Fate Deals a Blow

Title

Fate Deals a Blow

Description

Extract from "But Not in Anger". Story of a Hastings of 53 Squadron on route from El Adam to Castel Benito Tripoli which shed a propeller blade which struck the fuselage injuring the co-pilot and cutting the tail control rods. Relates story of crew flying the aircraft using passengers moving up and down fuselage to raise and lower the nose. The aircraft landed short of runway at Benghazi and the crew were killed in crushed cockpit but most of the passengers survived. George Medal and King's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air were awarded as result to an officer who tended the wounded co-pilot and the rest of the crew.

Top left - remainder of the extract.

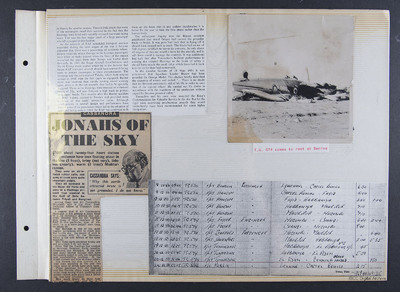

Top right - photograph of the crashed Hastings upside down at Benina.

Bottom left - newspaper cutting - Jonahs of the sky. Story of a Hasting that crashed in the Gulf of Sirte leaving passengers and crew in life rafts. Comments on poor reputation of Hastings aircraft for crashes.

Bottom right - extract from Ned Sparkes's log book from 8 December 1950 to 24 December 1950 listing 13 sorties.

Top left - remainder of the extract.

Top right - photograph of the crashed Hastings upside down at Benina.

Bottom left - newspaper cutting - Jonahs of the sky. Story of a Hasting that crashed in the Gulf of Sirte leaving passengers and crew in life rafts. Comments on poor reputation of Hastings aircraft for crashes.

Bottom right - extract from Ned Sparkes's log book from 8 December 1950 to 24 December 1950 listing 13 sorties.

Language

Format

One printed document, one newspaper cutting, one log book extract and one b/w photograph mounted on two album pages

Is Part Of

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

PSparkesW17010028, PSparkesW17010029

Transcription

[underlined] Extract from 'BUT NOT IN ANGER' [/underlined]

Fate Deals a Blow 18

Shortly before 2000 hours on 20 December, 1950, Hastings TG574 of No 53 Squadron, Transport Command, prepared to take-off from El Adem, near Tobruk. The captain was Flight Lieutenant Graham Tunnadine and co-pilot, Flight Lieutenant S.L. Bennett. There were four other crew members and 27 passengers.

TG574 was returning from Singapore nearing the end of an experimental slip crew schedule. Since 1945 Transport Command's Far East route had been operated in rather leisurely fashion, the same crew flying the aircraft throughout and night-stopping at selected points. As postwar commitments increased, the Command felt obliged to abandon this uneconomic use of aircraft and revert to the wartime slip crew system, whereby the aircraft flew day and night, making only the essential refuelling and servicing halts, with fresh crews taking over at appropriate staging posts.

Early in December four crews were accordingly pre-positioned along the route, and TG574 was flown to Singapore trying out the new, fast schedule. She was now homeward bound, carrying the four experienced Hastings crews who had completed their legs of the flight – plus Squadron Leader Thomas Colin Lyall Brown, a Transport Command medical officer who was studying any aircrew fatigue problems emerging from the new timetable. Three other passengers had joined at Karachi.

After staging through Colombo, Karachi, Habbaniya and Fayid, the Hastings had made an unscheduled stop at El Adem to top up with fuel before pressing on to Castel Benito, Tripoli. At 1958 she was airborne and the passengers were mentally blessing the operations staff for having planned to complete their experiment in comfortable time before Christmas. The aircraft plodded up to 8,500ft, and they listened with experienced ears to the changing engine note as she settled down to the 185-knot cruising speed. All was well. Fully conditioned to the monotonous roar of four Hercules engines, some promptly fell asleep, a few played cards or read, while one or two watched the black and silver desert sliding past, lit by the three-quarter moon.

