Interview with Ernie Patterson. One

Title

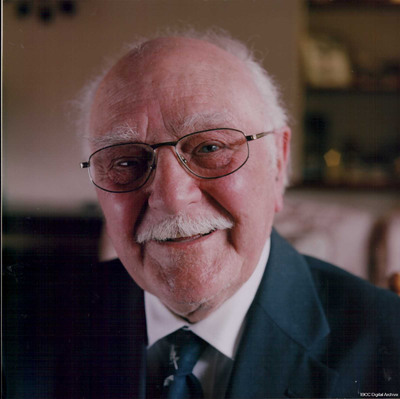

Interview with Ernie Patterson. One

Description

Ernie Patterson DFM was born in Middleton St George in Darlington. At the age of 14, he left school and took on a job as an apprentice Joiner.

He joined the Royal Air Force at the age of 19 in 1941, but whilst he was waiting to be called up, he was helping to build a bomber station and what is now Teesside Airport, also completing work at the satellite station of Croft.

Ernie trained as a Wireless Operator, where he did well with Morse Code. He did his training in February 1942. He was sent to Evanton in Scotland, where he also trained as an Air Gunner.

He flew Proctors, Whitleys, Dominies, Avro Ansons, Halifaxes, Lancasters, Liberators and had a trip in at Catalina Flying Board. Ernie flew with 635 Squadron, which was part of the Pathfinders Force.

Ernie completed 51 Operations, flying to Stettin, Chemnitz and Hanover. He was part of the Master Bomber Crew to Dorsten, Kiel, Nuremburg, Osnabruck and Heligoland.

After the war, he was in charge of flying control in India, handling the closing of a Flying Boat base and arranging for them to be returned to the UK.

Ernie left the Royal Air Force in 1946 and returned to work as a Joiner, retiring from work at the age of 78.

He joined the Royal Air Force at the age of 19 in 1941, but whilst he was waiting to be called up, he was helping to build a bomber station and what is now Teesside Airport, also completing work at the satellite station of Croft.

Ernie trained as a Wireless Operator, where he did well with Morse Code. He did his training in February 1942. He was sent to Evanton in Scotland, where he also trained as an Air Gunner.

He flew Proctors, Whitleys, Dominies, Avro Ansons, Halifaxes, Lancasters, Liberators and had a trip in at Catalina Flying Board. Ernie flew with 635 Squadron, which was part of the Pathfinders Force.

Ernie completed 51 Operations, flying to Stettin, Chemnitz and Hanover. He was part of the Master Bomber Crew to Dorsten, Kiel, Nuremburg, Osnabruck and Heligoland.

After the war, he was in charge of flying control in India, handling the closing of a Flying Boat base and arranging for them to be returned to the UK.

Ernie left the Royal Air Force in 1946 and returned to work as a Joiner, retiring from work at the age of 78.

Creator

Date

2015-10-08

Language

Type

Format

01:14:01 audio recording

Publisher

Rights

This content is available under a CC BY-NC 4.0 International license (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0). It has been published ‘as is’ and may contain inaccuracies or culturally inappropriate references that do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Lincoln or the International Bomber Command Centre. For more information, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ and https://ibccdigitalarchive.lincoln.ac.uk/omeka/legal.

Contributor

Identifier

APattersonGE151008, PPattersonGE1501, PPattersonGE1502

Transcription

AM: Hang on then.

EP: Can’t we just chat before you start doing that?

AM: Ok Right. Well, we can, we can, but let me just say. Just, ‘cause they need this for the recording in a minute, that my name’s Annie Moody, and I’m here on behalf of the International —

EP: Anne who?

AM: Moody.

EP: Is that what you’re —

AM: No. He’s called Gary Rushbrooke.

EP: That’s right.

GR: She wouldn’t take my name.

AM: I wouldn’t, I’d never change my name, Ernie. And I’m doing the interview for the International Bomber Command Centre, and I’m, today I’m at the house of Ernie Patterson in Darlington, and it is the 8th —

GR: Yeah.

AM: Of October 2015, and you can talk now Ernie, and what I want you to tell me, first of all, is where you were born and what your parents did, and what your background was.

[pause]

AM: See you’re not talking now, come on [laughs].

EP: I was trying to tell you I was born at —

AM: Right. Middleton St George. Tell me about that.

EP: [unclear] Road, Number 19.

AM: Right.

EP: My mum was living with her sister at the time, and she had a baby boy a month after I was born, and we were both christened at the St Lawrence’s Church which is down by Middleton One Row. Right.

AM: Right.

EP: Because — he’s died by the way, two or three years ago. That was where I was born.

AM: Right. And you were telling me that that was right near Middleton St George.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Yeah. Which is now Teesside Airport, but which was a big bomber base.

EP: That was part of my working career. I helped to build which is, which was Middleton St George bomber station, and I also worked and helped to build which is now Newcastle Airport.

AM: Right.

EP: When the RAF took it over.

AM: So, you were born there. Did you have brothers and sisters?

EP: Eh?

AM: Did you have brothers and sisters?

EP: Yeah. I was one of six.

AM: Right.

EP: There’s three of us left.

AM: What did, what did your parents do?

EP: My dad was in the Boer War.

AM: Yeah.

EP: He, not the Boer War, rub that out. He was in the Battle of the Somme.

AM: First World War.

EP: And he was badly, he got badly shot up there.

AM: Right.

EP: ‘Cause I’ve been — can I jump? I left school when I was fourteen. I’ll go from there, eh?

AM: Yeah. Ok.

EP: I left school when I was fourteen, and I decided to serve my time as an apprentice joiner at fourteen, and my pay was twenty seven P a week. True that.

AM: Five and four pence.

EP: Five and ten pence.

AM: Five and ten pence.

EP: In old money.

AM: Yeah.

EP: That was then, and I was, and I was in to the deep end straightaway by putting rooves on with improvers, they were called, and when you got to twenty one in my day, you got the sack, ‘cause they had to double your pay.

AM: Right.

EP: You had to go and work for somebody else. In my working career, I’ve been a joiner all my time, which is why — and I’ve got no City and Guilds, Higher National. Nothing.

AM: So that’s what you did.

EP: Experience. I just seen it happen and I just took it all in. Mind before I built this, I built a few garages for people and that give me the incentive and this — I took it on myself. And I was working twelve hours a day some days to get. It hardly rained.

AM: Yeah. So, at fourteen —

EP: Yeah.

AM: You started off as a joiner.

EP: Apprentice joiner. Yeah.

AM: Yeah.

EP: I was getting — the pay was twenty seven, you know, for forty four hours that.

AM: Blimey.

EP: That’s what it was. Twenty seven P.

AM: Did you enjoy it, Ernie?

EP: I enjoyed every work of my time of my working career.

AM: Right.

EP: And I was never out of work. I left school when I was fourteen and I worked until I was seventy eight, and I had a week off on the sick in all that time. Apart from giving the RAF four years.

AM: Four years. So why the RAF? What made you go for the RAF?

EP: I liked Brylcreem, didn’t I [laughs].

AM: What do you mean you liked Brylcreem?

EP: Well, we used to be the Brylcreem boys, weren’t we?

AM: True

EP: I used to use it, so I had to join the RAF, didn’t I?

AM: There must have been more.

EP: But what annoyed me was, I didn’t get the Defence medal because I was non-operational, such as being in the Home Guard or the Fire Service or anything. Yet I helped to build two big bomber stations. That should have counted, shouldn’t it?

AM: Right.

EP: So, you can check on that for me and get it for me. The Defence medal.

AM: Right.

EP: I was in touch with Gloucester, well you know what I mean, and this is what he came on the phone with. He said, ‘You only had two years’. Well, that was the two years when I was training in the air, how to be aircrew.

AM: Right. So, wheeling back a bit. So, when you, so you joined because you wanted to a Brylcreem boy. I’m not sure I believe that was the whole reason, but it’ll do.

EP: I had black wavy hair. I couldn’t. In the Army, you do a lot of marching don’t you? And in the Navy, I’d be seasick.

AM: Right. So, you decided to join the RAF.

EP: So, I joined the RAF. I was whipped in to the cream.

AM: You were whipped in to the cream. Where did you, where did you did you —

EP: I was deferred for a while. I was nineteen when I was called up.

AM: Right. So, what happened between eighteen and nineteen then, because I thought, weren’t —

EP: I was working in 1941, building bomber stations. Middleton St George and the satellite at Croft.

AM: Right. Tell me what you mean then. You were working there.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Working for whom?

EP: Helped to build, helped to build, working on [pause] such as Teesside there. Twelve flat rooves, you know, pitched rooves.

AM: Right.

EP: It was all shuttering, you know. We had to build —

AM: When you say you were working as a joiner? You hadn’t joined the RAF

EP: I’ve been a joiner all my life.

