Your Place in the Air Crew Team

Title

Your Place in the Air Crew Team

Description

A booklet issued to RAF volunteers on arrival at a Receiving Centre. It summarises what is about to happen to the volunteer.

Creator

Date

1944-04

Coverage

Language

Format

16 page printed booklet

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050001, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050002, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050003, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050004, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050005, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050006, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050007, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050008, MLeadbetterJ163970-160421-050009

Transcription

YOUR PLACE in the AIR CREW TEAM

[photograph]

A.M. PAMPHLET 167 A.M.T. 13

[page break]

A. M. PAMPHLET 167

FIRST EDITION APRIL 1944

For issue to cadets when they arrive at Air-Crew Receiving Centres

1. APTITUDE TESTS AND GRADING - - 1

2. AIR CREW DUTIES AND TRAINING - 9

[page break]

APTITUDE TESTS AND GRADING

THIS IS YOUR FIRST WEEK of service in the Royal Air Force. You have volunteered to fight as a member of one of the air-crew teams who carry on the war in the air. Now that you are actually starting your training the first, most important problem which has to be settled is that of deciding your air crew category. The purpose of this pamphlet is to tell you something of the methods the Service is going to use to make sure that you are classified for training in the air crew category for which you are best fitted and most needed.

There have been times when the war in the air was a battle between individuals, each using his own aircraft as a weapon with which to fight ; but, as you know, in this war the air battle is largely fought by teams operating large and complicated aircraft, and not by individual pilots. In a large modern aircraft there are many different jobs to be done, and each must be done quickly and efficiently by specially-trained men.

The air-crew team requires a pilot, and a highly-skilled specialist who can navigate accurately to and from the target. It also needs another specialist who can help to keep the engines and controls operating throughout the flight. It needs a number of specialists who can effectively protect the crew from attack by enemy aircraft. It needs a specialist in radio-communication work. It needs a specialist who, when the target area is reached, can make sure that the bombs are well and truly aimed.

Success, then, depends on the efficiency of teams of specialists, each using, as a member of a co-ordinated team, the particular skill he acquired in training. From this it is clear that, just as in football everybody cannot be a centre-forward or a half-back, so in modern warfare everyone cannot be a pilot. Instead we have to develop air-crew teams in which each man is engaged in the specialist job he can do best ; and it is therefore the task and duty of the R.A.F. to make sure that each one of you shall, as far as possible, start air-crew training in the category in which you are likely to be most successful.

[page break]

2

What are you going to be?

The problem of finding the best air-crew for you is not simple. Your category cannot be decided wholly in terms of what you want to be, nor even in terms of what you are best fitted to be, although both these factors are important. There is another factor which must be considered before either of these, and that is the needs of the Service. The Royal Air Force must have air crew trained in the proper proportions to man its operational aircraft.

Your Selection Board saw that you are the sort of man the R.A.F. wants, in broad terms, as a member of an air-crew. Now that your training is about to start, the Service is in a better position to determine in what air-crew capacity you will be most effective : for the immediate air-crew needs of the Service are more precisely known; a great deal of research has made is possible to measure more accurately your suitability for each air-crew category; and finally, you are in a better position to say what you want to be.

Finding your category

The following facts, then, will determine the air-crew category for which you will be trained.

[italics] 1. The needs of the Service (What does the R.A.F. require?) [/italics] If it is to meet its fighting requirements, the Service must see that it classifies and trains air crew in the right proportions needed to man its fighting aircraft, and the future air-crew needs of the R.A.F. are, accordingly, forecast a considerable time ahead. This means that the men entering air-crew training each week are needed in known proportions for the air-gunner category, the pilot category and so on. So this is the first consideration which will influence your classification : what are the operational needs of the R.A.F.?

[italics] 2. Your special aptitude (What are you best fitted for?) [/italics] In its classification work the Service also considers it important to take careful account of any special aptitude you have for one or other of the air-crew categories. For, from both the R.A.F. and the cadet's point of view, it would be wasteful and inefficient to classify a cadet in a category for which he has little or no aptitude, or to ignore evidence of a marked aptitude he has for a particular category.

Therefore you will be given a series of perfectly straightforward air-crew aptitude tests to guage [sic] your skill in solving the sort of

[page break]

3

problems you will meet in training. The results then serve to show whether you have enough [italics] special ability [/italics] for the category that will finally be chosen for you as an outcome of these tests and of the other factors mentioned.

[italics] 3. Your interest (What do you want to be?) [/italics] Many of you already have a preference for service in a particular air-crew category. This is recognized by the Service as important, for it is realized that, in a general way, a man is likely to work hardest at that in which he is most interested. You will, therefore, be asked to state your degrees of interest in the six basic air-crew categories (air bomber ; air gunner ; flight engineer ; navigator ; pilot ; wireless-operator air). So find out from your Flight Commander all you can about these categories and decide early what your relative interests are.