On the flight deck, Tunnadine, aged 28, with some 2,300 flying hours in his log book, told Bennett to get his head down for a while in the rest compartment rigged up just forward of the passenger cabin, as it would be his task fly the aircraft on from Castel Benito after refuelling. His place up front was taken by Squadron Leader William G. James, another qualified Hastings pilot.

162

There was a fleeting hint of trouble 42 minutes after take-off. One of the back-seat drivers thought he noticed a vibration, possibly caused by an engine becoming unsynchronised. Moments later, while he was considering whether to pass some gently chiding note up to the flight deck, there came a sharp bang from the front of the aircraft. This was followed by a violent juddering which suggested something badly amiss. Awakened instantly, the passengers remained seated, confident that whatever the problem, the pilots would ask if they wanted any assistance. After another minute or two, which dragged by like hours, the air quartermaster appeared and requested Squadron Leader Brown to go forward, then asked one of the most experienced pilots to talk to the captain on the intercom.

On the flight deck nobody yet knew exactly what had happened. Tunnadine reported that he had lost all power from the port inner engine (No 2), and had no elevator or rudder control. Only the ailerons were working. With nothing but lateral control, the aircraft was descending and there seemed to be little he could do about it.

Meanwhile, Brown, having negotiated a sizeable gash in the floor, found Bennett still on the rest bunk, pinned to the floor beneath a pile of wreckage, barely conscious, with his right arm severed and other grievous injuries.

It did not take the crew long to establish the cause of their perilous situation. What had happened was that the propeller of No 2 engine had shed one of its blades. In flying off it had scythed through the fuselage – where part of it was still embedded in the opposite wall – cut the tail control rods as well as critically injuring Bennett. The three remaining blades, out of equilibrium, had wrenched the engine – plus part of the wing leading edge and the port undercarriage – free from its mounting to fall away to the desert a mile and a half below. The disturbed airflow over the great gash in the wing was seriously aggravating the handling difficulties.

A rapid check by Flight Sergeant Idwal Johns, the engineer, showed that there was no hope of locating and repairing the severed tail control rods. RAF Benina, near Benghazi, had acknowledged 574's May Day call, and was only 19 minutes normal flying time away, but at the present rate of descent the aircraft would hit the ground long before that. After further discussions over the intercom it was decided that the only possible way of maintaining fore and aft control was quickly adjusting the position of the load. First the baggage and small freight items were shifted

[page break]

to the rear, but this made insufficient difference, so while one of them remained in contact with the captain, the passengers themselves moved aft. Gradually the nose began to rise, though there were several over-corrections and some hasty to-ing and fro-ing before Tunnadine was able to acquire reasonably positive control of the flight attitude by adjusting the position of one or two passengers. Having established the Hastings in level flight, he was then able to begin a gradual descent, headed towards Benina, which in normal circumstances would have been overflown. Next he tried gentle turns to port and starboard, using the throttles to boost or reduce engine power as necessary to swing the aircraft in the required direction. At the first attempt the nose went up and the aircraft began to shudder, indicating that a stall was imminent, but an urgent order to move some passengers forward brought the nose down again just in time.

Rarely can any transport pilot have faced such an appalling dilemma. The easiest of the decisions – whether to make a belly landing – had already been made for him since half the undercarriage lay on the desert surface some miles behind. The only way of achieving a reasonable crash landing would be to lose height as gradually as possible, then try to raise the aircraft's nose with a burst of engines just before she touched the ground. But he had only three engines and was already fighting the asymmetric effect caused by the unbalanced power on each wing. And how long those three engines would continue to operate was debatable; they had already exceeded maximum temperature in fighting the drag caused by the damaged wing.

As the Hastings neared Benghazi the beach to the north-east, with its mile upon mile of sand gleaming whitely in the moonlight, looked particularly inviting – but Benina's station commander advised against its use because of obstructions. Tunnadine was now able to talk on his VHF radio direct to the control tower at Benina, and he told them that he had decided to use their runway. A flarepath was laid out, the military hospital at Benghazi alerted and an army fire tender despatched to help on the airfield.