AM: Right. Got you.

EP: I built this place but I had no experience of brick laying. Just I’d seen them doing it.

AM: Just built it

EP: Built it.

AM: So, so from, so you started off as a joiner at fourteen.

EP: Yeah.

AM: And at eighteen you were working on the airport.

EP: 1941. When the war started in 1939 — I can take you to the pair of bungalows. I was seventeen at the time.

AM: Right.

EP: And I did all the joinery work on this bungalow for a builder who, he was working as a boss on another building firm, but he built these pair of bungalows in Darlington. Woodcrest Road. And I did everything on that, I was only seventeen then. Then when the war — that was in 1939, the day the war started. I can see it as if it was yesterday. They stopped building. You couldn’t get, you couldn’t get material to do building. They needed it for war work, didn’t they?

AM: So, what did you, so what did you do at that point?

EP: I got with a firm that was doing [pause] which is — not Middleton St George. Croft. It was a satellite of Middleton St George. I started work there as a joiner.

AM: As a joiner.

EP: It was a satellite of Middleton St George.

AM: Right.

EP: And then from there, I went to, when I got moved from there, for the same firm to Newcastle. I was lodging in Lady Park Road and it was about five shilling a week bed and breakfast at the time. Five shilling a week.

AM: All still as a joiner.

EP: I’ve never been, done anything else

AM: So, when you actually joined up with the RAF then, how old were you at that point?

EP: That was in September 1942.

AM: Right.

EP: I was nineteen, wasn’t I?

AM: You were nineteen.

EP: Work it out. Yeah.

AM: And where did you go to join up?

EP: I just got called up, didn’t I? I had to go.

AM: Right. Ah, so you got called up.

EP: You had to be registered. I had to go.

AM: But for the RAF.

EP: No, I volunteered for that.

AM: Right. So, you got —

EP: Flying was. Aircrew was voluntary.

AM: So, you got called up but you volunteered for the RAF.

EP: That’s it.

AM: Right. Ok. Got you. So, having volunteered for the RAF what happened then? What was the sequence of events?

EP: It was in the February of 1942. I can always remember. I was, I had to go to Edinburgh on an aircrew selection board.

AM: Right.

EP: And it was there they decided to make me a wireless operator. Because they do you tests and they could see that I could, they send you Morse code, and they’d send you a note or something, and they’d send you something else, and you had to say if they were both the same. That’s how they were testing you. But they found I could take Morse code in.

AM: Right.

EP: And they made me a wireless operator.

AM: Right. So where did you go?

EP: It was on my mum’s birthday. 4th of February 1942.

AM: Right.

EP: And I was accepted into the RAF then but it wasn’t until the September that I was called up, and by then, I was eighteen, nineteen or something.

AM: Right. So, so when you were called up, when did you start doing the training for the wireless operator? Where did you do that?

EP: When I was called up in the September.

AM: Right.

EP: ‘42.

AM: Still — yeah.

EP: Blackpool, wasn’t it?

AM: Was it? Blackpool.

EP: You learned the Morse code in the Winter Gardens. And they were all civilian ex-GPO bloody operators. It was Morse code then, wasn’t it? Telegrams and all that.

AM: So, what was it like then? Going, going to Blackpool.

EP: There was RAF all over. Everywhere, every, every boarding house had RAF in. You could see them at parading and that. And Woolworths, I think it was Woolworths or Marks and Spencer where they kept all your documents. We used to have to do guard duty on, on, I remember they used to say you had to learn something if you were challenged at night by the orderly officers and that, but you were protecting government property. And Burton’s was an aircraft recognition place. All these places were taken over by the RAF.

AM: Yeah.

EP: We used to do PT on the sands and we used to — where else did we go? We got [unclear], known as a pressure chamber, that happened there, but we did a route march to somewhere. Shooting ranges. You did everything in Blackpool. Then from there, I was posted to a place called Madley. This was the RAF now, Madley. I was trained to be a ground wireless op. We learned Morse code as a ground wireless operator. Then from there, I went to Yatesbury and I was trained to be an air wireless operator. Then from there, I was sent up to Evanton, up in Scotland and made an air gunner, which I was never in the turret. That was a waste of time because I was never in the turret. I was a wireless operator all the time.

AM: So, you — but your training was wireless operator, and then you were trained air gunner as well.

EP: I was a wireless operator air gunner.

AM: What was the training like at Yatesbury?

EP: Well, you flew in Proctors. Single aircraft with just a pilot and you, and you got, you got your, you had your transmitter, receiver in front of you. You had to push it back to get in, then pull it over like that., and you were experiencing air sickness and all that weren’t you? Then from Yatesbury, we get — do you want me to keep going?

AM: Yeah.

EP: Then from Yatesbury, we went to Abingdon.

AM: Yeah. You’re all over the country, criss crossing the country.

EP: Not Yatesbury. After Evanton, up in Scotland, I was a fully-fledged sergeant there. I got my brevet and then from there, I was sent to a place called Milham. Have you heard of Milham? It was an Advanced Navigator’s Flying Unit, and we flew with scrubbed navigators and wireless operators in Ansons. And from there, we were all sent to Abingdon but we all — pilots, all the —

AM: Right. So —

EP: In this big hangar.

AM: So, Abingdon is the Operational Training Unit where you crewed up.

EP: Where we crewed up.

AM: Tell me about crewing up.

EP: Well, they never said, ‘You’re flying with him’, and, ‘You’re flying with him’, you picked your own crew in there didn’t you?

AM: So how did it happen for you then? Who picked who?

EP: Well, someone just comes. I don’t know who picked me, but this I always remember, he was Jack Harold. He was a pilot and he was about a couple of years older than me at the time. What would he be? He’d be about twenty two and I was twenty, and it was just a matter of you just got together. I can’t remember how it happened, but from there, we flew down as a crew to this satellite of Abingdon, which was called Stanton Harcourt.

AM: So, who, who were the crew at that point? How many of you?

EP: There was seven of us then

AM: Were there a full seven of you?

EP: Seven of us.

AM: Right. Ok.

EP: Do you want me to give you the names?

AM: Yeah. Go on.

EP: Well, there was the pilot, that was Jack Harold which — he’s dead now. Jack Garland, the navigator. Lofty Thompson was the second navigator. Ernie Patterson, me, was the wireless operator. Snowdon was the mid-upper gunner and George Sindall was the rear gunner. And Alan Purdy was the flight engineer.

AM: Right.

EP: How about that from memory.

AM: Well done.

EP: And we trained at Acaster Malbis.

AM: Yeah.

EP: And it was there where Lady Luck was on our side for the very first time. We were sat waiting for this Whitley to come back. Is that? I think, let’s get this right first, but we were fired on the first time, we’d been flying in the daytime in this Whitley, and for some reason, we were flying in the same aircraft on the night cross-country run, and we had this crop who had an instructor pilot and an instructor wireless operator and for some reason, they changed the aircraft. The instructors wanted to fly, you know, we changed aircraft for some reason. They crashed and they were all killed. That was the first time when Lady Luck was on our side. And the second time, the second time we had that Lady — the second time, we were waiting for this Halifax to come back at Stanton Harcourt. It was doing two engine overshoots and that, and they crashed and they were all killed. Lady Luck was on our — and we were waiting for that aircraft. We were sat outside waiting for it to come back so that we could take it over, but it had engine trouble and they crashed.

AM: And this is all while you were all just doing your training.

EP: That was while we were doing — there was about nine thousand killed training.

AM: Yeah.

EP: But let me think. So, when we went on to a squadron, the pilot, you see after, we ended up at Rufforth flying Halifaxes from Whitleys. But this was Whitleys at Stanton Harcourt. But we ended up — but the next one was Rufforth near York, in the York area, and when we graduated, we’ had about forty hours on Halifaxes. We had the chance to go on to Main Force, which was 10 Group which was Melbourne or 635 Squadron, see. So, we plumped for the Pathfinder squadron.

AM: Right.

EP: And we went there for the Path. We were there a month before we did any, any op, and training all the time. And all this time we had this aircraft we were given for pre-flight training in and went to do a DI on it. Daily Inspection.

AM: Ok.

EP: And across, I did a crow flies. I walked towards the plate to it and I found this horseshoe. Threw it over me shoulder like that. I thought I’ll keep that.

AM: And you’ve still got it.

EP: It flew with me. All the flying I did from there.

AM: What was the extra training you had to do as Pathfinders then?

EP: Well, in the first place you had to do two tours. Main Force, you did one tour which was —

AM: Yeah.

EP: Well, we went on this squadron. The pilot flew with an experienced crew to give him, as second dickey, to give him extra to see what it was like before he took his own crew.