It is well to face this business of personal preference realistically. First the needs of the Service are considered ; then your suitability for various categories ; and then, if you are found to have sufficient aptitude for two or more categories, your personal choice. For example, suppose you are found to have enough aptitude to become either a navigator or an air bomber and you would rather become an air-bomber. Then – provided cadets with even greater aptitude for air bomber training are not available to fill the vacancy – you will be classified for training as an air bomber. Indeed, even if you showed a greater aptitude for navigating than for bomb-aiming, your wish to become an air bomber will still be seriously entertained if the air bomber training vacancies warrant it.

A special word is necessary to those who would prefer, above all else, to become pilots. Most of you could probably be taught to fly a Moth, but only about one cadet in four is found to have the really high degree of aptitude which the Service now requires of those entering pilot-training. This high natural aptitude is something with which one either is or is not born ; it is not a matter of intelligence, and it cannot be acquired by dint of trying. So if you want to become a pilot and yet do not achieve your wishes, do not regard it as a discredit, but strive instead to make full use of the special aptitude you have for the category to which you are appointed for training.

The importance of stating accurately your relative interests in the various air-crew categories should now, therefore, be apparent to you. So find out all you can about them, and be frank about your preferences when you are asked to state them, To help you

[page break]

4

make up your mind, the last section of this pamphlet tells you something about the training and duties of the six basic air-crew categories.

What happens now?

You have entered the R.A.F. to become a member of one of the air-crew teams which are to carry on the war in the air. To begin your training, you have entered an Air-Crew Receiving Wing (A.C.R.C.), where you will stay for six weeks. During the first two weeks you will be registered, medically examined and kitted. In the third week your air-crew aptitude tests will take place. And throughout your stay at A.C.R.C. you will receive basic training in drill, discipline, R.A.F. law, administration and organization, and in mathematics, signals, and the use of weapons. You will also play organized games, do physical training and, if you cannot already swim, receive swimming lessons. All this, as you are probably aware, is general service training to fit you for the job that lies ahead.

What are these aptitude tests?

Two full days are given to air crew aptitude testing. Most tests are of the pencil-and-paper kind, which you take at a desk or table in a room with a large number of other cadets. Some tests, which employ apparatus, are taken in smaller groups ; these tests measure the speed with which you can learn to manipulate controls and gadgets resembling those found in an aircraft.

The aptitude tests measure such things as your quickness to learn, the ease with which you solve mathematical problems, the accuracy and speed with which you observe things, your understanding of everyday mechanical problems, and your capacity to learn to perform tasks which require eye-hand-foot co-ordination.

You will receive all these tests in exactly the same manner, and in about the same order, as all other cadets in your draft. Your scores will be determined entirely by what [italics] you [/italics] do. Nobody watches to note what your 'reactions' are. Those who are doing the testing are there solely to see that you understand and follow instructions, and-so that each has a perfectly fair chance to show exactly what he can do – to make sure that all cadets do receive the same tests in the same way.

Most of the tests have a time limit, and you are required to work as fast as you can. Do not imagine for one moment that this is

[page break]

5

unfair. Nobody is interested in what you could do if you had unlimited time. In training you will have to learn quickly, and it is your ability to do this that is being assessed. Most tests include problems easy enough for nearly everybody to solve, but they also include problems that very few can solve in the time allowed. Do not let this surprise you, and do not expect to get a perfect score. Simply [italics] make sure that you get the best score you are capable of [/italics] in the time allowed.

Nothing about these tests need worry you, and there is no preparation you can or need make for them. You should know, also, that the tests cannot be manipulated, even if you wished to do so. Each test has a dual or multiple purpose so that by it your aptitude for more than one air-crew category can be measured. Do not be misled by the superficial appearance of some of the tests. For example, a test with aerial photographs may seem to you to be a test of a navigator aptitude, and one involving the manipulation of what looks like an air gunner's turret to be a measure of the co-ordination required to be an air-gunner. So they are, but the former is also a measure of pilot aptitude and the latter of pilot-co-ordination ability.

Again, do not worry about doing too well on any test for fear of missing a category you really want. Nor should you worry if you do rather badly in any particular test. The tests cover a wide range, and for that reason it is to be expected that you will do well on some and poorly on others ; indeed, they are designed to disclose what are your [italics] special [/italics] strengths and weaknesses. Also no one test counts for very much by itself ; if you do badly in a test, you will find that you get another chance in some other test later on.

If you feel you want to, there is no harm in questioning others who have taken the tests before ; but you are not likely to learn very much of value, because there are so many tests that you will probably find the answers more confusing than helpful. Remember what the tests are for – to give the Service a measure of your present skill and aptitude. You can do nothing now to make either appear better than they really are ; the only mistake you can make is to have them appear lower. So regard it as your job to do the best you can with each test as you come to it, and remember that after the results are assessed your personal preferences will be given full consideration.

