then that was about a month, and from there we waited for a boat to come home, and that was “The Andes”.

JM: Again. So you went over and back on the same –

LH: Yes, we went over we crossed the Atlantic on “The Andes”, and we came all the way back to Australia on “The Andes” through the Panama Canal. It was a very interesting trip.

JM: Oh.

LH: And then when we got back here we were put on leave and then of course, the war ended before even we were given any jobs, and then I must have been a nutcase because while I was on leave, I got a telegram asking if I’d take a job, if I was interested in distant um, taking charge of a section of thirty-four WAAFs, mind you, in Bradfield Park and discharged, and I knocked it back [laughs]. And then later, there was one time, asked me if I’d like to go back to the victory ceremony on “The Sydney” to England, and I knocked that back. I must have been a bloody nutcase.

JM: Mmm.

LH: But anyway that’s that. I just wanted to get out.

JM: Yeah, you wanted to get out and er, um –

LH: Two offers like that, bloody hell.

JM: Good offers. So you don’t recall any particular reasoning, apart from the fact that you’d just had enough and you wanted out? Is that probably the, just the main -

LH: Well the war was over really –

JM: Yes that’s right, the war was over by that stage. So just backtracking there for a second, when you were on leave before you went down to Brighton, was that back to Scotland again?

LH: Yes, Aberdeen and that yeah, yeah. Oh we got in with some returning PoW’s, sort of thing, they’d been in German PoW camps, wild as ever, yeah, yeah [laughs].

JM: Yeah –

LH: Everybody’s letting their hair down sort of thing, yes.

JM: Well that’s right, I mean, imagine what it would have been like for those guys in the PoW camps.

LH: Oh, boys open like jack rabbits, hey no, to tell you what they must have been well looked after ‘cause they were all in pretty good condition.

JM: Okay. So then you had your twenty-first birthday on the boat on the return home?

LH: Yes.

JM: And um, and you said you came home, you, and you, the route for your return home?

LH: Through the Panama.

JM: The Panama, so that was an interesting experience.

LH: Yes, yes. They wouldn’t let us off the boat at Colón, that was the Atlantic side of Panama because the mob before us went through the town and wrecked it –

JM: Wrecked it, yeah.

LH: Yes, so they wouldn’t let us off, we had to stay on the boat.

JM: Right.

LH: [unclear].

JM: And were you confined to a small area again?

LH: On the boat?

JM: On the boat

LH: Well we –

JM: Were you allowed a bit more, spread out a bit more?

LH: Well you had your bunk, you had your bunk, but you had the run of the boat sort of thing.

JM: So how, but I suppose you would have been –

LH: But I couldn’t get over, we, we was warrant officers of course, not officers, and we were warrant officers and because oh, up to sergeant they were treated like the troops, but we had stewards and everything and you had everything set out on tables, table cloths and everything, yeah. Oh, we lived like bloody princes all the way home.

JM: All the way home, yeah.

LH: Yeah.

JM: And were there a few more troops on board, coming home, than there were going out?

LH: I think about two thousand, I think about twenty-two hundred I think on the boat coming home.

JM: Yeah, yeah. So slightly more than going over.

LH: Yeah, there were a couple of hundred FANYS, that’s Field Ambulance National Service Women, and that was it I think. And the officers looked after them, they didn’t let the troops [laughs].

JM: Didn’t let the troops near them, protected them, yeah.

LH: Yeah [laughs]. I tell you what, if you came through it you wouldn’t miss it for quids, you know you don’t think of the odds, it but it’s a really, a really good experience anyhow.

JM: How do you feel it changed your life?

LH: Well I was told, 1945 to 1984 that I had post-traumatic stress for all that time. Well I didn’t say anything, I knew I wasn’t right, but at one stage I used to ball, start crying for no bloody reason. I, I, you know, I’m still a bit of a nutcase, but thirty nearly forty years after the war [unclear], he said, ‘you should have been on a pension at the end of the war’, but nobody read it.

JM: Nobody recognised it.

LH: They had, if you got that in Bomber Command you’re classified LMF, yeah and that went on your record, yeah. Sorry if I was a bit rude but anyway, yeah. And then in the First World War, they used to shoot them for cowardice, yeah. I can’t, I know some fellas used to disappear off the squadron but we never sort of queried it so maybe they could have been some breaking down.

JM: Mmm, right.

