Bring 'Em Back Alive

Title

Bring 'Em Back Alive

Description

The story of how aircrew were supplied with clothing and material to help them escape and evade capture. It is written by the major that designed the items.

Creator

Date

1960-07

Language

Type

Format

Two newspaper pages

Conforms To

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

MHayhurstJM2073102-170725-160001, MHayhurstJM2073102-170725-160002

Transcription

10 [underlined] WEEKEND, July 27-31, 1960 [/underlined]

[underlined] The man the R.A.F. didn’t want got our boys home from the prison camps by using buttons, brown paper, razor blades, boot laces . . . and amazing ingenuity. The War Office tried to ban his story. But now, at last, you can read how he did it [/underlined]

[black and white head and shoulders photograph of Clayton Hutton]

CLAYTON HUTTON. World War I pilot, barged his way into the Army in 1939 and was made a back-room boy – master-minding the tools of escape, espionage and terror. But some people called him a crook

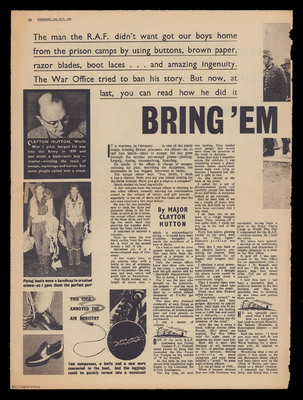

[black and white photograph of two airmen wearing flying gear]

Flying boots were a handicap to crashed crews – so I gave them the perfect pair

[three black and white photographs of shoes]

THIS IDEA ANNOYED THE AIR MINISTRY

Two compasses, a knife and a saw were concealed in the boot. And the leggings could be quickly turned into a waistcoat

BRING ‘EM

By MAJOR CLAYTON HUTTON

IT is wartime, in Germany . . . in one of the many camps housing British prisoners. An officer – let us call him Smith – plans to escape. He has gone through the normal pre-escape phase – plotting, forging, dyeing, reconnoitring, hoarding.

He speaks to the officer in charge of escapes, outlining his plan, describing the equipment, the documents he has begged, borrowed or stolen.

The escape officer says: “Yes, Smith, I think it has a chance. Now, you say you intend making for the Swiss frontier. Have you got a map or a compass?”

Smith shakes his head regretfully.

A few minutes later the escape officer is chatting to two other officers, casually steering the conversation round to the subject of letters and gift parcels – especially to the set of darts and the chess set that the two men received a few days before.

He asks the two mystified men to fetch the darts and chessmen along to his hut. Then, as soon as he is alone, the escape officer takes one of the three darts, and holding the metal band that encircles the wooden shaft, twists the body clockwise.

It unscrews to uncover a compass.

Next he takes the two black castles from the chess set. A twist on the second reveals a ball of silk.

Smoothed out, it is a seven-coloured map of Germany.

A few nights later, as the sentries relax with a bottle or two of schnapps, Smith makes his getaway. And in his pocket – the compass and map which will guide him to Switzerland.

Had Smith wanted, say, a length of piano wire – which is extraordinarily strong – it would have been available. Smuggled in inside the waistband of a pair of slacks.

Or a lens to read the more minute details on a map. This may have been disguised as a stopper to a bottle of brilliantine.

Only the escape officer knew that these aids were in the camp – smuggled in with the gift parcels sent by “charitable organisations.”

But at home, I knew too. For I was the man who thought up the gimmicks, the gadgets – and the ways and means of smuggling them in – which helped thousands of P.o.Ws get back home.

The man who dreamed constantly of such things as cigarette-packet-sized radios and cameras, of fountain-pen guns and trick pencils to help our spies and resistance movements.

I was a master of trickery

[drawing of a prison camp fence]

ONE of my early R.A.F. customers was Group Captain P.C. Pickard, better known by those who remember the film Target For Tonight as the captain of “F for Freddie.”

At this time he was connected with clandestine night flights to the Continent for British Intelligence.

The big snag, he said, was landing. They needed some gadget that would show them the direction of the wind in darkness.

Some days later I stumbled across the solution. I was wandering around a plastic factory where newly-made tennis balls were lying on benches. I bounced one idly and it split in two.

An idea stirred at the back of my mind.

I called for a pot of phosphorescent paint, and carefully coated the insides of six half-balls. A workman looked at me curiously.

Had he been able to see me a couple of hours later with the half-balls he would have been convinced that I was mad.

I set them out on my lawn in a rough hexagon shape. Then, waiting till it was quite dark, I made my way up to the roof of the building.