AM: Ok.

EP: So consequently, he did thirty trips. We all did twenty nine.

AM: You did twenty nine.

EP: And the pilot and the two navigators — they were posted overnight. We didn’t even get to say cheerio. But I’ve seen the pilot a couple of times since the war.

AM: So, when you got there to 635 Squadron.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Pathfinders. Can you remember your very first operation?

EP: Oh aye.

AM: Go on. Tell me about it.

EP: It was in August. We went to Stettin. You’ve heard of that haven’t you? In Poland.

AM: Yeah.

EP: And we went up. It was an eight and a half hour trip.

AM: For your very first operation.

EP: Yeah, and we lost twenty three bombers that night, I’ll always remember that. But you see with the pilot going around another crew to get experience, he done thirty trips. We had done twenty nine. But when you’re just, you’re supporting the markers.

AM: Yes.

EP: You’ve got markers on the Squadron. Certain ones. But when your brand new, you’re supporting the markers. Well, this is why, after he’d did thirty trips, him and the two navigators, well we never got off supporting those. We were supporting the markers all the time.

AM: On right.

EP: So, I got on with another crew. They’d lost their wireless operator. He was, he crashed, they crashed. That’s another story. They were on two engines coming back to this country and he ended up on one engine and heading for Woodbridge. Crash landed, and the wireless operator was killed and he’d done about eighteen trips and I’d done about the same. And I got him, I got his job.

AM: So, after about eighteen operations, you swapped over on to a different crew.

EP: Yeah.

AM: And who was that? —

EP: No. I’d done twenty nine.

AM: Oh, you’d done - right Okay

EP: I’d done twenty you see. That was a tour you see.

AM: Yeah.

EP: They liked you do two tours because you’ve got all the latest equipment.

AM: Yeah.

EP: And you’re using the equipment that the main force doesn’t have.

AM: Tell me what it was actually like Ernie. Going up and doing that. An operation.

EP: Well, you used to get the battle order going up in the mess, didn’t you? As soon as you saw your name on the bloody battle order, you couldn’t get in the toilet. You had all the toilets there, wash basins there, but you’re going to be coming and then when we come out of the toilets. The fear.

AM: Everybody?

EP: People say, ‘Were you were frightened?’ But constipation wasn’t a problem in those days.

AM: Were you frightened?

EP: Of course, you were. You were shit scared.

AM: Right.

EP: That was it. You wanted to go, that frightened feeling, you wanted to go to the toilet but you were waiting. All the toilets were occupied when the battle order went up.

AM: Right. And then what?

EP: Well, it —

AM: Describe it to me. What it was — you know, from actually getting the battle order right through, doing the operation, and coming back.

EP: Well once you knew where you were going to, you stayed over at the bomber. They didn’t let you out, and you’d maybe be over an hour, an hour and a half waiting to take off. Much of the time you did that, they’d come out, it was cancelled, and everybody went back to their billets, got changed and out for the night. You lived for the day.

AM: Why would they cancel it?

EP: Don’t know. Maybe a lot of cloud. Something.

AM: Yeah.

EP: But I survived. You know how many ops I did, don’t you?

AM: I do.

EP: How many?

AM: Well, he’s told me. Fifty.

EP: One.

AM: Fifty one.

EP: Yeah. We kept going until we all had done the fifty.

AM: But I want to know what it felt like, what it was actually like going. So, on the ones that weren’t cancelled. That’s it. You get in the plane. And then what? [pause], I know [laughs], I know you’re laughing at me but —

EP: Well, you settled down. You got daft you know; it’ll never happen to me. It’s not the [unclear]. As soon as you knew you were going, you thought, ‘Dear me, is this it?’ You know, and you couldn’t, you couldn’t get in the toilets for the [unclear].

AM: Right. Once you’re on the plane though, you set off. In — other people who have talked to us have talked about the bomber stream, but you were the Pathfinders so —

EP: Well, the elite of the Bomber Command was the Path. Now to be Master Bomber which we did five.

AM: Yeah.

EP: You’re the elite of the elite. When I got in to the second crew.

AM: Right. I’ve —

EP: And the first time — they used to mark the target. Mosquitos. There were a lot of Mosquito squadrons and they’d be the first to drop the white flares. The aiming point somewhere there. Now, you had to have a good bomb aimer and he’d pick it out like that. He’d be the first there, and I can always remember, and our call sign was Portland One and we had a deputy with us, and he was Portland Two, and main force was called Press On.

AM: Right.

EP: That was the call and he’s had to set thing up and tell the skipper, he could talk to them, and we would be approaching the target he starts. The Pathfinders. The flares would go down. Some would be on the target, some would be off, then you’d get another colour going out. Green maybe. And you’d tell them to ignore the greens, that’s off the target, and bomb the reds that’s fading away. They were still over the target area.

AM: When they dropped the flares? So, they dropped the coloured flares to mark the position.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Did they drop bombs as well?

EP: Yeah.

AM: Or did you just do flares.

EP: You make the bomb up. Yeah.

AM: You had a full bomb load as well.

EP: You carried it all, yeah, and I can always remember, sticks to my mind, full tanks. If you went on a long trip was two thousand one hundred and fifty four gallon. That, that’s full tanks which sacrificed bomb load for fuel.

AM: Yeah.

EP: If you were going on a long trip. For the Stettin raid, seven and a half hour trip, and we flew over Sweden, didn’t we? As we were flying over Sweden, they opened fire because it was a neutral country wasn’t it. Wasn’t it?

AM: Yeah.

EP: You remember that. Neutral country. And they fired up, and this pilot was listening out and he said, this person said, ‘You are’, he listened to them and they said, ‘You are flying over neutral territory’. And this pilot answered him, ‘We know’. Coming back over the same route, they opened fire again, and this pilot spoke to them and said, ‘You are three thousand feet off target’. And they says, ‘We know’. You get that.

AM: Yeah.

EP: True story that. They would open fire, they weren’t trying to hit you, they were just warning shots. ‘You are flying over neutral territory’. The pilot said, ‘We know’. Then coming back so they opened fire again, he said, ‘You are three thousand feet off target’, and they said, ‘We know’ [laughs]. They weren’t trying to hit you, just warning shots. That was that. And we lost twenty three bombers that night, I’ll always remember that. Some of them come down in the North Sea or something. But the most, the biggest raid I was on, was Hanover, when we lost thirty one bombers that night. And on Chemnitz, we lost thirty five bombers on the two raids we went to Chemnitz. But I did a Master Bomber raid on Dorsten, Kiel, Nuremberg, Osnabruck and Heligoland. How about that from memory?

AM: Wonderful.

EP: And we did two deputy Master Bombers.

AM: So, tell me what, tell me what the Master Bomber does.

EP: You go around and around on operations.

AM: You’re the first one though.

EP: Yeah. You go around, and you can contact your deputy. He’s there, he’s there with you and you’re going around and around all the time. And you see red flares went down and the, no, they might not be on the aiming points, because our bombers identified the aiming point. The target could have been in front or behind the flares or to the left, and you’d tell the skipper to speak to all the bombers. To main force. To bomb in front of the reds, or to port.

AM: And it’s the bomb aimer who drops the flares.

EP: Yeah.

AM: And it’s the bomb aimer who says whether it’s —

EP: Yeah.

AM: Hit the target or —

EP: So, then the next flares would go down. It may be green because it would confuse them and they might be way off, and you’d tell them to ignore them. The Master Bomber would speak to all the bombers and say ignore the greens, bomb the feeding reds, or the instructions he’d given for the flaming reds.

AM: And it’s the Master Bomber who’s saying that.

EP: Yeah. Yeah.

AM: Not you as the wireless operator.

EP: No.

AM: I imagined it would be you as the wireless op.

EP: I had to write everything down he says, because I’m the only one who can write it down.

AM: Ok.

EP: But I’m writing everything he says down. And when I got back, Intelligence took my log book off me. They could tell how that raid went off by reading my logbook.

AM: Right.

EP: This is what I have to get to, after the raid was over, my skipper would assess the raid, whether it was successful or not. He’d tell me, and I’d be in touch with, I’d be in touch with our headquarters which was at Huntingdon. In Morse code it was 8LY, I’ll always remember that. And I put them in the picture about whether it was a success or not in bomber code. Nothing — you didn’t use plain language; it was all in code.

AM: Right.

EP: And bomber code altered you read at 6 o’clock at night. At 6 o’clock the next morning was different. The same thing meant something else, because you had to have all your information on sugar paper. Just for a bit of extra. We used to tear it off and chew it, just to make sure. It was sugar paper.

AM: Sugar paper. I’ve never heard of sugar paper.

EP: Yeah. All the information had to be destroyed, you know, if you crashed you had to eat that.