TG574 arrived overhead near Benina with about 6,000ft still in hand. The flickering flames of the gooseneck flares marking the runway, and the lights of Benghazi offered some comfort, though the most difficult part was still to come. Tunnadine made several wide circuits of the airfield, gingerly descending to 1,000ft, with the passengers still acting as a human counterweight to trim the aircraft. The six escape hatches were removed, but the large parachute doors were left in position lest any sudden inrush of air should affect the flying characteristics in any way.

Brown, still tending the terribly injured co-pilot, was no novice in flying matters, having made 80 jumps while on the staff of the Parachute Training School. He fully understood the perils of the landing which lay ahead, and knew that those in the front would be poorly placed if the Hastings crashed. Nevertheless he insisted that his duty was to remain with his patient. He had injected morphia and treated the injuries as best he could, and was lying down with Bennett in his arms, providing warmth from his own body and holding together the worst wounds with his hands.

At 2149 hours the medical officers and ambulances from Benghazi reached Benina. The flarepath was complete and the crash crews, ambulances and fire tenders positioned at a point on the perimeter track near the downwind end of the runway. Benina control informed Tunnadine:

'We are all ready for you to come in to land'.

'Going out to sea to make final approach', replied Tunnadine.

'Good luck. Hope you make it'.

'I'll need a bit of luck'.

It was now 69 minutes since Hastings TG574 had been damaged. As Tunnadine brought the aircraft down from 1,000ft by throttling back his engines he began to turn through 180 degrees to line up on the flarepath. The lights of Benghazi were on his port wing-tip. His airspeed indicator showed 140 knots, the lowest speed at which he could maintain any control. Ten miles away the flares showed up against the blackness of the desert. He dare not risk using the flaps, which might produce a nose-down attitude which he would not be able to correct.

For the passengers, knowing only too well the critical nature of the next few minutes, the ordeal was one of agonising suspense. 'Any one of us would cheerfully have jumped out on the end of an umbrella had one been available' said one of them afterwards. They waited in silence, each man alone with his private thoughts. Some were still standing, ready to move as required for instant trim changes and the nightmare atmosphere was heightened by the intermittent bellowing of the engines, since violent throttle movement was necessary to adjust the aircraft's attitude during final stages of the descent. When the aircraft was within feet of the ground, the passengers still standing slid rapidly into adjacent seats and strapped themselves in. Tunnadine was desperately trying to keep the Hastings level. The ground came nearer.

'I can't see the end of the runway'.

These were his last words to the control tower. After their exhibition of such superb airmanship, it was tragic that luck should desert the crew in the final seconds.

The aircraft struck the ground about a quarter of a mile short of the runway. In front of a gently sloping hillock which had obscured the lights. The initial impact was very gentle, though inevitably the propellers ploughed into the ground and the engine nacelles began to break up. Had it not been for the slope all would have been well. This caused the Hastings to become airborne again for about 100 yards, then the starboard wing hit the ground and broke off. The aircraft rolled on to its back, slewed round in the reverse direction and slid along the rough ground for 360 yards before coming to a halt. The time was 2155.

Crash crews were on the scene within 90 seconds, though fortunately there was no fire. To their surprise they found that most of the passengers had scrambled out, having suffered little more than relatively minor cuts and abrasions. Those still inside the fuselage, dazed and shaken, were quickly helped out. The wreckage of the hideously crumpled nose section held little promise of any survivors, and the four crew members on the flight deck were killed. Despite Brown's valiant efforts, Bennett also died before he could be rushed to hospital.

Apart from its unusual features this accident has a place

163

[page break]

in history for another reason. There is little doubt that most of the passengers owed their survival to the fact that the Hastings were fitted with suitably stressed rearward facing seats. This was the first major crash of a large passenger aircraft equipped in this fashion.