Forty feet below, glowing visibly on the lawn, were my six “fairy lights.” Pickard’s problem was solved.

Next day I was back at the plastics factory, consulting the experts. They quickly produced for me bigger and tougher half-balls.

I obtained a more powerful luminous paint, and experimented till I thought the plastic bowls would be visible at night from a considerable height.

Then I handed them over to Pickard, and asked him to let me know the result.

Three days later Pickard called on me.

“Absolutely wizard,” he enthused. “I had your gadgets delivered by special plane. Next night one of my pilots flew over the landing zone at 1,000 feet and could see it distinctly – a ruddy great arrow pointing out the direction of the wind.”

After the war I wrote a book, Official Secrets (Max Parrish, 18s) about my exploits. The War Office tried for eight years to suppress my story – and lost.

How did it start, this business of my becoming the O.C. of peculiar gadgets to the Services, defying authority on many occasions, and even being labelled a “crook” by some high-ranking officers.

Let me go back to 1939 . . .

When it became obvious that war with Germany was inevitable, having been a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps in World War One I volunteered for the R.A.F. – without success. So I tried the Army.

My letters were ignored. I decided on an unorthodox approach, and dispatched 17 lengthy telegrams in a week to the War Office.

It paid off. I was summoned to the War Office for an appointment with a Major J.H. Russell, who told me: “My job is to fit square pegs into round holes. Tell me all about yourself.”

I told him how I had been a journalist, then a publicity director in the film business, and that my speciality was in thinking up new ideas and putting them across.

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

HE was specially interested when I told him how, as a youngster, I had tried to outwit Houdini, the famous illusionist, at Birmingham Empire – and failed.

Said the major: “I think you may very well fit into one of our square holes. We’re looking for a showman with an interest in escapology.”

Wondering what it was all about, I was taken to the old Metropole Hotel, which had been taken over by the Office of Works, and introduced to a Major Crockatt.

I repeated my Houdini story, and found that I was

[page break]

BACK ALIVE!

WEEKEND EXCLUSIVE

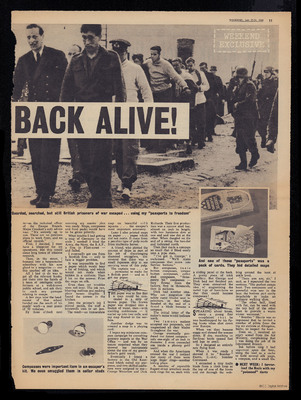

[black and white photograph of prisoners of war being marched along the road by German soldiers]

Guarded, searched, but still British prisoners of war escaped . . . using my “passports to freedom”

[black and white photograph of playing cards]

And one of those “passports” was a pack of cards. They hid detailed maps

in – as the technical officer of the Escape Branch. Major Crockatt’s only advice was: “It’s entirely up to you. There are no previous plans to work from, and no official records.”

First, I decided, I must have a blueprint for my operations. But this would mean long hours of irksome research.

Then, in the street, I bumped into a bespectacled schoolboy with his eyes glued to a magazine – and this sparked off an idea.

All I had to do was to get all the relevant books, put them into the hands of a team of intelligent sixth-formers at a well-known public school, and ask them to mark any passages relating to escape.

A few days later the headmaster of that school handed me the result of his pupils’ work – a neat precis of 50 volumes.

By three o’clock next morning my master plan was ready. Maps, compasses and food packs would have to be given priority.

What trouble I had getting a map of Germany to the scale I needed! I tried the Army, the Navy, the R.A.F., a firm in Fleet-street – and failed.

I eventually got one from a Scottish firm – only to face a bigger problem.

It was impossible to find a paper which would bear a lot of folding, and which would not rustle when hidden in a uniform. Then I hit on the answer. Print the maps on silk.

Even then my troubles were not over. The ink ran, blurring outlines and making place names illegible. I found the answer in the kitchen.

Into the printer’s ink I stirred pectin, the stuff a housewife uses to set jam.

The result – an immaculate map on beautiful silk squares . . . the escaper’s most important accessory.

Later I also printed maps on paper . . . paper which did not rustle. It came from a peculiar type of pulp made from mulberry leaves.

A friend, who plotted the courses of ships as part of his job of discouraging diamond smugglers, discovered that there was a small Japanese ship at sea carrying some of this pulp.

The captain was . . . er . . . persuaded to make for a British port – and so I got my paper.

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

THE paper was so fine that a map could be concealed in a strip of brown paper. The brown paper was dropped into a bucket of water, then – with startling suddenness – it curled up into two coils, and my map floated to the surface.