AM: Oh, you had to eat that. Literally. You’re not pulling my leg.

EP: Yeah. That was, it was sugar paper, you had to eat it.

AM: Right.

EP: And when I first went on the squadron, they gave me a bloody 38 revolver. We had a revolver each. I thought, what are you going to shoot. Who are you going to shoot with that? They’ll fire back at you, won’t they? I had, I had to draw it out. You had to go on the range and fire the bleeding thing. In those days, you fired like that. You used to go up. Nowadays it’s like this isn’t it? Two, have you noticed?

AM: So, its two handed now instead of one handed.

EP: It’s two hands now. In those days you fired like that. Two hands now.

AM: So where was the revolver in the, in the —

EP: Well, I should put mine down me flying boot.

AM: Down your flying boot.

EP: And the ammunition down that one. If you bailed out, then they’d drop out wouldn’t it [laughs].

AM: Can we go back?

EP: That used to be my biggest fear, seeing the bloody places burning. To think I’ve had to bale out into that lot.

AM: You never did though, did you?

EP: It used to frighten the bloody life out of me.

AM: Were you ever [pause] right. Right. Wheel back a minute. When you changed crews. So, at what point was it that you changed crews, and who was the new crew?

EP: That’s him there. That’s Alex Thorne.

AM: Alex. So, Alex Thorne was your pilot.

EP: He was, he was thirty three year old then.

AM: Which was old.

EP: And he’d a lot of experience.

AM: At the time.

EP: Thirty three year old and experienced, wasn’t he?

AM: Yeah.

EP: He was an instructor at one time.

AM: And who else was on the crew with you, Ernie?

EP: Sorry.

AM: Who else was on the crew with you?

EP: Well in that, I can always remember. There was Alex Thorne. Harry Parker, the navigator, the wireless — the flight engineer. Boris was the nav, so the second navigator.

AM: Boris Bressloff.

EP: Graham James — Graham Rose was the navigator. Scott was the mid-upper gunner. Jimmy Rayment was the rear gunner. How’s that? And Joe Clack was the bomb aimer.

AM: Right.

EP: I think we had two or three. I think we had three. But we were experienced crew. As I said, to a be a Master Bomber in the Pathfinders, you were the elite of the elite.

AM: And that was when you became — did the Master Bomber. So how many times, you said you were the Master Bomber five or six, I’ve forgotten.

EP: We did five. Last couple as deputy Master Bomber.

AM: And two deputies.

EP: Towards the end of our, to the end of second tour, if our squadron wasn’t supplying the Master Bomber, we were the only crew stepped down. Different squadrons would supply a Master Bomber for different raids and towards the end there — it’s in the, I’ve got my logbook there.

AM: I’ll have a look at your logbook in a minute if I may.

EP: It’s good reading in there. There’s a couple of raids we were on. Master Bomber there.

AM: Ernie’s showing me pictures here of the —

EP: Take offs. I took ten take offs in Dominies, thirteen in Proctors, fifteen and thirty five in Ansons, forty eight in Whitleys, sixteen in Halifaxes, a hundred and five in Lancasters, three in Liberators, one in Catalina, and twenty two in bloody all other aircraft.

AM: In a Catalina? What were you doing in a Catalina?

EP: I went to India when I finished flying. You’d got —

AM: I’ll come back to that after.

EP: That’s a long time.

AM: Yeah, I’ll come back to that story after. The two pictures are pictures of, describe, just describe those to me. What are they actually pictures of?

EP: Well, that’s — that’s Heligoland.

AM: Right. Yeah.

EP: You’ve heard of that? And on there, you see, there’s a fighter base, the garrison and the U-boat pens.

AM: And who would have taken that picture? The bomb aimer?

EP: No, the aircraft.

AM: The aircraft. The air. Oh, it’s an automatic camera, isn’t it? Yeah.

EP: And that one’s Oldenburg. It tells you that and that was Alex the day I was, they are the target indicator. Did you know that the target indicators cascaded a thousand feet? Did you know that?

AM: No.

EP: There’s a fuse on the end. I can always remember. They were eight pound a piece then. What happened? The flares don’t go up? You see them cascading, don’t you? Well, the pressure at a thousand feet ignites them.

AM: And that’s the flare.

EP: That’s the flare. But the full, full amount of five hundred pound bombs and you’ve got the four thousand pounder, to be carrying the four thousand pound bomb all the time. And you know, they’re distributed off the aircraft you know. They don’t just all go off. It’s distributed so that it keeps the aircraft level.

AM: Yeah. So, you don’t —

EP: So, it doesn’t go top heavy. They distributed off the bombs so the aircraft —

AM: How many would one aircraft drop? How many flares would you drop?

EP: Well six or seven.

AM: Yeah.

EP: Of different colours. But —

AM: So, you’d do your first colour first.

EP: Whatever — you see. You’d make it —

AM: And you’d drop them all together, but you’d know which one had —

EP: Everything’s dropped in a big —

AM: Right. Ok. So, tell me —

EP: You’ve got the full five hundred pound going down together, but they all balanced off to keep the aircraft level, you know. They don’t all go ruddy together. Should keep the nose down.

AM: ‘Cause I’m imagining that you dropped —

EP: You see, at night time, there’s a photo, you’ve got a photoflash and you’ve got a photoflare in the chute. Half way down the aircraft. It’s a quarter of a million candle power. That’s what you measure light with isn’t it? Did you know that?

AM: No.

EP: That’s candle power. And it was a quarter of a million candle power did this flash. Now, when you drop your bombs at night, your camera takes over and takes up the release point in case you’re not in the position, ‘cause you’ve got to be straight and level to get the photograph at night you know.

AM: You’re supposed to be still and level aren’t you, as it’s taking it?

EP: It works out so when your bombs hit the deck and flares, the bombs hit the deck and the flares are going down behind them. The photoflash flashes and your camera takes, all synchronised together so your bombs hit the deck, your flashes and your camera take over. Take a picture. All three together. Nobody operates it. You relied on [unclear], that was one of the things. Marvellous.

AM: Yeah.

EP: But I used to have to be sent back to put my hand down the chute to make sure the bugger had gone. What would have happened if we’d landed and it had stuck? And it stuck on its way down. What would have happened if we’d gone with —? That operated at a thousand feet as well.

AM: So, what did you do if it hadn’t gone?

EP: You had to make sure that it had gone. There was ways of ejecting it.

AM: Right.

EP: What would have happened if you’d got down to a thousand feet?

AM: Oh yeah, I can imagine.

EP: It would have exploded and that would have been the aircraft.

AM: I can imagine.

EP: It would have been on fire.

AM: I can imagine. Yeah. I just had, I just had this picture of you crawling back along the aircraft to make sure it’s gone.

EP: Yeah.

AM: And it’s still there.

EP: Yeah, if it was, you would have had to make sure. There was ways of releasing some the bombs and that.

AM: Why would you have released it.

EP: You can take the plates off. If you’ve got bombs hanging off. Sometimes you’d maybe land with the bombs stuck up, but you make sure they’ve gone. You can always tell. When you lose the bombs, the aircraft goes up like that, you know. When you lose bombs in the air, in day light was the worst. You could see the bloody aircraft go over and over and the bomb doors open, and some of the shear bombs shooting past you, just goes past your wing tips. They knocked turrets off as well, didn’t they? You can’t see them. It was a hell of a thing. Aye. Daylight was the worst. Everyone jockeying to get near the target and the bomb doors were open, and they’re going over to get into position. He drops his bombs and he goes up like that. You’ve dropped yours at the same time and you’re going to be back alongside him again. But that’s what it was like.

AM: If you were at the front. So, you’re the Pathfinder at the front and there’s all the other aircraft behind you, did they come up alongside you then.

EP: You see, you’ve got to be, you had to work to time. Time was essential. You had to be in that position in the air at that very — so you didn’t bump into one another. That was worse? You were colliding with one another. You had to be in that right spot all the time. Otherwise for every, if you go, for every hour in the air to a target, you’ve got five minutes to play with. Now, if you found that you were right, you had to pick a spot where you’re going to lose time. If you were five minutes earlier than where you should be. So, you could either make a big orbit in the bomber stream, which wasn’t very nice, or you could alter course sixty degrees to port. Fly out of the bomber stream for five minutes. A hundred and forty degrees. You fly back in in five minutes. Everything was — and you got back on course and you’ve only gone that bit and that’s where you lost a bit of time.

AM: Who made that decision?

EP: Well, it’s [unclear], it’s all, that’s what you’ve got to do as a navigator.

AM: It was the navigator.

EP: He told us. And we had H2S on there you know, which had an eighteen mile radius. He used to check with the pilot. He used to just tip the aircraft like that, to keep the nose, to keep them on course. You could be on course and off track you know. You could be there, on course, but off track in relation to the ground. See what I mean?