As the network of RAF scheduled transport services expanded during the later stages of the war it became apparent that there was a percentage of accidents where, despite relatively minor damage to the fuselage, passengers were killed or badly injured when the force of the impact wrenched the seats from their fittings and hurled them forwards. In 1945 the Royal Aircraft Establishment and No 46 Group made studies which led to the decision that future RAF transport aircraft should have rearward facing seats to protect passengers in these circumstances. The Hastings and the twin engined Valetta, which both entered service in 1948 were the first types so equipped. Rather more was involved than simply turning round existing seats, since to do the job properly they had to be specially designed. Those in the Hastings were stressed to withstand forces of 20g, and also featured a high back to protect passengers' heads. Two months after the Benina accident an RAF Valetta crashed in Sweden and provided more evidence of the seats' protective value. Although developments in aircraft design and performance have altered some of the parameters which led to the adoption of rearward facing seats in 1948, the RAF has continued to fit them on the basis that in any sudden deceleration it is better for the seat to take the first stress rather than the human body.

The subsequent inquiry into the Benina accident established that metal fatique had caused the propellor blade to break. It was pure bad luck that in flying off it should have caused such a crash. The blade had an arc of 360 degrees in which to leaves [sic] its consorts. In only about 40 degrees of this arc would it have hit the aircraft, and in still fewer could it damage the controls. It was additional bad luck that after Tunnadine's brilliant performance in coaxing the crippled Hastings to the brink of safety it should have struck the small ridge which launched it back into the air for that fatal somersault.

In the [italics] London Gazette [/italics] of 18 May 1951 it was announced that Squadron Leader Brown had been awarded the George Medal. The citation briefly described the sequence of events and ended: '... There is no doubt that he (Brown) consciously risked his life in order to save that of the injured officer. He carried out his duties in accordance with the traditions of his profession without regard for his own personal safety.'

Tunnadine and his crew were awarded the King's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air. But for the rigid rules restricting posthumous awards they would undoubtedly have been recommended for some higher recognition.

[page break]

[photograph]

T. G. 574 comes to rest at Benina

[page break]

CASSANDRA

JONAHS OF THE SKY

FOR about twenty-four hours sixteen gentlemen have been floating about in the blue (I hope), briny (not very) tideless (nearly), warm (I trust) Mediterranean.

They were on air-inflated rubber rafts, and some of them were quite important people.

They all belonged to the Royal Air Force and were in a Hastings aircraft that crashed in the Gulf of Sirte between Tripoli and Benghazi.

Among them was Air Commodore Morshead, who is the Chief Staff Technical Officer of Transport Command.

I suggest that if Air Commodore Morshead is not getting a little tired of being personally ditched and narrowly escaping with his life, together with those of other members of the RAF in this particular type of aircraft, he is a more patient man than he might be.

The Hastings is one of the most hapless aeroplane ever to climb into the hostile sky. Its record of peril is approached only by the Hermes – which is the civil version of the same machine.

Why these earth-attracted brutes are not grounded, I do not know.

Since 1949 the Hastings has crashed at Salisbury, Benghazi, Sicily, Ismailia,Greenland and Abingdon. It has also had many narrow squeaks that have fortunately ended in safe but breathless and blood-chilling landings. It has killed thirteen and injured many others.

The Hermes has been involved in at least nine accidents in the past two years, some of which have been fatal.

These machines, both the Hastings and the Hermes, share many odd and lethal vices among which shedding propellers – which most pilots find a handicap – has been noticeable.

How much longer do these four-[text missing]

[boxed with picture] CASSANDRA SAYS:

[italics] "Why this earth-attracted brute is not grounded, I do not know." [/boxed]

[page break]

[columns] a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h. [/columns]

[a] 8.12.50 [b] 09.05 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Lyneham – Castel Benito [g] 6.50

[a] 9.12.50 [b] 04.00 [c] TG530 [d] F/Lt Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Castel Benito – Fayid [g] 5.00

[a] 9.12.50 [b] 11.55 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Fayid – Habbaniya [g] 2.50 [h] 1.00

[a] 10.12.50 [b] 04.15 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya - Mauripur [g] 7.10

[a] 11.12.50 [b] 01.55 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Mauripor – Megombo [g] 7.10

[a] 15.12.50 [b] 04.50 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Foster [e] Engineer [f] Megombo – Changi [g] 6.20 [h] 2.00