Another dodge was to conceal a map in a playing card.

I began my miniature compass campaign by consulting gunnery experts at the War Office – and was by no means surprised when they showed me instruments about the size of my grandfather’s gold watch.

Eventually I found a factory in the Old Kent-road which suited my purposes, and two skilled craftsmen were assigned to me – George Waterlow and Dick Richards. Their first production was a narrow steel bar, almost an inch in length, with two luminous dots at one end and one dot at the other. When dangled on the end of a string, the two-dot end indicated north.

Then they made a compass so small that it fitted easily into a pipe stem.

“I’ve got it, George,” I exclaimed. “We’ll make compasses that screw into Service Buttons.”

Bar compasses, tunic button compasses, trouser button compasses, collar stud compasses, “threepenny bit” compasses – they flowed from the factory, first in thousands, then in millions.

Dick had another idea. Why not magnetize the safety razor blades sent to prisoners, so that when dangled at the end of a thread a blade became a compass.

The initial letter of the maker’s name would indicate north.

Two famous makers accepted our proposals, and magnetized all their blades throughout the war.

George eventually produced our tiniest compass – only one-eight of an inch in diameter. I even concealed one inside a phoney gold tooth!

And when the Americans entered the war I noticed that many of them wore large finger rings – another hiding place.

A number of reputable Regent-street jewellers made such rings for us, each with a sliding panel at the back. A pretty piece of trick jewellery. But George and Dick had not finished yet. They even conceived the idea of magnetizing the metal tags of boot-laces so that they could become compasses!

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

SPEAKING about boots, many a young flier complained that he was handicapped by his flying boots when shot down over Europe.

When wet they became soggy and slowed the wearer down. If dry, marching in fur-lined boots caused feet and legs to swell.

So I designed an entirely new flying boot.

When it was ready I showed it to “Bomber” Harris, C.-in-C. Bomber Command.

I extracted a tiny knife blade from a cloth loop at the top of one of the boots and cut through the webbing around the boot at ankle level.

“There you are, sir,” I said, as I separated the two sections. “The perfect escape boot. Two compasses and a powerful wire saw in the lace; the bottom part easily detachable to make an ordinary walking shoe.

“The other half, lined with fur, can be used with the top half of the other boot to provide a warm winter waistcoat.”

“Bomber” Harris was so impressed that he invited a number of pilots from the big air stations at Abingdon, Berks, to inspect the boot.

Even so, I received an angry screed from the Air Ministry, complaining that I was doing the job of its Equipment Branch.

But before long I had improved upon the boot, using the heel as a cache to hold several silk maps, a compass, and a small file.

[symbol] NEXT WEEK: I terrorized the Nazis with my “poisoned” darts

[black and white photograph of collar studs]

Compasses were important item in an escaper’s kit. We even smuggled them in collar studs

[underlined] The man the R.A.F. didn’t want got our boys home from the prison camps by using buttons, brown paper, razor blades, boot laces . . . and amazing ingenuity. The War Office tried to ban his story. But now, at last, you can read how he did it [/underlined]

[black and white head and shoulders photograph of Clayton Hutton]

CLAYTON HUTTON. World War I pilot, barged his way into the Army in 1939 and was made a back-room boy – master-minding the tools of escape, espionage and terror. But some people called him a crook

[black and white photograph of two airmen wearing flying gear]

Flying boots were a handicap to crashed crews – so I gave them the perfect pair

[three black and white photographs of shoes]

THIS IDEA ANNOYED THE AIR MINISTRY

Two compasses, a knife and a saw were concealed in the boot. And the leggings could be quickly turned into a waistcoat

BRING ‘EM

By MAJOR CLAYTON HUTTON

IT is wartime, in Germany . . . in one of the many camps housing British prisoners. An officer – let us call him Smith – plans to escape. He has gone through the normal pre-escape phase – plotting, forging, dyeing, reconnoitring, hoarding.

He speaks to the officer in charge of escapes, outlining his plan, describing the equipment, the documents he has begged, borrowed or stolen.

The escape officer says: “Yes, Smith, I think it has a chance. Now, you say you intend making for the Swiss frontier. Have you got a map or a compass?”

Smith shakes his head regretfully.

A few minutes later the escape officer is chatting to two other officers, casually steering the conversation round to the subject of letters and gift parcels – especially to the set of darts and the chess set that the two men received a few days before.

He asks the two mystified men to fetch the darts and chessmen along to his hut. Then, as soon as he is alone, the escape officer takes one of the three darts, and holding the metal band that encircles the wooden shaft, twists the body clockwise.