Before you start the tests, be sure that you are physically well. If you feel unfit, it is your responsibility to tell your Flight

[page break]

6

Commander so. If necessary he can then have your tests and classification postponed until you are fit again ; but under no circumstances can you take the tests a second time.

And then?

After the tests you will continue your general service training, and during the last week at the A.C.R.C. your Flight Commander will tell you the air-crew category in which you have been placed. [italics] That [/italics] is going to be your position in the air-crew team. It is the best position for you, because it is the one for which you are most needed by the Service and to which you are best suited. It is also a category that you have chosen yourself from among the categories for which Service requirements plus the results of your tests have made you eligible.

On finishing the A.C.R.C. course you will either go to a Grading School and then on to an Initial Training Wing (I.T.W.) or you will go straight to an I.T.W. At the I.T.W. you will begin specialized training with other men of the same air-crew category.

There is approximately a fifty per cent. chance that after A.C.R.C. you will go to a Grading School. Some half of the cadets leaving A.C.R.C. at any given time have proved by their tests that they would be likely to do well in pilot-training. If you are one of these and have also stated the pilot category as your first choice, you will be given the chance of going to a Grading School. Here you will go through the initial stages of learning to fly. This process is called the Flight Test, and because the few hours of standard flying instruction is affords permit your subsequent performance to be predicted with a high degree of accuracy, the R.A.F. uses it to determine finally who shall be classified for full pilot-training.

So going to a Grading School does not [italics] necessarily [/italics] mean that you are going to be a pilot. It simply means that you have shown enough promise to justify the Service in now giving you an expensive but very effective aptitude test, so that it may be able to judge, from actual performance in the air, who are most eligible for pilot training within the quota allowed.

Before leaving A.C.R.C. for a Grading School, you are told what your alternative air-crew category will be if you do not secure a pilot classification. In going to grading, you must understand that you are being given a full chance to show the degree of natural aptitude you have to learn to fly, and that you are quite

[page break]

7

prepared to serve in the alternative category if it turns out that you are less apt as a pilot than others. Finally, remember that not to qualify for pilot-training does not mean that you have failed ; it means that you showed promise and justified the use of a test which could not be given at A.C.R.C.

After I.T.W.?

If you qualify at the I.T.W. for the category that has been chosen for you, at the end of the course you will be given 7 days' leave, with pay and a free travel-warrant to your leave address. After leave, your next movements are as follows :

AIR BOMBERS, NAVIGATORS, PILOTS }

A few who are to be trained in the United Kingdom are posted to units here. The great majority go to an Air-Crew Despatch Centre (A.C.D.C.) to await posting overseas to continue their training.

WIRELESS OPERATORS (AIR) }

To a Technical Training School in the United Kingdom for a specialized Signals Course. Subsequent training is then done either in the United Kingdom or overseas.

FLIGHT ENGINEERS }

To a Technical Training School in the United Kingdom.

AIR GUNNERS }

To Air Gunnery Schools in the United Kingdom.

Fuller details about these later training stages are given at the end of this pamphlet. Do not hesitate to ask your Flight Commander if you want to know still more about them.

Delays

In conclusion, just a few words about delays that may occur between successive stages of your training.

Everything humanly possible is done to prevent delays, but if you find that you have to wait between training courses, remember that in a war of this gigantic size and scope it is not always possible to keep training running neatly and smoothly to a standard blueprint schedule. If there were no enemy, this might be possible ; but there is an enemy, and this means that a training organizatoin (sic) belonging to a fighting machine must be able to change to meet

[page break]

8

new situations as they arise. For example, intakes and training courses are planned to match the likely strategy and tactics of the United Nations and the enemy in some eighteen months' time. Then shipping movements, production difficulties, changes in operational requirements and a score of other factors may well alter the plans ; and as one of the direct results you may find yourself waiting at a Despatch or Reception Centre, impatient to go on to the next stage of training.

If you are held up, make the best of it. Your understanding and co-operation are worth ten times all the grumbling. Learn what you can while waiting. Take part with enthusiasm in all the recreation that comes your way ; and keep cheerful – it will help a great deal to keep the other fellows cheerful too.