AM: No.

EP: You can be on course and on track.

AM: Right.

EP: That means you’re in the right position on the ground, in relation to the ground.

AM: So, what, what’s HS2? Is that the — ?

EP: That’s the big blister. I forget what it’s called but that — it had an eighteen miles —

GR: Radar.

AM: A radar.

EP: Radius. If you were going past some built up area and you knew what was there. They knew all this. You just had to just, skipper to the tip the aeroplane and it flickered, so it sent the rays out there. It picked the building up and gave you some idea. He was wonderful. You wouldn’t think he was on operations. Our navigator, Graham Rose. He was that all the time. Very vigilant. And he was plotting our position every six minutes. A little diamond on his route. Wonderful navigator. Wonderful pilot. Wonderful. I think this is why we survived. We were in the right place at the right time. I was asked that when they interviewed me at the Teesside airport, when the Canadian Lanc was there — how come I survived like that. I said, ‘I think we were in the right place at the right time’, and I’ve seen bloody aircraft blow up in the sky.

AM: Eric, Eric said didn’t he, another chap that we know, said that they kept safe all due to the navigator.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Who kept them in the middle of the bombing stream all the time.

EP: He was the main man, not the ruddy pilot in my eyes. The navigator was the main one in the bloody Lanc. Definitely. He wasn’t, I’d ask him to have a look, have a look at it. I’d step down. Have a look now. Your pals can’t see bloody much, there’s fog and there’s wingtips. They can’t see bloody much on the ground. It’s everybody else can.

AM: Did you ever get shot at? Well obviously, you got shot at. Did you ever get hit?

EP: Just with flak.

AM: Yeah.

EP: I remember I seemed to suffer more with that with the first crew I was with. We used to get out with all the paraphernalia and walk around the bomb site when we knew we could count. Flak mad.

AM: What? While you were still up there?

EP: No. When we landed.

AM: When you landed.

EP: You could walk around and see how many holes in it. And you could whip through ruddy wires that were all clipped together like that, whip through them like butter if you got hit by flak. You see, in my compartment, I had what they called Fishpond and you could see any aircraft underneath you, ‘cause you had it up. It could fly underneath you and shoot you down. We had no protection at all underneath, they used to fly and fire upwards into you. That’s how he shot. There was a show on recently. A bloody German fighter pilot, that’s what he used to do. Shoot them down like that. Shot many a Lancaster down. He was showing them in his logbook where he shot you down, even took the letters of the aircraft that he shot down, this German pilot. If you could see them, well you see with this Fishpond, it took the centre of the H2S and if an aircraft, a fighter were going underneath you or anything you would see them. It would blip.

AM: Did your gunners ever manage to shoot anybody down?

EP: Well, if they don’t fire at you, you don’t fire back at them, you just bloody ignore them. But what do you do if you get a fighter on your tail, there was a recognised corkscrew. Did you know that? If they’ve got a fighter in front of you know, to hit you, like, when you know you see the American things. They’re coming up the side but I don’t know how they do it, because you’d be all flying that way. He’s coming this way. See what I mean? Well —

AM: Because of the speed of the aircraft. And the guns.

EP: The German fighter’s going to fire came in front of you ‘cause you’re all going that way.

AM: Yeah. So, you fly into it.

EP: So, if he’s coming at you and you’ve got the back. If you come this way, you’ll hear the rear gunner telling him to corkscrew to starboard. Go like that with a Lanc. Take it down like. The German fighters got to come around like that. He breaks away and he comes down and he, and you come around and you come back up like that. And you can see the bloody propeller just fanning around with the force of gravity all the petrol away from the bloody, from the propellers. From the engine. You can just flip them around. You come go on to there and get back on course. Come at this again. They don’t fire at you. You just keep out of the way.

AM: You just keep out of the way.

EP: Don’t blow your — that you’ve seen them but night time, everything’s is black. You can’t see anything. And coming back fifty miles from base, this is another tip, I had to call up base to get the barometric pressure of the base so that the pilot could put it on his altimeter. Of course, there were no lights on. You’ve got to get other side before you can see the runway lights. And we had FIDO then. Do you know what that was?

AM: I know what FIDO was. Did you ever have to land at a FIDO airport?

EP: Yeah. One or two. I can always remember though the very first trip I did with this new crew, we went to, it think, was it? It was Chemnitz, I think, but we got, I got a call from Group headquarters. We had to go and land at Ford of all places. Yet we had FIDO on account of training command — a lot of them had landed there, but when you get a group broadcast, you’ve got to do what they say. We could have got down and landed at FIDO but I got a message, and we had to go and land at Ford, down near Southampton it was. I can always remember that, and we were stepped up to ten thousand feet. There was that many bombers needing to land there.

AM: What’s it like seeing that because it’s petrol burning, isn’t it? Along the runway.

EP: Aye. That’s all it is. It just disperses the fog. When you fly over, did I tell you, you drop like that when you’re coming in to land. There’s one coming this way, when you’re coming in to land and when you fly over, you can feel the aircraft drop down with the heat does it. But when we went to Ford there, course it’s a straight bloody bomber station. When we did eventually land, these women bloody controllers they were the ones. They used to make their voices very clear. They knew what they were doing. I used to — a women operators at flying control. They brought them all. They’d speak to every bomber ’cause they made touch with you there. Some were calling up on three engines, wanting to get down. Giving them priority, and they’d talk to everyone. Bring them all down like that, speak to every one of them. Then when we landed, where did we go, a little van used to pull up in front of it and big words, “Come on. Follow me”. This little — and you followed this little van and you followed, and he switched his lights off, and you knew that was where you’ve got to stop. The next day, you had to go and find your bomber.

AM: I was just going to say.

EP: There was that bloody many there.

AM: So, you’ve all landed. You’re there. What? And you’re at “foreign”, in inverted commas, airport.

EP: Yeah

AM: And that’s — where did you sleep? Just where ever you can.

EP: Pick your own. That was ok, you just picked your billet. There was empty billets.

AM: Oh right. Ok.

EP: You slept in all your flying gear, and maybe there was a meal for you as well, which you got every time you went on ops. You got proper eggs bacon and chips every time you went on ops. And when you came back, you got it. They were all rationed in Civvy Street. Yeah.

GR: Ford was the emergency landing base.

AM: Yeah.

GR: On the south coast.

AM: Yes.

EP: And the next day, they went to find our bomber and we get, I think, I don’t know whether we got fuelled up or something, but we were hedge hopping all the way back.

AM: What does that mean?

EP: Very low. We called it.

AM: Right.

EP: When you’re very low, you call it hedge hopping. I was that low. It took us about an hour to get back, it took us about an hour to get back because I had to phone up base. Call up base to let them know we were on our way. Did you know bomber aircraft wasn’t allowed to go in the air without a wireless operator?

AM: I didn’t.

EP: Navigator? Yes. I can remember when I was flying in the Whitleys. It’s in that book. The numerous air tests I did, with just me and the pilot. Used to always call for me from the sergeant’s mess. I could find, if he got lost on an air test, I could get him back to base. He didn’t have to have — that was why no aircraft was allowed off the ground without a wireless operator.

AM: Because you’re the connection.

EP: Well, you can call me.

AM: Back to —

EP: You can call it.

AM: Yeah.

EP: The navigator wants to make sure I can get a fix for him from in the air, as a wireless operator you know. There’s three stations in the country, you call that one up and these two are listening to him working you, so then you go through the procedures. He takes a bearings on you.

AM: Yeah.

EP: He takes a bearing on you, and he takes a bearing on you, and he plots them all on his charts and where they all cross — that’s your position.

AM: And tells you where you are.

EP: Five minutes after, you can ask him again if there’s nobody else bloody working them. And you turn them all together, you could see where you are in the sky. You needed a wireless operator all the time.

AM: Yeah.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Gary was telling me a story as we were coming up, about a day when you were ready to take off and your fuel gauges was showing nil.

EP: Oh, that was when the skipper got a DSO for that. We were the Master Bomber that day.

AM: So, what happened? Tell me. What was the story?

EP: We’d been training in the day time right. And the Army couldn’t take Osnabruck. Whoever was trying to take the opposition. So, when you’re doing training, cross country, if you’re not on ops, you’re doing cross country training and bombing in The Wash. And I’ve got to contact base every half hour and I got the [unclear] for me to return to base. So, we came back to base. We were briefed straight away and we were taken out to the bomber and we took off straightaway. That’s how urgent it was. Otherwise, you’re waiting for an hour, an hour and a half before you go, and we took off before we should. In the end, we got in and found we hadn’t enough petrol. Skipper said to Harry, ‘Can you work out how much we’ve got?’ So, he said, ‘We haven’t got enough to get us there and back’.