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 02.40 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Foster [e] Engineer [f] Changi – Megombo [g] 8.00

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 13.10 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Stafford [e] Passenger [f] Mecombo - Mauripor [h] 6.40

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 22.35 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Davenport [e] Passenger [f] Mauripor – Habbaniya [g] 2.00 [h] 5.35

[a] 19.12.50 [b] 12.15 [c] TG574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya – El Adem No 2 Eng U/S. [g] .45

[a] 20.12.50 [b] 08.45 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya - El Adem [g] 5.50

[a] 20.12.50 [b] 18.00 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] El Adem – Bennina CRASH LANDED [h] 1.50

[a] 24.12.50 [b] 08.15 [c] TG [deleted] 514 [/deleted][inserted] 526 [/inserted] [d] F/O Perrin [e] Passenger [f] Bennina - Castel Benito [g] 215

TOTAL TIME ... [g] 967.40 [h]348.35

Fate Deals a Blow 18

Shortly before 2000 hours on 20 December, 1950, Hastings TG574 of No 53 Squadron, Transport Command, prepared to take-off from El Adem, near Tobruk. The captain was Flight Lieutenant Graham Tunnadine and co-pilot, Flight Lieutenant S.L. Bennett. There were four other crew members and 27 passengers.

TG574 was returning from Singapore nearing the end of an experimental slip crew schedule. Since 1945 Transport Command's Far East route had been operated in rather leisurely fashion, the same crew flying the aircraft throughout and night-stopping at selected points. As postwar commitments increased, the Command felt obliged to abandon this uneconomic use of aircraft and revert to the wartime slip crew system, whereby the aircraft flew day and night, making only the essential refuelling and servicing halts, with fresh crews taking over at appropriate staging posts.

Early in December four crews were accordingly pre-positioned along the route, and TG574 was flown to Singapore trying out the new, fast schedule. She was now homeward bound, carrying the four experienced Hastings crews who had completed their legs of the flight – plus Squadron Leader Thomas Colin Lyall Brown, a Transport Command medical officer who was studying any aircrew fatigue problems emerging from the new timetable. Three other passengers had joined at Karachi.

After staging through Colombo, Karachi, Habbaniya and Fayid, the Hastings had made an unscheduled stop at El Adem to top up with fuel before pressing on to Castel Benito, Tripoli. At 1958 she was airborne and the passengers were mentally blessing the operations staff for having planned to complete their experiment in comfortable time before Christmas. The aircraft plodded up to 8,500ft, and they listened with experienced ears to the changing engine note as she settled down to the 185-knot cruising speed. All was well. Fully conditioned to the monotonous roar of four Hercules engines, some promptly fell asleep, a few played cards or read, while one or two watched the black and silver desert sliding past, lit by the three-quarter moon.

On the flight deck, Tunnadine, aged 28, with some 2,300 flying hours in his log book, told Bennett to get his head down for a while in the rest compartment rigged up just forward of the passenger cabin, as it would be his task fly the aircraft on from Castel Benito after refuelling. His place up front was taken by Squadron Leader William G. James, another qualified Hastings pilot.

162

There was a fleeting hint of trouble 42 minutes after take-off. One of the back-seat drivers thought he noticed a vibration, possibly caused by an engine becoming unsynchronised. Moments later, while he was considering whether to pass some gently chiding note up to the flight deck, there came a sharp bang from the front of the aircraft. This was followed by a violent juddering which suggested something badly amiss. Awakened instantly, the passengers remained seated, confident that whatever the problem, the pilots would ask if they wanted any assistance. After another minute or two, which dragged by like hours, the air quartermaster appeared and requested Squadron Leader Brown to go forward, then asked one of the most experienced pilots to talk to the captain on the intercom.

On the flight deck nobody yet knew exactly what had happened. Tunnadine reported that he had lost all power from the port inner engine (No 2), and had no elevator or rudder control. Only the ailerons were working. With nothing but lateral control, the aircraft was descending and there seemed to be little he could do about it.