[page break]

9

AIR-CREW DUTIES AND TRAINING

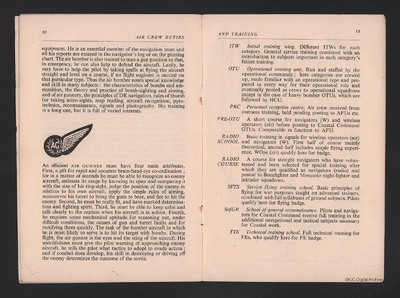

EARLIER IN THIS PAMPHLET you were promised that the last section would tell you something about the duties and training of the six basic air-crew categories. This is it. First, there is a brief description of the duties of each category, in alphabetical order ; possibly you will find that none of the jobs is as simple as you may have thought. Then there is a plan of the whole system of training ; all categories come together at A.C.R.C. and nearly all will come together again before training is complete. But in the meantime you will be sent many different ways ; if you are interested in what is likely to happen in each case, the diagram will help you. And at the end there is a brief explanation of the nature and purpose of each of the schools and courses that is shown in it.

When reading this section, remember that the training phases, course-names and the like are those in force now. This means that in some cases you may reach a training stage in several months' time to find that arrangements differ from those described here. Some of the reasons for changes occurring in the training plan have been given on pages 7 and 8.

[Air Bomber brevet]

THE AIR BOMBER has such varied duties that his is one of the most interesting jobs in a squadron. As his name implies, his main responsibility is the actual bombing of the target ; the navigator brings the aircraft to the target area, then the air bomber takes over to direct the pilot over the target, identify the aiming point and bomb it. But he has other work to do during the rest of the trip ; throughout the whole flight he acts as the eyes of the navigator, map reading whenever possible and taking astro-sights, noting the weather and sometimes operation special wireless

[page break]

10

equipment. He is an essential member of the navigation team and all his reports are entered in the navigator's log or on the plotting chart. The air bomber is also trained to man a gun position so that, in emergency, he can also help to defend the aircraft. Lastly, he may have to help the pilot by taking spells at flying the aircraft straight and level on a course, if no flight engineer is carried on that particular type. Thus the air bomber needs special knowledge and skill in many subjects : the characteristics of bombs, and ammunition, the theory and practice of bomb-sighting and aiming, and of air gunnery, the principles of DR navigation, rules of thumb for taking auto-sights, map reading, aircraft recognition, pyrotechnics, reconnaissance, signals and photography. His training is a long one, but it is full of varied interests.

[Air Gunner brevet]

An efficient AIR GUNNER must have four main attributes. First, a gift for rapid and accurate brain-hand-eye co-ordination ; for in a matter of seconds he must be able to recognize an enemy aircraft, estimate its range by knowing its span and comparing it with the size of his ring-sight, judge the position of the enemy in relation to his own aircraft, apply the simple rules of aiming, manoeuvre his turret to bring the guns to bear, and fire to hit the enemy. Second, he must be really fit, and have marked determination and fighting spirit. Third, he must be able to keep calm and talk clearly to the captain when his aircraft is in action. Fourth, he requires some mechanical aptitude for reasoning out, under difficult conditions, the causes of gun and turret faults and for rectifying them quickly. The task of the bomber aircraft in which he is most likely to serve is to hit its target with bombs. During flight, the air gunner is the eyes and the sting of the aircraft. His watchfulness must give the pilot warning of approaching enemy aircraft, he tells the pilot what tactics to adopt to evade action ; and if combat does develop, his skill in destroying or driving off the enemy determines the outcome of the sortie.

[page break][missing pages]

15

[italics] ITW Initial training wing. [/italics] Different ITWs for each category. General service training combined with an introduction to subjects important in each category's future training.

[italics] OTU Operational training unit. [/italics] Run and staffed by the operational commands ; here categories are crewed up, made familiar with an operational type and prepared in every way for their operational role and eventually posted as crews to operational squadrons except in the case of heavy bomber OTUs, which are followed by HCU.

[italics] PRC Personnel reception centre. [/italics] Air crew received from overseas training, help pending posting to AFUs etc.

[italics] PRE-OTU [/italics] A short course for navigators (W) and wireless operators (air) before posting to Coastal Command OTUs. Comparable in function to AFU.

[italics] RADIO SCHOOL [/italics] Basic training in signals for wireless operators (air) and navigators (W). First half of course mainly theoretical, second half includes ample flying experience. WOps (air) qualify here for badge.

[italics] RADIO COURSE [/italics] A course for straight navigators who have volunteered and been selected for special training after which they are qualified as navigators (radio) and posted to Beaufighter and Mosquito night-fighter and intruder squadrons.

[italics] SFTS Service flying training school. [/italics] Basic principles of flying for war purposes taught on advanced trainers, combined with full syllabuses of ground subjects. Pilots qualify here for flying badge.

[italics] SofGR School of general reconnaissance. [/italics] Pilots and navigators for Coastal Command receive full training in the additional navigational and tactical subjects necessary for Coastal work.

[italics] TTS Technical training school. [/italics] Full technical training for FEs, who qualify here for FE badge.