AM: So that was when it was Alex Thorne.

EP: That was Alex Thorne.

AM: Yeah.

EP: So, he said, ‘We’ll go and we’ll bale out over France’, so, we were taxiing out to take off, got to the end of the runway and he pulled in to one of the dispersals. Broke RT silence and then we had to get the fella — the bowser driver had gone to the NAAFI for his break and they had to get him back. And so, we got the navigator, we cut that leg off and dogleg to the target. Cut that leg out and go to that one. Time was going by. Cut that leg out and go straight to the target. We took off on the wrong runway and flew straight to the target. And we got, and that was the day the highest we ever got, we got up to twenty three thousand feet. I’ll always remember that. And I can remember as we were approaching the target, skipper was weaving to get predicted with the radar. And there was about six bursts of flak on our tail. Straightaway, the rear gunner said, ‘Dive skipper, dive’, and we were up at twenty three thousand feet that day and he put it in to a dive, and you can imagine them reloading and firing and I was in the astrodome looking out. You could see all the bursts following us down as we were going down. You could see all the bursts. You know that, you know the feeling when you’re the last one to go to bed. You go up the stairs, thinking some buggers behind you and that, when you’re a kid, and that’s the feeling I got. When you could, you wanted to go faster. And you ruddy, you could follow this flak burst. That split second earlier, they would have hit us. And of course, the skipper, we started, and all the bombers were approaching the target and we were coming this way, and the skipper got in touch with the deputy, and that’s how the raid went on. And the skipper got the DSO for carrying that raid. We were the Master Bomber that day. We had to go. Now, if we didn’t, it would have happened? No Master Bomber. The raid would have been a flop. But we couldn’t. They couldn’t. They would have promulgated. He got the DSO on that raid. It was on Nuremberg. Another raid. We did a Master Bomber raid on Nuremberg, and we were on the approach. We were approaching the target, we got, I think we were just going to drop our bombs, and we got a wall up and the aircraft went into a dive, and Harry said — he had his back up against the pilot, pushing the stick back for the skipper, and it didn’t respond, and all the bombs gone. It eventually responded on its own, but by the time he had he got it around, it had gone in to the [unclear], because the deputy took over and took them further into Germany. As if Nuremberg wasn’t being far enough. But this [unclear], we were all on our, weren’t we? They’d all gone, the raid was over. There’s these two fighters coming towards us, I could see the gunners were waiting for them. They were two Mustangs. Better aircraft than the bloody Spitfire by all means. And do you know what? One of them came right alongside us. He had his hood back and he was a coloured pilot, American, and he was smoking a big Havana cigar. To let the smoke out. What do you think of that? And the other one was on the other side, and they escorted us back a hell of a way and as soon as they left us, in no time, a Spitfire came alongside and escorted us back.

AM: And escorted you back. Was the one in the Mustang — were they the Tuskegee’s were they called?

EP: I don’t know, but it was a coloured pilot.

AM: Yeah.

EP: And he had the hood back to let the smoke out.

AM: With his cigar.

EP: Smoking a Havana cigar.

AM: Waggling his wings at you.

EP: True story that.

AM: Yeah.

EP: We were escorted back a couple of time, with a Lancaster once, then it got shot down. Jack Harrold. I think it was on the Ruhr. We got, we’d gone three engines and this bloody Lanc flew up alongside. I’ve got a letter from what the skipper wrote to him, I’ve got the letter somewhere, but he found out after he got killed. He got shot down that lad, and in his letter, he said, ‘Do unto others as they would do unto you’. He said, if I’d left you, because when you lose an engine, you know, you lose all bloody sorts, you know, ‘cause all your power and that to your guns and dropping your wheels and hydraulics, and all the power comes from your engine.

AM: So, it’s not just the engine. It’s everything that it was powering.

EP: So, if an engine bloody stops, you know, the ways you could lose if you. I don’t know which engine it was but if you lost power with that you can’t — your wings. You’ve got to drop your wings, crank them around to get to lock them. Now where I sat in my place, I could see, I could see the wheels. I used to tell. When the skipper selected me, when we were coming in to land anyway, you could see the wheels had dropped down and I could feel the power build up then. You could see them do that, and I used to tell them they’d done that. I let him know that at least they had locked. If you’ve got, if you hadn’t got the indication on your panel on the aircraft. It’s a wonderful bloody aeroplane, the Lancaster, wonderful aeroplane.

AM: Wonderful.

EP: I’ve got three hundred and fifty hours flying one, and I think about two hundred and seventy operational ones, and we used to, when we were going on ops or were going on bloody training, we used to do cross-country’s for the navigators. We’d meet up with a bloody Spitfire or a Mustang for the gunners to have, you know, for the fight, and in The Wash, there was a triangle in The Wash. Did you know that? We used to drop ten pound smoke bombs. You could see them. Just ten pound in weight. They were little tiny bombs for the bomb aimer and this used to fascinate me. When we, this was on the way back, that was part of the training, and when you, the pilot would make contact with the base [unclear], whatever, and we were going to drop these bombs, and you had to tell them what height you were at. Do you know what they used to use for the height? Angels. Now isn’t that nice? We’re at Angels 10. Ten thousand feet. Now, isn’t that lovely?

AM: Yeah.

EP: That was a difference of not saying ten thousand feet. Angels 10.

AM: Ten. Angels 10.

EP: Wasn’t that lovely? That’s what they used to tell us what height we were at, ‘cause you just had to keep flying low, turn around and keep coming back and drop a one or two. That was —

AM: So, was there continual training in between the operations then?

EP: Oh aye. You would turn up when you were on ops. Every day was the same. Saturday. Sunday. There was no Saturday and Sunday. Any day. Aren’t you saying something?

AM: That was to Gary who is sat with us. Aren’t you? Have you got anything to say Gary? Any questions? Any extra questions?

EP: I think he’s put a bit of weight on as well, you know

GR: Oh, thanks Ernie.

EP: Haven’t you. Eh?

GR: I’ve lost weight.

AM: Never mind weight. Have you got any questions?

GR: When did you get your DFM?

EP: After we finished, didn’t we? I was recommended for a commission you know, after the war. I think, you know, how that worked if there was officers left. Officer’s mess if a crew get approachable, two of his crew. Now Jimmy Rayment, the rear gunner and me, after we’d, we’d finished flying, I think, I think it was after we bloody got out of the ruddy bomber at Heligoland. That was the last trip I did. And he said he’d recommended us both for a commission. Of course, we got a fortnight’s, leave, didn’t we? We all went on a fortnight’s and while I was on my fortnights, we decided to get married, didn’t we? So, I waited for another fortnight to get my —

AM: Oh, I was going to ask you when you met your wife and all that.

EP: Because what they do — you ask for a fortnight. They say seven days granted.

GR: Yeah.

EP: So, I’d asked for a fortnight, I only wanted seven days and I got the bloody, I got the fortnight and during that fortnight, the war ended. I was married on the 5th of May and the war ended on the 8th, didn’t it?

GR: Yeah.

AM: Yeah.

EP: Did you know that? I was on leave, weren’t I, and I got bloody posted to do another bombing, to another Pathfinder squadron. Off my leave. I thought, well what about my commission? They must have thought, well the war’s over now. We were surplus, or they’ve, ‘cause Jimmy, he went back, didn’t he? And he got his commission but I didn’t. I ended up in bloody India. I had to do something. I ended up in charge of flying control in India.

AM: I was going to ask you what —

EP: And this why, this is why I got the trip in the Catalina. Out there.

AM: So —

EP: I was then put in charge of bloody flying control out there. And I was dealing with flying bods coming from Hong Kong to the UK for demob.

AM: So, hang on. So, the war finished, then you got married.

EP: I got married on the 8th

AM: And then before demob —

EP: I got married on the 5th of May.

AM: Yeah.

EP: 1945.

AM: Yeah.

EP: The war ended on the 8th of May.

AM: Yeah. So then when did you get — so the war’s ended but obviously, it’s a long while before your demob.

EP: That was always first in were first out, but I did get, I was offered my class B release.

AM: What does that mean?

EP: Because I was a builder, wasn’t I? Joiner.

GR: Yeah.

EP: Yeah.

EP: They wanted you in Civvy Street then. Right. I was going to jump the queue and come out before I should do.

AM: So how did you end up in India then?

EP: The thing was if you, if you took your Class B, you go where they’re sending you and you got a fortnight’s leave. Well, I didn’t want that, I wanted to pick my own bloody job, so, I waited for my Class A release which was about five or six weeks after my release would have been up. I got, I took the month’s leave I was entitled to and I went and worked. Picked my own bloody job which was near home.