Meanwhile, Brown, having negotiated a sizeable gash in the floor, found Bennett still on the rest bunk, pinned to the floor beneath a pile of wreckage, barely conscious, with his right arm severed and other grievous injuries.

It did not take the crew long to establish the cause of their perilous situation. What had happened was that the propeller of No 2 engine had shed one of its blades. In flying off it had scythed through the fuselage – where part of it was still embedded in the opposite wall – cut the tail control rods as well as critically injuring Bennett. The three remaining blades, out of equilibrium, had wrenched the engine – plus part of the wing leading edge and the port undercarriage – free from its mounting to fall away to the desert a mile and a half below. The disturbed airflow over the great gash in the wing was seriously aggravating the handling difficulties.

A rapid check by Flight Sergeant Idwal Johns, the engineer, showed that there was no hope of locating and repairing the severed tail control rods. RAF Benina, near Benghazi, had acknowledged 574's May Day call, and was only 19 minutes normal flying time away, but at the present rate of descent the aircraft would hit the ground long before that. After further discussions over the intercom it was decided that the only possible way of maintaining fore and aft control was quickly adjusting the position of the load. First the baggage and small freight items were shifted

[page break]

to the rear, but this made insufficient difference, so while one of them remained in contact with the captain, the passengers themselves moved aft. Gradually the nose began to rise, though there were several over-corrections and some hasty to-ing and fro-ing before Tunnadine was able to acquire reasonably positive control of the flight attitude by adjusting the position of one or two passengers. Having established the Hastings in level flight, he was then able to begin a gradual descent, headed towards Benina, which in normal circumstances would have been overflown. Next he tried gentle turns to port and starboard, using the throttles to boost or reduce engine power as necessary to swing the aircraft in the required direction. At the first attempt the nose went up and the aircraft began to shudder, indicating that a stall was imminent, but an urgent order to move some passengers forward brought the nose down again just in time.

Rarely can any transport pilot have faced such an appalling dilemma. The easiest of the decisions – whether to make a belly landing – had already been made for him since half the undercarriage lay on the desert surface some miles behind. The only way of achieving a reasonable crash landing would be to lose height as gradually as possible, then try to raise the aircraft's nose with a burst of engines just before she touched the ground. But he had only three engines and was already fighting the asymmetric effect caused by the unbalanced power on each wing. And how long those three engines would continue to operate was debatable; they had already exceeded maximum temperature in fighting the drag caused by the damaged wing.

As the Hastings neared Benghazi the beach to the north-east, with its mile upon mile of sand gleaming whitely in the moonlight, looked particularly inviting – but Benina's station commander advised against its use because of obstructions. Tunnadine was now able to talk on his VHF radio direct to the control tower at Benina, and he told them that he had decided to use their runway. A flarepath was laid out, the military hospital at Benghazi alerted and an army fire tender despatched to help on the airfield.

TG574 arrived overhead near Benina with about 6,000ft still in hand. The flickering flames of the gooseneck flares marking the runway, and the lights of Benghazi offered some comfort, though the most difficult part was still to come. Tunnadine made several wide circuits of the airfield, gingerly descending to 1,000ft, with the passengers still acting as a human counterweight to trim the aircraft. The six escape hatches were removed, but the large parachute doors were left in position lest any sudden inrush of air should affect the flying characteristics in any way.

Brown, still tending the terribly injured co-pilot, was no novice in flying matters, having made 80 jumps while on the staff of the Parachute Training School. He fully understood the perils of the landing which lay ahead, and knew that those in the front would be poorly placed if the Hastings crashed. Nevertheless he insisted that his duty was to remain with his patient. He had injected morphia and treated the injuries as best he could, and was lying down with Bennett in his arms, providing warmth from his own body and holding together the worst wounds with his hands.

At 2149 hours the medical officers and ambulances from Benghazi reached Benina. The flarepath was complete and the crash crews, ambulances and fire tenders positioned at a point on the perimeter track near the downwind end of the runway. Benina control informed Tunnadine:

'We are all ready for you to come in to land'.

'Going out to sea to make final approach', replied Tunnadine.

'Good luck. Hope you make it'.