[page break]

16

[system of training diagram]

492 Wt.59682-T2932 20,000 4/44 Gp.8 F. & C. Ltd.

[page break]

Prepared and Issued by

THE AIR MINISTRY

A M T

This pamphlet is RESTRICTED ; it is not to be shown to anyone outside the service, nor to be taken into the air

[page break]

[bird logo]

F.2915 Wt.59682 20,000 4/44 Gp.961 Fosh & Cross Ltd.

[photograph]

A.M. PAMPHLET 167 A.M.T. 13

[page break]

A. M. PAMPHLET 167

FIRST EDITION APRIL 1944

For issue to cadets when they arrive at Air-Crew Receiving Centres

1. APTITUDE TESTS AND GRADING - - 1

2. AIR CREW DUTIES AND TRAINING - 9

[page break]

APTITUDE TESTS AND GRADING

THIS IS YOUR FIRST WEEK of service in the Royal Air Force. You have volunteered to fight as a member of one of the air-crew teams who carry on the war in the air. Now that you are actually starting your training the first, most important problem which has to be settled is that of deciding your air crew category. The purpose of this pamphlet is to tell you something of the methods the Service is going to use to make sure that you are classified for training in the air crew category for which you are best fitted and most needed.

There have been times when the war in the air was a battle between individuals, each using his own aircraft as a weapon with which to fight ; but, as you know, in this war the air battle is largely fought by teams operating large and complicated aircraft, and not by individual pilots. In a large modern aircraft there are many different jobs to be done, and each must be done quickly and efficiently by specially-trained men.

The air-crew team requires a pilot, and a highly-skilled specialist who can navigate accurately to and from the target. It also needs another specialist who can help to keep the engines and controls operating throughout the flight. It needs a number of specialists who can effectively protect the crew from attack by enemy aircraft. It needs a specialist in radio-communication work. It needs a specialist who, when the target area is reached, can make sure that the bombs are well and truly aimed.

Success, then, depends on the efficiency of teams of specialists, each using, as a member of a co-ordinated team, the particular skill he acquired in training. From this it is clear that, just as in football everybody cannot be a centre-forward or a half-back, so in modern warfare everyone cannot be a pilot. Instead we have to develop air-crew teams in which each man is engaged in the specialist job he can do best ; and it is therefore the task and duty of the R.A.F. to make sure that each one of you shall, as far as possible, start air-crew training in the category in which you are likely to be most successful.

[page break]

2

What are you going to be?

The problem of finding the best air-crew for you is not simple. Your category cannot be decided wholly in terms of what you want to be, nor even in terms of what you are best fitted to be, although both these factors are important. There is another factor which must be considered before either of these, and that is the needs of the Service. The Royal Air Force must have air crew trained in the proper proportions to man its operational aircraft.

Your Selection Board saw that you are the sort of man the R.A.F. wants, in broad terms, as a member of an air-crew. Now that your training is about to start, the Service is in a better position to determine in what air-crew capacity you will be most effective : for the immediate air-crew needs of the Service are more precisely known; a great deal of research has made is possible to measure more accurately your suitability for each air-crew category; and finally, you are in a better position to say what you want to be.

Finding your category

The following facts, then, will determine the air-crew category for which you will be trained.

[italics] 1. The needs of the Service (What does the R.A.F. require?) [/italics] If it is to meet its fighting requirements, the Service must see that it classifies and trains air crew in the right proportions needed to man its fighting aircraft, and the future air-crew needs of the R.A.F. are, accordingly, forecast a considerable time ahead. This means that the men entering air-crew training each week are needed in known proportions for the air-gunner category, the pilot category and so on. So this is the first consideration which will influence your classification : what are the operational needs of the R.A.F.?

[italics] 2. Your special aptitude (What are you best fitted for?) [/italics] In its classification work the Service also considers it important to take careful account of any special aptitude you have for one or other of the air-crew categories. For, from both the R.A.F. and the cadet's point of view, it would be wasteful and inefficient to classify a cadet in a category for which he has little or no aptitude, or to ignore evidence of a marked aptitude he has for a particular category.

Therefore you will be given a series of perfectly straightforward air-crew aptitude tests to guage [sic] your skill in solving the sort of

[page break]

3

problems you will meet in training. The results then serve to show whether you have enough [italics] special ability [/italics] for the category that will finally be chosen for you as an outcome of these tests and of the other factors mentioned.

[italics] 3. Your interest (What do you want to be?) [/italics] Many of you already have a preference for service in a particular air-crew category. This is recognized by the Service as important, for it is realized that, in a general way, a man is likely to work hardest at that in which he is most interested. You will, therefore, be asked to state your degrees of interest in the six basic air-crew categories (air bomber ; air gunner ; flight engineer ; navigator ; pilot ; wireless-operator air). So find out from your Flight Commander all you can about these categories and decide early what your relative interests are.