AM: Right. Tell me just —

EP: You had to go where they sent you when you did that.

AM: Just before you tell me about the job, tell me about going flying your Catalina and going to India.

EP: From Chelmsford I went, I think from there.

AM: Did you go on your own or were Harry or Boris or any of them with you?

EP: Lots of them were posted then until your demob number came up. It was always first in, first out, when your demob number come up.

GR: Was that just you Ernie? It wasn’t any of the other crew. It wasn’t Harry, or Boris or any of them.

EP: No. No. I think Harry — he went flying straightaway with Cheshire, didn’t he?

GR: Yes.

EP: Did you know that?

AM: Yes, I did. Yeah.

EP: Harry. Harry and Cheshire went up in to Scotland and bought two Mosquitos for seven hundred and fifty pound, and one of them only had twenty flying hours in. And Harry flew with Cheshire, setting up Cheshire homes in Europe.

AM: Yes, I remember that.

EP: Harry did that.

AM: So, where, where did, tell me again why you went then, before you were demobbed.

EP: I went to a place called Korangi Creek in India, near Karachi.

AM: And what were you doing?

EP: I was just — you had to do something until your demob number came. I ended up, I was in to accounts but I didn’t do it, go into it. I was in, it was a Flying Boat base which was in the process of closing down, and we were dealing with Sunderland Flying Boats coming from Hong Kong to UK for demob, and I used to have to deal with them. You see, once they left Hong Kong, they were my pigeon. Then when I left them — they left me, I had to organise petrol for them and all the meals and whatever. Fill them up. Then when I, then when they left me, Bahrain was the next stop. But it was, I used to wire Bahrain to let them know it was on its way. It was their pigeon. And it was there, and I used to, and these Sunderland Flying Boats used to take off the next day, and I used to arrange them for the meals for them and accommodation where I was, and I’d go with them to the launch with them, with the Anglo Indians, to see them off. And on this particular, we were in in this launch going along, and this Sunderland Flying Boat coming alongside me. Well, all of a sudden, for some reason, they turn off the bloody flarepath, like that, and this bloody fella driving the launch — he didn’t see him [laughs] and we were all bawling at him. There was a few of us on this launch with him, and I spoke to the pilot about it. He said, ‘I’m sorry’. I’ll always remember that. It was, and I think, do you know what? They approached me to join them. BOAC took it over. He said, ‘You’re a wireless operator. We need wireless operators. Why don’t you join us?’ I said, ‘Well I’m in the bloody RAF, aren’t I?’ When you get out you join us. We need wireless operators. I didn’t.

AM: Why didn’t you, why didn’t you?

EP: I wanted out. I’d already had enough of bloody flying, I wanted out, and they used to approach me. They had ones that would, they had their staff, we had ours. He said, ‘Why don’t you join us? We need radio officers in BOAC’. What might have — because I’d been pulled over the coals by the family for not taking it on. I wanted out, I’d done enough. Anyway, the thing was, I wasn’t up, when I was offered this commission. And the war ended. Whatever happened after that didn’t apply. But in a way — what they did with you, if you got a commission after you finished your flight, Transport Command they’d put you on. And I wanted out, I’d had enough of bloody flying.

AM: Yeah.

EP: But you never know. I’d been lucky up till then and that’s it. Only bloody birds and fools fly. But I wanted out and that was why I didn’t pursue it. I could have pursued it and they might have got me something earlier, and they posted me to another Pathfinder squadron, and I got posted from there. I ended up at Biggin Hill. I could always remember that. How [unclear] I was

AM: What were, what were you doing there?

EP: Just in transit all the bloody time ‘til they decided what to do with me. [Unclear] was there. I met up with him, he was at Biggin Hill.

GR: When did your demob finally come through?

EP: When?

GR: Yeah. When did you actually finish in the RAF?

EP: September ’46.

GR: ’46.

EP: See, another thing, if I accepted, if I’d accepted a commission — another way I looked at it. You get discharged out the RAF and brought back in as an officer, different number and that and you’ve got stay in at least twelve month from being a commission.

AM: Right.

EP: I thought I want out, I want out sharpish. I didn’t. it was another bloody twelve month before I didn’t come out. So that was it. I turned it down, I didn’t pursue it, but that was it. I ended up as a warrant officer which was automatic.

AM: Yeah.

EP: But my bonus out of the war was meeting to meet my beautiful wife. She was in the land army

AM: Where did you meet, where did you meet, Ernie.

EP: She was in the land army. She was in the land army in Wisbech.

AM: Right.

EP: I met her in the November. We were engaged and married in six month.

AM: So, she was in Wisbech. Where? Was that when you were based near there then?

EP: I was based at Downham Market.

AM: Oh, at Downham Market. Of course, you were. Yeah.

EP: I was based about fifteen miles away.

AM: Where did you meet her then?

EP: At a dance.

AM: At a dance.

EP: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

AM: What was she called, Ernie?

EP: Kathleen.

AM: Kathleen.

EP: Yeah. She was a lovely person.

AM: She was your bonus.

EP: I’d have died a thousand deaths to keep her. I could have packed. On Pathfinders, you know, you’ve got to do, they like to do two tours. Main force you do thirty.

AM: Yeah.

EP: Which is one tour, and you go away to be an instructor somewhere and they get you back to do another fifteen, but towards the end of the war, they weren’t doing that. They were just doing the thirty. Now, Americans only did twenty five, and then they went home, didn’t they? ‘Cause they all flew straight and level all the time, but we flew a different pattern altogether. Americans.

GR: Do you know how many ops Alex Thorne did in the end?

EP: He did about fifty three. Fifty four.

GR: Fifty three. Fifty four.

EP: Yeah, but I keep referring to this. When I read anything, I keep referring to this, it’s all in here.

AM: Ernie’s got his logbook.

EP: I’ll just show you some. An operational page [long pause] In red, it’s night time. Green, it’s day time.

AM: Yeah.

EP: And it’s, here in the, the number of ops I lost. On the fifty odd raids that I was on, we lost two hundred and seventy five bombers. But it’s the number of ops and the number of aircraft lost on that raid. So, it’s all, it’s a very interesting book this. Look at all. Look at that page for a kick off. In that. See all the —

AM: Yeah. I’m looking now at, I’m looking now at the different raids so Chennai, Dessau

EP: Chemnitz. See, all the times I was in the air is in the next column.

AM: Eight hours. Yeah.

EP: And the number of ops and the number of aircraft we lost. If you go the other way, that’s there’s some more. Some more. It’s quite a — one of my proud possessions that. Did you know, did you know when you’re selected as a Pathfinder, you’ve got to be marking and you get a certificate. You can be pulled up by the RAF police in the town. You could have a permit to wear those little gold wings. Did you know that?

AM: No.

EP: You’d have a permit and when you finished flying you got a permanent certificate from Bennett. I’ll show you.

AM: I’m looking, I’m looking at this one here. So, the operation — Heligoland.

EP: That was the last one.

AM: As Master Bomber, and then you’ve written in blue underneath, abortive sortie. So, there was a final abortive sortie after the Heligoland.

EP: That was, that was another one. I don’t know whether — I think if you can get within a certain distance, you can count it as one.

AM: It was like a quarter of an operation

EP: So, I did. So that’s it. it could have been fifty two. On the countdown. But go back to where you see more ops.

AM: Oh yeah. There’s —

EP: See.

AM: Yeah.

EP: Do you see all those amongst the people you interview?

AM: Yeah. Lots of people have got logbooks. Some haven’t but some do.

EP: Have you seen them all?

AM: Hmmn.

EP: How many had the DFM then?

AM: Sorry?

EP: How many had the DFM?

GR: Not many.

AM: I can’t. Not many.

EP: Do you know there were twenty thousand DFCs given out? Eight hundred and seventy DSOs. Six and a half thousand DFMs. This is why the DFM is more.

AM: Is more. It’s more.

EP: Did you watch that Antiques Roadshow the other night? Monday night.

AM: No.

EP: There was a lad on there. He’d had his grandad’s DFC, his medals, I have, and his logbook like that, and do you know how much they valued it at? Between three and four thousand pounds.

AM: Blimey.

EP: Now, I’ve got the Pathfinder certificate.

AM: The Pathfinder. Yeah. I’ve found the, I’ve found that one where you were Ford to base.

[Recording paused]

GR: Not with my interviews but when I’ve visited —

AM: So, I’m looking here at Ernie’s award of his Pathfinder Force badge, which certifies that, “1567159. Flight Sergeant Patterson, GE. Having qualified for the award of the Pathfinder Force badge and having now completed satisfactorily the requisite conditions of operational duty in the Pathfinder Force, is hereby awarded permanently his Pathfinder Force badge, issued on the 22nd of April 1945”. Signed by —

GR: Bennett.