It unscrews to uncover a compass.

Next he takes the two black castles from the chess set. A twist on the second reveals a ball of silk.

Smoothed out, it is a seven-coloured map of Germany.

A few nights later, as the sentries relax with a bottle or two of schnapps, Smith makes his getaway. And in his pocket – the compass and map which will guide him to Switzerland.

Had Smith wanted, say, a length of piano wire – which is extraordinarily strong – it would have been available. Smuggled in inside the waistband of a pair of slacks.

Or a lens to read the more minute details on a map. This may have been disguised as a stopper to a bottle of brilliantine.

Only the escape officer knew that these aids were in the camp – smuggled in with the gift parcels sent by “charitable organisations.”

But at home, I knew too. For I was the man who thought up the gimmicks, the gadgets – and the ways and means of smuggling them in – which helped thousands of P.o.Ws get back home.

The man who dreamed constantly of such things as cigarette-packet-sized radios and cameras, of fountain-pen guns and trick pencils to help our spies and resistance movements.

I was a master of trickery

[drawing of a prison camp fence]

ONE of my early R.A.F. customers was Group Captain P.C. Pickard, better known by those who remember the film Target For Tonight as the captain of “F for Freddie.”

At this time he was connected with clandestine night flights to the Continent for British Intelligence.

The big snag, he said, was landing. They needed some gadget that would show them the direction of the wind in darkness.

Some days later I stumbled across the solution. I was wandering around a plastic factory where newly-made tennis balls were lying on benches. I bounced one idly and it split in two.

An idea stirred at the back of my mind.

I called for a pot of phosphorescent paint, and carefully coated the insides of six half-balls. A workman looked at me curiously.

Had he been able to see me a couple of hours later with the half-balls he would have been convinced that I was mad.

I set them out on my lawn in a rough hexagon shape. Then, waiting till it was quite dark, I made my way up to the roof of the building.

Forty feet below, glowing visibly on the lawn, were my six “fairy lights.” Pickard’s problem was solved.

Next day I was back at the plastics factory, consulting the experts. They quickly produced for me bigger and tougher half-balls.

I obtained a more powerful luminous paint, and experimented till I thought the plastic bowls would be visible at night from a considerable height.

Then I handed them over to Pickard, and asked him to let me know the result.

Three days later Pickard called on me.

“Absolutely wizard,” he enthused. “I had your gadgets delivered by special plane. Next night one of my pilots flew over the landing zone at 1,000 feet and could see it distinctly – a ruddy great arrow pointing out the direction of the wind.”

After the war I wrote a book, Official Secrets (Max Parrish, 18s) about my exploits. The War Office tried for eight years to suppress my story – and lost.

How did it start, this business of my becoming the O.C. of peculiar gadgets to the Services, defying authority on many occasions, and even being labelled a “crook” by some high-ranking officers.

Let me go back to 1939 . . .

When it became obvious that war with Germany was inevitable, having been a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps in World War One I volunteered for the R.A.F. – without success. So I tried the Army.

My letters were ignored. I decided on an unorthodox approach, and dispatched 17 lengthy telegrams in a week to the War Office.

It paid off. I was summoned to the War Office for an appointment with a Major J.H. Russell, who told me: “My job is to fit square pegs into round holes. Tell me all about yourself.”

I told him how I had been a journalist, then a publicity director in the film business, and that my speciality was in thinking up new ideas and putting them across.

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

HE was specially interested when I told him how, as a youngster, I had tried to outwit Houdini, the famous illusionist, at Birmingham Empire – and failed.

Said the major: “I think you may very well fit into one of our square holes. We’re looking for a showman with an interest in escapology.”

Wondering what it was all about, I was taken to the old Metropole Hotel, which had been taken over by the Office of Works, and introduced to a Major Crockatt.

I repeated my Houdini story, and found that I was

[page break]

BACK ALIVE!

WEEKEND EXCLUSIVE

[black and white photograph of prisoners of war being marched along the road by German soldiers]

Guarded, searched, but still British prisoners of war escaped . . . using my “passports to freedom”

[black and white photograph of playing cards]

And one of those “passports” was a pack of cards. They hid detailed maps

in – as the technical officer of the Escape Branch. Major Crockatt’s only advice was: “It’s entirely up to you. There are no previous plans to work from, and no official records.”

First, I decided, I must have a blueprint for my operations. But this would mean long hours of irksome research.