It is well to face this business of personal preference realistically. First the needs of the Service are considered ; then your suitability for various categories ; and then, if you are found to have sufficient aptitude for two or more categories, your personal choice. For example, suppose you are found to have enough aptitude to become either a navigator or an air bomber and you would rather become an air-bomber. Then – provided cadets with even greater aptitude for air bomber training are not available to fill the vacancy – you will be classified for training as an air bomber. Indeed, even if you showed a greater aptitude for navigating than for bomb-aiming, your wish to become an air bomber will still be seriously entertained if the air bomber training vacancies warrant it.

A special word is necessary to those who would prefer, above all else, to become pilots. Most of you could probably be taught to fly a Moth, but only about one cadet in four is found to have the really high degree of aptitude which the Service now requires of those entering pilot-training. This high natural aptitude is something with which one either is or is not born ; it is not a matter of intelligence, and it cannot be acquired by dint of trying. So if you want to become a pilot and yet do not achieve your wishes, do not regard it as a discredit, but strive instead to make full use of the special aptitude you have for the category to which you are appointed for training.

The importance of stating accurately your relative interests in the various air-crew categories should now, therefore, be apparent to you. So find out all you can about them, and be frank about your preferences when you are asked to state them, To help you

[page break]

4

make up your mind, the last section of this pamphlet tells you something about the training and duties of the six basic air-crew categories.

What happens now?

You have entered the R.A.F. to become a member of one of the air-crew teams which are to carry on the war in the air. To begin your training, you have entered an Air-Crew Receiving Wing (A.C.R.C.), where you will stay for six weeks. During the first two weeks you will be registered, medically examined and kitted. In the third week your air-crew aptitude tests will take place. And throughout your stay at A.C.R.C. you will receive basic training in drill, discipline, R.A.F. law, administration and organization, and in mathematics, signals, and the use of weapons. You will also play organized games, do physical training and, if you cannot already swim, receive swimming lessons. All this, as you are probably aware, is general service training to fit you for the job that lies ahead.

What are these aptitude tests?

Two full days are given to air crew aptitude testing. Most tests are of the pencil-and-paper kind, which you take at a desk or table in a room with a large number of other cadets. Some tests, which employ apparatus, are taken in smaller groups ; these tests measure the speed with which you can learn to manipulate controls and gadgets resembling those found in an aircraft.

The aptitude tests measure such things as your quickness to learn, the ease with which you solve mathematical problems, the accuracy and speed with which you observe things, your understanding of everyday mechanical problems, and your capacity to learn to perform tasks which require eye-hand-foot co-ordination.

You will receive all these tests in exactly the same manner, and in about the same order, as all other cadets in your draft. Your scores will be determined entirely by what [italics] you [/italics] do. Nobody watches to note what your 'reactions' are. Those who are doing the testing are there solely to see that you understand and follow instructions, and-so that each has a perfectly fair chance to show exactly what he can do – to make sure that all cadets do receive the same tests in the same way.

Most of the tests have a time limit, and you are required to work as fast as you can. Do not imagine for one moment that this is

[page break]

5

unfair. Nobody is interested in what you could do if you had unlimited time. In training you will have to learn quickly, and it is your ability to do this that is being assessed. Most tests include problems easy enough for nearly everybody to solve, but they also include problems that very few can solve in the time allowed. Do not let this surprise you, and do not expect to get a perfect score. Simply [italics] make sure that you get the best score you are capable of [/italics] in the time allowed.

Nothing about these tests need worry you, and there is no preparation you can or need make for them. You should know, also, that the tests cannot be manipulated, even if you wished to do so. Each test has a dual or multiple purpose so that by it your aptitude for more than one air-crew category can be measured. Do not be misled by the superficial appearance of some of the tests. For example, a test with aerial photographs may seem to you to be a test of a navigator aptitude, and one involving the manipulation of what looks like an air gunner's turret to be a measure of the co-ordination required to be an air-gunner. So they are, but the former is also a measure of pilot aptitude and the latter of pilot-co-ordination ability.

Again, do not worry about doing too well on any test for fear of missing a category you really want. Nor should you worry if you do rather badly in any particular test. The tests cover a wide range, and for that reason it is to be expected that you will do well on some and poorly on others ; indeed, they are designed to disclose what are your [italics] special [/italics] strengths and weaknesses. Also no one test counts for very much by itself ; if you do badly in a test, you will find that you get another chance in some other test later on.

If you feel you want to, there is no harm in questioning others who have taken the tests before ; but you are not likely to learn very much of value, because there are so many tests that you will probably find the answers more confusing than helpful. Remember what the tests are for – to give the Service a measure of your present skill and aptitude. You can do nothing now to make either appear better than they really are ; the only mistake you can make is to have them appear lower. So regard it as your job to do the best you can with each test as you come to it, and remember that after the results are assessed your personal preferences will be given full consideration.