LH: But I always used to look out the window when we took off, think, now there’s twenty going and nineteen coming back, surely the odds were in my favour, but, well you sort of think like that, but I don’t know why, yeah. Probably funny, you probably think it’s funny.

JM: No I don’t think it’s funny, I mean it’s, it’s just an amazing um set of circumstances to be working through when, when you know you are not even twenty-one. I mean it’s just, I think of what, what you chaps went through and what youth of today sort of sees as a problem for them and I think they, they don’t, their not in the same ballpark, it’s just a terribly different world so.

LH: I think the secret was not to let it get to you.

JM: Yeah.

LH: Not, not to dwell on things that you did do. But the thing that stuck in me crew and I didn’t get a campaign medal, that really stuck in me crew.

JM: Which campaign medal was that?

LH: For Bomber Command, you didn’t get a campaign medal. You could send away for one in 1970, but it wasn’t a, a one that was recommended by the Air Force.

JM: But there is one that’s now available for the Australian Bomber Command.

LH: Yes I got one.

JM: Oh you did get one.

LH: I sent away for one.

JM: Right, yeah.

LH: It was in 1972 –

JM: No, no, no, no. This is within the last few years.

LH: No, no that was just a –

JM: A clasp.

LH: A clasp, yes.

JM: Yes, yes.

LH: I stuck it on and it fell off and I don’t know where the hell it is anyway, yes.

JM: Right.

LH: And they told us that, and when I rang up, that’s another thing that stuck in me craw, I rang up about that to somebody over in England and they said, ‘Oh you contact somebody down in [unclear] because you’re colonials’. I thought, mmm, right buggers –

JM: No there –

LH: They, they sort of looked on us as a different class but they didn’t then.

JM: No, no, that’s right.

LH: But I thought it was a bit of an insult actually.

JM: So which particular, so which you’ve got 39.5 Star.

LH: Yes.

JM: Yeah, what else and which and –

LH: Oh I’ve got them all on a, on a thing there.

JM: Okay well we’ll get back, we’ll get those shortly then, we’ll come back to those. So then you came back, so there were quite a few Australians in the crew there, there was what, there was only one, one Englishman wasn’t there, two?

LH: Two, two.

JM: One was Scottish.

LH: Three, the engineer and two gunners.

JM: The engineer and two gunners that’s right. So did you keep in touch with the pilot, the navigator, or the bomb aimer, once you all came back?

LH: No I never, I never was one for writing letters, some of them contacted me. The bomb aimer ended up a homeless alcoholic and he died at er, fairly well he was not an old man, but anyway, and he was really young so I don’t know why, whether, why it would have been him but, his father was a top Melbourne surgeon.

JM: Goodness.

LH: And, and he well, I don’t know.

JM: What about Jerry and um –

LH: No, Jerry who was a lawyer and, and he ended up at Tukka, down on the Murray, and he married a, a fine lady and she came out here.

JM: Do you know if he’s still alive or you don’t?

LH: No, no I’m the only one left out of the crew.

JM: You’re only the one left, yeah, right.

LH: I was the baby of the crew, yes.

JM: Crew right.

LH: The mid upper gunner was twenty-eight, and the rear gunner was thirty-six, but no pretty older than me.

JM: Goodness, thirty-six is very old, yeah.

LH: Yeah, yeah.

JM: I mean, twenty-eight was considered old but thirty-six was even older, but yeah, and compared to you being less than twenty-one –

LH: Yeah, well, Jim, Jim Wilson was about three years older. That’s a funny thing now, he got engaged after the war to a pommy woman, and when he came back here, his mother was in a nursing home with a full time nurse, and he ended up marrying the nurse and cancelling the other one. Now the other one married an American Mustang pilot and she went back to California.

JM: America.

LH: Now here’s where the funny thing happened, Jim’s wife died in 1980 something, late eighties, and he was moping around and his crew, oh no, his kids bought him a trip on a Russian cruise liner, this is incredible, on a Russian cruise liner.

JM: Yeah, to?

LH: Wheeled him onto the liner and said, “Stay there, don’t come back.”

JM: Right, where was this Russian cruise liner going?

LH: I don’t know but anyway the, on the cruise liner the American, the pommy dame that he was engaged to and got married, her husband had died and she was on the Russian cruise liner.

JM: Yes.

LH: Now you wouldn’t read about it.

JM: You would not read about this.