'I'll need a bit of luck'.

It was now 69 minutes since Hastings TG574 had been damaged. As Tunnadine brought the aircraft down from 1,000ft by throttling back his engines he began to turn through 180 degrees to line up on the flarepath. The lights of Benghazi were on his port wing-tip. His airspeed indicator showed 140 knots, the lowest speed at which he could maintain any control. Ten miles away the flares showed up against the blackness of the desert. He dare not risk using the flaps, which might produce a nose-down attitude which he would not be able to correct.

For the passengers, knowing only too well the critical nature of the next few minutes, the ordeal was one of agonising suspense. 'Any one of us would cheerfully have jumped out on the end of an umbrella had one been available' said one of them afterwards. They waited in silence, each man alone with his private thoughts. Some were still standing, ready to move as required for instant trim changes and the nightmare atmosphere was heightened by the intermittent bellowing of the engines, since violent throttle movement was necessary to adjust the aircraft's attitude during final stages of the descent. When the aircraft was within feet of the ground, the passengers still standing slid rapidly into adjacent seats and strapped themselves in. Tunnadine was desperately trying to keep the Hastings level. The ground came nearer.

'I can't see the end of the runway'.

These were his last words to the control tower. After their exhibition of such superb airmanship, it was tragic that luck should desert the crew in the final seconds.

The aircraft struck the ground about a quarter of a mile short of the runway. In front of a gently sloping hillock which had obscured the lights. The initial impact was very gentle, though inevitably the propellers ploughed into the ground and the engine nacelles began to break up. Had it not been for the slope all would have been well. This caused the Hastings to become airborne again for about 100 yards, then the starboard wing hit the ground and broke off. The aircraft rolled on to its back, slewed round in the reverse direction and slid along the rough ground for 360 yards before coming to a halt. The time was 2155.

Crash crews were on the scene within 90 seconds, though fortunately there was no fire. To their surprise they found that most of the passengers had scrambled out, having suffered little more than relatively minor cuts and abrasions. Those still inside the fuselage, dazed and shaken, were quickly helped out. The wreckage of the hideously crumpled nose section held little promise of any survivors, and the four crew members on the flight deck were killed. Despite Brown's valiant efforts, Bennett also died before he could be rushed to hospital.

Apart from its unusual features this accident has a place

163

[page break]

in history for another reason. There is little doubt that most of the passengers owed their survival to the fact that the Hastings were fitted with suitably stressed rearward facing seats. This was the first major crash of a large passenger aircraft equipped in this fashion.

As the network of RAF scheduled transport services expanded during the later stages of the war it became apparent that there was a percentage of accidents where, despite relatively minor damage to the fuselage, passengers were killed or badly injured when the force of the impact wrenched the seats from their fittings and hurled them forwards. In 1945 the Royal Aircraft Establishment and No 46 Group made studies which led to the decision that future RAF transport aircraft should have rearward facing seats to protect passengers in these circumstances. The Hastings and the twin engined Valetta, which both entered service in 1948 were the first types so equipped. Rather more was involved than simply turning round existing seats, since to do the job properly they had to be specially designed. Those in the Hastings were stressed to withstand forces of 20g, and also featured a high back to protect passengers' heads. Two months after the Benina accident an RAF Valetta crashed in Sweden and provided more evidence of the seats' protective value. Although developments in aircraft design and performance have altered some of the parameters which led to the adoption of rearward facing seats in 1948, the RAF has continued to fit them on the basis that in any sudden deceleration it is better for the seat to take the first stress rather than the human body.

The subsequent inquiry into the Benina accident established that metal fatique had caused the propellor blade to break. It was pure bad luck that in flying off it should have caused such a crash. The blade had an arc of 360 degrees in which to leaves [sic] its consorts. In only about 40 degrees of this arc would it have hit the aircraft, and in still fewer could it damage the controls. It was additional bad luck that after Tunnadine's brilliant performance in coaxing the crippled Hastings to the brink of safety it should have struck the small ridge which launched it back into the air for that fatal somersault.