Before you start the tests, be sure that you are physically well. If you feel unfit, it is your responsibility to tell your Flight

[page break]

6

Commander so. If necessary he can then have your tests and classification postponed until you are fit again ; but under no circumstances can you take the tests a second time.

And then?

After the tests you will continue your general service training, and during the last week at the A.C.R.C. your Flight Commander will tell you the air-crew category in which you have been placed. [italics] That [/italics] is going to be your position in the air-crew team. It is the best position for you, because it is the one for which you are most needed by the Service and to which you are best suited. It is also a category that you have chosen yourself from among the categories for which Service requirements plus the results of your tests have made you eligible.

On finishing the A.C.R.C. course you will either go to a Grading School and then on to an Initial Training Wing (I.T.W.) or you will go straight to an I.T.W. At the I.T.W. you will begin specialized training with other men of the same air-crew category.

There is approximately a fifty per cent. chance that after A.C.R.C. you will go to a Grading School. Some half of the cadets leaving A.C.R.C. at any given time have proved by their tests that they would be likely to do well in pilot-training. If you are one of these and have also stated the pilot category as your first choice, you will be given the chance of going to a Grading School. Here you will go through the initial stages of learning to fly. This process is called the Flight Test, and because the few hours of standard flying instruction is affords permit your subsequent performance to be predicted with a high degree of accuracy, the R.A.F. uses it to determine finally who shall be classified for full pilot-training.

So going to a Grading School does not [italics] necessarily [/italics] mean that you are going to be a pilot. It simply means that you have shown enough promise to justify the Service in now giving you an expensive but very effective aptitude test, so that it may be able to judge, from actual performance in the air, who are most eligible for pilot training within the quota allowed.

Before leaving A.C.R.C. for a Grading School, you are told what your alternative air-crew category will be if you do not secure a pilot classification. In going to grading, you must understand that you are being given a full chance to show the degree of natural aptitude you have to learn to fly, and that you are quite

[page break]

7

prepared to serve in the alternative category if it turns out that you are less apt as a pilot than others. Finally, remember that not to qualify for pilot-training does not mean that you have failed ; it means that you showed promise and justified the use of a test which could not be given at A.C.R.C.

After I.T.W.?

If you qualify at the I.T.W. for the category that has been chosen for you, at the end of the course you will be given 7 days' leave, with pay and a free travel-warrant to your leave address. After leave, your next movements are as follows :

AIR BOMBERS, NAVIGATORS, PILOTS }

A few who are to be trained in the United Kingdom are posted to units here. The great majority go to an Air-Crew Despatch Centre (A.C.D.C.) to await posting overseas to continue their training.

WIRELESS OPERATORS (AIR) }

To a Technical Training School in the United Kingdom for a specialized Signals Course. Subsequent training is then done either in the United Kingdom or overseas.

FLIGHT ENGINEERS }

To a Technical Training School in the United Kingdom.

AIR GUNNERS }

To Air Gunnery Schools in the United Kingdom.

Fuller details about these later training stages are given at the end of this pamphlet. Do not hesitate to ask your Flight Commander if you want to know still more about them.

Delays

In conclusion, just a few words about delays that may occur between successive stages of your training.

Everything humanly possible is done to prevent delays, but if you find that you have to wait between training courses, remember that in a war of this gigantic size and scope it is not always possible to keep training running neatly and smoothly to a standard blueprint schedule. If there were no enemy, this might be possible ; but there is an enemy, and this means that a training organizatoin (sic) belonging to a fighting machine must be able to change to meet

[page break]

8

new situations as they arise. For example, intakes and training courses are planned to match the likely strategy and tactics of the United Nations and the enemy in some eighteen months' time. Then shipping movements, production difficulties, changes in operational requirements and a score of other factors may well alter the plans ; and as one of the direct results you may find yourself waiting at a Despatch or Reception Centre, impatient to go on to the next stage of training.

If you are held up, make the best of it. Your understanding and co-operation are worth ten times all the grumbling. Learn what you can while waiting. Take part with enthusiasm in all the recreation that comes your way ; and keep cheerful – it will help a great deal to keep the other fellows cheerful too.

[page break]

9

AIR-CREW DUTIES AND TRAINING

EARLIER IN THIS PAMPHLET you were promised that the last section would tell you something about the duties and training of the six basic air-crew categories. This is it. First, there is a brief description of the duties of each category, in alphabetical order ; possibly you will find that none of the jobs is as simple as you may have thought. Then there is a plan of the whole system of training ; all categories come together at A.C.R.C. and nearly all will come together again before training is complete. But in the meantime you will be sent many different ways ; if you are interested in what is likely to happen in each case, the diagram will help you. And at the end there is a brief explanation of the nature and purpose of each of the schools and courses that is shown in it.