LH: You would not read about it. So anyway, the outcome was that he used to go over and stay with her for four months, and she came out here and stayed at his place for four months, and then they had four months apart. But you, you couldn’t think that up if you were writing a book could you, you could not think that up.

JM: Unbelievable. And what that’s the way they –

LH: Well she yes, she died a few years ago and he died.

JM: They continued that way until they both, until she passed away basically.

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: What an incredible story, I really am –

LH: But you’d have thought she would have had a shitty on him for dumping her in the first place.

JM: Yeah, that’s right, yes.

LH: But that’s, that’s war.

JM: Mmm, that’s right indeed. So then once you discharged in September, you’re back in Australia in September ’45?

LH: Yes.

JM: And knocked back the other bits and pieces, so what, you come back up here to –

LH: No it never shifted from me, it’s the best place in Australia you know.

JM: I know that. So you’re back up here to the farm and –

LH: Yeah well, sort of at a loose end, didn’t know, I didn’t make, I made a bad mistake in I could say bought this war service scheme here, where you bought the farm and then they funded it at three per cent.

JM: Yep.

LH: But I didn’t take that up because my dad was taken, and we end up splitting the farm up, the three boys that was, took a third each, and we arranged, see, dad had left everything for life interest to me mum and we ended up buying it off her at a price that we paid so much a year that if she lived to be ninety-five that she’d have a good income for the rest of her life.

JM: For the rest of her life.

LH: So that’s how we got control of the farm, sort of thing.

JM: Right, yeah.

LH: And then we converted to sugar.

JM: And then you converted to sugar, yeah. And so did all three of you convert to sugar or -

LH: Yeah, well I was the first one but the others followed on.

JM: Oh okay. And so, so then you each had your own part of the old farm?

LH: Yes, yes.

JM: So who ended up with the house?

LH: There were three cottages on the farm.

JM: Right.

LH: But when I got married I, I built another house.

JM: Right, yeah.

LH: And luckily I got the third of the farm with that house on it.

JM: Right.

LH: With the house and the cottage. Oh, me youngest brother got the, the bigger house, because it was thirty-six squared, that’s pretty big.

JM: And when did you get married?

LH: 1952.

JM: Was it a local girl I take it?

LH: Yes, well the family didn’t sort of approve, we were known as the wild Hibbard’s [laughs], but I started to pick her up once [laughs] one, to take her out one night [laughs], as I walked up the side of her house, I heard her father say, ‘Here comes the yokel’ [laughs]. Anyway, she must have known I had nothing because I had the arse out of me pants and she worked in the bank so it must have, so it wasn’t money she married me for [laughs]. Blimey, they were the days.

JM: But you made a go of it and you –

LH: But that’s what I say, these fellas who were supposed to have married bliss, I don’t know. This fella reckoned I, I should have been, should have been treated for it right back then, but I, I had to pay, you had to earn a living then, and I think that, you know, one thing that worried me in Vietnam they gave them a listen now. When you go for your interview, these are the questions that are being asked and here’s the answers you’re given, that’s why I’ve got a mate getting nine hundred bucks a week and he’s no thicker than you or me. So there’s a lot of fellas playing the system, I mean, not right, but anyway.

JM: So you married in ’52 and then you had at least one son?

LH: Yeah, I had five kids.

JM: Five kids.

LH: A son, three daughters, and a son.

JM: Right. So did they stay on the farm or did they go off and do other things?

LH: No, they all, oh one want to stay on the farm but for a reason, oddly I had to, well I figured that the way sugar was going that it was going to be in trouble, so I sold out.

JM: Right.

LH: While there was a quid in it.

JM: Yeah.

LH: Mmm. I helped in Meadow Farm and I was a partner in it and that, and when I did that he, he sold his too.

JM: Mmm.

LH: But the only, he only went in it [unclear] two hundred thousand, hundred and fifty thousand, he ended up getting eight or nine hundred thousand for it when he sold it.

JM: That’s all right.

LH: He and his wife, he started playing silly buggers and they split up. But he’s got a good job now in tourism, always been able to walk out of one job into another and another sort of thing.

JM: Into another.

LH: And there always good jobs.

JM: That’s good. And where, when you got out of the farm, where did you go then, what did you do?

LH: Oh no I didn’t retire from the farm until I was seventy-six.

JM: Yes, yes.

LH: Yes, then I came straight here.

JM: Oh, okay, right, that’s when you sold out.