In the [italics] London Gazette [/italics] of 18 May 1951 it was announced that Squadron Leader Brown had been awarded the George Medal. The citation briefly described the sequence of events and ended: '... There is no doubt that he (Brown) consciously risked his life in order to save that of the injured officer. He carried out his duties in accordance with the traditions of his profession without regard for his own personal safety.'

Tunnadine and his crew were awarded the King's Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air. But for the rigid rules restricting posthumous awards they would undoubtedly have been recommended for some higher recognition.

[page break]

[photograph]

T. G. 574 comes to rest at Benina

[page break]

CASSANDRA

JONAHS OF THE SKY

FOR about twenty-four hours sixteen gentlemen have been floating about in the blue (I hope), briny (not very) tideless (nearly), warm (I trust) Mediterranean.

They were on air-inflated rubber rafts, and some of them were quite important people.

They all belonged to the Royal Air Force and were in a Hastings aircraft that crashed in the Gulf of Sirte between Tripoli and Benghazi.

Among them was Air Commodore Morshead, who is the Chief Staff Technical Officer of Transport Command.

I suggest that if Air Commodore Morshead is not getting a little tired of being personally ditched and narrowly escaping with his life, together with those of other members of the RAF in this particular type of aircraft, he is a more patient man than he might be.

The Hastings is one of the most hapless aeroplane ever to climb into the hostile sky. Its record of peril is approached only by the Hermes – which is the civil version of the same machine.

Why these earth-attracted brutes are not grounded, I do not know.

Since 1949 the Hastings has crashed at Salisbury, Benghazi, Sicily, Ismailia,Greenland and Abingdon. It has also had many narrow squeaks that have fortunately ended in safe but breathless and blood-chilling landings. It has killed thirteen and injured many others.

The Hermes has been involved in at least nine accidents in the past two years, some of which have been fatal.

These machines, both the Hastings and the Hermes, share many odd and lethal vices among which shedding propellers – which most pilots find a handicap – has been noticeable.

How much longer do these four-[text missing]

[boxed with picture] CASSANDRA SAYS:

[italics] "Why this earth-attracted brute is not grounded, I do not know." [/boxed]

[page break]

[columns] a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h. [/columns]

[a] 8.12.50 [b] 09.05 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Lyneham – Castel Benito [g] 6.50

[a] 9.12.50 [b] 04.00 [c] TG530 [d] F/Lt Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Castel Benito – Fayid [g] 5.00

[a] 9.12.50 [b] 11.55 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Fayid – Habbaniya [g] 2.50 [h] 1.00

[a] 10.12.50 [b] 04.15 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya - Mauripur [g] 7.10

[a] 11.12.50 [b] 01.55 [c] TG530 [d] F/LT Hanson [e] Passenger [f] Mauripor – Megombo [g] 7.10

[a] 15.12.50 [b] 04.50 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Foster [e] Engineer [f] Megombo – Changi [g] 6.20 [h] 2.00

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 02.40 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Foster [e] Engineer [f] Changi – Megombo [g] 8.00

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 13.10 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Stafford [e] Passenger [f] Mecombo - Mauripor [h] 6.40

[a] 18.12.50 [b] 22.35 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Davenport [e] Passenger [f] Mauripor – Habbaniya [g] 2.00 [h] 5.35

[a] 19.12.50 [b] 12.15 [c] TG574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya – El Adem No 2 Eng U/S. [g] .45

[a] 20.12.50 [b] 08.45 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] Habbaniya - El Adem [g] 5.50

[a] 20.12.50 [b] 18.00 [c] TG.574 [d] F/LT Tunnadine [e] Passenger [f] El Adem – Bennina CRASH LANDED [h] 1.50

[a] 24.12.50 [b] 08.15 [c] TG [deleted] 514 [/deleted][inserted] 526 [/inserted] [d] F/O Perrin [e] Passenger [f] Bennina - Castel Benito [g] 215

TOTAL TIME ... [g] 967.40 [h]348.35

Collection

Citation

Cole Christopher & Grant Roderick:, “Fate Deals a Blow,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 26, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/36338.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.