Then, in the street, I bumped into a bespectacled schoolboy with his eyes glued to a magazine – and this sparked off an idea.

All I had to do was to get all the relevant books, put them into the hands of a team of intelligent sixth-formers at a well-known public school, and ask them to mark any passages relating to escape.

A few days later the headmaster of that school handed me the result of his pupils’ work – a neat precis of 50 volumes.

By three o’clock next morning my master plan was ready. Maps, compasses and food packs would have to be given priority.

What trouble I had getting a map of Germany to the scale I needed! I tried the Army, the Navy, the R.A.F., a firm in Fleet-street – and failed.

I eventually got one from a Scottish firm – only to face a bigger problem.

It was impossible to find a paper which would bear a lot of folding, and which would not rustle when hidden in a uniform. Then I hit on the answer. Print the maps on silk.

Even then my troubles were not over. The ink ran, blurring outlines and making place names illegible. I found the answer in the kitchen.

Into the printer’s ink I stirred pectin, the stuff a housewife uses to set jam.

The result – an immaculate map on beautiful silk squares . . . the escaper’s most important accessory.

Later I also printed maps on paper . . . paper which did not rustle. It came from a peculiar type of pulp made from mulberry leaves.

A friend, who plotted the courses of ships as part of his job of discouraging diamond smugglers, discovered that there was a small Japanese ship at sea carrying some of this pulp.

The captain was . . . er . . . persuaded to make for a British port – and so I got my paper.

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

THE paper was so fine that a map could be concealed in a strip of brown paper. The brown paper was dropped into a bucket of water, then – with startling suddenness – it curled up into two coils, and my map floated to the surface.

Another dodge was to conceal a map in a playing card.

I began my miniature compass campaign by consulting gunnery experts at the War Office – and was by no means surprised when they showed me instruments about the size of my grandfather’s gold watch.

Eventually I found a factory in the Old Kent-road which suited my purposes, and two skilled craftsmen were assigned to me – George Waterlow and Dick Richards. Their first production was a narrow steel bar, almost an inch in length, with two luminous dots at one end and one dot at the other. When dangled on the end of a string, the two-dot end indicated north.

Then they made a compass so small that it fitted easily into a pipe stem.

“I’ve got it, George,” I exclaimed. “We’ll make compasses that screw into Service Buttons.”

Bar compasses, tunic button compasses, trouser button compasses, collar stud compasses, “threepenny bit” compasses – they flowed from the factory, first in thousands, then in millions.

Dick had another idea. Why not magnetize the safety razor blades sent to prisoners, so that when dangled at the end of a thread a blade became a compass.

The initial letter of the maker’s name would indicate north.

Two famous makers accepted our proposals, and magnetized all their blades throughout the war.

George eventually produced our tiniest compass – only one-eight of an inch in diameter. I even concealed one inside a phoney gold tooth!

And when the Americans entered the war I noticed that many of them wore large finger rings – another hiding place.

A number of reputable Regent-street jewellers made such rings for us, each with a sliding panel at the back. A pretty piece of trick jewellery. But George and Dick had not finished yet. They even conceived the idea of magnetizing the metal tags of boot-laces so that they could become compasses!

[black and white drawing of a prison camp fence]

SPEAKING about boots, many a young flier complained that he was handicapped by his flying boots when shot down over Europe.

When wet they became soggy and slowed the wearer down. If dry, marching in fur-lined boots caused feet and legs to swell.

So I designed an entirely new flying boot.

When it was ready I showed it to “Bomber” Harris, C.-in-C. Bomber Command.

I extracted a tiny knife blade from a cloth loop at the top of one of the boots and cut through the webbing around the boot at ankle level.

“There you are, sir,” I said, as I separated the two sections. “The perfect escape boot. Two compasses and a powerful wire saw in the lace; the bottom part easily detachable to make an ordinary walking shoe.

“The other half, lined with fur, can be used with the top half of the other boot to provide a warm winter waistcoat.”

“Bomber” Harris was so impressed that he invited a number of pilots from the big air stations at Abingdon, Berks, to inspect the boot.

Even so, I received an angry screed from the Air Ministry, complaining that I was doing the job of its Equipment Branch.

But before long I had improved upon the boot, using the heel as a cache to hold several silk maps, a compass, and a small file.

[symbol] NEXT WEEK: I terrorized the Nazis with my “poisoned” darts

[black and white photograph of collar studs]

Compasses were important item in an escaper’s kit. We even smuggled them in collar studs

Collection

Citation

Weekend Newspaper, “Bring 'Em Back Alive,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 22, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/35975.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.