LH: Yeah, yeah. But by then I had twelve flats in Murwillumbah, and I kept the farmhouse, which was a mistake as it turned out, but anyway, I left that to the daughter. When I sold out, it was worth about seven hundred and fifty thousand but when [unclear] took off and all the people moved up to Murwillumbah, the traffic passed the door, reaped it’s value.

JM: Yes, yes.

LH: Could have used it, I went on the stock market and did all right.

JM: Mmm, well that’s quite, quite a –

LH: I don’t know if it helps you.

JM: Well the point is Lindsay, when we discussed, when we were setting all this up, is that, you know there’s just not recognition given to the Bomber Command people in the past and this is just a very belated way of making sure that some of recollections, true recollections of those veterans is recorded for posterity and that’s what it’s all about.

LH: Oh yes.

JM: That’s why –

LH: I really think they could have given ‘em more recognition with a campaign, a proper campaign medal [telephone ringing]. It was for putting solar panels on the roof and I tell you what, you send away to one, one charity –

JM: And you have a hundred back.

LH: Hah [unclear].

JM: Yeah that’s right.

LHL: Anyway.

JM: No, well I think we are probably just about wrapping up, we’ve probably covered most of the things that we needed to cover, the, yeah, I don’t, your crew obviously were a tight group –

LH: They weren’t one’s for partying but some crews had a lot of time in the pub and this that and the other, but they weren’t like that, no, no.

JM: And none of them, they were all good solid citizens.

LH: Solid citizens, yes.

JM: And none of them had any real superstitions or carried good luck charms or anything like that?

LH: Not that I know of no, no.

JM: But even if they did it was obviously worthwhile because of the fact that you all got back safely right through.

LH: Very steady, very steady lot, yes. I always had it stuck in my mind, it was something me dad told me from the First World War, ‘don’t ever volunteer for anything, don’t ever’. So when we were picking a crew, I didn’t go looking for a crew, I just stood back and let everybody sort themselves out, and the last crew looking for what got me [laughs], which wasn’t a very good bargain but that was my outlook on.

JM: Yes, well that’s right, clearly you, it worked, because, I mean, you clearly had a good pilot because he managed to get you home safely after all those ops after some pretty hairy experiences, so that’s even more important so yeah.

LH: Had a good navigator, that was very important.

JM: Indeed, indeed. So at this point, we’ll wrap up the formal part of it and as I say again, thank you very much for your time, it’s been marvellous talking to you.

LH: I don’t know why they waited until most of them are dead because –

JM: Unfortunately, but I mean it’s better than nothing.

LH: [laughs] Not much.

JM: Thanks Lindsay.

JM: Yeah, we’re just talking to Lindsay Hibbard again on 23rd February, continuing on from our interview on 21st February 2017, we are just talking in a bit more detail about a couple of the ops he did. 16th January, that’s in ’44, yeah. January ’44?

LH: October ’44.

JM: No I want the 16th January ‘44

LH: ‘45

JM: ’45, sorry my apologies, yes ’45, January ’45. Okay, 16th January ’45.

LH: Sixteenth, Lancaster –

JM: Ops, Bruge –

LH: Czechoslovakia ops –

JM: [unclear] yes.

LH: Oil refineries.

JM: Yes.

LH: Twelve five hundred standards and one four thirty standards.

JM: And you were on three engines?

LH: Bombed on three engines.

JM: So what was the story there, were you, how did you lose the, the other engine?

LH: It was a runaway, what you call a runaway prop, it just sort of disengages from the motor and got up to I think, to six thousand revs and if they hadn’t of controlled it and brought it back it would have caused a fire, but it was a malfunction of the propeller so they shut that motor down.

JM: Shut that motor down and then just continued on and completed?

LH: We bombed on three engines.

JM: Yeah.

LH: We jettisoned six five hundred pound bombs to, when we lost the prop so that at twelve thousand feet, yeah.

JM: Right okay.

LH: And he got a DFC for that.

JM: Sorry?

LH: He got a DFC –

JM: The pilot?

LH: The pilot.

JM: Yeah okay, the pilot got a DFC for that, yes that’s understandable, to manage all of that, and to have complete, to have successfully complete the bombing raid as well and then get back home again, that’s pretty good to say the least. So that time you were DXT so –

LH: Yes.

JM: Yes okay. So all right, and then on the 7th February ’45, you were on –

LH: Lancaster ops for Pölitz.