When reading this section, remember that the training phases, course-names and the like are those in force now. This means that in some cases you may reach a training stage in several months' time to find that arrangements differ from those described here. Some of the reasons for changes occurring in the training plan have been given on pages 7 and 8.

[Air Bomber brevet]

THE AIR BOMBER has such varied duties that his is one of the most interesting jobs in a squadron. As his name implies, his main responsibility is the actual bombing of the target ; the navigator brings the aircraft to the target area, then the air bomber takes over to direct the pilot over the target, identify the aiming point and bomb it. But he has other work to do during the rest of the trip ; throughout the whole flight he acts as the eyes of the navigator, map reading whenever possible and taking astro-sights, noting the weather and sometimes operation special wireless

[page break]

10

equipment. He is an essential member of the navigation team and all his reports are entered in the navigator's log or on the plotting chart. The air bomber is also trained to man a gun position so that, in emergency, he can also help to defend the aircraft. Lastly, he may have to help the pilot by taking spells at flying the aircraft straight and level on a course, if no flight engineer is carried on that particular type. Thus the air bomber needs special knowledge and skill in many subjects : the characteristics of bombs, and ammunition, the theory and practice of bomb-sighting and aiming, and of air gunnery, the principles of DR navigation, rules of thumb for taking auto-sights, map reading, aircraft recognition, pyrotechnics, reconnaissance, signals and photography. His training is a long one, but it is full of varied interests.

[Air Gunner brevet]

An efficient AIR GUNNER must have four main attributes. First, a gift for rapid and accurate brain-hand-eye co-ordination ; for in a matter of seconds he must be able to recognize an enemy aircraft, estimate its range by knowing its span and comparing it with the size of his ring-sight, judge the position of the enemy in relation to his own aircraft, apply the simple rules of aiming, manoeuvre his turret to bring the guns to bear, and fire to hit the enemy. Second, he must be really fit, and have marked determination and fighting spirit. Third, he must be able to keep calm and talk clearly to the captain when his aircraft is in action. Fourth, he requires some mechanical aptitude for reasoning out, under difficult conditions, the causes of gun and turret faults and for rectifying them quickly. The task of the bomber aircraft in which he is most likely to serve is to hit its target with bombs. During flight, the air gunner is the eyes and the sting of the aircraft. His watchfulness must give the pilot warning of approaching enemy aircraft, he tells the pilot what tactics to adopt to evade action ; and if combat does develop, his skill in destroying or driving off the enemy determines the outcome of the sortie.

[page break][missing pages]

15

[italics] ITW Initial training wing. [/italics] Different ITWs for each category. General service training combined with an introduction to subjects important in each category's future training.

[italics] OTU Operational training unit. [/italics] Run and staffed by the operational commands ; here categories are crewed up, made familiar with an operational type and prepared in every way for their operational role and eventually posted as crews to operational squadrons except in the case of heavy bomber OTUs, which are followed by HCU.

[italics] PRC Personnel reception centre. [/italics] Air crew received from overseas training, help pending posting to AFUs etc.

[italics] PRE-OTU [/italics] A short course for navigators (W) and wireless operators (air) before posting to Coastal Command OTUs. Comparable in function to AFU.

[italics] RADIO SCHOOL [/italics] Basic training in signals for wireless operators (air) and navigators (W). First half of course mainly theoretical, second half includes ample flying experience. WOps (air) qualify here for badge.

[italics] RADIO COURSE [/italics] A course for straight navigators who have volunteered and been selected for special training after which they are qualified as navigators (radio) and posted to Beaufighter and Mosquito night-fighter and intruder squadrons.

[italics] SFTS Service flying training school. [/italics] Basic principles of flying for war purposes taught on advanced trainers, combined with full syllabuses of ground subjects. Pilots qualify here for flying badge.

[italics] SofGR School of general reconnaissance. [/italics] Pilots and navigators for Coastal Command receive full training in the additional navigational and tactical subjects necessary for Coastal work.

[italics] TTS Technical training school. [/italics] Full technical training for FEs, who qualify here for FE badge.

[page break]

16

[system of training diagram]

492 Wt.59682-T2932 20,000 4/44 Gp.8 F. & C. Ltd.

[page break]

Prepared and Issued by

THE AIR MINISTRY

A M T

This pamphlet is RESTRICTED ; it is not to be shown to anyone outside the service, nor to be taken into the air

[page break]

[bird logo]

F.2915 Wt.59682 20,000 4/44 Gp.961 Fosh & Cross Ltd.

Collection

Citation

Great Britain. Air Ministry, “Your Place in the Air Crew Team,” IBCC Digital Archive, accessed July 27, 2024, https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/collections/document/28838.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.