AM: Bennett. Who was the air officer commanding of the Pathfinder force. And Ernie’s going to show me his badge in a minute, I think. What’s he fetching me now? I’ll try and get some scans of some of this information.

EP: This is, this is a permit to wear it before you get that.

AM: So, what Ernie’s telling me is that you have —

EP: You could be pulled up by the police.

AM: Come and sit. Come and sit down again and tell me about this

GR: Do as she says [laughs]

AM: So, the permit says, and it’s issued from the headquarters of the Pathfinder Force, again, to Flight Sergeant Patterson. “You have today qualified for the award of the Pathfinder Force badge, and are entitled to wear the badge as long as you remain in Pathfinder Force”, and again, signed by Bennett, Air Vice Marshall. So, what did the badge mean? Tell me. Tell me again. What?

EP: You can see them.

GR: It’s there.

AM: Yeah, but you were telling me. Yeah, I’ve got it. And you were telling me that if you were pulled up by the police

EP: RAF police. They used to have red hats on and —

AM: Yeah.

EP: In the town. Because people used to masquerade as wearing them, in the town, and wear it.

AM: Why. Why did they wear it?

EP: Swaggering.

AM: Oh, to swagger around in it.

EP: Showing off. That’s how they were. Another one.

AM: And I’ve got the letter from Buckingham Palace, “With the award that you have so well earned, I send it to you with my congratulations and my best wishes for your future happiness”.

EP: That’s what, that’s what appeared in the paper.

AM: And I’ve got a clipping in here from April 1945. A Darlington joiner gets the DFM.

EP: That was, that’s in the, I think that was taken on the —

AM: Blimey and I’ve got a picture here of Ernie with a wireless.

EP: That was 1154.

AM: I’m going to scan some of this stuff, but before we finish, I’ve switched it back on because I want you to tell me. I don’t — I don’t think it’s anything to do with the RAF, but you know your, your interest Ernie, in knowing all the different —

EP: I’m making sure my memory is still there

AM: Right. Hang on. Collective nouns.

EP: Yeah. What do you want to know?

AM: I want, I want to know loads of them. I want you to come and tell me some.

EP: You’ve seen the DFM haven’t you?

AM: But first of all, I’m getting to look at Ernie’s DFM.

EP: Have you seen some who have them?

AM: No, let me. I haven’t seen, I’ve not seen your one

EP: Of course they don’t

AM: Let me have a look.

EP: There’s the Pathfinder wing.

GR: That’s the Pathfinder wings which you wore

EP: There’s a Pathfinder wing.

AM: And there’s your DFM. So, the Pathfinder wing is actually a really beautiful — is it —

GR: RAF wing.

AM: Is it on a tie pin?

EP: Yes. It’s alright.

AM: And it’s the RAF eagle looking out towards the left. With the beautiful gold wings and the DFM, of course, is the one with the diagonal striped ribbon as opposed to the DFC one.

GR: And is the only medal with the recipient’s name on the edge.

AM: And is the only medal with the recipient’s name on the edge. Which I didn’t know. So, tell me some of these collective nouns.

EP: What time are you going?

AM: Tell me some, tell me some interesting ones.

EP: I’ve got dinner coming at 12 but I’ll put it –

AM: Why did you become interested in knowing what all the collective nouns are for groups of animals?

EP: I just read them. Some of them fascinated. Like a lot ravens. Unkindness. Isn’t that nice?

AM: A kindness.

EP: Unkindness.

AM: Unkindness sorry. Of ravens.

EP: Ravens. A lot of ladybirds. A love of ladybirds. Isn’t that nice?

AM: Lovely.

EP: Flamingos. A flurry of flamingos. A bale of turtles. A posse of turkeys. How many do you want to know?

AM: All of them.

EP: What they call a lot of moles. A movement. And that’s a nice name, isn’t it?

AM: A movement of moles.

EP: A movement, Moles yeah. And a lot of sparrows. A quarrel.

AM: A quarrel.

EP: You know what a lot of owls are. A parliament. A parliament of owls. It doesn’t sound right does it? Another nice one. A lot of snipe. Have you ever heard of a snipe?

AM: Yeah.

EP: A whisper.

AM: A whisper of snipes.

EP: Of snipe. Yeah, I looked them up.

AM: The wings just whispering. I could —

EP: And a covoy of pheasants. A covoy.

AM: A covoy.

EP: C.O.V.O.Y.

AM: I know that one.

EP: A covoy of pheasants.

AM: Yeah.

EP: No. Partridges that. A covoy of partridge. And a bouquet. A bouquet of pheasants. A town of giraffes. A crash of rhino. A pod of hippos. There’s lots of them. A destruction of wild cats. There’s a deceit of lapwing. An exaltation of skylarks. An ostentation of eagles. A mustering of storks. A flight of swallows.

AM: Just a flight of swallows.

EP: A flight. A flight of swallows. There’s lots of them. And what else? A sloth of bears. A sloth. A skulk of foxes.

AM: Some of them you can really see why and some of them you just can’t.

EP: Some are nice. And you get, what is it? A pace of donkeys, a barren of mules. You know why it’s called a barren?

AM: No.

EP: They don’t breed do they? They’re barren.

AM: Oh, a barren. Barren.

EP: Barren of mules. A mule is a cross between a donkey and a horse, isn’t it? They don’t breed mules. Did you know that?

AM: No. I did know that. But when you said barren, I was thinking baron.

EP: She can’t have kids, can she? I thought that was a good name for them. Mules. And you’ve got a charm of goldfinches. And a chime of Wrens. An army of frogs. A bevvy of otters. Do you know where otters live? Do you know what it’s called? Where otters live? A holt. H O L T. A holt. An army of frogs. A nest of snakes.

AM: What about toads?

EP: I don’t know about that one.

AM: No.

EP: But you get an array of hedgehogs. What do you call a lot of grasshoppers? It’s in the sky. What’s in the sky?

AM: Sun.

EP: Cloud.

AM: A cloud.

GR: A cloud.

AM: Oh cloud. of course.

GR: A cloud of grasshoppers. Yeah.

EP: I can remember the, what the great granddaughter — we met up with her when she was with her mum and dad one day and she had a pen and paper with her and I gave her fifty names.

AM: Brilliant.

EP: Yeah. That’s some of them. Some of them are a fascinating. Some of them — like a lot ravens. An unkindness. That’s my favourite. Nice, isn’t it?

GR: What was crows?

EP: Crows, a murder wasn’t it?

GR: A murder of crows.

AM: A murder of crows.

EP: That’s terrible that is. A mutation of, a murmuration of starlings and a mutation of thrushes.

AM: Is there one for swans?

EP: Eh?

AM: Swans.

EP: Swans. A bank.

AM: A bank of swans.

EP: That’s what it says. Some of them there’s three or four names for them but I just remember one of them.

GR: Yeah.

EP: A deceit of lapwing. An exultation of skylarks.

EP: Can’t we just chat before you start doing that?

AM: Ok Right. Well, we can, we can, but let me just say. Just, ‘cause they need this for the recording in a minute, that my name’s Annie Moody, and I’m here on behalf of the International —

EP: Anne who?

AM: Moody.

EP: Is that what you’re —

AM: No. He’s called Gary Rushbrooke.

EP: That’s right.

GR: She wouldn’t take my name.

AM: I wouldn’t, I’d never change my name, Ernie. And I’m doing the interview for the International Bomber Command Centre, and I’m, today I’m at the house of Ernie Patterson in Darlington, and it is the 8th —

GR: Yeah.

AM: Of October 2015, and you can talk now Ernie, and what I want you to tell me, first of all, is where you were born and what your parents did, and what your background was.

[pause]

AM: See you’re not talking now, come on [laughs].

EP: I was trying to tell you I was born at —

AM: Right. Middleton St George. Tell me about that.

EP: [unclear] Road, Number 19.

AM: Right.

EP: My mum was living with her sister at the time, and she had a baby boy a month after I was born, and we were both christened at the St Lawrence’s Church which is down by Middleton One Row. Right.

AM: Right.

EP: Because — he’s died by the way, two or three years ago. That was where I was born.

AM: Right. And you were telling me that that was right near Middleton St George.

EP: Yeah.

AM: Yeah. Which is now Teesside Airport, but which was a big bomber base.

EP: That was part of my working career. I helped to build which is, which was Middleton St George bomber station, and I also worked and helped to build which is now Newcastle Airport.

AM: Right.

EP: When the RAF took it over.

AM: So, you were born there. Did you have brothers and sisters?

EP: Eh?

AM: Did you have brothers and sisters?

EP: Yeah. I was one of six.

AM: Right.

EP: There’s three of us left.