JM: Pölitz, yes. Four direct flak hits here.

LH: Yes, yes. Is that the one that we crashed on?

JM: No, not that one.

LH: Well we were [unclear].

JM: So what sort of damage was that, how much damage?

LH: Oh god, it blew the tail off and there was bloody hundreds and hundreds of holes, you know, the H2SN was blown off, it made a bit of a mess of the plane but nobody got hit.

JM: Nobody got hit. And what, did you have any extra –

LH: Oh yeah we rolled –

JM: Roles to do?

LH: Knocked the intercom out, and I don’t know, I didn’t know what I was doing but I fixed it anyway, ‘cos that’s what they gave me the DFC for, it went out twice.

JM: Mmm, right. What did you have to do to fix it?

LH: I had to find, find a set of wires in amongst the bloody carnage and mess and connect them up again.

JM: And at this stage there’s still flak coming around hitting left, right and centre was there so that you were –

LH: From the first here, yeah, and then there was some later on, it had it on the –

JM: Citation?

LH: Citation.

JM: Let’s pause a minute while you perhaps get the citation out. Right, Lindsay’s just got the citation here for me and it reads, ‘Warrant Officer Hibbard has throughout a large number of operational sorties proved to be a wireless operator of great skill and ability. On one occasion in February 1945, his aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire shortly before reaching the target area, this resulted in the severing of a number of cables causing the failure of the intercommunication system. Warrant Officer Hibbard quickly traced the seat of the damage and effected repairs. Whilst over the target, the aircraft was again hit by anti-aircraft fire and the intercommunication system rendered unserviceable, but with cool confidence, this warrant officer once more effected repairs. Warrant Officer Hibbard has, at all times, displayed outstanding courage, determination and initiative’.

LH: Yeah.

JM: Terrific.

LH: I didn’t think I was that good.

JM: Well I think there’s a fair degree of modesty here Lindsay, which comes back to, I suspect, to some of your country upbringing –

LH: I think they built it up a bit I didn’t think it was that good.

JM: Well the fact that you got it all working again and you had to do it not once but twice, it just means that the amount of flak you guys were copping and, as you say, got so much blown off.

LH: We landed at Manston –

JM: Manston, yeah. And did the pilot get a bar or anything as well?

LH: Not a bar, he just got a DFC.

JM: Yes, but I thought you said he had already been given the DFC for in the January.

LH: No, no, no, oh no, he didn’t get a bar for that.

JM: No, oh okay. And did any of the, none of the other crew members got any recognition out of that flight?

LH: No, no.

JM: Because you were having to try and do things in amongst a whole pile of ricocheting and everything else. Yes, okay. So that was probably, I think that was the last, that was the second, so that was the last time you flew DXU.

LH: Yes but that was the squadron commander’s plane actually I think.

JM: Right.

LH: It wasn’t –

JM: Right, oh okay. So he obviously must have been either in a different plane or not on that raid?

LH: No, he wasn’t on that raid.

JM: Oh okay, okay well that’s, that’s basically the couple of things that I had picked up on just going back through my notes and that’s, that’s good. And then is there anything else that you had thought of that we didn’t cover when we chatting a couple of days ago.

LH: No, haven’t.

JM: So you were flying in a few different planes over the course of your tour, with as you say a fair proportion was in “Sugar” but you certainly had a few more –

LH: Oh yes, because they had to maintain them.

JM: Planes, yes, that’s right, so that you were rotated round a little bit while they maintained it, and that, that new one, the one you were on over at Pölitz, that would have needed a fair bit of maintenance to get, before that could go back up in the air again?

LH: It was Pölitz that Teddy got shot down wasn’t it?

JM: No I –

LH: MacDonald, Teddy MacDonald.

JM: Yeah, yeah, but it was –

LH: It was either Pölitz or Rositz -

JM: I think it might have been Rositz, but because that was in January so –

LH: No February was Rositz.

JM: Yes, but he was.

LH: I said it was either Pölitz or Rositz that it was.

JM: Well he, I haven’t got my notes in front of me and I just, but I know it was January that he went down. And he was headed towards Leipzig from memory, I think Leipzig sticks in my brain as to where he was headed towards but he didn’t actually get there.

LH: Must have been the oil refineries that time. Oh well anyway.

JM: Yeah, so that’s it, yes, thank you very much, thank you again, and I shall stop the recording now.

Collection

Citation

Item Relations

This item has no relations.